Abstract

School buses facilitate access to education for many children. This research aimed to systematically review factors associated with safe school bus transportation for children with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). Searches of 5 databases, combining terms denoting NDDs and school buses, for English publications since 2000, yielded only 12 relevant articles among 1524 records. Literature was limited to parent-based studies, guidelines, reviews or commentaries. There was scant attention to the immediate roles of bus drivers and aides. Literature recommendations included increased attention to the needs of children with NDDs and improved communication, collaboration, support and training across all key stakeholders, particularly to improve implementation of individual child safety plans. Further research is needed on this critical support service for many families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Safe access to education is an important consideration for all children. Research has highlighted that individual physical and/or cognitive barriers frequently reduce participation in active school travel (Ross & Buliung, 2018) or driving (Lindsay, 2017). Consequently, children with disabilities can continue to be dependent on being transported by others to access education (Feeley et al., 2015). School bus transportation services provide one such option and can offer considerable support for families with high-need children, although trust in their safety and bus staff capacity to meet or manage the individual needs of their child can lead to reluctance to take up such services; not unfounded concerns (Angell & Solomon, 2018).

The present research was undertaken in Australia, where the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, 2018) has found that children with disability require the greatest assistance with cognitive or emotional activities (59.3%), communication (38.2%) and mobility (36.1%). However, the ABS also found correspondingly low levels of support provided through special tuition (36.8%), a counsellor or disability support person (23.2%) and, in particular, special transport arrangements (4.0%). This highlights a gap between the needs of a child with a disability for mobility and the limited support available (ABS, 2018). With the increasing global focus for children with disabilities to access education (e.g. Foreman, 2009; Shogren, 2017; Tsakanikos & McCarthy, 2014), this research sought to understand international insights and learning regarding the physical accessibility to education for children with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs).

NDDs is a broad category comprising disorders that are characterised by early-onset deficits of variable severity across personal, social, academic or occupational functioning, such as intellectual disability, autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM] 5th edition; APA, 2013). Recent Nordic research found the prevalence rate of NDDs was found to be the highest presenting condition in child and adolescent mental health services (Hansen et al., 2018), with prevalence similarly high in Australia. About one in every 22 (4.5%) of the 4.6 million children in Australia in 2018 had an intellectual disability, with ‘autism and related disorder’ the most commonly reported disability at 26.8% (ABS, 2018).

Children with NDDs such as those on the autism spectrum or those with lower expressive language ability, particularly younger children, are found to engage in more frequent problem behaviours compared to older children or children with more expressive language skills (Maskey et al., 2013). Often, the mismatch between the environment and needs of such children can increase the prevalence of challenging behaviours. It is common therefore for children with NDDs to face additional challenges in relation to transportation options due to a variety of reasons.

Firstly, children with NDDs may experience difficulties in perspective-taking, which may manifest as a lack of understanding that drivers need to orientate to the various demands of traffic situations (Falkmer et al., 2004). Secondly, some children with NDDs also have sensory processing issues that affect their ability to tolerate harness systems (Yonkman et al., 2013). Thirdly, children may experience magnified anxiety under certain external conditions (e.g. unpredictable journey disruptions) and become emotionally unregulated (e.g. experience emotional ‘meltdowns’), making it difficult for them to respond to behaviour support techniques (Lindsay, 2017). These challenges may prompt children with NDDs to attempt to release themselves from restrained booster seats or seatbelts and disturb or distract the driver with aggressive, self-injurious or disruptive behaviour during travel, e.g. attacking drivers/passengers, opening vehicle doors, head banging, hitting themselves, holding their breath and rocking back and forth forcefully (Falkmer et al., 2004; Yonkman et al., 2013). More specific concerns have been raised by parents of children with autism, such as the child’s reduced capacity to adapt their behaviour to the situation, including when travelling with unknown drivers or passengers, especially for younger children and those experiencing difficulties with social interactions and communication (Falkmer et al., 2004).

School Bus Transportation of Children with NDDs in Queensland, Australia

In Australia, the funding and responsibility for transportation is split between the federal, state and local governments, with each state managing the transportation needs of children with disability. Within the state of Queensland (the more specific location of the current research), the Queensland Human Rights Act 2019 was developed to ensure no discrimination (e.g. physical and/or economical) of children with disability on any grounds (Jensen et al., 2019). However, the exclusion of dedicated school bus services to meet the requirements in the Transport Standards of the Disability Standards for Accessible Public Transport in Australia demonstrates reduced emphasis in facilitating physical access for children with disability to education (DIRD, 2002). With transportation one of the many factors included in the decision-making process of choosing a suitable school, parents of children with disabilities often report experiencing uncertainty in making this difficult but necessary decision for their children (Mann et al., 2015).

