Abstract

This systematic literature review examines the varied presentations of depression in depressed autistic individuals, including symptoms beyond DSM-5-TR criteria. A search of five databases (updated February 2024) identified 24 studies, encompassing 243 autistic individuals. Study quality varied, assessed using QuADS. The review was pre-registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022355322). Results were synthesised based on DSM-5-TR criteria and additional presentations, including who reported them. Findings showed 91.66% of studies reported presentations beyond DSM-5-TR criteria. Additionally, some DSM-5-TR symptoms may present differently in autistic individuals. Variations in depressive signs were noted across self-reports, informant-reports, interviews, and questionnaires. Clarifying whether these additional presentations are autism-specific, arise from the intersection of autism and depression, or manifestations of a depressive disorder is necessary for refining diagnostic tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autistic individuals have a lifetime prevalence of depressive disorders that is four times higher than that of non-autistic individuals (Hudson et al., 2019). For autistic individuals, the impact of depression can be profound; depression is associated with a lower quality of life (Oakley et al., 2021), increased prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempts (Cassidy et al., 2022), loneliness, and lower employment (Hedley et al., 2018). Despite the high prevalence and significant impact, depression may be under- or misdiagnosed in autistic individuals (Chandrasekhar & Sikich, 2015). One possible reason for this is an incomplete understanding of how depression presents in this group, which may include symptoms or signs that differ from non-autistic individuals. This review builds upon the scoping review by Angel et al. (2023). While Angel et al. explored depression symptoms in autistic individuals in general, including those with and without a depression diagnosis (i.e. symptoms may not be due to a clinical diagnosis per se), this review focuses specifically on autistic individuals who have been diagnosed with depression. By focusing on those with confirmed depression, it is possible to report depressive symptoms in formal diagnostic criteria, and then also explore potential additional signs of depression that may be experienced by autistic individuals who have been diagnosed as depressed. This approach is necessary to begin to address the gaps in understanding depressive presentations and subsequently improve diagnostic accuracy.

Depression Diagnosis in Autistic People

Depressive disorders, including Major Depressive Disorder, Persistent Depressive Disorder, and Seasonal Affective Disorder, are characterised by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a lack of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities. Depressive disorders are typically diagnosed through clinical interviews and standardised diagnostic tools. For example, Major Depressive Disorder diagnosis may be informed by measures such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001), the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), and the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996). These tools are generally used alongside clinical judgement informed by classification systems, commonly the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text rev.; DSM-5-TR; APA, 2022). Using these processes, the prevalence rate for depressive disorders in autistic individuals is estimated to be significantly higher than in the general population, at 23% (Hollocks et al., 2019), relative to 4.4% globally in the general population (WHO, 2017). Growing research into depression in autistic individuals indicates depression may be either overlooked or incorrectly diagnosed in autistic individuals due to overlapping depressive symptoms with autism characteristics, diagnostic overshadowing, and a lack of tailored assessment tools (Cassidy et al., 2018).

Depression symptoms sharing similarities with autistic characteristics can complicate differential diagnosis. For example, avoidance of social situations, differences or reduced range of emotional expression, and difficulties with eating or sleeping may be observed in both conditions (APA, 2022). Further, diagnostic overshadowing can occur, where depressive symptoms in autistic individuals are mistakenly attributed to autism itself rather than being recognised as signs of a co-occurring depressive disorder (Hollocks et al., 2019; Oakley et al., 2021). Identifying and differentiating depression symptoms from autism characteristics becomes further challenging in the presence of specific co-occurring conditions, including intellectual disability which is seen in up to 33% of autistic individuals and varying communication styles (e.g., use/non-use of verbal speech) (Maenner et al., 2020; Vogindroukas et al., 2022). Cognitive and verbal communication use/understanding can influence how depression is presented and reported, as reliance on behavioural observations may overlook the cognitive and emotional aspects of depression in those with difficulties communicating their emotions and thought processes (Long et al., 2000). Additionally, current depression inventories, designed and developed for non-autistic populations, may not adequately account for the literal interpretation styles common among autistic individuals, potentially leading to inaccuracies in capturing their experiences (Cassidy et al., 2021). Alexithymia, a common characteristic in approximately 50% of the autistic population, can impact self-reporting of emotional experiences, making it difficult for some autistic people to articulate their internal states (Kinnaird et al., 2019). These differences in how autistic people experience and interact with the world may result in a wider range of depression presentations compared to non-autistic people. Therefore, a thorough and careful approach to depression diagnosis is needed that considers the influence of autism characteristics and the potential range of depressive presentations.

Depression may present differently in autistic individuals. Similar to that reported for anxiety (Adams et al., 2019; Kerns et al., 2014), depression presentations in autistic individuals may encompass both well-described symptom clusters (e.g., DSM-5-TR) and differing (“autism-distinct”) expressions of depression (Oakley et al., 2021; Rhodes et al., 2023). For instance, an increase in restricted and repetitive behaviours such as dietary restrictions or stimming may be examples of autism-distinct expressions of depression in autistic people (Rhodes et al., 2023). As such, a detailed understanding of the presentation of depression in autistic people is needed to improve diagnostic accuracy and, consequently, treatment effectiveness. One way to do this is to explore the presentations reported in autistic people who have a confirmed diagnosis of depression and how their reported symptoms of depression do or do not align with established criteria for depression. While this will not result in an exhaustive list of potentially autism-distinct signs of depression (as there may be signs of depression that are not interpreted as such, and therefore, the person is not diagnosed), it provides a first step to identifying autism-distinct signs in autistic people who have confirmed depression.

Building on the findings from a systematic review by Stewart et al. (2006), a recent scoping review by Angel et al. (2023) examined how depressive symptoms present in autistic individuals across various ages and intellectual abilities. Angel et al. included studies that investigated depressive presentations in both diagnosed and undiagnosed autistic individuals. The review found that many depressive symptoms common in the non-autistic population, such as anhedonia, fatigue, feelings of failure, and changes in sleep and eating patterns, also appear in autistic individuals. However, compared to non-autistic adults, autistic adults were less likely to indicate suicidal thoughts or feelings or difficulties with concentration. These depressive symptoms were often expressed through behavioural changes rather than verbally. For example, depressed mood in autistic individuals was usually inferred from nonverbal cues, including a sad demeanour, rather than being directly articulated. The review also noted that autistic individuals may exhibit additional or alternative indicators of depression like increased autistic characteristics, developmental regression, and self-injurious behaviours. This review extends this previous work by systematically documenting the presentations of depression in autistic individuals with diagnoses and exploring these with DSM-5-TR criteria for depressive disorders. By focusing on autistic individuals diagnosed with depression, variability is reduced, and there can be increased certainty regarding possible additional signs of depression reported in this population, which can then, in turn, be used to improve diagnostic criteria and treatment practices.

Aims and Focus of this Review

This review focuses on autistic individuals diagnosed with depression. We aim to identify depressive presentations in depressed autistic individuals and explore which elements of their reported presentation align with, or differ from, the DSM-5-TR criteria for depressive disorders. Across studies, we aim to:

-

1.

