Abstract

Purpose

Past and recent immigration flows have made societies increasingly more diverse, with important implications for the economy. This article investigates the empirical relationship between ethnic, and birthplace immigration diversity on job creation and entrepreneurship.

Design/methodology/approach

We use multilevel modelling and the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor adult population survey across 60 countries from 2001 to 2018.

Findings

As earlier literature, we find that people have a higher probability of becoming entrepreneurs in more ethnically diverse countries. Nonetheless, businesses located in more ethnically diverse countries hire fewer employees. Businesses, on the other hand, create more jobs in countries with a higher proportion of skilled and unskilled immigrants due to skill complementarity.

Research originality

Contrary to commonly held views, our findings suggest that ethnic and immigration diversity have opposing effects on entrepreneurship and provide important insights into the debate over the economic impact of immigration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The number of international migrants has more than doubled worldwide since the 1960s, with some areas such as OECD countries experiencing a threefold increase in the share of foreign-born people in the workforce (Alesina et al., 2016). The higher diversity resulting from historical and recent population mobility presents many challenges. The economics literature has found that more ethnically diverse countries tend to have poor economic performance, growth, investments and are more prone to conflict (Easterly & Levine, 1997; Gören, 2014). However, contrasting views, stemming mostly from the entrepreneurship literature, suggest that ethnic and immigration diversity is not necessarily harmful to growth as it can promote the creation of jobs, businesses and social mobility (Danes et al., 2008).

Several reasons can explain the contrasting views on the effects of population diversity. Much of the literature has focused on the short-term impacts of increased population diversity, such as on start-ups, overlooking whether these businesses will survive or create jobs. Also, ethnic and immigrant groups have typically been analysed in isolation, instead of assessing the characteristics that these groups may have in common with the rest of the population (Ram et al., 2010). But perhaps the most important factor limiting our understanding is that the effects of ethnic and immigrant diversity have been analysed separately, while keeping the narratives of how population diversity affects entrepreneurship intertwined (Hlepas, 2013). The empirical under-exploration of whether ethnic and immigrant diversity affects entrepreneurship differently is also reflected in the lack of theoretical frameworks examining these dimensions simultaneously. Although the multiple dimensions of ethnic and migration diversity might overlap, their effects on entrepreneurship, and more broadly, on development, might not necessarily be similar (Desmet et al., 2017). For instance, new cross-country data show that birthplace immigrant diversity is surprisingly uncorrelated to ethnic diversity, contradicting the common assumption that the effects of higher diversity necessarily go hand in hand (Alesina et al., 2016). Similarly, a number of management and economic studies suggest that immigration diversity and increased shared of immigrants might have different effects on performance and the economy (Milliken & Martins, 1996; Portes et al., 2002).

This article examines the effect of ethnic and immigrant diversity on entrepreneurship and job creation. To this end, we analyse the publicly available Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) adult population survey across 60 countries from 2001 until 2018. GEM, the largest comparative international survey of entrepreneurial activity, allows us to simultaneously consider both individual and environmental characteristics that affect the probability of becoming an entrepreneur. To this end we use multilevel modelling, and consider respondents’ sex, education, family income and access to entrepreneurial networks. We also analyse the characteristics of the country in which these respondents reside, such as the overall population share of immigrants, the Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, and institutional variables that reflect the ease of doing business. Crucially, we also consider the ethnic fractionalization index proposed by Alesina et al. (2003) and the index of immigrant birthplace diversity proposed by Alesina et al. (2016).

This article analyses two important aspects in the literature of entrepreneurship. First, the article offers the first systematic analysis of whether the association between entrepreneurial activity and ethnic diversity differs from the association observed with immigrant birthplace diversity. To this end, the article builds on existing theories on population diversity and adds insights as to why within-country ethnic and immigrant diversity may have different effects on business creation and business survival. The goal is not to test whether ethnic minorities or immigrants are more likely to create businesses, an issue that has been explored extensively (Basu & Altinay, 2002; Kerr & Kerr, 2020).Instead, we seek to empirically assess the net effect that within-country diversity has on entrepreneurial activities, while also considering other important people’s characteristics and differences in country-level settings. Second, another important and overlooked issue that we asses is the impact of within-country diversity on job creation. Thus, the article provides a comprehensive empirical overview of whether diversity helps people to identify business opportunities, whether these are seized, and whether businesses grow and survive. This granular view is particularly valuable for policymaking aimed at fostering both entrepreneurship and job creation.

