Abstract

Autistic females often present differently to autistic males, which can lead to difficulties obtaining a diagnosis and subsequent support. Parenting an autistic daughter has been linked to additional parenting stress compared to parenting an autistic son. However, research in this area is limited. A systematic review was undertaken to synthesise qualitative studies on parental experiences of raising autistic females. Nine studies met the inclusion criteria and thematic synthesis was completed. Six themes were created. The analysis found issues with diagnosis and differences in lived experience compared to autistic males can present significant challenges. Parents can struggle with a range of negative emotions or feel overwhelmed. However, studies also found benefits to parenting an autistic daughter, such as increased confidence in parenting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder, characterised by difficulties with social interaction and communication, accompanied by repetitive behaviours and/or interests that are present from early childhood (World Health Organisation, 2021). In the UK, the prevalence of autism is rising (Russell et al., 2021) and appears to be more prevalent in males (Loomes et al., 2017). Population-based studies suggest that for every three males diagnosed with ASD, only one female is diagnosed, but clinic-based samples show the ratio is closer to four to one (Loomes et al., 2017). However, the reliability of ASD diagnosis has been questioned, as severity and symptom expression vary widely, and diagnostic rates can be affected by contextual and social drivers (Hayes et al., 2018).

There are two prominent theories explaining these apparent gender differences in diagnosis. The first theory suggests that there may be something that ‘protects’ females from developing autism, such as genetics or hormones (Robinson et al., 2013). The second suggests that ASD is more common in females than diagnostic rates would suggest, but current diagnostic tools and criteria are not sufficiently sensitive to identifying ASD in females, as they have been developed based on symptoms seen in male children (Kirkovski et al., 2013). Females with ASD may present differently to males, with studies suggesting females show fewer social difficulties and repetitive behaviours and have higher levels of social motivation compared to autistic males (Head et al., 2014; Hiller et al., 2016; Lai et al., 2015; Lai & Szatmari, 2020). Furthermore, females are more likely to ‘mask’ what may be considered to be more outwardly visible autistic traits (Gould & Ashton-Smith, 2011; Hull et al., 2020). This is thought to be due to females being more greatly influenced by social expectations compared to males, across many cultures (Hull et al., 2020). Theories propose that females are more aware of social expectations and therefore learn strategies to conform to these (Green et al., 2019). However, despite this enhanced social motivation, autistic women may have more difficulties maintaining long-term friendships or relationships than autistic males (Hiller et al., 2014), with studies suggesting autistic women also find it harder to cope with social conflict (Sedgewick et al., 2019). Equally, it is suggested that autistic females’ special interests may be underestimated as they are not always considered ‘atypical’ due to their focus often lying on more relational and ‘socially acceptable’ topics, such as fictional characters, animals or psychology (McFayden et al., 2019; Harrop et al., 2018). Autistic females are also significantly more likely to experience co-occurring internalising disorders, which may mask underlying autistic characteristics, or mean that they receive a diagnosis of the co-occurring condition whilst their autism goes unrecognised (Hull et al., 2020).

As such, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines in the UK recognise that ASD is under-diagnosed in girls (NICE, 2017), which may be partly attributable to current diagnostic processes being based on the male presentation of autism. Following difficulties in receiving a diagnosis, autistic girls may be unable to access the support required or gain an understanding of any difficulties or symptoms they experience which are associated with undiagnosed autism.

For the wider family, seeking and receiving a diagnosis of ASD for their offspring can be challenging (e.g. Corman, 2009; Ooi et al., 2016; Potter, 2016). Pressures on services and waiting times for assessments mean that it can be hard to obtain a timely diagnosis. Lack of appropriate professional support whilst waiting for an assessment can contribute to parenting stress (Elder et al., 2017; Fernell et al., 2013).

Parents of autistic girls have been found to report elevated levels of parenting stress compared to parents of autistic boys and to struggle with the lack of support available (Baldwin & Costley, 2016; Bargiela et al., 2016; Zamora et al., 2014). There may be a multitude of reasons why parenting stress may be increased for parents of autistic girls, likely to be unique and nuanced for each family. This includes evidence that autistic girls experience more health difficulties and access psychiatric and emergency services more frequently (Croen et al., 2015; Holtmann et al., 2007; Tint et al., 2017). Additionally, research has highlighted gender-specific parental concerns regarding specific vulnerabilities faced by autistic girls, including sex-specific puberty issues. Autistic females may experience enhanced sensory and emotional reactions in response to the menarche and menstruation, as well as increased levels of self-injurious behaviours during this time (Cummins et al., 2020; Steward et al., 2018). This can lead some parents to feel so anxious about this period of transition that they seek medical intervention to delay menarche onset. Vulnerability in sexual relationships and potential elevated risk from sexual violence is another considerable concern for parents of autistic girls. A recent systematic review looking at data on sexual violence (Dike et al., 2023) found that nine of twenty-two identified studies reported elevated rates of sexual violence in autistic samples when compared to non-autistic individuals; girls and women were at particular risk. In a qualitative study, Cridland et al., (2014) found that mothers of autistic girls described worrying that their daughters’ tendencies to fixate on things may translate across into sexual relationships, as well as worries about misunderstandings about personal boundaries and relationships, and therefore how to remain safe and avoid sexual exploitation. This may extend to worries about pregnancy as a result of sexual relationships

In addition to these increased concerns about their daughters’ vulnerabilities, parents of autistic girls are likely less able to access appropriate support, due to less being known regarding the clinical needs of autistic women (Tint et al., 2017). Thus, it is not surprising that parents of autistic girls report higher levels of parenting stress.