Identify and assess the quality of existing research that reports on depression presentations in autistic individuals diagnosed with depression according to clinical criteria.

-

2.

Synthesise and compare the presentations of depression reported by autistic individuals and their informants (parents, professionals) against the DSM-5-TR criteria for depression, identifying those presentations that align, and those that do not align, with the DSM-5-TR.

-

3.

Explore potential similarities and differences between how autistic individuals self-report their depressive presentations and how informants perceive these presentations.

-

4.

Summarise the non-DSM-5-TR depression presentations reported by autistic individuals and informants to document presentations that extend beyond the DSM-5-TR criteria.

Method

This systematic review was pre-registered with PROSPERO, registration number CRD42022355322. The review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). In this review, the term 'depression' is used to include the unipolar depressive spectrum, including major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and persistent depressive disorder. Consistent with the DSM-5-TR classification and their clinical features, bipolar disorders, which encompass Bipolar I, Bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder and are characterised by manic/hypomanic episodes, are excluded from this review. Additionally, ‘symptoms of depression’ refer to presentations that align with the DSM-5-TR criteria for depressive disorders, while ‘other indicators of depression’ include presentations reported that do not align with the DSM-5-TR criteria but may still be indicative of depressive experiences. The term 'presentations of depression' will be used to refer to both symptoms and other presentations of depression collectively.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria stated that (1) participants had a current formal diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder meeting the DSM-5-TR criteria, or any Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD) diagnosis from earlier DSM editions, including Autistic Disorder, Asperger's Disorder, or PDD-Not Otherwise Specified, or identify themselves as autistic; (2) participants have a depressive disorder diagnosis, which was predefined as having a formal clinical diagnosis, meeting depression criteria based on cut-off scores from recognised depression inventories, or a self-reported diagnosis aligned with symptom checklists in clinical research; (3) the article provides details on the presentations of depression in participants. For qualitative studies, this was defined as direct quotes that described presentations of depression by autistic individuals, caregivers, or professionals and were detailed and supplemented with an interpretive analysis from the authors. For quantitative studies, this required item-level reporting of measures/depression inventory scores for the depressed group; (4) the study is published in a peer-reviewed journal article published since 1994, coinciding with the revised autism diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), ensuring consistency in included participants and diagnostic terminology. The review considered studies in all languages and across all age groups.

Exclusion criteria were (1) participants have a history of bipolar disorder, including Bipolar I, Bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder; (2) depression presentations not reported separately from other conditions unless the specific impact of depression was clearly defined; (3) secondary analysis of primary research, such as literature reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, commentary articles; and (4) opinion pieces, book chapters, and dissertations. These manuscript types (3 and 4) were excluded to maintain a focus on primary research findings from peer-reviewed sources.

Search Strategy

Five electronic databases (PsycINFO, Embase, Scopus, Science Direct, and PubMed) were searched on 16 August 2022, with an updated search on 22 February 2024. In both searches, filters were applied to include only peer-reviewed journal articles published between 1994 and the search date. The searches were conducted using the following keyword structure: (autis* OR ASD OR ASC OR Asperger* OR “pervasive developmental disorder*” OR PDD-NOS) AND (depress* OR “Mood disorder*” OR “Affective disorder*” OR dysthym* OR “low mood “) AND (behav* OR observation* OR present* OR symptom* OR charact* OR pathol* OR manifest* OR indicat* OR phenomenol* OR Feature* OR appear* OR signs). Proximity operators and keyword structure were tailored to each database's specifications to ensure the search was conducted within titles and abstracts.

Study Selection Process

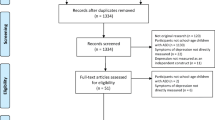

The initial searches identified 11,097 articles (refer to Fig. 1). After automatically removing duplicates in Covidence, 6,921 articles remained for title and abstract screening. The primary reviewer screened titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a random sample of 20% was independently reviewed by a second reviewer, as per recommended practices for large-scale limited resource reviews (Popay et al., 2006). Cohen’s Kappa indicated high inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.94) (McHugh, 2012). Discrepancies were discussed with both reviewers to reach a consensus.

Any article deemed potentially relevant by either reviewer underwent a full-text review. Of the 137 articles assessed independently, both reviewers agreed on the inclusion of 97% (133/137). Disagreements on four articles were resolved through discussion, resulting in the inclusion of 22 articles. Reference lists of included papers and previous systematic reviews on autism and depression were screened for potential articles by checking the titles in the reference lists for wording indicative of meeting the inclusion criteria. Through this process, three articles were identified and included in the review. These were included after confirming, through full-text review, that they met the inclusion criteria, which were missed in the initial search due to their not mentioning depressive presentations in their titles or abstracts. For example, one abstract focused on validating a screening tool without directly mentioning depressive presentations (Arnold et al., 2020). Overall, 25 articles met the inclusion criteria for this review, but this was reduced to 24 after one article (Perry et al., 2001), was excluded during the data extraction phase because the diagnosis of depression was not sufficiently clear, making it difficult to determine if the presentations were due to depression or another condition.

Data Extraction

Two researchers independently extracted data in an Excel spreadsheet, with a high percentage agreement of 98% (329/336). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, achieving consensus in each instance. Extracted details included authors, publication year, study country, design, sample characteristics (number, age, gender, cognitive ability), autism and depression assessment details (diagnosis, criteria), depression presentations (self or informant reported, symptoms descriptions,), and depression measures (name, item scores). Depression presentations were only coded if they were reported as occurring or as a change from the individual's baseline during the depressive disorder.

The coding framework for this review was systematically developed to categorise depression presentations in autistic individuals reported in case and qualitative studies extracted data, adhering to directed content analysis as outlined by Hsieh and Shannon (2005). The first stage involved creating codes from DSM-5-TR depression descriptors for initial coding categories, including depressed mood, diminished interest, appetite and weight changes, sleep disturbances, psychomotor issues, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, concentration difficulties, and suicidal thoughts. In the second stage, operational definitions for these codes were then developed based on the criteria and descriptions in the DSM-5-TR. For example, mentions of sadness or emptiness were coded under ‘Depressed Mood’.

