Abstract

The perinatal period has challenges for autistic women. This review synthesises evidence on the experiences of autistic women during the perinatal period. This mixed methods evidence synthesis followed JBI guidance for mixed methods systematic reviews. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool assessed study quality. Thematic analysis was used to synthesise findings. Thirteen studies were included. Themes identified included sensory demands of the perinatal period are frequently overwhelming; experiencing healthcare as an autistic person is challenging; parenting as an autistic mother has difficulties but also rewards; predictability and control are important in labour and birth. Individualised care with reasonable adjustments can make a difference to the perinatal experiences of autistic women. Despite challenges, autistic women also have many strengths as mothers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (i.e. autism) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised mainly by challenges with social communication and social interaction and repetitive and restrictive behaviour, often in combination with sensory processing differences (American Psychiatric Association, 2022; National Autistic Society, 2023). Estimates of prevalence vary. The most recent results suggest that 1 in 36 children in the US are autistic (Maenner et al., 2023; Shaw et al., 2021). Autism is thought to be nearly four times as common in boys as in girls (Maenner et al., 2023; CDC, 2023; Fombonne et al., 2011). However, a greater number of girls are receiving a diagnosis in adulthood. This is due to greater awareness of the female autistic phenotype and understanding of differing presentations of autism between males and females (Hull et al., 2020; Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015). Therefore, understanding the challenges faced by autistic women is increasingly important.

The perinatal period is generally defined as from pregnancy to a year post-partum (O'Hara and Wisner, 2014). This period involves considerable physical, social, and mental change and adjustment (Garcia & Yim, 2017). It can consequently be a difficult time for many women and birthing people. Many experience a perinatal mental health condition. Around 12% experience perinatal depression (Woody et al., 2017), 10% experience perinatal anxiety (Dennis et al., 2017), and a small minority, up to 2.6 in 1000, experience postpartum psychosis (Vanderkruik et al., 2017). In the UK, perinatal mental health conditions are the leading cause of postnatal death (MBBRACE, 2022). They lead to increased risk of adverse outcomes in both pregnancy and birth as well as adverse outcomes for children (Howard and Khalifeh, 2020).

Autism is a diverse condition with individuals having varying levels of needs in different sensory, communication, and social areas (Howlin, 2021). The perinatal period can be particularly difficult for autistic women. For instance, due to communication difficulties, it may be hard to communicate pain during labour to health care professionals or to fully process information given by health professionals. Furthermore, autistic adults experience considerable sensory over-reactivity compared to non-autistic adults, and this may become more challenging perinatally. Pregnancy symptoms (e.g. nausea, foetal movements, examinations, and labour pain) and demands of newborn care (e.g. infant crying and touch seeking and breastfeeding) may pose additional sensory demands for autistic mothers. Furthermore, autistic women are predisposed to poorer mental health. Mental health conditions are more prevalent in the autistic population than the non-autistic population (Lai et al., 2019). As history of mental health problems is a risk factor for perinatal mental health problems (Yang et al., 2022; Howard et al., 2020), they may be more likely in autistic women. Reports suggest that autistic people also face many obstacles to accessing appropriate healthcare. Internal barriers include communication differences (e.g. atypical or non-verbal communication styles and slower information processing, Nicolaidis et al., 2015) and perceived stigma (Doherty et al., 2022). External barriers include clinicians’ lack of knowledge and experience working with autistic adults (Maddox et al., 2020) and challenging sensory environments (Doherty et al., 2022; Nicolaidis et al., 2015). Autistic women specifically have also reported that masking their difficulties to healthcare professionals can result in their difficulties being underestimated (Tint and Weiss, 2018). The stigma associated with perinatal mental health problems may prevent many women from seeking support (McLoughlin, 2013). These barriers may increase the risk of untreated physical and mental health conditions; in serious instances, they can result in premature mortality (Mason et al., 2019). Therefore, autistic women might have extra challenges and, as a result, feel negative emotions during the perinatal period due to these barriers.

Previous systematic reviews have looked at some aspects of autistic women’s experiences of the perinatal period. Samuel et al. (2022) identified sensory challenges faced by autistic women during pregnancy and birth. McDonnell and DeLucia (2021) examined experiences and outcomes of pregnancy and experiences of parenthood amongst autistic adults, including both mothers and fathers. Grant et al. (2022) used qualitative evidence including both peer-reviewed primary research and first-hand accounts found in grey literature to explore autistic women’s experiences of infant feeding. However, no systematic review comprehensively summarises the experiences of the perinatal period for autistic women.

The aim of this study was to examine the individual experiences of women with autism during the perinatal period and to investigate common patterns of their interactions with healthcare professionals during this time. To this end, we conducted a mixed methods systematic review, synthesising the literature relating to autistic women’s experiences of the perinatal period (i.e. pregnancy or up to one year post-partum). The primary findings of this review will ultimately inform those who may be working with autistic women during the perinatal period such as midwives, GPs, health visitors, or specialist community perinatal mental health teams, to ensure that appropriate and accessible interventions and support. This review uses identity-first language throughout to reflect the general preference of the autistic community (Kenny et al., 2016; Tabaos et al., 2023).

Methods

This review is a mixed methods synthesis using thematic synthesis. It is reported using the PRISMA 2020 Checklist in Appendix 1.

The review was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidance for mixed methods reviews using a convergent integrated approach to synthesis and integration (Aromataris et al., 2020).

The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (Westgate and O'Mahen, 2023).

Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review includes qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies reporting primary data about the experiences of autistic women, both formally and self-diagnosed, during the perinatal period. We did not impose date limits on eligible studies.

Inclusion:

-

Studies that deal with at least one aspect of autistic women’s experiences of the perinatal period

-

Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies where data from the quantitative or qualitative components could be clearly extracted

-

Published in English

Exclusion:

-

Systematic or literature reviews

-

Correspondence or short communications

-

Full text not available

-

Studies where it was not possible to separate out the experiences of autistic women from the experiences of other populations

Information Sources

The following databases were searched from inception to February 2023: Medline (OVID), PsycInfo (OVID), EMBASE (OVID), CINAHL (EBSCO), and Ethos (theses via the British Library). The reference lists of included studies were hand-searched for additional relevant publications as well as new citations of included studies.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search strategy to seek all available studies was developed.

This comprised three main categories of search terms covering:

-

Pregnancy, maternity, childbirth, postnatal, birth, labour, and antenatal

-

Autism, Asperger’s, and ASD

-

Experience, perspective, interview, focus group, and survey

A copy of the full Medline search strategy is included in Appendix 3.

Study Selection

Eligible studies were de-duplicated using Endnote reference management software (Endnote Team, 2013). The remaining studies were then imported into Rayyan systematic review software (Ouzzani et al., 2016) for screening. Two reviewers (VW and OS) independently screened the first 10% of abstracts, achieving 100% inter-rater reliability. The remaining abstracts were screened by one reviewer (VW). Where it was not possible to tell if a study fitted the eligibility criteria, it was retained to check the full text. The full text of all remaining papers was reviewed against the eligibility criteria, disagreements were resolved by discussion, and reasons for exclusion at this stage were recorded.

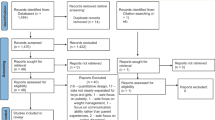

A PRISMA flow diagram is provided to illustrate the study selection process in Appendix 2.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018) was used to appraise the methodological quality of each included study. This instrument is used for systematic reviews that include qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. It assesses the methodological quality of five study categories (qualitative research, randomised controlled trials, non-randomised studies, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed methods studies). Results were summarised in a quality assessment table. Although the authors of the MMAT discourage using a numerical score, some users have created a ranking system for ease of discussion (e.g. Wong et al., 2020). In this review, the studies were rated as high (all criteria met), moderate (three or four out of five criteria met), or low (two or less criteria met). The MMAT was carried out by one reviewer (VW).

