Abstract

We conducted a meta-analysis which included 16 sibling-mediated intervention studies that aims to utilize siblings to teach their brothers and sisters with autism spectrum disorder play skills, functional skills, or to decrease unwanted behaviors. In general, results across the studies show that sibling-mediated intervention has medium effect size and can be used as a method to improve many skills which include social and communication skills. Sibling-mediated intervention also facilitated maintenance and generalization of the targeted skills. The researchers discuss the findings and make suggestions for future investigations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has been defined as a severe neurodevelopmental disorder which causes considerable affliction in individuals, their family members, and the communities in which they live as a whole (Christensen et al. 2018). Over the years, estimates related to ASD have evolved and continue to raise concerns despite the geographical differences in its prevalence (Fombonne 2018; Xu et al. 2018). It was argued that interventions in the area of ASD that were deemed appropriate and effective are the ones that result from the principles of applied behavior analysis in that they are based on experimentations and provide treatment evidences (Wong et al. 2013). Interventions that use the techniques of applied behavior analysis have been described as processes during which the child or person diagnosed with ASD is shown a particular behavior of interest, instigating that individual to reproduce the displayed behavior and providing them with reinforcement upon completion of the desired behavior (Odom et al. 2010). For decades, a large number of different types of interventions have been implemented and utilized in diverse settings which encompass the use of electronics, such as video (Buggey 2012; Cardon 2012), the mediation of parents (McConachie and Diggle 2007; Green et al. 2010), the mediations of peers (Bene et al. 2014; Krebs et al. 2010; Whalon and Hanline 2008), and the inclusion of siblings (Jones and Schwartz 2004; Rayner 2011a).

Past investigations that attempted to assess normally developing siblings’ and peers’ contributions to improving social skills in others who have ASD found that these developmentally healthy children have the ability to learn and utilize behavior modification strategies to improve their social interactions with their friends or brothers and sisters who have ASD (Oppenheim-Leaf et al. 2012). In this light, many investigations have been conducted with siblings as mediators.

In a study conducted by Oppenheim-Leaf et al. (2012), the investigators first taught normally developing children several social behaviors which were in turn utilized to affect their siblings who were diagnosed with ASD whenever they play with them. Findings suggested that the three children diagnosed with ASD successfully learned the skills. In another study, in which the researchers assessed the effectiveness of a behavior change procedure, typically developing children were first trained and used as mediators. Results showed that the normally developing children learned to use the behavior change procedure very effectively to teach their brothers and sisters who were diagnosed with ASD, improving their conditions (Schreibman et al. 1983). Celiberti and Harris (1993) also measured the success of a treatment plan in which they utilized siblings to whom they taught a set of behavioral abilities to be used with their brothers or sisters who have ASD while playing. Results also revealed that all three dyads of children participants learned successfully from the experimentations. Dodd et al. (2008) utilized two behavior modification packages that include multiple-baseline-design-across-behaviors and multiple-baseline-design-across participants to change the social abilities of children diagnosed with Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS). The researchers used social stories in which the siblings of children diagnosed with PDD-NOS participated. Findings showed that unwanted behaviors such as giving excessive directions were reduced while making compliments significantly increased.

Many more investigations have been conducted to assess the effectiveness of sibling mediations. Most studies found similar results which were compiled in methodical reviews (Banda 2015; Shivers and Plavnick 2015). In a recent systematic review of the literature, Shivers and Plavnick (2015) reviewed 17 articles published between 1977 and 2012 in order to evaluate the helpfulness of sibling inclusion in the treatments of their brothers and sisters diagnosed with ASD. Overall, there were 72 children who had an intellectual disability, and their ages ranged from 3.58 to 12.08. The children who participated were diagnosed with ASD and Asperger disorder. Their siblings were 62 individuals, both males and females, and their ages ranged from 3.5 to 13. Shivers and Plavnick’s systematic review of the literature found that sibling interaction with children who have ASD or Asperger’s disorders led to positive results. Not only did children with ASD improve their social, play, communication, or functional skills, but their normally developing siblings also learned the skills of mediation.