The article continues as follows. The next Section reviews the existing literature and develops the hypotheses to test on the effects of ethnic and immigrant diversity on entrepreneurship. Then, the paper shows the data sources, the multilevel method, show the results and robustness checks. The last Section presents our conclusions.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Ethnic diversity

The literature on entrepreneurship has traditionally focused on attributes that shape people’s ability to recognise business opportunities and act on them, such as preferences, motivations, networks, and skills. Nonetheless, theoretical models of entrepreneurship such as the knowledge spill-over theory of entrepreneurship (KSTE), also explicitly acknowledge that people’s entrepreneurial decisions are also affected by the economic and demographic structure of their country of residence including the degree of ethnic diversity (Acs et al., 2013; Audretsch & Keilbach, 2007; Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990).

Ethnicity is understood as the shared social traits and common history that groups have, or what others think of them as having (Yinger, 1985). People living in more ethnically diverse countries might enjoy several advantages that are conducive to entrepreneurship. For instance, people sharing ethnic ties with several members of the community can increase their sense of belonging and desire to serve fellow community members. Ethnic entrepreneurs in the community can also serve as role models inspiring others, whether ethnic fellows or not, to see entrepreneurship as a viable occupation (Masurel et al., 2004). Moreover, dealings based on coethnic loyalties can increase the chance of business creation and mutual survival by providing access to informal networks that can facilitate raising start-up capital, identify potential clients, and create strong demand for ethnic products (Somashekhar, 2019). For this reason, ethnic businesses tend to cluster strategically, typically in urbanised settings (Aldrich et al., 1983; Volery, 2007). Nonetheless, since these businesses typically face tough competition from other similar small businesses, they tend to be small in size, particularly if ethnic minorities face credit constraints that makes them rely more on self-employment or family members (Bruder et al., 2011). For that reason, the literature has argued that ethnic diversity although conducive to foster entrepreneurship in the short- and long-run, does not necessarily lead to more job creation (Cavalluzzo & Wolken, 2005).

Immigrant diversity and share of immigrants

Despite the sharp increase in migration flows, and the rich and vibrant research on ethnic diversity, surprisingly not much is known about the net effect that immigrants and the associated increase in population diversity have on entrepreneurship over time (Kemeny, 2017). People born in different countries have been educated under different systems, and possibly possess different skills and entrepreneurial values than groups raised and educated in the same country (Alesina et al., 2016). Thus, the effect of immigrant diversity on entrepreneurship requires careful examination and to be distinguished from the effects of ethnic diversity. A few notable studies using the KTSE theoretical framework have found that as immigrant diversity increases, so do new markets offering traditional products, and skill complementarity all beneficial for productivity and entrepreneurship of both immigrants and the native population (Rodríguez-Pose & Hardy, 2015; Saxena, 2014). Skill complementarity refers to finding workers with the levels of skills and expertise needed by entrepreneurs’ technology and capital. This form of skill complementarity has the potential to boost efficiency, productivity and growth (Krusell et al., 2000).

Another large strand of the literature has found that immigrants boost early-stage entrepreneurship as they tend to be more likely to have their own business than the native population (Desiderio & Salt, 2010). However, other studies are more cautious about the potential effect of immigrant diversity, and point out that the ‘immigrant entrepreneur’ phenomenon that has been observed is a result of constrained choices, such as the labour discrimination that immigrants might face (Vandor & Franke, 2006). Since immigrants often also face credit constraints and a fiercely competitive environment, their businesses tend to be smaller than those of the native population and have low chances of surviving (Cavalluzzo & Wolken, 2005). Moreover, even though immigrant entrepreneurs might benefit from coethnic networks, these bonds might be insufficient for entrepreneurial success (Moyo, 2014). Business survival will be threatened, for instance, if their market is fragmented without the critical mass required, or if the purchasing power of their clients, such as other minority groups, is weak (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990). In this sense, it is unclear whether increased immigrant diversity will necessarily have an overall positive effect on business survival or job creation.

A burgeoning literature has also pointed out that it is important to distinguish between increased immigration diversity and the share of immigrants, as surprisingly both variables can have different effects on the economy (Alesina et al., 2016). Several studies have found that a higher share of immigrants is beneficial for performance and perhaps job creation, whilst immigrant diversity has decreasing returns as it can worsen team cohesion and coordination costs (Milliken & Martins, 1996). The social identity theory provides support for arguments claiming that population diversity might be detrimental to performance (Tajfel & Turner, 2004). According to this theory, the more diverse an organization is, the higher its costs of cooperation and communication (Cooke & Kemeny, 2017).

