Abstract

Purpose

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a psychological burden worldwide, especially for individuals with eating disorders (EDs). In addition, the healthy sisters of patients with EDs are known to present specific psychological vulnerabilities. This study evaluates differences between the general population, patients with EDs, and their healthy sisters.

Method

A group of 233 participants (91 patients with EDs, 57 of their healthy sisters and 85 community women) was enrolled in an online survey on general and specific psychopathology 1 year after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey examined associations between posttraumatic symptoms and depression, anxiety, obsessive–compulsiveness, interpersonal sensitivity, and eating-related concerns.

Results

Clinically relevant scores for posttraumatic disorders were found in patients with EDs. Healthy sisters scored similarly to patients for avoidance. Regression analysis showed specific associations between interpersonal sensitivity and posttraumatic symptomatology in patients and healthy sisters, but not in community women.

Conclusion

The psychological burden in patients with EDs is clinically relevant and linked to interpersonal sensitivity, obsessive–compulsiveness, and global symptom severity. Differences between patients, healthy sisters, and community women are discussed regarding vulnerability factors for EDs.

Level of evidence

Level III: evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case–control analytic studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The increased requests for mental health support and interventions linked to eating psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic have overwhelmed eating disorder (ED) treatment pathways [1], highlighting the needs for timely recognition and treatment [2] as well as evidencing personal and environmental elements that might play a role in psychopathology.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed people to traumatic situations due to the disruption of everyday routines, with an exacerbation of specific and general psychopathology [3]; this was defined by some authors as a social or collective trauma [4, 5]. Both patients and the general population reported escalations of eating symptomatology linked to COVID-19 restrictions [6] or exposure to traumatic and uncertain times [7, 8], showing difficulties in managing social isolation, depression, and confinement [9] and portraying symptomatology that is referable at a posttraumatic framework [5]. Longitudinal studies have shown the specific role of COVID-19 in regards to EDs, with patients reporting greater anxiety levels and increased concerns about the impact of the pandemic [10]. Fortunately, protective factors have also been identified, such as family relationships, social support, and therapeutic engagement [11]. Healthcare systems have been overwhelmed by the pandemic’s effects on staff members and the increased support required by patients, showing the psychological burden of the exacerbation of ED symptomatology caused by the loss of in-person support, the feeling of being undeserving of help, and the limitations of online treatment options [12]. Moreover, evaluation of the changes in the effectiveness of treatment before and during the COVID-19 pandemic indicates a reduction in the improvement in patients, calling for evaluations on the possible necessity of specific strategies and procedures to help them [13]. Overall, this evidence showed the possible role of environmental adversity in developing psychological distress, understood as isolation, low mood, anxiety, lack of structure, disruption to routines, and media/social media messages around weight and exercise [14, 15]. However, the data are still preliminary, and new insights are needed from population with specific ED vulnerabilities, to better understand the negative effects that have been recorded [16].

Personal history of maltreatment or traumatic events have been suggested as specific causes for the development and maintenance of EDs [17]. Furthermore, interactions between internal and external elements can modify patients’ physiological responses to subsequent stressful events [18, 19]. Even if no gender differences have been reported in the effects of traumatic events in EDs patients, the literature has shown that women and men have managed the events that have characterized the COVID-19 pandemic—such as confinements—differently due to the internalization of different psychological ideals [20]. The healthy sisters of patients with EDs shared their sisters’ difficulties in terms of emotional regulation, social threats, and executive functions [21, 22]; these elements could increase their hardships in dealing with the changes caused by the pandemic. Moreover, considering that ED patients and their relatives share psychological traits such as perfectionism, anxiety, and specific psychopathology [23], an evaluation of the differences between these particular populations could help determine the specific effects of shared traumatic events.

