Abstract

Family caregivers often play a critical role in supporting their relative(s) with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) across the lifespan. This can lead to great burdens on family caregivers themselves. However, to date, the potential burden on family caregivers has not been in the focus of research, particularly, with respect to caregiver burden as relatives with ASD advance to adulthood. Thus, this scoping review aimed to (a) systematically map research regarding multiple dimensions of caregiver burden on family caregivers of adults with ASD (i.e., time dependence, developmental, physical, social, emotional, and financial burden) and (b) identify interventions designed to reduce such burden. A total of N = 33 eligible studies highlighted the impact of caregiving demands for adults with ASD, mainly focusing on emotional burden of caregiving (n = 27), reporting decreased mental quality of life and mental health. Findings gave indications on all other dimensions of caregiver burden, but evidence is lacking. No study was identified that provided evidence for specific interventions to reduce or to prevent caregiver burden. Findings highlighted the urgent need for more research on this topic and the development of strategies to support family caregivers of adults with ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Caregivers within families play an important role in supporting their relative(s) with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) across the lifespan. Although caring for a loved one might have positive influences on family functioning (Beighton & Wills, 2017; Phelps et al., 2009; Sarriá & Pozo, 2015), it can also be associated with numerous impacts and burdens on the lives of family caregivers of individuals with ASD (Hoefman et al., 2013; Marsack & Hopp, 2018; Sonido et al., 2022; Tint & Weiss, 2016). To date, research primarily focused on parental caregivers of children with ASD (Bonis & Sawin, 2016; Bromley et al., 2004; Davy et al., 2022; Safe et al., 2012), but the perspective of family caregivers of adults with ASD is gaining importance (Hare et al., 2004; Liao & Lin, 2013). This is essential, as ASD is a lifelong condition and impairments are pervasive across the lifespan. However, little is known about the specific challenges of caring for adult relatives with ASD and how this might affect family caregivers (Cridland et al., 2014). Thus, a better understanding of the burden of family caregivers would “promote the well-being of families, which in turn will contribute to fostering democratic, stable and cohesive societies” (United Nations, 2012, p. 2).

Caregiving Demands of Adults with ASD

The core symptoms of ASD include persistent impairments in social communication/interactions and restrictive, repetitive, and inflexible patterns of behavior, interests, or activities (American Psychiatric Association 2013; American Psychiatric Association 2022). Additionally, challenging behaviors (e.g., self-injury, suicide attempts, and aggression) and comorbid somatic and mental disorders are common (Croen et al., 2015; Vohra et al., 2017). One-third to one-half of individuals with ASD have an accompanying intellectual disability (ID; Maenner et al., 2020; Postorino et al., 2016). The nature of these symptoms usually leads to distinct challenges in caring for an individual with ASD, such as the need for mediation in social interactions, inflexible daily routines, lack of spontaneity, or inappropriate behaviors (Cadman et al., 2012; Cridland et al., 2014). Furthermore, a lot of individuals with ASD require informal care and assistance with personal care (e.g., dressing, toileting, meals), providing transport, general housework, and/or emotional support (Järbrink et al., 2003). As there are only very few services available that support individuals with ASD in adulthood (Lord et al., 2022; Nicolaidis et al., 2015), many adults with ASD rely on support by their families (Cadman et al., 2012). For example, the majority of adults with ASD remain co-residing with their parents well into their late 20s, irrespective of the presence of a comorbid ID (Levy & Perry, 2011; Roux et al., 2015).

Caregiver Burden

Previous research defined caregiver burden as a relative’s appraisal of stressors and challenges related to the provision of care (Novak & Guest, 1989). Novak and Guest (1989), who primarily focused their research on caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, defined five dimensions of caregiver burden. First, time dependence burden includes restrictions on the caregiver’s time available for personal interests and activities (Altiere & von Kluge, 2009; Smith et al., 2010) or privacy (Marsack & Perry, 2018). Second, developmental burden refers to personal or social underdevelopment compared to peers who do not have a relative who requires care (Novak & Guest, 1989), which can lead to feelings of isolation and a perception of being disconnected or detached from the social environment (Hare et al., 2004; Hines et al., 2014; Marsack & Hopp, 2018). Third, physical burden describes caregivers’ feelings of chronic fatigue and damage to physical health (Novak & Guest, 1989). Fourth, social burden comprise feelings of role conflicts, as well as limited time and energy that they can invest in relationships or in occupational participation (Novak & Guest, 1989). Fifth, emotional burden refers to negative feelings towards the relative with ASD (Novak & Guest, 1989), such as guilt and blame (Marsack & Hopp, 2018; Marsack-Topolewski & Graves, 2019). In extension to this initial definition by Novak and Guest (1989), prior research reported caregiving to also worsen family caregivers’ mental health, including higher levels of psychological distress (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Blacher & McIntyre, 2006), and higher prevalence’s of mental disorders (Magallon-Neri et al., 2018; Schnabel et al., 2020).

In addition to these dimensions of caregiver burden by Novak and Guest (1989), Marsack and Hopp (2018), who investigated parental caregivers of adults with ASD, added the financial burden. This burden includes effects of caring on financial resources, such as direct costs related to specialized therapies and indirect costs related to constrains on working life (Cidav et al., 2012; DePape & Lindsay, 2015; Marsack & Perry, 2018).

To date, no comprehensive overview of burdens on family caregivers of adults with ASD was published. Existing reviews either focused on ASD in childhood (Tint & Weiss, 2016) or only assessed mental well-being of family caregivers (Sonido et al., 2019). Therefore, this scoping review aims to provide an overview of research on the abovementioned dimensions of burden on family caregivers of adults with ASD (i.e., time dependence, developmental, physical, social, emotional, and financial burden), to identify previously published interventions or supporting services designed to reduce such burden, and to detect existing knowledge gaps for further research. Thus, the following research questions were formulated: (a) What is known about the time dependence, developmental, social, physical, emotional, and financial burden on family caregivers of adults with ASD? (b) Which interventions exist to reduce caregiver burden on family caregivers of adults with ASD?

Method

This scoping review is based on the framework for scoping reviews by Arksey and O'Malley (2005), and conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018). A scoping review protocol was developed a priori, which was not preregistered.