High parental stress is in itself linked to poorer familial outcomes, such as greater family conflict, elevated parent mental health difficulties and poorer child outcomes (e.g. Barroso et al., 2018; Crouch et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2021; Tomeny, 2017). Therefore, it is important to understand parents’ experiences and perspectives to increase knowledge about what is contributing to parenting stress. This can ultimately inform the development of future services or resources.

Given the known impact of ASD on the child and family and the wait that can be associated with diagnosis, it is essential to develop support for families during this time. The NICE, (2017) guidelines recommended that families of autistic children should have an assessment for their own needs. However, this guidance does not provide any information about what families may need during this time. It would be of most value to develop resources and services based on parents’ experiences to ensure these meet their needs, hopefully reducing the subsequent impact on children and their wider family lives. Thus, this systematic review aims to synthesise findings from studies that have explored the experience of parenting a female daughter with ASD, from their own perspective. This systematic review will provide insight into the lived experience of parenting an autistic daughter, highlighting what support, if any, may be helpful for parents.

Methods

This systematic review followed the steps outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021). The protocol was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (Fuller et al., 2021, CRD42021267393).

Search Strategy

The PCO (population, comparison and outcome search strategy was chosen: (P) the population was parents of autistic girls; (C) the comparison was qualitative literature; and (O) the outcome was their experiences. This approach was reflected in the search terms. Five databases (PsycINFO, MEDLINE, PubMed, Web of Science and SCOPUS) were searched using the following keywords: (‘girls’ OR ‘females’) AND (‘social communication difficulties’ OR ‘autism spectrum condition’ OR ‘neurodevelopmental disorder’ OR ‘ASD’ OR ‘autism’ OR ‘autism spectrum disorder’ OR ‘aspergers’) AND (‘caregivers experience’ OR ‘caregivers view’ OR ‘parent view’ OR ‘parent experiences’ OR ‘family experiences’ OR ‘parent perspective’). Database searches were complemented by searches through reference sections of identified articles, searching Google Scholar, and checking existing systematic reviews in the relevant research area.

Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Qualitative studies reporting parent experiences of raising a girl diagnosed with ASD were eligible for inclusion.

Articles were included if they were (a) empirical, qualitative studies, (b) published in peer-review journals and (c) available in English. To meet eligibility criteria, studies needed to include parents of girls either formally diagnosed or self-diagnosed with ASD and included general parenting experiences rather than focusing on a sole aspect of parenting. The inclusion of studies where parents identified that their daughter/s were autistic without a formal diagnosis was employed due to the sparse literature in this field, combined with the reality that many autistic females remain undiagnosed due to difficulties accessing assessments as well as male-focused diagnostic criteria. Up to 80% of autistic females are thought to remain undiagnosed at 18 years (McCrossin, 2022). This inclusion criteria therefore allowed all literature on parenting experiences to be included. However, it is acknowledged that this may limit conclusions which can be drawn where studies included parents of females without a formal diagnosis.

Studies were excluded if data specific to girls could not be reliably separated from male data. Where data included both parents and their daughters, data for just the parents was extrapolated. There were no restrictions on the date published or sample size.

Study Selection, Quality Assessment and Data Extraction Procedures

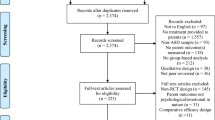

The first author (NH) completed the initial database searches, paper screening and data extraction, with all stages discussed between all authors. Following the removal of one duplicate after initial studies were identified, study titles were then reviewed, followed by abstract and full-text screening. Studies not meeting inclusion criteria were excluded (Fig. 1).

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP UK, n.d.) checklist was used to assess the quality of included studies. The CASP checklist is an appraisal tool designed to assess whether qualitative studies are valid, appraise the results and assess whether these r are considered valuable (CASP UK, n.d.). Previous systematic reviews (e.g. Watson et al., 2021) have deemed studies high in quality if eight to ten of the 10 CASP questions were answered ‘yes’. The first author (NH) gave an initial quality score, and a random selection of studies and their ratings were discussed and reviewed by the authors to check agreement.

A data extraction tool was developed to summarise the details of the articles. This included the following: (a) citation details, (b) sample, (c) geographical origin, (d) design (e.g., qualitative, mixed method), (e) procedure, (f) analysis and (g) results.

Data Synthesis

Thomas & Harden’s, (2008) methods for thematic synthesis were used to combine and analyse the data. Text that was labelled as ‘results’ or ‘findings’ in each article was read line-by-line numerous times to identify emerging themes and concepts, which were listed with accompanying quotes. The list of themes and quotes was reviewed by all authors. Subsequently, the themes were reviewed and structured into groups, and a descriptive theme was created. Due to the powerful nature of the quotes, these were used to illustrate the themes.

The first author (NH) produced a summary of findings, again discussed across authors to ensure agreement on the themes, concepts and quotes, whilst also discussing clinical and future research implications.

Results

Study Characteristics

Nine studies met eligibility criteria and were included in this review. Table 1 provides a detailed summary of the included articles and the result of the CASP quality assessment.

Six studies were conducted in Europe, two in the USA and one study in Australia. Interviews were used in 6/9 studies (Anderson et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2018; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017), one used both individual and group discussions (Milner et al., 2019), and the remaining two studies used focus groups (Gray et al., 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018). Three studies included both mothers and daughters, but data for just the mothers was used (Cook et al., 2018; Cridland et al., 2014; Milner et al., 2019). One study reported on data from parents and Special Educational Needs Coordinators; data for just the parents were extrapolated (Gray et al., 2021).