Despite the elevated psychological risk profiles of ED patients’ sisters, and the evidence of an increase of psychological distress in parents during the pandemic [16], to our knowledge, no study has considered this specific population in the evaluation of the effects of COVID-19; instead, they have focused solely on parents or caregivers [16, 24]. However, literature has shown that comparing ED patients and their sisters enable the evaluation of intra- and interpersonal moderating factors for the impacts of EDs [23]. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the presence of specific posttraumatic psychological differences due to the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample of patients with EDs, their healthy sisters, as well as a group of unrelated community women, searching for specific features that may explain the different negative effects of the pandemic in each subgroup. Our hypothesis is that specific posttraumatic differences and related psychological elements can be elicited between patients, their sisters, and community peers, contributes to the literature of the field and shows possible specific vulnerabilities that might be considered in future studies. These aspects may help the improvement of treatment approaches and the ED healthcare organizations, which have been overwhelmed by the worsening of patients’ symptoms during the pandemic.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was performed at the Vicenza Hospital ED Unit, composed of a day hospital and an outpatient service. The study design was approved by the local Ethical Committee and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. All the participants signed informed consent forms, and the survey was performed via Survey Monkey.

Sample

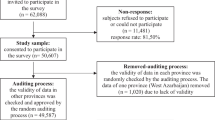

Participants were voluntarily enrolled through an online survey about their COVID-19 experiences. Three different samples—patients with ED, healthy sisters (HS) of enrolled patients, and community women (CW)—were recruited between January 2021 and June 2021, one year after the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The inclusion criteria for all participants were as follows: they identify as women; be between 14 and 40 years old, which is the usual range of ages of patients treated at the ED unit; and have no history of psychotic symptoms or severe medical conditions. Patients with EDs fulfilled the DSM-5 criteria for EDs as evaluated in person by a trained psychiatrist. The HS and CW were screened for the exclusion criteria of a personal history of any ED or psychiatric condition with specific items in the online survey; CW were also excluded if they had first-degree relatives with ED diagnoses. Patients were recruited via direct invitations; if present, their sisters were also contacted the same way, while CW were recruited via public announcements on social media.

Different strategies characterized the recruitment process. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, all patients treated at the day hospital or the outpatient services were directly enrolled for the study. If present, a trained researcher contacted the closest sister for each patient, screening the inclusion/exclusion criteria and obtaining the consent to participate. For the CW group, participants were enrolled via a public post on local Facebook pages about the search for volunteer participants for a study on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the population; the post was shared on different Facebook pages about community activities. All the participants were volunteers, and none knew the study’s aims.

Measures

The online questionnaire was composed of a sociodemographic section—including age, weight, height, years of education, personal and relatives’ exposure to COVID-19, and the current lockdown condition—and three different validated questionnaires in Italian: the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q), the brief symptom checklist (SCL-58), and the revised version of the Impact of Event Scale (IES-R). All participants were specifically instructed to focus on pandemic-related experiences when filling the survey.

For the healthy sisters and CW participants, specific questions were included in the survey to evaluate their psychological/psychiatric history, with a yes/no answer required: “Are you currently being treated for an eating disorder (e.g., anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa)?”; “Have you ever been treated for an eating disorder?”; “Are you currently being treated by a psychologist or psychiatrist for a specific your condition (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, etc.)?”; and “Have you ever been treated for a psychological problem (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, etc.) in the past?”.

The EDE-Q is a well-known validated 28-item self-report questionnaire specifically structured to evaluate eating symptomatology and attitudes [25, 26]. The measure contains four subscales, and higher total scores reflect greater eating-related pathology. Specific items allow the researcher to evaluate the frequency of particular clinical features—binge-eating episodes, self-induced vomiting, laxative and diuretics misuses, use of exercise as compensation—per month. In the current investigation, Cronbach’s α was 0.98 for the global score, 0.88 for the restraint subscale, 0.87 for the eating concern subscale, 0.94 for the shape concern subscale, 0.88 for the weight concern subscale.

The SCL-58 is a well-known self-report questionnaire derived from SCL-90R, and it is widely used to evaluate general psychiatric symptoms and psychological distress [27,28,29]. It provides a total score and five subscales: somatization, obsessive–compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, and anxiety. Each item is rated on a five-point scale, and higher total scores reflect greater symptomatology. In the current investigation, Cronbach’s α was 0.94 for the global severity index, 0.90 for the somatization subscale, 0.88 for the obsessive–compulsive subscale, 0.83 for the interpersonal sensitivity subscale, 0.88 for the depression subscale, and 0.85 for the anxiety subscale.

