Abstract

Increasing numbers of Children and Young People on the Autism Spectrum (CYP-AS) are attending inclusive education settings in the UK, yet research about the impact on their psychosocial well-being is scarce. This qualitative review examined the experiences of CYP-AS in British inclusive education settings. Systematic data retrieval on nine electronic databases identified 22 papers reporting 19 studies that were eligible for inclusion. A combination of narrative synthesis and critical review described and synthesised studies’ findings and assessed the risk of bias. The findings reinforce the idea that integration into mainstream schools alone is insufficient to support the psychosocial well-being of CYP-AS. Social connectedness and a sense of belonging may be critical factors that improve school experiences for this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) refers to a range of neurodevelopmental conditions characterised by persistent difficulties in social interaction and communication, and restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviours, activities or interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). ASD tends to begin in childhood and persists throughout adult life, often having profound effects on functioning. Prevalence rates suggest ASD affects 1% of the child population in the United Kingdom (UK), whilst global rates are thought to be lower at 0.006% (Baird et al., 2006; Baron-Cohen et al., 2009; Elsabbagh et al., 2012). It tends to be identified before the age of five, with an average age of diagnosis at 55 months of age in the UK (Brett et al., 2016). The clinical features of ASD can impact various life domains, and difficulties appear particularly evident at school where Children and Young People on the Autism Spectrum (CYP-AS) can find it difficult to interact with peers and teachers and participate in classroom activities (Falkmer et al., 2012).

Various forms of educational provision have been set up in the UK to meet the diverse needs of CYP-AS. These include mainstream schools, specialist schools, alternative provisions (AP), specially resourced provisions (SRP) and units (Department for Education, 2015a). The choice of school is influenced by multiple factors, such as parental preference and the availability of local provision. However, mainstream schools are often the primary option for all children, offering an education alongside typically developing peers (i.e. those without developmental disabilities). They tend to be split into preschools for 0–5-year-olds, primary schools for 5–11-year-olds and secondary schools for 11–18-year-olds, though in some areas of the UK middle schools exist for children aged 9–13 years as an intermediary provision between primary and secondary levels. Specialist schools tend to enrol students from a wider age range who have Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs) or Statements of Special Educational Needs (SEN) and whose needs cannot be met at a mainstream school. EHCPs and Statements of SEN are plans put in place to support children with additional needs at school. Statements of SEN were replaced by EHCPs in England in 2014 to provide more effective support for children, for example by considering health and social care needs alongside educational needs, enhancing multi-agency involvement and extending the upper age limit for eligibility from 18 to 25 years. Often seen as provisions in-between mainstream and specialist schools are AP, SRP and units. AP tends to temporarily accommodate pupils who cannot attend mainstream schools for reasons such as exclusion or mental and physical health difficulties until a student can return to mainstream education or move to a specialist school. SRP and units provide additional specialist facilities on a mainstream school site for a smaller number of students who usually have EHC Plans or Statements of SEN. They are physically attached to mainstream schools, so CYP-AS are educated alongside typically developing peers whilst receiving more intensive support than a mainstream school usually provides. However, it is worth noting that provisions may differ on a school-by-school basis, and whilst SRP and units may be physically located on a mainstream school site, they do not guarantee that students will interact much across spaces. Whilst various definitions of “inclusive education” exist, UNESCO (2005) states that “inclusion is seen as a process of addressing and responding to the diversity of needs of all learners through increasing participation in learning, cultures and communities, and reducing exclusion within and from education” (p.13). According to this definition, inclusive education involves adapting the content and practices within mainstream schools to meet the needs of all children and places the responsibility of education for all with the regular systems that cater for the majority. This would include SRPs and units that offer specialist input alongside mainstream classes to meet the needs of CYP-AS.

CYP-AS have historically been supported in specialist schools. However, over the last three decades, increasing numbers have attended inclusive education settings. In England, an estimated 70% of CYP-AS are enrolled in mainstream schools (Department for Education, 2014). This increase is linked to the adoption of inclusive education policies advocating for a human rights-based philosophy of education for all regardless of disabilities. Although early theories, such as Wolfensberger’s (1983) theory of Social Role Valorisation, suggested that merely placing CYP-AS in inclusive education settings would be sufficient to support them at school, inclusive education philosophies recognise that mere integration into the mainstream without appropriate support in place is unlikely to be effective. Publications such as the Warnock Report (1978), the Education Act (Education Act, 1981, 2011), the Special Educational Needs and Disability Act (2001) and more recently the Children and Families Act (2014) and the Special Educational Needs and Disabilities Code of Practice (Department for Education, 2015b) have been significant developments in the UK that mandated a more inclusive model of education, where children with disabilities were included in mainstream schools with the adaptations in provision necessary to meet their needs.

The move towards inclusive education in the UK has been mirrored globally, with UNESCO’s Salamanca Statement (1994) encouraging governments around the world to adopt the principle of inclusive education for all children unless there were compelling reasons for doing otherwise. It was proposed that mainstream schools promoting the principle of inclusion were the most efficient and cost-effective method of providing education and for “combating discriminatory attitudes, creating welcoming communities, building an inclusive society, and achieving education for all” (UNESCO, 1994, p. ix). A decade later, Article 24 of the United Nations (2006) Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities advocated for the rights of children with disabilities to an education without discrimination and stipulated that reasonable adjustments and individualised support must be provided to maximise their social and academic potential, develop their sense of dignity and self-worth, and strengthen a respect for human rights and diversity. The proposed benefits of inclusive education can be seen as consistent with theories of social identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and belongingness (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), where evidence supports the notion that feeling connected to others and belonging to a group leads to improved well-being, positive self-esteem and quality of life. According to these theories, inclusive education could be linked to improved psychosocial well-being for CYP-AS due to opportunities to feel connected to others and have a sense of belonging within their school community.

There is evidence that inclusive education is linked to some benefits for CYP-AS such as improved quality of life, social development, educational performance and lower financial costs (e.g. Connor, 1998; Handleman et al., 2005; Knight et al., 2009; Parish et al., 2018; Strain, 1983). However, contradictory evidence suggests experiences of social exclusion, victimisation and bullying are common, and additional factors such as noise, crowding, limited mobility opportunities, curriculum demands and changes in routine contribute to CYP-AS’s stress and anxiety (Gray & Donnelly, 2013; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008b; Mayton, 2005; Saggers et al., 2011; Sciutto et al., 2012; Symes & Humphrey, 2010). Comorbidities of psychiatric problems, and particularly anxiety disorders, are common among CYP-AS (Joshi et al., 2010), and experiences within inclusive schools appear to contribute to their exacerbated mental health.

There is growing concern among researchers, educational staff and families about the impact of inclusive education on CYP-AS. Williams et al. (2019) explored the school experiences that contributed to CYP-AS making sense of themselves as “different” from their peers and concluded that inclusive schools seem to increase the risk of low self-esteem and mental health problems. This highlights the policy-practice gap that has been widely discussed in the literature (see Cera, 2015; Forlin et al., 2016; Grima-Farrell et al., 2011), where obstacles to implementing inclusive education policies within schools limit how successfully CYP-AS are being included. To understand the factors that contribute to CYP-AS being included effectively in mainstream schools, Roberts and Simpson (2016) explored the perspectives of students, school staff and parents and found that whilst the majority agree with the philosophical principle of inclusive education, several barriers exist to its implementation. Barriers included attitudes towards students with autism, a lack of knowledge and understanding about autism and bullying and a lack of necessary support at an individual, class and school level. Both reviews highlight a dearth of research into the experiences of CYP-AS and call for further investigation.

