Abstract

Reading is an essential life skill that can lead to independence. However, many individuals with autism and/or intellectual disabilities find this skill difficult to acquire. Computer-assisted instruction (CAI) is one approach that combines recommended reading elements (e.g., phonics, fluency, and comprehension) with evidence-based teaching strategies to support the development of reading skills. The first aim of this systematic review (PROSPERO: CRD42021253686) was to identify CAI reading programs and their effectiveness for individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability. A second aim was to evaluate the views and experiences of those with autism and/or intellectual disability, their teachers, and other stakeholders about CAI reading programs. Electronic searches of 7 databases identified a total of 3539 records for review, with 262 full-text articles evaluated, and 47 papers included in the review for data extraction and quality appraisal. The review identified both single-component and multicomponent CAI reading programs that were commercially available interventions (e.g., Headsprout©, ABRACADABRA) and bespoke interventions (e.g., personalized e-books). Thirty-four of the 47 studies reported positive outcomes in terms of effectiveness. However, the quality of these studies was often poor, and the description of the interventions was often limited (e.g., rationale for the intervention, who delivered it and how), leading to concerns about the rigor of the evidence base. Stakeholders’ views and experiences were reported in half of the evaluated studies. CAI reading programs were reported as enjoyable and easy to use. They were considered effective by the stakeholders. Further research is needed to develop and explore the effectiveness of CAI reading interventions using rigorous study designs, so that individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability can be provided with access to a wider range of evidence-based reading programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) is characterized by impairments in both intellectual and adaptive functioning, such as reasoning, problem-solving, abstract thinking, academic learning, and learning from experience, all of which can have a significant impact on the ability to acquire new skills such as reading (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Autism spectrum disorder is one of the most common co-occurring conditions in individuals with intellectual disability, with an estimated 10% of children with an intellectual disability having autistic symptoms and with 70% of autistic individuals having an intellectual disability (Oeseburg et al., 2010; Schwartz & Neri, 2012). Autism is a cluster of developmental disorders characterized by deficits in communication and social interactions, as well as cognitive processing deficits (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). When a learner has both intellectual disability and autism, the learning challenges faced are greater. For those with an intellectual disability, the added social communication difficulties, repetitive behaviors, and restricted interests associated with a diagnosis of autism result in greater reductions in functional independence (Thurm et al., 2019).

Teaching reading to people with autism and/or an intellectual disability is essential in increasing the likelihood that an individual will be successful in becoming independent, progress through education, and acquire post-school employment (Hosp et al., 2014). In addition, there are social and personal benefits to acquiring reading skills, such as reading for pleasure, communicating via messaging services and social media, and the ability to read important health-related information. These benefits can influence an individual’s overall quality of life (Shurr & Taber-Doughty, 2012) and increase independence.

Reading has been described by Gough and Tunmer (1986) as including decoding, defined as a basic skill involving blending sounds, correlating sounds with the written form (phonics), word reading, and fluency. Reading also involves language comprehension, which is the complex skill of understanding both spoken and written words. These reading skills are highly correlated with language skills (Bishop & Snowling, 2004; McIntyre et al., 2017). Language deficits are often a defining feature, or otherwise concomitant, for many individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability (Nally et al., 2018). There is research evidence showing that individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability are at a higher risk of developing reading delays or difficulties due to language deficits (Nally et al., 2018). Reading difficulties may also arise from social communication and cognitive impairments commonly linked to having a diagnosis of autism or intellectual disability. Social communication difficulties may impact a person’s ability to use perspective-taking, engage in conversations about books, use nonverbal cues to gain meaning from a text, and lead to difficulties in the development of theory of mind (Solari et al., 2021). Cognitive impairments that can impact reading ability include memory deficits, leading to the inability to recall prior knowledge or previously read information from the text (Cain et al., 2001). The tendency for those with autism to focus on specific details at the expense of gaining the general gist of a passage and with difficulties in executive functioning, specifically problem-solving, can also have a detrimental impact on acquiring reading skills (Hume et al., 2009). Deficits can occur in any one, or more of these areas, which can lead to profound literacy difficulties.

The National Reading Panel (NRP, 2000) was assembled to review the effectiveness of research-based approaches to teaching children to read. The key findings from the report indicated that five key elements should be included in all early reading approaches: phonemic awareness, phonics, reading comprehension, vocabulary, and fluency. Effective reading instruction should include more than one, and if possible, all five of the essential components of reading. Research has shown that children and adolescents with developmental disabilities can benefit from comprehensive reading programs that were designed for a population of at-risk or struggling readers (Allor et al., 2014). For example, Allor et al. (2010a) suggest that instruction for students with intellectual disability must be systematic and explicit, include all components of reading (phonics, vocabulary knowledge, comprehension, and fluency), include repetition to make meaningful progress, and be fast-paced and highly motivating. Despite this, instructional reading methods for individuals with intellectual disability typically focus more on teaching isolated sub-skills, such as sight words or phonemic awareness, rather than a multicomponent strategy where teaching is focused on a combination of skills (Allor et al., 2010a, 2010b; Hill, 2016).

One way to implement recommended reading strategies is through computer-assisted instruction (CAI). CAI is defined, for the purpose of the current review, as high-quality computer programs with Internet-based instruction that involve an individual interacting with the instructional materials via the use of information technology equipment (e.g., computer, iPad®, and interactive whiteboards; Hall et al., 2000). The term “computer” signals the use of a single offline computer program, and materials are local to the device, whereas “Internet” refers to the ability to access learning material not only that is local (e.g., on a CD-ROM) but also that is accessed via a network, such as an intranet gateway to the Internet or directly connected to the Internet (Anohina, 2005).

CAI can be considered as one instructional method that can offer an approach to teach reading skills to individuals whose strengths and needs allow for the use of CAI, by combining both the NRP recommended reading elements (e.g., phonics, fluency, and comprehension) with evidence-based teaching strategies (systematic and motivating). Research shows that CAI programs enable people to learn by providing the following: frequent opportunities for active responding, carefully sequenced instruction, immediate feedback after each response so errors can be corrected and accurate responses can be rewarded, consistent instructional delivery, the ability to customize the program for individual learning needs, and auto-monitoring of the accuracy of responses and achievement of skills (Coleman-Martin et al., 2005; Hall et al., 2000; Hill & Flores, 2015).

There is evidence for the effectiveness of CAI when teaching reading skills to the general population or those considered at risk for developing poor reading skills. Cheung and Slavin (2013) conducted a systematic review of the literature to examine the overall effectiveness of educational technology applications on reading outcomes for children with reading disabilities, those with attainment scores in the lower third of the class, and students receiving intensive services such as special education to remediate reading problems in mainstream schools. Twenty high-quality studies demonstrated that educational technology which focused on a range of reading skills (e.g., a phonics program, a program that targeted vocabulary and comprehension) had a positive impact on reading achievements for struggling readers. Rigney et al. (2020) supported this finding in their systematic review of the effectiveness of the different components within the Headsprout© online reading program (early reading and reading comprehension) in both general and special schools (specific participant diagnoses were not provided). Although they concluded that this program is an effective intervention for improving students’ phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension skills, this was a cautious conclusion. Many of the studies included in the Rigney et al. (2020) review were not methodologically sound and did not make use of rigorous designs. Alqahtani (2020) reviewed 45 recently published (2010–2020) studies on technology-based interventions that focused on either the individual areas recommended by the NRP (2000) report or a combination of these areas for children with reading difficulties and found that 41 of 45 studies reported a positive effect when using technology to improve students’ reading skills.