The IES-R is a 22-item self-report questionnaire that assesses subjective distress caused by specific events such as the COVID-19 pandemic [30, 31]. It is comprised of three different subscales (avoidance, intrusion, and hyperarousal) and a total score. Again, the participants were explicitly instructed to respond to the questionnaire in relation to their experiences of the pandemic. The clinical relevance cut-off for the impact of an event is 24. A score of 33 or above represents a possible diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder [32]. In the current investigation, Cronbach’s α was 0.97 for the total score, 0.81 for the avoidance subscale, 0.90 for the intrusion subscale, and 0.84 for the hyperarousal subscale.

Data analysis

Demographic information and specific and general psychopathology differences between the groups were evaluated using different analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. In addition, a Bonferroni approach was used in the post-hoc analysis. Lockdown conditions were classified according to the Italian legislation: yellow meant that people were not allowed to leave their homes from 10 pm to 5 am; orange meant that people were allowed to leave their towns only for work, basic needs, or health-related reasons; and red meant that people could not leave their towns except for health or work-related reasons. The distribution of lockdown conditions was evaluated using a Chi-square approach. Due to their equal distribution, comparison between underweight and normal weight patients were performed with a t test analysis. Instead, considering the different sample sizes, the patients were compared with the Mann–Whitney test to find differences linked to the various treatments at the evaluation. Furthermore, correlation between clinical features (binge-eating episodes, self-induced vomiting, laxative and diuretics misuses, EDE-Q subscales) and IES-R subscales were evaluated with Pearson’s correlation analysis. For the clinical features were used the specific items in the EDE-Q questionnaires. Hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses were applied to evaluate the associations between general psychopathology and EDE-Q global scores for posttraumatic symptoms linked to COVID-19. The IES-R total score was used as the dependent variable, while the SCL-58 subscales (Step 1) and the EDE-Q total score (Step 2) were used as independent variables. The effect size was evaluated with Cramer’s V for the chi-square and partial η2 for the ANOVA. All the analyses were performed using IBM-SPSS software vers. 25 with the alpha set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 254 women participated in the survey; of these, ten were excluded due to incomplete responses, and 11 were excluded from the HS or CW subgroups due to the presence of a personal or, for the CW subgroup, a first-degree relative’s history of ED. Therefore, the final sample included 233 participants: 91 ED patients, 57 HS, and 85 CW. The ED group consisted of: 48 females with anorexia nervosa, 24 with bulimia nervosa, eight with binge-eating disorder, and 11 with other specified eating disorders. The groups reported a significant difference only in regards to their average body mass index (BMI), which could be linked to the underweight of individuals with anorexia nervosa; ED group: 21.10 ± 6.49 years old, body mass index (BMI) of 19.50 ± 5.47 kg/m2, and 12.56 ± 2.77 years of education, all cisgender women; HS group: 21.52 ± 6.91 years old, BMI of 21.27 ± 3.70 kg/m2, and 12.77 ± 1.84 years of education, 55 cisgender women and two queer women; CW group: 21.98 ± 2.76 years old, BMI of 21.22 ± 2.39 kg/m2, and 13.34 ± 1.92 years of education, 79 cisgender women and 6 queer women. Due to the small sample of queer women, no subsample analysis were performed for genders for absence of statistical power. Regarding exposure to COVID-19, no differences were found across the groups in terms of personal infection (participants with previous infections included 9.30% of ED patients, 3.5% of HS and 10.6% of CW; χ2 = 3.82, p = 0.15), infection in cohabitant relatives (59.3% of ED patients, 60.8% of HS and 76.3% of CW; χ2 = 1.74, p = 0.36), or current lockdown situation (p = 0.31). The results of the psychopathological self-report evaluations are reported in Table 1. Differences were found between ED patients, HS, and CW, as the patients showed higher scores than the other groups in both general and specific psychopathology and their quantifications of the effects of the pandemic in their lives. See Table 1 for further details.