Eligibility Criteria

This scoping review includes different types of peer-reviewed publications (quantitative, qualitative, mixed-method studies, and reviews). The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) publications written in English or German; (2) target population was either first- or second-degree family members (including partners/spouses); (3) of adult relatives (18+ years); (4) with secured ASD diagnosis; and (5) results included indications of caregiver burden and/or interventions to reduce caregiver burden.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was performed in the databases PubMed and EBSCOhost between June 2022 and January 2023. Publication year was not restricted. The reference and citation lists of included studies were used to locate additional eligible studies. See Table S1 for full search terms.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

After removing duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened. Studies including participants with unspecific diagnostic groups (e.g., individuals with unspecific developmental and/or intellectual disabilities) or undefined range of age were excluded to provide a homogenous evidence base. Remaining studies were screened for eligibility in full by first author (S.D.) and a trained student research assistant. Screening resulted in 93% agreement rate for a randomly selected data sample (20% of all publications). Disagreements were clarified through consented discussion.

A data extraction sheet was developed, which contained the following data items: (1) title; (2) author(s); (3) year of publication; (4) country of origin; (5) study design, method; and data analysis; (6) eligibility criteria; (7) sample characteristics of caregivers and care recipients; and (8) results and original authors’ interpretation. S.D. and a trained student research assistant extracted the data from all included papers. Results were categorized into the six dimensions of caregiver burden (time dependence, developmental, physical, social, emotional, and financial burden) based on the definitions by Novak and Guest (1989) and Marsack and Hopp (2018). An overview of the burden definitions used in previous research and in the current scoping review is shown in Table S2. Some studies reported data without differentiating between the dimensions of caregiver burden, which is presented as caregiver burden composite in the “Results” section. For results with overlapping contents, burden-specific categorization was discussed with the last author (J.P.) until consensus was reached. Results over studies were synthesized by the first author and were reported according to each dimension of caregiver burden.

Results

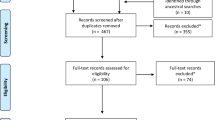

A total of 33 articles were included in the scoping review. For details, see the flowchart of the study selection process (Fig. 1). The 33 studies consisted of 17 quantitative, eight qualitative, and three mixed methods studies, as well as five literature reviews (see Table 2 in Appendix I). Most studies were conducted in the USA (55.9%), followed by the UK (23.5%; see Table 1). The majority of family caregivers of adults with ASD were parents (in 58.1% of studies), and the most investigated burden was the emotional burden (34.6% of studies; see Fig. 2). The caregivers’ age ranged from 18 to 87 years, and investigated caregivers were predominantly female (58.4–100%). The care recipients’ age ranged from 18 to 96 years, and, except for one study, the majority of adults with ASD were male. Six studies investigated caregivers of adults with ASD and comorbid ID.

Dimensions of Burden on Family Caregivers of Adults with ASD

All dimensions of burden were detected within the included studies on family caregivers of adults with ASD. However, the amount of available research data differed. For an overview, see Fig. 2. In the following sections, detailed results are presented according to individual dimensions of burden. No evidence on interventions to reduce or prevent caregiver burden was identified.

Time Dependence Burden

In total, 11 studies provided evidence on time dependence burden (for details, see Table 2 in Appendix I). Except for one study, all participants were parents. All quantitative studies (n = 4;Marsack & Hopp, 2018; Marsack-Topolewski, 2021; Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021; Marsack-Topolewski & Wang, 2022) measured time dependence burden with the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI; Novak & Guest, 1989). Studies found an increased CBI mean score for the subscale “time dependence burden,” indicating that parental caregivers experienced strain due to caring for the adult family members with ASD on a descriptive level (Marsack-Topolewski, 2021; Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021; Marsack-Topolewski & Wang, 2022; Marsack & Hopp, 2018). Moreover, parents who provided care to at least one adult child with ASD and another care recipient (compound caregivers) had significantly higher levels of time dependence burden than parents who only provided care for an adult child with ASD (noncompound caregivers; Marsack-Topolewski, 2021). A higher functional level or increased independence with respect to daily living skills in adult relatives with ASD was associated with less time dependence burden in parental caregivers (Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021). However, the time dependence burden was found to be no significant predictor of parental quality of life (QoL) (Marsack-Topolewski & Church, 2019).

Qualitative studies (n = 5) provided deeper insights on causes and effects as well as subjective relevance of time dependence burden (Hare et al., 2004; Hines et al., 2014; Marsack & Perry, 2018; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020; Tozer & Atkin, 2015). Parents stated that they “navigate the 24/7 needs” of their adult children with ASD (Marsack & Perry, 2018, p. 545), and reported a substantial impact on their daily routines (Hines et al., 2014; Marsack & Perry, 2018) in several respects including lack of spontaneity and flexibility (Hines et al., 2014), and reduced privacy and time for themselves (Marsack & Perry, 2018; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020). Supported living for the adult child with ASD had positive effects such as more free time and freedom for the parents (Krauss et al., 2005). One study by Tozer and Atkin (2015) investigated siblings of adults with ASD and reported difficulties to spent time with their own commitments (e.g., spouses/partners, children, friends, parents, or work) and their sibling with ASD, to balance demands, and presence of a constant tension and feelings of guilt.

Developmental Burden

In total, 11 studies reported on developmental burden and all investigated parental caregivers of adult children with ASD. All quantitative studies (n = 4; Marsack-Topolewski, 2021; Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021; Marsack-Topolewski & Wang, 2022; Marsack & Hopp, 2018) detected developmental burden in parental caregivers, assessed with the CBI (Novak & Guest, 1989). Developmental burden was significantly higher when adults with ASD were more dependent in completing activities of daily living, as well as in compound caregivers (Marsack-Topolewski, 2021; Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021; Marsack-Topolewski & Wang, 2022). It was assumed that parents who were less involved in assisting were more likely to find the time to engage in other social roles that would decrease their developmental burden (Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021).

Qualitative studies (n = 5) discussed potential reasons for developmental burden with focus on the balancing fulfillment of own needs and providing care for the adult relative with ASD (Griffith et al., 2012; Hare et al., 2004; Hines et al., 2014; Marsack & Perry, 2018; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020). Parental caregivers reported restrictions on their lives and social exclusion, leading to feelings of isolation (Hare et al., 2004) and negative comparisons with peers (Marsack & Perry, 2018). Two main reasons for social exclusion were identified: First, caregiving demands caused the social network to shrink (Hare et al., 2004; Hines et al., 2014; Marsack & Perry, 2018; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020). Second, misunderstandings and stigma about ASD led to social exclusion (Griffith et al., 2012; Marsack & Perry, 2018; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020). The hidden nature of ASD and a lack of visible physical markers of disability may lead to the perception to be non-autistic (Griffith et al., 2012; Marsack & Perry, 2018). Parents felt that their caregiving demands were neither understood nor appreciated by the general public, leading to this sense of isolation (Griffith et al., 2012).