The Queensland Government provides support through the Queensland School Transport Assistance scheme whereby parents of children with disabilities can qualify for contract transport to a state or specific-purpose school with the shortest trafficable route. A support plan confirming that the child has transportation needs demonstrably different to those of their typically developing same-aged peers is required for students who are enrolled in a non-state school (QCEC, 2020). The provision of this transport assistance via contract buses helps to bridge the gap between the child with disability’s need for transportation and the difficulty in negotiating public transport services.

More broadly, in encouraging appropriate behaviour on buses and consistent management of behaviours for all school students travelling on buses, the Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads (TMR, 2013) has released the Code of Conduct for School Students Travelling on Buses (herein referred to as the Code of Conduct, or Code). This universal guide includes the roles, rights and responsibilities for nominated key stakeholders, namely, students, parents/carers, bus drivers, bus operators, schools, TMR and conveyance committees. In addition, it states the step-by-step procedures for drivers and bus operators in responding to each of several categories of behaviour breach. Positively, the proactive provision of information and travel strategies by parents/carers and schools, as well as additional considerations for investigating misconduct, are stipulated. However, the Code does not specify any other forms of targeted support for students with disabilities. The lack of inclusion of bus aides as a stakeholder group, where applicable, is one clear such example. Bus aides are required on school buses carrying children with disabilities as defined by the Queensland Government for both public and private schemes. Therefore, guidelines on this important role are apt for inclusion in the Code.

School Bus Safety Concerns for Children with NDDs

In-vehicle distractions have been found to impact drivers’ ability to maintain speed, and preparedness to react to unexpected hazards, and to increase use of safety short-cuts (Horberry et al., 2006; Salmon et al., 2011; Zohar & Lee, 2016). School bus drivers have previously reported being anxious about being distracted by disruptive child behaviours, as additional cognitive resources are required to watch the road while ensuring the safety of all passengers on the bus (Zohar & Lee, 2016). While the identification of the rights, roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder in codes of conduct regarding bus transport services (such as the Queensland Code) aims to contribute to safe and responsible travel, there are differentiated findings on the safety of school bus transportation between neurotypical children and children with NDDs, with the latter experiencing higher crash fatalities and injury rates (Yang et al., 2009). In one extreme example, Jeremy, a 6-year-old special needs child, died in 2010 after jumping from a moving school bus in Baltimore County (ASU, 2012). His support plan, which included compulsory use of a safety vest, was not followed through by the Baltimore city school system or the contractor of the school bus service (ASU, 2012). This tragic incident brings a sobering message highlighting the transportation needs and the level of support required on the bus for some children with NDDs.

Theoretical Lens—Bronfenbrenner’s Model

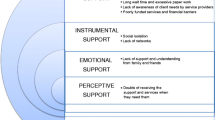

This research adopted a social ecological model by Bronfenbrenner (1979) to explore factors associated with safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (represented in Fig. 1) proposes that individuals are players within a larger social network that is made up of several components including micro-, meso-, exo-, macro- and chrono-systems. According to this theory, one has to consider both the inherent qualities of children with NDDs and their interactions with the characteristics of the environment to appreciate the complexity involved in the transportation for children with NDDs. In the present research, key stakeholders in the child with NDD’s environment of interest (safe school bus transportation) were identified as bus drivers, bus aides, parents, schools and bus companies (Fig. 1).

Illustration of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model, in the context of safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs. Note: The central image provides various depictions of a child with NDD in the middle of concentric circles of (interactive) influence from each level of the ecological systems

Study Purpose, Significance and Overarching Research Questions

The overarching purpose of this research was to explore factors associated with safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs in order to inform potential improvements to policy and practice. While the importance of collaboration between all stakeholders in managing student behaviour on buses is appreciated theoretically (Lindsay, 2017), a preliminary search found minimal research on stakeholder perspectives beyond parents in the transportation of children with NDDs. Therefore, a systematic review of research into factors associated with safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs was undertaken. The overarching research questions were as follows:

-

What is the evidence base on factors associated with safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs?

-

More specifically, what are the child-, bus driver–, bus aide–, parent-, school- or bus company–related factors associated with safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs?