Other economic studies have found suggestive evidence that a higher share of immigrants is beneficial for both the creation of jobs and the local economy. For instance, a higher share of immigrants is associated with more border-crossing business activities between immigrants’ country of origin and destination (Portes et al., 2002). Also, a higher share of immigrants can also beneficial for new or existing business in the country of destination as having a wider pool of immigrants increases the chances of businesses finding suitable employees with desired skills. For instance, Ottaviano and Peri (2006) find that a higher share of the immigrant population in metropolitan areas in the USA has led to an increase in the salary of native workers. This effect is thanks to the boost in productivity derived from the skill complementarity that immigrants bring, as theoretically suggested by Roback (1982). Other studies, conclude that immigrants boost the demand for goods and services in the places they move to, thereby increasing local business demand which can be beneficial for job creation, and with no strong evidence of detrimental effects on the salaries of native workers (Card, 1990).

Hypotheses

Based on the literature reviewed, we argue that a society that is ethnically diverse offers several opportunities for people to identify and pursue new businesses. Despite the challenges that minority groups might face, their coethnic bonds and shared values can substitute and overcome many of the constraints imposed by formal institutions (Szkudlarek & Wu, 2018). The theories examined, such as the skill complementarity theory proposed by Roback (1982) and in particularly the KSTE framework, explicitly agree that population diversity has the potential to foster early-stage entrepreneurship. Nonetheless it is worth noting that none of the existing theories explicitly distinguish the effects that might be brought by ethnic and immigrant diversity. However, by synthesising different, yet disjointed, theories on diversity, we expect the effects of ethnic diversity on entrepreneurship to be different from those of immigrant diversity. Immigrant diverse societies have compound cultural ties and trading networks with other countries which can increase business opportunities, although these trade bonds and small-scale networks with international markets do not necessarily guarantee business survival (Moyo, 2014). Besides, studies across various disciplines (economics, entrepreneurship and management) suggest that immigrant diversity has decreasing returns, because of the costly and complicated coordination across people with different cultural values, languages and skills (Nikolova & Simroth, 2013). Hence, immigrant diversity is unlikely to necessarily be conducive to business survival or growth. This is not to say that immigrants are not vital to the economy. In fact, countries with a higher share of immigrants are likely to boost their labour supply and enable businesses to access a pool of workers that might either complement the skills of native workers or fill essential gaps (Roback, 1982). This skill complementarity can increase productivity and aid businesses expansion. Based on this discussion we formulate the following hypotheses.

-

Hypothesis 1a: Ethnic diversity increases the likelihood of a country having more start-ups and established businesses.

-

Hypothesis 1b: Immigrant diversity decreases the likelihood of a country having more start-ups and established businesses.

-

Hypothesis 2a: Ethnic diversity hinders business job expansion.

-

Hypothesis 2b: Immigrant diversity hinders business job expansion.

-

Hypothesis 3a: A higher share of immigrants in the population increases the likelihood that businesses create more jobs.

-

Hypothesis 3b: A higher share of immigrants in the population increases the likelihood that businesses create more jobs because of skill complementarity.

Data and method

We test all our hypotheses using the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) adult population survey. GEM is the largest comparable cross-country survey on entrepreneurship, drawing nationally representative samples each year. In total we analyse 60 out of the 89 countries that have taken part in these surveys for at least one year during the 2001–2018 period, capturing both developed and developing regions. We exclude those countries for which either we have no information on ethnic, or immigration diversity, nor a full set of controls as mentioned below.

Dependent variables

To test hypotheses 1a and 1b, we use as a dependent variable whether the GEM respondent is engaged in early-stage entrepreneurial activity. Separately, we also use as a dependent variable whether the respondent has an established business. Early-stage and established businesses are defined by GEM as follows (Reynolds et al., 2005):

-

Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity includes entrepreneurs aged 18–64 who either have a start-up or a young business. Start-ups are people who are actively setting up a new business that they will own and manage, but who have not received salaries or any other payments for more than three months. Young businesses are those who have paid salaries or any other payments to their owners for more than three months and up to 3.5 years.

-

Established businesses are those who have paid salaries, or any other payments, to their owners for more than 3.5 years.

We test hypotheses 2a-3b using as dependent variable the number of employees hired by young businesses, and separately the number of employees hired by established businesses. Both of these variables exclude the owners of the firm.

Table 1 shows that 1,331,728 people were interviewed by the GEM network across the 60 countries considered during 2001–2018. From those, 7% of the sample have a start-up, another 5% have a young business, and 8% own an established business. The average number of employees hired by young businesses is 5.44, while the number for established businesses is slightly lower at 5.05.

Independent variables

The publicly available GEM surveys analysed here do not include respondents’ ethnicity or birthplace. Thus, we complement the GEM survey with three external diversity indices for each country, as explained next.

