Abstract

Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a subtype of lung cancer, the second most common cancer diagnosis worldwide. Currently, there is little published qualitative research that provides insight into the disease-related symptoms and impacts that are relevant to patients living with SCLC as directly reported by patients themselves.

Methods

This qualitative, cross-sectional, noninterventional, descriptive study included concept elicitation interviews with participants diagnosed with SCLC and the development of a conceptual model of clinical treatment benefit.

Results

Concept elicitation interview data from 26 participants with SCLC were used to develop a conceptual model of clinical treatment benefit that organized 28 patient-reported concepts into two domains: disease-related symptoms (organ-specific and systemic) and impacts. Organ-specific symptoms included cough, chest pain, and difficulty breathing. Systemic symptoms included pain, fatigue, appetite loss, and dizziness. Impacts included physical functioning, role functioning, reduced movement, impact on sleep, and weight loss.

Conclusion

As evidenced by this study, people with SCLC experience considerable and significant symptoms and impacts, including physical and role functioning challenges, that affect their quality of life. This conceptual model will inform the design of a patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaire for a future SCLC clinical trial, helping to establish the content validity of the items and questionnaires used in the trial and ensuring that the questionnaires and items selected are appropriately targeted to the population. This conceptual model could also be used to inform future SCLC clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is a paucity of published qualitative research that provides insight into how patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) feel and function, leaving a gap in the knowledge required to carry out patient-centered drug development in SCLC. |

In this study, concept elicitation interviews with 26 participants diagnosed with SCLC were conducted to create a conceptual model of clinical treatment benefit in SCLC that includes 28 unique concepts. |

Participants reported experiencing core disease-related symptoms of cough, chest pain, difficulty breathing, pain, and fatigue, as well as physical and role functioning challenges that affect their quality of life. |

The conceptual model developed for this study can be used to inform the selection of relevant patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires and items in future SCLC clinical trials, supporting the content validity of the items and questionnaires used in such trials. |

Introduction

Globally, lung cancer is the second most common cancer diagnosis, with an estimated 2.2 million incident cases in 2020 alone [1]. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [2] and is mainly divided into two subgroups based on histological findings: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). SCLC is strongly correlated with smoking, with more than 90% of cases occurring in people who are current or former smokers [3]. The symptoms of SCLC and NSCLC are similar, but SCLC is differentiated from NSCLC by its quick doubling time and early development of metastases [4].

Patients with SCLC are typically symptomatic at the time of diagnosis, due to the extensive and rapid growth of tumors, and often present with fatigue, neurological issues, bone pain, difficulty breathing, cough, and severe weight loss [3, 5]. SCLC is an aggressive cancer with a poor prognosis; data from the USA demonstrates a 2-year survival rate of just 8% in patients with extensive-stage disease [6]. Furthermore, fewer than 2% of patients survive longer than 5 years post-diagnosis [7]. Current treatment modalities for SCLC include radiotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and platinum-based chemotherapy with etoposide [8]. However, management of the disease is complicated, as it often becomes resistant to first-line systemic therapies and disease remission can be short-lived [6]. Although treatment is essential to prolonging survival for those diagnosed with SCLC, there can be significant short- and long-term effects on patient quality of life, with treatment toxicity surpassing potential benefit [3].

Robust clinical evidence that examines the clinical aspects of SCLC exists [4, 5, 8, 9]; however, patients’ needs, values, and preferences are often neglected, even though these perspectives are central to patient-centered drug development and treatment assessment [10]. Indeed, regulatory agencies, such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), urge the use of qualitative patient experience data. Specifically, the FDA recommends concept elicitation interviews, which use open-ended questions to spontaneously elicit concepts important to patients, to inform patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurement strategies and establish the content validity of PRO questionnaires used in clinical trials [11,12,13]. In oncology clinical trials, the FDA also recommends collecting PRO data on disease-related symptoms, and physical and role functioning impacts that are specific to the context of use [14]. Collecting qualitative patient experience data on these topics can in turn improve the relevance and appropriateness of the PRO questionnaires used in clinical trials for patients with SCLC.