One mixed methods study by Krauss et al. (2005) found that one-fifth of the investigated parents reported social isolation to be a negative aspect of cohabiting with an adult child with ASD. Another mixed-method study by Marsack-Topolewski and Church (2019) found that the developmental burden (besides investigated time dependence, emotional, and financial burden) was the strongest predictor of the parental mental QoL, demonstrating an inverse relationship.

Physical Burden

Three studies (investigating siblings, parents, or especially mothers) provided indications for physical burden on family caregivers of adults with ASD. One quantitative study reported decreased general health in siblings of adults with ASD compared to siblings of adults with Down Syndrome (Hodapp & Urbano, 2007).

Qualitative data revealed that parents developed protracted physical illnesses and suggested it was caused by long-term stress and worry related to the care of their child with ASD (Oti-Boadi et al., 2020).

A mixed-method study found that living together with the adult child with ASD is related with stress and fatigue (Krauss et al., 2005).

Social Burden

The social burden was studied in one quantitative, five qualitative, and one mixed-method study, investigating siblings and parents. Quantitative data revealed that siblings of adults with ASD reported a stronger impact on their relationship with the parents compared to siblings of adults with Down Syndrome (Orsmond & Seltzer, 2007).

All qualitative studies (n = 5) interviewed parental caregivers and found a negative impact of continuous care on other relationships and social activities (Hare et al., 2004; Hines et al., 2014; Marsack & Perry, 2018; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020; Tozer & Atkin, 2015). Parents discussed the potential threat of a crisis in their child’s life and a lack of adequate respite care impacting their own social and recreational opportunities (Hines et al., 2014). This applied to friendships as well as to relationships within the families (Marsack & Perry, 2018; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020). For example, the feeling of not knowing the own partner/spouse anymore (Hare et al., 2004) or lack of time for other children without ASD (Hare et al., 2004; Marsack & Perry, 2018) were described because the majority of the time was spend caring for the adult family member with ASD. This was assumed as possible reasons why some families took the adult child with ASD into care (Hare et al., 2004). Furthermore, one study identified disruptions in the professional careers of maternal caregivers, as they could not combine work and care for the adult child with ASD (Oti-Boadi et al., 2020).

A mixed-method study explored positive and negative aspects of adult children with ASD living at home or in care, revealing that the living situation influences the social and work life (Krauss et al., 2005).

Emotional Burden

In total, 27 studies provided evidence on the emotional burden of caregiving in family caregivers of adults with ASD. Of these studies, 11 studies provided evidence on negative feelings or relationships towards the adult with ASD according to the definition of Novak and Guest (1989) (see Table S2). In addition, 22 studies gave evidence on influences on the mental QoL or the development of mental disorders in family caregivers.

Negative Feelings/Relationships

Quantitative studies (n = 6; Hodapp & Urbano, 2007; Marsack-Topolewski, 2021; Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021; Marsack-Topolewski & Wang, 2022; Marsack & Hopp, 2018; Orsmond & Seltzer, 2007) utilized either the CBI (Novak & Guest, 1989) to investigate parents (n = 3) or the positive affect index of relationship quality (Bengston & Black, 1973) to investigate siblings (n = 2). Studies in parents revealed no emotional burden (Marsack & Hopp, 2018) or only slightly increased scores on a descriptive level (Marsack-Topolewski, 2021; Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021). Research comparing the relationship quality of siblings of adults with ASD to siblings of adults with Down Syndrome showed that the latter felt like more respectful and fair towards their sibling (Hodapp & Urbano, 2007) and reported significantly higher levels of positive affect in their relationship than siblings of adults with ASD (Orsmond & Seltzer, 2007).

Qualitative studies (n = 4) investigated parents (n = 2), spouses (n = 1), and siblings (n = 1), and indicated an often conflictual relationship towards the adult with ASD, irrespective of the relationship (Hines et al., 2014; Lewis, 2017; Marsack & Perry, 2018; Tozer & Atkin, 2015).

A mixed-method study found that emotional burden did not predict parental QoL (Marsack-Topolewski & Church, 2019).

Influences on Mental QoL/Mental Disorders

Quantitative studies (n = 12) investigated parents (n = 5; Barker et al., 2011; Lee & Shivers, 2019; Marsack-Topolewski, 2020; Marsack & Samuel, 2017; Rattaz et al., 2017), siblings (n = 3; Hodapp & Urbano, 2007; Orsmond & Seltzer, 2007; Tomeny et al., 2017), or mixed family caregivers of adults with ASD (n = 4; Grootscholten et al., 2018; Herrema et al., 2017a, 2017b; Sonido et al., 2022). Several studies found higher levels of depressive symptoms and anxiety, and lower QoL in caregivers of adult family members with ASD (e.g. Barker et al., 2011; Grootscholten et al., 2018; Lee & Shivers, 2019). Across a 10-year period, depressive symptoms in caregivers remained constant, whereas anxiety decreased, and behavior problems of the care recipient correlated positively with depressive and anxiety symptoms (Barker et al., 2011).

Studies on caregivers’ mental QoL revealed a number of predictors based on caregiver variables (e.g., age, intolerance of uncertainty, unpreparedness for the future) and care-recipient variables (e.g., ID, mental comorbidities, adaptive skills, symptom severity) (Herrema et al., 2017b; Rattaz et al., 2017; Sonido et al., 2022). The care recipients’ age and the utilization of formal social support revealed no significant relation to caregivers’ QoL (Lee & Shivers, 2019; Marsack & Samuel, 2017). One study reported that depressive behaviors of care recipients mediated the relationship between caregiver burden and mental QoL (Sonido et al., 2022). Lower levels of QoL were reported for compound caregivers compared to noncompound caregivers (Marsack-Topolewski, 2020). Grootscholten et al. (2018) found higher emotional distress in caregivers of adults with ASD compared to caregivers of adults with schizophrenia. Furthermore, caregivers of adults with ASD frequently expressed concerns, worries, and anxiety about the future and potential support (Herrema et al., 2017a). Findings by Sonido et al. (2022) identified caregiver coping and cognitive dispositions as a predictor for caregiver mental well-being. Studies assessing siblings of adults with ASD found that parent-focused parentification was positively correlated with anxiety and stress in these siblings (Tomeny et al., 2017), and that they experienced higher levels of depressive symptoms compared to siblings of individuals with Down Syndrome (Hodapp & Urbano, 2007; Orsmond & Seltzer, 2007).