Methods

A systematic was conducted in September 2020.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Due to the anticipated small number of relevant studies, all peer-reviewed papers with all types of methodological designs were included, including reviews and research-based position statements, with media sources (e.g. newspaper articles, magazines) excluded. Papers were limited to those in English, due to researcher limitations, and to those published from the year 2000 onwards, to account for NDD terminology variations. (Prior to the year 2000, vaguely worded guidelines and lack of explicit operational criteria of ‘pervasive developmental disorder – not otherwise specified’ created confusion among professionals (Feinstein, 2010). When the 1994 edition of the DSM (fourth edition) underwent a text revision in 2000, the definition of autism was more clearly defined, with a spectrum ranging from mild to severe.)

Studies were excluded if they focused on general public bus transportation (i.e. non-school-related); did not clearly identify that buses were used for school transportation for children with NDDs; or focused on children with physical disabilities, intellectual disabilities, vision difficulties and/or hearing difficulties that were not comorbid conditions with NDDs.

Literature Search

Electronic databases employed were Education Resources Information Center, The Cochrane Library, Scopus, EMBASE, ProQuest Central and Web of Science. Search terms included a combination of ‘school bus’ or ‘special education bus’ and terms denoting NDDs, such as ‘developmental disability’, ‘intellectual impairment’ or ‘autism’ (Table 1). Reference lists of selected full papers also were examined for potentially relevant articles and all selected papers were entered into Connectedpapers.com to identify any further potentially relevant papers.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers (first and second author) independently conducted the searches and screened resulting records, first by titles to remove studies clearly not within topic, and then by abstracts. Agreed full texts were retrieved and further independently assessed, with any disagreement between the two reviewers resolved through discussion with the third reviewer (third author). Reasons for excluding studies at the full text stage were recorded.

Each included record was then summarised by the first author using a standard data extraction form and assessed for quality using the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (quantitative studies) and Critical Appraisal Skills Program checklist (qualitative studies). The second author reviewed the extraction ratings and discrepancies were resolved on discussion (without requiring mediation).

Results

Figure 2 presents the outcomes of the systematic search strategy employed according to PRISMA guidelines. In total, 1524 records were identified. After duplicates were removed, the titles and abstracts of 1357 records were screened. Arbitration by the third reviewer was required for 7 records (2 included, 5 excluded). Reasons for exclusions are summarised in Table 2.

A final total of 12 studies was included, as summarised in Tables 3 (details) and 4 (findings and implications). As studies were expected to be heterogenous, a narrative synthesis of the findings from the included studies was structured around the contributing factors and Bronfenbrenner’s social ecological model.

Factors Related to Safe School Bus Transportation

The Child

Four references were relevant to the child—innermost circle of Bronfenbrenner’s model: Table entries 4, 6, 8 and 10.

Bullying was identified as a factor associated with safe travel in the ‘unstructured social situation’ of transportation for children with NDDs in England, especially those who exhibited behavioural difficulties and were older (Hebron & Humphrey, 2014, 626). The researchers recommended that both the individual behaviours of the child and the context of the school bus environment be simultaneously considered in understanding the experiences of bullying for children with NDDs. Child-specific supports regarding safe bus transportation ranged from pharmaceutical to behavioural and educational. In the USA, including medication within a child-specific behaviour management approach was recommended to support safe transportation of children with ADHD, as well as behavioural therapy for those with coexisting mental health conditions (Rappley, 2005). A Swedish interactive electronic educational tool to guide both children and bus drivers on specific safe behaviours during their school bus travel was found to benefit children with NDDs, albeit it was concluded that they might be slightly more cautious in embracing such a programme than their neurotypical peers (Falkmer et al., 2013). Use of person-centred planning and a health action plan—one that involves consultation with the child and other key stakeholders—was demonstrated to facilitate safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs in one case study in Ireland (Ryan & Carey, 2008), offering a potential approach to address the other identified factors within this individual level of the model.

Parents

Seven references were relevant to parents—second circle of Bronfenbrenner’s model: Table entries 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 10.

Parents are one of the most important and motivated stakeholder groups within the child’s circle of support. Correspondingly, relatively more literature was identified on the perspectives of parents than other stakeholders in understanding factors associated with safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs. In one study, a large proportion of surveyed parents of children with autism in Sweden worried about school bus safety (Falkmer & Gregersen, 2002). Concerns, including those reported in the other selected studies, focused on the child’s sensory and communication difficulties, bus drivers’ or bus aides’ inadequate knowledge of the child’s disability and support needs, and a lack of compliance with safety recommendations (Downie et al., 2020; Falkmer & Gregersen, 2002; Falkmer et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2014; Tiernan et al., 2013). These concerns could be generally associated with lack of knowledge of school transport regulations and standards and the limited involvement of parents in discussing child-specific needs (Falkmer & Gregersen, 2002; Falkmer et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2014; Ryan & Carey, 2008; Tiernan et al., 2013). One way to facilitate safe school bus transportation is for parents to be active participants in the planning and sharing information on their child’s needs to other relevant stakeholders (O’Neil et al., 2018).