Banda’s (2015) review of the literature of 15 published articles found similar results. The objective of the review was to replicate studies in which sibling mediation targeted children’s behaviors who were diagnosed with ASD and to assess the rigor of applied research design. The reviewed articles were published between 1977 and 2012. Overall, 38 children who were diagnosed with ASD participated in the reviewed studies. All participants had ASD excluding two children who had PDD-NOS and one who had PDD only. The average age of the participants was 6 years, and their ages ranged from three to 15. In addition to the 38 participating children with ASD or PDD, 36 of their normally growing siblings were also enrolled. The mean age for the siblings was 7 years with a range from three to 13. Alongside sibling participants, some peers of children diagnosed with ASD and adults, such as parents, teachers, or caregivers, also participated. The results of this review showed that when normally developing children are provided with adequate training, they can improve social- and communication-related behaviors of their brothers and sisters with ASD or PDD-NOS. Due to the inconsistencies across studies, Banda’s review addresses the empirical results rather vaguely with insufficient details to draw useful conclusions (Banda 2015). Further, both reviews utilized the same articles with a few differences. For example, Shivers and Plavnick (2015) used three articles (Coe et al. 1991; Pan 2011; Walton and Ingersoll 2012) that Banda (2015) did not include in his review. However, Banda included two articles which were not included in Shivers and Plavnick’s (2015) review repertoire (Dodd et al. 2008; Strain and Danko 1995). While both reviews used systematical review methodologies, none of them conducted a meta-analysis. Also, Shivers and Plavnick (2015) reviewed research that did not employ single-subject designs, that is, research that draws inferences based on individual effect size after studying a single subject. They predominantly focused on group-comparison design employing experimental and control groups to compute an effect size for groups of participants.

In light of the mentioned gaps, the purpose of this meta-analysis was to include articles that have been excluded by both reviewers as well as articles that have been published from 2015 to the present day. This meta-analysis also aims at excluding articles which do not meet the criteria of applied behavior analysis. Finally, this present meta-analysis focuses on the effectiveness of sibling-mediated interventions. To our knowledge, no meta-analyses on the effectiveness of sibling-mediated interventions have been conducted to this date. This meta-analysis intends to answer the following questions:

-

1.

What is the effectiveness of sibling-mediated interventions with brothers or sisters who have ASD?

-

2.

Are sibling-mediated interventions socially valid interventions?

-

3.

What are some methodological issues and strengths of the included studies?

Method

We conducted a search using EBSCO. The EBSCO databases included Psychological Abstracts, Social Sciences Index, and ERIC PsycInfo. We used the following key terms: sibling involvement, sibling-mediated instructional arrangement, peer-mediated interventions, sibling support, the inclusion of siblings, siblings as behavior modifiers, children promote social play with their siblings diagnosed with autism, help from siblings of children diagnosed with ASD, ASD and siblings, PDD-NOS and siblings, and family-mediated intervention. The studies that we selected met the following criteria: (a) researchers utilized typically developing siblings to prompt, model, teach, mediate, reinforce, and correct errors during social activities with children with ASD or PDD-NOS; (b) investigators utilized a single-subject design or group design; (c) studies focused on at least one child with ASD or PDD-NOS and a normally developing sibling; (d) studies addressed social play or skill instruction (making compliments or giving directions); (e) studies were published in a peer-reviewed journal; and (f) studies were available in English. We furthermore conducted an ancestral search for supplementary articles under the reference section of each selected study and found no additional studies. Overall, we selected a total of 16 studies that met our inclusion criteria. An independent faculty member re-examined 30% of the included articles in order to assess fidelity to the inclusion criteria. This examination resulted in a hundred percent agreement on the inclusion norms. We then analyzed the included articles on participant demographics, study settings, targeted skills, research design, intervention, and results. Table 1 provides a detailed summary of the studies with their effect sizes. We also addressed maintenance, generalization, and social validity.