Qualitative studies (n = 8) investigated burden on mental health in parents (n = 6; e.g., Griffith et al., 2012; Hare et al., 2004; Hines et al., 2014), siblings (n = 1; Tozer & Atkin, 2015), and spouses of adults with ASD (n = 1; Lewis, 2017). In line with the quantitative results, parents reported high levels of psychological distress, anxiety, and worries about the future (e.g., Griffith et al., 2012; Marsack-Topolewski & Graves, 2019; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020). Furthermore, the strain on marriage (possibly leading to divorce), other children, and the family unit as a whole, directly attributed to having a child with ASD, were discussed as emotionally burdening (Hines et al., 2014). Parental mental health was reported to decrease due to lack of service provision, lack of knowledge in healthcare providers, maintaining emotional balance for the family, and care recipients’ inappropriate behaviors (e.g., Griffith et al., 2012; Hines et al., 2014; Marsack & Perry, 2018).

One qualitative study on siblings of adults with ASD reflected on difficulties growing up with someone who has ASD, unresolved emotional issues, and resentments about the past. Most siblings expressed sadness and frustration about the limited reciprocity in their relationship, including a sense of loss because they did not have a typical reciprocal sibling relationship and rather felt the need to protect the sibling with ASD (Tozer & Atkin, 2015). In line with other caregivers, partners/spouses reported worries about the future and unmet emotional needs (Lewis, 2017). However, they reported the lack of intimacy/sex and shifted relationship roles due to the ASD of their partner/spouse as emotionally distressing (Lewis, 2017).

A mixed-method study by Krauss et al. (2005) investigated the impact of housing situations on maternal emotional burden. They reported positive aspects of living together with the child (e.g., peace of mind, shared love) and several negative aspects (stress, negative impact on siblings, worries about the future) affecting mental health. Positive aspects of children living outside the home (e.g., better marriage, benefits to other children) and negative aspects (e.g., feelings of guilt/worries/concerns, missing of child) were reported, too.

A systematic review by Sonido et al. (2019) on mental well-being of caregivers of adults with ASD differentiated contributors to carer stress and carer resources. Carer stress based on the previously mentioned care-recipient-related factors and carer-related contributors to stress. Potential carer resources included higher socioeconomic status, age, education, number of children, informal support received, marital status and support, caring relationship, perceptions of ASD, and optimism.

Financial Burden

In total, 12 studies reported evidence on financial burden in parental caregivers of adults with ASD. Quantitative studies (n = 5) reported financial burden (Marsack & Hopp, 2018; Marsack-Topolewski, 2021; Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021; Marsack-Topolewski & Church, 2019; Marsack-Topolewski & Wang, 2022), always assessed with the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA; Given et al., 1992). Two studies reported that financial burden was significantly higher in noncompound caregivers than in compound caregivers (Marsack-Topolewski, 2021; Marsack-Topolewski & Wang, 2022). One study found a weak significant association between the adult child’s dependence level and parental financial burden (Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021). The authors suggested that other factors (e.g., availability of medical insurance, discretionary income to pay for out-of-pocket services) are likely to have a stronger influence on the financial burden than the adult child’s dependence in the activities of daily living (Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021). Financial burden was not a predictor of parental QoL (Marsack-Topolewski & Church, 2019).

All qualitative studies (n = 3) reported loss of employment and high costs for care as potential sources of financial burden in parents (Hare et al., 2004;Marsack & Perry, 2018 ; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020). Two studies reported associations between difficulties to combine work with care, which led to unemployment and negative effects on the financial situation (Marsack & Perry, 2018; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020). In addition, increased need for money to finance care for their adult child was reported (Hare et al., 2004; Oti-Boadi et al., 2020).

Reviews (n = 4) found evidence that costs of informal care and productivity loss were substantial in caregivers and substantiated a large part of overall costs related to ASD in the USA and the UK (Buescher et al., 2014; Ganz, 2007; Knapp et al., 2009; Rogge & Janssen, 2019). Absence of comorbid ID increased costs for parents of adults with ASD (Buescher et al., 2014; Knapp et al., 2009; Rogge & Janssen, 2019).

Caregiver Burden (Composite)

Six studies (five quantitative and one mixed methods study) assessed four of the caregiver burden dimensions (time dependence, developmental, emotional, and financial burden) as a composite score (without differentiation between the four dimensions) in parental caregivers. Burden were measured with the CBI (Novak & Guest, 1989), the CRA (Given et al., 1992), or caregiver burden (Heller et al., 1994). Studies showed increased composite scores for caregiver burden in family caregivers of adults with ASD (Marsack-Topolewski, 2021). In addition, they provided evidence on factors influencing the intensity of burden of caregivers. Studies reported that care recipients’ health, level of maladaptive behavior, degree of independence in activities of daily living, presence of comorbid ID, and availability of informal support were related to total caregiver burden, and partially mediated the relationship between caregiver burden and parental QoL (Burke & Heller, 2016; Marsack & Hopp, 2018; Marsack & Samuel, 2017; Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021; Marsack-Topolewski & Maragakis, 2020). Marsack-Topolewski and Wang (2022) showed significant correlations between the four dimensions of caregiver burden, with the strongest correlations between the emotional and the developmental burden, and the time dependence and developmental burden.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to investigate and summarize the existing literature on dimensions of burden in family caregivers of adults with ASD, thereby scrutinizing the exact nature, relevance, and potentially influencing factors of specific burdens. In total, 33 studies provided evidence on all six dimensions of burden (time dependence, developmental, social, physical, emotional, and financial) or a composite score. No study was identified that provided evidence on interventions or suggestions for services tailored for family caregivers of adults with ASD.

Emotional burden was the most prominent dimension, with a focus on the impact of caregiving on family caregivers’ mental health. Several care-recipient-related and carer-related variables influencing caregivers’ mental health were identified. Thus, findings suggest that the expansion of the original emotional burden definition (Novak & Guest, 1989) by including these aspects like low-threshold symptoms of mental disorders and/or QoL is justified. These aspects also play a significant role in family caregivers of individuals with other chronic diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (Pinyopornpanish et al., 2021), schizophrenia, and bipolar disorders (Karambelas et al., 2022), and should be considered in future research.