Bus Drivers and Bus Aides

Seven references were relevant to bus transport staff—second circle of Bronfenbrenner’s model: Table entries 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11 and 12.

While much of the literature on children with NDDs focused on parents’ views, scant literature explored the perspectives of bus drivers and bus aides, even though they are the key intermediaries of safety in such school transportation. Concerns relating to bus aides raised by parents included the following: bus aides not attending to their children; inappropriate gender match between bus aide and student; high incidence of bus aide turnover; lack of bus aides; and too many students to one bus aide (Graham et al., 2014). Further, there was general consensus within existing literature for increased critical attention to research and practice, including clarifying roles, and responsibilities and training of bus drivers and bus aides, as well as their inclusion in the transportation plans of children (Falkmer & Gregersen, 2002; Falkmer et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2014; O’Neil et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2020; Thomas, 2004; Tiernan et al., 2013).

School

Five references were relevant to the school—second circle of Bronfenbrenner’s model: Table entries 1, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

The school plays an important role in a child’s life following the introduction of compulsory education. As children with NDDs are found to travel to school more frequently than for other leisure activities, it is imperative for the school to ensure that best-practice guidelines surrounding use of appropriate restraints and training of bus aides are adhered to on school vehicles (Downie et al., 2020). In addition to parents and family, teachers and school staff are often viewed as the other protective adults throughout the child’s development. Their additional perspectives and interactions with children with NDDs are helpful in addressing blind spots surrounding transportation safety issues, such as factors associated with bullying on school buses (Hebron & Humphrey, 2014). Therefore, the participation of teachers and school transportation staff in the development of the transportation portion of support plans and annual training programmes was argued to facilitate greater awareness and implementation of safety practices (O’Neil et al., 2018; Rappley, 2005; Ross et al., 2020).

Bus Operator/Transport Provider

Three references were relevant to bus operators—third circle of Bronfenbrenner’s model: Table entries 5, 7 and 11.

Even though the bus operators/transport providers do not directly interact with children with NDDs, the review confirmed they play an important role in coordinating information relevant for safe school bus transportation. The involvement of this group of stakeholders can facilitate safe school bus transportation through a two-pronged approach, guided by disability rights policy and legislation to ensure equity in access to education through supported bus travel. Firstly, they can communicate the bus transport procedures and guidelines, including safe procedures for embarking on and disembarking from the school bus, procedures to ensure no child is left on the bus and preparation for emergency evacuations (O’Neil et al., 2018). Secondly, they can support the logistical aspects of transportation, such as providing employee inductions and addressing scheduling and equipment problems that might compromise safe bus transportation (Graham et al., 2014; Thomas, 2004).

Representation of Bronfenbrenner’s Model

The concentric circles of the Bronfenbrenner’s social ecological model indicate bi-directional proximal and distal influences from other circles of influence on the child’s development. Mapping the identified studies to levels of the model allows identification of the focus and the gaps within current literature regarding safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs. The interconnectivity of people and organisations across the various levels resulted in categorising each of the 12 studies to more than one level of influence. This outcome alone further supports the general conclusions of the need for improved interactions between the various stakeholders.

Overall, there were three studies on the individual level, eight on the level of the microsystem, five on the mesosystem, three on the exosystem and also three on the macrosystem. Most of the studies within the microsystem and exosystem involved the perspectives of parents and their concerns of the school bus transportation. Only one study focused on the perspective of the direct bus transportation staff (i.e. bus aides) regarding transporting children with NDDs on the school bus, confirming this as one of the critical gaps in current literature.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to understand the factors associated with safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs. To accomplish this, a systematic review was conducted to provide a broad understanding of the issues explored relative to the multiple layers or systems within Bronfenbrenner’s social ecological model. The findings are discussed relative to each of these layers, including future research needs and implications for relevant codes of conduct, such as that in Queensland, to address additional needs for children with NDDs when travelling on school buses.

Individual Level—The Child

The results from the systematic review noted that some children with NDDs have difficulties in their social interactions, coping with the confined space, uncomfortable temperature and the legal requirements of using seatbelts on a school bus (Falkmer et al., 2004; Yonkman et al., 2013). Their needs for structure/routine, their difficulties in emotional and behavioural regulation, and communication were identified as important factors influencing the externalising behaviours displayed during bus travel. The severity of these behaviours could also result in bullying behaviours by other passengers on board the school bus (Hebron & Humphrey, 2014).

