Abstract

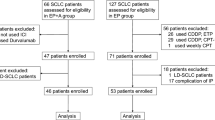

Survival beyond 2 years is rare in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) treated with chemotherapy alone. We describe a patient with ES-SCLC who was treated with carboplatin, etoposide and the programmed death-ligand 1 inhibitor atezolizumab in the IMpower133 study (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT02763579) and who achieved exceptionally long-term survival. Treatment-naïve patients with ES-SCLC (n = 403) were included in the IMpower133 study, and the identified patient had been randomised to the investigational treatment arm, where patients received induction therapy with carboplatin and etoposide plus atezolizumab for four 21–day cycles, followed by ongoing maintenance therapy with atezolizumab. The patient had achieved a partial response after induction therapy, and then received seven cycles of atezolizumab maintenance therapy until immune-related toxicities necessitated discontinuation. The patient was alive with an ongoing response and excellent performance status more than 6 years after starting treatment and 5 years after discontinuing atezolizumab maintenance. In conclusion, this patient with ES-SCLC from the IMpower133 study is a rare example of ongoing survival more than 6 years beyond diagnosis and the start of treatment with first-line atezolizumab. This demonstrates the potential durability of response with immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive cancer often diagnosed when the disease is extensive (ES-SCLC), with limited effective treatment options, and consequently survival rates of less than 1 year. |

We describe the remarkable case of long-term survival in a treatment-naïve patient with ES-SCLC who was enrolled in a clinical trial (IMpower133) and received first-line immunotherapy with the programmed death-ligand 1 inhibitor atezolizumab added to standard chemotherapy (carboplatin plus etoposide) followed by atezolizumab maintenance. |

What was learned from the study? |

During maintenance atezolizumab, the patient experienced immunotherapy-related toxicity that was managed by discontinuing treatment and using appropriate medications such as corticosteroids. |

Despite discontinuing atezolizumab after ~12 months of treatment, the patient has shown an ongoing partial response up to the most recent follow-up, more than 6 years after their diagnosis of ES-SCLC, without any further treatment. |

Introduction

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive neuroendocrine cancer with rapid onset, high metastatic potential and poor clinical outcomes [1, 2]. Almost all patients who develop SCLC have a history of heavy smoking, which leads to a genomically complex, heterogeneous cancer with a high somatic mutation rate [1]. Patients typically present with extensive-stage disease (ES-SCLC), which is not amenable to definitive radiotherapy due to extension beyond a tolerable radiotherapy port [1, 2].

For more than 3 decades, combination chemotherapy with platinum plus etoposide was the standard-of-care for the first-line treatment of ES-SCLC [1, 2]. Long-term survival of patients with ES-SCLC treated with such a regimen is rare, with a median overall survival (OS) of approximately 10 months and only approximately 5% of patients being alive at 2 years [1, 2]. However, the IMpower133 study with atezolizumab and the CASPIAN trial with durvalumab demonstrated a significant OS benefit with the addition of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)-targeted immune-checkpoint inhibitor to carboplatin and etoposide chemotherapy [3, 4]. Resultantly, the standard-of-care for patients with ES-SCLC changed to include concurrent atezolizumab or durvalumab with initial chemotherapy of platinum plus etoposide [5,6,7].

While PD-L1 inhibitors have undoubtedly improved survival for ES-SCLC patients, long-term survival (beyond 5 years) remains the exception rather than the rule [7]. Here, we describe a patient with ES-SCLC identified from the IMpower133 study who achieved exceptionally long survival following treatment with carboplatin, etoposide and atezolizumab.

Case

The 61-year-old man, prior to enrolment in IMpower133, had been admitted to our hospital with facial and neck oedema, cough and mild dyspnoea in September 2016. These symptoms had appeared 1 week previously. The patient was a heavy smoker with a 48 pack/year history. He also had a history of hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. The patient did not present with fever, weight loss or other symptoms. Physical examination of the patient revealed head, neck and upper extremity oedema and right-sided jugular distension. He had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) score of 1. Laboratory findings were within normal boundaries.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed multiple mediastinal and right hilar nodal conglomerates (Fig. 1A) and a pulmonary mass in the right upper lobe encasing the superior vena cava, with almost complete tumour thrombosis. The superior vena cava was markedly compressed in its middle third, with filiform passage of contrast observed on phlebography. An endovascular stent was inserted at this level to resolve the stenosis. Satellite nodules were also observed in the posterior sub-segment of the anterior right lobe.