The third stage involved applying these codes to the descriptions in the data. New codes were developed (inductively) for content that did not fit existing codes. Inductive coding began with thoroughly reading the data and constructing patterns and themes, which were then labelled with codes. The lead author continuously refined and adjusted these codes as more data were reviewed, ensuring they accurately represented participants' experiences. This iterative process provided codes to describe descriptions of depression that could not be categorised under the predefined DSM-5-TR codes. A final codebook (codes, definitions, examples) is available on Open Science Framework for transparency and replicability:https://osf.io/x4p8t/?view_only=db13513119eb419382b7f819a5424f1f

For quantitative data synthesis, using a systematic method to extract data across all study designs and the multiple measures used was deemed important. To allow for a narrative comparison with previous reviews on depression in autistic individuals, we adopted an approach similar to Angel et al. (2023), who appeared to report three to five items from depression inventory scores. It was decided a priori to extract the top three depression presentations from each study, selecting them based on the highest frequency or mean scores. Focusing on these top three aims to highlight the most commonly reported symptoms. When multiple items scored equally, additional symptoms were included. This identification was straightforward for measures such as the PHQ-9, where each item aligns with the DSM-5-TR criteria for depression. However, for scales such as the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI-2; Kovacs et al., 2010), items were grouped into subscales that align with the DSM-5-TR criteria for depression. For instance, items related to " low mood" were combined, and their scores were averaged to represent depressed mood. The top three categories were then selected based on the combined scores. All results were systematically tabulated. The two reviewers agreed on 91% of codes (153/168), with 15 discrepancies due to either unclear classifications of autistic characteristics and obsessive–compulsive behaviours (three times) or ambiguously described depression presentations (12 times), resolved through discussion to consensus.

Quality Appraisal

The included studies were evaluated using the Quality Assessment for Diverse Studies (QuADS), as described by Harrison et al. (2021). This tool assesses 13 criteria (e.g., clarity of research aims, rationale for data tools) on a 0–3 scale, with higher scores indicating more detailed reporting. A score of 3 means that a criterion is fully met. The tool has demonstrated to show adequate/good inter-rater reliability and content and face validity (Harrison et al., 2021). Two researchers completed the quality assessment of each included article. Cohen’s Kappa indicated near-perfect inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.898). Both reviews discussed any discrepancies and reached a consensus. The overall scores reflect each study's reporting and methodological quality (quality findings are below).

Results

The review identified 24 articles, all in English, including 28 case studies (reported in 16 articles; see Table 1), two qualitative studies, and six group-based quantitative studies (summarised in Table 2). Although the number of studies on depression in autistic people showed some fluctuation from 1994 to 2019 (15 articles), there appears to be an increase in the last four years (9 articles). Earlier publications were predominantly case studies (11/15 articles before 2020). Since 2020, articles still feature case studies (5/9 articles) but now include two qualitative studies.

Quality of Reporting of Included Studies Using QuADS

The QuADS, with 13 items and a total score of 39, was used to assess the quality of reporting of the included studies. Scores ranged from 3 to 37, averaging 17.21 (SD = 10.77). None of the studies met all QuADS criteria. Case studies scored lower (M = 11.06) than quantitative and qualitative studies (M = 29.5). Theoretical or conceptual underpinning had the highest average score (M = 2.42), while stakeholder consideration was the lowest (M = 0.21), indicating limited community engagement. Only three studies demonstrated community involvement: Rhodes et al. (2023) included community perspectives, Schwartzman et al. (2022) integrated an autistic researcher, and Zupanič et al. (2021) incorporated feedback from an autistic participant and obtained their approval for the final manuscript. The total scores for each study are detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 describes 28 case studies on autistic people from the UK (n = 6), the US (n = 3), and Japan (n = 2), with one each from Australia, Italy, France, Slovenia, and the Netherlands. Most lead authors were from psychiatry (cases n = 25). Table 2 presents two qualitative studies, both reporting on semi-structured interviews from the UK and six comparative quantitative studies, mainly from the US (k = 4) and one from Australia and Norway. Sample sizes ranged from 1 to 137 autistic participants with a history of depression (M = 12.45; SD = 29.81). Three quantitative studies compared depression presentations between depressed and non-depressed autistic individuals, and three compared depressed autistic individuals and depressed non-autistic individuals. Arnold et al. (2020) included autistic and non-autistic samples of both depressed and nondepressed individuals.

Participant Demographics

Across the 24 studies, 243 autistic individuals with depression were represented. Data on participant gender were only available for 125 individuals, reflecting partial reporting across studies. Among these 125 individuals, 70% were male, 29% female, and one trans-male. For the remaining studies, gender data was not reported or provided for the full sample without distinguishing between depression diagnoses. The overall age range of the participants ranged from 6 to 80 years. Demographics by study type are outlined below.

In the 16 case studies, 28 individual people, ages ranging from 6 to 60 years, were described. For the case studies, children and adolescents (10 participants) had an average age of 14.27 years (SD = 3.80), and adults (18 participants ≥ 18 years) averaged 28.94 years (SD = 11.32). Intelligence quotient (IQ) scores were reported for 20/28 people, with 13 indicating an intellectual disability. For qualitative studies, one study focused on adults aged 19–51 (M = 31.75), and the other on youths aged 9–18 (M = 15.05). Both studies excluded participants with an intellectual disability. In the quantitative studies, 226 participants were aged 15 to 80 years. Among them, the IQ score of 68 participants was explicitly reported, with 26.47% of these participants identified as having an intellectual disability.

Depression Presentations in Autistic Individuals

Table 1 categorises the depressive symptoms observed in 28 autistic individuals from case studies according to the DSM-5-TR criteria for depression. Table 2 summarises findings from qualitative and quantitative studies, aligning them with the DSM-5-TR criteria for depression. Table 3 provides a comprehensive summary of depression symptoms across all data sources. In the self-report and informant report sections, the diagnostic criteria for depression are presented in the order outlined in the DSM-5-TR, with a description of each symptom's presentation. Additionally, a separate section highlights depression presentations that do not align with the DSM-5-TR criteria.

Source of Data on Depression Presentations

Self-report data on depression presentations was included in 7/28 people in case studies, two of whom also described data from other informants. These cases exclusively involved autistic individuals without intellectual disabilities. Informant-reported data, primarily from parents or caregivers, with some from clinical teams, was used in the remaining 21 cases involving participants reported to have an intellectual disability. Clinical observations and interpretations were also included in all case studies. The two qualitative studies utilised self-reported data, with additional parent input in the study involving children. In the quantitative studies, informant-reported data was used for participants (n = 29) with and without an intellectual disability. Participants without intellectual disabilities (n = 197) provided self-reported data.

Self-reported Symptoms that Align with DSM-5 Criteria for Depression

In the reviewed studies, autistic individuals often described experiencing depressive symptoms as internal changes that deviated from their typical emotional states. Depressed mood was the most frequent symptom identified and was expressed in a variety of ways ranging from explicit statements of sadness and episodes of crying to more metaphorical language, such as comparing their emotional state to 'the underworld’ (Takaoka & Takata, 2007, p.964). One autistic adult used a depression questionnaire to communicate their feelings (Özgen & van den Brink, 2021), while an autistic child articulated a reluctance to cry despite feeling sad, noting, “I'm not really a person to cry” (p.4), a sentiment he reflected as a broader trend among autistic individuals (Rhodes et al., 2023).