While the literature suggested a range of pharmaceutical, behavioural and educational strategies to help reduce the occurrences of externalising behaviours on the school bus (Falkmer et al., 2013; Rappley, 2005), future research can consider how a more comprehensive and systemic approach to supports, taking into account multi-level stakeholders (as per Bronfenbrenner’s model), can be achieved through increased professional development and training and consultation with key stakeholders to more effectively support the needs of this cohort of children (Falkmer et al., 2004; Goldin & McDaniel, 2018; Thompson & Emira, 2011). Figure 3 provides a summary of influences on safe bus travel and recommendations and implications for transporting children with NDDs based on the results of this study that warrant further consideration. Recognising the limited number of studies identified, this discussion also includes some additional recommendations that warrant further consideration beyond those in Fig. 3.

Microsystem

The bus driver and bus aides are the key personnel within the child’s immediate environment of the school bus. Driver distraction can be broadly understood as a trigger that draws one's attention from the task of driving (Young & Lenné, 2010). The risk of distraction could be considered particularly significant in this domain where drivers are compelled, as part of their job, to perform additional secondary tasks (e.g. ensuring in-vehicle safety of children) over and above the primary task of driving the vehicle.

While not specifically identified in the limited final articles of the review, another potential impact on both bus driver and bus aide attention to safety concerns worthy of further consideration is fatigue. Fatigue can be manifested in many ways, such as drivers’ reduced attention, slower reactions and poorer steering (Sluiter, 1999). Fatigue, both general and work-related, has been consistently found to mediate the relationship between job strain and risky driving, and between social support and risky driving among bus drivers (Useche et al., 2017). Work-related fatigue, operationalised by Veldhoven and Broersen (2003), is short-term accumulated fatigue from insufficient recovery from work that bridges the stage between normal work-related effort and chronic fatigue (‘burnout’). One of the effects of such occupational stressors on driving includes fatigue-related crashes (Rowland et al., 2007).

There is currently no readily identifiable literature around the role of distractions or fatigue involved in transporting children with NDDs either with bus drivers or with bus aides. Therefore, future research can consider how such factors might impact and need to be addressed to improve safe bus travel.

Mesosystem

This section focuses on the interactional patterns among stakeholders in the microsystems. These include linkages between the bus driver and bus aide, between the bus transport staff and the school, and between the bus transport and the parents.

Results from the systematic review noted that collaboration between bus transport staff is key to effectively managing challenging behaviours (Ross et al., 2020; Tiernan et al., 2013). Previous research in the USA found that many bus drivers expressed their dissatisfaction with bus aides for their lack of assistance in breaking up disruptive fights on the bus (Restrepo et al., 2015). It is important for bus transport staff to be equipped with necessary positive behaviour support skills to effectively de-escalate behaviours and reduce distractions for safe transportation (Downie et al., 2020). Future in-depth research will be helpful in exploring bus drivers’ and bus aides’ perspectives and potential barriers to effective collaboration.

While school buses transport children to and from school, school representatives play a key role in supporting evidence-based practices that address the children’s transport needs. The results of this study highlighted some of the positive impacts school involvement could have in supporting bus drivers and bus aides during school bus transportation of children with NDDs (e.g. developing and understanding of the children’s needs and challenges: Ryan & Carey, 2008; Thomas, 2004). However, the provision of adapted classroom support strategies, such as having volunteer adult escorts and using a ‘buddy system’ to increase monitoring of students’ behaviours (e.g. de Lara, 2008, 63), might be less feasible to implement on the school bus for children with NDDs (O’Neil et al., 2018; Tiernan et al., 2013). Therefore, it is important for schools to organise context-specific behavioural support training to meet the unique transportation needs of children with NDDs on the school bus.

Further, results from the systematic review revealed that more research had been conducted examining parents’ perspectives on the bus transportation staff than other connections between stakeholders within the mesosystem. Some of the parents’ worries about bus transportation staff included an inadequate knowledge of their child’s disability, inability to communicate with the child and poor compliance with safety recommendations during school bus transportation (Angell & Solomon, 2018; Falkmer et al., 2004). Therefore, better communication can be made possible by expanding the use of supports, such as the guidance tools detailed in Forsman and Falkmer (2005). Such supports can allow parents and other stakeholders to have accurate and consistent information of the school transport system code and processes, thus facilitating improved communication and cooperation in addressing the unique transportation needs of each child (Forsman & Falkmer, 2005). While there was no specific study resulting in an overlap between the parent–child circle and school circle in Fig. 3, tools such as this and other content relevant to transportation could feature in the child’s individualised education plan (IEP). More attention is warranted in such parent–child-school associations with bus aides in this system level.