The value of patient experience extends beyond regulatory requirements: understanding how patients feel and function can increase access to resources and improve health outcomes [15]. To wit, measuring the patient’s disease and treatment experience is essential for both adhering to regulatory recommendations and ensuring patients’ needs are met [16]. A range of PRO questionnaires that have undergone validation are currently used in clinical lung cancer research for both SCLC and NSCLC, including the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire core and lung cancer modules (EORTC QLQ-C30, QLQ-LC13, and QLQ-LC29), the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General and Lung cancer modules (FACT-G and FACT-L), the Lung Cancer Symptom Scale (LCSS), and the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) [17]. However, these questionnaires were not developed specifically for SCLC. As such, many of these questionnaires capture broad concepts, such as general quality of life, or symptoms that are not directly related to SCLC. Furthermore, none of these questionnaires fulfill the regulatory evidentiary expectations of the FDA’s drug development tool qualification program.

There is currently a paucity of qualitative literature that provides insight into the symptoms, as well as physical and role functioning impacts on daily living that matter to patients living with SCLC. Many existing qualitative studies group patients living with SCLC with other lung cancer populations, potentially obscuring any unique challenges the SCLC patients may experience [18,19,20]. Qualitative research with SCLC patients is needed to understand whether preexisting PRO questionnaires historically used in lung cancer research sufficiently and comprehensively measure the SCLC disease-related symptoms and physical and role functioning impacts that matter to SCLC patients.

Few studies have conducted concept elicitation interviews with patients with SCLC regarding their experience with the disease. A notable exception is the research conducted by the Small Cell Lung Cancer Working Group, as part of the PRO Consortium of the Critical Path Institute. At the time of this writing, the researchers have undertaken concept elicitation interviews with patients living with SCLC to develop an SCLC symptom measure, informed by the Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Symptom Assessment Questionnaire (NSCLC-SAQ, qualified by the FDA in 2018) [21], which will be modified to fit the SCLC context of use. However, the proposed conceptual framework for the instrument includes only symptoms and symptom severity and does not explicitly include impacts on physical or role functioning [22], which are both critical factors when measuring patient quality of life [23].

Aiming to address the lack of robust qualitative data in this patient population, this study used concept elicitation interviews with patients living with SCLC to identify disease-related symptoms, and the impacts of the disease on physical and role functioning. Thus, this research addresses an important gap in the literature, not only providing patients’ lived experiences regarding disease-related symptoms but also regarding how patients living with SCLC function. Moreover, the conceptual model was developed with a specific focus on clinical treatment benefit, not the broader patient experience, and can therefore be used as a foundation for the selection or development of appropriate PRO questionnaires in future SCLC clinical trials.

Methods

This qualitative, cross-sectional, noninterventional, descriptive study included concept elicitation interviews with participants diagnosed with SCLC, analysis, and conceptual model development.

Study documents, including the protocol, demographic and health information form, interview guide, screener, and informed consent form received institutional review board (IRB) ethical approval from WCG IRB (IRB 20212620). This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. All participants provided written consent before proceeding with the interviews.

Concept Elicitation Interviews with SCLC Patients

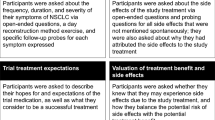

Concept elicitation was conducted to gather data on the lived experiences of SCLC in patients’ own words [24]. A 1:1 interviewing approach was used with a semi-structured interview guide designed to elicit information on SCLC symptoms and the impacts of living with SCLC, including physical functioning and role functioning. Targeted probes were used to obtain clarification or additional information on concepts spontaneously reported, and specific prompts were used to investigate concepts of interest that were not spontaneously mentioned. Probes were only used to follow-up after patients had the initial opportunity to report on symptoms and impacts of SCLC spontaneously in response to initial open-ended questions.

Participants

Interview participants in the USA were identified through two independent agencies that recruit through a wide geographical range of patient networks. Inclusion criteria were as follows: 18 years old or older, a confirmed diagnosis of SCLC, has received first-line treatment, willing and able to participate in one audio-recorded interview lasting 60–90 min, English-speaking, and able to provide informed consent for the interview. Participants diagnosed with any other cancers were excluded.

Purposive nonprobability sampling was used to guide the recruitment of SCLC patients [25]. The research team recruited participants until conceptual saturation was achieved, i.e., the point at which no new concepts emerge in interviews [26]. The aim was to recruit patients whose disease had failed platinum-based chemotherapy and who had received second-line treatment. However, due to the rarity of SCLC, and the likelihood of near-term patient death following the failure of first-line treatment, recruitment was open to any patient diagnosed with SCLC who had initiated first-line treatment.