Analytical techniques varied, with 5/9 using Thematic Analysis (Cook et al., 2018; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Gray et al., 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018; Milner et al., 2019), 3/9 using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA; Anderson et al., 2020; Cridland et al., 2014; Rabbitte et al., 2017), and 1/9 using Naturalistic Inquiry (Navot et al., 2017). Thematic analysis seeks to identify common themes in participants experiences (Terry et al., 2017); IPA attempts to make sense of the participant making sense of their experience to gain meaningful insights and perspectives on the lived experience of the social group (Smith & Shinebourne, 2012); and Naturalistic Inquiry aims to investigate the deep and full meaning of the participants’ experiences using an interactive process (Erlandson et al., 1993).

Predominantly, studies only included mothers of girls with autism (n = 6). Rabbitte et al., (2017) reported including sets of parents, but only one father participated, and one participant was a grandmother. Cook et al., (2018) included one father in their study. One study reported that both mothers and fathers of girls with autism participated equally (Mademtzi et al., 2018) and no studies involved only fathers. Three of the studies interviewed both parents and daughters (Cook et al., 2018; Cridland et al., 2014; Milner et al., 2019), but only data from the mothers were included in the current review.

Across the nine studies, 151 parents of girls with ASD were included. Sample sizes were varied, ranging from three (Gray et al., 2021) to eighty (Mademtzi et al., 2018). Four studies did not clearly report participant ages (Gray et al., 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018; Milner et al., 2019; Navot et al., 2017), but the remaining studies indicated parental ages ranging from 27 to 59 years (Anderson et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2018; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Rabbitte et al., 2017). One study did not clearly state the ages of the daughters of the mothers that were interviewed (Milner et al., 2019); in the other studies, the daughters ranged from ages 4 to 29 (Anderson et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2018; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Gray et al., 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018; Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017). Six out of the nine studies did not report on any ethnic characteristic of the parents or female children, but those that did (Anderson et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2018; Navot et al., 2017) indicated that most participants were Caucasian.

Quality Assessment

Based on the CASP UK (n.d.), quality appraisal, all studies were determined to be high quality (Table 1). However, only 3/9 studies adequately considered the relationship between the researcher and participants (Cook et al., 2018; Gray et al., 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018; Milner et al., 2019; Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017). Most studies required a formal diagnosis of ASD, although Milner et al., (2019), included two participants who had self-diagnosed with ASD. Only one study indicated whether the daughters had a comorbid mental health condition (Navot et al., 2017).

Data Synthesis

Following the process of thematic synthesis, six themes were generated, which are described below. Theme titles were developed based on quotations, to illustrate the experiences of participants. The six themes were (i) ‘Autism is a male thing’; (ii) ‘Nobody wanted to put a diagnosis on it’; (iii) ‘There’s your diagnosis, see ya later’; (iv) ‘Sometimes, I feel so helpless’; (v) ‘Always in mum-mode’, and (vi) ‘We’ve come through the fog’ (see Table 2 for the themes and Table 3 for quotes supporting each theme).

-

(i)

‘Autism is a Male Thing’

Across 6/9 studies, parents compared their experiences with those who had an autistic son (Anderson et al., 2020; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Milner et al., 2019; Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017). These parents felt it was more challenging for those with an autistic daughter due to gender expectations or general misconceptions around ASD. Parents spoke about the lack of awareness when it comes to autistic girls (Anderson et al., 2020;Cridland et al., 2014 ; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021 ; Navot et al., 2017 ; Rabbitte et al., 2017), and how there are misconceptions that girls do not have autism and only boys are autistic (Anderson et al., 2020; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021). There were concerns about how others perceive their daughter, as not ‘looking’ like she is autistic as they do not show traits more typical of autistic boys (Anderson et al., 2020; Cridland et al., 2014; Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017). Parents spoke about how it was more socially acceptable for boys to be aggressive, pay less attention to personal hygiene and how boys are more likely to fit in (Anderson et al., 2020; Cridland et al., 2014; Milner et al., 2019; Navot et al., 2017), as such, autistic boys are more likely to be accepted by typically developing peers (Cridland et al., 2014; Milner et al., 2019). In contrast, some felt that autistic girls find it harder to fit in with both ‘typical’ and autistic populations (Cridland et al., 2014). Parents struggled with their daughters wanting to fit in, which resulted in negative psychological consequences such as feeling sad about their struggles to integrate socially (Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Milner et al., 2019).

-

(ii)

‘Nobody wanted to put a diagnosis on it’

Parents in all studies experienced issues with diagnostic processes and spoke of the subsequent negative impact of a delayed diagnosis. ASD was often missed by professionals, and their daughters were often given other diagnoses, such as anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or oppositional defiant disorder (Anderson et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2018; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017). Whilst these may have been accurate diagnoses, parents described that the focus on these emotional and behavioural symptoms and presentations perhaps delayed the ASD diagnosis, or in some cases meant the ASD assessment was discontinued due to other diagnoses being given.