Exosystem

This section discusses how the environment, including the bus operator in the current context, whom the child has no direct interaction with can still have an impact on their safe school bus transportation. According to the Queensland Code of Conduct, bus operators are responsible for providing bus transport staff with training to manage the behaviour of students, as well as ensuring compliance in delivering the Code’s indicated procedures for managing incidents of student misconduct (TMR, 2014). A perceived lack of support from bus operators was reported by bus drivers in previous Queensland research in which 80% did not report incidents (TMR, 2017). Identified reasons included the following: a perception that no actions would be taken about the incident; the incident was deemed not serious enough to report; concerns regarding being reprimanded/blamed for the incident; time-consuming paperwork; and uncertainty about the need for an incident to be reported. As such, it is likely that bus operators in Queensland would also require support in understanding and implementing the Code of Conduct procedures. When bus operators are able to clearly communicate the transportation guidelines and consistently provide support for bus incidents and misconducts, the bus transportation staff are likely to perceive less barriers when providing safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs (TMR, 2017).

Macrosystem

In the current context, this layer of Bronfenbrenner’s model addresses how external influences such as laws and political systems can have a significant influence on the safe transportation for children with NDDs. While laws and regulations are effective mechanisms for enabling large segments of the population to adopt safe transportation behaviours of children, they must be supported by an underlying ‘culture of safety’ where injury prevention becomes the social norm (Schieber et al., 2000, 130).

One suggestion from the literature regarding injury prevention is to pre-emptively provide behavioural interventions to children identified to exhibit challenging behaviours through the implementation of a tiered behavioural approach (O’Neil et al., 2018). Another consideration comes from the public transport authority in Western Australia, with its equivalent Code of Conduct detailing the additional roles and responsibilities of the bus aide in their behaviour management guidelines, thereby providing a more holistic wrap-around support for all students, including those with intellectual or emotional difficulties (PTASBS, 2015). These are as follows:

-

Bus aides are responsible to work in conjunction with the driver to devise and employ behaviour management strategies appropriate to the unique needs and capacities of each student.

-

Bus aides can expect training in behaviour management strategies and incident reporting procedures.

Contrasting Queensland and Western Australia Codes, together with the limited literature identified, suggests it is time for jurisdictions to review their respective codes of conduct and to attend to these issues to ensure the safety of children with NDDs (and likely those with other disabilities) requiring bus aide support.

Limitations

While the systematic review aimed to be comprehensive in identifying factors associated with safe school bus transportation for children with NDDs researched over the past two decades, no research was found on a number of key factors across the various levels of the Bronfenbrenner’s model (e.g. how fatigue has an impact on risky driving behaviours or bus aide inattention). This lack of findings could be attributed to the selection of databases and search terms used, including a limit to English language. However, given that additional steps were taken to review reference lists and to use Connectedpapers.com, as well as the focus on the most recent publications, it is unlikely that any major body of work was missed.

Conclusions

This research has provided valuable insights from behind the wheel regarding the behavioural manifestation of children with NDDs on the school bus and the range of factors associated with their safe school bus transportation. While a limited literature has focused on the perspectives of parents, there remains a substantial gap in the involvement and impact of other stakeholders, as identified using the Bronfenbrenner’s model: particularly, bus drivers and bus aides. Within the context of the school bus, these are the individuals with which children have the most direct, face-to-face contact in managing safety. These identified gaps in both research and applied practice of safe bus transportation for children with NDDs suggest that there is critical need for increased research attention to this subject, as well as review and revision of relevant codes of conduct. Future research must include the perspectives of other stakeholders, such as bus drivers and bus aides, so that better wrap-around preventive support—such as evidence-based improvements in training and support tools for greater communication and collaboration across stakeholders—is provided to ensure children with NDDs and their families can be assured that school bus travel is a safe transportation option in facilitating the child’s right to education.

References

ABS: Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Disability, ageing and carers: Summary of findings. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release. Accessed 25 Jan 2020.

APA: American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Publisher.

Angell, A. M., & Solomon, O. (2018). Understanding parents’ concerns about their children with autism taking public school transportation in Los Angeles County. Autism, 22(4), 401–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316680182

ASU: American School and University. (2012). 2010 death of special-education student prompts lawsuit against Baltimore district. Informa; August 23.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

de Lara, E. W. (2008). Bullying and aggression on the school bus: School bus drivers’ observations and suggestions. Journal of School Violence, 7(3), 48–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220801955554

DIRD: Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development. (2002). Review of the disability standards for accessible public transport. https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/transport/disabilities/review/files/Review_of_Disability_Standards_for_Accessible_Public_Transport.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2020.