Studies have also examined the effectiveness of CAI on increasing the basic reading skills and more complex reading comprehension skills of people with developmental disabilities. For example, Bailey et al. (2017) found that autistic children made significant gains in their reading skills (e.g., reading accuracy, comprehension, and word-level and passage-level reading) following the use of a computer-based reading program. Similar outcomes in basic reading skills (e.g., reading accuracy, initial sound fluency, and phonemic segmentation fluency) have been observed for those with intellectual disability (Herring et al., 2019; Mandak et al., 2019; O’Sullivan et al., 2017), as well as for more complex reading skills (e.g., reading comprehension and vocabulary; Nally et al., 2021a). However, to date, only two systematic reviews have focused on autistic individuals and have summarized findings from studies that investigated the effectiveness of CAI when teaching reading skills (Khowaja & Salim, 2013; Ramdoss et al., 2011).

Khowaja and Salim (2013) conducted a systematic review of published studies between 2000 and 2011 on developing reading comprehension for autistic children without an intellectual disability, focusing on the isolated reading skills of vocabulary instruction, or text comprehension instruction. Five of the 11 reviewed studies utilized CAI to teach reading comprehension. These studies showed significant improvements in learning performance. However, it is important to be cautious when interpreting this result as the number of studies was limited. Ramdoss et al. (2011) analyzed 12 studies that evaluated the use of CAI to teach literacy skills (defined as reading comprehension, writing, spelling, grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation) to autistic students without an intellectual disability. Once again, the outcome of this systematic review should be interpreted carefully. Some of the reviewed studies reported significant results and large effect sizes, while others reported no improvements. Ramdoss et al. (2011) reported that this may be related to the wide variety of literacy skills targeted for instruction across the studies and the heterogeneity of the students’ needs. Therefore, the researchers were unable to conclude the effectiveness of CAI for teaching literacy skills to autistic students.

Due to the limitations of the previously conducted systematic reviews, the time that has passed since these reviews were completed, and due to the reviews only including those with autism, we conducted a systematic review of the literature to explore the use and effectiveness of CAI in reading for individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability. We also included quality assessments to evaluate the rigor of the studies. In addition, the systematic reviews that have been conducted to date have not reported on the experiences of the teachers and the students who have used CAI for reading. Such data will help evaluate whether those using and implementing the programs judge the interventions and outcomes as acceptable and the effects as socially important. Evidence-based practice is critical for improving outcomes. However, it is important not to solely focus on how effective an intervention is and the outcomes. The views and experiences of stakeholders are also critical to consider if the intervention is going to be implemented in applied settings (Fixsen et al., 2013). Without considering stakeholders’ views, it is unlikely that an effective intervention would be implemented with fidelity and inform long-term practices (Marchant et al., 2012).

The current review addressed the following objectives: (1) to identify computer-based interventions for teaching basic and complex reading skills, such as phonics, fluency, and reading comprehension, to those with autism and/or intellectual disability, (2) to summarize the evidence for the effectiveness for the interventions identified and any factors that contribute to the effectiveness of the intervention, and (3) to evaluate the views and experiences of those with autism and/or intellectual disability, the delivery agents who implemented the intervention (e.g., teachers) and other stakeholders about the effectiveness (e.g., improvements in reading performance), usefulness (e.g., possible benefits of using the CAI program), and ease of using computer-assisted interventions to teach reading.

Method

The protocol for this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO before any searches were conducted (CRD42021253686). The review is reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021).

Eligibility criteria

To identify material to address the review questions, inclusion/exclusion criteria were developed based on (1) participants, (2) intervention, (3) setting, (4) study design, and (5) outcomes. There were no exclusions based on the publication date of the studies.

Participants

Given the focus on autism and/or intellectual disability, at least 75% of reported participants within the study were required to be identified with either autism or an intellectual disability or a diagnosis of co-occurring autism and intellectual disability either via a diagnosis (intellectual disability was determined by an IQ of 70 or below and adaptive behavior tests; autism may have been diagnosed with relevant tools or reported as being given by a professional). Studies were also included if participants were defined administratively as having autism and/or intellectual disability (e.g., enrolled in special school or a special educational needs (SEN) setting in a mainstream provision or receiving health or social care services for these populations) or other clear study reporting. Participants with co-occurring syndromes were included in the review. If participants with autism and/or intellectual disability made up less than 75% of the sample, results were required to be reported separately for the autism/intellectual disability group. This was an arbitrary criterion; however, it ensured that a majority of participants in the studies had autism and/or intellectual disability, and the relevant evidence could be extracted for the review. Studies that did not provide any usable information about the number of individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability within samples were excluded. No exclusions were applied to participants’ age or gender.

Intervention

Eligible studies involved the implementation of individually delivered or group reading interventions. They also included at least one component that was a computerized reading element that could be completed on computers, tablets, iPads®, or interactive boards. The online reading programs could focus on any area of reading development, including the development of phonological awareness, fluency, sight word reading, and reading comprehension skills (as recommended by the NRP Report, 2000). Included interventions were required to have at least two sessions, with a minimum total duration of one hour. We included this criterion to rule out any single session interventions. The reading intervention could be either a multicomponent reading intervention (e.g., an intervention focused on phonemic awareness and vocabulary instruction) or a single-component reading intervention (e.g., a reading fluency intervention). Interventions for other literacy skills such as writing skills, spelling, listening comprehension, and receptive identification skills were excluded. Interventions focused only on the effectiveness of presenting reading materials on information technology (IT) equipment, such as iPads, computers, and whiteboards were also excluded.

Setting

Any setting (e.g., school, home, supported living, and residential settings) in any country was included. Both in-person interventions and remote interventions (via online programs and meetings) were included.

Study Design

Preliminary scoping searches of existing literature found few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of CAI reading interventions for people with autism and/or intellectual disability. Therefore, we included all study designs. Eligible study designs were (a) single-group pre-post design, (b) case series design (with a minimum inclusion of at least two cases), (c) controlled trials, (d) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), (e) single-case experimental designs (SCEDs), and (f) qualitative or quantitative studies reporting data on stakeholders’ views or experiences. Studies that reported no data, reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, case studies with a single participant and no experimental design, conference abstracts, opinion pieces or conceptual papers, and published conference papers were all excluded. In addition, studies reported in a language other than English were also excluded. Sources of gray literature, such as dissertations and non-peer-reviewed publications, were considered.

Outcomes

Outcomes in the present systematic review included, for review objective one (RO1), a list of CAI reading interventions used to teach individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability. For review objective 2 (RO2), any changes to reading skills that were measured through quantitative measures or curriculum-based measurements (e.g., measures of fluency) and standardized reading tests (e.g., the Word Recognition and Phonics Skills Test (WRaPS; Carver & Moseley, 1994). Outcome measures that were part of the intervention program, as well as more distal measures, were included. For review objective 3 (RO3), qualitative outcomes, questionnaires, and rating scales that were used to measure the experiences and views of individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability, the delivery agents, and other stakeholders were included. Other related educational improvements, such as changes in communication and adaptive behavior, were also included outcomes.

Study Selection

Database Searches

Seven online databases (ERIC, Education Research Complete, PsycINFO, British Education Index, Web of Science, ASSIA, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global) were initially searched in April 2021. Updated searches of these databases were completed in May 2022, October 2022, and March 2023.

Search strategies were developed based on terms related to (1) reading, (2) autism and intellectual disability, and (3) CAI. Search terms within each of these lists were separated with OR, and then all three search lines were combined with AND. Table 1 is an example of a search string used in the PsycINFO database. A reference management software program (EndNote) was used to record all search results and to remove any duplications (Table 1).