Despite the difficulties with implementing inclusive education policies, CYP-AS continue to get enrolled within inclusive settings in the UK and an understanding of how this affects their psychosocial well-being is an important avenue for research. Several new studies have been published since the reviews of Williams et al. (2019) and Roberts and Simpson (2016) which further elucidate the lived experiences of CYP-AS in inclusive schools and many have been conducted in the UK. Considering that global educational systems vary considerably, a review focused on British schools was thought to assist educational providers and policymakers in making improvements to the school experiences for CYP-AS. The reviews of Williams et al. (2019) and Roberts and Simpson (2016) both had an international focus, which makes it difficult to apply their findings specifically to the UK. The current review aims to provide an up-to-date understanding of the lived experiences of CYP-AS in inclusive education settings in the UK from the perspectives of the young people themselves, their teachers and parents. It attempts to answer the following research question: how does inclusive education in the UK affect the psychosocial well-being of CYP-AS? In doing so, this review hopes to identify factors that can be targeted to improve the inclusive school experience for this population.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

This systematic review followed PRISMA reporting guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). A review protocol was registered in advance on PROSPERO, registration number CRD42020158737. The research was conducted in the UK in part fulfilment of the first author’s doctoral degree in clinical psychology. The authors searched the Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, the British Education Index, CINAHL, EducatiOn-Line, ERIC, Proquest Dissertations and Theses Online, PsycInfo, Scopus and Web of Science. Searches took place on 19 April 2021, with no restriction on publication date or language, using a Boolean search strategy and MeSH terms to combine keywords relating to ASD and inclusive/mainstream education (see Table 1). The reference lists of included studies, and relevant reviews were hand-searched for additional papers. Studies were included if they:

-

1.

Focused on understanding the inclusive school experiences of CYP-AS aged 0–18 who were either currently enrolled in inclusive education settings or had previously spent time in such settings

-

2.

Explored the views of CYP-AS, their parents and/or school staff

-

3.

Used qualitative methods

-

4.

Were conducted in the UK

-

5.

Were published in peer-reviewed journals

The importance of gathering multiple perspectives when exploring the experiences of CYP-AS has been highlighted in previous research (e.g. Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a); therefore, a multi-informant approach was chosen to gather the perspective of all those with an input into the educational experiences of this population. The age range was chosen to reflect the typical ages of school-aged children in the UK (5–18 years old), whilst also acknowledging that ASD diagnoses are often given earlier. Qualitative research has the advantage of gaining rich descriptions about the lived experiences of populations; therefore, it was deemed appropriate to limit the current review to this form of research design. The limit to studies published in peer-reviewed journals was applied with the intention of identifying high-quality, credible research.

Studies were included if they employed creative qualitative approaches, such as drawing tasks and visual prompts for indicating thoughts and emotions, as well as traditional interview or focus group formats in an attempt to capture the experiences of a more diverse population of CYP-AS. Exercises based on pictorial representations can be a more helpful way of communicating with CYP-AS and those who have verbal or written communication problems (Kirkbride, 1999). The authors also included studies that were conducted in a range of settings, providing that the participants had spent time being educated in inclusive education settings and the research was specifically focused on understanding their experiences of inclusive education. Even if CYP-AS were currently enrolled in a different type of provision, it was deemed valuable to still gather their views if they had previous experience of inclusive settings. If a study produced duplicate data across multiple research papers, only the paper with the fullest dataset was included. However, if different findings were reported across papers, then they were all included. Studies were excluded if they focused on understanding how students experienced the transition between schools (as this was felt to relate more specifically to the transition, rather than the school experience itself), if they were evaluating a specific intervention, such as social skills training, or if they simply reported a summary of open-ended survey responses with no development of themes.

Data Analysis

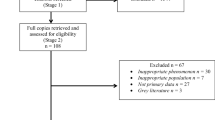

All duplicates were removed from the initial searches, and the titles and abstracts of papers were screened against the eligibility criteria. Full-text articles of potentially eligible studies were retrieved, and authors contacted if articles were not found. Two reviewers (SE, ZK) independently assessed all full-text articles for eligibility, documenting reasons for exclusion. Inter-rater reliability was high at 95%. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus, and a third reviewer (RV) was consulted if an agreement was not reached. This led to one paper being removed from the analysis due to the focus on the experience of teaching assistants. Reviewers were not blind to the journals or authors of the studies reviewed.

A data extraction spreadsheet was used to record study characteristics (see Table 2), reported themes and data extracts from eligible studies and included the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme’s (CASP; 2018) quality tool for assessing the risk of bias in qualitative research. The CASP tool contains ten questions to systematically assess whether studies have been designed and carried out robustly and ethically, whether the results are valid and have been reported clearly, and whether the study makes a valuable contribution to the literature. High-quality studies were those that met over seven of the CASP criteria, moderate-quality studies met four to six criteria, and low-quality studies met up to three criteria. The first author extracted the data from the included studies and two reviewers (SE, ZK) blindly and independently assessed the quality of the studies. Inter-rater reliability of the quality assessment was high at 90%. No study was excluded on the basis of quality appraisal; it was conducted as a way of highlighting potential limitations within papers and the sample overall. Inter-rater reliability was not completed at the data extraction stage due to time pressures, which is a common practice adopted by other reviews (e.g. Kelly et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2019).

Given that the included studies were qualitative and highly heterogeneous, a meta-synthesis was not possible. A combination of narrative synthesis and critical review was conducted instead, which involved describing the characteristics of included studies and synthesising their findings. The first stage involved reading and re-reading the articles, noting down the main themes identified by the authors of each study and recording data extracts (direct quotes from participants) in a database. The second stage involved looking at the themes across studies and generating preliminary overarching themes, which were revised through an iterative process of re-reading the articles and considering how well they captured the themes from the articles. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems framework was used as a guide to structuring the themes by focusing on the student first, then widened to include their peers and teachers, and then to the whole school community and ethos. Finally, themes which frequented the majority of studies were identified as key themes.

Results

The review process resulted in the inclusion of 22 papers published between 2000 and 2021, relating to 19 studies (see Fig. 1 for the PRISMA study selection flowchart; Moher et al., 2009). Two papers (Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a, 2008b) were drawn from one larger research programme and therefore contained the same participants. However, the publications reported on different aspects of the study deemed relevant to this review, and so they were both included. This was also the case for three other papers linked to one study (Goodall, 2018, 2019; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019). To avoid duplication of data, the description of participants and school settings below only includes data from the 19 studies. One study (5.3%) reporting data across three papers took place in Northern Ireland (Goodall, 2018, 2019; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019) and the remaining studies took place in England. Thirteen papers were published since the reviews of Roberts and Simpson (2016) and Williams et al. (2019) conducted their literature searches.