Methods for Calculating Effect Size

We used the non-overlap of all pairs (NAP) method to calculate the overall effect size (Parker and Vannest 2009). NAP is an index of data overlap between conditions in single-subject design research. It has been confirmed and field tested with 200 published AB design contrasts. NAP is an innovative application for calculating effect sizes in single-subject design studies. Its various forms include area under the curve (AUC), the common language effect size (CL), the probability of superiority (PS), the dominance statistic (DS), Mann–Whitney U, and Sommers D. NAP’s main hypothetical benefit is that it is a comprehensive test of all possible sources of data overlap. All baselines are measured against all treatment data points. NAP is a probability score, generally ranging from 0.5 to 1 (Parker and Vannest 2009) that has been described as a strong methodology. It discriminates more effectively among results from a large number of published studies and accounts for human errors in calculations as opposed to the other three hand-calculated indices [i.e., percent of non-overlapping data points (PND), percent of non-overlapping data (PAND), and percent of data exceeding the median (PEM)]. It was also argued that a third advantage sought from NAP was its stronger validation through R2, which is perceived as the leading effect size in publications (Parker and Vannest 2009). We first calculated the NAP value between baseline and intervention conditions (AB) and then calculated the overall effect size and confidence interval. A faculty member independently calculated NAP for 30% of the selected studies and found 100% agreement with the NAP calculations.

Coding Procedures for Study Characteristics

We coded studies that met the inclusion criteria for participants’ characteristics, study designs, and types of graphs. Studies that met the criteria were labeled “Yes.” Otherwise, they were labeled “No” and were discarded. All authors reached a 100% agreement on the selection, inclusion criteria, and the coding system.

Coding Participants’ Characteristics

We coded articles for all participants, both target children’s and their brothers’ and sisters’ ages, genders, and diagnosis for the target population. Other important criteria that we coded was that participating children with autism must interact with their brothers or sisters and the latter population must prompt, model, teach, mediate, reinforce, and correct their errors. This criteria was coded 1 when the criterion was met. All 16 articles were rated 1.

Coding Design

For each study, the design used to demonstrate experimental control was recorded. These included multiple-baseline and reversal designs, parallel treatment, and ABAB design with withdrawal treatment. They all met our criteria and were labeled “Yes.”

Coding Procedures for Data Collection

AB design graphs provide the possibility for visually inspecting most single-case experimental designs. In most cases, multiple single-subject design graphs were found in each study. However, we only selected graphs that represented the performance of children with autism. Studies that reported such graphs were rated 1. Studies that did not report such graphs for participating children were rated 0 and were not taken into account in this meta-analysis. We calculated individual effect sizes for each child diagnosed with autism across behaviors and or across settings using the NAP method, then we calculated effect sizes for all children diagnosed with autism by study, and finally we calculated the overall effect size.

We used the NAP hand-calculation method to compare each baseline phase A data point with each intervention phase B data point. Firstly, we calculated the total possible pairs (total N). The total possible pair is the number of data points at baseline A times intervention phase B (NA × NB). Secondly, we counted all overlapping pairs by allotting one point to each overlap and half a point to a tie. Thirdly, we subtracted our overlapping pairs from the total possible pairs to obtain the non-overlap count which we finally divided by the total possible pairs to obtain the NAP effect size.

Results

Participants

Overall, 43 children diagnosed with either ASD, autism, PDD-NOS, or Asperger were enrolled. This sample size included 34 male and nine female participants whose ages ranged from 3 years to 15 years with an average of 6.09 years (SD = 2.76). Forty three normally developing siblings and peers also participated in the included studies of which there were both female and male children.