Data Extraction Process

For each study, the following data were extracted:

-

Authors, title, and journal

-

Whether person first or identity first language was used

-

Study setting: country, date, and year of data collection

-

Study design: aim, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size and sampling strategy, and methodology

-

Any adaptations made to facilitate the involvement of autistic participants in the study

-

Limitations (identified by author) and any other factors that may affect the results

-

Primary data

An Excel spreadsheet was used to collect the data. The results and discussion sections were directly uploaded into NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd. 2020) for coding into themes. Data extraction was carried out by one reviewer (VW).

Data Synthesis

Data analysis and synthesis followed the JBI guidance for mixed methods systematic reviews (Aromataris and Munn, 2020). This is a technique where studies are ‘grouped for synthesis not by methods…but rather by findings viewed as answering the same research question’ (Sandelowski et al., 2006). A convergent integrated design was followed (Aromataris and Munn, 2020) bringing together both quantitative and qualitative data in the same synthesis.

A process of data transformation (Frantzen & Fetters, 2015) was used to identify and extract the qualitative themes in the quantitative studies, ‘qualitising’ the quantitative data.

A thematic synthesis was carried out using Thomas and Harden’s framework (2008). It involved three stages: coding the data line by line, categorising the codes into descriptive themes, and categorising these descriptive themes into analytical themes. The study themes were coded and analysed using NVivo software by VW; each additional study was coded into pre-existing themes with new ones created when necessary. The themes developed were checked by HOM.

It is not recommended to carry out a GRADE certainty assessment for a mixed methods systematic review following an integrated approach (Aromataris and Munn, 2020).

The first author of this review (VW) notes her own experiences of autism, and the perinatal period may have subconsciously influenced the review. However, this also provided a strong motivation for choosing this piece of research and in wanting to carry it out scrupulously without being led too far by her own thoughts and views. The rigour of the systematic review process itself provided cheques and balances, as did the roles of co-authors (OS, DC, and HOM).

Results

Studies Identified

Database searching identified 5812 records, 21 of which were fully screened against the selection criteria. Fifteen papers were identified for inclusion which represented thirteen individual studies as two studies were each reported across two papers (Hampton et al. (2022b) and Hampton et al. (2023a) were part of the same study as Hampton et al. (2023b) and Hampton et al. (2022c)). The PRISMA flow diagram in Supplementary Material 2 illustrates this process.

Across the thirteen studies, there were 1060 autistic participants and 551 non-autistic participants, ranging from 1 (Rogers et al., 2017) to 24 (Donovan, 2017) autistic participants in the qualitative studies and from 28 (Hampton et al., 2022a) to 417 (Hampton et al., 2022b) autistic participants in the quantitative studies.

Table 1 provides information about the included studies (Table 1).

Quality Assessment

The quality of included papers was of low to high quality when evaluated by the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Table 2 shows the results of the quality assessment (Insert Table 2 ). Five papers were evaluated using the quality criteria for quantitative descriptive studies, and the remaining ten were evaluated using the criteria for qualitative studies. Eight of the qualitative papers were marked as high quality (Burton, 2016; Donovan 2017; Gardner et al., 2016; Hampton et al., 2023b; Hampton et al., 2022c; Lewis et al., 2021; Litchman et al., 2019; Talcer et al., 2023). Two were marked as moderate quality (Rogers et al., 2017; Wilson and Andrassy, 2022): in both papers, it was not possible to tell whether the findings were adequately derived from the data. Four of the quantitative descriptive papers were marked as being of moderate quality as the samples were considered by the authors, not representative (Hampton et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2023a; Pohl et al., 2020). One quantitative descriptive paper was marked as low quality (Lum et al., 2014) as the sample size was insufficient for testing internal consistency reliability because it was a pilot study rather than a full study.

Study Characteristics

Study Focus

Three studies examined the childbirth experience of autistic women (Donovan, 2017; Gardner et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2021). One study looked at healthcare experiences more generally but included a section on maternity (Lum et al., 2014). Another study looked at the sensory experiences of motherhood (Talcer et al., 2023), and one study investigated breastfeeding experiences (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022). The remaining eight studies looked at the perinatal period as a whole including pregnancy, childbirth, the postnatal period, and associated healthcare experiences (Hampton et al., 2022a, b, c; Litchman et al., 2019; Pohl et al., 2020; Rogers et al., 2017). Pregnancy was only reported in two papers (Hampton et al., 2022b, 2022c).

Study Methodology

Four studies/five papers used a quantitative methodology (Hampton et al., 2022a, b, c; Lum et al., 2014; Pohl et al., 2020), and the others used qualitative methodologies.

Of the 10 qualitative papers, semi-structured interviews were the most common approach (Burton, 2016; Donovan, 2017; Hampton et al., 2022c, 2023b; Lewis et al., 2021; Talcer et al., 2023; Wilson & Andrassy; 2022). One paper used an online survey with free-text responses only (Gardner et al., 2016). One study used email communication and a follow-up interview (Rogers et al., 2017), and the last analysed online blogs (Litchman et al., 2019). The most common method of analysis was thematic analysis (Hampton et al., 2022c; 2023b; Litchman et al., 2019; Rogers et al., 2017; Talcer et al., 2023; Wilson & Andrassy, 2022).

Three quantitative papers used an online survey with both forced choice and free-text responses (Hampton et al., 2022b, c; Pohl et al., 2020), another used validated questionnaires (Hampton et al., 2022a), and the last used an online survey.

Study Locations

Two studies were based in the United States (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022; Gardner et al., 2016), two studies were based in Australia (Lum et al., 2014; Rogers et al., 2017), two studies were based in the UK (Burton, 2016; Talcer et al., 2023), and the remaining seven studies were international, although focussed on Western higher income countries. The majority of studies employed a multi-faceted approach to recruitment, using adverts on social media and in local self-help groups as well as through maternity and autism clinics.

Study Limitations Identified by Authors

All but one author identified limitations of their study (Lum et al., 2014). Common themes were small sample size (Burton, 2016; Hampton et al., 2022a; Litchman et al., 2019; Rogers et al., 2017), lack of ethnic diversity amongst participants (Hampton et al., 2022b, c; Lewis et al.; Pohl et al.; Talcer et al., 2023), concern about the representativeness of the autistic participants (Hampton et al., 2022b, c; Hampton et al., 2022c, 2023b; Talcer et al., 2023), an insufficient match between autistic and non-autistic groups (Hampton et al., 2022a; Hampton et al., 2022c, 2023b), autism was self-diagnosed by some women (Gardner et al., 2016; Hampton et al., 2022b, c; Lewis et al., 2021; Pohl et al., 2020), and time passed since the women had given birth potentially affected recall (Donovan, 2017; Pohl et al., 2020).

Use of Language to Describe Autism and Adaptions Made for Autistic Participants

The autistic community generally prefers to use identity first language, i.e. ‘autistic person’ (Kenny et al., 2016; Tabaos et al., 2023); however, five studies used person first language, i.e. ‘person with autism’ (Burton, 2016; Gardner et al., 2016; Litchman et al., 2019; Lum et al., 2014; Rogers et al., 2017). Five studies made specific adaptions to enable autistic women to take part in interviews or surveys including carrying out interviews in different ways such as over a video call, a telephone call, face-to-face or via email or a social messaging application (Donovan, 2017; Hampton et al., 2022a; Lewis et al., 2021; Wilson & Andrassy, 2022), or providing surveys in an alternative paper-based format (Lum et al., 2014). Two studies involved autistic women during the development of the research process (Pohl et al., 2020; Talcer et al., 2023).