Computed tomography images showing A mediastinal and right hilar adenopathy with multiple conglomerate masses involving the bronchus of the upper right lobe and surrounding the superior vena cava (27 October 2016), B partial response after induction therapy with four 21-day cycles of carboplatin + etoposide + atezolizumab (26 January 2017) and C continued partial response more than 5 years after stopping maintenance treatment (26 January 2023)

Bronchoscopy revealed direct signs of tumour invading into the anterior branch of the right upper lobe of the lung. A lung biopsy established a diagnosis of SCLC. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for CD56 and thyroid transcription factor-1, and negative for CD20 (Fig. 2A). The Ki-67 labelling index was 100% (Fig. 2B). Lymphocyte count was 2.1 × 109/L and neutrophil count was 4.3 × 109/L, giving a neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio of 2.05. PD-L1 expression levels were not evaluable. No assessment of tumour mutation burden was undertaken. A contrast-enhanced brain CT scan showed no metastases; however, bone metastases were detected on CT scan and with bone gammagraphy (Fig. 3).

After being diagnosed with ES-SCLC, the patient provided written informed consent and was enrolled in the IMpower133 study. He was randomised to carboplatin and etoposide plus atezolizumab induction therapy followed by atezolizumab maintenance (investigators were unaware of the patient’s treatment assignment until after unblinding). Starting on 2 November 2016, the patient received induction therapy with four 21-day cycles of intravenous (IV) carboplatin (area under the curve 5 mg/mL/min on day 1) and etoposide (100 mg/m2 on days 1–3). Atezolizumab (1200 mg IV) was administered on day 1 of each cycle. After the conclusion of the four induction therapy cycles, a partial response (PR) was confirmed (Fig. 1B). The patient then received six cycles of maintenance atezolizumab (1200 mg every 3 weeks) through May 2017, which were well tolerated, and a radiographic PR was maintained.

When the patient was evaluated prior to cycle 11, he reported dysarthria and somnolence over the previous week, and treatment was delayed. His physical examination, contrast-enhanced brain CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were all unremarkable, and his ECOG PS score was 1. His thyroid-stimulating hormone levels were elevated (45.6 µU/mL [normal range 0.4–4.0 µU/mL]), and the patient was diagnosed with acute hypothyroidism, which was successfully treated with levothyroxine.

Atezolizumab maintenance treatment (cycle 11) was resumed in July 2017, but 5 days after treatment the patient was admitted to the emergency room with fever of > 38 °C. Laboratory evaluation revealed grade 4 renal dysfunction, and a kidney biopsy was consistent with immunotherapy-induced nephropathy (Fig. 4), which was treated with methylprednisolone (250 mg/day for 3 days) followed by prednisone (60 mg/day tapered over 4 weeks). Atezolizumab was discontinued due to this immune-mediated adverse event. However, with ongoing disease control, no further therapy was considered to be indicated, and he was observed radiographically.

At the most recent follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic with an ECOG PS score of 0. A repeat chest CT scan in January 2023 showed an ongoing PR (Fig. 1C), more than 6 years after diagnosis.

IMpower133 was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Protocol approval was obtained from an independent ethics committee at each site. All patients provided written informed consent. The patient presented in this case report provided written informed consent to participate in the IMpower133 study and consent for publication of their anonymised details was obtained on 23 June 2022.

Discussion

The addition of immunotherapy to platinum plus etoposide chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for ES-SCLC represents a major breakthrough for this exceptionally lethal disease, resulting in a ~10% increase in progression-free survival and OS compared with standard treatment [8]. This case illustrates the degree of benefit that can be achieved with this approach, where the patient received atezolizumab for ~12 months and PR was maintained for more than 6 years, with manageable toxicity.