Measuring ethnic diversity

We use the ethnic fractionalization index proposed by Alesina et al. (2003) which has dominated the analysis of ethnic diversity. As shown in Eq. (1), this index uses the Herfindahl measure, which captures the probability that two people drawn randomly from within a country are from different ethnic groups.Footnote 1The index ranges from zero, when all belong to the same ethnic group, to a maximum of one, where everyone belongs to different groups. Ethnic groups are identified on the basis of both linguistic characteristics (for most of Africa and Europe) and racial characteristics (for most of Latin America), an approach commonly used by ethnologists and anthropologists.

where sgj is the share of group g (g = 1…N) in country j.

Measuring birthplace immigration diversity

To measure immigrant diversity we use the index proposed by Alesina et al. (2016). This index is based on people’s birthplace, for the workforce of 195 countries in the years 1990 and 2000. The index also uses the Herfindahl measure, hence, it estimates the likelihood that two people drawn randomly from the population have two different countries of birth. Immigrants are identified as foreign-born people aged 25 or older. This immigration index uses the Artuc et al. (2015) dataset, which provides bilateral data on migration across 195 countries.

This birthplace immigration index can be separated into two: the birthplace immigrant diversity and the share of immigrants in the population. Both statistics can be broken down for skilled and unskilled immigrants. Alesina et al. (2016) show that contrary to widely made assumptions, the immigrant diversity index is uncorrelated to the various ethnic diversity indices proposed in the literature (see Table 2). This lack of correlation might explain why, in contrast to ethnic diversity indices, the population share of immigrants has been found to be positively associated with income per capita in cross-country regressions (Alesina et al., 2016). To the best of our knowledge, no cross-country analysis has previously used this new immigration diversity index to analyse the impact on entrepreneurship and job creation.

Note that all the diversity indices used are for the year 2000, that is right before the period of analysis. As Alesina et al. (2003) explain, this is reasonable, and a sound approach given that population diversity is sufficiently stable over a 20-year horizon. Previous cross-country studies measure these diversity indices pre-dating the dependent variable without capturing changes in diversity over time. We follow the same approach here. Although we will not fully capture how recent changes in diversity brought by constant migration movements affect entrepreneurship, by using diversity measures that immediately precede the entrepreneurial statistics we sidestep potential endogeneity issues.

Entrepreneurship and ethnic and immigrant diversity indices

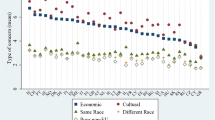

We start by providing some insights into the relationship between entrepreneurship and diversity. For this, we estimate the average rate of early-stage of entrepreneurial activity for each country during the entire period 2001–2018 and plot it against the ethnic and immigrant diversity indices. Figure 1 shows there is a positive and statistically significant correlation between the entrepreneurship rate (for start-ups and established businesses) during 2001–2018 and the index of ethnic diversity, whereas this relationship is weak and non-statistically significant for the index of immigration diversity. Similarly, Fig. 2 shows there is a negative and statistically significant correlation between the country’s average number of employees hired by businesses during the period 2001–2018, and the ethnic diversity index. This correlation is weak and non-statistically significant for the immigrant diversity index.

Although these aggregate patterns at country-level are suggestive of the associations between ethnic and immigrant diversity and entrepreneurship, they suffer from two major limitations. First, people’s decision to become an entrepreneur and their entrepreneurial success is not only affected by national context, but also by individual characteristics. Thus, if we aggregate average trends of entrepreneurship across countries, we will be unable to take into account the important role of how people’s characteristics affect entrepreneurship. Second, the aggregation of data at country-level can result in the loss or even concealment of the degree and size of the association between diversity and entrepreneurship at the individual-level. That is, correlations observed at the aggregate level can be quite different in size and direction to the correlation found at the individual-level. This means that one cannot make reliable inferences from aggregate trends from the country-level to the individual-level, for instance, otherwise one would risk suffering the so-called ecological fallacy. To address all these concerns, in our analysis we include other important individual and country-level characteristics and multilevel analysis.

Country-level variables

At country-level, we consider Gross National Income (GNI) per capita in constant terms at purchasing power parity, which serves as a proxy for the country’s market size and level of development. We include this country-level control as it is known that the correlation between the ethnic fractionalization index and other development measures lose significance when considering countries’ income per capita (Alesina & La Ferrara, 2005). We also control for other important national determinants of entrepreneurship and job creation. We add the credit available at the country-level (as a share of the Gross Domestic Product) which has been shown to influence the creation, survival of businesses as well as job expansion (Gutiérrez-Romero, 2021a). We also add two proxies for ease of doing business in the respondents’ country of residency. These two proxies are the number of procedures and the time that it takes to register a new business gathered by the World Bank. Business regulation has been argued to be an important determinant of entrepreneurship, whether in the formal or informal market (Djankov et al., 2002; Gutiérrez-Romero, 2021b). We include all these country-level controls for the year 2000 only to avoid potential endogeneity concerns.Footnote 2 We also measure these four country-level controls in logarithm terms to be able to address potential heteroscedasticity issues.