To date, all other dimensions of caregiver burden have been less thoroughly investigated both in caregivers of adults with ASD and in caregivers of other disorders, e.g., schizophrenia (Awad & Voruganti, 2008), presumably resulting from mental health being the most extensively studied and operationalized area in research compared to the other dimensions of caregiver burden. Findings indicate the presence of all dimensions but evidence remains insufficient. Especially the presence of the social and physical burden could not be conclusively clarified as qualitative findings suggest family caregivers suffer from these burdens but quantitative evidence is lacking. However, findings of all dimensions supported the assumption that, for example, the residential situation, the level of independence of the adult with ASD, and the presence of informal and formal support might have potential to reduce the intensity of caregiver burden cross-dimensional.

Some relations between the dimensions of caregiver burden have been analyzed. One study examined influences of the time dependence, developmental, emotional, and financial burden on the parental mental QoL (Marsack-Topolewski & Church, 2019). Findings of these study found that the developmental burden strongly predicts the parental mental QoL, but the reasons for this remains unclear. While the developmental burden has been studied in other research fields (e.g., dementia), there has been less in-depth research in the area of ASD (Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021). Therefore, developmental burden needs to become a scientific focus. However, to date, the relationship between the other dimensions of caregiver burden has not been investigated, but it can be assumed that, for example, social burden is influencing emotional burden, as it is closely related to mental QoL (Beierlein et al., 2012).

With respect to the second research aim, no intervention study was included in the scoping review. However, it can be assumed that corresponding services for family caregivers of adults with ASD exist (e.g., self-help groups) that have not yet been empirically investigated. Clinically, most health care systems are organized to meet the needs of the individuals with ASD; the needs of family caregivers are rarely addressed (Karst & Van Hecke, 2012). Services could be potentially effective, particularly with regard to the emotional burden, as results from intervention studies on caregivers of children with ASD or Alzheimer’s disease showed, for example, decreased depressive and anxiety symptoms and improvements in QoL (Beinart et al., 2012; Bekhet, 2017; Smith et al., 2010). Furthermore, some of the included studies indicated that caregivers demanded interventions to reduce caregiver burden (e.g. Grootscholten et al., 2018; Hare et al., 2004; Lewis, 2017).

In sum, the results reveal missing evidence on several aspects: (a) influencing factors of the specific burdens; (b) relationships between different dimensions of burden and potential dependencies; (c) associations between presence of burden and well-being of caregivers and other family members; (d) potential interactions between caregivers well-being and care recipients well-being; and (e) interventions/services to prevent and/or to reduce specific burden.

Limitations and Future Research

First, this review is limited in mapping all possible perspectives on caregiver burden in adults with ASD. There is a low ratio of participating fathers, reflecting the difficulty of recruiting fathers for autism research studies (Johnson & Simpson, 2013). Maternal perspectives are important but may not necessarily reflect those of other family members (Cridland et al., 2014). It is assumed that fathers either might not have time to participate or might not be involved into caregiving due to the traditional role of maternal parenting (Smith et al., 2010). Siblings and partners/spouses were barely examined so far, although the findings indicated that they also experience multiple caregiver burden. Furthermore, the identified studies were assessed in mostly high-income countries and, hence, do not account for additional challenges faced by families in low- and middle-income countries who may experience limited access to supports. It remains unclear whether the inclusion of other perspectives may have been associated with different emphasis of specific burdens on caregivers in adult ASD. Additional research is needed to illustrate multiple perspectives and address cultural impact on caregiver burden in ASD.

Second, quantitative data was often collected with the CBI (Novak & Guest, 1989), a questionnaire developed for caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. It remains unclear whether the CBI adequately applies to the burdens of caregivers in ASD. In addition, some dimensions appeared to be overlapping and should therefore be examined for discriminatory power.

Third, similarities in sample size and sociodemographic variables have been registered, giving reason to believe that data from the same sample may have been included in several publications, which must be taken into account in order to ensure the representativeness of the results of this scoping review (Marsack & Hopp, 2018; Marsack & Samuel, 2017; Marsack-Topolewski, 2020; Marsack-Topolewski, 2021; Marsack-Topolewski et al., 2021; Marsack-Topolewski & Church, 2019; Marsack-Topolewski & Maragakis, 2020; Marsack-Topolewski & Wang, 2022).

Lastly, reported findings were often secondary results, i.e., not the focus of the original research, and therefore might not provide a comprehensive picture. Future research should aim to combine longitudinal quantitative and qualitative data from heterogeneous samples to enable an increased focus on the dimensions of caregiver burden. A better understanding of the origin and relationship between dimensions of burden should be the priority of future research in this field. Based on this, the development and evaluation of services for family caregivers of adults with ASD should represent a long-term goal. The focus should not only include the treatment of manifest mental disorders, but also the prevention of perceived caregiver burden and the maintenance of mental health. Furthermore, there is a need to provide adequate healthcare for adults with ASD, which could also relieve the burdens on family caregivers. Future research should try to shed more light on these topics since they might be a key to improve the life of family caregivers of adults with ASD.

Conclusion

Based on our analysis, this is the first scoping review that gives a comprehensive overview on existing literature about different dimensions of burden (time dependence, developmental, social, physical, emotional, financial) on family caregivers of adults with ASD. Indications for all dimensions of caregiver burden were detected, highlighting the emotional burden on family caregivers with focus on family caregivers’ mental well-being. Accordingly, potential factors of influence were reported (e.g., carer and care recipient related variables). However, evidence on all other dimensions of caregiver burden was partially lacking or conflicting. Despite the cross-dimensional burden and impact of caregiving, no interventions to address specific or overall burden in family caregivers of adults with ASD were identified in the literature. Although concerns of family caregivers are increasingly addressed in autism research, there is still a lack of comprehensive, in-depth evidence regarding the underlying mechanisms, interactions, and time course of the different dimensions of caregiver burden. Further research on all dimensions of caregiver burden is required to develop tailored services to reduce burden on family caregivers of adults with ASD.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ASD:

-

Autism spectrum disorder

- CBI:

-

Caregiver Burden Inventory (Novak & Guest, 1989)

- CRA:

-

Caregiver Reaction Assessment (Given et al., 1992)

- DASS-21:

-

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995)

- ID:

-

Intellectual disability

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- WHOQOL-BREF:

-

World Health Organization Quality of Life—abbreviated version (World Health Organization, 1996)

References

Abbeduto, L., Seltzer, M. M., Shattuck, P., Krauss, M. W., Orsmond, G. I., & Murphy, M. (2004). Psychological Well-Being and Coping in Mothers of Youths With Autism, Down Syndrome, or Fragile X Syndrome. Merican Journal on Mental Retardation, 109(3), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109/3C237:pwacim/3E2.0.co;2

Altiere, M. J., & von Kluge, S. (2009, Jun). Searching for acceptance: challenges encountered while raising a child with autism. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34(2), 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250902845202

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). Text Revision American Psychiatric Publishing.