Interview Conduct

Study personnel conducted telephone or online interviews between July and September 2021. Interviews lasted 60–90 min. Demographic and health information data were collected from participants via REDCap [27, 28]. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized.

Analysis

Interview transcripts were inductively coded and analyzed conceptually and thematically [29] using ATLAS.ti software [30, 31]. Two researchers independently coded the first transcript, compared codes, and came to agreement on the first version of the codebook. Three researchers were trained on the codebook and coded separate transcripts. Weekly meetings were held to review the application of codes across transcripts, compare codes for overlaps and inconsistencies, ensure coding consensus, synthesize codes, and update the codebook with newly identified concepts.

Conceptual analysis was focused on specifying symptom and impact concepts. Thematic analysis was focused on understanding the broader patient experience in terms of the connection between different symptoms and impacts.

Conceptual saturation was assessed by ordering interviews chronologically, then grouping interviews into one group of six transcripts and an additional four groups of five transcripts each. Concepts emerging in each group were compared sequentially to assess whether saturation had been reached (i.e., no new concepts emerged) [29, 31, 32].

Conceptual Model Development

Concepts identified via qualitative analysis were arranged based on FDA draft guidance around core outcomes to be assessed in cancer clinical trials [14]: disease-related symptoms, and physical and role functioning impacts. Additional impact categories were created as needed, based on data from interviews. Concepts were excluded if they did not relate to clinical treatment benefit or the PRO categories documented in the FDA guidance (e.g., social functioning, patient/provider communication), as the objective of the study was to create a conceptual model that could be used to directly inform PRO measurement strategies in SCLC clinical trials. While the FDA recommends collecting symptomatic adverse events (AEs) specific to treatment via PRO questionnaires in oncology clinical trials, we excluded concepts specific to symptomatic AEs from the model, since our participant sample had a wide variety of treatments and treatment experiences.

Results

Results include participant characteristics, key concepts identified by patients, the conceptual model of clinical treatments benefit that reflects the key concepts identified by patients, and key themes that emerged from analyzing how patients discussed the relationship between concepts.

Participant Characteristics

Twenty-six patients living with SCLC participated in this study. Participants were predominantly female (n = 19; 73.1%), with a mean age of 61 years. Four patients (15.4%) were Black/African American and 3 (11.5%) were Hispanic/Latino (Table 1). Eleven patients (42.3%) had limited-stage disease, meaning that the cancer is confined to the ipsilateral hemithorax and radiation is a therapeutic option [4]. Nine patients (34.6%) had extensive-stage SCLC, defined as cancer spreading to the other lung or parts of the body [4]. Disease stage data was missing for six patients (23.1%) (Table 2).

Key Concepts Identified by Patients

Coding of patient interview transcripts resulted in 280 codes. After codes irrelevant to treatment benefit were excluded and repetitive concepts were synthesized, 18 unique concepts related to disease-related symptoms and 10 concepts related to impacts were identified. Conceptual saturation was achieved in Group 3, i.e., no additional concepts emerged in Groups 4 and 5.

Below is a description of the two major domains: disease-related symptoms (organ-related and systemic) and impacts (physical functioning, role functioning, sleep, and weight loss). Organ-specific symptoms include cough (coughing up blood, phlegm, and hoarseness), chest/arm/shoulder pain (chest pain and arm/shoulder pain), and difficulty breathing (difficulty breathing in general, difficulty breathing at rest, difficulty breathing upon exertion, and wheezing). Systemic symptoms include pain, fatigue (tiredness, feelings weak, needing to sit/lie down, lack of energy, and thinking clearly/concentration problems due to mental tiredness), appetite loss, and dizziness. Impacts include physical functioning [daily activities (symptoms limiting daily activities), underlying factors limiting physical functioning (reduced endurance, reduced strength, and reduced balance), and impacts on movement (reduced bending over, reduced squatting, and reduced walking)], role functioning (stopping or limiting work or hobbies), difficulty sleeping, and weight loss. All concepts are illustrated in the conceptual model of clinical treatment benefit (Fig. 1); a table of exemplary quotes for each concept within the conceptual model is available in the supplementary materials (Supplementary materials S1 Table 3).

Symptoms

Organ-Specific Symptoms

Organ-specific symptoms were localized to the lungs; they included cough, chest/arm/shoulder pain, and difficulty breathing. Organ-specific symptoms could be triggered by certain situations or activities (e.g., climbing stairs, poor air conditions, etc.) or arise spontaneously.