Downie, A., Chamberlain, A., Kuzminski, R., Vaz, S., Cuomo, B., & Falkmer, T. (2020). Road vehicle transportation of children with physical and behavioral disabilities: A literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 27(5), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2019.1578408

Falkmer, T., & Gregersen, N. P. (2002). Perceived risk among parents concerning the travel situation for children with disabilities. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 34(4), 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-4575(01)00053-7

Falkmer, T., Anund, A., Sörensen, G., & Falkmer, M. (2004). The transport mobility situation for children with autism spectrum disorders. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 11(2), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038120410020575

Falkmer, T., Horlin, C., Dahlman, J., Dukic, T., Barnett, T., & Anund, A. (2013). Usability of the SAFEWAY2SCHOOL system in children with cognitive disabilities. European Transport Research Review, 6(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12544-013-0117-x

Feeley, C., Deka, D., Lubin, A., & McGackin, M. (2015). Detour to the right place: A study with recommendations for addressing the transportation needs and barriers of adults on the autism spectrum in New Jersey. Rutgers University Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation. http://vtc.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Detour_to_the_Right_Place_Technical_Report_2015.pdf. Accessed 2 May 2020.

Feinstein, A. (2010). Chapter 7. Definition, diagnosis and assessment: A history of the tool. In A. Feinstein (Ed.), A history of autism: A conversation with the Pioneers (pp. 165–202). Wiley.

Foreman, P. (2009). Education of students with an intellectual disability research and practice. Information Age Publishing.

Forsman, Å., & Falkmer, T. (2005). Handbook guidance promoting a safe journey for children with disabilities - An evaluation. Transportation Research Part a: Policy and Practice, 40(9), 712–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2005.12.002

Goldin, J. T., & McDaniel, S. C. (2018). Reducing discipline and safety issues: A district-wide bus-PBIS Initiative. Beyond Behavior, 27(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074295618768447

Graham, B. C., Keys, C. B., McMahon, S. D., & Brubacher, M. R. (2014). Transportation challenges for urban students with disabilities: Parent perspectives. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 42(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2014.855058

Hansen, B. H., Oerbeck, B., Skirbekk, B., Petrovski, B. E., & Kristensen, H. (2018). Neurodevelopmental disorders: Prevalence and comorbidity in children referred to mental health services. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 72(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2018.1444087

Hebron, J., & Humphrey, N. (2014). Exposure to bullying among students with autism spectrum conditions: A multi-informant analysis of risk and protective factors. Autism, 18(6), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313495965

Horberry, T., Anderson, J., Regan, M. A., Triggs, T. J., & Brown, J. (2006). Driver distraction: The effects of concurrent in-vehicle tasks, road environment complexity and age on driving performance. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 38(1), 185–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2005.09.007

Jensen, M., Cassar, S., & Ketheeswaran, A. (2019). The Queensland Human Rights Act 2019: Key features of the law and potential impacts for children with disabilities at school. The University of Queensland. https://law.uq.edu.au/files/45472/UQ_PBC_publication_right_to_education_under_the_human_rights_act_2019_24_may_2019.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2020.

Lindsay, S. (2017). Systematic review of factors affecting driving and motor vehicle transportation among people with autism spectrum disorder. Disability and Rehabilitation, 39(9), 837–846. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2016.1161849

Mann, G., Cuskelly, M., & Moni, K. (2015). Choosing a school: Parental decision-making when special schools are an option. Disability & Society, 30(9), 1413–1427. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2015.1108182

Maskey, M., Warnell, F., Parr, J. R., Le Couteur, A., & McConachie, H. (2013). Emotional and behavioural problems in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(4), 851–859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1622-9

O’Neil, J., Hoffman, B. D., Quinlan, K. P., Burns, M., Denny, S., Ebel, B., Hirsh, M., Melzer-Lange, M., Powell, E., Schaechter, J., & Zonfrillo, M. R. (2018). School bus transportation of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics, 141(5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0513

PTASBS: Public Transport Authority School Bus Services, Western Australia. (2015). Behaviour management guidelines: For students travelling to school by government contract school bus. https://www.schoolbuses.wa.gov.au/Portals/2/SBS/Safety/Behavoiur%20Management%20Guidelines.pdf?ver=2019-03-21-133833-487. Accessed 3 Apr 2020.

QCEC: Queensland Education Catholic Commission. (2020). Non state school: Transport assistance scheme. http://www.schooltransport.com.au/check-your-eligibility/swd/. Accessed 3 Oct 2020.