Parents’ discussed diagnostic issues relating to their daughters copying others’ behaviours and therefore appearing to hide their autistic traits. Parents felt their daughters were good at learning to look like they were coping, so others may not be aware of an ASD diagnosis (Anderson et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2018; Cridland et al., 2014; Gray et al., 2021; Milner et al., 2019; Rabbitte et al., 2017). One mother felt she needed to make their daughter look more impaired to get a diagnosis of ASD and access subsequent support (Mademtzi et al., 2018). Parents spoke of how exhausting their daughters find masking and how it can lead to more difficult presentations in environments where they feel more comfortable to be themselves (Anderson et al., 2020; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021). Most parents had daughters who were diagnosed later in childhood, which had a negative impact on their daughters’ psychological well-being (Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017). Parents expressed that if their daughters had received the diagnosis earlier then they could have accessed earlier intervention, which they felt may have prevented any comorbid mental health difficulties (Cridland et al., 2014).

-

(iii)

‘There’s your diagnosis, see ya later’

In all studies, parents struggled to access support following diagnosis. Some mentioned that receiving lots of information at the time of diagnosis was overwhelming and did not give them adequate space to adjust to the information (Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Gray et al., 2021). When information was provided, parents highlighted a lack of resources specific for autistic girls (Anderson et al., 2020). Similarly, parents felt support services were not specifically developed for girls. Some felt that services or education systems, such as schools, sometimes responded inappropriately to their daughters, such as sending them home for behaviours that were part of their autism presentation, or schools saying they did not know what to do with their daughter (Cook et al., 2018; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Gray et al., 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018; Milner et al., 2019; Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017). Other parents were highlighted as a significant source of support and many participants mentioned that they would struggle without peer support (Anderson et al., 2020; Cridland et al., 2014). Online support groups were particularly highlighted as being a positive source of support. Parents reported feeling less isolated when they connected with other parents with daughters diagnosed with ASD (Anderson et al., 2020; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Gray et al., 2021).

-

(iv)

‘Sometimes, I feel so helpless’

This theme incorporates the wide-ranging difficult emotions that parents described in relation to having a daughter with ASD, including an overwhelming sense of helplessness and worry about their daughters’ ability to manage aspects of daily life and independence. Parents in all studies spoke about negative emotions, such as guilt, worry and grief. Participants described feeling guilty about how they had reacted to or treated their daughter before they knew of the diagnosis, and how they can still struggle to understand their daughter (Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017). Prevailing concerns focus on independence for their daughter, and how they will cope with increasing demands throughout their life, such as going to university or managing romantic relationships (Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018; Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017). They also worried about their daughters’ vulnerability regarding sex and relationships, with many worried their daughter would be ‘taken advantage of’ by others (Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018; Navot et al., 2017).

Parents also grieved for the expectations they had held in their minds for their daughter before the diagnosis. They reported grieving for the relationship they had hoped and expected to have with their daughter (Anderson et al., 2020; Navot et al., 2017), as well as grieving for the life experiences they now think their daughters would not have, such as marriage and children (Cridland et al., 2014; Milner et al., 2019; Navot et al., 2017).

Some parents also struggled with the loss of their own independence, which they had expected to gain back at an earlier age if their children were not autistic and therefore able to manage more independently (Anderson et al., 2020; Cridland et al., 2014). A few parents also referred to struggling with the demands of having an autistic daughter, with some reporting they feel exhausted, drained and overwhelmed (Anderson et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2018; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Gray et al., 2021).

-

(xxii)

‘Always in mum-mode’

Linked to the previous theme, this theme relates to parents feeling overwhelmed. It captures how the parents reported feeling there are extra responsibilities when caring for an autistic daughter, and that they need to think about their daughters’ needs at all times. In 5/9 studies, parents spoke of how they were more involved in their daughters’ lives than those of neurotypical children (Anderson et al., 2020; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018; Navot et al., 2017). They described needing to spend extra time thinking and planning for situations (Anderson et al., 2020), and how they felt responsible for supporting their daughters with social relationships (Anderson et al., 2020; Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018). Four studies referred to additional support being provided to prompt their daughters to attend to their personal hygiene (Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018; Navot et al., 2017). They spoke about having to remind their daughters to shower, supporting their daughters with clothing choices, and having to provide additional support during puberty and menstruation, such as prompting them to change or appropriately dispose of sanitary products (Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Mademtzi et al., 2018; Navot et al., 2017).

-

(vi)

‘We’ve come through the fog’

Despite the challenges, parents in 6/9 studies shared positive aspects of supporting an autistic daughter. Since their daughters had received their ASD diagnoses, parents reported having an increased understanding of their daughters, which they felt enabled them to be better parents (Anderson et al., 2020; Gray et al., 2021; Navot et al., 2017; Rabbitte et al., 2017). They became more confident in their parenting ability as they realised their daughters’ struggles were not due to their parenting and they could research strategies to help (Anderson et al., 2020; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Rabbitte et al., 2017). They also spoke about positive changes within themselves, such as building their resilience (Anderson et al., 2020; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021), increased empathy (Anderson et al., 2020; Rabbitte et al., 2017) and increased knowledge (Anderson et al., 2020; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021). Some reported it was also rewarding to see the progress their daughter had made and how accepting and embracing their differences was helpful (Cridland et al., 2014; Fowler & O’Connor, 2021; Rabbitte et al., 2017).

Discussion

The systematic review aimed to synthesise findings of studies that investigated parents’ experiences of raising autistic girls to provide further insight into parental experiences. It is hoped that this review will inform clinical practice, as it is highlighted that parents of autistic girls experience significant parenting stress (Zamora et al., 2014). This systematic review identified nine studies reporting on the qualitative experience of parents living with an autistic daughter. Thematic analysis identified six themes across the studies, summarising the experiences of 151 parents of girls with ASD. These themes were (i) ‘Autism is a male thing’; (ii) ‘Nobody wanted to put a diagnosis on it’; (iii) ‘There’s your diagnosis, see ya later’; (iv) ‘Sometimes, I feel so helpless’; (v) ‘We’ve come through the fog’; and (vi) ‘Always in mum-mode’.