Using hierarchal multiple linear regression analyses, we evaluated the relationship between psychological features and the posttraumatic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. As reported in Table 2, we found different results for the groups: ED patients showed a significant regression model for IES-R Global Score with obsessive–compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, and global severity as predictors; in contrast, HS reported a significant regression model with interpersonal sensitivity and depression as predictor, and the CW group only reported a significant regression model for IES-R Total Score with depression.

Evaluation of clinical characteristics interactions

Examining the role of a condition of underweight in patients, no differences were found between the 48 underweight and 43 normal weight patients for general psychopathology or posttraumatic symptoms. The only difference that emerged was the mean scores of the restraint subscale of the EDE-Q questionnaire, which is linked to the different clinical presentation: underweight 3.39 ± 1.69, normal weight 2.63 ± 1.67, t (89) = 2.16, p = 0.03.

Correlation analyses between clinical features and posttraumatic symptomatology related to COVID-19 pandemic have reported specific significance relationships that are presented in Table 3.

Inpatients vs. outpatients

Patients recruited for the study were from both the day hospital (17 out of 91) and the outpatient services. When comparing these groups, some demographic differences linked to the nature of the day hospital program emerged, as it is more focused on severe restrictive behaviors. Examining the psychopathology scores, differences were found only for eating psychopathology, with day hospital patients reporting higher scores due to their greater clinical severity. See Table 4.

Discussion

The present study explored the psychological effects of a year of exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic in patients with EDs and their HS by comparing them to a group of CW. Our main hypothesis was the presence of different posttraumatic responses in individuals with EDs, their HS, and a sample of CW. Our data showed that participants with EDs reported higher scores in all the subscales, indicating the presence of more specific posttraumatic responses to distressing experiences like the COVID-19 pandemic [20], and corroborating the evidence of the relationships between traumatic events and general and ED psychopathology [33].

As expected, no differences emerged between the HS and CW groups regarding specific and general symptomatology. However, HS reported higher scores than CW for avoidance with no differences between HS and ED patients. Interestingly, avoidance has been reported to be a core construct in posttraumatic symptomatology in EDs, implicating its role in the activation of ED and trauma-related symptomatology [34]. While the existing literature has already suggested the presence of posttraumatic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in patients with EDs [35], our data provide a specific profile for their healthy sisters that could encourage further study about the effects of environmental adversities in subjects with EDs and its possible effects on genotype [36]. This interaction might not only be characterized by the presence of different psychological and temperamental traits [23, 36] but also by the presence of neurobiological differences that might need to be evaluated [37]. Our data show that traumatic events might produce similar posttraumatic symptomatology in the healthy sisters of patients with EDs, even if they do not reach a clinically significant level of posttraumatic disorder. Biological and environmental interactions are still an open field of research in EDs, but a growing body of data highlights the role of these factors in the differences in life trajectories of sisters with and without EDs [38]. Indeed, several models have been proposed to explain the connections between traumatic or adverse events and EDs [39], and a wealth of data corroborates the presence of a blunted stress response in distressed patients with EDs [37, 40]. From this perspective, COVID-19 may be considered a psycho-social stressor with possible cognitive and emotional effects in ED patients [30, 41]. Moreover, another noteworthy result was the presence of an association between posttraumatic symptoms and interpersonal sensitivity in both patients and their sisters. This association underlined the possible role of insufficient social support or social abilities in the face of complex events [35]; these factors have already been cited as core elements in the development and maintenance of eating psychopathology [42,43,44], and should be explored in more detail in patients’ sisters in future studies. Laboratory tasks have explored and reported specific negative effects of social interaction in individuals with EDs, indicating the presence of interpretation bias, fear for negative evaluations, and less physiological arousal in social interactions [43, 45,46,47]. Conversely, depressive symptoms have been confirmed as related to posttraumatic symptomatology in community samples during the COVID-19 pandemic [48], with differences in patients which could be explained by the presence of higher scores in women with EDs for both depressive and posttraumatic symptomatology. Finally, only ED patients showed an association between posttraumatic symptoms and obsessive-compulsiveness; however, this is in line with previous literature about the pandemic’s role in exacerbating general and ED symptomatology in ED patients [6].