Analytical Findings

Data were coded into 92 codes which were then grouped together into 12 descriptive themes. These were used to generate three main analytic themes and one additional theme: sensory demands of the perinatal period are frequently overwhelming; experiencing healthcare as an autistic person is difficult; parenting as an autistic mother has many challenges but also rewards; predictability and control are important in labour and birth. A full list of codes, descriptive themes, and analytic themes are presented in Appendix 3 and are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Sensory Demands of the Perinatal Period Are Frequently Overwhelming

Sensory demands and difficulties fell across all three stages of the perinatal period—pregnancy, labour, and birth—as well as in the hospital environment. Previous coping mechanisms were often not available, although some women did find alternatives.

Pregnancy

Autistic women seemed more prone to sensory difficulties during their pregnancy. Hampton et al. (2022b) found that autistic women were more likely than non-autistic women to report that each sense had been heightened during pregnancy. One woman reported that: ‘I’m more prone to sensory issues’ (Rogers et al., 2017). However, a small subgroup noted that their hearing and touch senses were diminished during pregnancy, reflecting both hypo and hypersensitivity in the autistic population.

Sensory challenges could make daily life more difficult: ‘some things that I would be able to cope with normally, I wouldn’t be able to cope with or would stress me out even more. Just general things like the supermarket and stuff’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Existing coping mechanisms were not always successful: ‘it just kind of comes on very suddenly and a lot more intensely than before, so that’s where the coping strategies that I had before don’t really work’ (Hampton et al., 2023b).

Autistic women also experienced nausea and pain that was worse than that of non-autistic women: 51% of autistic women included in Hampton et al.’s study (2022b) reported experiencing nausea all day, every day. One woman felt that the more severe nausea she experienced was linked to existing sensory sensitivity to smell: ‘maybe it is worse for people with a sensory aversion to smell anyway because it’s heightened’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Hampton et al. (2022b) also found that autistic women were more likely to experience pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy despite adjustment of results to reflect a baseline difference with non-autistic women in the prevalence of hypermobility.

Changing body shape could be challenging: ‘with my body changing shape, my centre of gravity changing, my balance changing, it feels like, OK, I’ve had 30 years to get used to this body and now it’s different, the rules have changed. I have to figure out new ways of moving and being in my body’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Hampton et al. (2022b) found that autistic women were more likely than non-autistic women to describe difficulty adjusting to pregnancy body changes and to report changes in their interoception and proprioception. Internal sensations could be extremely difficult to tolerate: ‘When he (baby) started moving inside me it was unbearable…I used to describe it as having an alien in me’ (Talcer et al., 2023). Another described it as ‘an invasion of privacy’ (Gardner et al., 2016).

Labour and Birth

Sensory differences could pose difficulties during labour and birth. Hampton et al. (2022c) found that autistic women were significantly less likely than non-autistic women to feel aware of their body’s signals and how to interpret them during birth. One woman described how problems with proprioception led to post-birth complications: ‘cos I’m not overly aware of my body, I’ve moved too quickly up the bed, and I accidentally tore my stitches and they got infected’ (Talcer et al., 2023). Another felt that she experienced pain differently to non-autistic women. ‘Cause there was a time in my labor when…I could not speak because it hurt so much. And, I don’t know, I think after the experience and people with autism experience pain differently. Sometimes it seems like we’re tuned up at a higher frequency’. (Donovan, 2017).

A number of women described touch by healthcare professionals during labour as challenging: ‘I found it really difficult when the midwives did an examination of the cervix to see how dilated I was. I couldn’t stop screaming and just about jumped off the bed’ (Rogers et al., 2017). Another said ‘it [labour] was difficult especially when you are having to be touched by medical people, I don’t like being touched at all by anybody… It’s hard to explain but it hurt’ (Talcer et al., 2023). This could seem more challenging than pain: ‘I didn’t have a problem with the contractions and all the other pains, but just having someone touch me while doing all those things would set me over my limits’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). Overload might follow: ‘I felt sensory overload from being touched all day by my baby and the nurse. I didn’t like the nurses touching me. Nurses should ask before doing anything’ (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022).

Sensory difficulties could result in a poor birth experience: ‘I think the perception and lived experience of my son’s birth was definitely made worse by [autism], specifically sensory processing difficulties. The cut of the scalpel, the touch of the doctor’s cold hands, the noises I kept hearing’. (Lewis et al., 2021). Meltdowns or shutdowns sometimes ensued: ‘I was in pain but confined to the bed. And I was all hooked up to the machines and everything. And like all of that was really sensory crazy…I was quite overwhelmed and had a couple of meltdowns’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). Hampton et al. (2023a) found that autistic women were much more likely than non-autistic women to feel overwhelmed by sensory input during birth.

A range of coping mechanisms might be utilised to help with the sensory experiences that occur during labour. Stimming was common: ‘My eyes would go let’s say you have a window, my eyes would go- I would be looking at every line on the blind and following every line down with my eyes. Every single line down because it was soothing’ (Donovan, 2017). Another described flapping her hands and rocking (Donovan, 2017). One appreciated having a doula to help take control of the sensory environment: ‘she made them turn off the lights and put soft music on and she had aromatherapy things that she did’ (Donovan, 2017). Certain tactics could help: ‘I spent a lot of time in the heated birthing bath as it was very warm and I’m sensitive to cold’ (Lewis et al., 2021). Choosing own clothing could be helpful: ‘so being able to just wear my own cotton tank tops that fit close. I like having something close to my skin’. (Donovan, 2017).

Choice of birth location could help with sensory needs. Some women opted for a home birth ‘at home you have control over your environment, you can control the lighting, the noise, you know exactly who is going to be in the room’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Birthing centres were another option: ‘I’m due to go into one of the birthing centres where you can have your own music on and the lights are quite low and they don’t have a lot of people coming in and out’ (Hampton et al., 2023b).

Hospital Environment

The hospital environment was a significant source of sensory distress for many women in the included studies, particularly from noise and light (Gardner et al., 2016). One woman said ‘I find it really hard in the waiting room where I see the midwives because they often have music on and the lights are really bright and it’s just horrible’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). The labour ward posed acute challenges: ‘It was horrific, it was really horrific because you’re having people coming in all the time in the room, the lights are really bright, it’s noisy’ (Talcer et al., 2023). Shutdowns could result: ‘It was a complete sensory overload situation from the noise and lights to the pressure. I became nonverbal under the stress…I found myself so overwhelmed that I could not speak to tell anyone how much pain I was in or to ask for help’ (Lewis et al., 2021).

Hampton et al. (2023a) found that autistic women were more likely to find a postnatal ward overwhelming with regard to sensory input than non-autistic women. One said: ‘then I was in the maternity ward with a new baby that I didn’t really know what to do with, and I was with – there were three other participants in the room and just a curtain separating us. I just needed my own space, cause I’d been in labor 48 h’. (Donovan, 2017).

Looking After a Baby

Once the baby arrived, autistic mothers found three main sensory demands difficult to perform parental tasks: sound, touch, and breastfeeding. Baby cries could be painful: ‘it was like ice down my back, I couldn’t cope with it whatsoever, so I’d go to her instantly to stop it’. (Talcer et al., 2023). Overwhelm could follow: ‘It’s usually when he is crying. I feel overwhelmed, like I can’t take it anymore’ (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022). Toys were noisy: ‘As they get older you’ve got all these brightly coloured, noisy, jangly, interactive, horrible stuff like, like you know, you press a button and bang! You know, so it is very overwhelming’ (Talcer et al., 2023). Breaks were often essential: ‘my husband has complained about me locking myself away in the study. I’m not locking it but you know, going off in here because I need to get away from the noise and have down time’ (Donovan, 2017).