One of the most striking experiences noted by this review was the psychosocial challenges described by parents which were perceived as specific to parenting an autistic daughter, as opposed to a son. These included additional stress around having to advocate for their daughter, guilt over how they treated their daughter before her diagnosis, concern for their daughters’ futures and worries around their daughters’ vulnerability, particularly in sexual relationships. This was compounded by delayed diagnoses and lack of appropriate support from professionals. These parental pressures, stresses and worries appear to subsequently impact on their own wellbeing due to the effort required to behave in ways which they felt would help to protect their daughter. These unique challenges facing autistic girls and their families may help to explain higher levels of mental health difficulties in autistic women compared to autistic males and females without ASD (DaWalt et al., 2021).

The challenges of seeking a clinical diagnosis for a daughter with ASD were highlighted by parents across the studies. Two of the themes highlight this issue: ‘Autism is a male thing’ and ‘Nobody wanted to put a diagnosis on it’. The first theme acknowledges the lack of awareness and subsequent perceived stigma associated with the diagnosis for their daughters. Parents felt ASD is seen as a ‘male’ condition, and that others may not believe girls can have autism. They also highlighted that other parents or professionals expect to ‘see’ stereotypical presentations of autism. They felt this then led to others judging their parenting, particularly if their daughters’ symptoms were not outwardly visible.

The second theme considered diagnostic issues, with professionals struggling to diagnose their daughters. Both themes are consistent with previous research that suggests gendered social expectations and cultural norms may impact perceptions of how male and female autism presents (Kreiser & White, 2014). Participants often spoke about other diagnoses that were made in their efforts to seek an ASD diagnosis, such as ADHD and anxiety disorders. Comorbidity of mental health conditions in the context of autism is common in females, so it is likely these mental health diagnoses reflected a reality of their situations (Ottosen et al., 2019; Supekar et al., 2017; Uljarević et al., 2020). However, in some cases, parents felt this diagnosis resulted in a slower assessment process for ASD, or felt that professionals then dismissed the possibility of ASD in addition to the mental health condition. Research has also found that females with ASD can frequently be misdiagnosed (Green et al., 2019), so the experiences described may support the idea that services can struggle to detect ASD in females due to less ‘stereotypical’ or expected presentations. Thus, it may be that a higher proportion of females are autistic than is currently detected.

The findings on the unique experiences and presentations of girls with ASD also align with the body of literature that suggests that current assessment and diagnostic tools, such as the Autism Diagnostic Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al., 2012) and the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ; Baron-Cohen et al., 2001) and corresponding widely used diagnostic criteria, are likely to be insufficient to detect ASD in females (D'Mello et al., 2022; Kirkovski et al., 2013; Russell et al., 2021; Rynkiewicz et al., 2016). Existing diagnostic criteria and assessments are argued to be based on the male phenotype of autism, due to the disproportionate amount of research conducted with autistic males compared to females (D'Mello et al., 2022). This renders existing diagnostic tools as biased towards male presentations of ASD and thus insensitive to accurately detect the perhaps more subtle outwards presentations of autism in females (e.g. Rynkiewicz & Łucka, 2018). This is particularly thought to be the case for autistic females who have learnt to mask or camouflage their outwardly autistic traits or characteristics, leaving screening tools insensitive to these differences (Tubero-Fungueirino et al., 2021). Based on the findings of this review, it seems important for assessments of ASD in females to consider the possibility of ‘masking’ and any associated emotional consequences, whilst accepting there may be differences in presentation of ASD characteristics or presentations in different environments. This finding is supported by previous research, which finds gender differences in presentations in environments such as school, with females being less likely to present with behaviours considered typical of the profile of ASD (Hiller et al., 2014). Gendered expectations also contributed to the distress parents reported as they experienced delays in diagnosis, experienced others to be less understanding of their daughters’ difficulties, found it harder for their daughter to fit in and access appropriate support and expressed grief for life experiences they perceive their daughters will not experience, such as marriage or having children.

It is important to consider how many of the challenges identified by parents in these studies are specific to supporting a daughter with ASD as opposed to parental experiences of having any children with ASD, regardless of gender. The parental challenges identified in this systematic review are similar to those identified in a systematic review which did not distinguish between male and female experiences (Legg & Tickle, 2019). This previous review explored experiences of parents of boys and girls with ASD, highlighting issues such as struggling with emotions, including grief and self-blame (Legg & Tickle, 2019). They also identified issues around obtaining additional support and the lack of support post-diagnosis.

Despite these similarities, the current review suggests that there are some unique challenges experienced by parents of autistic girls which need to be considered. These include struggling to obtain the correct diagnosis or to find relevant information specific to girls’ presentations, needing additional support around puberty and menstruation and heightened concern around their daughters’ experiences of sex and relationships.