Long-term survival rates have been reported with PD-L1 inhibitors in clinical trials; the 18-month OS rate in the atezolizumab arm of the IMpower133 study was 34.0% [9], and the 5-year exploratory OS rate from a merged analysis of IMpower133 and the single-arm IMbrella A extension study was 12% [10]. Further, the 36-month survival rate with durvalumab in the CASPIAN study was 17.6% [11]. Although in these studies patients continued PD-L1 inhibitor treatment until disease progression, the patient reported here, who was enrolled in IMpower133, discontinued atezolizumab due to toxicity but maintained his initial response without progression.

Ours is not the first case report of a patient with ES-SCLC achieving long-term survival gains after immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy. Zhang and colleagues reported a patient with ES-SCLC who survived for 50 months after treatment with sequential ICIs, including toripalimab, tislelizumab and durvalumab [12]. However, unlike our patient, this patient was continuously treated during periods of disease stability until progression. Konishi and colleagues reported a patient who received atezolizumab (along with etoposide plus platinum) for 6 months and was still alive 35 months later [13]. However, that patient received radiotherapy for chylothorax, followed by chemotherapy with nogitecan and then amrubicin after progression [13], whereas our patient received no further treatment after discontinuation of atezolizumab. Although the optimal duration of maintenance therapy with atezolizumab is not known, it is possible that our patient belongs to a subgroup of individuals in whom several months of such treatment results in sustained disease control. Further research is needed to identify biomarkers (or other factors) that may help characterise and define the subgroup of patients who can safely discontinue atezolizumab, and to determine the optimal duration of atezolizumab maintenance therapy.

Of potential prognostic importance is the patient’s early tumour response, since early tumour shrinkage/response is associated with improved survival in patients with ES-SCLC [14,15,16], although our patient also had a number of characteristics that could have contributed to his long-term survival, including age < 65 years [17, 18] and good performance status [16, 19,20,21,22,23]. Further, his neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (2.05) was consistent with that considered to be prognostic for better survival (a ratio of ≤ 3.43), as reported in a study that investigated the prognostic role of inflammatory markers in patients with ES-SCLC who were treated with atezolizumab plus chemotherapy [24]. However, our patient also had risk factors for reduced survival, including male gender [16] and bone metastasis [17, 18].

Another potential indicator of prolonged survival in our patient was the development of immune-related adverse events, specifically immune-mediated hypothyroidism and nephropathy. It is possible that these treatment-related toxicities were connected to the patient’s exceptionally durable response to treatment since the development of such adverse events during immunotherapy is associated with improved survival in a range of cancer types, including lung cancer [25,26,27]. A pooled analysis of three phase III trials (IMpower130, IMpower132 and IMpower150) showed significantly prolonged survival in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who did versus did not develop immune-related adverse events with atezolizumab [28]. Further, immune-mediated thyroid dysfunction, which our patient developed, was associated with improved long-term survival in an analysis of patients with NSCLC receiving immunotherapy [29]. However, the relationship between survival and immune-related adverse events is less clear-cut in patients with SCLC. D’Aiello and colleagues found no relationship between immune-mediated thyroid dysfunction and survival in a mixed cohort of SCLC and NSCLC patients who were receiving immunotherapy [30], and two multicentre retrospective studies in SCLC patients, one conducted in Germany [31] and the other in the USA [27], reported conflicting results. The USA study found that immune-mediated adverse events were associated with significantly longer survival [27], whereas no such association was found in the German study [31]. Further data in larger patient cohorts are needed to clarify the relationship between immune-mediated adverse events and survival in patients with SCLC.

The limitation of this report is that inherent to all case reports, i.e., it is difficult to make generalisations or draw firm conclusions from observations of a single patient. In addition, next-generation sequencing was not undertaken, so genomic information potentially relevant to his survival status was not collected. Further, there is a possibility that the persisting changes we observed on CT were indicative of inflammation rather than persisting tumour; however, we were not able to confirm this. The strengths of our report include the good availability of clinical, laboratory and imaging data for the patient because the patient had participated in a clinical trial where regular and thorough assessments were made during trial visits.