Physical contact with the baby could be difficult: ‘It’s definitely hard when he wants to be on me all of the time, because I’m kind of touch avoidant’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). Another said ‘I get touched-out easily with the kicking and squirming’ (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022). Breastfeeding was an intense form of touch: ‘I breastfed for two years and I got very touched out, to the point where I couldn’t stand my partner touching my arm, that contact can get very overwhelming very quickly’ (Talcer et al., 2023). Medical staff might not recognise the sensory difficulties of breastfeeding: ‘I usually got “that shouldn’t hurt”, like I was a naughty child for getting a pain sensation’ (Rogers et al., 2017). It could be tricky if help was needed: ‘I wasn’t comfortable with the first lactation consultant. She was sitting too close to me on a couch…Second lactation consultant – I was sitting in a chair. She asked me to demo first what we were doing. Then she asked my permission to help, helped from in front of me rather than sitting on my side’ (Gardner et al., 2016).

Women tried different coping mechanisms for breastfeeding: ‘I needed a quiet dark room with no distractions or bright lights to stay calm’ (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022). Another employed distraction techniques ‘I find that concentrating on my phone if I’m struggling, helps’ (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022). Nipple shields could also be helpful: ‘I use nipple shields so there’s a little boundary space between me and my baby. It’s not as much of a sensory trigger with the shield’ (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022).

Hampton et al. (2023a) found that autistic women did not significantly differ from non-autistic women with regard to whether they experienced problems with breastfeeding; however, sensory difficulties are significantly more likely to cause autistic women to struggle with breastfeeding. However, Pohl et al. (2020) found that despite sensory challenges, most autistic women they surveyed were able to successfully breastfeed.

Experiencing Healthcare as an Autistic Person Is Difficult

The autistic women included in these studies often found it difficult to access the healthcare that was needed during the perinatal period and frequently had negative perceptions of it. The biggest challenge was dealing with healthcare professionals: autistic women reported feeling judged, dismissed, or misunderstood. This seemed from their descriptions to originate from both a lack of autism awareness amongst staff and stigma. Communication difficulties worsened women’s healthcare experiences, with a particular challenge for the perinatal period being a disparity between an autistic women’s facial expression and how she was feeling. However, provision of clear information, continuity of care, understanding staff, reasonable adjustments, and advocacy from a supporter were described as helping to prevent or alleviate these problems.

Difficulties at the Interface with Healthcare Professionals

Autistic women reported difficulties with coming into contact with healthcare professionals during the perinatal period. Hampton et al., (2022b, 2023a) found autistic women were significantly less likely than non-autistic women to report being satisfied with the care received during pregnancy or childbirth. One woman reported that there was a lack of support specifically for autistic women during the perinatal period: ‘The medical profession doesn’t seem to understand or care about how pregnancy and Asperger’s syndrome interact. I just feel there is not enough support services for people like me’ (Rogers et al., 2017).

Women often withheld their autism diagnosis from healthcare professionals due to their concern about negative reactions from professionals. In one study (Hampton et al., 2022b, c), only 13% of women disclosed their diagnosis to a doctor or GP and 10% to a midwife, due to concerns about negative reactions: ‘I do not think my midwife or doctor would know what that means or what to do with this info. I fear that would make them doubt my feelings and answers and take me less seriously’. Similarly, Pohl et al. (2020) found that over 80% of mothers worried that disclosure would change a professional’s attitude towards them. Some were concerned about feeling judged: ‘I do feel like people look at us like maybe we’re not entirely for motherhood’ (Donovan, 2017). Some women did disclose and described experiencing stigma: ‘I’ve been asked by a couple of the midwives how I think I can be a mum if I’m autistic’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Others had concerns that if they did ask for help, then they would be at risk of being misdiagnosed with a mental illness. ‘you fear that if you speak to the GP or whoever, or the midwife they’re immediately going to go, “Postnatal depression”, (and think you are a) risk for this family or child or whatever’ (Talcer et al., 2023).

Disclosure could be met with disbelief as professionals lacked knowledge of female autism: ‘I had a doctor the other day say, “I’ve worked with autistic kids, and you’re not like them”’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Pohl et al. (2020) also found that the majority of women surveyed encountered disbelief upon disclosure. It could be overlooked: ‘I don’t think any of them were aware of how to handle autism at all. No-one mentioned it, no-one asked if I was coping, it just never came into play really’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). Some found a lack of understanding: ‘I mentioned it at the first appointment and she was a bit like, “oh, what does that mean?” and I had to explain it’. (Hampton et al., 2023b). One thought that healthcare professionals did not really care: ‘even if you were to explain to them I have Asperger’s it wouldn’t be enough for them… I don’t think there’s enough knowledge or care out there’ (Burton, 2016).

Hampton et al. (2022b) found many felt professionals lacked understanding of the effects of being autistic; they were less likely than non-autistic women to feel taken seriously. One said: ‘I did not want these people who clearly were not taking me seriously to touch me and violate my space because I did not trust them at this point to listen to me if I became uncomfortable’. (Lewis et al., 2021). Some professionals failed to understand shutdowns: ‘when I was crying/shouting they seemed to understand what I was feeling, but most of the time I was shut down and silent and they didn’t seem to understand that it was a shutdown and that I wasn’t able to focus on anything in the room or understand anything being asked of me’ (Hampton et al., 2023a). Hampton et al. (2023a) found that autistic women were significantly less likely than non-autistic women to feel that healthcare professionals listened to their requests.

Individual needs were often secondary to hospital policies: ‘you’re all treated exactly the same it’s like a conveyor belt of pregnant women’ (Burton, 2016). Another reflected on the lack of individualised care: ‘Professionals look at breastfeeding in a very neuro-typically based way. We are all different. Some of us are very dramatic, others are highly logical and literal. Remember one size doesn’t fit all’ (Wilson and Andrassy, 2022). However, a few found disclosure helped healthcare professionals better meet their needs, for example, providing continuity of care (Hampton et al., 2022c).

Communication Difficulties

Communication difficulties between women with autism and healthcare professionals were common. Pohl et al. (2020) found that autistic women were more likely than non-autistic women to experience anxiety when interacting with healthcare professionals. Some women used ‘scripts’, i.e. pre-prepared set phrases, to facilitate their communication with healthcare professionals (Donovan, 2017), but this could also impair communication as one woman explained: ‘I made up answers to the questions because I had no idea. I said the right things at the wrong time, following the script’ (Lewis et al., 2021).

Information processing difficulties could lead to problems with comprehension: ‘Sometimes I might need things explained a couple of times before I actually understand it. And that can be very frustrating to people’ (Donovan, 2017). Healthcare professionals needed to take more time with explanations, ‘it would have been helpful to me if the nurses had explained everything more step by step’ (Donovan, 2017). One woman expressed concern that labour might exacerbate this, ‘am I going to be able to not just communicate during labour but to understand what people are saying to me? If I’m being given any instructions to push or whatever, how am I going to process that?’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Hampton et al. (2022b) found autistic women were less likely to have received as much information as they wanted during antenatal appointments than non-autistic women and were also less likely to feel content with the way that it was given to them.

The way that autistic women presented contributed to significant communication problems. Their facial expressions and tone of voice did not always match how they were feeling, sometimes leading to misinterpretation of their experiences of pain: ‘I’m not one to grimace a lot, I don’t cry a lot…I can just flat out tell you, “this hurts really bad”… I feel like people don’t believe me, cause my face doesn’t necessarily match what I’m trying to say’. (Donovan, 2017). Another reported: ‘my face and tone are not indicators of how much pain or turmoil I am in’ (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022).

Women could sometimes become non-verbal during labour, unable to communicate their needs: ‘I found myself so overwhelmed that I could not speak to tell anyone how much pain I was in or to ask for help’ (Lewis et al., 2021). Another woman reported ‘I was kind of trapped in my body… when I had the nurse patting me on the head and stroking me…I couldn’t say anything to like make her stop’ (Donovan, 2017).

Some found that their communication challenges led healthcare professionals to communicate with their partner or carer instead: ‘I remember that there was a lot of explaining things that were going on to my husband. I did my best in speaking up and saying; “talk to me…don’t talk around me”’ (Donovan, 2017). But healthcare professionals could be concerned if they felt that a woman was being silenced: ‘my husband will take over for me when he realizes that I’m having trouble expressing myself. And sometimes she (the nurse) will be like “let her talk for herself”’ (Donovan, 2017).