Strengths and Limitations

Whilst all studies included in the review were deemed to be of high quality based on the dimensions included in the CASP appraisal tool (2019), there are further limitations which need to be considered. It was decided that studies could be included where there was a ‘self-diagnosis’ of ASD within the female offspring, rather than purely those with a clinical diagnosis. This was decided due to the known difficulties females can experience in obtaining a timely diagnosis, as noted above. This only applied to one paper, in which two participants reported self-diagnosed ASD. However, this may limit conclusions which can be drawn as it is unknown whether these participants did in fact have ASD. The qualitative data included from the nine identified studies lacks insight from experiences of parents from a diverse range of backgrounds. More research is needed in relation to any potential impact of demographic variables on parents’ experiences when raising autistic females. These variables can include but are not limited to ethnicity, socioeconomic status, family structure and age. Additionally, participants were predominantly mothers, with only one study reporting to equally include both mothers and fathers. Furthermore, in the studies that did include fathers they did not include direct quotes that could be clearly identified as being from the fathers. Therefore, it is a significant omission that current research lacks insight into how fathers experience raising autistic daughters, and it remains to be seen whether more equal inclusion of fathers’ perspectives would impact the results found. It would be important to investigate this further as previous research has found fathers find it harder to cope with a child with ASD (Legg & Tickle, 2019). In addition, the daughters of the participants spanned a broad age range. This may influence the results as the age of the child and the life stage they are at during the time of the study may impact parental experiences. For example, parents of teenage daughters might be more likely to have concerns about romantic relationships or going to university compared to parents of younger girls. Future research could focus on the experience of parents of specific age groups for us to gain a better insight into parent experiences of autistic daughters across life stages, to create better tailored services and clinical guidelines for each developmental stage.

Future Directions

Based on the review findings, there are several clinical and research implications. The current diagnostic tools and criteria for ASD frequently cause a range of significant difficulties for autistic females and their families. The studies in the current review evidence how the whole family can be impacted by a lack of awareness of ASD presentations in females and delayed diagnosis. Mirroring suggestions made by the included studies, work needs to be done to develop the diagnostic criteria for girls with ASD, including the development of new diagnostic tools and processes. Gender-sensitive diagnostic tools could promote earlier detection of ASD in females. In addition, clinicians need to be aware of gender bias when using current ASD diagnostic tools. Increased training for clinical teams on ASD presentations in females could be helpful to improve awareness, which may reduce inaccurate assessments.

This systematic review also highlights some of the challenges and difficulties that females with autism can face, such as being misunderstood by professionals and struggling with relationships. It is understandable that this can contribute to psychological distress for both the girls with ASD themselves but also their families. Interventions specifically designed for girls with ASD that focus on developing social skills and self care have been met with success (e.g. Jamison & Schuttler, 2017). However, further development, research and evaluation into ASD support specifically for girls and their families would be beneficial as this was something many participants highlighted as lacking. Such interventions could be argued to be deficit-focused, by aiming to teach autistic girls to adhere to ‘social norms’ rather than allowing them to display their individuality.

In line with clinical guidelines in the UK (NICE, 2017), this review emphasizes the need for psychological support for parents of autistic daughters. The specific needs of this population need to be considered; this could include education on how autistic girls may typically present and how this can differ from autistic boys, advice around how to manage puberty and sexual relationships, reduce vulnerability to abuse, increase access to peer support groups and support to manage difficult emotions, such as grief or guilt.

It is important to note that this review also identified positive aspects of supporting a daughter with ASD, which has also been identified in previous research (e.g., Corman, 2009)—the idea that families can ‘come through the fog’. Some participants described the importance of recognising individual differences and that embracing their daughters’ differences can be helpful. Some reported close relationships with their daughters and acknowledged their positive character traits such as having a good moral compass and a logical attitude. Increasing awareness of these benefits of having a daughter with autism might help reduce stigma and help families identify their own strengths.

Parents also reported that they had increased confidence and understanding once they found out their daughter had ASD. This could be a key intervention component, as services can provide relevant information on how parents can support their daughter, as well as being encouraged to recognise when they have responded helpfully or advocated for their daughters.

Finally, it is important to recognise that not all individuals identify within the dichotomy of male or female. Research has suggested that there are high rates of gender variance in individuals with ASD, in particular females with ASD (Cooper et al., 2018). However, the research is limited and to the authors’ knowledge, there are no current studies investigating the experiences of parenting a child with ASD who does not identify within the dichotomy of male or female, or as a different gender to the one they were assigned at birth. As it has been recognised that different genders have different presentations and therefore need different diagnostic criteria, it needs to be ensured that diagnostic tools, processes and support are appropriate for those who do not identify as male or female, or if they identify as a different gender to the one they were assigned one at birth. This is important given the current review highlighted that a delayed diagnosis or inappropriate support has a subsequent impact on the wellbeing of the individual and the wider family. Thus, future research needs to explore these experiences further, so that gendered considerations in autistic individuals do not cause further harm to those already struggling within the current diagnostic systems.

Conclusions

The review found that parents of autistic daughters reported unique experiences, at times significantly impacting on their wellbeing. Parenting a female with ASD presents both benefits and challenges, which can be impacted by whether services recognise ASD in females and respond appropriately. More work can be done to increase awareness of ASD in females and provide a timely diagnosis and appropriate support. Further research is needed to identify the most effective methods to support parents of females with ASD. It is hoped that further research and awareness can positively influence the experiences of parents of autistic daughters and the females themselves.

References

Anderson, J., Marley, C., Gillespie-Smith, K., Carter, L., & MacMahon, K. (2020). When the mask comes off: Mothers’ experiences of parenting a daughter with autism spectrum condition. Autism, 24(6), 1546–1556.

Baldwin, S., & Costley, D. (2016). The experiences and needs of female adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(4), 483–495.