Settings

The 16 studies included in this meta-analysis were undertaken in various settings, including participants’ homes (Celiberti and Harris 1993; Coe et al. 1991; Colletti and Harris 1977; Dodd et al. 2008; Ferraioli and Harris 2011; Oppenheim-Leaf et al. 2012; Schreibman et al. 1983; Strain and Danko 1995, Tsao and Odom 2006; Walton and Ingersoll 2012), schools (Jones and Schwartz 2004; Rayner 2011a; Rayner 2011b), university settings (Baker 2000; Clark et al. 1989), and a preschool based in a university (Reagon et al. 2006).

Target Behaviors

Several behaviors such as social, living skills, language-related skills, and the diminution of unwanted behaviors were targeted. The former included socialization skills (Clark et al. 1989; Dodd et al. 2008; Strain and Danko 1995; Tsao and Odom 2006), plays, comments, interaction with peers (Celiberti and Harris 1993; Oppenheim-Leaf et al. 2012), joint attention (Ferraioli and Harris 2011), imitation abilities, matching, question answering and snack preparation (Rayner 2011a), and living skills or crafting such as tying a shoelace knot and bead stringing (Colletti and Harris 1977; Rayner 2011b). Other language-related skills were addressed by Jones and Schwartz (2004), and some ritualistic and excessive unwanted behaviors were also targeted to be reduced (Baker 2000; Clark et al. 1989).

Research Designs

Eleven of the 16 studies utilized multiple-baseline designs across individuals. Two studies used multiple-baseline designs across skills (Rayner 2011a; Reagon et al. 2006). In one study, parallel treatment was utilized (Jones and Schwartz 2004). Coletti and Harris (1977) used ABAB design in which siblings and their brothers worked on fine motor abilities. One study used withdrawal treatment (Strain and Danko 1995).

Interventions

Interventions were implemented as follows: (a) in some investigations, the researchers trained the siblings of children with ASD to run the intervention with their brothers and sisters, (b) the researchers used siblings of children with autism in video modeling to intervene, (c) the researchers used social stories, (d) the investigators trained caregivers to execute an intervention with target children and their brothers and sisters, and (e) the researchers trained children with autism to increase and improve their social interactions.

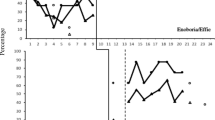

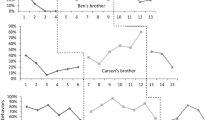

Studies in which researchers trained the siblings of children with autism to run the intervention with their brothers and sisters addressed social skills, bead stringing, and language-related skills. For example, Coe et al. (1991) assessed and taught children with autism how to utilize verbal and non-verbal play responses. The researchers used siblings as main trainers. Target behaviors encompassed functional manipulation and verbalization. The participating children with autism improved across conditions. Colletti and Harris (1977) trained a child participant how to prompt and how to reinforce his brother diagnosed with autism to string bead. The findings revealed effectiveness of interventions, and maintenances were also reported. In the same vein, another intervention assessed the effect of multiple children attending discussion sessions, peer monitoring, and group involvement in social activities on participating children diagnosed with autism. Findings revealed that children with autism also improved their social skills (Clark et al. 1989). In another research, the investigators taught normally developing children behavioral skills so as to assess their effects on their siblings with autism during play. Results showed that siblings with autism learned new skills and maintenance was also reported (Celiberti and Harris 1993). In Tsao and Odom (2006), the investigators also measured the sibling intervention approach with their ASD brothers and sisters in the areas of behaviors such as asking for assistance, asking questions, providing feedback, making eye contact, and proposing social plays. In this case, findings suggested that children with autism improved their social interactions significantly post-intervention with high maintenance. In order to address joint attention, Ferraioli and Harris (2011) trained developmentally normal children to implement joint attention related to behaviors such as providing responses and establishing eye contact with their brothers and sisters diagnosed with autism. Findings suggest that in general, children with autism have improved the targeted behavior, although not every child with autism improved in every area. In another study, typically growing children were instructed to utilize instruction, role play, and modeling with their brothers or sisters with autism. Results revealed an improvement of social interaction in children with autism (Oppenheim-Leaf et al. 2012). Social communication was also assessed. For example, Jones and Schwartz (2004) measured the effect of siblings and peers’ involvement to improve language-related abilities of children with autism. Overall, children with autism improved their communication skills through modeling. Finally, Walton and Ingersoll (2012) utilized sibling dyads to measure the effectiveness of sibling-implemented reciprocal imitation training. Results showed that three of the four children with autism displayed improvements in general imitation and all four showed improvement in joint commitment.