We also control for regional fixed effects (whether in Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, North America, Oceania, or the Middle East), as ethnic diversity is correlated regionally (Alesina et al., 2003). We add fixed-year effects to take into account other time-variant factors, such as shocks to the economy, which might have occurred during the period of analysis.

Individual-level variables

At the respondent-level, we include whether the respondent has entrepreneurial networks. To this end, we use a binary variable based on the ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response to the GEM survey question: ‘Do you personally know someone who started a business in the past two years?’. We include this variable, as role models contribute to enriching people’s social capital and increasing the chances of business survival (Burt, 2005).

We also add a binary variable identifying whether the respondent is a moneylender, better known as a business angel in the GEM literature. We do so as informal financial networks are vital for business survival, particularly in diverse environments (Bruder et al., 2011). We identify business angels as respondents who ‘over the past three years, provided funds for a new business’ and ‘lent these funds to non-family members’.

We include the respondents’ gender and age, since they influence access to financial networks and entrepreneurial engagement (Runyan et al., 2006). We also add the respondents’ family household income, as previous research shows this variable affects whether businesses are created, survive and expand (Dollinger, 2003). GEM records income in tertiles, meaning whether respondents stated their family income falls in the lowest, middle or top third of the family income distribution of the country and year where the interview took place. Following the literature on human capital, we include respondents’ education level. This variable measures whether respondents have post-secondary education or not. We do not predict how education will affect entrepreneurship, as the international evidence is rather mixed (Lee & Tsang, 2001). Last, we include people’s self-reported business skills, known to be essential for business survival and job expansion (Cuervo, 2005). This variable is based on the ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer to the following GEM question: ‘Do you have the knowledge, skill and experience required to start a new business?’.

Tables 1 and 2 show the summary statistics and correlations between the ethnic, and the immigration diversity indices used. Table A.1 shows the diversity indices, the share of immigrants, and entrepreneurship statistics used.

Method: Multilevel analysis

To assess how ethnic and immigration diversity affect individual entrepreneurial behaviour, we use a series of multilevel linear regressions. This specification, also known as the panel random effects, hierarchical or mixed model, simultaneously takes into account individual- and country-level characteristics that are time-variant and time-invariant (Bell & Jones, 2015). Our dataset is a repeated cross-sectional survey of 1,331,728 adults across up-to 60 countries over 2001–2018. That is, the survey respondents are nested in their respective countries of residence, which are more likely to behave similarly to other respondents living in the same country than respondents in other countries. This type of dependency invalidates commonly used regression models such as Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), which requires the errors to be unrelated across units or levels (Mehmetoglu & Jakobsen, 2016). For this reason, multilevel, multi-country analysis has been widely used in the entrepreneurship literature and to ensure unbiased estimation of cross-level effects (Kibler & Kautonen, 2016).

Equation (3) shows how our multilevel linear model takes into account that GEM survey respondents are nested in their respective country of residency, while taking into account the individual characteristics (or so-called level-1 characteristics) and country-characteristics (level-2).

Our dependent variable Entrepreneur takes the value of 1 in case the respondent i in country j at year k is engaged in early-stage entrepreneurship, and takes the value of 0 if not. Separately, we also analyse respondents who own established businesses. Where u and e are the error terms at country and individual level. We add X, a set of respondents’ characteristics and Year fixed effects. Vector C represents the country’s characteristics. This vector includes the country’s GNI per capita, credit (as a percentage of GDP), number of procedures and the time that it takes to open a business, all measured in logarithm form. As mentioned earlier, all these country-level controls refer to the year 2000, slightly before our period of analysis to avoid endogeneity. We also add regional fixed effects. We add the ethnic fractionalization index, and the immigrants’ birthplace diversity indices. Again, note that these indices do not change over time, but refer to before our period of analysis, which helps to mitigate further having potential endogeneity concerns. Following Alesina et al. (2016), we include all these diversity indices and the population share of immigrants simultaneously to capture their potential distinct effects.

To avoid heteroscedasticity, we estimate all our models with robust standard errors. It is worth noting that the R-squared in most linear probability models like ours does not have the usual standard interpretation when the dependent variable is binary and the regressors are continuous.Footnote 3 In linear probability models, the R-squared however can be interpreted as the difference between the average predicted probability in the two groups being analysed.