At least 499 participants (N = 142 CYP-AS (28.5%), N = 256 parents/carers (51.3%), N = 101 educational staff (20.2%)) were included in the review (one study did not report the sample size of parents and school staff; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008b). Of the 142 CYP-AS, 23 (16.2%) were of primary school age, two (1.4%) were of middle school age and the remaining 117 (82.4%) were at the secondary school level. Only 37 were female (26.1%), although four papers did not report the gender of participants (Holt et al., 2012; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a, 2008b; Tobias, 2009). Very few details were given about the demographics of CYP-AS participating in the studies. Only three studies reported participants’ ethnicities, which corresponded to 23 CYP-AS (16.2%) of the sample (Calder et al., 2013; Cook et al., 2016, 2018); 16 were “White British” (11.3%), two were “White Other” (1.4%), one was “Mixed Race” (0.7%) and four were “Black African” (2.8%). One study reported that the research took place in an ethnically diverse community but gave no details about its’ participants ethnicities (Hebron & Bond, 2017). Five studies (22.7%) reported on intellectual capabilities (Calder et al., 2013; Emam & Farrell, 2009; Holt et al., 2012; Moyse & Porter, 2015; O’Hagan & Hebron, 2017); all of these CYP-AS had average or above average intellectual abilities or were labelled as “high-functioning”. One paper described a school involved in the study as catering for students with severe learning difficulties, though gave no details about participants’ intellectual functioning (Humphrey & Lewis, 2008b). Learning difficulties, such as dyslexia, dyspraxia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, are different from intellectual disabilities as they are specific problems with processing certain forms of information that do not affect general intellect (Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities, 2023). See Table 2 for the study characteristics of the included studies.

Three studies (15.8%) were conducted solely at the primary school level (Calder et al., 2013; Moyse & Porter, 2015; Warren et al., 2020), and 11 studies reporting data across 14 papers (57.9%) were conducted solely at the secondary school level (Connor, 2000; Cook et al., 2016, 2018; Dillon et al., 2016; Goodall, 2018, 2019; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019; Holt et al., 2012; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a, 2008b; Landor & Perepa, 2017; O’Hagan & Hebron, 2017; Tobias, 2009; Tomlinson et al., 2021). Two studies (10.5%) were conducted across both primary and secondary schools (Emam & Farrell, 2009; Hebron & Bond, 2017), one study (5.3%) was conducted across both middle and secondary schools (Myles et al., 2019) and the school level was not reported for two studies (10.5%; Waddington & Reed, 2006; Whitaker, 2007). In terms of school type, one study reporting data across three papers (Goodall, 2018, 2019; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019) was conducted in an AP and voluntary study hub for home-schooled children, and seven studies were conducted in a unit or SRP (Hebron & Bond, 2017; Holt et al., 2012; Landor & Perepa, 2017; Myles et al., 2019; O’Hagan & Hebron, 2017; Tobias, 2009; Warren et al., 2020). Although the focus of this review is on inclusive education settings, the students who attended an AP and study hub had all spent time in mainstream schools, and they were being asked about their experiences in mainstream education as part of the research, so the studies were included as they provided information deemed relevant to the review. For the eight studies where CYP-AS attended AP, SRP, units and a study hub, the level of detail about the amount of time spent in mainstream education varied; four studies reporting across six papers did not report this information at all (Goodall, 2018, 2019; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019; Hebron & Bond, 2017; Landor & Perepa, 2017; Myles et al., 2019), two studies reported that CYP-AS attended all mainstream lessons except one or two (Holt et al., 2012; Warren et al., 2020), one study reported that CYP-AS attended all mainstream lessons (Tobias, 2009) and another study reported that CYP-AS attended predominantly all mainstream classes (O’Hagan & Hebron, 2017).

Quality Appraisal

Fourteen papers were deemed high quality, seven moderate quality and one low quality (see Table 2). The authors of high-quality studies clearly reported research aims and findings, adopted appropriate methodology and recruitment strategies, collected and analysed data rigorously and ethically and outlined the value of the research to the wider literature. Only one study reporting data across three papers commented on the relationship between researchers and participants (Goodall, 2018, 2019; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019), which is concerning considering the subjective nature of qualitative research. Papers of moderate quality insufficiently reported recruitment strategies and data analysis, which introduces potential threats to the reliability and validity of results. The paper regarded as low quality (Connor, 2000) did not report on research design, recruitment strategy, data collection, analysis or ethical issues, which made it difficult to assess the accuracy and reliability of its results. Six studies did not report whether they sought ethical approval from a research committee and/or whether informed consent was gained from participants (Connor, 2000; Dillon et al., 2016; Emam & Farrell, 2009; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008b; Waddington & Reed, 2006; Whitaker, 2007); therefore, it is unclear whether these practices took place. If not, this raises concern considering the research was conducted with individuals where issues surrounding capacity, communication and consent are frequent.

Key Themes

Six key themes were identified and discussed with the third reviewer: awareness and understanding of ASD, identity and belonging, interactions with peers, interactions with educational staff, school environment and school culture. Similar themes arose among CYP-AS, their parents and educational staff; therefore, data is presented together for the stakeholders. Whilst the two themes of identity and belonging and interactions with peers pertain to related experiences within inclusive settings, the data seemed to capture a difference in the quality of peer relationships and how this contributed to the students’ sense of who they were (i.e. their identity) and how much they felt they belonged among peers and within their school. The identity and belonging theme therefore relates more to the students’ sense of who they are, and their feelings of being valued, accepted and respected by peers and the wider school community, whereas the theme of interactions with peers relates instead to the quality of their social interactions, such as experiences of friendships and bullying.

Awareness and Understanding of ASD

Discussions around awareness and understanding of ASD frequented eight high-quality papers and five moderate-quality papers (Cook et al., 2016; Dillon et al., 2016; Goodall, 2018, 2019; Hebron & Bond, 2017; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a, 2008b; Landor & Perepa, 2017; Myles et al., 2019; Tobias, 2009; Tomlinson et al., 2021; Warren et al., 2020; Whitaker, 2007). There were several reports of peers having little understanding of ASD and the negative impact this had on interactions and CYP-AS being viewed differently (Goodall, 2018; Landor & Perepa, 2017; Tomlinson et al., 2021; Warren et al., 2020). However, when peers had some understanding of ASD, there were accounts of them targeting the characteristics such as sensory sensitivities to cause upset: “it would be things like, things stuck on his back, it’ll be tapping, it’ll be looks, it would be scraping” (Cook et al., 2016, p.259). A lack of awareness and understanding of ASD among teachers was also reported as challenging. Many CYP-AS felt teachers did not understand their needs and in some cases were not motivated to support them: “[bad teachers] don’t use training they have to help” (Goodall, 2019, p.24). This raised concerns about CYP-AS’s needs not being met effectively as a result (Myles et al., 2019; Tobias, 2009).

Parents in Hebron and Bond’s (2017) study felt it was vital for all staff to be autism-aware as their children had experienced prolonged episodes of bullying and exclusion as a result of educational staff not effectively managing difficulties: “I would be like drop him off at nine … by the time I reach work I had to go and pick him up” (p.563). This suggests ASD training could be a useful approach for increasing understanding. However, as a young person in Goodall’s (2019) study suggested, ASD training is not a straightforward solution as “training can make [teachers] bad as they use it to treat kids as thick” (p.24). This raises a question about how understanding can be facilitated sensitively and effectively. In Whitaker’s (2007) study, which rigorously analysed data and had a considerably larger sample size than other studies in this review, parents described the importance of teachers understanding the condition whilst also understanding the individual and the challenges they face. One mother powerfully expressed “I would like the staff to understand who my daughter is and what it feels like to be her” (Whitaker, 2007, p.175).