Several researchers used siblings of children with autism in video modeling (Reagon et al. 2006; Rayner 2011a; Rayner 2011b; Dodd et al. 2008). Raegon et al. (2006) presented a video modeling joint commitment to children with autism and their siblings. Findings suggest that the video modeling helped children with autism to improve their play skills. Similarly, Rayner (2011a) assessed the effect of adult and sibling models via video modeling to teach a child with autism how to imitate the targeted behaviors. Findings, however, showed that the child with autism failed to imitate the models. In another study, Rayner (2011b) examined the effect of video modeling on the ability of children with autism to tie shoelace knots. Little improvement was measured as well.

In one intervention, a researcher used social stories. Dodd et al. (2008) attempted to improve social skill and reduce excessive unwanted behaviors using social stories. Participating children were observed for change during play after attending to the stories. Results showed that only one participant actually improved his target behavior which was providing compliments to others.

In two studies, the investigators trained caregivers to execute interventions with children with ASD and their brothers and sisters (Schreibman et al. 1983; Strain and Danko 1995). Caregivers were employed to reinforce positive interactions between children with autism and their siblings (Strain and Danko 1995). Caregivers demonstrated mastery of the activities. Children with autism also improved their social interactions. In the other study (Schreibman et al. 1983), identification of money and communication behaviors were assessed. Video demonstration and discussions were utilized. Results showed that children with autism performed well on the tasks and generalization was noticed.

In one study, the investigators trained children with autism to increase and improve their social interactions (Baker 2000). Baker trained children with autism interaction skills. The children were prompted by adult participants. All three children with ASD showed improvement in the targeted behavior and a decrease in their thematic ritualistic behaviors.

Effect Size

We calculated an overall effect size for all 16 studies utilizing NAP methodologies and found 0.83 with a 95% CI [0.76, 0.90]. We split the data by mediation types, that is, siblings alone and siblings with peers and adult conditions. The effect size for studies in which siblings alone were used was 0.83 and 0.84 for studies in which siblings were employed alongside peers and adults, respectively. An independent samples t test was performed. There was not a significant difference in the scores for siblings alone (M = 0.83, SD = 0.13) and siblings, peers, and adult conditions (M = 0.84, SD = 0.11); F (14) = 0.42, p = 0.52. We also split the data by types of target behaviors, that is, play skills and social skills on the one side and academic knowledge and functional skills on the other side. Play and social skills included target behaviors such as play, play interaction, and play-related scripted comments, and academic and functional skills included targeted behaviors such as tying a shoelace knot, joint attention, responses, and making string beads. The effect size for studies which focused on play skills and social skills was 0.80, and the effect size for studies which focused on academic knowledge and functional skills was 0.87. An independent samples t test was performed. There was no statistical difference in the scores for play skills and social skills (M = 0.80, SD = 0.14) and academic knowledge and functional skills (M = 0.87, SD = 0.10); (F (14) = 1.07, p = 0.24). The presence of peers and or adults did not make any statistical difference in the results of sibling-mediated intervention. Also sibling-mediated intervention was evidenced to be the same across target behaviors. NAP results have been interpreted according to general guidelines. Parker and Vannest (2009) argued that tentative NAP values that range from 0 to 0.65 are weak effects, 0.66–0.92 are medium effects, and 0.93–1.0 l are large or strong effects. Transforming NAP to a zero chance level produces the following corresponding ranges: weak effects range between 0 and 0.31. Medium effects range between 0.32–0.84, and large or strong effects lay between 0.85–1.0. With regard to the guidelines, we interpreted the overall effect size of 0.83 as being a medium effect size for sibling-mediated intervention.