Many participants differentiated between dry coughs [“(It’s) an annoying dry cough, kind of scratchy, a tickly kind of feeling from inside… it’s not painful, but it’s just bothersome” (US010)] and coughs that produce blood or phlegm. Some participants reported hoarseness as an aspect of coughing.

Participants described chest/arm/shoulder pain as sharpness, tightness, a burning sensation, or pressure in the chest, arm, and/or shoulder area, and indicated that it is typically more intense than an ache [“(Chest pain) was like a pushing on my chest” (US011)]. Participants described difficulty breathing as getting less air, shallow breathing, and/or not getting a complete breath [“I feel like I'm being suffocated… like if you put a pillow over someone’s face” (US003)].

Many participants differentiated between difficulty breathing in general, difficulty breathing that was triggered by exertion, and difficulty breathing that seemed to arise spontaneously while at rest. Some participants reported wheezing as an aspect of difficulty breathing.

Systemic Symptoms

Systemic symptoms, defined as those affecting the entire body, were described by patients and included pain, fatigue, appetite loss, and dizziness. Pain was described as a physical pressure or an achy feeling that could occur anywhere in the body [“My knees and my legs, like walking down the steps, it’s painful” (SD-03)].

Participants described fatigue as tiredness, feeling weak, needing to sit or lie down, lacking energy, and/or mental tiredness that limited clear thinking and concentration.

“I just tire easy. I run out of energy quickly and have to sit, don’t feel like walking around or being a little active. Just kind of a draining feeling, just low energy. It’s one of those things where you’ll sit down and then if you want to get back up again, you really don’t want to get back up. It’s just like you're just sitting there shrinking.” (US010).

“It’s like I’m not quite thinking that clearly and I can’t concentrate… I know I really have to have a nap.” (USA 2).

Many participants reported that they relied on naps throughout the day to regain their energy levels; however, for some, fatigue was described as unavoidable, regardless of how much sleep they got [“It feels like no matter how much I sleep; I still wake up and I’m tired… It’s just feeling constantly tired no matter what” (US005)].

Most participants reported appetite loss with SCLC [“I don’t eat anywhere near like I ate before” (US010)]; however, it was unclear when this was a treatment-related symptom or a symptom of the disease itself. Individuals noted that certain foods they previously enjoyed now taste bad. Some forgot to eat meals and their eating schedule was altered by frequently eating smaller meals or snacks throughout the day rather than larger meals. Participants also described lacking appetite during certain times of the day (e.g., morning or night).

Many participants described dizziness as lightheadedness in its milder form and some described it as vertigo in its more severe form [“It’ll feel like vertigo… it’ll just come over me like a whirlwind” (SD-03)]. Participants stated dizziness could be triggered by physical activity or carrying heavy objects; dizziness also caused balance issues and was linked to a reduced ability to bend over.

Impacts

Physical Functioning

Participants reported many physical functioning challenges, including how symptoms limit daily activities, the underlying factors that limit physical functioning, and impacts on movement.

Physical Functioning: Symptoms Limiting Daily Activities

All participants reported that their symptoms limited their daily activities. Examples of daily activities impacted included cooking, cleaning, running errands, driving, taking care of personal hygiene, traveling long distances, and doing physical activity (e.g., exercising). Some participants reported minor impacts (e.g., reducing vigorous exercise) and some reported very severe impacts (e.g., too tired to get out of bed). Many participants reported that were able to take care of basic daily activities but that they had to change the type of activities they were doing, limit the amount of time they spent on daily activities, and/or pace or break down their daily activities to make them achievable.

“Heavy cleaning I don’t do. And I don’t cook big meals… I’ll cook little things.” (US005)

“I used to… go in the garden, pick the veggies, and then I’m canning all day long… I can’t do that anymore. Now I have to do it within an hour or two, and then that’s it for the day.” (USA5)

Physical Functioning: Underlying Factors Limiting Physical Functioning

Participants reported reduced endurance, strength, and balance as underlying factors that limit physical functioning across all activities. All participants discussed reduced endurance as difficulty doing activities for as long as one used to before the SCLC diagnosis (“I don’t have the stamina that I used to ” [SD-02])and/or at the pace that one used to [“I feel exertion if I try to walk faster” (US003)].