Looking at clinical features, several connections have been found between posttraumatic symptoms and binge or compensatory behaviors in patients with ED. These correlations are consistent with the existing literature about trauma in EDs, the hypothesis being that they might be a mental escape from negative affects [49]. Interestingly, these data have been reported by different population studies as effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, even in the general population [50, 51]. Moreover, while these elements have already been classified as fundamental by trauma-informed treatments, there is still work to be done in their integration into evidence-based treatments [52]. These data corroborate the implementation of specific interventions focused on the development of effective and adaptive strategies to cope with life’s adversities and engaging with valued activities to help those struggling with EDs to survive in years to come.

Strength and limits

The cross-sectional and self-reported nature of the questionnaires limits the reliability of the results, even if the differences between the groups are robust. However, while the exclusion of sisters with present or past histories of psychiatric conditions might improve the statistical strength of our results by clearing the samples of confounders, it might also be considered a limit for the generalizability of the study. In addition, the generalizability is further restricted by the exclusion of men. Other information, such as the participants’ occupations and the duration of their EDs, is missing from this study and should be considered in the future. Moreover, future studies should separate the first national lockdown of the spring of 2020 from the following partial or total lockdown conditions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study shows the presence of a psychological impairment clinically defined as posttraumatic symptomatology in patients with EDs after one year of containment measures to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, it also indicates the shared role of interpersonal sensitivity in ED patients and their healthy sisters in the development of posttraumatic psychological responses linked to stressful events, as well as the specific role of obsessive–compulsive and depressive symptoms in individuals with and without EDs. These results corroborate evidence of the role of the interaction between biological substrates and non-environmental features linked to adversity in the development and maintenance of EDs. However, more evidence—including data from men—is needed for more robust generalizability.

What is already known on this subject?

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated ED psychopathology in the general population with an increase in the request for specific treatments. Patients with an ED presented a specific profile associated with traumatic events that might be considered a vulnerability aspect of this increase in prevalence.

What this study adds?

This study evaluates the effects of exposure to the constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic 1 year after its beginning in a sample of women (ED patients, their healthy sisters, and community women), examining psychological features that might play a role in treatment approaches and in the comprehension of the pandemic’s psychological effects. Our data show the possible role of interpersonal sensitivity in the psychological burden of patients and families; in addition, it indicates that depression plays a role in the posttraumatic symptomatology of community women, providing a possible focus of investigation.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Todisco P, Donini LM (2021) Eating disorders and obesity (EDO) in the COVID-19 storm. Eat weight Disord 26:747–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00938-z

Sideli L, Lo Coco G, Bonfanti RC et al (2021) Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on eating disorders and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev 29:826–841. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2861

Cook B, Mascolo M, Bass G et al (2022) Has COVID-19 complicated eating disorder treatment? an examination of comorbidities and treatment response before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 24:39313

Masiero M, Mazzocco K, Harnois C et al (2020) From individual to social trauma: sources of everyday trauma in italy, the US and UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Trauma Dissociation 21:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2020.1787296

Jiang W, Ren Z, Yu L et al (2020) A network analysis of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and correlates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry 11:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.568037

Monteleone AM, Marciello F, Cascino G et al (2021) The impact of COVID-19 lockdown and of the following “re-opening” period on specific and general psychopathology in people with eating disorders: the emergent role of internalizing symptoms. J Affect Disord 285:77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.037

Touyz S, Lacey H, Hay P (2020) Eating disorders in the time of COVID-19. J Eat Disord 8:8–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00295-3

Rodgers RF, Lombardo C, Cerolini S et al (2020) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorder risk and symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 53:1166–1170. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23318

Linardon J, Messer M, Rodgers RF, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M (2022) A systematic scoping review of research on COVID-19 impacts on eating disorders: a critical appraisal of the evidence and recommendations for the field. Int J Eat Disord 55:3–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23640

Termorshuizen JD, Watson HJ, Thornton LM, Borg S, Flatt RE, MacDermod CM, Harper LE, van Furth EF, Peat CM, Bulik CM (2020) Early impact of COVID-19 on individuals with self-reported eating disorders: a survey of ~1,000 individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. Int J Eat Disord 53(11):1780–1790. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23353