Anhedonia, or lack of enjoyment in previously enjoyable activities was expressed by children as diminished pleasure, with statements like, "Sometimes I feel like I can't really enjoy things that much" and "you kind of forget what it is to enjoy things" (Rhodes et al., 2023, p.6). Some individuals described engaging more intensely in activities as a coping mechanism. They maintained or even increased their involvement in these activities not out of actual enjoyment but as a way to alleviate depressive distress (Jordan et al., 2021; Rhodes et al., 2023). Individuals reported changes in appetite or sleep as a reduction. Psychomotor activity was described as an “oppressed feeling…an uncontrolled force pulling down “ (p.965), leading to slower movements (Takaoka & Takata, 2007). Descriptions of concentration difficulties varied, for example, difficulties with thinking or concentration or feeling like being trapped in a box (Özgen & van den Brink, 2021), while children described an influx of thoughts and the inability to channel their focus, making concentrating impossible (Rhodes et al., 2023). Feelings of worthlessness and guilt were articulated by autistic adults as negative and critical self-talk, with descriptions such as “a failed person” and “a loser” (Jordan et al., 2021, p.1687). Children also described these feelings, impacting their social interaction as one child described, “because of the guilt and stuff that comes with depression, there’s a level of you that doesn’t want to see your own friends because they might not think you’re the same person” (Rhodes et al., 2023, p.4). Although suicidal ideations were reported, no specific details were provided.

Informant Reported Symptoms that Align with DSM-5 Criteria for Depression

Informant reports, primarily from caregivers and health professionals, suggested that changes in mood or behaviour are pivotal observed indicators of depression in autistic individuals. Depressed mood, the most observed perceived symptom, was described as diminished facial expressions, reduced smiling, and signs of misery or crying. Some children were reported to express sadness directly, while others exhibited persistent irritability, considered by the article’s authors as an alternative presentation of depressed mood, aligning with the DSM-5-TR criteria for diagnosing depression in youths (Rhodes et al., 2023).

Informants described anhedonia as a noticeable decrease in engagement and enjoyment in activities previously found pleasurable. For instance, one parent described their child's diminished enjoyment by telling her, "Mum, I know I'm supposed to have enjoyed that… but I felt I couldn't enjoy it" (Rhodes et al., 2023, p.6). Changes in appetite were also noted, with nearly all individuals experiencing a decrease, often accompanied by weight loss; however, one individual noted an increase in appetite and subsequent weight gain. Sleep disturbances included insomnia and disrupted sleep patterns. However, due to the bidirectional nature of depression tools, such as the PHQ-9, which includes the item “poor appetite and overeating”, it was challenging to categorise some reports of changes in appetite and sleep patterns as either increases or decreases.

In the reported cases of psychomotor changes, 53.8% involved psychomotor retardation, characterised by slower body movements, muted speech, and reduced spontaneity. The remaining 46.2% displayed signs of agitation, such as constant moving or chewing fingers. Concentration difficulties were often inferred from declines in academic or occupational performance. Parents described that their children were distracted by overwhelming thoughts, which hindered their ability to engage in activities like reading or artwork. One parent noted, “he almost can’t engage with what’s going on in the world” (Rhodes et al., 2023, p.6). Although informants noted feelings of worthlessness or guilt, lethargy, or a general loss of energy, specific details were often lacking.

Suicidal ideation among autistic individuals were described in some case studies, a number of whom had co-occurring intellectual disabilities. The clinician of a 6-year-old child with moderate intellectual disability spoke about the child's shared suicidal thoughts using third-person references, stating, “I want to kill…want a different Julia” (Pollard & Prendergast, 2004, p.487). Similarly, a clinician of a 19-year-old with mild intellectual disability shared that the child had made multiple suicide attempts and expressed a wish to “die and go to heaven” (Wachtel et al., 2010, p.71). These reports are among the few explicitly described instances of depression symptoms by autistic individuals with intellectual disabilities in this review.

The Focus of Descriptions of Depressive Symptoms in Self-reports and Informant Observations

None of the included studies compared self-reported and informant-reported presentations of depression. Self-reports often reported internal emotional states, such as depressed mood, feelings of worthlessness, guilt, and concentration difficulties, more frequently than external presentations, including sleep and appetite disturbances, across case, quantitative, and qualitative studies. In these self-reports, concentration difficulties were detailed through personal experiences, such as an influx of thoughts, contrasting with informant reports that typically noted changes in academic or occupational performance. Depressed mood, a recurrent theme in self-report case studies, was sometimes expressed directly as well as metaphorically. This differs from informant reports, which focus more on observable behavioural changes, such as altered facial expressions.

Anhedonia was reported in both self and informant reports, yet the description varied. Autistic individuals described a decrease in internal enjoyment, occasionally alongside sustained or increased engagement in special interests. In contrast, informants tended to observe changes in behaviour, like reduced activity levels. Appetite changes, sleep disturbances, and fatigue were acknowledged by both but with differing frequencies; appetite and sleep issues were more commonly reported by informants, whereas self-reports more frequently reported fatigue. Notably, psychomotor changes, especially slower body movements, occurred in informant reports but were rarely mentioned in self-reports. Suicidal ideations were reported in case and quantitative studies. Among autistic individuals with intellectual disabilities, descriptions of suicidal thoughts represented the only instances where these individuals were reported as expressing symptoms of depression themselves.

Depression Indicators Reported that do not Align with DSM-5 Criteria for Depression

In addition to the nine DSM-5-TR symptoms of depression noted above, 91.66% of the articles reviewed reported at least one additional presentation concurrent with depression. As these cannot be described as symptoms (as per the DSM-5-TR), they are hereafter termed ‘other indicators of depression’ (see Table 4). Increases or changes in autistic characteristics, typically described using clinical terminology, are the most frequently reported. For example, increased stereotypic and ritualistic behaviours were noted, with some reports specifically mentioning behaviours such as “stimming more” (Rhodes et al., 2023) and perseveration (Ozinci et al., 2012). Parents of autistic children observed increased restrictive and repetitive behaviours, particularly in eating habits. They observed their children consistently preferred the same foods and showed reluctance to try new ones; as mentioned, “he gets more restrictive if he feels sadder” (Rhodes et al., 2023, p.4). Additionally, one child’s existing special interest changed to a depressive nature, as he became convinced he would fall into the "dark hole of space"(p.499) and die, which the authors described as a shift in the nature of his special interests associated with the onset of depression (Ghaziuddin et al., 1995).

A broad range of anxiety symptoms were reported to occur alongside symptoms of depression. This included anxious distress, stress-related phobias, and a preoccupation with future problems rather than present concerns, either as an increase to existing anxiety or a new onset. In autistic children, anxiety frequently co-occurred with depression, profoundly affecting daily activities, sleep, and social interactions. Children and their parents described anxiety as both a root cause and a complicating factor for depression, exacerbating feelings of pessimism and negatively impacting emotional regulation and engagement in enjoyable activities (Rhodes et al., 2023). Obsessive or compulsive tendencies were reported as either new onset or increased, as distinct yet concurrent presentations during episodes of depression. In some cases, these tendencies intensified existing obsessive behaviours, complicating the distinction from autistic characteristics (Hutton et al., 2008). Irritability was reported among adults and youths, both with and without intellectual disabilities. Parents particularly noted the impact of irritability, stating that “when he’s irritated when he’s depressed, it adds an extra layer of depression and upset” (Rhodes et al., 2023, p.6).