Although most of the studies that contributed to this theme discussed understanding and awareness of ASD in relation to peers and educational staff, two studies of high and moderate quality discussed CYP-AS engaging in a process of self-understanding (Dillon et al., 2016; Tobias, 2009). CYP-AS in Dillon et al.’s (2016) study showed a level of self-awareness that challenges descriptions in the literature of individuals on the autism spectrum lacking this ability (Ferrari & Matthews, 1983): “I’m getting more angrier now than I was in year 6. And even from now it could start to get more worse. I’m quite concerned” (p.225). Researchers tend to agree that individuals with ASD do exhibit difficulties with self-awareness, though not lacking the ability altogether (Huang et al., 2017). The benefits associated with developing this skill include protection against autistic burnout, recognition of passions and interests, cultivation of relationships with others and the development of strategies to cope with their environment (Mantzalas et al., 2022; South & Sunderland, 2022). It is likely that such self-awareness also occurs in other educational settings and points towards the benefit of schools supporting CYP-AS to develop greater self-understanding.

Identity and Belonging

Issues relating to how CYP-AS saw themselves and felt part of their school community were described by CYP-AS, their parents and educational staff across 16 papers (Calder et al., 2013; Connor, 2000; Cook et al., 2018; Goodall, 2018; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019; Hebron & Bond, 2017; Holt et al., 2012; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008b; Moyse & Porter, 2015; Myles et al., 2019; O’Hagan & Hebron, 2017; Tobias, 2009; Tomlinson et al., 2021; Waddington & Reed, 2006; Warren et al., 2020; Whitaker, 2007). CYP-AS spoke frequently about wanting to fit in with their peers and how social inclusion underpinned feelings of belonging at school: “it’s like wanting to be there and feeling that people want you to be there” (Myles et al., 2019, p.11). Feeling valued and accepted resulted from experiences where CYP-AS were heard and listened to within classrooms and actively included in activities. Unfortunately, the studies in this review revealed an overall picture suggesting experiences of loneliness, social exclusion and feeling different were common.

Limited social and communication skills regularly presented barriers for CYP-AS connecting with their peers: “he probably tries too hard, which is why he annoys people so much because he doesn’t understand the rules, and he makes the wrong comments” (O’Hagan & Hebron, 2017, p.16). This appeared to accentuate feelings of being different in a negative way: “I don’t like having autism. I think it makes me different to other people and I think other people treat me as being different … I was often called a geek or weirdo” (Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019, p.508). CYP-AS in Humphrey and Lewis’s (2008a) study chose words such as “retard” and “freak” to describe how they saw themselves (p. 31). Such value-laden terms illustrate the powerful descriptions that some CYP-AS incorporate into their self-concepts. In contrast, some CYP-AS thought more positively about feeling different, though this was more likely in individuals who had strong friendships and were doing well academically (Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a). Warren et al. (2020) reported evidence of an identity clash for CYP-AS who attended an SRP attached to a mainstream school, with one staff member describing a student feeling like “a big fish in the base but a very small fish in mainstream” (p.10–11), although the CYP-AS in the study did not report any difficulties with being different due to attending both settings, describing it instead as “cool” and “exciting” (p.10).

Humphrey and Lewis (2008a) hypothesised that the negative view of being different had likely arisen through feedback from other people, leading CYP-AS to feel forced to adapt their behaviour to fit in. This seemed particularly common in females, consistent with research suggesting masking behaviour is associated more with the female expression of ASD (Baldwin & Costley, 2016; Cridland et al., 2014; Kenyon, 2014; Rynkiewicz et al., 2016). A girl in Cook et al.’s (2018) study explained “I thought if I changed to be like my other friend, they’ll listen to me, and they all did, so I was like, I’ll keep it that way” (p.310). Whilst masking seems to enable CYP-AS to hide their differences to be accepted and feel a sense of belonging, parents were often concerned that it led to symptoms being missed and more significant problems subsequently developing (Cook et al., 2018; Whitaker, 2007). Interestingly, parents and a school psychotherapist in Tomlinson et al.’s (2021) study reported that receiving an ASD diagnosis had positively reduced masking tendencies and improved the young person’s self-awareness. However, this study insufficiently described their recruitment strategy and data analysis process; therefore, the reliability of this finding is unclear.

Interactions with Peers

Mainstream school is an intensely social environment, and ASD characteristics often present unique challenges to peer relationships. Many CYP-AS, their parents and educational staff highlighted commonplace experiences of rejection, isolation and bullying: “I was isolated and separate, in like a bubble of depression and anxiety... but, I still felt the centre of attention with others looking at me and judging” (Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019, p.507). ASD characteristics such as social naivety appeared to make CYP-AS particularly vulnerable to bullying (Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a). It is not clear whether bullying was always because a young person had ASD. However, the victimisation through targeting of specific sensory sensitivities described earlier suggests bullying and stigma related to the experience of ASD certainly do occur.

Negative peer interactions linked to ASD characteristics pose an interesting dilemma related to the disclosure of diagnoses in the school setting. It appeared to be a contentious issue among CYP-AS, with some preferring to disclose in order to elicit support and understanding from others, whilst others preferred to keep it private for fear of attracting the stigma that diagnostic labels often create. For some CYP-AS, any level of disclosure was perceived as a barrier to being considered “normal”: “I’d rather they not know because then I wouldn’t be treated differently” (Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a, p.40). However, there were also examples of sensitively handled disclosures to peers facilitating positive peer relationships: “the more they learn about Asperger’s the more sympathetic they feel” (Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a, p.40). In these circumstances, Humphrey and Lewis (2008a) suggested that CYP-AS feel more capable of navigating the complex world within an inclusive school, due to the support from peers contributing to a positive sense of self.

Experiences of friendships for CYP-AS were reported across ten studies, with high consistency across the accounts of CYP-AS, parents and educational staff (Calder et al., 2013; Cook et al., 2016, 2018; Hebron & Bond, 2017; Holt et al., 2012; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a; Myles et al., 2019; Tomlinson et al., 2021; Warren et al., 2020; Whitaker, 2007). CYP-AS in Myles et al.’s (2019) study—which was one of five high-quality studies with a female-only sample—described friendships as an important factor for overall happiness at school by providing a sense of social security that helped CYP-AS to cope with the school environment. However, friendships were often described as confusing, unreciprocated and impacted significantly by limited social and communication abilities. It was common for CYP-AS to befriend peers with ASD or other differences (Cook et al., 2016, 2018; Tomlinson et al., 2021), which is consistent with ideas proposed by social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) suggesting individuals seek out relationships with similar others to bolster their personal identity. In contrast, some CYP-AS preferred being alone (Calder et al., 2013), suggesting individual differences in motivation to develop friendships. Studies conducted in SRPs or units indicated that these educational provisions seem to facilitate friendships in a way that felt safe and contained and where help is available to support the navigation of complex social interactions (Hebron & Bond, 2017; Holt et al., 2012; Warren et al., 2020).