Maintenance and Generalization

Seven of 16 studies measured both maintenance and generalization (Baker 2000; Celiberti and Harris 1993; Ferraioli and Harris 2011; Oppenheim-Leaf et al. 2012; Reagon et al. 2006; Tsao and Odom 2006; Walton and Ingersoll 2012). For example, Walton discussed that imitation generalized to settings other than the ones in which children were trained and to other play equipments than the ones that children used initially. Maintenance alone was assessed in five studies (Clark et al. 1989; Colletti and Harris 1977; Dodd et al. 2008; Jones and Schwartz 2004; Coe et al. 1991). Coe et al. argued that learned play skills of children with autism were successfully maintained at a 30-day follow-up. Two studies assessed generalization alone (Rayner 2011b; Schreibman et al. 1983), and another two studies provided no information on maintenance and generalization (Rayner 2011a; Strain and Danko 1995).

Social Validity

Overall social validity was measured in 11 of the 16 studies. The investigators used multiple data collection methods of which were satisfaction surveys (Reagon et al. 2006), interview (Ferraioli and Harris 2011), semi-structured interview (Baker), blind observers (Walton), and naïve observers (Celiberti and Harris 1993). Reagon’s findings showed that one mother was absolutely happy with the intervention and sibling report indicated that they had fun interacting with their brothers with autism. In another study (Ferraioli and Harris 2011), brothers’ or sisters’ responses at the post-treatment revealed that they benefited from the intervention packages. They asserted that they learned mediating positive behaviors. Their parents also asserted that they were highly satisfied with the program. In Baker’s (2000) study, siblings argued that they liked to play with their brothers with autism only after the intervention, indicating that the program not only affected them, but that they also enjoyed it. Furthermore, the siblings reported that their brothers improved in some areas of play skills post-intervention compared with baseline. For example, regarding post-intervention effects on siblings, a sibling responded that her brother can play new games and ride bikes but he still has some limitations. Tsao and Odom (2006) also conducted a social validity assessment and found positive feedback although there were differences between participating children. In the study by Schreibman et al. (1983), parents reported a positive difference after the intervention. For example, prior to the intervention, siblings viewed their brothers and sisters with autism as weird and funny. But after the intervention, the siblings had a positive and an accepting view of their siblings with ASD.

Walton and Ingersoll (2012) used untrained blind observers to assess social validity. This assessment showed that children with autism and their brothers or sisters underwent noticeable changes after the interventions. Parents asserted that they believed the treatment caused their child with autism to improve his social engagement, play skill, and communication. Celiberti and Harris (1993) also used naïve observers to measure social validity. The latter believed that trained children can effectively mitigate undesired behaviors of their brothers or sisters with autism and help them improve their limited skills.

Discussion

This meta-analysis investigation aimed at examining the effects of sibling-mediated intervention on the functional skills, plays, communications, and social interaction skills of brothers or sisters with autism spectrum disorder. To our knowledge, the first intervention that enrolled siblings as mediators was conducted over 40 years ago. Several such studies have followed including systematic reviews, yet the present review is the first meta-analysis that statistically investigates the effect size of individual studies. Overall, the results of this present analysis showed that when normally developing siblings are trained, they can also train or enable their brothers or sisters who have autism to develop skills in diverse areas which include play skills and functional skills while decreasing unwanted behaviors. The results of this meta-analysis of sibling-mediated intervention are similar to results of a previous meta-analysis of peer-mediated intervention (Bene et al. 2014). A meta-analysis of peer-mediated instructional arrangement which included 13 studies about children diagnosed with autism found that typically developing peers can help other children who have autism to learn and improve their skills in areas of communication and behavior (Bene et al. 2014). Peer-mediated intervention was found to be robust as reflected in past research on peer intervention (Chan et al., 2009).