Results and discussion

Business creation and survival

Table 3 displays the multilevel regression coefficients of the specification shown in Eq. (3). Supporting hypotheses 1a we find that the ethnic fractionalization index is positively associated with both the country’s average probability that people will have an early-stage business (columns 1–3) as well as an established business (columns 4–6). This positive association is robust to excluding or adding different measures of immigrant birthplace diversity indices and the population share of immigrants. Although GEM does not follow exactly the same business over time, a higher probability of having an established business of 3.5 years or older, we interpret as a rough proxy of business survival.

Also in line with hypotheses 1b immigrant birthplace diversity reduces both the country’s average probability of having a start-up and established business (Table 3, columns 1–6). That is the case if focusing on immigrant diversity for skilled or unskilled people only.

Our findings are robust to simultaneously considering the individual characteristics of respondents, and other country characteristics. In this regard, all individual regression coefficients are in line with our expectations. Similarly, a higher number of procedures needed to register a new business reduces business creation. We also find that countries with higher GNI per capita, and credit available have lower average probability of opening businesses. This association might suggest that people might prefer to become employees rather than venturing into new businesses.

Job creation

To test hypotheses 2a, 2b and 3a we use as a dependent variable the number of employees hired. We analyse the number of employees hired by young businesses, and separately those hired by established businesses. We also use a linear multilevel model, as shown in Eq. (4).

Following GEM’s definition, the number of employees hired excludes the owner(s) of the firm. So, for businesses with no extra employees, the dependent variable takes the value of zero, meaning self-employed. We exclude from this analysis respondents who do not have any existing businesses, as well as start-ups, as these firms are in too early a stage. In our multilevel analysis we use the same controls as before, and add the industrial sector as this might influence the number of employees needed.

Table 4 shows the multilevel linear coefficients. Again, the individual and the country-level variables considered provide results consistent with our expectations. Supporting hypothesis 2a, we find that the index of ethnic fractionalization is negatively associated with the number of employees hired by young and established businesses. Similarly, the index of immigrant diversity is negatively associated with the number of employees hired by young and established businesses, although this effect is non-statistically significant. That is the case if using the index of immigrant diversity index for skilled or unskilled immigrants.

Supporting our hypothesis 3a, we find that a higher share immigrants increase job expansion of both young and established businesses (Table 4, columns 1–6). This is the case when considering the share of all immigrants, or only skilled or unskilled immigrants.

To more formally test that a higher share of immigrants boosts job creation due to skill complementarity, we add into our multilevel regressions an interaction term. This term interacts the population share of immigrants and a variable that measures the business industry’s intensity on employees with at least sixteen years of schooling. Ciccone and Papaioannou (2009) estimated this intensity in human capital for the 27 large manufacturing industries shown in Table A.2.Footnote 4 Focusing only on these 27 industries, Table 5 shows that the interaction coefficient is positive and statistically significant. Thus, this finding suggests that a higher population share of immigrants (both skilled and unskilled workers) is favourable for job creation, especially for industries that are more intensive in knowledge. This effect is statistically significant for both young firms (columns 1 and 2), and for businesses older than 3.5 years, (columns 2–4).

Conclusions

We analysed the association between ethnic and immigrant diversity and entrepreneurship. Using the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor adult population survey across 60 countries, we found three key insights.

First, in line with earlier literature, we found that ethnic diversity increases the country’s average probability of having start-ups (Masurel et al., 2004; Sobel et al., 2010). Second, the country’s average probability of having established business 3.5 years or older, which can be taken as a rough measure of business survival, is positively associated with ethnic diversity. Similarly, we found that immigrant diversity has a negative effect on country’s average probability of having businesses (start ups or established). However, that does not mean that immigration is detrimental for entrepreneurship. Our third key finding revealed that businesses in countries with higher share of skilled or unskilled immigrants are more likely to create more jobs. Our findings suggest that this positive effect on job creation is due skill complementarity. That is, businesses in a setting with a higher share of pool of immigrants find easier to create jobs because they it is easier to find a match for the wide range of skills they might need to complement their production and services offered. We showed that manufacturing industries more intensive in human capital created substantially more jobs, the higher the share of immigrants (whether skilled or unskilled), for early-stage and established businesses.

Our empirical analysis centred on pulling together various hypotheses on ethnic and immigrant diversity from well-known frameworks of entrepreneurship and organisations. We focused particularly on the skill complementarity, social identity and KSTE theories. Our analysis uncovered that the effects of ethnicity and immigrant diversity are quite distinct and deserve to be fully incorporated into both theoretical and empirical studies. Future theoretical research studies could extent existing theoretical frameworks to incorporate the behavioural and economic foundations that drive some of the effects that our study detected. We acknowledge that one of the limitations of our analysis is to have aggregate measures of ethnic and immigrant population diversity and that refer to 2000. Future empirical research could perhaps make use of more fine-grained data to understand how changes in ethnic and immigrant diversity of entrepreneurs or workers contribute to entrepreneurship and job creation over time.