Heightened social withdrawal was reported as a behaviour distinct from autistic behaviours (Jordan et al., 2021; Rhodes et al., 2023). This withdrawal often stemmed from a desire to mask depressive symptoms due to fears of judgment or misunderstanding. Both autistic adults and children were reported to be acutely aware of their changing behaviours and often chose withdrawal as a strategy to conceal their altered state. Masking depression symptoms was taxing, leading to increased fatigue and potentially worsening the depression. This concealment often resulted in further isolation, intensifying feelings of loneliness and aggravating the depressive state. Several parents highlighted sensory overload as a significant factor in their child’s withdrawal (Rhodes et al., 2023).

Externalising behaviours, such as aggression (e.g., punching others in the face or objects) and disruptiveness, were reported during depressive episodes. Parents observed more frequent mood swings and increased violence; one noted, “he was very violent towards his younger sister”, while another child described their own behaviour: “I just feel like kicking off and I don’t know, sometimes I punch walls” (Rhodes et al., 2023, p.6). Self-injurious behaviour (SIB) was also reported among youths and adults with and without an intellectual disability. Reported behaviours included headbanging, hand-to-body hitting, self-biting, and self-gagging. One child contemplated SIB, “I even think about doing something like spraying air freshener in my eyes” (Rhodes et al., 2023, p.6). Additional presentations concurrent with depression also included developmental regression, which presented as a range of behaviours such as incontinence in previously continent individuals, reduced ability to use Makaton signing, needing prompts for previously acquired skills, and speech regression. Various somatic symptoms were reported during depressive episodes as well, including constipation, headaches, catatonia, motor tics, and, in cases of severe depression, auditory hallucinations.

Discussion

This systematic review reports on depression presentations in depressed autistic individuals, including possible indicators of depression outside of those described in the DSM-5-TR criteria for depressive disorders. The studies included in this review report a broad spectrum of depressive presentations that align with, and deviate from, established criteria for depressive disorders. Variations appear in the signs of depression reported via self-reports and informant reports, as well as between assessment methods (e.g., interviews, questionnaires). While the review identified other indicators of depression, their nature is unclear; whether they originate from autistic characteristics, inherent to autism intersecting with depression, or direct manifestations of a depressive disorder highlights the need to clarify these presentations. Resolving these ambiguities is essential before we can develop or refine diagnostic tools that accurately capture the depressive experiences of autistic individuals.

Evaluating Reporting Quality and Ethical Considerations of the Included Research

There were limitations in the reporting quality of the included studies, including limited engagement of community stakeholders, incomplete descriptions of consent procedures, a variety and lack of appropriate assessment measures, and small sample sizes. Engagement of community stakeholders is needed to ensure that research is ethically grounded, reflects the lived experiences of autistic individuals, and drives meaningful, participatory change in policies and practices (Poulsen et al., 2022). Obtaining assent from individuals who may not fully comprehend the implications or ensuring informed consent where feasible is necessary to protect participant rights and autonomy (Kadam, 2017). Additionally, the use of assessment measures often not validated for the autistic population (Cassidy et al., 2018), combined with small sample sizes, complicates the interpretation of symptoms and affects the consistency of research findings and their generalisability across the autistic population. Current research often neglects to differentiate between depressed and non-depressed individuals and underrepresents adults and those with intellectual disabilities (Ozinci et al., 2012; Schwartzman & Bonner, 2023).

Depression Symptoms Reported in Autistic Individuals

The most frequently reported depressive symptoms across all sources were depressed mood, followed by anhedonia, changes in sleep, psychomotor changes, changes in appetite, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, suicidal ideations, and difficulties concentrating. However, there were noticeable differences between symptoms reported by self and informant reports. The symptoms described in self-reports compared to informant reports had different foci; self-reports tended to report internal emotional states, whereas informant reports tended to describe observable behaviours. Autistic individuals without an intellectual disability often describe internal emotional states associated with depression, such as depressed mood, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, anhedonia, suicidal ideations and difficulties with concentration. In contrast, informant reports (i.e., parents, caregivers, practitioners), mostly of autistic individuals with intellectual disability, focus on observable changes in behaviour, mood, and physical states, like facial expressions, activity levels, sleep patterns, and appetite. Research indicates that autistic individuals tend to report their internal states, while parents are more likely to report observable behaviours (Bitsika & Sharpley, 2015; Gotham et al., 2015). Gotham et al. (2015) found significant discrepancies in the CDI-P Emotional scale (Kovacs et al., 2010), indicating that parents and children often perceive emotional symptoms of depression differently. Such differing foci of symptom reporting have also been observed in anxiety and other mental health conditions (Sandercock et al., 2020; Storch et al., 2012).

None of the included studies compared self-reported and informant-reported presentations of depression; however, a meta-analysis by Hudson et al. (2019) found significant variations in depression prevalence rates between self-reports (25.9%) and informant reports (10.4%). Such discrepancy suggests that while informant reports may misinterpret the internal emotional states of autistic individuals, self-reports may also present challenges, including limited introspective ability, varied interpretations of questions, response bias, and the suitability of response scales (Cassidy et al., 2018, 2021). Differences in item-level reports between self-reports and informant reports may arise from differences in communication styles and the interpretation of depressive symptoms as variations in autistic behaviour rather than as indicators of depression. For instance, autistic individuals' experiences of fatigue or lack of energy may be overlooked or misinterpreted by informants as autistic behaviour, such as preferencing alone time over social activities. Consequently, while observable indicators can help identify potential signs of depression, they may not fully capture the individual's experience. Recognising autistic individuals' communication styles and experiences is necessary to avoid misdiagnosis, making multi-informant reports necessary to fully understand an individual’s depressive experience by considering both internal states and observable behaviours.

The varied expressions of DSM-5-TR criteria symptoms among autistic individuals further highlight the need for a broader diagnostic approach. For instance, depressed mood and anhedonia were frequently reported by autistic individuals, though their expression often varied. While Angel et al. (2023) findings suggested that autistic individuals rarely express depressed mood outwardly, studies in this review provided examples of outward expression of depressed mood through both self-reported and informant-reported. However, some autistic people may express this differently from non-autistic expectations, such as metaphorically. Experiences like suicidal ideation were articulated by some autistic individuals, including those with intellectual disability, and are more frequently documented in case studies than in other study designs (Pollard & Prendergast, 2004; Skinner et al., 2005; Wachtel et al., 2010). The presence of suicidal thoughts among self-reported autistic individuals, reported as the fourth most common symptom and as frequently as anhedonia, differs from the findings by Angel et al. (2023), who reported a lesser likelihood of such expressions, particularly in adults. These expressions, at times, conveyed through figurative language, challenge prevailing assumptions about the expressive capabilities of autistic individuals and those with intellectual disabilities. Additionally, anhedonia presented uniquely in some autistic individuals who maintain activity engagement despite experiencing diminished pleasure, suggesting a coping strategy akin to escapism from depressive states. Such behaviour might also be influenced by a need for consistency and routine, providing structure and predictability that could inadvertently help mitigate depressive symptoms (Goldfarb et al., 2021). Such diverse presentations highlight the need for a comprehensive diagnostic approach beyond solely observable behaviours.