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Awad, A. G., & Voruganti, L. N. P. (2008). The Burden of Schizophrenia on Caregivers. PharmacoEconomics, 26(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200826020-00005

Baghdadli, A., Pry, R., Michelon, C., & Rattaz, C. (2014, Aug). Impact of autism in adolescents on parental quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 23(6), 1859–1868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0635-6

Barker, E. T., Hartley, S. L., Seltzer, M. M., Floyd, F. J., Greenberg, J. S., & Orsmond, G. I. (2011). Trajectories of emotional well-being in mothers of adolescents and adults with autism. Developmental Psychology, 47(2), 551–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021268

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 5–17.

Beierlein, V., Morfeld, M., Bergelt, C., Bullinger, M., & Brähler, E. (2012). Messung der gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität mit dem SF-8. Diagnostica, 58(3), 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000068

Beighton, C., & Wills, J. (2017, Dec). Are parents identifying positive aspects to parenting their child with an intellectual disability or are they just coping? A qualitative exploration. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 21(4), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629516656073

Beinart, N., Weinman, J., Wade, D., & Brady, R. (2012, Jan). Caregiver burden and psychoeducational interventions in Alzheimer's disease: a review. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra, 2(1), 638–648. https://doi.org/10.1159/000345777

Bekhet, A. K. (2017). Positive thinking training intervention for caregivers of persons with autism: Establishing fidelity. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 31(3), 306–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2017.02.006

Bengston, V. L., & Black, K. D. (1973). Intergenerational relations and continuities in socialization. In P. B. W. Schaie (Ed.), Life-Span Development Psychology: Personality and Socialization (pp. 207–234). Academic Press.

Blacher, J., & McIntyre, L. L. (2006). Syndrome specificity and behavioural disorders in young adults with intellectual disability: cultural differences in family impact. Journal of intellectual disability research : JIDR, 50(Pt 3), 184–198.

Bonis, S. A., & Sawin, K. J. (2016). Risks and Protective Factors for Stress Self-Management in Parents of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Integrated Review of the Literature. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 31(6), 567–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2016.08.006

Brannan, A. M., Heflinger, C. A., & Bickman, L. (1997). The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire:Measuring the Impact on the Family of Living with a Child with Serious Emotional Disturbance. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 5(4), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/106342669700500404

Bromley, J., Hare, D. J., Davison, K., & Emerson, E. (2004). Mothers supporting children with autistic spectrum disorders: Social support, mental health status and satisfaction with services. AUTISM, 8(4), 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361304047224

Buescher, A. V., Cidav, Z., Knapp, M., & Mandell, D. S. (2014). Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(8), 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210

Burke, M., & Heller, T. (2016). Individual, parent and social-environmental correlates of caregiving experiences among parents of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 60(5), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12271

Cadman, T., Eklund, H., Howley, D., Hayward, H., Clarke, H., Findon, J., Xenitidis, K., Murphy, D., Asherson, P., & Glaser, K. (2012, Sep). Caregiver burden as people with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder transition into adolescence and adulthood in the United Kingdom. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(9), 879–888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.06.017

Carleton, R., Sharpe, D., & Asmundson, G. .J. .G. (2007). Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty: Requisites of the fundamental fears? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(10), 2307–2316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.006

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1070-5503), 92–100.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

Cidav, Z., Marcus, S. C., & Mandell, D. S. (2012). Implications of childhood autism for parental employment and earnings. Pediatrics, 129(4), 617–623. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2700

Cridland, E. K., Jones, S. C., Magee, C. A., & Caputi, P. (2014). Family-focused autism spectrum disorder research: a review of the utility of family systems approaches. AUTISM, 18(3), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312472261

Croen, L. A., Zerbo, O., Qian, Y., Massolo, M. L., Rich, S., Sidney, S., & Kripke, C. (2015). The health status of adults on the autism spectrum. AUTISM, 19(7), 814–823. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315577517

Davy, G., Unwin, K. L., Barbaro, J., & Dissanayake, C. (2022). Leisure, employment, community participation and quality of life in caregivers of autistic children: A scoping review. AUTISM, 26(8), 1916–1930. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221105836

DePape, A. M., & Lindsay, S. (2015). Parents' experiences of caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder. Qualitative Health Research, 25(4), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314552455

Dunst, C. J., Jenkins, V., & Trivette, C. M. (1988). ‘Family Support Scale’. In C. J. Dunst, C. M. Trivette, & A. G. Deal (Eds.), Enabling and Empowering Families: Principles and Guidelines for Practice. MA:Brookline.

Friedrich, W., Greenberg, M. T., & Crnic, K. (1983). A short-form of the Questionnaire on Resources and Stress. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 88(1), 41–48.

Ganz, M. (2007). The Lifetime Distribution of the Incremental Societal Costs of Autism. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.4.343

Given, C. W., Given, B., Stommel, M., Collins, C., King, S., & Franklin, S. (1992). The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Research in Nursing & Health, 15(4), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770150406

Goldberg, D. P., Gater, R., Sartorius, N., Ustun, T. B., Piccinelli, M., Gureje, O., & Rutter, C. (1997, Jan). The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291796004242

Griffith, G. M., Totsika, V., Nash, S., Jones, R. S. P., & Hastings, R. P. (2012). 'We are all there silently coping.' The hidden experiences of parents of adults with Asperger syndrome* [Article]. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 37(3), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2012.701729

Grootscholten, I. A. C., van Wijngaarden, B., & Kan, C. C. (2018). High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders in Adults: Consequences for Primary Caregivers Compared to Schizophrenia and Depression. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 1920–1931.