Most participants reported reduced strength, particularly in the arms [“My physical strength is gone. I used to be able to lift pretty heavy stuff, and now, it’s like, lifting a hairbrush… I’m so tired that it’s… difficult.” (US014)]. Some participants linked reduced strength to muscle wasting [“I feel like I have lost all muscle mass… I definitely feel weak” (SD-03)].

Reduced balance was also discussed by some participants [“I feel like I'm leaning to one side or something sometimes when I'm walking” (US008)]. When balance issues are severe, participants reported that they feel like they are going to fall [“My balance is extremely off, so I find, even when coming into the house, I’ll hand my purse to my husband, because I don’t want to have the purse on my one side… I don’t want to fall” (SD-04)]. Furthermore, participants explained that reduced balance could arise spontaneously, be caused by exerting oneself, or be caused by dizziness.

Physical Functioning: Impacts on Movement

Impacts on movement, including reduced ability to bend over, reduced ability to squat, and reduced ability to walk were highlighted by participants. Some participants reported bending over was either challenging due to it causing dizziness or being physically impossible [“I can’t bend down and pull weeds. I have to go on my knees and pull weeds, which is not what I am used to doing. So, bending down is an issue. And that then impacts all kinds of things, certainly in the garden” (USA5)].

A few participants discussed reduced ability to squat as a major underlying factor that limited their ability to do activities, particularly house or yard work [“To grab dishes out of the dishwasher, if I keep on doing the bending and standing motion (that’s hard)” (SD-01)]. Participants further explained that reduced ability to squat limits picking up items such as groceries, and the combination of squatting and picking up items may result in balance issues.

Most participants described reduced walking due to a range of symptoms (including coughing, difficulty breathing, pain, and fatigue) and other impacts (including weight loss, reduced strength, reduced endurance, and reduced balance).

“I used to be an avid walker … I’d walk a couple miles a day, my husband would go with me after work. It’s something that we both enjoy doing very much after a long day, and just to spend time together. I found that since everything’s been happening, those walks got shorter and shorter, and then, now, they’re pretty much nonexistent.” (US014)

Role Functioning

All participants reported that their SCLC symptoms limited their ability to work or participate in hobbies [“I'm on a short-term disability right now” (USA3)] and that these limitations on work or hobbies have negatively affected their quality of life [“I don't play basketball anymore, which I really, really enjoy a lot” (US008)].

Difficulty Sleeping

Many participants reported difficulty sleeping. Some participants stated that SCLC symptoms, particularly coughing and pain, interfered with their sleep [“My coughing usually wakes me up in the middle of the night several times, so I get really unrested sleep, and I wake up feeling very exhausted” (US006)]. Participants also reported changes in sleep patterns not associated with symptoms [“It might be two hours here, two hours there… It’s interrupted. It’s never a steady solid eight hours of sleep” (USA3)].

Weight Loss

Additionally, participants discussed weight loss due to eating less, and that eating less was caused by a range of symptoms, including appetite loss [“You don’t think about eating when your chest is hurting or you feel like this heaviness or you feel tired” (US003)].

Themes

The following three themes that reflect the relationship between concepts were identified: the co-occurrence of symptoms (symptoms either occurring spontaneously or causing one another); regulating activities by breaking them down and/or pacing them; and the wide variation in the intensity, frequency, and duration of symptoms.

Most participants discussed that it was common for some clusters of symptoms to co-occur, such as cough, chest pain, and difficulty breathing [“When you cough, sometimes your chest hurts, and you just feel like you’re gasping for breath” (US003)]. Many participants also reported that one symptom may cause another [“When I have a long coughing episode my back starts to hurt” (US011)].

All participants reported breaking down and pacing activities to complete them [“I actually have to stop after a half a flight of stairs going up” (USA2)]. Participants often compared life before and after diagnosis, in terms of how activities are broken down and paced.

“Come spring you go outside and you hang your plants and you hang your lights around the deck and you clean up and wipe the table down, get the fire pit out and stuff. Well, I could do that all in one day. Where now that might take me three or four weekends to do, like three or four Saturdays. I would only maybe hang the lights and then have to take a breath – a rest.” (SD-03).

Across participants, as well as within their own individual patient experiences, there was wide variation in the intensity, duration, and frequency of symptoms.