Interactions with Staff

The importance of relationships with educational staff for CYP-AS in inclusive schools was discussed frequently. In Dillon et al.’s (2016) study, these were mostly seen positively and were linked to staff being seen as caring and helpful. Relationships were viewed negatively when there was little interaction between CYP-AS and their teachers and when teachers did not adapt lessons to meet the needs of CYP-AS. In Emam and Farrell’s (2009) study, ASD characteristics seemed to create tension and frustration for teachers, where they found the task of modifying their language difficult to accommodate the literality of thought often exhibited by CYP-AS: “She used to take things very literally … if I say to somebody… ‘pull your socks up’… she would not understand” (p.414). Teachers in this study described how difficulties with social and emotional understanding affected their teaching methods and their relationship with CYP-AS. Teachers were less able to rely on facial expressions to evaluate the pace of their teaching and check pupil’s understanding, or to convey nonverbal messages, and some teachers were noted to resent the extra effort they had to make to accommodate CYP-AS in their class: “he really does not show sort of the excitement that some of the other children might do” (p.413, Emam & Farrell, 2009). Many teachers reported feeling conflicted about whether their responsibilities lay with CYP-AS or with other students, and many found it hard to tailor their practice to meet the diverse needs of the classroom (Emam & Farrell, 2009; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a, 2008b). This was mirrored in the perspective of a young person in Tomlinson et al.’s (2021) study: “people higher in the school think… well I don’t need to do it now because we’ve got curriculum support staff… leave it to that lot” (p.11).

The inclusion of CYP-AS was seen more favourably by mainstream teachers when additional support was offered by support staff. However, several accounts highlighted that the presence of support staff reduced interaction between CYP-AS and their teachers, and increased the likelihood of bullying due to their physical presence signalling that CYP-AS were different from their peers (Emam & Farrell, 2009; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a, 2008b; Landor & Perepa, 2017; Tomlinson et al., 2021). Schools where support staff helped the whole class rather than just CYP-AS or where support was provided by a combination of staff and peers, somewhat overcame these problems (Emam & Farrell, 2009; Landor & Perepa, 2017). However, these papers did not describe how they selected participants so sample biases are possible.

School Environment

Sensory aspects of the school environment were commonly reported as contributing to the distress of CYP-AS in inclusive schools, and particularly at secondary level where schools were larger and busier. A young person in Tomlinson et al.’s (2021) study shared that “the fire alarm is horrific… usually I get so annoyed I’d bite my fingers” (p.9). Peers were often reported to provide unwelcomed distraction in the classroom, which hindered CYP-AS from completing academic tasks and getting necessary support from teachers: “classmates talk a lot … they just keep talking and talking” (p.226, Dillon et al., 2016). Humphrey and Lewis (2008b) noted that CYP-AS in their study were often put into the lowest academic sets, which tended to be noisier and more disruptive: “In English [lessons] there was so much noise. I just wanted the class to be quiet and I can get on with my work” (p.138). The teachers that took part in the study commented on how this impacted how much support they could provide: “I spend so much time disciplining … I have to admit, out of the pupils I teach with autism, he is the one I speak to the least because of the class that he is in” (p.138).

The order and predictability that many CYP-AS rely on appeared to be challenged by the school environment, where sudden room or timetable changes were common (Humphrey & Lewis, 2008b). This is consistent with reports from CYP-AS, parents and educational staff that unstructured times during the school day, such as break and lunch times, were particularly difficult: “the in between times, when we go to assembly, play, the snack, that’s the time they struggle with the most” (Warren et al., 2020, p.7). Many CYP-AS searched for quiet, safe spaces to reduce their anxiety (Calder et al., 2013; Connor, 2000; Hebron & Bond, 2017; Moyse & Porter, 2015; Whitaker, 2007), and SRPs and units often provided an escape from the overwhelming nature of mainstream school (Holt et al., 2012; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008b; Landor & Perepa, 2017; Warren et al., 2020).

Whilst the environmental challenges described so far were consistently reported by CYP-AS, their parents and educational staff, some differences were apparent. Descriptions offered by CYP-AS focused largely on current distress, whereas parents and educational staff reflected more on the longer-term benefits of exposure to the mainstream environment for later life, which included building resilience and coping strategies, having access to the full curriculum, and opportunities for social skill development (Hebron & Bond, 2017; Landor & Perepa, 2017; Tobias, 2009; Waddington & Reed, 2006; Warren et al., 2020). A parent in Waddington and Reed’s (2006) study explained that CYP-AS “are being forced into social situations that they are going to encounter for the rest of their lives” (p. 159). If coping with the stress of mainstream schools is beneficial in the long term, schools must be well-equipped to support CYP-AS to tolerate distress in the short term.

School Culture

Eight studies commented on the impact of the wider school culture on CYP-AS (Calder et al., 2013; Cook et al., 2016; Hebron & Bond, 2017; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008b; Tobias, 2009; Tomlinson et al., 2021; Waddington & Reed, 2006; Whitaker, 2007). The importance of an inclusive and welcoming school ethos, high-quality communication between staff and parents, and commitment and willingness of all educational staff to include CYP-AS in inclusive schools were seen as factors that facilitated CYP-AS to be better supported. In Hebron and Bond’s (2017) study, parents provided examples of inclusive practices, such as improving autism awareness across the whole school and including CYP-AS in learning tasks with peers, that helped students to feel more included: “It just seems everybody around the school seems a lot more aware, teachers … the dinner lady. They all seem to know a little bit more” (p.465), “He wasn’t included in the mainstream homework last time, now he’s doing the same as what the other kids are doing so he doesn’t feel left out” (p.465). The positive effects of these practices can be understood from a social identity and belongingness perspective, where the structures put in place facilitate a sense of acceptance, connectedness and collective identity. Tomlinson et al. (2021) concluded that “adoption of a whole school approach to supporting autistic pupils is a key contributing factor to successful placement [in mainstream schools]” (p.5).

For parents in particular, good communication between home and school was “worth gold” (Whitaker, 2007, p.176), especially when educational staff listened to and acted upon parental knowledge and expertise. In Tobias’s (2009) study, parents spoke about the willingness of staff to listen to parents regardless of whether their concerns appeared trivial: “You just feel no matter how small the incident, or how silly it might seem, to you and your child it isn’t. … Every time I’ve brought an issue to the school … I have never felt stupid” (p.156). Educational staff felt that when leadership teams committed to promoting an inclusive school environment and established effective communication channels with the wider staff team, this helped to better meet the needs of CYP-AS. This was commented on by an ASD resource manager in Humphrey and Lewis’s (2008b) study: “My perception is that the senior management are on board with it … they’re sort of receptive to the ideas that you know that they can open up the school and make it more accessible, you know, to these children who have individual needs” (p.134). Humphrey and Lewis (2008b) concluded that the “bottom line” is that “whilst some students with ASD felt part of their school community … others were unable to actively participate, leading to a state of ‘integrated segregation’ that was often a direct consequence of the practice of teachers and/or LSAs (learning support assistants)” (p.135). Similar considerations were rarely offered by CYP-AS themselves, which may simply reflect the fact that these practices sometimes occur outside of the young person’s awareness, though nevertheless highlight the importance of gathering multiple perspectives to shine light on different aspects of experience.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to synthesise the qualitative evidence of the lived experience of CYP-AS in inclusive schools in the UK. Six themes highlighted how issues related to understanding and awareness of ASD, identity and belonging, interactions with peers and educational staff, and the school environment and culture were important aspects of the school experience for CYP-AS. Four themes were identified in previous reviews (Roberts & Simpson, 2016; Williams et al., 2019), indicating consistency of experiences over time and cross-culturally. However, the current review adds an identity/belonging aspect and takes a wider view of how school culture can facilitate positive experiences. There was considerable consistency among the reports of CYP-AS, their parents and educational staff, suggesting a good level of shared understanding among stakeholders with an input in the educational experiences of CYP-AS. Stark differences in the experiences of CYP-AS were rare and those that did appear seemed to be examples of understandable individual differences. Most studies focused on CYP-AS of secondary school age, but from the small number that focused on primary schools, there did not seem to be any obvious differences between the students’ experiences, and the three papers that included students across primary/middle and secondary schools did not describe any differences across levels. Indeed, there are developmental differences between primary and secondary school aged children, so differences would be expected as CYP-AS progress through school years and face increasing academic demands and more complex social relationships. Differences in the developmental trajectories of females and males would also be expected, considering that studies have indicated sex differences from early infancy throughout adulthood. Females with autism tend to engage in fewer and less intense restrictive interests and repetitive behaviours and have less impaired social communication and social competence compared to males with autism (McFayden et al., 2023). This may mean females could be more likely to go undiagnosed with their needs not being recognised, which would limit the support offered to them at school. Comparing the experiences of CYP-AS of different sexes across school levels would be a useful avenue for further research so that specific needs can be met more effectively.