In addition to the reports on the gains of children with autism, data also suggest that most siblings acquired sufficient knowledge to implement the different interventions with their brothers or sisters with autism. This finding indicates that children of both genders can be trained as mediators to intervene with their brothers and sisters who have developmental disabilities. Regarding social validity, siblings reported that trainings have made a positive effect on their siblings with autism at post-intervention.

Limitations and Future Considerations

Despite the robust and positive indicators, some limitations were found across the reviewed studies. Regardless of the effectiveness of the interventions, many studies did not assess follow-up. Maintenance and generalization, when addressed, were measured within a short period of time. We believe that parents and researchers can motivate siblings to maintain similar levels of intervention effects following the interventions over longer periods of time in their respective homes. Unlike outside mediators, the benefit of using siblings is that siblings live with their brothers or sister with autism permanently.

Another limitation is the fact that the roles of individual siblings were not clearly defined in the intervention phases and that some siblings were passive mediators (Banda 2015). Some siblings were also taught the same skills alongside their brothers with autism. In this light, it was suggested that when possible investigators should pair appropriately siblings with the right type of intervention or right play setting. Further investigations that include more specific factors that relate to siblings are encouraged (Shivers and Plavnick 2015).

Regarding social validity, we believe that the methods used to collect data on parents’ and siblings’ perception of the effectiveness of the intervention methods are rather diverse. They included satisfaction surveys (Reagon et al. 2006), interviews (Ferraioli and Harris 2011), semi-structured interviews (Baker 2000), blind observers (Walton and Ingersoll 2012), and naïve observers (Celiberti and Harris 1993). Yet, we believe that the use of a validated Likert-like instrument which could provide total scores, means, and standard deviations is to be encouraged in following studies. In some studies, researchers relied on parents to collect data in their homes. Even though parents were trained to gather the data, we suggest that researchers consider systematic types of data collections in homes that include more rigorous reports. We also recommend that researchers include procedural integrity in their final report as most of the reviewed studies have no such reports.

References

Baker, M. J. (2000). Incorporating the thematic ritualistic behaviors of children with autism into games: increasing social play interactions with siblings. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2(2), 66–84.

Banda, D. R. (2015). Review of sibling interventions with children with autism. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 50(3), 303–315.

Bene, K., Banda, D. R., & Brown, D. (2014). A meta-analysis of peer-mediated instructional arrangements and autism. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1(2), 135–142.

Buggey, T. (2012). Effectiveness of video self-modeling to promote social initiations by 3-year-olds with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 27(2), 102–110.

Cardon, T. A. (2012). Teaching caregivers to implement video modeling imitation training via iPad for their children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(4), 1389–1400.

Celiberti, D. A., & Harris, S. L. (1993). Behavioral intervention for siblings of children with autism: a focus on skills to enhance play. Behavior Therapy, 24(4), 573–599.

Christensen, D. L., Braun, K. V. N., Baio, J., Bilder, D., Charles, J., Constantino, J. N., Fitzgerald, R. T., Daniels, J., Durkin, M. S., Kurzius-Spencer, M., Pettygrove, S., Lee, L. C., Robinson, C., Schulz, E., Wells, C., Wingate, M. S., & Zahorodny, W. (2018). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 65(13), 1.

Clark, M. L., Cunningham, L. J., & Cunningham, C. E. (1989). Improving the social behavior of siblings of autistic children using a group problem solving approach. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 11(1), 19–33.

Coe, D. A., Matson, J. L., Craigie, C. J., & Gossen, M. A. (1991). Play skills of autistic children: assessment and instruction. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 13(3), 13–40.