Conclusions

Long-term outcomes observed for this patient with ES-SCLC, treated in the first-line setting with atezolizumab, demonstrate the potential durability of response with immunotherapy, even after treatment discontinuation. Individual patients may experience outcomes to novel treatment strategies that are significantly outside those typically reported in clinical trials.

Data Availability

Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient-level data through the clinical study data request platform: https://vivli.org. Further details on Roche’s criteria for eligible studies are available here: https://vivli.org/members/ourmembers/. For further details on Roche’s Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here: https://www.roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing.htm.

References

Bernhardt EB, Jalal SI. Small cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2016;170:301–22.

Farago AF, Keane FK. Current standards for clinical management of small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7:69–79.

Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, et al. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2220–9.

Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394:1929–39.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in oncology: small cell lung cancer. Version 2.2022. 2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#site. Accessed 10 Feb 2022.

Pacheco J, Bunn PA. Advancements in small-cell lung cancer: the changing landscape following IMpower-133. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20(148–60): e2.

Plaja A, Moran T, Carcereny E, et al. Small-cell lung cancer long-term survivor patients: how to find a needle in a haystack? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:13508.

Facchinetti F, Di Maio M, Tiseo M. Adding PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of extensive stage small cell lung cancer (SCLC): a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:2645.

Liu SV, Reck M, Mansfield AS, et al. Updated overall survival and PD-L1 subgroup analysis of patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer treated with atezolizumab, carboplatin, and etoposide (IMpower133). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:619–30.

Liu SV, Dziadziuszko R, Sugawara S, et al. Five-year survival in patients with ES-SCLC treated with atezolizumab in IMpower133: imbrella a extension study results [abstract OA01.04]. Presented at: IASCL 2023 World Conference on Lung Cancer. 2024. https://www.jto.org/article/S1556-0864(23)00827-4/fulltext. Accessed 10 Jan 2024.

Paz-Ares L, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, et al. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: 3-year overall survival update from CASPIAN. ESMO Open. 2022;7: 100408.

Zhang X, Zheng J, Niu Y, et al. Long-term survival in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer treated with different immune checkpoint inhibitors in multiple-line therapies: a case report and literature review. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1059331.

Konishi K, Kuwahara H, Morita D, Imai S, Nagata K. Prolonged survival in a patient with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer in spite of discontinued immunotherapy with atezolizumab. Cureus. 2023;15: e37757.

Hagmann R, Zippelius A, Rothschild SI. Validation of pretreatment prognostic factors and prognostic staging systems for small cell lung cancer in a real-world data set. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:2625.

Ishida M, Morimoto K, Yamada T, et al. Early tumor shrinkage as a predictor of favorable treatment outcomes in patients with extensive-stage SCLC who received programmed cell death-ligand 1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy: a prospective observational study. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2023;4: 100493.

Ma X, Zhang Z, Chen X, et al. Prognostic factor analysis of patients with small cell lung cancer: real-world data from 988 patients. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12:1841–50.

Huang LL, Hu XS, Wang Y, et al. Survival and pretreatment prognostic factors for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: a comprehensive analysis of 358 patients. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12:1943–51.

Zou J, Guo S, Xiong MT, et al. Ageing as key factor for distant metastasis patterns and prognosis in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. J Cancer. 2021;12:1575–82.

Jones GS, Khakwani A, Pascoe A, et al. Factors associated with survival in small cell lung cancer: an analysis of real-world national audit, chemotherapy and radiotherapy data. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:4055–68.

Longo V, Pizzutilo P, Catino A, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: an Italian real-world retrospective analysis of 244 patients treated over the last decade. Thorac Cancer. 2022;13:3486–95.

Morimoto K, Yamada T, Takeda T, et al. Efficacy and safety of programmed death-ligand 1 inhibitor plus platinum-etoposide chemotherapy in patients with extensive-stage SCLC: a prospective observational study. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022;3: 100353.