This review illustrates that mainstream school can be a confusing and difficult system for CYP-AS to navigate. ASD characteristics, and how they were responded to by others, often contributed to CYP-AS experiencing difficulties that affected their academic learning and psychosocial well-being. Many CYP-AS felt different, devalued and isolated, which was exacerbated by negative interactions with peers, staff and the school environment. This suggests the theory of SRV (Wolfensberger, 1983) is insufficient in explaining how inclusive education can facilitate positive experiences at school for this population; unsurprisingly, simply attending a mainstream school does not automatically mean CYP-AS will flourish. Incorporating ideas from theories of social identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and belongingness (Baumeister & Leary, 1995) may offer a more comprehensive understanding; feeling a sense of belonging and connectedness to a social group that society deems as socially valuable may help to better support CYP-AS in inclusive settings. When acceptance and supportive relationships are facilitated by an in-depth, empathetic understanding of the lived experiences of CYP-AS, negative experiences are likely to be counteracted and desired experiences such as reciprocal friendships and positive self-esteem made more accessible. Positive accounts across a few studies suggest this may be the case, as CYP-AS had more positive experiences at school when they had supportive friendships and felt a sense of belonging to their peer group and school as a whole, in addition to where a culture of acceptance was established through the school ethos and commitment to inclusive practices by staff.

A number of limitations are present in the studies included in this review, challenging the validity of their findings. Whilst the majority of studies were deemed to be of high quality afforded by appropriate reporting of the aims, methodology, data collection, analysis and contributions to the wider literature (Calder et al., 2013; Cook et al., 2016, 2018; Dillon et al., 2016; Goodall, 2018, 2019; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019; Hebron & Bond, 2017; Moyse & Porter, 2015; Myles et al., 2019; O’Hagan & Hebron, 2017; Waddington & Reed, 2006; Warren et al., 2020; Whitaker, 2007), several studies were marked as moderate or low quality due to insufficient details being reported (Connor, 2000; Emam & Farrell, 2009; Holt et al., 2012; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008a, 2008b; Landor & Perepa, 2017; Tobias, 2009; Tomlinson et al., 2021). Most studies did not report the intellectual capabilities of their participants, and of those that did, the CYP-AS tended to have average or above average intellectual capabilities or were labelled as “high-functioning”. It is therefore unclear whether the experiences of CYP-AS identified in this review would be similar to CYP-AS with intellectual disabilities. Individuals with ASD and an intellectual disability are understudied compared to those with ASD without an intellectual disability (Siegel, 2018). Similarities in their school experiences are likely; however, research shows that social, adaptive and communication skills tend to be more severe when multiple conditions are present (Matson et al., 2009); therefore, CYP-AS with an intellectual disability are likely to face additional challenges at school that would require specific support to meet their needs. Ethnicity data was also rarely reported and few females were included in the studies, which is consistent with the historical underrepresentation of females in autism research. The male bias was 3:1 in this review, which is similar to ratios found elsewhere (Baird et al., 2006; Kasari et al., 2016). Further research would benefit from engaging a more diverse group of CYP-AS in research, both in terms of gender, ethnic backgrounds and intellectual abilities, and ensuring these details are reported. Considering the diverse range of needs along the autism spectrum, and the varying challenges of developing a sense of identity and belonging for individuals from diverse backgrounds, this would be an important area for further work.

Acknowledging that qualitative research is a subjective process, the first author of this review reflected on the bias that her position and individual perspective may have introduced. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems framework came to mind during data synthesis, which likely influenced how key themes were structured; a different guiding framework may have resulted in alternative key themes arising. Personal interests in social identity are likely to have filtered the lens used to digest information, meaning that other perspectives were possibly ignored. Similar biases may have been active during the development of themes, where links to identity, belonging and social interactions dominate. These potential biases would have been somewhat mitigated through conversations with the other two authors throughout this review, though no inter-rater reliability checks were conducted on the data extracted and theme development due to time constraints; therefore, this presents a threat to the objectivity of the information presented. This review nevertheless offers a novel perspective of the under-explored experiences of CYP-AS and draws on the perspectives of multiple informants to provide a holistic view that can be used to identify areas in need of improvement. This is the only review to focus specifically on the UK, meaning that its findings can serve to inform British educational policy and provision.

Notwithstanding the limitations of this review and the studies involved, a novel and useful synthesis of the literature is offered pertaining to the real-world experiences of CYP-AS attending inclusive schools in the UK. Education providers and policymakers are encouraged to draw on the findings when considering improvements to the school experiences for CYP-AS and those with similar difficulties. Practical recommendations could include co-designing ASD training programmes with CYP-AS to encourage a more empathetic understanding of challenges faced at school, quiet spaces to encourage the development of adaptive coping skills that help CYP-AS to build up tolerance to the distressing aspects of the inclusive environment, therapeutic opportunities to support CYP-AS to develop self-understanding and awareness, social clubs for CYP-AS and their peers based on shared interests and hobbies to encourage social connectedness, and adoption of inclusive practices by senior management teams that permeate throughout staff levels to create a culture of acceptance and belonging, for example, by having an explicitly inclusive school ethos, publicising the school’s inclusion policy and creating effective communication channels among staff and with parents. Some of these recommendations are consistent with existing research investigating the effectiveness of interventions to improve the experiences of CYP-AS in inclusive education settings. Substantial work has focused on improving peer relationships, such as by offering social lunch clubs based on the interests of CYP-AS to increase social interactions (Koegel et al., 2012, 2013). Carter et al. (2010) provide a comprehensive review of the intervention literature promoting social interaction. Work has also been undertaken to increase self-determination skills that promote goal setting and attainment, self-awareness, problem-solving and decision-making and has demonstrated that CYP-AS can benefit from these interventions to navigate the school experience more effectively (see Morán et al., 2021 for a recent review). There is also emerging evidence for the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving peer and teacher awareness of autism within schools (see Cremin et al., 2021 for a recent review) and building a sense of community at a whole school level (Carrington et al., 2021; Shochet et al., 2021). Schools will undoubtedly rely on support from local governments to implement such recommendations. However, these practices could significantly enhance the experiences of CYP-AS by reducing negative feelings of being different, whilst encouraging the formation of strong connections with others and a sense of belonging within an environment that promotes acceptance and values diversity.