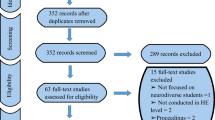

To ensure that the reviewers involved in the screening process were reliable, the first and fourth authors were extensively trained and received ongoing supervision throughout the screening process by experts in conducting systematic reviews. The first author met with the fourth author prior to screening commenced to instruct the fourth author on how to apply the inclusions/exclusion criteria, how to use the bespoke data extraction tool, and how discrepancies would be resolved throughout the screening process. Figure 1 summarizes the study selection process; in total, 3031 records were identified through the first database searches. Titles and abstracts for these records were screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The fourth author independently assessed 30% of randomly selected records, and there was a percentage agreement for inclusion of 90.1% (Cohen’s kappa 0.69; substantial agreement — Landis & Koch, 1977). All records where disagreements occurred were taken through to the full-text screening stage.

PRISMA flow chart illustrating the study selection process. Note: Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow C. D. et al. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal (OPEN ACCESS), BMJ 2021;372: n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

Following title and abstract screening, 230 records were subject to full-text screening, which was completed by the first author. Sixty-nine records (30% of randomly selected texts) were independently screened by the fourth author using a bespoke eligibility checklist where reasons for exclusions were recorded. Of the 69 records, there were 65 agreements (94% agreement; Cohen’s kappa 0.85, almost perfect agreement — Landis & Koch, 1977). Inclusion disagreements were discussed with a third research team member for resolution, and all of these studies were included in the review. A total of 38 records were eligible for inclusion following full-text screening. The first author conducted the quality appraisal assessments of these studies, with the fourth author independently assessing 30% of randomly selected texts. This whole process was completed again in May 2022 where a further three records were identified; in October 2022, where no other records were found; and again in March 2023, where two further records were identified.

The most common reason for articles to be excluded across all searches was not meeting the eligibility criteria that at least 75% of participants had a diagnosis of autism without an intellectual disability, or intellectual disability, or a diagnosis of both autism and intellectual disability (n = 135). Initial records were also excluded based on their study design, the main reason being that the papers were either theoretical or literature reviews (n = 21), and because the intervention did not meet the criteria (n = 60). The full-text paper could not be retrieved for two studies. Forward and backward citation searches were completed for the final set of 43 records, and 5 additional records were found; all except 1 of these 5 studies were included after full-text review.

In total, 47 studies were included in the review, and of these, 41 were published in peer-reviewed journals, and 6 were unpublished theses. One thesis reported two separate studies that were eligible to be included in the systematic review, and these were evaluated separately.

Data Extraction

For RO1 and RO2, data extraction used a piloted bespoke tool that included the following information: participant characteristics, reading skills targeted, details regarding the computer-based instruction, intervention outcomes, assessment of the quality of the study, setting characteristics, experimental design, and assessments used, and for RO3, data on the views and experiences of stakeholders (e.g., delivery agents, such as teachers or parents and individuals who received the interventions).

Data extracted from 30% of randomly selected papers was independently verified by the fourth author who reviewed and confirmed the accuracy of the data extraction. In cases where the information was not considered accurate, the first author and fourth author discussed the information, and the summary was amended to improve its accuracy, and where necessary, other summaries were edited. The resulting information was then used to create descriptive tables for all included studies (see supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Quality Appraisal

The quality of the studies was evaluated. For RO1 and RO2, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist (TIDieR; Hoffman et al., 2014) was used to synthesize information to evaluate the completeness of intervention reporting for each study and the quality of the description of the intervention. This information was included in the bespoke data extraction form. In addition, a narrative synthesis was conducted to provide a summary of the studies, such as the design, method, outcomes, and possible barriers and facilitating factors. The characteristics of the studies are reported in supplementary Table S1. An evaluation of the quality of all included study methods and designs was conducted using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Hong et al., 2018) and the quality indicators tool (QIT; Horner et al., 2005) for single-subject experimental designs.

For RO3, the lack of data available on the views and experiences of stakeholders meant that a formal analysis of the material was not conducted and a narrative synthesis was applied to the findings.

Results

Study Characteristics

Included studies were published between 1998 and 2023, with the highest number of studies being published in 2017 (n = 6; 12.8%) and 2019 (n = 7; 14.9%). Twenty-two studies were conducted in the USA (45.8%) and 11 (22.9%) in the UK. Other studies were conducted in Australia (n = 5; 10.4%), Sweden (n = 2; 4.2%), Ireland (n = 2; 4.2%), Japan (n = 1; 2.1%), Mexico (n = 1; 2.1%), South Africa (n = 1; 2.1%), France (n = 1; 2.1%), and New Zealand (n = 1; 2.1%), and one study did not report this information. Of the 48 studies from the 47 included records (1 thesis contained 2 separately evaluated studies), 24 (50%) reported stakeholders’ views on the intervention.

Participant Characteristics

The reviewed studies included a total of 529 participants. The majority of participants across all studies were identified as being autistic (n = 248; 46.8%), with two studies including those with a diagnosis of Asperger’s and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS). Two-hundred and 22 participants (41.9%) were identified as having intellectual disability specifically four studies included participants with a diagnosis of Down’s syndrome and two studies included those with fragile X syndrome. Thirty-five participants (6.6%) were identified with a diagnosis of both autism and intellectual disability. There were 25 participants (4.7%) who did not fall into 1 of the 3 groups. One paper included four teachers responding to a survey, one paper had a control group of typically developing children (n = 5), and one paper reported that all participants (n = 16) had an intellectual disability and other multiple diagnoses, including autism; however, a breakdown of specific diagnoses was not provided. Thirteen studies detailed secondary diagnoses for participants, which included attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), language difficulties, and hearing and sight impairments. Study samples ranged in size between 3 and 55 (M = 11.4, SD = 11.5) participants. From the studies that reported participants’ age, this ranged between 3 and 32 years old.

Setting

Thirty-three studies (68.7%) implemented the intervention within a school setting; this included mainstream classes (n = 3; 9.1%); specialist units or classes within mainstream schools (n = 6; 18.2%); specialist schools, including general special education settings, autism-specific schools, and specialist summer programs (n = 20; 60.6%); and an autism clinic (n = 1; 3%), and 3 studies were conducted across multiple schools (9.1%). Five studies were conducted in participants’ homes (10.4%), and four studies were conducted across the participants’ homes and other educational structures, such as school and university classes (8.3%). Of the remaining studies, one included an intervention delivered in assistive technology laboratories (2.1%), four in university campus classes (8.3%), and one in a secure hospital (2.1%).

Delivery Agents

Twenty-one studies (43.8%) used familiar teachers or class tutors to deliver the intervention (Arciuli & Bailey, 2019; Burt et al., 2020; Coleman et al., 2015; Coyne et al., 2012; Grindle et al., 2013; Grindle et al., 2020; Grindle et al., 2021; Herring et al., 2019; Hudson, 2019; Mosito et al., 2017; Nally et al., 2021a; O’Sullivan et al., 2017; Pistoljevic & Hulusic, 2019; Plavnick et al., 2016; Roberts-Tyler et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2023; Thompson et al., 2021; Travers et al., 2011; Tyler et al., 2015; von Mentzer et al., 2020; Whitcomb et al., 2011), and 7 studies (14.6%) used a combination of delivery agents such as teachers and parents (Adlof et al., 2018; Bailey et al., 2022; Chitwood, 2014; Hill & Flores, 2015; Jabeen, 2016; Murphy et al., 2022; Tuedor, 2009a). Four interventions (8.3%) were delivered by parents (Grindle et al., 2019; Nally et al., 2021b; Serret et al., 2017; Sugasawara & Yamamoto, 2007), four (8.3%) by researchers (Mandak et al., 2019; McCarthy, 1999; Tuedor, 2009b; Xia, 2019), three (6.3%) by speech therapist/therapists (Bailey et al., 2017; Felix et al., 2017; Henderson-Faranda et al., 2022), and three (4.2%) by graduate/doctoral students (El Zein et al., 2016; Goo et al., 2020; Knight, 2010). Three studies (6.3%) utilized a computerized delivery approach (Saadatzi et al., 2017, 2018a, 2018b), and a further three studies (6.3%) did not report the delivery agent used (Lee & Vail, 2005; Mechling et al., 2007; Tjus et al., 1998).

Intervention Characteristics

Across all studies, the intervention time varied from 5 days to 32 weeks. The most common length of time studies implemented the intervention was between 4 and 6 months (n = 13; 27.1%). Reading interventions were implemented most commonly between two and four times per week (n = 24; 50%), with most sessions lasting between 15 and 20 min (n = 27; 56.2%). Interestingly, 5 studies (10.4%) did not report the number of intervention sessions participants received, 10 studies (20.8%) did not report on the duration of each intervention session, and 10 studies (20.8%) did not report on the length of the intervention.

All studies included in the review are described in supplementary Table S1.

Study Design and Quality

Twenty-four studies (50%) used experimental designs (e.g., mixed-method design, multiple probe design across students, and RCTs). Of the 18 SCEDs (37.5%), 10 used a multiple probe design across participants (20.8%). Six studies (12.5%) used an RCT design (Arciuli & Bailey, 2019; Bailey et al., 2017; Bailey et al., 2022; Grindle et al., 2021; Nally et al., 2021b; Roberts-Tyler et al., 2020).

The quality of the identified studies was generally good. Fourteen studies (29.1%) met all quality criteria, demonstrating excellent methodological quality (MMAT n = 10; QIT n = 4). A further 14 studies (29.1%) met 80% of the MMAT quality criteria and 20 of the 21 (95%) quality indicators. Concerns about study quality included that the outcome assessors were not blind to the intervention procedure, the risk of nonresponse bias was high, outcome data were incomplete, and that social validity was not enhanced by the implementation of the independent variable over extended time periods, by typical delivery agents, and in typical physical and social contexts. Four studies (8.3%) were considered as poorer quality, meeting only 40% or below of the MMAT criteria (Mosito et al., 2017; Pistoljevic & Hulusic, 2019; Roberts-Tyler et al., 2020; Tuedor, 2009a), and four (8.3%) were scored 18/21 (86%) or below on the QIT (Coleman et al., 2015; El Zein et al., 2016; Henderson-Faranda et al., 2022; Whitcomb et al., 2011). In addition, these eight poorer quality studies did not describe the baseline conditions with replicable precision, the baseline data did not provide a repeated pattern of responding that could be used to predict future responding, and measurements were not deemed appropriate to answer the study research questions. For full quality assessment ratings, please see supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

The TIDieR checklist was used to evaluate the quality of reporting about the intervention evaluated in each study. Fourteen studies (29.1%) met all TIDieR checklist criteria (100%). A further 26 studies (54.1%) met between 90 and 100% of the checklist criteria. Twelve of these studies involved the implementation of multicomponent interventions, 9 of which used the Headsprout© online reading program. The main areas of concern for those studies that met less than 90% of the TIDieR checklist were the description of who provided the intervention and the training the delivery agent received, the description of whether modifications were made during the intervention, and if so, what, and the adherence to the fidelity of the intervention (see supplementary Table S5 for the full TIDieR checklist ratings for each study).

Fifty-seven percent of the intervention studies (n = 27) measured outcomes using standardized reading assessments, along with other curriculum-based measurements. For example, studies evaluating the use of Headsprout© commonly measured outcomes using computer-based assessments, such as performance data on episodes completed, alongside a wide variety of standardized assessments. The assessments commonly included the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, specifically the oral reading fluency, retell fluency, and phonemic segmentation fluency subtests (DIBELS; Good et al., 2002); the Woodcock-Johnson-III Passage, specifically the comprehension subtest, letter-word identification, and oral comprehension subtest (Woodcock et al., 2001); the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Dunn & Dunn, 2007); the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability, specifically the reading accuracy and passage-level reading comprehension subtests (NARA-3; Neale, 1999); and the word recognition and phonics skills test (WRAPS; Carver & Moseley, 1994). The remaining studies utilized less formal assessments such as curriculum-based measurements that were often not described in detail, as well as a lone focus on computer-based assessments (e.g., Headsprout© in-program data). For a full breakdown of the assessments used, including specific subtests, please see supplementary Table S1.

Review Objective 1: What CAI Interventions Were identified?

The identified CAI interventions targeted single skills (single-component interventions) or multiple reading skills (multicomponent interventions).

Single-Component CAI Reading Intervention

Twelve studies (26%) evaluated the use of single-component interventions and the impact these had on reading skills.

Of the 12 studies, 6 (50%) focused on implementing interventions with autistic children. Two of these studies evaluated commercially available programs (Space Voyager: El Zein et al., 2016; Dinosight Reader: McCarthy, 1999), while the remaining studies used bespoke interventions. These bespoke interventions involved a range of approaches, such as programs being presented on an iPad using the EasyVSD application (Mandak et al., 2019), and bespoke applications created using commercially available software (Saadatzi et al., 2018b). Four of the six studies (67%) evaluated were aimed at developing autistic individuals’ sight word recognition. The remaining two studies (33%) focused on alphabet letter recognition (Travers et al., 2011) and summarizing the main idea of a text (El Zein et al., 2016).

Three single-component intervention studies (25%) included those with a diagnosis of intellectual disability. All of these studies were bespoke interventions (e.g., using Smartboards and Microsoft PowerPoint™; Mechling et al., 2007) and focused on developing sight word recognition.

Finally, one study (8%) was related to people with a diagnosis of both autism and intellectual disability, and two studies (17%) included both autistic participants and those with a sole diagnosis of intellectual disability. These studies all involved bespoke interventions, such as the use of a virtual classroom with a virtual personal assistant (Saadatzi et al., 2017; Saadatzi et al., 2018b), and all studies targeted sight word recognition.

Multicomponent CAI Reading Interventions

Within the 35 identified multicomponent interventions (74%), the most commonly used reading program was Headsprout©, with 13 studies exploring Headsprout Early Reading© (HER; 28%), 3 studies evaluating HER and Headsprout Reading Comprehension© (HRC) in combination (6%), and 1 study evaluating HRC in isolation (2%).

Eight studies (47%) evaluating Headsprout© included participants with a diagnosis of autism, six included people with an intellectual disability only (35%), and three studies (18%) included a mix of participants with autism only and those with a diagnosis of both autism and intellectual disability. All 17 studies targeted a combination of reading skills, which included phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

Alongside Headsprout©, 11 studies (31%) were identified that used other commercially available reading programs, and 5 studies (14%) focused on bespoke reading packages that were developed specifically for the study.

Six of the 11 commercially available reading program studies (55%) included participants diagnosed with autism. These commercially available programs included ABRACADABRA (Bailey et al., 2017) and the Swedish version of DeltaMessages© (Tjus et al., 1998). Three (60%) of the five bespoke intervention studies focused on those with a diagnosis of autism. These interventions included bespoke e-books (Pistoljevic & Hulusic, 2019) and an individualized science text created on Book Builder© (Knight, 2010).

Only three studies (27%) were identified that evaluated commercially available programs with participants with an intellectual disability. These programs included HATLE (Felix et al., 2017), ABRACADABRA (Murphy et al., 2022), and the Finnish version of GraphoGame (GG) translated from Finnish-Swedish (von Mentzer et al., 2020). Two studies (40%) of the five bespoke intervention studies were evaluated when used with participants with an intellectual disability (Goo et al., 2020; Mosito et al., 2017), and one study identified from the searches did not describe or name the program; therefore, it was unclear as to whether a commercially available or bespoke intervention was used (Burt et al., 2020).

From the 11 commercially available interventions that were evaluated, 2 (18%) included both those with autism and those with autism and intellectual disability. The programs included Reading Eggspress™ (Henderson-Faranda et al., 2022) and a combination of WiggleWorks Island Adventure and Ocean Adventure (Coyne et al., 2012). One study that included participants with both autism and a diagnosis of autism and intellectual disability did not describe or name the program; therefore, it was unclear as to whether a commercially available or bespoke intervention was used (Hudson, 2019).

From the 16 studies that used commercially available and bespoke reading programs, along with the 2 studies that provided limited details to determine the category of intervention, it was identified that 4 (22%) targeted phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension within 1 intervention. Four studies (22%) incorporated the use of an intervention that focused on two reading skills (e.g., phonetic awareness and decoding; Felix et al., 2017; phonological awareness and word recognition; Mosito et al., 2017), and two studies (11%) evaluated the effectiveness of an intervention that combined three reading skills (e.g., sight words, comprehension, sentence construction; Tjus et al., 1998). The majority of multicomponent interventions included between 3 and 6 targeted reading skills (n = 29, 83%).

All studies reported that the multicomponent CAI reading interventions included active responding, sequenced instruction, immediate feedback after each response, and consistent instructional delivery. Only one program (3%) was described as not including customization (Pistoljevic & Hulusic, 2019). Thirty-three intervention studies (70.2%) implemented the reading programs using computers, 10 studies used an iPad® or iPod® (21.3%), 1 study used an interactive board (2.1%), and 3 of the studies (6.4%) presented the intervention on a combination of technology (e.g., an interactive whiteboard and computer). Additional features such as comprehension questions and knowledge quizzes, text, graphics, e-books, animations and games (multimedia content), videos, audio, text-to-speech software, and problem-solving tasks were included in the programs (Tables 2 and 3).

For more specific details about the studies, see supplementary Table S1. Supplementary Table S2 provides a brief overview of the targeted skills and intervention characteristics.

Review Objective 2: How Effective Are CAI Interventions?

Across studies, the effect of CAI on reading skills was inconsistent. In total, 34 studies (72.3%) reported that CAI was effective when teaching reading skills, and of these, 18 studies (56%) had implemented the intervention with autistic participants. Ten studies (21.3%) reported mixed results (some positive outcomes and some participants showed no improvements), and 2 studies (6.4%) reported no improvements when implementing CAI reading interventions.

Four studies (8.3%) were designed to compare the use of teacher-led reading instruction to CAI-led reading programs. Two of these studies reported comparable improvements in reading skills in both the teacher-led and CAI-led conditions, when using a single component, main idea reading comprehension intervention (El Zein et al., 2016), and a multicomponent reading program (Burt et al., 2020). One study reported that reading skills improved more with the single-component CAI reading program that focused on alphabet letter recognition (Travers et al., 2011), and one reported that reading skills improved more with teacher-led single-component (sight words) instruction (Coleman et al., 2015).

Single-Component Reading Interventions

For interventions that targeted a single component of reading, two commercially available programs (16.6%) and eight bespoke interventions (66.6%) were reported as having positive outcomes. Only one bespoke intervention study was found to have mixed results (Jabeen, 2016), and one study did not demonstrate gains (Coleman et al., 2015).

Of the 10 studies that demonstrated significant gains in reading skills, 5 (50%) included autistic-only participants. Three of the studies used bespoke sight word reading interventions, and the remaining two studies implemented commercially available programs that targeted sight word recognition and summarizing the main idea from a text (Dinosight Reader: McCarthy, 1999; Space Voyager: El Zein et al., 2016). Four of the five studies that demonstrated positive outcomes were rated as having good methodological quality, meeting between 90 and 100% of the quality assessment criteria, with three studies meeting 100% of the criteria (McCarthy et al., 1999; Saadatzi et al., 2018b; Travers et al., 2011).

Three studies (25%) reported reading gains for participants with a diagnosis of intellectual disability. All three bespoke interventions targeted sight word recognition, with two studies using SCEDs (Lee & Vail, 2005; Mechling et al., 2007) and one using a within participant multi pre-post design (Sugasawara & Yamamoto, 2007). All three studies were rated as having good methodological quality, meeting between 90 and 100% of the quality assessment criteria.

Three studies (25%) included a mix of both participants with autism and participants with a diagnosis of autism and intellectual disability. Of these three studies, only two reported positive outcomes (Saadatzi et al., 2017, 2018a). These studies used bespoke sight word recognition interventions and used SCEDs. Of all the single-component intervention studies that reported positive outcomes, the study by Saadatzi et al. (2017) is considered to be of excellent overall quality, meeting 100% of the quality indicator criteria as well as 100% of the TIDieR checklist criteria.

The overall quality of reporting for single-component CAI reading interventions is mixed, with six studies meeting 75% or below of the TIDieR checklist criteria and six single-component intervention studies meeting 90% or more of the criteria (Coleman et al., 2015; El Zein et al., 2016; Saadatzi et al., 2017, 2018a; Sugasawara & Yamamoto, 2007; Travers et al., 2011).

We found no studies that used an RCT design or quasi-experimental group design to evaluate single-component CAI reading programs.

Multiple-Component Reading Interventions

Thirty-five studies focused on the use of multicomponent CAI reading interventions, and out of these, 24 (68.5%) reported positive reading outcomes.

Twenty-two of the 35 multicomponent studies (62.8%) targeted 5 reading skills within the same intervention: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension. Of these 22, 17 interventions (77.2%) were the online reading program Headsprout©, and 14 (82.3%) of these reported improved reading skills.

Eight studies (16.6%) evaluated the use of Headsprout© with autistic participants, seven of which reported positive outcomes (e.g., the ability to decode nonsense words improved, Grindle et al., 2013; gains in reading comprehension skills, Grindle et al., 2020; improved accurate responding during an episode, Plavnick et al., 2016; increase in word reading accuracy, Whitcomb et al., 2011). When the studies that reported improved outcomes were evaluated using the quality assessments and TIDieR checklist, only one study was found to be of excellent quality, meeting 100% of both study quality and intervention reporting criteria (Grindle et al., 2013). Of the remaining seven studies, reporting quality was also high with only two studies rated below 80% on either the quality assessment or the TIDieR checklist. In contrast, Xia (2019) used a multiple probe design across three autistic children and found mixed evidence of the potential effectiveness of HER. When evaluated using the MMAT, the study met 95% of the criteria and also 75% of the TIDieR checklist criteria.

Six studies (12.5%) evaluated the effectiveness of Headsprout© with participants with a diagnosis of intellectual disability. Five of these studies reported positive reading gains (e.g., an increase in identifying initial sounds in words and in reading nonsense words, Herring et al., 2019; improvements in basic reading skills, O’Sullivan et al., 2017; improvements in word recognition and fluency, Roberts-Tyler et al., 2020; increases in phonemic awareness, blending, and segmenting, Tyler et al., 2015). Three of these studies are considered to be of excellent quality, scoring between 90 and 100% on both the quality assessment and the TIDieR checklist (Herring et al., 2019; O’Sullivan et al., 2017; Tyler et al., 2015). In contrast, Adlof et al. (2018) used a multiple case series design and found mixed evidence of the potential effectiveness of HER. When evaluated using the MMAT, this study met 60% of the criteria and 67% of the TIDieR checklist criteria.

Three studies (6.2%) included participants with autism and participants with a diagnosis of both autism and intellectual disability (Chitwood, 2014; Grindle et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2023). Two of these studies reported positive reading outcomes; specifically, both reported improvements with reading nonsense words and blending sounds. All three studies are considered to be good quality, scoring 80% or more on the quality assessment criteria, and all scored 100% on the TIDieR checklist.

Three of the 17 multicomponent HER studies used an RCT design (Grindle et al., 2021; Nally et al., 2021b; Roberts-Tyler et al., 2020), with all reporting positive reading outcomes. The participants in the Grindle et al. (2021) study either had a sole diagnosis of autism or were diagnosed with both autism and intellectual disability. Nally et al., (2021a, 2021b) included autistic people only, and Roberts-Tyler et al. (2020) focused on those with a diagnosis of intellectual disability. These studies also met all the criteria on the TIDieR checklist, and two of the studies met 80% of the criteria on the MMAT (Grindle et al., 2021; Nally et al., 2021b).

Other studies of multicomponent CAI reading interventions reported positive reading outcomes, with six commercially available reading programs (12.5%) and four bespoke interventions (8.3%) reporting significant gains.

ABRACADABRA was the next most studied commercially available CAI reading program (n = 4; 8.3%). Three RCT studies evaluated this reading program when implemented with autistic children. The design used in each RCT involved matching pairs of children with similar reading scores and then randomizing one of each pair to the intervention group with the other to the control group. Of these three studies, two reported reading improvements. All three studies met 80% of the MMAT criteria, and their reporting quality was of a high standard (92% — Arciuli & Bailey, 2019; 92% — Bailey et al., 2022; 100% — Bailey et al., 2017). However, Bailey et al. (2017) reported that they were unable to gather information about regular classroom literacy instruction, and it was not clear what impact this had on the outcomes of the study. Six further studies focused on reading interventions for autistic individuals, three of which were commercially available interventions and three were bespoke. From these six studies, one commercial and three bespoke interventions reported improved reading outcomes (Knight, 2010; Pistoljevic & Hulusic, 2019; Serret et al., 2017; Tjus et al., 1998, respectively). However, only one of these studies used a SCED and can be considered of adequate quality (Knight, 2010), as all others scored 60% or below on the quality assessments. Pistoljevic and Hulusic (2019) evaluated the use of bespoke e-books; however, this study did not meet the MMAT screening questions, due to a lack of clarity around the research question.

Five studies used commercially available (n = 3; 6.2%) and bespoke programs (n = 2; 4.1%) to evaluate the effectiveness of reading interventions with individuals with intellectual disability. For one study, it was unclear if a commercially available or bespoke intervention was used (Burt et al., 2020). Of these six studies, three reported improved reading outcomes (Felix et al., 2017; Goo et al., 2020; von Mentzer et al., 2020), two reported mixed results (Mosito et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2022), and one reported no improvements in reading outcomes (Burt et al., 2020). Only two of these studies used a SCED (Goo et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2022), both of which were considered of higher quality (95% QIT criteria met). Felix et al. (2017) and Mosito et al. (2017) implemented less rigorous study designs (non-randomized and nonequivalent group design and one group pre-/post-test design, respectively). No studies used an RCT design.

Only three studies (6.2%) focused on participants with autism and participants with a diagnosis of autism and intellectual disability. Two of these studies were commercially available interventions, and for one, it was unclear if it used a bespoke or commercially available intervention (Hudson, 2019). Coyne et al. (2012) reported positive reading outcomes. When this study was reviewed for quality, however, it was considered as poor, scoring 60% on the quality assessment. The remaining two studies reported mixed results.

Review Objective 3: Views and Experiences of Stakeholders

Twenty-five studies reported on the views and experiences of stakeholders: 6 (24%) reported anecdotal experiences, and 19 (76%) used interviews and/or surveys. Eight (32%) of these studies sought views from parents, 4 of which were the intervention delivery agent, 14 studies (56%) gained the views of teachers, and 9 studies (36%) gathered the views from the people receiving the intervention. Only eight studies (32%) gained the views from two different stakeholders (e.g., parents and teachers).

Of the 25 studies that reported on stakeholders’ views and experiences, 21 (84%) reported an overall positive view of the CAI reading intervention, and 4 studies (16%) reported mixed views including increased stress for parents, decrease in overall reading at home, and an increase in challenging behavior during the intervention (Adlof et al., 2018; Chitwood, 2014).

There was consistent evidence of positive student engagement with the CAI reading programs and reports that they enjoyed using the programs (Coleman et al., 2015; Coyne et al., 2012; Goo et al., 2020). McCarthy (1999) observed that all autistic students came to the computer programs willingly, and their general disposition throughout the sessions was good, suggesting that participants’ engagement was positive. Nally et al. (2021a) distributed a questionnaire to teachers and participants who were all autistic, to examine their views of the reading program. They concluded that 80% of participants demonstrated positive attitudes towards CAI programs, and 70% indicated that they would like to continue using the program.

Studies also reported on the usability of CAI reading programs and any difficulties that arose when implementing the intervention. In general, parents and teachers found the programs easy to implement and use. Difficulties occurred with implementing the recommended number of sessions and supporting activities per week, interruptions to the intervention due to holidays, challenging behavior, and students’ limited IT abilities (Adlof et al., 2018; Bailey et al., 2022; Grindle et al., 2019; Hudson, 2019). Coyne et al. (2021) reported that teachers were able to learn the commercial reading programs to a high level of proficiency, and the teachers indicated that they would like to continue to use the program after the study. Supporting this finding, teachers and parents reported that they felt the reading program was appropriate for the developmental level of the child and strongly supported the appropriateness of the CAI program (Adlof et al., 2018; Lee & Vail, 2005).

Finally, 12 studies evaluated the stakeholders’ views on the outcomes of the reading programs. Overall, teachers reported positive outcomes (e.g., decoding skills improved, Goo et al., 2020), that instruction was able to be differentiated for individuals (e.g., Knight, 2010), and that skills were retained after each intervention session (Thomas et al., 2023). Similarly, Nally et al. (2021a) found that 90% of teachers strongly agreed that the CAI program was an acceptable and effective intervention for students with autism and would recommend it to others. Grindle et al. (2013) reported that there were parental accounts of participants spontaneously engaging in decoding and sounding out words in their community. However, in one study, there were reports of negative effects on the children who had a diagnosis of autism and intellectual disability, and reports of adverse child characteristics increasing at post-intervention (e.g., aggressive and maladaptive behaviors), indicating more stress on the family (Chitwood, 2014).

Discussion

CAI Reading Programs for Individuals with Autism/Intellectual Disability

The CAI reading programs identified within this systematic review predominantly were implemented with people identified either with autism only (n = 23 studies; 48.9%) or intellectual disability only (n = 15; 31.9%). Very few studies focused on individuals who were diagnosed with both autism and intellectual disability or studies that included participants with either autism or intellectual disability and those diagnosed with both conditions (n = 9; 19.1%). For all subgroups of participants, single-component intervention studies targeted the reading sub-skill of sight word recognition (n = 10; 21.2%). The exceptions to this were two studies with autistic participants that targeted the skills of summarizing the main idea of a text and alphabet letter recognition. Interestingly, no studies were identified that used a single-component CAI program to implement phonics instruction. Phonics instruction was typically incorporated within multicomponent programs. Thirty-five multicomponent intervention studies targeted two or more reading skills (e.g., sight words and vocabulary). Headsprout© was commonly used, with eight studies evaluating the program when used with people with an autism only diagnosis, six studies evaluated it with individuals with an intellectual disability, and three studies focused on its use with those with a diagnosis of autism or intellectual disability and people with a diagnosis of both. Eighteen studies across all subgroups of participants used a range of commercially available programs (e.g., ABRACADABRA, Edmark Reading Program) and bespoke interventions. All studies (commercially available and bespoke interventions) described the reading interventions as using active responding, consistent instruction delivery, and systematic instruction within the reading intervention. In addition, all programs included immediate feedback, such as correcting errors that were made and providing rewards for correct responding. As limited interest in reading tasks can lead to noncompliant behavior and, consequently, limited understanding of the text, motivational factors, such as active responding and immediate feedback, are likely to be key components in the reading success of individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability (Basil & Reyes, 2003).

Effectiveness of CAI Reading Programs for Individuals with Autism/Intellectual Disability

In total, 34 studies reported that CAI reading programs (multicomponent and single-component) were effective in improving reading skills, of which 18 studies included an autism only population and 11 studies included those with intellectual disability only. Only three studies reported no improvements. However, the evidence base for CAIs that focus on teaching single-component reading skills, such as sight words, is not yet sufficient to suggest that these interventions are effective in improving reading ability for individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability. The studies did not use rigorous study designs, with no RCTs conducted, for example. There are further reservations about the quality of the studies and the lack of transparency when describing the intervention, with only one study being considered excellent quality (meeting 100% of the TIDieR checklist and the QIT quality assessment). Single-component interventions are important in developing key aspects of reading (e.g., sight words), particularly for those learners who need to focus on developing very specific skills one at a time. Therefore, it is important for further high-quality research to be conducted in this area. However, it is important to acknowledge that to become competent readers, learners must move towards using all reading strategies in combination in order to fluently and accurately read while understanding the meaning of the text.

The evidence for the effectiveness of multicomponent CAI reading programs for individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability might be characterized currently as promising. Six studies used RCT designs to evaluate reading interventions, three of which focused on HER and HRC, and all three included different populations (Grindle et al., 2021 — individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability; Nally et al., 2021b — autism only participants; and Roberts-Tyler et al., 2020 intellectual disability only). Five of these RCTs were rated as good quality, and all were rated as having described the intervention clearly. However, limitations were identified, such as not all participants were able to complete the recommended number of sessions, fidelity data were not collected during the intervention, and the researchers were not blind to the randomization of participants (Grindle et al., 2021; Nally et al., 2021b). Finally, one RCT where the intervention was implemented with those with intellectual disability only met 40% of the MMAT criteria with concerns regarding participants not being comparable at baseline, the outcome assessor not being blind to the intervention, and participants not adhering to the intervention (Roberts-Tyler et al., 2020).

Single-case experimental designs were also used to investigate multicomponent CAI reading programs. Five SCED studies, four of which included participants with autism, only reported positive outcomes, adding further evidence to that of the RCTs. However, again, it is important to take into account when interpreting the results, the quality of the studies, and the thoroughness when describing the intervention. There were no SCEDs that were rated as excellent quality (meeting all of the criteria on the study quality assessment and TIDieR checklist).

The findings of the studies mostly included outcomes for people with individual diagnoses, and there is only a marginal difference between the number of studies that demonstrated positive outcomes for an autism only population (n = 18) compared to intellectual disability only (n = 11). We can conclude that the evaluation of studies can be applied to both these populations. However, few studies had a focus on people with a dual diagnosis of autism and intellectual disability. Thus, any conclusions about the effectiveness of the reading interventions are less clear when applied to this population.

Stakeholders’ Views of CAI Reading Interventions for Individuals with Autism/Intellectual Disability

Only half of the included studies reported data on stakeholders’ views (parents, teachers, and study participants), and these views were sought through surveys and interviews (n = 19 studies; 39.5%), as well as anecdotal accounts (n = 6 studies; 12.5%). In general, CAI programs were reported as enjoyable to use (e.g., reported by participants using a yes/no survey, Saadatzi et al., 2017), easy for delivery agents to implement (e.g., reported by teachers, Bailey et al., 2022; Coyne et al., 2012), and stakeholders reported that the programs were effective in teaching reading skills (e.g., reported by teachers, Goo et al., 2020; reported by parents, Grindle et al., 2013). However, despite a mixed-methods approach to an investigation of the effectiveness of an intervention being identified as crucial (Bazeley, 2018), the details of stakeholders’ views included in the studies within this systematic review were limited. Stakeholders who reported about the individuals’ experiences were typically parents or teachers (n = 9 studies), and children with autism and/or intellectual disability were rarely consulted (n = 6 studies). Within these six studies, four studies reported on the views and experiences of participants with autism only, and two studies included a population of those with autism and/or intellectual disability. Future studies must develop and use effective methods to obtain the views and experiences of children who use the CAI reading programs.

Review Limitations, Future Directions, and Practical Implications

Although the present review was carefully conducted and reported in line with international standards, there are limitations to the evidence reviewed in terms of providing definitive responses to the review questions.

In response to RO1, of the computer-based reading interventions identified in the present systematic review, one program (Headsprout©) accounted for 17 of the evaluation studies — with the next most frequently researched program being the focus of many fewer studies (n = 4 studies, ABRACADABRA). This does not necessarily mean that we should consider Headsprout© to be effective for individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability. Headsprout© has not been evaluated in a programmatic way (e.g., through the development and testing of adaptations needed, to pilot research, through to large-scale definitive RCTs) but in several separate, typically small-scale studies.

Additionally, with only one CAI reading program being the subject of more than 10 evaluations, the choice of potential evidence-based programs for educators is limited. In 2024, this choice will be narrowed further as it has been announced that Headsprout© will no longer be available (http://www.headsprout.com/). The overall limited number of programs evaluated has a significant practical impact on teaching reading skills to individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability, as not all individuals will be motivated by the same CAI content, or may need additional teaching strategies that are not provided by the identified reading program. This lack of evidence-based programs may be a significant barrier for all educators within special education, especially as individualization and diversity are key when teaching this population. Therefore, it is important that higher quality research needs to be conducted on a range of CAI reading programs.

A small number of identified studies investigated the implementation of CAI reading programs that were delivered in the home and facilitated by parents (n = 8). Five of these studies reported positive outcomes, and this supports the potential for implementing CAI reading programs at home for those with autism only and an intellectual disability only. However, this is dependent on the families’ resources and capacity to be able to implement a CAI reading program. In addition, behavior contrast can often occur between settings for individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability, leading to an increase in behaviors that challenge, increasing the stress on the family (Adlof et al., 2018). More research needs to be completed to support parents in the reading education of their children with autism/intellectual disability since the potential for accurate teaching delivery using CAI could be substantial.

Finally, four studies evaluated in this systematic review aimed to compare the implementation of teacher-led instruction with CAI-led reading programs. Although this was not a specific question posed in advance in our review protocol, it does raise an important practical issue. These reviewed studies, however, were not conclusive, and more evidence is needed to guide educators in the best way to implement reading interventions for individuals with autism and/or intellectual disability (i.e., whether CAI could replace traditional teacher-led delivery).