Bargiela, S., Steward, R., & Mandy, W. (2016). The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5–17.

Barroso, N. E., Mendez, L., Graziano, P. A., & Bagner, D. M. (2018). Parenting stress through the lens of different clinical groups: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 46(3), 449–461.

Cook, A., Ogden, J., & Winstone, N. (2018). Friendship motivations, challenges and the role of masking for girls with autism in contrasting school settings. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(3), 302–315.

Cooper, K., Smith, L. G., & Russell, A. J. (2018). Gender identity in autism: Sex differences in social affiliation with gender groups. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(12), 3995–4006.

Corman, M. K. (2009). The positives of caregiving: Mothers’ experiences caregiving for a child with autism. Families in Society, 90(4), 439–445.

Cridland, E. K., Jones, S. C., Caputi, P., & Magee, C. A. (2014). Being a girl in a boys’ world: Investigating the experiences of girls with autism spectrum disorders during adolescence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(6), 1261–1274.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme UK. (n.d.). CASP checklists: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

Croen, L. A., Zerbo, O., Qian, Y., Massolo, M. L., Rich, S., Sidney, S., & Kripke, C. (2015). The health status of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 19(7), 814–823.

Crouch, E., Radcliff, E., Brown, M., & Hung, P. (2019). Exploring the association between parenting stress and a child’s exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Children and youth services review, 102, 186–192.

Cummins, C., Pellicano, E., & Crane, L. (2020). Supporting minimally verbal autistic girls with intellectual disabilities through puberty: Perspectives of parents and educators. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 50(7), 2439–2448.

DaWalt, L. S., Taylor, J. L., Movaghar, A., Hong, J., Kim, B., Brilliant, M., & Mailick, M. R. (2021). Health profiles of adults with autism spectrum disorder: Differences between women and men. Autism Research, 14(9), 1896–1904.

Dike, J. E., DeLucia, E. A., Semones, O., Andrzejewski, T., & McDonnell, C. G. (2023). A systematic review of sexual violence amongst autistic individuals. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 10, 576–594.

D'Mello, A. M., Frosch, I. R., Li, C. E., Cardinaux, A. L., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2022). Exclusion of females in autism research: Empirical evidence for a “leaky” recruitment-to-research pipeline. Autism research: Official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 15(10), 1929–1940.

Elder, J. H., Kreider, C. M., Brasher, S. N., & Ansell, M. (2017). Clinical impact of early diagnosis of autism on the prognosis and parent–child relationships. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 283-292.

Erlandson, D. A., Harris, E. L., Skipper, B. L., & Allen, S. D. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry: A guide to methods. Sage.

Fernell, E., Eriksson, M. A., & Gillberg, C. (2013). Early diagnosis of autism and impact on prognosis: A narrative review. Clinical Epidemiology, 5, 33.

Fowler, K., & O’Connor, C. (2021). ‘I just rolled up my sleeves’: Mothers’ perspectives on raising girls on the autism spectrum. Autism, 25(1), 275–287.

Fuller, N., Iles, J., & Satherley, RM. (2021). The experience of raising girls with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review of qualitative research studies. PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews. CRD42021267393. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=267393

Gould, J., & Ashton-Smith, J. (2011). Missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis? Girls and women on the autism spectrum. Good Autism Practice (GAP), 12(1), 34–41.

Gray, L., Bownas, E., Hicks, L., Hutcheson-Galbraith, E., & Harrison, S. (2021). Towards a better understanding of girls on the Autism spectrum: Educational support and parental perspectives. Educational Psychology in Practice, 37(1), 74–93.

Green, R. M., Travers, A. M., Howe, Y., & McDougle, C. J. (2019). Women and autism spectrum disorder: Diagnosis and implications for treatment of adolescents and adults. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(4), 1–8.

Harrop, C., Jones, D., Zheng, S., Nowell, S., Boyd, B. A., & Sasson, N. (2018). Circumscribed interests and attention in autism: the role of biological sex. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 3449–3459.

Hayes, J., Ford, T., Rafeeque, H., & Russell, G. (2018). Clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in adults and children in the UK: A narrative review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–25.

Head, A. M., McGillivray, J. A., & Stokes, M. A. (2014). Gender differences in emotionality and sociability in children with autism spectrum disorders. Molecular Autism, 5(1), 1–9.

Hiller, R. M., Young, R. L., & Weber, N. (2016). Sex differences in pre-diagnosis concerns for children later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(1), 75–84.

Hiller, R. M., Young, R. L., & Weber, N. (2014). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder based on DSM-5 criteria: Evidence from clinician and teacher reporting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(8), 1381–1393.

Holtmann, M., Bölte, S., & Poustka, F. (2007). Autism spectrum disorders: Sex differences in autistic behaviour domains and coexisting psychopathology. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49(5), 361–366.

Hull, L., Petrides, K. V., & Mandy, W. (2020). The female autism phenotype and camouflaging: A narrative review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–12.

Jamison, T. R., & Schuttler, J. O. (2017). Overview and preliminary evidence for a social skills and self-care curriculum for adolescent females with autism: The girls night out model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(1), 110–125.

Jones, J. H., Call, T. A., Wolford, S. N., & McWey, L. M. (2021). Parental stress and child outcomes: The mediating role of family conflict. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(3), 746–756.

Kirkovski, M., Enticott, P. G., & Fitzgerald, P. B. (2013). A review of the role of female gender in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(11), 2584–2603.