Other Possible Indicators of Depression

Other potential indicators of depression in autistic individuals beyond the DSM-5-TR criteria for depression include increased camouflaging and social withdrawal, heightened autistic characteristics, anxiety, irritability, developmental regression, and externalising and self-injurious behaviours. These indicators often co-occur and interact with one another, further complicating the presentation and assessment of depression. The heightened need for camouflaging and subsequent social withdrawal may lead to increased isolation, which is associated with higher levels of loneliness and depression (Hymas et al., 2022), and diminished peer support, a known protective factor against mood disorders, at least within the general population (Pfeiffer et al., 2011). Concurrently, depression can impact autistic characteristics, such as repetitive behaviours (e.g., stimming), with some individuals unaware of this impact until highlighted by others (Rhodes et al., 2023). Anxiety, which frequently co-occurs with depression, can manifest as an increase or acute onset during depressive episodes, sometimes acting as a precursor or intensifying these episodes (Rhodes et al., 2023). Given the high prevalence of anxiety disorders in this population (Hollocks et al., 2019) and the significant symptom overlap between depression and anxiety (Park et al., 2020), distinguishing between the two poses a considerable challenge, requiring a careful and comprehensive assessment approach.

Irritability, reported alongside depression across various ages and intellectual abilities in autistic individuals in this review, has been previously identified as a distinct and stable dimension that significantly predicts future depression, indicating a strong link throughout life (Vidal-Ribas et al., 2016). This suggests that the DSM-5-TR guidelines (APA, 2022), which associate irritability predominantly with younger demographics, may need to be reconsidered for autistic people. Despite the acknowledged link between irritability and suicidal ideations in the broader depressive disorder population (Jha et al., 2020), the examination of how irritability influences suicidal behaviours in the autistic community remains limited. Given the high incidence of suicidal thoughts and attempts reported among autistic individuals (Cassidy et al., 2022), further research exploring this relationship is urgently needed. Additionally, frequent descriptions of developmental regression and externalising and self-injurious behaviours, also common in studies on anxiety and autism (Adams et al., 2019), highlight the importance of comprehensive screening for these potential indicators, particularly when changes are observed, as these may signal the presence of depression or anxiety.

The varied presentations detailed here highlight the challenges faced by the DSM-5-TR in fully capturing the range of possible indicators of depression experienced by autistic individuals and reflect broader limitations in the current diagnostic criteria when applied across various populations. The DSM-5-TR may not adequately account for the heterogeneity and complexity of depressive presentations, suggesting that its criteria might be too narrow to recognise the unique presentations in both autistic individuals and the general population (Forbes et al., 2023; Newson et al., 2021). To better understand and assess depression, a more inclusive approach aligning with individuals' experiences and acknowledging the significant variability and symptom overlap, particularly in populations like autistic individuals, is necessary.

Influence of Data Collection Methods

The way that data on depressive presentations in autistic individuals is collected may influence what is reported or recorded. Articles that reported upon clinical interviews tended to have detailed descriptions of presentations (e.g., varied expression to diagnostic frameworks) that standardised questionnaires may overlook. However, clinical interviews may introduce interviewer bias and rely on subjective interpretation, potentially affecting the consistency and objectivity of symptom information collected (Allen & Becker, 2019). Questionnaires developed by researchers (Allen & Becker, 2019) are forced-choice questions that provide a standardised method of data collection, reducing the variability introduced by interviewer bias, but may lack the depth and variability in complex emotional states. Moreover, standardised questionnaire assessments developed for non-autistic individuals may use metaphorical language (e.g., DASS (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1996), including “felt down-hearted and blue”), which could be more difficult for some autistic people to understand and less effective in capturing the varied expressions of depression in this population (Cassidy et al., 2018, 2021). These differences in data collection methods, between the detailed yet potentially biased clinical interviews and the standardised but less comprehensive questionnaires, may contribute to the variations observed in the reporting of depressive presentations in autistic people.

Limitations

The methodological rigour of this review, which allowed for the inclusion of studies across all languages and methodologies, strengthens understanding of depression presentations in autistic individuals. The review’s synthesis employed a detailed coding strategy focused on individual baseline deviations, improving the relevance and specificity of the findings. However, this approach might inadvertently overlook certain presentations of depression if they were not explicitly identified as deviations in the reviewed studies. Additionally, a significant portion of the data derives from case studies, which often represent extreme or unique cases and may not fully reflect the broader experiences of the autistic community. Further, challenges in synthesising quantitative data, such as the extraction of the three most prevalent symptoms from each study without differential weighting, may underrepresent critical symptoms like suicidal ideation and behaviours. The review scope did not extend to examining variations in depression presentations across co-occurring conditions such as anxiety and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, nor did it consider gender differences due to the limited details provided in the studies, pointing to a crucial gap in current research.

Implications and Future Research

Accurately diagnosing depression in autistic individuals requires refined clinical and research approaches, given the intersectionality of autistic characteristics and depressive presentations highlighted in this review. Notably, while autistic individuals appear to experience depressive symptoms similar to the non-autistic population (e.g., aligning with the DMS-5-TR criteria), the expression of these symptoms may vary, potentially influencing the relevance of existing depression assessments and questionnaires, an area in need of further research. Future research should aim to distinguish whether the observed other presentations are attributable to autistic characteristics, inherent aspects of being autistic intersecting with core depression symptoms, or direct manifestations of the depressive disorder itself. Clarifying this ambiguity is crucial for tailoring appropriate diagnoses.

Clinicians and researchers should consider how factors like alexithymia and varied communication styles prevalent among autistic individuals can influence the articulation and interpretation of depressive symptoms, potentially introducing interpretation biases further complicated by non-autistic individuals' difficulties in understanding these unique communication methods (Jaswal & Akhtar, 2018; Legault et al., 2019). The observed correlation between autistic characteristics and depression scores (Mayes et al., 2011; Oakley et al., 2021) highlights an overlap that complicates depression diagnosis, potentially leading to elevated inventory scores absent of clinical depression. Existing resources like "Know Your Normal" (Crane et al., 2017) could be expanded upon, with research focusing on developing clearer guidelines for comparing mental health symptoms against personal norms. Most depression assessments lack such guidance, which may undermine diagnostic accuracy for autistic individuals struggling to differentiate between baseline autistic characteristics and new or exacerbated symptoms indicating a potential mental health condition. The findings emphasise the urgent need for diagnostic tools tailored to autistic experiences. Until such advancements, providing guidance on interpreting measures designed for the non-autistic population is essential to improve diagnostic accuracy, which is essential for identifying and addressing the significant rates and impact of depression in autistic people.

Data Availability

The final codebook (codes, definitions, examples) is available on Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/x4p8t/?view_only=db13513119eb419382b7f819a5424f1f. Additional data is available on request by emailing the corresponding author.