Rappley, M. (2005). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352(2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.4274/tpa.46.27

Restrepo, M., Weinstein, M., & Reio, T. G. (2015). Job structure and organizational burnout: A Study of public school bus drivers, bus aides, mechanics, and clerical workers. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 30(3), 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2015.1027824

Ross, T., & Buliung, R. (2018). A systematic review of disability’s treatment in the active school travel and children’s independent mobility literatures. Transport Reviews, 38(3), 349–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2017.1340358

Ross, T., Bilas, P., Buliung, R., & El-Geneidy, A. (2020). A scoping review of accessible student transport services for children with disabilities. Transport Policy, 95, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.06.002

Rowland, B., Wishart, D., & Davey, J. (2007). The influence of occupational driver stress on work-related road safety: An exploratory review. Journal of Occupational Health Safety, 23(5), 459–468.

Ryan, B., & Carey, E. (2008). Introducing person-centred planning: A case study. Learning Disability Practice, 11(9), 12–20.

Salmon, P. M., Young, K. L., & Regan, M. A. (2011). Distraction “on the buses”: A novel framework of ergonomics methods for identifying sources and effects of bus driver distraction. Applied Ergonomics, 42(4), 602–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2010.07.007

Schieber, R. A., Gilchrist, J., & Sleet, D. A. (2000). Legislative and regulatory strategies to reduce childhood unintentional injuries. Future of Children, 10(1), 111–136. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602827

Shogren, K. A. (2017). Handbook of research-based practices for educating students with intellectual disability. Routledge.

Sluiter, J. K. (1999). The influence of work characteristics on the need for recovery and experienced health: A study on coach drivers. Ergonomics, 42(4), 573–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/001401399185487

Thomas, D. D. (2004). Use transportation as a related service. Intervention in School and Clinic, 39(4), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/10534512040390040701

Thompson, D., & Emira, M. (2011). “They say every child matters, but they don’t”: An investigation into parental and carer perceptions of access to leisure facilities and respite care for children and young people with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) or attention deficit, hyperactivity d. Disability and Society, 26(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.529667

Tiernan, B., Deacy, E., & McDonagh, D. (2013). Getting to school safely: Implications of school transport for children with special educational needs. REACH Journal of Special Needs Education in Ireland, 26(2), 118–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2015.1108182

TMR: Department of Transport and Main Roads, Queensland. (2013). Safe travel of school students: Guiding principles and stakeholder actions. http://www.tmr.qld.gov.au/~/media/Travelandtransport/School%20transport/Code%20of%20conduct/Managing%20student%20behaviour%20on%20buses%20package/SafeTravelSchoolStudentsGuidingPrinciples.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2020.

TMR: Department of Transport and Main Roads, Queensland. (2014). The code of conduct for school students travelling on buses: Supporting responsible and safe bus travel. https://translink.com.au/sites/default/files/assets/resources/travel-with-us/school-travel/code-of-conduct-for-students-travelling-on-buses.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2020.

TMR: Department of Transport and Main Roads, Queensland. (2017). Queensland Bus Driver Safety Review. https://translink.com.au/sites/default/files/assets/resources/about-translink/projects-initiatives/bus-driver-safety-review.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2020.

Tsakanikos, E., & McCarthy, J. (2014). Handbook of Psychopathology in Intellectual Disability Research, Practice, and Policy (1st ed.) [Online]. Springer New York.

Useche, S. A., Ortiz, V. G., & Cendales, B. E. (2017). Stress-related psychosocial factors at work, fatigue, and risky driving behavior in bus rapid transport (BRT) drivers. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 104, 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2017.04.023

Veldhoven, V. M., & Broersen, S. (2003). Measurement quality and validity of the “need for recovery scale”. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(SUPPL. 1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i3

Yang, J., Peek-Asa, C., Cheng, G., Heiden, E., Falb, S., & Ramirez, M. (2009). Incidence and characteristics of school bus crashes and injuries. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 41(2), 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2008.12.012

Yonkman, J., Lawler, B., Talty, J., O’Neil, J., & Bull, M. (2013). Safely transporting children with autism spectrum disorder: Evaluation and intervention. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67(6), 711–716. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2013.008250

Young, K., & Lenné, M. G. (2010). Driver engagement in distracting activities and the strategies used to minimise risk. Safety Science, 48, 326–332.

Zohar, D., & Lee, J. (2016). Testing the effects of safety climate and disruptive children behavior on school bus drivers performance: A multilevel model. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 95, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2016.06.016

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, L.Y.L., Senserrick, T. & Saggers, B. Behind the Wheel: Systematic Review of Factors Associated with Safe School Bus Transportation for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 11, 343–360 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-022-00341-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-022-00341-7