Hare, D. J., Pratt, C., Burton, M., Bromley, J., & Emerson, E. (2004). The health and social care needs of family carers supporting adults with autistic spectrum disorders. AUTISM, 8(4), 425–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361304047225

Heller, T., Markwardt, R., Rowitz, L., & Farbe, r. B. (1994). Adaptation of Hispanic families to a family member with mental retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 99, 289–300.

Heller, T., Miller, A. B., & Hsieh, K. (1999). Impact of a consumer-directed family support program on adults with developmental disabilities and their family caregivers. Family Relations, 48, 419–427.

Herrema, R., Garland, D., Osborne, M., Freeston, M., Honey, E., & Rodgers, J. (2017a). Brief Report: What Happens When I Can No Longer Support My Autistic Relative? Worries About the Future for Family Members of Autistic Adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3659–3668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3254-6

Herrema, R., Garland, D., Osborne, M., Freeston, M., Honey, E., & Rodgers, J. (2017b). Mental Wellbeing of Family Members of Autistic Adults [Article]. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3589–3599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3269-z

Hines, M., Balandin, S., & Togher, L. (2014). The Stories of Older Parents of Adult Sons and Daughters with Autism: A Balancing Act [Article]. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12063

Hodapp, R. M., & Urbano, R. C. (2007). Adult siblings of individuals with Down syndrome versus with autism: findings from a large-scale US survey. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(Pt 12), 1018–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00994.x

Hoefman, R., van Exel, J., & Brouwer, W. B. (2013). Measuring the impact of caregiving on informal carers: a construct validation study of the CarerQol instrument. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-173

Järbrink, K., Fombonne, E., & Knapp, M. (2003). Measuring the Parental, Service and Cost Impacts of Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study [Article]. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(4), 395. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025058711465

Johnson, N. L., & Simpson, P. M. (2013). Lack of father involvement in research on children with autism spectrum disorder: maternal parenting stress and family functioning. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34(4), 220–228. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.745177

Karambelas, G. J., Filia, K., Byrne, L. K., Allott, K. A., Jayasinghe, A., & Cotton, S. M. (2022). A systematic review comparing caregiver burden and psychological functioning in caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and bipolar disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 422. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04069-w

Knapp, M., Romeo, R., & Beecham, J. (2009). Economic cost of autism in the UK. AUTISM, 13(3), 317–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361309104246

Krauss, M. W., Seltzer, M. M., & Jacobson, H. T. (2005). Adults with autism living at home or in non-family settings: positive and negative aspects of residential status. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(Pt 2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2004.00599.x

Kreutzer, J. S., Marwitz, J., & West, D. (1998). Family needs questionnaire. In Rehabilitation research and training center on severe traumatic brain injury. Medical College of Virginia.

Lawton, M., Moss, M., Fulcomer, M., & Kleban, M. (1982). A research and service-oriented multilevel assessment instrument. Journal of Gerontology, 37, 91–99.

Lee, G. K., & Shivers, C. M. (2019). Factors that affect the physical and mental health of caregivers of school-age children and transitioning young adults with autism spectrum disorder [Article]. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(3), 622–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12556

Levy, A., & Perry, A. (2011). Outcomes in adolescents and adults with autism: A review of the literature. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(4), 1271–1282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.01.023

Lewis, L. F. (2017). "We will never be normal": The Experience of Discovering a Partner Has Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(4), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12231

Liao, S.-T., & Lin, L.-Y. (2013). Mother-child relationship quality and its association with maternal well-being: A study of adolescents and adults with autism in Taiwan. Chinese Journal of Guidance and Counseling, 37, 175–206 https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2014-13425-005&site=ehost-live

Lord, C., Charman, T., Havdahl, A., Carbone, P., Anagnostou, E., Boyd, B., Carr, T., de Vries, P. J., Dissanayake, C., Divan, G., Freitag, C. M., Gotelli, M. M., Kasari, C., Knapp, M., Mundy, P., Plank, A., Scahill, L., Servili, C., Shattuck, P., … McCauley, J. B. (2022). The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. The Lancet, 399(10321), 271–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation of Australia.

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Baio, J., Washington, A., Patrick, M., DiRienzo, M., Christensen, D. L., Wiggins, L. D., Pettygrove, S., Andrews, J. G., Lopez, M., Hudson, A., Baroud, T., Schwenk, Y., White, T., Rosenberg, C. R., Lee, L. C., Harrington, R. A., Huston, M., et al. (2020). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(4). https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1

Magallon-Neri, E., Vila, D., Santiago, K., Garcia, P., & Canino, G. (2018). The Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders and Mental Health Services Utilization by Parents and Relatives Living With Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders in Puerto Rico. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 206(4), 226–230. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000760

Marsack-Topolewski, C. N. (2020). Quality of Life among Compound Caregivers and Noncompound Caregivers of Adults with Autism. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(5), 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2020.1765063

Marsack-Topolewski, C. N. (2021). Relationship between caregiver burden and basic and instrumental activities of daily living among compound and noncompound caregivers. Journal of Family Social Work, 24(4), 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2020.1861157

Marsack-Topolewski, C. N., & Church, H. L. (2019). Impact of Caregiver Burden on Quality of Life for Parents of Adult Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 124(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-124.2.145

Marsack-Topolewski, C. N., & Graves, J. M. (2019). “I worry about his future!” Challenges to future planning for adult children with ASD. Journal of Family Social Work, 23(1), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2019.1578714

Marsack-Topolewski, C. N., & Maragakis, A. (2020). Relationship Between Symptom Severity and Caregiver Burden Experienced by Parents of Adults With Autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 36, 57–65.

Marsack-Topolewski, C. N., Samuel, P. S., & Tarraf, W. (2021). Empirical evaluation of the association between daily living skills of adults with autism and parental caregiver burden. PLoS One, 16(1), e0244844. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244844

Marsack-Topolewski, C. N., & Wang, F. (2022). Dimensions of Caregiver Burden between Compound and Noncompound Caregivers of Adults with Autism. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 65(4), 402–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2021.1969609

Marsack, C., & Hopp, F. (2018). Informal Support, Health, and Burden Among Parents of Adult Children With Autism. The Gerontologist, 59. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny082

Marsack, C. N., & Perry, T. E. (2018). Aging in Place in Every Community: Social Exclusion Experiences of Parents of Adult children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Research on Aging, 40(6), 535–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027517717044

Marsack, C. N., & Samuel, P. S. (2017). Mediating Effects of Social Support on Quality of Life for Parents of Adults with Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2378–2389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3157-6

McNair, D., Lorr, M., & Droppleman, L. (1981). Profile of Mood States (POMS) Manual. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service.