Our results have important policy implications for countries seeking to toughen their immigration policies. Immigration policies need to consider the consequences of ethnic and immigrant diversity on job creation and entrepreneurship, all key drivers of growth. For instance, while some policymakers might be concerned about the extra demand for services and housing that may be associated from immigration, a higher share of immigrants boost job creation, thus being beneficial for the economy. Overall, our empirical findings provide a more nuanced understanding of the effects of ethnic and immigrant diversity.

Data availability

All data used was secured from publicly available secondary data. Replication material can be provided upon request.

Code availability

All code replication material can be provided upon request.

Notes

Alesina et al. (2003) used multiple sources but mainly the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Our findings and conclusions remain exactly the same if we measure all these country-level controls annually during the entire period of our analysis, 2001–2018.

Note that in other similar multilevel probit and logit models their measures of fit, such as the pseudo R-squared, do not have the same meaningful interpretation as the R-squared in OLS and does not range between 0 and 1 either.

These authors estimated these intensities using the USA integrated public use microdata series for 1980 and used this information as a proxy for the human capital intensity differences that these large manufacturing industries have in other countries.

Abbreviations

- GEM :

-

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor

- GNI :

-

Gross National Income

References

Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., & Lehman, E. (2013). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 757–774.

Aldrich, H. E., Cater, J. C., Jones, T. P., & McEvoy, D. (1983). From periphery to peripheral: The South Asian petite bourgeoisie in England. In I. H. Simpson & R. Simpson (eds.), Research in the Sociology of Work. Greenwich: JAI Press.

Aldrich, H. E., & Waldinger, R. (1990). Ethnicity and entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Sociology, 16(1), 111–135.

Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2005). Ethnic diversity and economic performance. Journal of Economic Literature, 43(3), 762–800.

Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 155–194.

Alesina, A., Harnoss, J., & Rapport, H. (2016). Birthplace diversity and economic prosperity. Journal of Economic Growth, 21(2), 101–138.

Artuc, E., Docquier, F., Özden, Ç., & Parsons, C. (2015). A global assessment of human capital mobility: The role of non-OECD destinations. World Development, 65(C), 6–26.

Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2007). The theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Journal of Management Studies, 44(7), 1242–1254.

Basu, A., & Altinay, E. (2002). The interaction between culture and entrepreneurship in London’s immigrant businesses. International Small Business Journal, 20(4), 371–393.

Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2015). Explaining fixed effects: Random effects modeling of time-series cross-sectional and panel data. Political Science Research and Methods, 3(1), 133–153.

Bruder, J., Neuberger, D., & Räthke-Döppner, S. (2011). Financial constraints of ethnic entrepreneurship: Evidence from Germany. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 17(3), 296–313.

Burt, R. S. (2005). Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital. Oxford University Press.

Card, D. (1990). The Impact of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami Labor Market. Industrial and Labor Relation, 43(2), 245–257.

Cavalluzzo, K., & Wolken, J. (2005). Small business loan turndowns, personal wealth and discrimination. Journal of Business, 78(6), 2153–2178.

Ciccone, A., & Papaioannou, E. (2009). Human capital, the structure of production, and growth. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(4), 66–82.

Cooke, A., & Kemeny, T. (2017). Cities, immigrant diversity, and complex problem solving. Research Policy, 46, 1175–1185.

Cuervo, A. (2005). Individual and environmental determinants of entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1(3), 293–311.

Danes, S., Lee, J., Stafford, K., & Heck, R. K. Z. (2008). The effects of ethnicity, families and culture on entrepreneurial experience: An extension of sustainable family business theory. Journal of Development Entrepreneurship, 13(3), 229–268.

Desiderio, M. V. & Salt, J. (2010). Main Findings of the Conference on Entrepreneurship and Employment Creation of Immigrants in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD.

Desmet, K., Ortuño-Ortín, I., & Wacziarg, R. (2017). Culture, ethnicity and diversity. American Economic Review, 107(9), 2479–2513.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). The regulation of entry. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 1–37.

Dollinger, M. J. (2003). Entrepreneurship: Strategies and Resources (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (1997). Africa’s growth tragedy: Policies and ethnic divisions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1203–1250.

Fearon, J. (2003). Ethnic and Cultural Diversity by Country. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 195–222.

Gören, E. (2014). How ethnic diversity affects economic growth. World Development, 59(C), 275–297.

Gutiérrez-Romero, R. (2021a). How does inequality affect long-run growth? Cross-industry, cross-country evidence. Economic Modelling, 95, 274–297.