Kreiser, N. L., & White, S. W. (2014). ASD in females: Are we overstating the gender difference in diagnosis? Clinical Child and Family Psychology review, 17(1), 67–84.

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., Auyeung, B., Chakrabarti, B., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Sex/gender differences and autism: Setting the scene for future research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(1), 11–24.

Lai, M. C., & Szatmari, P. (2020). Sex and gender impacts on the behavioural presentation and recognition of autism. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 33(2), 117–123.

Legg, H., & Tickle, A. (2019). UK parents’ experiences of their child receiving a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Autism, 23(8), 1897–1910.

Loomes, R., Hull, L., & Mandy, W. P. L. (2017). What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(6), 466–474.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavorne, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. L. (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) Manual (Part I): Modules 1-4. Western Psychological Services.

Mademtzi, M., Singh, P., Shic, F., & Koenig, K. (2018). Challenges of females with autism: A parental perspective. Journal of Autism and Developmental disorders, 48(4), 1301–1310.

McFayden, T. C., Albright, J., Muskett, A. E., & Scarpa, A. (2019). Brief report: Sex differences in ASD diagnosis—A brief report on restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(4), 1693–1699.

McCrossin, R. (2022). Finding the true number of females with autistic spectrum disorder by estimating the biases in initial recognition and clinical diagnosis. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 9(2), 272.

Milner, V., McIntosh, H., Colvert, E., & Happé, F. (2019). A qualitative exploration of the female experience of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(6), 2389–2402.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: Support and management. NICE guideline 170: https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG170

Navot, N., Jorgenson, A. G., & Webb, S. J. (2017). Maternal experience raising girls with autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative study. Child: Care, Health and Development, 43(4), 536–545.

Ooi, K. L., Ong, Y. S., Jacob, S. A., & Khan, T. M. (2016). A meta-synthesis on parenting a child with autism. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 745–762.

Ottosen, C., Larsen, J. T., Faraone, S. V., Chen, Q., Hartman, C., Larsson, H., et al. (2019). Sex differences in comorbidity patterns of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(4), 412–422.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, 71.

Potter, C. A. (2016). ‘I accept my son for who he is–he has incredible character and personality’: Fathers’ positive experiences of parenting children with autism. Disability & Society, 31(7), 948–965.

Rabbitte, K., Prendeville, P., & Kinsella, W. (2017). Parents’ experiences of the diagnostic process for girls with autism spectrum disorder in Ireland: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Educational and Child Psychology, 34(2), 54–66.

Robinson, E. B., Lichtenstein, P., Anckarsäter, H., Happé, F., & Ronald, A. (2013). Examining and interpreting the female protective effect against autistic behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(13), 5258–5262.

Russell, G., Stapley, S., Newlove-Delgado, T., Salmon, A., White, R., Warren, F., & Ford, T. (2021). Time trends in autism diagnosis over 20 years: A UK population-based cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(6), 674–682.

Rynkiewicz, A., & Łucka, I. (2018). Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in girls. Co-occurring psychopathology. Sex differences in clinical manifestation. Psychiatria Polska, 52(4), 629–639.

Rynkiewicz, A., Schuller, B., Marchi, E., Piana, S., Camurri, A., Lasalle, A., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2016). An investigation of the ‘female camouflage effect’ in autism using a computerized ADOS-2 and a test of sex/gender differences. Molecular Autism, 7, 10.

Sedgewick, F., Hill, V., & Pellicano, E. (2019). ‘It’s different for girls’: Gender differences in the friendships and conflict of autistic and neurotypical adolescents. Autism, 23(5), 1119–1132.

Smith, J. A., & Shinebourne, P. (2012). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. American Psychological Association.

Steward, R., Crane, L., Roy, E. M., Remington, A., & Pellicano, E. (2018). “Life is much more difficult to manage during periods”: Autistic experiences of menstruation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 4287–4292.

Supekar, K., Iyer, T., & Menon, V. (2017). The influence of sex and age on prevalence rates of comorbid conditions in autism. Autism Research, 10(5), 778–789.

Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology, 2, 17–37.

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 1–10.

Tint, A., Weiss, J. A., & Lunsky, Y. (2017). Identifying the clinical needs and patterns of health service use of adolescent girls and women with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 10(9), 1558–1566.

Tomeny, T. S. (2017). Parenting stress as an indirect pathway to mental health concerns among mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(7), 907–911.

Tubío-Fungueiriño, M., Cruz, S., Sampaio, A., Carracedo, A., & Fernandez-Prieto. (2021). Social camouflaging in females with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 2190–2199.

Uljarević, M., Hedley, D., Rose-Foley, K., Magiati, I., Cai, R. Y., Dissanayake, C., et al. (2020). Anxiety and depression from adolescence to old age in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(9), 3155–3165.

Watson, L., Hanna, P., & Jones, C. J. (2021). A systematic review of the experience of being a sibling of a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 26(3), 734–749.

World Health Organization. (2021). Autism spectrum disorders. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrum-disorders

Zamora, I., Harley, E. K., Green, S. A., Smith, K., & Kipke, M. D. (2014). How sex of children with autism spectrum disorders and access to treatment services relates to parental stress. Autism Research and Treatment, 2014, 1–5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hopkins, N., Iles, J. & Satherley, RM. The Experience of Raising Girls with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Systematic Review of Qualitative Research Studies. Rev J Autism Dev Disord (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-023-00419-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-023-00419-w