Monteleone AM, Cascino G, Marciello F et al (2021) Risk and resilience factors for specific and general psychopathology worsening in people with eating disorders during COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective Italian multicentre study. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01097-x

Devoe DJ, Han A, Anderson A et al (2022) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorders: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23704

Dalle Grave R, Dalle Grave A, Bani E, Oliosi A, Conti M, Dametti L, Calugi S (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on intensive cognitive behavioral therapy outcomes in patients with anorexia nervosa—A cohort study. Int J Eat Disord. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23765

Monteleone P (2021) Eating disorders in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic: what have we learned? Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:10–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312381

McCombie C, Austin A, Dalton B et al (2020) “Now it’s just old habits and misery”—understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with current or life-time eating disorders: a qualitative study. Front Psychiatry 11:1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589225

Zeiler M, Wittek T, Kahlenberg L et al (2021) Impact of COVID-19 confinement on adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa: a qualitative interview study involving adolescents and parents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084251

Rodríguez-Quiroga A, MacDowell KS, Leza JC et al (2021) Childhood trauma determines different clinical and biological manifestations in patients with eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord 26:847–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00922-7

Favaro A, Dalle Grave R, Santonastaso P (1998) Impact of a history of physical and sexual abuse in eating disordered and asymptomatic subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 97:358–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10015.x

Lo Sauro C, Ravaldi C, Cabras PL et al (2008) Stress, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and eating disorders. Neuropsychobiology 57:95–115. https://doi.org/10.1159/000138912

Cooper M, Reilly EE, Siegel JA et al (2020) Eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine: an overview of risks and recommendations for treatment and early intervention. Eat Disord 30:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2020.1790271

Kanakam N, Krug I, Raoult C et al (2013) Social and emotional processing as a behavioural endophenotype in eating disorders: a pilot investigation in twins. Eur Eat Disord Rev 21:294–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2232

Tenconi E, Santonastaso P, Degortes D et al (2010) Set-shifting abilities, central coherence, and handedness in anorexia nervosa patients, their unaffected siblings and healthy controls: exploring putative endophenotypes. World J Biol Psychiatry 11:813–823. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622975.2010.483250

Maon I, Horesh D, Gvion Y (2020) Siblings of individuals with eating disorders: a review of the literature. Front Psychiatry 11:1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00604

Parsons H, Murphy B, Malone D, Holme I (2021) Review of Ireland’s first year of the COVID-19 pandemic impact on people affected by eating disorders: ‘behind every screen there was a family supporting a person with an eating disorder.’ J Clin Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153385

Fairburn C, Beglin S (1994) Assessment of eating disorder: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 16:363–370

Calugi S, Milanese C, Sartirana M et al (2017) The eating disorder examination questionnaire: reliability and validity of the Italian version. Eat Weight Disord Anorex Bulim Obes 22:509–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0276-6

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K et al (1974) The hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci 19:1–15

Carrozzino D, Vassend O, Bjørndal F et al (2016) A clinimetric analysis of the hopkins symptom checklist (SCL-90-R) in general population studies (Denmark, Norway, and Italy). Nord J Psychiatry 70:374–379

Santonastaso P, Saccon D, Favaro A (1997) Burden and psychiatric symptoms on key relatives of patients with eating disorders: a preliminary study. Eat Weight Disord Anorex Bulim Obes 2:44–48

Nisticò V, Bertelli S, Tedesco R et al (2021) The psychological impact of COVID-19-related lockdown measures among a sample of Italian patients with eating disorders: a preliminary longitudinal study. Eat Weight Disord Anorex Bulim Obes 26:2771–2777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01137-0

Craparo G, Faraci P, Rotondo G, Gori A (2013) The impact of event scale–revised: psychometric properties of the Italian version in a sample of flood victims. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 9:1427

Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S (2003) Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale—revised. Behav Res Ther 41:1489–1496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010

Meneguzzo P, Cazzola C, Castegnaro R et al (2021) Associations between trauma, early maladaptive schemas, personality traits, and clinical severity in eating disorder patients: a clinical presentation and mediation analysis. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661924