Things That Helped

Some women experienced helpful care, and others had ideas for potential adjustments. Advocacy from a supporter such as a partner, other family member, carer, or doula was frequently mentioned across the included studies. One spoke of her partner ‘you’re like my mouthpiece sometimes because I go mute sometimes’. (Burton, 2016). Another used her mother to help: ‘I’ve always tried if I can to have my mum with me at the appointments, because I do struggle sometimes to take in things they say to me’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Hampton et al. (2023a) found that autistic women and non-autistic women were equally likely to have an advocate, but for those who did not, autistic women were much more likely to agree that one would have been helpful. One woman recognised that although she could usually communicate quite well, childbirth might limit her abilities and hired a doula (Donovan, 2017).

Some changes improved autistic women’s experiences. Hampton et al. (2022b) found a small number of women had been given adjustments, including being able to wait for appointments somewhere quiet, longer appointments, having blood tests carried out at home, having an advocate, and being given a temporary social worker. One women described: ‘when they moved me around they put something over my eyes so I wouldn’t be blinded. They told me exactly when people were going to come and who was going to come. They tried to give me my own midwife where possible, so I saw the same person all the time and they told me when they were changing. They gave me my own room so I didn’t have to go on the ward’. (Hampton et al., 2022c).

Continuity of care was found helpful: ‘she understands me so it’s helpful having her instead of having to explain or having someone else who doesn’t understand’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). This was also important postnatally: ‘[My health visitor] knows that I’m not fantastic at socialising and things and how difficult the little one’s been at the start’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). Conversely, lack of it could impact trust: ‘With a new person I find that quite difficult. I felt that I had to kind of strategize, if I said something too concerning I didn’t know how she’d react, so I felt that I had to be super OK and fake it a bit’ (Hampton et al., 2022c).

Autistic women valued provision of clear information. Demonstrations were helpful: ‘A good strategy is to demonstrate what should be done instead of just verbalizing it. It helps the autistic woman understand it they can see it being done as well’ (Donovan, 2017). Clear communication was important: ‘She also told me exactly what she was doing and why she was doing it. She didn’t just touch me without telling me that she was going to do that’ (Rogers et al., 2017). Written information was invaluable (Hampton et al., 2022b; Lum et al., (2014);;: ‘she writes things down as she’s saying them and then gives me the notes so that during the appointment if I’ve kind of lost myself halfway through I can always read the note afterwards’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Face-to-face appointments were often preferred ‘phone calls are difficult. I can do them, but it’s just another stress area’ (Rogers et al., 2017).

One thought that awareness for healthcare professionals was crucial for improving the perinatal care experiences of autistic women: ‘I would…be wanting perhaps midwives to have some sort of understanding of the impact on mothers of being pregnant if you’ve got autism, if you got sensory processing difficulties’ (Talcer et al., 2023). However, an individualised approach could overcome a lack of awareness: ‘[My midwife] doesn’t have a lot of experience of autism but she listens to what I have to say about my experiences and then she adapts’ (Hampton et al., 2023b).

Parenting as an Autistic Mother Has Many Challenges but Also Rewards

Autistic mothers often struggled to connect with other mothers, finding antenatal classes and community groups not autism friendly. Many longed for connection with other autistic mothers and could sometimes find this online. Parenting was frequently challenging due to difficulties with lack of predictability, a sense of an absence of instinctiveness, and pressures on executive functioning. Sometimes mothers were referred to social services or diagnosed with a perinatal mental illness. Yet, many were positive about their experiences of parenting and could identify their strengths in looking after a baby.

Connecting with Other Mothers

It was often difficult for autistic mothers to connect with other mothers. Whilst both Pohl et al. (2020) and Hampton et al. (2022b) found that autistic women were just as likely as non-autistic women to attend antenatal classes, Hampton et al. (2022b) found that autistic women were much more likely to find it difficult to attend, due to classes being too large, too noisy, and with too much pressure to socialise. Some made adaptions that avoided classes: ‘I hired a doula who’s coming to my home to do it and that’s better for us because I don’t like big crowds and groups’ (Hampton et al., 2023b).

Social interaction challenges made making connections in the community and accessing support from peers tricky: ‘they’re like, “If you’re having problems with breastfeeding there’s a breastfeeding café and you can go along and meet all the other breastfeeding mums” and I don’t really feel able to do that’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). This extended to other kinds of group activities: ‘The problems started when I had to take them to playgrounds, groups, baby groups, and also, that’s when, you know, I really start to struggle with too much going on around me and I can’t really carry a conversation’. (Talcer et al.,2023).

However, autistic mothers were keen to meet other autistic mothers to share their experiences. One woman wanted ‘Just somewhere where you can meet other high functioning women who… understand that if you message them and say, “Look, I’ve had a meltdown this morning,”’ (Talcer et al., 2023). An online forum could be one way to meet other autistic mothers: ‘Things were very, very, very tough and thankfully I came across an online parenting forum which was largely frequented by – as it turns out many of us autistic women…so I found a lot of online solidarity’ (Talcer et al., 2023). Those that obtained peer support found it helpful: Hampton et al. (2022b) found that the 5% of autistic respondents who had accessed support from other autistic parents thought it helpful and that the majority of those who did not obtain such peer support would have liked to.

Difficulties with Parenting

Autistic mothers often found parenting challenging and experienced self-doubt: ‘I just thought how could you be a mother when you’ve got issues’ (Burton, 2016). Others felt they lacked instinct looking after a baby: ‘It didn’t come very naturally and I was worried that I wasn’t doing it enough, or doing it right’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). Another said of understanding her baby: ‘without help, it was like walking in the dark’ (Gardner et al., 2016).

The life-changing impact was acknowledged: ‘that is really hard because erm you suddenly realise that your life is never ever going to be the same you know you kind of like have routines about you know like favourite programmes you might sit down to watch at certain times and different stuff and you just realise it’s all gone’ (Burton, 2016). A baby affected routines: ‘I found it very hard to accept the lack of a rigid routine, especially when she was new born, she could wake up any minute so I was on edge the whole time’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). Change of routines could also be unsettling: ‘I think that it (autism) makes it harder is that like when, um her routine changes, like sometimes it can be hard for me to like kind of switch gears. Like if she ate an hour ago then wanted to eat again’ (Donovan, 2017).

Many found that a baby challenged their executive functioning abilities. Pohl et al. (2020) found that autistic mothers struggled more than non-autistic mothers with the multi-tasking that being a parent required as well as fulfilling domestic responsibilities. One said ‘I feel that there’s so much I’m responsible for, so much I have to do, so much that needs to be done and I’m not gonna get any of it done and I’m not going to do it right’ (Donovan, 2017). Having to think about another person all the time contributed to the overload: ‘Just having this extra person, I didn’t know what to do with him, should I hold him? Should I put him down? Things like nappies and… You know, I was quite freaked out … it was so overwhelming…’ (Talcer et al., 2023). Inability to use previous coping mechanisms was hard: ‘Usually when I feel overloaded and therefore low I deal with that by doing very little to recover but you can’t do that with a baby’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). Exhaustion and overwhelm might result: ‘I can always try harder to find ways to cope but like at the end of the day if I’m already tired, I genuinely…I haven’t got the energy to find a way to cope… I haven’t got the energy’ (Talcer et al., 2023).