Data Availability

Data associated with the eligibility and quality assessments are provided as supplementary files. No other data is available.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., Meldrum, D., & Charman, T. (2006). Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: The Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Lancet, 368(9531), 210–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7

Baldwin, S., & Costley, D. (2016). The experiences and needs of female adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(4), 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315590805

Baron-Cohen, S., Scott, F. J., Allison, C., Williams, J., Bolton, P., Matthews, F. E., & Brayne, C. (2009). Prevalence of autism-spectrum conditions: UK school-based population study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(6), 500–509. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059345

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

Brett, D., Warnell, F., McConachie, H., & Parr, J. R. (2016). Factors affecting age at ASD diagnosis in UK: No evidence that diagnosis age has decreased between 2004 and 2014. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(6), 1974–1984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2716-6

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Calder, L., Hill, V., & Pellicano, E. (2013). “Sometimes I want to play by myself”: Understanding what friendship means to children with Autism in mainstream primary schools. Autism, 17(3), 296–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312467866

Carrington, S. B., Saggers, B. R., Shochet, I. M., Orr, J. A., Wurfl, A. M., Vanelli, J., & Nickerson, J. (2021). Researching a whole school approach to school connectedness. International Journal of Inclusive Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1878298

Carter, E. W., Sisco, L. G., & Chung, Y.-C. (2010). Peer interactions of students with intellectual disabilities and/or autism: A map of the intervention literature. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 35(3–4), 63–79.

Cera, R. (2015). National legislations on inclusive education and special educational needs of people with autism in the perspective of Article 24 of the CRPD. In V. D. Fina & R. Cera (Eds.), Protecting the rights of people with autism in the fields of education and employment: International, European and National Perspectives (pp. 79–108). Springer Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13791-9

Children and Families Act. (2014). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/6/contents/enacted. Accessed 22 Oct 2022

Connor, M. (1998). A review of behavioural early intervention programmes for children with autism Michael Connor. Educational Psychology in Practice, 14(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/0266736980140206

Connor, M. (2000). Asperger syndrome (autistic spectrum disorder) and the self-reports of comprehensive school students. Educational Psychology in Practice, 16(3), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/713666079

Cook, A., Ogden, J., & Winstone, N. (2016). The experiences of learning, friendship and bullying of boys with autism in mainstream and special settings: A qualitative study. British Journal of Special Education, 43(3), 250–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12143

Cook, A., Ogden, J., & Winstone, N. (2018). Friendship motivations, challenges and the role of masking for girls with autism in contrasting school settings. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(3), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2017.1312797

Cremin, K., Healy, O., Spirtos, M., & Quinn, S. (2021). Autism awareness interventions for children and adolescents: A scoping review. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 33, 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-020-09741-1

Cridland, E. K., Jones, S. C., Caputi, P., & Magee, C. A. (2014). Being a girl in a boys’ world: Investigating the experiences of girls with autism spectrum disorders during adolescence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(6), 1261–1274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1985-6

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP Qualitative Checklist. Retrieved September 3, 2019, from Online website: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf. Accessed 17 Oct 2019

Department for Education. (2014). Special educational needs in England: January 2014. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/362704/SFR26-2014_SEN_06102014.pdf. Accessed 27 May 2020

Department for Education. (2015a). Area guidelines for SEND and alternative provision. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/719176/Building_Bulletin_104_Area_guidelines_for_SEND_and_alternative_provision.pdf. Accessed 27 May 2020

Department for Education. (2015b). Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/398815/SEND_Code_of_Practice_January_2015.pdf. Accessed 27 May 2020

Dillon, G. V., Underwood, J. D. M., & Freemantle, L. J. (2016). Autism and the U.K. secondary school experience. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31(3), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357614539833

Education Act. (1981). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1981/60/enacted

Education Act. (2011). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2011/21/contents/enactedT

Elsabbagh, M., Divan, G., Koh, Y. J., Kim, Y. S., Kauchali, S., Marcín, C., … Fombonne, E. (2012). Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Research, 5(3), 160–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.239

Emam, M. M., & Farrell, P. (2009). Tensions experienced by teachers and their views of support for pupils with autism spectrum disorders in mainstream schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 24(4), 407–422. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ858332&site=ehost-live&authtype=ip,uid

Falkmer, M., Granlund, M., Nilholm, C., & Falkmer, T. (2012). From my perspective - Perceived participation in mainstream schools in students with autism spectrum conditions. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 15(3), 191–201. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2012.671382

Ferrari, M., & Matthews, W. S. (1983). Self-recognition deficits in autism: Syndrome-specific or general developmental delay? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 13(3), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01531569

Forlin, C., Watkins, A., & Meijer, C. (2016). Implementing inclusive education: Issues in bridging the policy-practice gap. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities (2023). Learning difficulties. https://www.learningdisabilities.org.uk/learning-disabilities/a-to-z/l/learning-difficulties. Accessed 9 May 2023

Goodall, C. (2018). Inclusion is a feeling, not a place: A qualitative study exploring autistic young people’s conceptualisations of inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1523475

Goodall, C. (2019). “There is more flexibility to meet my needs”: Educational experiences of autistic young people in mainstream and alternative education provision. Support for Learning, 34(1), 4–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12236

Goodall, C., & MacKenzie, A. (2019). Title: What about my voice? Autistic young girls’ experiences of mainstream school. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(4), 499–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2018.1553138

Gray, C., & Donnelly, J. (2013). Unheard voices: The views of traveller and non-traveller mothers and children with ASD. International Journal of Early Years Education, 21(4), 268–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2013.842160

Grima-Farrell, C. R., Bain, A., & McDonagh, S. H. (2011). Bridging the research-to-practice gap: A review of the literature focusing on inclusive education. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 35(2), 117–136.

Handleman, J. S., Harris, S. L., & Martins, M. P. (2005). Helping children with autism enter the mainstream (pp. 1029–1042). Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470939352.ch14

Hebron, J., & Bond, C. (2017). Developing mainstream resource provision for pupils with autism spectrum disorder: Parent and pupil perceptions. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(4), 556–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2017.1297569

Holt, L., Lea, J., & Bowlby, S. (2012). Special units for young people on the autistic spectrum in mainstream schools: Sites of normalisation, abnormalisation, inclusion, and exclusion. Environment and Planning A, 44(9), 2191–2206. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44456

Huang, A. X., Hughes, T. L., Sutton, L. R., Lawrence, M., Chen, X., Ji, Z., & Zeleke, W. (2017). Understanding the self inindividuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD): a review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1422. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01422

Humphrey, N., & Lewis, S. (2008a). “Make me normal”: The views and experiences of pupils on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 12(1), 23–46. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ782106&site=ehost-live&authtype=ip,uid

Humphrey, N., & Lewis, S. (2008b). What does “inclusion” mean for pupils on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools? Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 8(3), 132–140. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ815140&site=ehost-live&authtype=ip,uid

Joshi, G., Petty, C., Wozniak, J., Henin, A., Fried, R., Galdo, M., … Biederman, J. (2010). The heavy burden of psychiatric comorbidity in youth with autism spectrum disorders: A large comparative study of a psychiatrically referred population. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(11), 1361–1370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0996-9

Kasari, C., Dean, M., Kretzmann, M., Shih, W., Orlich, F., Whitney, R., … King, B. (2016). Children with autism spectrum disorder and social skills groups at school: a randomized trial comparing intervention approach and peer composition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(2), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12460

Kelly, C., Sharma, S., Jieman, A. T., & Ramon, S. (2022). Sense-making narratives of autistic women diagnosed in adulthood: A systematic review of the qualitative research. Disability & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2022.2076582

Kenyon, S. (2014). Autism in pink: Qualitative report. Lifelong Learning Programme. Retrieved from http://www.autisminpink.net/. Accessed 28 June 2020

Kirkbride, L. (1999). I’ll go first: The planning and review toolkit for use with children with disabilities. London: Children’s Society.