Liebman RE, Becker KR, Smith KE et al (2021) Network analysis of posttraumatic stress and eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adults exposed to childhood abuse. J Trauma Stress 34:665–674. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22644

Monteleone AM (2021) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorders: a paradigm for an emotional posttraumatic stress model of eating disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 51:84–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.05.009

Rozenblat V, Ong D, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M et al (2017) A systematic review and secondary data analysis of the interactions between the serotonin transporter 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and environmental and psychological factors in eating disorders. J Psychiatr Res 84:62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.023

Meneguzzo P, Mancini C, Terlizzi S et al (2022) Urinary free cortisol and childhood maltreatments in eating disorder patients: new evidence for an ecophenotype subgroup. Eur Eat Disord Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2896

Bakalar JL, Shank LM, Vannucci A et al (2015) Recent advances in developmental and risk factor research on eating disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0585-x

Trottier K, MacDonald DE (2017) Update on psychological trauma, other severe adverse experiences and eating disorders: state of the research and future research directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19:1–9

Monteleone AM, Monteleone P, Volpe U et al (2018) Impaired cortisol awakening response in eating disorder women with childhood trauma exposure: evidence for a dose-dependent effect of the traumatic load. Psychol Med 48:952–960. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002409

Castellini G, Cassioli E, Rossi E et al (2020) The impact of COVID-19 epidemic on eating disorders: a longitudinal observation of pre versus post psychopathological features in a sample of patients with eating disorders and a group of healthy controls. Int J Eat Disord 53:1855–1862. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23368

Hartmann A, Zeeck A, Barrett MS (2010) Interpersonal problems in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 43:619–627. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20747

Meneguzzo P, Collantoni E, Bonello E et al (2020) The predictive value of the early maladaptive schemas in social situations in anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2724

Solmi M, Collantoni E, Meneguzzo P et al (2018) Network analysis of specific psychopathology and psychiatric symptoms in patients with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 51:680–692. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22884

Rowlands K, Grafton B, Cerea S et al (2021) A multifaceted study of interpersonal functioning and cognitive biases towards social stimuli in adolescents with eating disorders and healthy controls. J Affect Disord 295:397–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.013

Harrison A (2021) Experimental investigation of non-verbal communication in eating disorders. Psychiatry Res 297:113732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113732

Monteleone AM, Treasure J, Kan C, Cardi V (2018) Reactivity to interpersonal stress in patients with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using an experimental paradigm. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 87:133–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.002

Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D et al (2021) Trauma-spectrum symptoms among the Italian general population in the time of the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur J Psychotraumatol. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1855888

Witte TH, Jordan HR, Michael ML (2018) Posttraumatic stress symptoms and binge eating with mental escape features. J Loss Trauma 23:684–697

Christensen KA, Forbush KT, Richson BN et al (2021) Food insecurity associated with elevated eating disorder symptoms, impairment, and eating disorder diagnoses in an American University student sample before and during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Eat Disord 54:1213–1223. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23517

Pompili S, Di Tata D, Bianchi D et al (2022) Food and alcohol disturbance among young adults during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: risk and protective factors. Eat weight Disord 27:769–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01220-6

Brewerton TD (2019) An overview of trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma 28:445–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2018.1532940

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Padova within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. PM has received research support from Fondazione Emanuela, Luigi e Maria Dalla Vecchia Onlus and by the “Department of excellence 2018–2022” initiative of the Italian Ministry of education (MIUR) awarded to the Department of Neuroscience—University of Padua.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: PM, AS, EC, PS; methodology: PM, PS; software: PM; formal analysis: PM; investigation: PM, AS, LM, EC, PS; resources: AS, EC, PS; data curation, PM; writing—original draft preparation: PM, LM; writing—review and editing: AS, EC, PS; visualization: PM; supervision: AS, EC, PS; project administration: AS, PS; funding acquisition: AS, EC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee of Vicenza.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meneguzzo, P., Sala, A., Merlino, L. et al. One year of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with eating disorders, healthy sisters, and community women: evidence of psychological vulnerabilities. Eat Weight Disord 27, 3429–3438 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01477-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01477-5