Autistic mothers sometimes faced referrals to social services, seemingly due to being autistic. One undiagnosed woman’s stimming behaviours in hospital post-delivery were seen as a sign of ‘mental instability’ and led to a referral (Donovan, 2017). Another was honest with her midwife about the meltdowns that she experienced, and this led to an unwarranted referral and consequent breakdown in trust with healthcare professionals ‘I feel like if I say that I’m struggling they’re going to forget all the ways in which I’m coping well. And like with the social services thing being triggered, it has made me feel a bit not sure about what I can and can’t say without it being misunderstood’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Another acknowledged the stigma that led to social services involvement: ‘the biggest issue occurs when people in authority misinterpret us [women with autism] and call in Child Protective Services, when in reality, nothing is wrong’. (Litchman et al., 2019). One woman had their child removed: ‘they’d already kind of made up their minds they were going to be adopted’ (Burton, 2016).

Perinatal Mental Illness

Both Pohl et al. (2020) and Hampton et al., (2022b, 2023a) found a higher incidence of common perinatal mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression amongst autistic women compared with non-autistic women. Perinatal mental illness was rarely mentioned by women featured in the qualitative included studies, suggesting that they were more focussed on challenges relating to their autism than their mental health.

However, some women reported receiving support for perinatal mental health difficulties which they found helpful, particularly as one woman reflected that she would not have been given such support just for their autism: ‘it’s quite nice to have that extra support. I wouldn’t have got that just for my autism which kind of sucks’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). This corresponds with Pohl et al.’s (2020) finding that 61% of autistic mother respondents felt that their diagnosis should merit being offered extra support.

Parenting Strengths

Although the perinatal period presented specific challenges for autistic mothers, many also reported positive experiences of parenting. Pohl et al. (2020) found that motherhood was ‘rewarding’ for 85% of autistic mothers.

Autistic mothers could feel attuned to their babies, particularly the different kinds of crying: ‘You’re so used to looking for the super vague, sub-textual clues from adults but the good thing about babies is that they kind of have universal cries and I’m good at listening to noises’. (Hampton et al., 2022c). Another said ‘I am very sensitive to sounds so I knew their [baby’s] sounds…I was more in tune with their grunts and coos, more so than when I would look at their face’ (Gardner et al., 2016). Sensory abilities were linked by one to her facility to care for her baby: ‘Babies are very sensory-oriented, which I fully understand. In some sense it makes it easier for me to anticipate his needs, like “oh he probably just wants to be held, he needs that contact to feel secure”’ (Hampton et al., 2022c).

Some felt that bonding with their baby was easy: ‘Um I don’t feel like I had any bonding issues with my kids at all. Um I bonded with both of them very quickly and very well’ (Donovan, 2017). Whilst for others bonding did not feel instinctive, they could use their knowledge to develop their bond: ‘I just did what I was told to do and did it to make sure she was comfortable and cared for and loved’ (Donovan, 2017).

Autistic hyper-focus was sometimes described as a strength which could help be a better mother due to motivation around gaining knowledge. One said ‘I prepared well in advance by joining breastfeeding support group moderated by trained breastfeeding peer supporters and lactation consultants…It became my hyper-focus’ (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022). They might interrogate the information available to make decisions regarding their baby: ‘There’s just so much overwhelming statistical research and information out there that it was best for the child, the benefits for the mom and everything else that the choice [of breastfeeding] is easy in my mind’ (Donovan, 2017).

Perseverance could exist alongside hyper-focus, particularly with breastfeeding. ‘I’ve persevered with the breastfeeding… And people have commented that me being so stubborn about it is probably in part because of my autism and I made it into a bit of a special interest and was reading everything and researching everything’ (Hampton et al., 2022c). This was echoed in other studies (Wilson & Andrassy, 2022). New coping mechanisms could be developed, perhaps to aid with executive functioning: ‘what works best is just writing down the stuff that needs to get done. Sometimes it takes me a little while. But, um, I guess you know, like taking a deep breath and letting it out and just tackling one at a time, trying to get to the task’ (Donovan, 2017).

Predictability and Control Is Especially Important in Labour and Birth

The prospect of birth posed problems for autistic women who relied on predictability: ‘there’s the uncertainty of when it’s going to be and how long it’s going to take and what’s going to happen, that uncertainty is adding to my fear of it’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). For those having a second baby, it was hard to comprehend that this experience might be different: ‘Yeah, I didn’t get sick at all for my first labor. And that’s another thing that I struggle with is doing the same thing and getting a different result. My brain does not realize that that’s a possibility’ (Donovan, 2017).

Childbirth impeded the need to feel in control: ‘I do like to be the organizer and be in control. It gives me comfort…Um so being in the hospital, it was a different environment with different noises and different smells, and what was happening to my body. I just didn’t have any control over the rhythm. I felt powerless and outta control’. (Donovan, 2017). Several approaches were used to respond to this lack of control and predictability. Some thought that having a birth plan and visiting the hospital in advance would be helpful: ‘[knowing] just like the room I’m going to be in or the ward, that sort of thing would make a huge difference to me, just so I can anticipate what it sounds like, what it smells like, that would really help’ (Hampton et al., 2023b). Most participants in Donovan’s study (2017) wrote birth plans to communicate their sensory needs, helping to give a sense of control over the situation. One woman regretted not having a birth plan: ‘I think [it] would have been helpful for self-advocacy’ (Gardner et al., 2016). A C-section could remove uncertainty: ‘It [planned c-section birth] was fine because it’s all very formulaic, so you know what’s going to happen and they tell you what they’re doing’. (Talcer et al., 2023).

Discussion

Our systematic review, based on the experiences of over 1000 autistic women and over 500 non-autistic women, identified three main themes and one subtheme. These were overwhelming sensory demands, difficulties with accessing healthcare, being an autistic parent has both challenges and rewards, and predictability and control are important especially in labour. It highlighted the need to adapt healthcare services to make them more accessible to autistic women as well as a need for support for autistic women, whether this was provided by professionals or by peers.

We found that autistic women experienced a number of issues at the interface with healthcare services and professionals. The hospital environment was a significant source of sensory stress for autistic women, both when attending antenatal appointments and giving birth. Overall, healthcare professionals seemed to lack an understanding of autism which could lead to autistic women feeling misunderstood or dismissed. Autistic women also expected to be met with stigma which prevented them from disclosing the condition and from potentially receiving a more positive healthcare experience. The difficulties autistic women reported in navigating healthcare during the perinatal period reflect the well-documented experiences of autistic people accessing healthcare services (e.g. Adams and Young, 2021; Raymaker et al., 2017; Maddox et al., 2020; Nicolaidis et al., 2015). It also echoes problems specifically during the perinatal period with attending maternity healthcare highlighted both by McDonnell and DeLucia’s (2021) and Grant et al.’s (2022) reviews. Such barriers to accessing healthcare can lead to adverse outcomes for autistic people (Doherty et al., 2022).

The studies highlight some points that could help autistic women when accessing healthcare: provision of clear information, continuity of care, compassionate, empathic staff, reasonable adjustments, and advocacy from a supporter. Some of these ideas are mentioned in the Autistic SPACE framework proposed by Doherty et al. (2023). This suggests the need to consider sensory needs, predictability, acceptance, communication, and empathy to aid making healthcare environments more accessible for autistic people. Grant et al. (2022) additionally suggested that clinicians should always seek consent before touching a mother, and that a named healthcare professional would avoid repeating needs to new members of staff. Table 3 lists our recommendations for healthcare professionals working with autistic women in the perinatal period (insert Table 3).

The sensory differences of autistic people are acknowledged as a key component of autism (American Psychiatric Association, 2022; Robertson & Baron-Cohen, 2017) and recognised to cause difficulties in healthcare settings (Strömberg et al., 2021). We found that this was reflected in the included studies where challenges centred around the physical feelings of pregnancy and increased sensory sensitivity, problems with healthcare environments, particularly when giving birth, and difficulties with the sensory demands made by a baby including when breastfeeding. This concurs with the review by Samuel et al. (2022) that investigated the sensory challenges of pregnancy and childbirth for autistic women. Some autistic women were able to develop coping mechanisms, such as breastfeeding in a dark room or choosing to give birth at home or in a midwife-led unit.

In the included studies, autistic women reported finding parenting isolating. They often struggled to attend antenatal classes or groups in the community as these were not accessible for autistic needs, in line with the findings of McDonnell and DeLucia’s review (2021). Peer support was difficult to find except, occasionally, online. It was clear that autistic women would have valued more professional support, which was only available if they experienced co-occurring mental health illness. This also matched the findings of McDonnell and DeLucia (2021). Other challenges of being an autistic mother included an inability to use existing coping mechanisms which could result in exhaustion and overwhelm and the unpredictability of the baby. Some of these issues may be common for many parents but were especially acute for autistic mothers due to characteristics of autism such as rigidity of routine and sensory differences. This may explain the higher incidence of perinatal mental illness amongst autistic mothers than non-autistic mothers (Hampton et al., 2022b, c; Pohl et al., 2020).

Although autistic women could find parenting challenging, it is important to note that many women were positive about their experiences and found that they had certain strengths. This is important as autism research and practise are beginning to move towards strengths-based rather than deficit-based approaches (Urbanowicz et al., 2019; Pellicano et al., 2022). In this review, autistic women highlighted strengths in feeling attuned to their babies, hyperfocus which could motivate them to gain knowledge and make good decisions, and perseverance.

Limitations of the Review

Ethnic diversity amongst participants in the studies was limited with most involving predominantly white participants. All studies were set in highly developed Western countries. This may reflect known challenges amongst the black and minority ethnic communities in obtaining an autism diagnosis. This can be due to either levels of knowledge and understanding of autism being lower in these communities or failures of healthcare professionals recognising autism in this population (Slade, 2014). However, it is important to take a race inclusive perspective to autism research (Giwa Onaiwu, 2020).

Although several of the included studies demonstrated that autistic women were more likely than non-autistic women to experience perinatal mental illness, it was not possible to tell in the qualitative papers which of the experiences reported were a result of this or if it intensified the experiences of the autistic women.

The coding of the data in the review was carried out by a single reviewer, and this may potentially bias the findings; however, all themes developed were discussed with a second reviewer.

Future Research

This review highlights that increasing attention is being paid to the experiences of autistic women during the perinatal period: nine of the fifteen included studies were published since 2020.

Future research needs to recruit a more diverse range of participants to ensure a more representative range of perspectives than white western women. It could specifically examine the experiences of black and minority ethnic autistic women during the perinatal period to see how the experiences of race, autism, and the perinatal period interact. This is likely to be important since black women are 3.7 times more likely, and Asian women 1.7 times more likely, to die giving birth, than white women (MBRRACE, 2022).

Conclusion and Implications of Findings for Policy and Practise

Autistic women have many strengths as parents but can struggle with the sensory demands of pregnancy, labour, and looking after a baby. Accessing healthcare can be challenging, and healthcare professionals may need to make adjustments to their care, particularly with regard to communication and providing a comfortable sensory environment.

A higher incidence of mental illness amongst autistic mothers than non-autistic mothers suggests that autistic mothers may be over-represented in services that aim to meet perinatal mental health needs. This indicates that such services should ensure that they are accessible to autistic women. The review emphasises that many autistic women encountered healthcare professionals that lacked understanding of autism. Services working with women during the perinatal period, such as midwives, hospital staff, general practise, and perinatal mental health teams, should consider upskilling staff to give them confidence to work with this population. Reasonable adjustments to the care provided could make a substantial difference to the experiences of autistic women in the perinatal period and should be made person-centred as recommended by Haydon et al. (2021)

This review highlights that autistic women wanted more support during the perinatal period than was available to them. Support seemed more likely to be offered for mental health conditions than for specific difficulties associated with autism (Hampton et al., 2022c; Rogers et al., 2017). Service commissioners should plan ways to support autistic women during the perinatal period who may not fit the criteria for treatment under a community perinatal mental health team. Peer support was not readily available, but the women included in these studies thought that it would be helpful (Hampton et al., 2022b; Talcer et al., 2023). Establishing groups aimed at this specific population would be valued.

References

Adams, D., & Young, K. (2021). A systematic review of the perceived barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in individuals on the autism spectrum. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(8), 3387–3400.

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR (Fifth edition, text (revision). American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (Eds). (2020). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-24-01

Burton, T. (2016). Exploring the experiences of pregnancy, birth and parenting of mothers with autism spectrum disorder. Doctoral thesis, Staffordshire University. http://eprints.staffs.ac.uk/2636/. Accessed 26 Apr 2024

Dennis, C. L., Falah-Hassani, K., & Shiri, R. (2017). Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(5), 315–323.

Doherty, M., Neilson, S., O’Sullivan, J., Carravallah, L., Johnson, M., Cullen, W., & Shaw, S. C. K. (2022). Barriers to healthcare and self-reported adverse outcomes for autistic adults: A cross-sectional study. British Medical Journal Open, 12, e056904.

Doherty, M., McCowan, S., & Shaw, S. C. (2023). Autistic SPACE: A novel framework for meeting the needs of autistic people in healthcare settings. British Journal of Hospital Medicine (london, England), 84(4), 1–9.

Donovan, J. (2017). The experiences of autistic women during childbirth in the acute care setting. Unpublished PhD dissertation

Endnote Team (2013) Endnote. X9. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate Analytics.

Frantzen, K. K., & Fetters, M. D. (2015). Meta-integration for synthesizing data in a systematic mixed studies review: Insights from research on autism spectrum disorder. Quality Quantity, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0261-6

Fombonne, E., Quirke, S., & Hagen, A. (2011). Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders’. In D. Amaral, D. Geschwind, & G. Dawson (Eds.), Autism Spectrum Disorders (pp. 90–111). Oxford University Press.

Garcia, E. R., & Yim, I. S. (2017). A systematic review of concepts related to women’s empowerment in the perinatal period and their associations with perinatal depressive symptoms and premature birth. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(suppl 2), 347.

Gardner, M., Suplee, P. D., Bloch, J., & Lecks, K. (2016). Exploratory study of childbearing experiences of women with Asperger syndrome. Nursing for Women’s Health, 20(1), 28–37.

Giwa Onaiwu, M. (2020). “They don’t know, don’t show, or don’t care”: Autism’s white privilege problem. Autism in Adulthood, 2(4), 270–272.

Grant, A., Jones, S., Williams, K., Leigh, J., & Brown, A. (2022). Autistic women’s views and experiences of infant feeding: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Autism, 26(6), 1341–1352.

Hampton, S., Allison, C., Aydin, E., Baron-Cohen, S., & Holt, R. (2022a). Autistic mothers’ perinatal well-being and parenting styles. Autism, 26(7), 1805–1820.

Hampton, S., Allison, C., Baron-Cohen, S., & Holt, R. (2022b). Autistic people’s perinatal experiences i: A survey of pregnancy experiences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05754-1

Hampton, S., Man, J., Allison, C., Aydin, E., Baron-Cohen, S., & Holt, R. (2022c). A qualitative exploration of autistic mothers’ experiences II: Childbirth and postnatal experiences. Autism, 26(5), 1165–1175.

Hampton, S., Allison, C., Baron-Cohen, S., & Holt, R. (2023a). Autistic people’s perinatal experiences ii: A survey of childbirth and postnatal experiences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(7), 2749–2763.

Hampton, S., Man, J., Allison, C., Aydin, E., Baron-Cohen, S., & Holt, R. (2023b). A qualitative exploration of autistic mothers’ experiences I: Pregnancy experiences. Autism, 27(5), 1271–1282.

Haydon, C., Doherty, M., & Davidson, I. A. (2021). Autism: Making reasonable adjustments in healthcare. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 82(12), 1–11.

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34, 285–291.

Howard, L. M., & Khalifeh, H. (2020). Perinatal mental health: A review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry, 19(3), 313–327.

Howlin, P. (2021). Adults with autism: Changes in understanding since DSM-111. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 4291–4308.