Moser SS, Bar J, Kan I, et al. Real world analysis of small cell lung cancer patients: prognostic factors and treatment outcomes. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:317–31.

Sagie S, Maixner N, Stemmer A, Lobachov A, Bar J, Urban D. Real-world evidence for immunotherapy in the first line setting in small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2022;172:136–41.

Kutlu Y, Aydin SG, Bilici A, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic markers in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer treated with atezolizumab in combination with chemotherapy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102: e33432.

Brown LJ, da Silva IP, Moujaber T, et al. Five-year survival and clinical correlates among patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma and renal cell carcinoma treated with immune check-point inhibitors in Australian tertiary oncology centres. Cancer Med. 2023;12:6788–801.

Guezour N, Soussi G, Brosseau S, et al. Grade 3–4 immune-related adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients are correlated with better outcome: a real-life observational study. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:3878.

Ricciuti B, Naqash AR, Naidoo J, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and clinical outcomes to programmed cell death protein 1/programmed death-ligand 1 blockade in SCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2020;1: 100074.

Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, et al. Association of immune-related adverse events with efficacy of atezolizumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: pooled analyses of the phase 3 IMpower130, IMpower132, and IMpower150 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9:527–35.

Li Z, Xia Y, Xia M, et al. Immune-related thyroid dysfunction is associated with improved long-term prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with immunotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2023;15:690–700.

D’Aiello A, Lin J, Gucalp R, et al. Thyroid dysfunction in lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs): outcomes in a multiethnic urban cohort. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:1464.

Stratmann JA, Timalsina R, Atmaca A, et al. Clinical predictors of survival in patients with relapsed/refractory small-cell lung cancer treated with checkpoint inhibitors: a German multicentric real-world analysis. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2022;14:17588359221097191.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

We would like to thank Lourdes Gómez from the Pathology Unit of the Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío for helping with diagnosis and providing the images used in this case report. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Jo Dalton, who wrote the outline and first draft of the manuscript, on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications; Tracy Harrison of Springer Healthcare Communications, who provided additional editorial assistance prior to submission; and Catherine Rees, who provided assistance with post-submission revisions on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications. Support for this assistance was funded by Roche.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article and take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Funding

The IMpower133 study was sponsored by Roche, who contributed to that study’s design, data analysis and data interpretation in collaboration with the authors of that study. The funders had no role in the collection of data reported in this case report. Sponsorship for editorial assistance for this article and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee for publication of this article were funded by Roche.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Reyes Bernabé; Patient care: Reyes Bernabé; Formal analysis and investigation: Reyes Bernabé, Stephen V. Liu, Amparo Sánchez-Gastaldo and Miriam Alonso García; Writing-original draft preparation: Reyes Bernabé and Stephen V. Liu; Writing- review and editing: Reyes Bernabé, Stephen V. Liu, Amparo Sánchez-Gastaldo and Miriam Alonso García. All authors have read and approve the final manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Stephen V. Liu has been on an advisory board for or acted as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Blueprint, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Catalyst, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Elevation Oncology, Genentech/Roche, Gilead, Guardant Health, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck/MSD, Merus, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Takeda and Turning Point Therapeutics and has received research funding (to institution) from Alkermes, Elevation Oncology, Genentech, Gilead, Merck, Nuvalent, RAPT and Turning Point Therapeutics. Reyes Bernabé, Amparo Sánchez-Gastaldo and Miriam Alonso García declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

IMpower133 was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Protocol approval was obtained from an independent ethics committee at each site. All patients provided written informed consent. The patient presented in this case report provided written informed consent to participate in the IMpower133 study. Consent for publication of their anonymized details was obtained on 23 June 2022.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bernabé, R., Liu, S.V., Sánchez-Gastaldo, A. et al. Long-Term Survival and Stable Disease in a Patient with Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer after Treatment with Carboplatin, Etoposide and Atezolizumab. Oncol Ther 12, 175–182 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-023-00257-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-023-00257-0