Study quality is essential to consider when evaluating the effectiveness of the identified reading interventions and the factors that may contribute to the intervention’s success (RO2). The quality of intervention reporting was often lacking, leading to questionable validity. For example, the reporting on the planning for and adherence to intervention fidelity was often absent. Little information was provided in the description of the intervention regarding participants’ attending to the program, how this was ensured, and strategies that were implemented to achieve this. In addition, enhancing the social validity of the study by extending the intervention period, where one study implemented an intervention for just 5 days, or using a typical delivery agent in familiar settings was often not considered.

Study quality was also frequently affected by researchers either not controlling for confounding variables or nonrepresentative samples being used. When comparing the number of RCTs found to those identified in a review that investigated the use of technology-based reading interventions for children with reading difficulties (including those with specific learning difficulties), there is a clear contrast. Alqahtani (2020) identified 45 publications, and of these, 24 studies were RCTs, in comparison to the 6 identified in the present review. This further highlights the need for more robust research designs and in particular RCTs to be used with the currently investigated population.

Information about the training that delivery agents received was often lacking in the studies, leaving questions about how rigorous the training was before the implementation of the program and, at times, questions about whether any training was conducted at all. Fewer than half of the studies evaluated (n = 20; 42.5%) provided clear details about the training, and seven studies (14.8%) provided very limited details, often simply stating that training was delivered. This is an area that needs to be developed further, either through more thorough descriptions of the training process in published studies or where training was limited, and the development of a protocol for training delivery agents should be developed.

When evaluating the views and experiences of stakeholders (RO3), very few studies planned for and gathered this information. The role of social validity needs to play a larger part in intervention studies. Positive outcomes may be demonstrated, but if the intervention is not considered socially acceptable, applicable, or feasible by stakeholders, then it is very unlikely that the intervention will be considered by practitioners for use in applied settings (Spear et al., 2013). Future research must place a greater emphasis on collecting rigorous data on the views and experiences of stakeholders.

There are several limitations in the methodology of the present systematic review. First, we attempted to collate and evaluate information about a broad range of reading skills and across several population subgroups. At times, this may have led to a lack of clarity regarding the findings. A meta-analysis would have provided a clearer estimate of the intervention effects. However, the literature was too dispersed to have synthesized the evidence using meta-analysis.

Second, during the study selection process, the fourth author screened 30% of the title and abstracts, full texts, data extraction, and quality appraisals. Double-screening all texts at each stage is recommended (Cochrane Handbook, Higgins et al., 2023). However, due to limited resources, this was not possible for the present systematic review. Therefore, the findings need to be considered in the context of potentially reduced rigor in the study selection process.

In conclusion, we identified 34 single-component and multicomponent CAI reading intervention studies that reported positive reading outcomes. In itself, this is somewhat encouraging given the potential for CAI and other technology-aided instruction for children with autism (Barton et al., 2017) and other developmental disabilities. Such technologies may offer improved access to effective educational interventions, increase the consistency of delivered teaching, and may help to reduce some barriers to access to specialized teaching supports (e.g., children living in rural settings). However, caution is needed when interpreting the outcomes of the current review on reading due to included studies’ research quality. Headsprout© was the most evaluated reading CAI intervention, adding to the evidence for its effectiveness. However, educators have a limited choice of reading programs when selecting an intervention for such a heterogeneous population. In the overall evidence base included in the current review, 10 potentially effective multicomponent CAI programs were commercially available and were adapted to meet the needs of individuals. The potential practical implication of this is that teachers in special education could adapt mainstream approaches to meet the needs of their student population. This could more rapidly increase the number of CAI reading program options available to them than if they were to wait for bespoke programs to be developed and tested.

Data Availability

Information about all studies included in this review is included in the manuscript and supporting materials.

References

Adlof, S. M., Klusek, J., Hoffmann, A., Chitwood, K. L., Brazendale, A., Riley, K., Abbeduto, L. J., & Roberts, J. E. (2018). Reading in children with fragile X syndrome: Phonological awareness and feasibility of intervention. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 123(3), 193–211.

Arciuli, J., & Bailey, B. (2019). Efficacy of ABRACADABRA literacy instruction in a school setting for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 85, 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2018.11.003

Allor, J. H., Champlin, T. M., Gifford, D. B., & Mathes, P. G. (2010a). Methods for increasing the intensity of reading instruction for students with intellectual disabilities. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 45(4), 500–511. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23879756

Allor, J. H., Mathes, P. G., Roberts, J. K., Jones, F. G., & Champlin, T. M. (2010b). Teaching students with moderate intellectual disabilities to read: An experimental examination of a comprehensive reading intervention. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 45(1), 3–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23880147

Allor, J. H., Mathes, P. G., Roberts, J. K., Cheatham, J. P., & Al Otaiba, S. (2014). Is scientifically based reading instruction effective for students with below-average IQs? Exceptional Children, 80, 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402914522208

Alqahtani, S. S. (2020). Technology-based interventions for children with reading difficulties: A literature review from 2010 to 2020. Education Technology Research Development, 68, 3495–3525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09859-1

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text rev.). Washington: American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Anohina, A. (2005). Analysis of the terminology used in the field of virtual learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 8(3), 91–102. http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.8.3.91

Bailey, B., Arciuli, J., & Stancliffe, R. J. (2017). Effects of ABRACADABRA literacy instruction on children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(2), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000138

Bailey, B., Sellwood, D., Rillotta, F., Raghavendra, P., & Arciuli, J. (2022). A trial of online ABRACADABRA literacy instruction with supplementary parent-led shared book reading for children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 124, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104198

Basil, C., & Reyes, S. (2003). Acquisition of literacy skills by children with severe disability. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 19(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1191/0265659003ct242oa

Barton, E. E., Pustejovsky, J. E., Maggin, D. M., & Reichow, B. (2017). Technology-aided instruction and intervention for students with ASD: A meta-analysis using novel methods of estimating effect sizes for single-case research. Remedial and Special Education, 38(6), 371–386.

Bazeley, P. (2018). Integrating Analyses in Mixed Methods Research. Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/97812647190

Bishop, D. V. M., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment: Same or different? Psychological Bulletin, 130, 858–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.858

Burt, C., Graham, L., & Hoang, T. (2020). Effectiveness of computer-assisted vocabulary instruction for secondary students with mild intellectual disability. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2020.1776849

Cain, K., Oakhill, J. V., Barnes, M. A., & Bryant, P. E. (2001). Comprehension skill, inference making ability and their relation to knowledge. Memory and Cognition, 29(6), 850–859.

Carver, C., & Moseley, D. (1994). Group or individual diagnostic test of Word Recognition and Phonic Skills (WRaPS): Manual. Hodder Arnold H&S.

Cheung, A. C. K., & Slavin, R. E. (2013). Effects of educational technology applications on reading outcomes for struggling readers: A best-evidence synthesis. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(3), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.50

Chitwood, K. L. (2014). Reading intervention for children with fragile X syndrome [Doctoral dissertation, University of California Davis]. Davis ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2014. 3637809

Coleman-Martin, M. B., Wolff Heller, K., Cihak, D. F., & Irvine, K. L. (2005). Using computer-assisted instruction and the nonverbal reading approach to teach word identification. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(2), 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576050200020401

Coleman, M. B., Cherry, R. A., Moore, T. C., Park, Y., & Cihak, D. F. (2015). Teaching sight words to elementary students with intellectual disability and autism: A comparison of teacher-directed versus computer-assisted simultaneous prompting. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 53(3), 196–210. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-53.3.196

Coyne, P., Pisha, B., Dalton, B., Zeph, L. A., & Smith, N. C. (2012). Literacy by design: A universal design for learning approach for students with significant intellectual disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 33(3), 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932510381651