Hull, L., Petrides, K. V., & Mandy, W. (2020). The female autism phenotype and camouflaging: A narrative review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7, 306–317.

Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442–462.

Knight, M., Bunch, K., Patel, R., Shakespeare, J., Kotnis, R., Kenyon, S., Kurinczuk, J. (Eds.). On behalf of MBRRACE-UK. (2022) Saving lives, improving mothers’ care core report - lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2018–20. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/reports. Accessed 26 Apr 2024

Lai, M. C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry, 2(11), 1013–1027.

Lai, M. C., Kassee, C., Besney, R., Bonato, S., Hull, L., Mandy, W., Szatmari, P., & Ameis, S. H. (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 819–829.

Lewis, L. F., Schirling, H., Beaudoin, E., Scheibner, H., & Cestrone, A. (2021). Exploring the birth stories of women on the autism spectrum. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 50(6), 679–690.

Litchman, M. L., Tran, M. J., Dearden, S. E., Guo, J. W., Simonsen, S. E., & Clark, L. (2019). What women with disabilities write in personal blogs about pregnancy and early motherhood: Qualitative analysis of blogs. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 2(1), e12355.

Lum, M., Garnett, M., & O’Connor, E. (2014). Health communication: A pilot study comparing perceptions of women with and without high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(12), 1713–1721.

Maddox, B. B., Crabbe, S., Beidas, R. S., Brookman-Frazee, L., Cannuscio, C. C., Miller, J. S., Nicolaidis, C., & Mandell, D. S. (2020). “I wouldn’t know where to start”: Perspectives from clinicians, agency leaders, and autistic adults on improving community mental health services for autistic adults. Autism, 24(4), 919–930.

Maenner, M. J., Warren, Z., Williams, A. R., Amoakohene, E., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Fitzgerald, R. T., Furnier, S. M., Hughes, M. M., Ladd-Acosta, C. M., McArthur, D., Pas, E. T., Salinas, A., Vehorn, A., Williams, S., Esler, A., Grzybowski, A., Hall-Lande, J., & Shaw, K. A. (2023). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - Autism and developmental disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 72(2), 1–14.

Mason, D., Ingham, B., Urbanowicz, A., Michael, C., Birtles, H., Woodbury-Smith, M., Brown, T., James, I., Scarlett, C., Nicolaidis, C., & Parr, J. R. (2019). A systematic review of what barriers and facilitators prevent and enable physical healthcare services access for autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(8), 3387–3400.

McDonnell, C. G., & DeLucia, E. A. (2021). Pregnancy and parenthood among autistic adults: Implications for advancing maternal health and parental well-being. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 100–115.

McLoughlin, J. (2013). Stigma associated with postnatal depression: A literature review. British Journal of Midwifery, 21(11), 784–791.

National Autistic Society. (2023). What is autism? https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/what-is-autism [Retrieved 14th April 2024]

National Health Service England. (2023). Perinatal Mental Health. https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/perinatal/ [Retrieved 14th April 2024]

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D. M., Ashkenazy, E., McDonald, K. E., Dern, S., Baggs, A. E., Kapp, S. K., Weiner, M., & Boisclair, W. C. (2015). “Respect the way I need to communicate with you”: Healthcare experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 19(7), 824–831.

O’Hara, M. W., & Wisner, K. L. (2014). Perinatal mental illness: Definition, description and aetiology. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 28(1), 3–12.

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan — A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Pellicano, E., Fatima, U., Hall, G., Heyworth, M., Lawson, W., Lilley, R., Mahony, J., & Stears, M. (2022). A capabilities approach to understanding and supporting autistic adulthood. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1, 624–639.

Pohl, A. L., Crockford, S. K., Blakemore, M., Allison, C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2020). A comparative study of autistic and non-autistic women’s experience of motherhood. Molecular Autism, 11(3) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-019-0304-2

Raymaker, D. M., McDonald, K. E., Ashkenazy, E., Gerrity, M., Baggs, A. M., Kripke, C., Hourston, S., & Nicolaidis, C. (2017). Barriers to healthcare: Instrument development and comparison between autistic adults and adults with and without other disabilities. Autism, 21(8), 972–984.

Robertson, C. E., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2017). Sensory perception in autism. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 18(11), 671–684.

Rogers, C., Lepherd, L., Ganguly, R., & Jacob-Rogers, S. (2017). Perinatal issues for women with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Women Birth, 30(2), e89–e95.

Samuel, P., Yew, R. Y., Hooley, M., Hickey, M., & Stokes, M. A. (2022). Sensory challenges experienced by autistic women during pregnancy and childbirth: A systematic review. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 305(2), 299–311.

Sandelowski, M., Voils, C. I., & Barroso, J. (2006). Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Research in the Schools, 13(1), 29.

Shaw, K. A., Maenner, M. J., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Furnier, S. M., Hughes, M. M., Patrick, M., Pierce, K., Salinas, A., Shenouda, J., Vehorn, A., Warren, Z., Zahorodny, W., Constantino, J. N., DiRienzo, M., Esler, A., Fitzgerald, R. T., Grzybowski, A., & Cogswell, M. E. (2021). Early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 years - Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 70(10), 1–14.

Slade, G. (2014). Diverse perspectives: The challenges for families affected by autism from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities. National Autistic Society. https://s3.chorus-mk.thirdlight.com/file/1573224908/63849355948/width=-1/height=-1/format=-1/fit=scale/t=445333/e=never/k=7c17beeb/Diverse-perspectives-report.pdf. Accessed 26 Apr 2024

Strömberg, M., Liman, L., Bang, P., & Igelström, K. (2021). Experiences of sensory overload and communication barriers by autistic adults in health care settings. Autism in Adulthood, 4(1), 66–75.

Taboas, A., Doepke, K., & Zimmerman, C. (2023). Preferences for identity-first versus person-first language in a US sample of autism stakeholders. Autism, 27(2), 565–570.

Talcer, M. C., Duffy, O., & Pedlow, K. (2023). A qualitative exploration into the sensory experiences of autistic mothers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53, 834–849.

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(45) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Tint, A., & Weiss, J. A. (2018). A qualitative study of the service experiences of women with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 22(8), 928–937.

Urbanowicz, A. (2019). An expert discussion on strengths-based approaches in autism. Autism in Adulthood, 1(2), 82–89.

VanderKruik, R., Barreix, M., Chou, D., Allen, T., Say, L., Cohen, L. S., Cecatti, J. G., Cottler, S., Fawole, O., Filippi, V., Firoz, T., Ghérissi, A., Gichuhi, G. N., Gyte, G., Hindin, M., Jayathilaka, A., Koblinsky, M., Kone, Y., Kostanjsek, N., on behalf of the Maternal Morbidity Working, G. (2017). The global prevalence of postpartum psychosis: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 17, 272. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1427-7

Westgate, V., & O'Mahen, H. (2023) Autistic women’s experiences of the perinatal period: A systematic mixed methods review. PROSPERO CRD42023404172. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023404172. Accessed 26 Apr 2024

Wilson, J. C., & Andrassy, B. (2022). Breastfeeding experiences of autistic women. MCN; American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 47(1), 19–24.

Wong, E., Mavondo, F., & Fisher, J. (2020). Patient feedback to improve quality of patient-centred care in public hospitals: A systematic review of the evidence. BMC Health Services Research, 20, 530. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05383-3

Woody, C. A., Ferrari, A. J., Siskind, D. J., Whiteford, H. A., & Harris, M. G. (2017). A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 219, 86–92.

Yang, K., Wu, J., & Chen, X. (2022). Risk factors of perinatal depression in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 22(63) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03684-3

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Verity Westgate: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draught, and visualisation. Olivia Sewell: investigation. Doretta Caramaschi: supervision and writing—review and editing. Heather O’Mahen: supervision and writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.