Some patients reported that symptom intensity could be unpredictable. One participant discussed their experience with chest pain in relation to standard pain rating scales, stating, “There’s no rhyme or reason why it’s a one or a ten or a five or in between on the scale of pain. It fluctuates all between – sometimes I have good days and sometimes bad days” (USA3). Other patients reported that some symptoms were regularly mild, moderate, or severe.

Regarding symptom frequency, several patients used the word “random” to describe how often they experience symptoms [“I just never know when I’m going to feel [tired]. It’s just very sporadic, and it depends on what I do on a daily basis” (SD-01)]. Other patients reported a standard frequency of symptoms. For instance, one patient reported coughing up blood “a few times a week” (US004) and another patient reported it occurring “a couple of times a day” (US005).

Across participants, a wide range of duration of symptoms was reported. For instance, some patients reported difficulty breathing as lasting seconds while others reported it lasting months. Some patients reported that the duration of their own symptoms could fluctuate widely. One patient explained how the duration of their difficulty breathing fluctuated daily, stating “Every time, it’s different. It could last a whole day or even more… or it could be really quick. It would be maybe a couple of hours until I get my breath, and then it improves a little bit” (US007).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that people living with SCLC experience considerable and significant symptoms and impacts, including physical and role functioning challenges, that affect their quality of life. At the time of this writing, this research is the first study to use rigorous qualitative methods to create a conceptual model that describes how people living with SCLC experience this aggressive and deadly disease. This model will be used to inform the selection of PRO items from existing instruments and/or the design of a PRO questionnaire for a future SCLC clinical trial, helping to support the content validity of the questionnaires used in the trial and ensuring that the questionnaires and items selected are appropriately targeted to the population. This conceptual model could also be used to inform future patient-centered research in SCLC clinical trials.

Thematic findings around the co-occurrence of symptoms, breaking down and pacing activities, and the wide variation in symptoms are supported by studies focused on NSCLC [21, 33,34,35]. The symptom concepts we identified also aligned with those cited in the qualitative lung cancer literature [19, 35,36,37,38,39,40]. One study specified using concept elicitation as a method to explore symptoms of NSCLC through qualitative interviews to inform the development of the NSCLC-SAQ [20]. The core disease-related symptoms cited in that study overlap with those identified in this study, with differences mainly limited to those of granularity (e.g., our model specifies difficulty breathing at rest versus difficulty breathing due to exertion) or to the organization of concepts (e.g., our model specifies chest pain and arm/shoulder pain as organ-related symptoms, whereas the symptom concepts used to inform the NSCLC-SAQ group all types of pain under one domain) [20]. Further research could be conducted with patients to clarify what level of nuance is necessary to capture their experience.

Participants in this study highlighted specific impacts on movement related to physical functioning (reduced bending over, reduced squatting, and reduced balance) that have not been well-documented in the literature and that are not included in the NSCLC-SAQ or other PRO questionnaires used in clinical lung cancer research. Study participants also specified underlying factors limiting physical functioning defined by FDA as the ability to carry out daily activities [14] (reduced endurance, reduced strength, and reduced balance) as being important to them.

Preexisting PRO questionnaires commonly used in clinical lung cancer research would provide coverage for many of the disease-related symptoms (including cough, chest pain, difficulty breathing, pain, fatigue, dizziness, and appetite loss) and physical and role functioning impact concepts (including impact on daily activities, impact on work or school, weight loss, and difficulty sleeping) identified as part of this research. The most comprehensive coverage would be provided by the EORTC QLQ-C30, with the addition of bolt-on items from the EORTC LC-29 and the EORTC Item Library. Coughing up phlegm and wheezing are two key disease-related symptoms that do not appear to be covered by the EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC-LC29, EORTC LC-13, EORTC item library, FACT-G, FACT-L, LCSS, or MDASI. As disease-related symptoms, these may be important gaps in the current set of questionnaires and sources commonly used in SCLC clinical trials.

Our results suggest that the PRO questionnaires commonly used in lung cancer research may not capture all concepts that are important to patients, particularly the disease-related symptoms of wheezing and coughing up phlegm, or may not ask about the context of the experience (e.g., difficulty breathing at rest or when exercising). These conceptual gaps may impact the ability of the questionnaires to detect meaningful treatment benefit. Further qualitative research is needed to determine whether SCLC-specific PRO questionnaires are needed for use in clinical lung cancer research, or if the same PRO questionnaires would be relevant to and appropriate for SCLC and NSCLC patients.