References

Adams, D., Young, K., Simpson, K., & Keen, D. (2019). Parent Descriptions of the Presentation and Management of Anxiousness in Children on the Autism Spectrum. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 23(4), 980–992. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318794031

Allen, D.N., & Becker, M.L. (2019). 10 - Clinical interviewing. In G. Goldstein, D. N. Allen, & J. DeLuca (Eds.), Handbook of Psychological Assessment (Fourth Edition) (pp. 307–336). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802203-0.00010-9

Angel, L., Ailey, S. H., Delaney, K. R., & Mohr, L. (2023). Presentation of Depressive Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 45(9), 854–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/01939459231190269

Arnold, S. R. C., Uljarević, M., Hwang, Y. I., Richdale, A. L., Trollor, J. N., & Lawson, L. P. (2020). Brief report: Psychometric properties of the patient health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9) in autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(6), 2217–2225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03947-9

Association, American Psychiatric. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.) (Vol. 4). American psychiatric association Washington, DC.

Association, American Psychiatric. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.) (Fifth edition, text revision. ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., & Brown, G.K. (1996). Beck depression inventory: manual, 2nd edn (BDI-II). In: Boston: Harcourt Brace.

Bitsika, V., & Sharpley, C. F. (2015). Differences in the Prevalence, Severity and Symptom Profiles of Depression in Boys and Adolescents with an Autism Spectrum Disorder versus Normally Developing Controls. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 62(2), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2014.998179

Cassidy, S., Au-Yeung, S., Robertson, A., Cogger-Ward, H., Richards, G., Allison, C., Bradley, L., Kenny, R., O’Connor, R., & Mosse, D. (2022). Autism and autistic traits in those who died by suicide in England. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 221(5), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.21

Cassidy, S., Bradley, L., Bowen, E., Wigham, S., & Rodgers, J. (2018). Measurement properties of tools used to assess depression in adults with and without autism spectrum conditions: A systematic review. Autism Research, 11(5), 738–754. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1922

Cassidy, S., Bradley, L, Cogger-Ward, H., Graham, J., & Rodgers, J. (2021). Development and Validation of the Autistic Depression Assessment Tool–Adult (ADAT-A) in Autistic Adults. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-358997/v1

Chandrasekhar, T., & Sikich, L. (2015). Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of depression in autism spectrum disorders across the lifespan. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.2/tchandrasekhar

Charlot, L., Deutsch, C. K., Albert, A., Hunt, A., Connor, D. F., Jr, McIlvane, & William, J. (2008). Mood and anxiety symptoms in psychiatric inpatients with autism spectrum disorder and depression. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 1(4), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315860802313947

Clarke, D., Baxter, M., Perry, D., & Prasher, V. (1999). The diagnosis of affective and psychotic disorders in adults with autism: Seven case reports. Autism, 3(2), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613990030020

Cooke, L. B., & Thompson, C. (1998). Seasonal affective disorder and response to light in two patients with learning disability. Journal of Affective Disorders, 48(2–3), 145–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00167-5

Crane, L, Adams, F., Harper, G., Welch, J., & Pellicano, L. (2017). Know your normal: Mental health in young autistic adults. https://www.ambitiousaboutautism.org.uk/the-research

Dao, V., Guetta, M., Giannitelli, M., Doulou, F., Leullier, M., Ghattassi, Z., Cravero, C., & Cohen, D. (2023). Severe self-injurious behaviors in an autistic child with sensory seeking, depressive disorder and anxiety disorder: A focus on the therapeutic interventions. Neuropsychiatrie de l'Enfance et de l'Adolescencehttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurenf.2023.05.007

Forbes, M.K., Baillie, A.J., Batterham, P., Calear, A., Kotov, R., Krueger, R., Markon, K., Mewton, L., Pellicano, L., & Roberts, M. (2023). Reconstructing Psychopathology: A data-driven reorganization of the symptoms in DSM-5.

Ghaziuddin, M., Alessi, N., & Greden, J. F. (1995). Life events and depression in children with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25, 495–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02178296

Ghaziuddin, M., Quinlan, P., & Ghaziuddin, N. (2005). Catatonia in autism: A distinct subtype? Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(1), 102–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00666.x

Goldfarb, Y., Zafrani, O., & Gal, E. (2021). “It’s in my Nature” – Subjective Meanings of Repetitive and Restricted Behaviors and Interests Voiced by Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders. In E. Gal & N. Yirmiya (Eds.), Repetitive and Restricted Behaviors and Interests in Autism Spectrum Disorders: From Neurobiology to Behavior (pp. 13–29). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66445-9_2

Gotham, K., Unruh, K., & Lord, C. (2015). Depression and Its Measurement in Verbal Adolescents and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 19(4), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314536625

Hare, D. J. (1997). The use of cognitive-behavioural therapy with people with Asperger syndrome: A case study. Autism, 1(2), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361397012007

Harrison, R., Jones, B., Gardner, P., & Lawton, R. (2021). Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): An appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed-or multi-method studies. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06122-y

Hedley, D., Uljarević, M., Foley, K. R., Richdale, A., & Trollor, J. (2018). Risk and protective factors underlying depression and suicidal ideation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 35(7), 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22759

Helverschou, S. B., Bakken, T. L., & Martinsen, H. (2009). The Psychopathology in Autism Checklist (PAC): A pilot study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(1), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2008.05.004

Hollocks, M. J., Lerh, J. W., Magiati, I., Meiser-Stedman, R., & Brugha, T. S. (2019). Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 49(4), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291718002283

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Hudson, C. C., Hall, L., & Harkness, K. L. (2019). Prevalence of Depressive Disorders in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Abnorm Child Psychol, 47(1), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0402-1

Hutton, J, Goode, S., Murphy, M., Le Couteur, A., & Rutter, M. (2008). New-onset psychiatric disorders in individuals with autism. Autism, 12(4), 373-390https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361308091650

Hymas, R., Badcock, J.C., & Milne, E. (2022). Loneliness in Autism and Its Association with Anxiety and Depression: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-022-00330-w

Jaswal, V. K., & Akhtar, N. (2018). Being versus appearing socially uninterested: Challenging assumptions about social motivation in autism. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 42, e82. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x18001826

Jha, M.K., Minhajuddin, A., Chin Fatt, C., Kircanski, K., Stringaris, A., Leibenluft, E., & Trivedi, M.H. (2020). Association between irritability and suicidal ideation in three clinical trials of adults with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(13), 2147-2154 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-0769-x

Jordan, A. L., Marczak, M., & Knibbs, J. (2021). ‘I Felt Like I was Floating in Space’: Autistic Adults’ Experiences of Low Mood and Depression. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(5), 1683–1694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04638-6

Kadam, R. A. (2017). Informed consent process: A step further towards making it meaningful! Perspectives in Clinical Research, 8(3), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.4103/picr.PICR_147_16

Kerns, C. M., Kendall, P. C., Berry, L., Souders, M. C., Franklin, M. E., Schultz, R. T., Miller, J., & Herrington, J. (2014). Traditional and atypical presentations of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(11), 2851–2861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2141-7

Kinnaird, E., Stewart, C., & Tchanturia, K. (2019). Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 55, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.09.004

Kovacs, M., Staff, M.H.S., & Kovács, M. (2010). Children's depression inventory 2 (CDI2). Multi-Health Systems (MHS) North Tonawanda, NY.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Legault, M., Bourdon, J.-N., & Poirier, P. (2019). Neurocognitive Variety in Neurotypical Environments: The Source of “Deficit” in Autism. Journal of Behavioral and Brain Science, 09(06), 246–272. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbbs.2019.96019

Long, K., Wood, H., & Holmes, N. (2000). Presentation, assessment and treatment of depression in a young woman with learning disability and autism. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 28(3), 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3156.2000.00056.x

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343.