Meyer, T. J., Miller, M. L., Metzger, R. L., & Borkovec, T. D. (1990). Development and validation of the penn state worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6

Mitchell PH, Powell L, Blumenthal J, Norten J, Ironson G, Pitula CR, Froelicher ES, Czajkowski S, Youngblood M, Huber M, Berkman LF. (2003). A short social support measure for patients recovering from myocardial infarction: the ENRICHD Social Support Inventory. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation, 23(6), 398–403. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008483-200311000-00001

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D. M., Ashkenazy, E., McDonald, K. E., Dern, S., Baggs, A. E., Kapp, S. K., Weiner, M., & Boisclair, W. C. (2015). "Respect the way I need to communicate with you": Healthcare experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. AUTISM, 19(7), 824–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315576221

Novak, M., & Guest, C. (1989). Application of a Multidimensional Caregiver Burden Inventory. The Gerontologist, 29(6), 798–803.

Organization, W. H (1996, WHOQOL-BREF : introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment : field trial version, December 1996. (WHOQOL-BREF). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63529

Orsmond, G. I., & Seltzer, M. M. (2007). Siblings of individuals with autism or Down syndrome: effects on adult lives. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(Pt 9), 682–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00954.x

Oti-Boadi, M., Oppong Asante, K., & Malm, E. K. (2020). The Experiences of Ageing Parents of Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) [Article]. Journal of Adult Development, 27(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-018-09325-6

Phelps, K. W., Hodgson, J. L., McCammon, S. L., & Lamson, A. L. (2009). Caring for an individual with autism disorder: a qualitative analysis. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250802690930

Pinyopornpanish, M., Pinyopornpanish, K., Soontornpun, A., Tanprawate, S., Nadsasarn, A., Wongpakaran, N., & Wongpakaran, T. (2021). Perceived stress and depressive symptoms not neuropsychiatric symptoms predict caregiver burden in Alzheimer's disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02136-7

Postorino, V., Fatta, L. M., Sanges, V., Giovagnoli, G., De Peppo, L., Vicari, S., & Mazzone, L. (2016). Intellectual disability in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Investigation of prevalence in an Italian sample of children and adolescents. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 48, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2015.10.020

Radloff, L. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Rattaz, C., Michelon, C., Roeyers, H., & Baghdadli, A. (2017). Quality of Life in Parents of Young Adults with ASD: EpiTED Cohort. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(9), 2826–2837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3197-y

Rogge, N., & Janssen, J. (2019). The Economic Costs of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Literature Review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(7), 2873–2900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04014-z

Roux, A. M., Shattuck, P. T., Rast, J. E., Rava, J. A., Anderson, K., & A. (2015). National Autism Indicators Report: Transition into Young Adulthood. Life Course Outcomes Research Program, A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, Drexel University.

Safe, A., Joosten, A., & Molineux, M. (2012). The experiences of mothers of children with autism: managing multiple roles. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 37(4), 294–302. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2012.736614

Sarriá, E., & Pozo, P. (2015). Coping Strategies and Parents’ Positive Perceptions of Raising a Child with Autism Spectrum Disorders. In Autism Spectrum Disorder - Recent Advances. https://doi.org/10.5772/58966

Schnabel, A., Youssef, G. J., Hallford, D. J., Hartley, E. J., McGillivray, J. A., Stewart, M., Forbes, D., & Austin, D. W. (2020). Psychopathology in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. AUTISM, 24(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319844636

Seltzer, M. M., & Krauss, M. W. (1989). Aging parents with adult mentally retarded children: family risk factors and sources of support. American journal of mental retardation : AJMR, 94(3), 303–312.

Smith, L. E., Hong, J., Seltzer, M. M., Greenberg, J. S., Almeida, D. M., & Bishop, S. L. (2010). Daily experiences among mothers of adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0844-y

Sonido, M. T., Hwang, Y. I., Srasuebkul, P., Trollor, J. N., & Arnold, S. R. C. (2022). Predictors of the Quality of Life of Informal Carers of Adults on the Autism Spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(7), 2997–3014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05178-3

Sonido, M. T., Hwang, Y. I., Trollor, J. N., & Arnold, S. R. C. (2019). The Mental Well-Being of Informal Carers of Adults on the Autism Spectrum: a Systematic Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00177-8

Tint, A., & Weiss, J. A. (2016). Family wellbeing of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. AUTISM, 20(3), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315580442

Tomeny, T., Barry, T., Fair, E., & Riley, R. (2017). Parentification of Adult Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder [Article]. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(4), 1056–1067. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0627-y

Tozer, R., & Atkin, K. (2015). 'Recognized, Valued and Supported'? The Experiences of Adult Siblings of People with Autism Plus Learning Disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28(4), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12145

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., et al. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

United Nations (2012). Good Practices in Family Policy Making: Family Policy Development, Monitoring and Implementation: Lessons Learnt. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/family/

van Wijngaarden, B., Schene, A. H., Koeter, M., Vazquez-Barquero, J. L., Knudsen, H. C., Lasalvia, A., & McCrone, P. (2000). Caregiving in schizophrenia: development, internal consistency and reliability of the Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire-European Version. EPSILON Study 4. European Psychiatric Services: Inputs Linked to Outcome Domains and Needs. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 39, s21–s27. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.177.39.s21

Vohra, R., Madhavan, S., & Sambamoorthi, U. (2017, Nov). Comorbidity prevalence, healthcare utilization, and expenditures of Medicaid enrolled adults with autism spectrum disorders. AUTISM, 21(8), 995–1009. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316665222

Ware, J. E., Kosinki, M., & Keller, S. D. (1995). SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. The Health Institute.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the student research assistant, Tabea Horstmann, who supported the screening process.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The research was funded by the Innovation Fund of the German Federal Joint Committee of Health Insurance Companies (Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss, G-BA, study title “BarrierefreiASS” (01VSF19011)). The funding body had no role in the design of the study or in writing the manuscript, nor did they have a role in analyses or interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(PDF 305 kb)

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dückert, S., Gewohn, P., König, H. et al. Multidimensional Burden on Family Caregivers of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Scoping Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-023-00414-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-023-00414-1