Colletti, G., & Harris, S. L. (1977). Behavior modification in the home: Siblings as behavior modifiers, parents as observers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 5(1), 21–30.

Dodd, S., Hupp, S. D., Jewell, J. D., & Krohn, E. (2008). Using parents and siblings during a social story intervention for two children diagnosed with PDD-NOS. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 20(3), 217–229.

Ferraioli, S. J., & Harris, S. L. (2011). Effective educational inclusion of students on the autism spectrum. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 41(1), 19–28.

Fombonne, E. (2018). The rising prevalence of autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(7), 717–720.

Green, J., Charman, T., McConachie, H., Aldred, C., Slonims, V., Howlin, P., Le Couteur, A., Leadbitter, K., Hudry, K., Byford, S., Barrett, B., Temple, K., Macdonald, W., & Pickles, A. (2010). Parent-mediated communication-focused treatment in children with autism (PACT): a randomized controlled trial. The Lancet, 375(9732), 2152–2160.

Jones, C. D., & Schwartz, I. S. (2004). Siblings, peers, and adults: differential effects of models for children with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 24(4), 187–198.

Krebs, M. L., McDaniel, D. M., & Neeley, R. A. (2010). The effects of peer training on the social interactions of children with autism spectrum disorders. Education, 131, 393–403.

McConachie, H., & Diggle, T. (2007). Parent implemented early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 13(1), 120–129.

Odom, S. L., Collet-Klingenberg, L., Rogers, S. J., & Hatton, D. D. (2010). Evidence-based practices in interventions for children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Preventing School Failure, 54, 275–282.

Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L., Leaf, J. B., Dozier, C., Sheldon, J. B., & Sherman, J. A. (2012). Teaching typically developing children to promote social play with their siblings with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 777–791.

Pan, C. Y. (2011). The efficacy of an aquatic program on physical fitness and aquatic skills in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 657–665.

Parker, R. I., & Vannest, K. (2009). An improved effect size for single-case research: nonoverlap of all pairs. Behavior Therapy, 40(4), 357–367.

Rayner, C. (2011a). Sibling and adult video modelling to teach a student with autism: imitation skills and intervention suitability. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 14(6), 331–338.

Rayner, C. (2011b). Teaching students with autism to tie a shoelace knot using video prompting and backward chaining. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 14(6), 339–347.

Reagon, K. A., Higbee, T. S., & Endicott, K. (2006). Teaching pretend play skills to a student with autism using video modeling with a sibling as model and play partner. Education and Treatment of Children, 517–528.

Schreibman, L., O’Neill, R. E., & Koegel, R. L. (1983). Behavioral training for siblings of autistic children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 16(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1983.16-129.

Shivers, C. M., & Plavnick, J. B. (2015). Sibling involvement in interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(3), 685–696.

Strain, P. S., & Danko, C. D. (1995). Caregivers’ encouragement of positive interaction between preschoolers with autism and their siblings. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 3(1), 2–12.

Tsao, L. L., & Odom, S. L. (2006). Sibling-mediated social interaction intervention for young children with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 26(2), 106–123.

Walton, K. M., & Ingersoll, B. R. (2012). Evaluation of a sibling-mediated imitation intervention for young children with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14(4), 241–253.

Whalon, K., & Hanline, M. F. (2008). Effects of a reciprocal questioning intervention on the question generation and responding of children with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 43, 367–387.

Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., Brock, M., Plavnick, J., Fleury, V., & Schultz, T. (2013). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: a comprehensive review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 1951–1966.

Xu, G., Strathearn, L., Liu, B., & Bao, W. (2018). Corrected prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among US children and adolescents. Jama, 319(5), 505–505.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bene, K., Lapina, A. A Meta-Analysis of Sibling-Mediated Intervention for Brothers and Sisters Who Have Autism Spectrum Disorder. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 8, 186–194 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00212-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00212-z