Lovibond, S.H., & Lovibond, P.F. (1996). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation of Australiahttps://doi.org/10.1037/t01004-000

Maenner, M.J., Shaw, K.A., Baio, J., Washington, A., Patrick, M., DiRienzo, M., Christensen, D. L., Wiggins, L. D., Pettygrove, S., Andrews, J. G., Lopez, M., Hudson, A., Baroud, T., Schwenk, Y., White, T., Rosenberg, C. R., Lee, L. C., Harrington, R. A., Huston, M., . . . Dietz, P. M. (2020). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ, 69(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1

Mayes, S. D., Calhoun, S. L., Murray, M. J., & Zahid, J. (2011). Variables Associated with Anxiety and Depression in Children with Autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 23(4), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-011-9231-7

McHugh, M.L. (2012). Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. https://hrcak.srce.hr/89395

Newson, J.J., Pastukh, V., & Thiagarajan, T.C. (2021). Poor Separation of Clinical Symptom Profiles by DSM-5 Disorder Criteria [Original Research]. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.775762

Oakley, B., Loth, E., & Murphy, D. G. (2021). Autism and mood disorders. International Review of Psychiatry, 33(3), 280–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2021.1872506

Özgen, M. H., & van den Brink, W. (2021). Ketamine self-medication in a patient with autism spectrum disorder and comorbid treatment-resistant depression. Tijdschrift Voor Psychiatrie, 63(12), 890–894. https://doi.org/10.5152/pcp.2022.22037

Ozinci, Z., Kahn, T., & Antar, L. N. (2012). Depression in patients with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatric Annals, 42(8), 293–295.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., & Brennan, S. E. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Park, S.H., Song, Y.J.C., Demetriou, E.A., Pepper, K.L., Thomas, E.E., Hickie, I.B., & Guastella, A.J. (2020). Validation of the 21-item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-21) in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113300 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113300

Perry, D. W., Marston, G. M., Hinder, S. A. J., Munden, A. C., & Roy, A. (2001). The phenomenology of depressive illness in people with a learning disability and autism. Autism, 5(3), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361301005003004

Pfeiffer, P. N., Heisler, M., Piette, J. D., Rogers, M. A. M., & Valenstein, M. (2011). Efficacy of peer support interventions for depression: A meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 33(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.10.002

Pollard, A. J., & Prendergast, M. (2004). Depressive pseudodementia in a child with autism. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 46(7), 485–489. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0012162204000805

Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version, 1(1), b92.

Poulsen, R., Brownlow, C., Lawson, W., & Pellicano, E. (2022). Meaningful research for autistic people? Ask autistics! Autism, 26(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211064421

Rhodes, S. M., Eaton, C. B., Oldridge, J., Rodgers, J., Chan, S., Skouta, E., McKechanie, A. G., Mackie, L., & Stewart, T. M. (2023). Lived experiences of depression in autistic children and adolescents: A qualitative study on child and parent perspectives. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 138, 104516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2023.104516

Sandercock, R. K., Lamarche, E. M., Klinger, M. R., & Klinger, L. G. (2020). Assessing the convergence of self-report and informant measures for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 24(8), 2256–2268.

Schwartzman, J. M., & Bonner, H. R. (2023). Behavioral and Social Activation in Autism and Associations with Youth Depressive Symptoms from Youth and Caregiver Perspectives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disordershttps://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-023-06039-x

Schwartzman, J. M., Williams, Z. J., & Corbett, B. A. (2022). Diagnostic-and sex-based differences in depression symptoms in autistic and neurotypical early adolescents. Autism, 26(1), 256–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211025895

Secci, I., Petigas, L., Cuenod, A., Klauser, P., Kapp, C., Novatti, A., & Armando, M. (2023). Case report: Treatment-resistant depression, multiple trauma exposure and suicidality in an adolescent female with previously undiagnosed Autism Spectrum Disorder [Case Report]. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1151293

Skinner, S. R., Ng, C., McDonald, A., & Walters, T. (2005). A patient with autism and severe depression: Medical and ethical challenges for an adolescent medicine unit. Medical Journal of Australia, 183(8), 422–424.

Stewart, M. E., Barnard, L., Pearson, J., Hasan, R., & O’Brien, G. (2006). Presentation of depression in autism and Asperger syndrome: A review. Autism, 10(1), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361306062013

Storch, E. A., May, E., Jill, W., Jeffrey, J., Jones, A. M., Nadai, De., Alessandro, S., Lewin, A. B., Arnold, E. B., & Murphy, T. K. (2012). Multiple informant agreement on the anxiety disorders interview schedule in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 22(4), 292–299.

Takaoka, K., & Takata, T. (2007). Catatonia in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: Case report and review of literature. Psychological Reports, 101(3), 961–969. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.101.3.961-969

Vidal-Ribas, P., Brotman, M. A., Valdivieso, I., Leibenluft, E., & Stringaris, A. (2016). The Status of Irritability in Psychiatry: A Conceptual and Quantitative Review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(7), 556–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.014

Vogindroukas, I., Stankova, M., Chelas, E. N., & Proedrou, A. (2022). Language and Speech Characteristics in Autism. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 18, 2367–2377. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.S331987

Wachtel, L. E., Griffin, M., & Reti, I. M. (2010). Electroconvulsive therapy in a man with autism experiencing severe depression, catatonia, and self-injury. The Journal of ECT, 26(1), 70–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181a744ec

Watanabe, T. (2021). Treatment of major depressive disorder with autism spectrum disorder by acceptance and commitment therapy matrix. Case Reports in Psychiatry, 2021, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5511232

World Health. (2017). Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders.

Zupanič, S., Kruljac, I., Šoštarič Zvonar, M., & Drobnič Radobuljac, M. (2021). Case report: Adolescent with autism and gender dysphoria. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 671448 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.671448

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Mrs Jessica O’Loghlen for her contribution to inter-rater reliability coding in this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This work was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Stipend Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(CRediT) E.H Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology Project administration Software Validation Visualization Writing – original draft Writing – review & editing. J. P: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization Writing – review & editing. D.A. Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Visualization Writing – review & editing. N.D Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Visualization Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study is a systematic review. The Griffith University Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hinze, E., Paynter, J., Dargue, N. et al. The Presentation of Depression in Depressed Autistic Individuals: A Systematic Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-024-00480-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-024-00480-z