The study results highlight potential challenges related to responding to current FDA guidance on PRO measurement in oncology clinical trials. First, commonly used PRO questionnaires recommended by the FDA to assess physical functioning do not include items that individually assess each major underlying factor or impact on movement that underpins physical functioning. Future research could explore the patient experience with physical functioning and be used to inform physical functioning measurement approaches that are more aligned with patients’ experiences.

Second, current FDA guidance encourages assessing disease-related symptoms and symptomatic adverse events separately. However, many patients in our study had received multiple rounds of treatment and reported (unprompted) that it was difficult to know which symptoms stem from the disease and which stem from treatment. In addition, many patients noted symptoms and impacts that stem from both the disease and treatment, such as fatigue, weight loss, and physical functioning challenges. This may pose trial design challenges, particularly around the timing of PRO assessments.

While this study contains robust qualitative data on the experience of patients living with SCLC, it may be limited by a mostly homogeneous population (i.e., mostly White, female, and non-Hispanic/Latino). Further qualitative research should be conducted with a larger, more diverse population to ensure that racial, ethnic, and gender-based experiences are explored. However, the information reported here is an important step toward capturing the patient voice in a disease area that has largely neglected their experience.

Conclusions

This study addresses a gap in the literature by providing a conceptual model of clinical treatment benefit in SCLC related to disease-related symptoms and impacts on patients including physical functioning, which is grounded in patients’ lived experiences. Moreover, this model aligns with current FDA guidance, focuses specifically on clinical treatment benefit, and thus can be used to inform the selection of PRO questionnaires or relevant PRO items to evaluate treatment benefit on symptoms and impacts that are important to patients living with SCLC.

References

Ferlay J, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. 2022 [cited 2022 August]; Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today.

Ferlay J, et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer. 2021;149(4):778–89.

Rudin CM, et al. Small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):1–20.

Byers LA, Gay CM, Nicholson A. Pathobiology and staging of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer, Alphen aan den Rijn; 2019.

Kalemkerian GP, et al. Small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(1):78–98.

Wang S, et al. Current diagnosis and management of small-cell lung cancer. In: Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier; 2019.

Thomas A, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of small cell lung cancer detected by CT screening. Chest. 2018;154(6):1284–90.

Dingemans A-M, et al. Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(7):839–53.

Horn L, et al. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(23):2220–9.

Tzelepis F, et al. Measuring the quality of patient-centered care: Why patient-reported measures are critical to reliable assessment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:831.

US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: Methods to identify what is important to patients. 2019. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/131230/download.

US Food and Drug Administration. Patient focused drug development: Incorporating clinical outcome assessments into endpoints for regulatory decision-making. 2019. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/132505/download.

US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: Collecting comprehensive and representative Input. Guidance for Industry, Food and Drug Administration Staff, and Other Stakeholders. 2020. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/139088/download.

US Food and Drug Administration. Core patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials: Guidance for industry (draft guidance). 2021; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/core-patient-reported-outcomes-cancer-clinical-trials.

Larson E, et al. When the patient is the expert: Measuring patient experience and satisfaction with care. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(8):563.

Kluetz PG, O’Connor DJ, Soltys K. Incorporating the patient experience into regulatory decision making in the USA, Europe, and Canada. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(5):e267–74.

Bouazza YB, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in the management of lung cancer: A systematic review. Lung Cancer. 2017;113:140–51.

Aumann I, et al. Treatment-related experiences and preferences of patients with lung cancer: A qualitative analysis. Health Expect. 2016;19(6):1226–36.

Belqaid K, et al. Dealing with taste and smell alterations-a qualitative interview study of people treated for lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1): e0191117.

Brown LM, et al. Health-related quality of life after lobectomy for lung cancer: conceptual framework and measurement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110(6):1840–6.

McCarrier KP, et al. Qualitative development and content validity of the Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Symptom Assessment Questionnaire (NSCLC-SAQ), a patient-reported outcome instrument. Clin Ther. 2016;38(4):794–810.

Small Cell Lung Cancer Working Group, Small Cell Lung Cancer Working Group Poster, in 13th Annual PRO Consortium Workshop, Critical Path Institute, April 13–14, 2022.

Yoo JS, et al. The association of physical function and quality of life on physical activity for non-small cell lung cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(10):4847–56.

Brédart A, et al. Interviewing to develop Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) measures for clinical research: eliciting patients’ experience. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):1–10.

Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat. 2016;5(1):1–4.

Kerr C, Nixon A, Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(3):269–81.

Harris PA, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95: 103208.

Harris PA, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Bryman A, Burgess B. Analyzing qualitative data. New York, NY: Routledge; 2002.

Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–46.

Bowling A. Research methods in health: Investigating health and health services. 3rd edn. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2009.

Klassen A, et al. Satisfaction and quality of life in women who undergo breast surgery: A qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9:11–8.

Borneman T, et al. A qualitative analysis of cancer-related fatigue in ambulatory oncology. Clin J Oncol Nursing. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1188/12.CJON.E26-E32.

Crandall K, et al. A qualitative study exploring the views, attitudes and beliefs of patients and health professionals towards exercise intervention for people who are surgically treated for lung cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(2): e12828.

Stowe E, Wagland R. A qualitative exploration of distress associated with episodic breathlessness in advanced lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;34:76–81.

Brown NM, et al. Supportive care needs and preferences of lung cancer patients: A semi-structured qualitative interview study. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(6):1533–9.

Chang P-H, et al. Exercise experiences in patients with metastatic lung cancer: A qualitative approach. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0230188.

Lathan CS, et al. Perspectives of African Americans on lung cancer: A qualitative analysis. Oncologist. 2015;20(4):393–9.

Linde P, et al. Unpredictable episodic breathlessness in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer: A qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(4):1097–104.

Shim J, et al. A systematic review of symptomatic diagnosis of lung cancer. Fam Pract. 2014;31(2):137–48.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients for participating in the interviews. We thank Jessica T. Markowitz, Natalie Thomas, and Gerrit Vandenberg for their assistance in conducting interviews and data analysis. We thank Lori Bacarella, Sara Strzok, and Zahava Rosenburg-Yunger for writing support.

Funding

This research was funded by EMD Serono Research & Development Institute, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany (CrossRef Funder ID: 10.13039/100004755). The journal’s Rapid Service fees have also been funded by EMD Serono.

Author Contributions

An-Chen Fu, Alissa Rams, Camilo Moulin, Danielle Altman, Elena Benincasa, Michael Schliting, Patrick Marquis, and Xinke Zhang contributed to the research design. Alissa Rams, Danielle Altman, Jessica Baldasaro, Patrick Marquis, and Samir Ali Ahmad contributed to interview conduct and data analysis. Vivek Pawar and all authors contributed to the interpretation of results and manuscript writing and development. Vivek Pawar and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Alissa Rams, Danielle Altman, Jessica Baldasaro, Patrick Marquis are employees of Modus Outcomes, Cambridge, MA, USA, and received funding for this research from EMD Serono Research & Development Institute, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany (CrossRef Funder ID: 10.13039/100004755); Samir Ali Ahmad was an employee of Modus Outcomes at the time this research was conducted. An-Chen Fu and Vivek Pawar are employees of EMD Serono Research & Development Institute, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany; Xinke Zhang was an employee of EMD Serono at the time this research was conducted. Michael Schliting, Elena Benincasa, and Camilo Moulin are employees of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Prior Presentation

Partial presentations of the work described herein took place at the Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research Annual Meeting in 2022 (Altman D, Fu AC, Marquis P, Rams A, Baldasaro J, Ali AS, Schlichting M, Zhang X. PCR179 Development of a Conceptual Model of the Patient Experience in Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC): A Qualitative Interview Study. Value in Health. 2022 Jul 1;25(7):S575).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Study documents, including the protocol, demographic and health information form, interview guide, screener, and informed consent and assent forms received ethical approval from WCG IRB (IRB20212620). This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. All participants provided informed consent/assent to participate in this study; written consent and assent were obtained from participants before proceeding with the interviews.

Data Availability

Data can be shared with qualified scientific and medical researchers, upon the researcher’s request, as necessary for legitimate research. Such requests should be submitted in writing to the data sharing portal of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. When Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany has a co-research, co-development, co-marketing, or co-promotion agreement, or when the product has been out-licensed, the responsibility for disclosure might be dependent on the agreement between parties. Under these circumstances, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany will endeavor to gain agreement to share data in response to requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Altman, D.E., Zhang, X., Fu, AC. et al. Development of a Conceptual Model of the Patient Experience in Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Qualitative Interview Study. Oncol Ther 11, 231–244 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-023-00223-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-023-00223-w