Gutiérrez-Romero, R. (2021b). Inequality, persistence of the informal economy, and club convergence. World Development, 139(C), 105211.

Hlepas, N. (2013). Cultural diversity and national performance. Search working paper 5/06.

Kemeny, T. (2017). Immigrant diversity and economic performance in cities. International Regional Science Review, 40(2), 164–208.

Kerr, S.P., & Kerr, W. (2020). Immigrant entrepreneurship in America: Evidence from the survey of business owners 2007 & 2012. Research Policy, 49(3).

Kibler, E., & Kautonen, T. (2016). The moral legitimacy of entrepreneurs: An analysis of early-stage entrepreneurship across 26 countries. International Small Business Journal, 34(1), 34–50.

Krusell, P., Ohanian, L. E., Ríos-Rull, J. V., & Violante, G. L. (2000). Capital-skill complementarity and inequality: A Macroeconomic analysis. Econometrica, 68(5), 1029–1053.

Lee, D. Y., & Tsang, E. W. (2001). The effects of entrepreneurial personality, background and network activities on venture growth. Journal of Management Studies, 38(4), 583–602.

Masurel, E., Nijkamp, P., & Vindigni, G. (2004). Breeding places for ethnic entrepreneurs: A comparative marketing approach. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 16(1), 77–86.

Mehmetoglu, M., & Jakobsen, G. (2016). Applied statistics Using Stata: A Guide for the Social Sciences. Sage Publications.

Milliken, F., & Martins, J. L. (1996). Searching for common threads: Understanding the multiple effects of diversity in organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, 21(2), 402–433.

Moyo, I. (2014). A case study of lack African immigrant entrepreneurship in inner City Johannesburg using the mixed embeddedness approach. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 12(3), 250–273.

Nikolova, E., & Simroth, D. (2013). Does cultural diversity help or hinder entrepreneurship? Evidence from Eastern Europe and Central Asia. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Working Paper 158.

Ottaviano, G., & Peri, G. (2006). The economic value of cultural diversity: Evidence from US cities. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(1), 9–44.

Portes, A., Haller, W. G., & Guarnizo, L. E. (2002). Transnational entrepreneurs: An alternative form of immigrant economic adaptation. American Sociological Review, 67(Apr), 278–298.

Ram, M., Sanghera, B., Abbas, T., Barlow, G., & Jones, T. (2010). Ethnic Minority Business in Comparative Perspective: The Case of the Independent Restaurant Sector. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 26(3), 495–510.

Reynolds, P., Bosma, N., Autio, E., Hunt, S., De Bono, N., Servais, I., & Lopez-Garcia, P. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: Data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 205–231.

Roback, J. (1982). Wages, rents, and the quality of life. Journal of Political Economy, 90(60), 1257–1278.

Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Hardy, D. (2015). Cultural diversity and entrepreneurship in England and Wales. Environment and Planning A, 47(2), 392–411.

Runyan, R. C., Huddleston, P., & Swinney, J. (2006). Entrepreneurial orientation and social capital as small firm strategies: A study of gender differences from a resource-based view. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 2(4), 455–477.

Saxena, A. (2014). Workforce Diversity: A Key to Improve Productivity. Procedia Economics and Finance, 11, 76–85.

Smith, R., & Zoega, G. (2009). Keynes, investment, unemployment and expectations. International Review of Applied Economics, 23(4), 427–444.

Sobel, R., Dutta, N., & Roy, S. (2010). Does cultural diversity increase the rate of entrepreneurship? Review of Austrian Economics, 15(3), 269–286.

Somashekhar, M. (2019). Ethnic economies in the age of retail chains: Comparing the presence of chain-affiliated and independently owned ethnic restaurants in ethnic neighbourhoods. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(13), 2407–2429.

Szkudlarek, B., & Wu, S. X. (2018). The culturally contingent meaning of entrepreneurship: Mixed embeddedness and co-ethnic ties. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development. Routledge, 30(5–6), 585–611.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (2004). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Politcal Psychology, 276–293.

Vandor, P., & Franke, N. (2006). See Paris and… found a business? The impact of cross-cultural experience on opportunity recognition capabilities. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(4), 388–407.

Volery, T. (2007). Ethnic entrepreneurship: A theoretical framework. In: L. P. Dana (ed.) Handbook of Research on Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship: A Co-evolutionary View on Resource Management. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Yinger, J. M. (1985). Ethnicity. Annual Review of Sociology, 11(1), 151–180.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RGR is the only contributor of this article. She assembled, analyzed all data as well as wrotethe entire manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gutiérrez-Romero, R. Businesses create more jobs in countries with higher share of immigrants because of skill complementarity. J Glob Entrepr Res 13, 2 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40497-023-00345-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40497-023-00345-5