Knight, A., Petrie, P., Zuurmond, M., & Potts, P. (2009). “Mingling together”: Promoting the social inclusion of disabled children and young people during the school holidays. Child and Family Social Work, 14(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00577.x

Koegel, L. K., Vernon, T. W., Koegel, R. L., Koegel, B. L., & Paullin, A. W. (2012). Improving social engagement and initiations between children with autism spectrum disorder and their peers in inclusive settings. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14(4), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300712437042

Koegel, R., Kim, S., Koegel, L., & Schwartzman, B. (2013). Improving socialization for high school students with ASD by using their preferred interests. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2121–2134.

Landor, F., & Perepa, P. (2017). Do resource bases enable social inclusion of students with Asperger syndrome in a mainstream secondary school? Support for Learning, 32(2), 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12158

Mantzalas, J., Richdale, A. L., Adikari, A., Lowe, J., & Dissanayake, C. (2022). What is autistic burnout? A thematic analysis of posts on two online platforms. Autism in Adulthood, 4(1), 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2021.0021

Matson, J. L., Rivet, T. T., Fodstad, J. C., Dempsey, T., & Boisjoli, J. A. (2009). Examination of adapative behavior differences in adults with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(6), 1317–1325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2009.05.008

Mayton, M. R. (2005). The quality of life of a child with Asperger’s disorder in a general education setting: A pilot case study. International Journal of Special Education, 20(2), 85–101.

McFayden, T. C., Putnam, O., Grzadzinski, R., & Harrop, C. (2023). Sex differences in the developmental trajectories of autism spectrum disorder. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 10, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-023-00270-y

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ (online), 339(7716), 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Morán, M. L., Hagiwara, M., Raley, S. K., Alsaeed, A. H., Shogren, K. A., Qian, X., Gómez, L. E., & Alcedo, M. A. (2021). Self-determination of students with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 33, 887–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-020-09779-1

Morris, S., O’Reilly, G., & Nayyar, J. (2021). Classroom-based peer interventions targeting autism ignorance, prejudice and/or discrimination: A systematic PRISMA review. International Journal of Inclusive Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1900421

Moyse, R., & Porter, J. (2015). The experience of the hidden curriculum for autistic girls at mainstream primary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(2), 187–201. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1056772&site=ehost-live&authtype=ip,uid

Myles, O., Boyle, C., & Richards, A. (2019). The social experiences and sense of belonging in adolescent females with autism in mainstream school. Educational & Child Psychology, 36(4), 8–21.

O’Hagan, S., & Hebron, J. (2017). Perceptions of friendship among adolescents with autism spectrum conditions in a mainstream high school resource provision. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(3), 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2016.1223441

Parish, N., Bryant, B., & Swords, B. (2018). Have we reached a ‘tipping point’? Trends in spending for children and young people with SEND in England. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ce55a5ad4c5c500016855ee/t/5d1cdad6b27e2700017ea7c9/1562172125505/LGA+HN+report+corrected+20.12.18.pdf. Accessed 5 Apr 2020

Roberts, J., & Simpson, K. (2016). A review of research into stakeholder perspectives on inclusion of students with autism in mainstream schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(10), 1084–1096. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1145267

Rynkiewicz, A., Schuller, B., Marchi, E., Piana, S., Camurri, A., Lassalle, A., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2016). An investigation of the “female camouflage effect” in autism using a computerized ADOS-2 and a test of sex/gender differences. Molecular Autism, 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-016-0073-0

Saggers, B., Hwang, Y.-S., & Mercer, K. L. (2011). Your voice counts: Listening to the voice of high school students with autism spectrum disorder. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 35(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajse.35.2.173

Sciutto, M., Richwine, S., Mentrikoski, J., & Niedzwiecki, K. (2012). A qualitative analysis of the school experiences of students with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 27(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357612450511

Shochet, I., Wurfl, A., Orr, J., Kelly, R., Saggers, B., & Carrington, S. (2021). School connectedness to support student mental health and wellbeing. In S. Carrington, B. Saggers, K. Harper-Hill, & M. Whelan (Eds.), Supporting students on the autism spectrum in inclusive schools (c. 2). London: Routledge.

Siegel, M. (2018). The severe end of the spectrum: Insights and opportunities from the Autism Inpatient Collection (AIC). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 3641–3646.

South, G., & Sunderland, N. (2022). Finding their place in the world: What can we learn from successful autists’ accounts of their own lives? Disability and Society, 37(2), 254–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1816903

Special Educational Needs and Disability Act. (2001). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2001/10/contents. Accessed 22 Oct 2022

Strain, P. S. (1983). Generalization of autistic children’s social behavior change: Effects of developmentally integrated and segregated settings. Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disablities, 3(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0270-4684(83)90024-1

Symes, W., & Humphrey, N. (2010). Peer-group indicators of social inclusion among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools: A comparative study. School Psychology International, 31(5), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034310382496

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of inter-group conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of inter-group relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA.

The Warnock Report. (1978). Department of Education and Science Special Educational Needs: Report of the committee of enquiry into the education of handicapped children and young people. London: HMSO.

Tobias, A. (2009). Supporting students with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) at secondary school: A parent and student perspective. Educational Psychology in Practice, 25(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360902905239

Tomlinson, C., Bond, C., & Hebron, J. (2021). The mainstream school experiences of adolescent autistic girls. European Journal of Special Needs Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2021.1878657

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for action on special needs education. Retrieved from https://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/Salamanca_Statement_1994.pdf. Accessed 12 Apr 2020

UNESCO. (2005). Guidelines for inclusion: Ensuring access to education for all. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000140224. Accessed 12 Apr 2020

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Article 24 - Education. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html. Accessed 12 Oct 2022

Waddington, E. M., & Reed, P. (2006). Parents’ and local education authority officers’ perceptions of the factors affecting the success of inclusion of pupils with autistic spectrum disorders. International Journal of Special Education, 21(3), 151–164.

Warren, A., Buckingham, K., & Parsons, S. (2020). Everyday experiences of inclusion in primary resourced provision: The voices of autistic pupils and their teachers. European Journal of Special Needs Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1823166

Whitaker, P. (2007). Provision for youngsters with autistic spectrum disorders in mainstream schools: What parents say - and what parents want. British Journal of Special Education, 34(3), 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2007.00473.x

Williams, E. I., Gleeson, K., & Jones, B. E. (2019). How pupils on the autism spectrum make sense of themselves in the context of their experiences in a mainstream school setting: A qualitative metasynthesis. Autism, 23(1), 8–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317723836

Wolfensberger, W. (1983). Social role valorization: A proposed new term for the principle of normalization. Mental Retardation, 21(6), 234–239.

Acknowledgements

The authors did not receive support from any organisation for the submitted work.

The research was conducted in the UK in part fulfilment of the first author’s doctoral degree in clinical psychology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shama El-Salahi had the idea for this article and led each stage of the work; she performed the literature search, article screening, and data analysis, and she wrote the article. Zahra Khaki acted as a second reviewer during the article screening and data analysis stages to obtain measures of inter-rater reliability. Reena Vohora supervised the work and acted in a consultatory role during all stages, including helping to shape the idea for this article, resolving disagreements during the article screening and data analysis stages, and advising on theme development.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical approval and informed consent were not required as the research did not involve human participants.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions