Abstract

The coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a significant impact on patients with underlying malignancy. In this article, we summarize emerging data related to patients with cancer and COVID-19. Among patients with COVID-19, a higher proportion have an underlying diagnosis of cancer than seen in the general population. Also, patients with malignancy are likely to be more vulnerable than the general population to contracting COVID-19. Mortality is significantly higher in patients with both cancer and COVID-19 compared with the overall COVID-19-positive population. The early months of the pandemic saw a decrease in cancer screening and diagnosis, as well as postponement of standard treatments, which could lead to excess deaths from cancer in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Pooled analyses show that approximately 1–3.9% of patients with COVID-19 have cancer. The proportion of patients with underlying malignancy was found to be much higher (7.3–20.3%) in subsets of patients with COVID-19 who were critically ill or died. |

Patients with cancer have a higher risk (0.79–8.3%) of developing SARS-CoV-2 infection than the general population. |

Patients with cancer who develop COVID-19 tend to have much worse outcomes (mortality ranging from 11.4% to 35.5%) compared with those without cancer. |

There are conflicting data regarding the impact of recent systemic anticancer therapy on the outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection. |

The pandemic has had a negative impact on cancer clinical trials. |

The use of technology, including telemedicine, has increased since the start of the pandemic. |

Shunting of healthcare resources to frontline management of COVID-19 has resulted in a decrease in cancer screening and has also impacted cancer treatment. This could manifest in excess mortality from cancer in the near future. |

Background

The novel coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the beta-coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was initially reported in December 2019 from Wuhan, China. It was soon declared a pandemic, rapidly spreading around the world and greatly impacting human society, especially the healthcare systems. The incidence of new cases of COVID-19 has recently declined in many countries in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, but continues to be high in other countries such as the USA, Brazil, India, and Russia. Further, some countries are again reporting an increase in the number of new cases after a period of control.

Cancer care and research too have been severely disrupted as a result of COVID-19 [1]. This article summarizes key observations and lessons from the impact of the pandemic on cancer treatment and trials during the first 6 months since its outbreak.

What Proportion of Patients with COVID-19 Have Underlying Cancer?

Emerging data show that among patients with COVID-19, a higher proportion have an underlying diagnosis of cancer than seen in the general population. Among 1590 patients with COVID-19 in a Chinese hospital, 18 (1%; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.61–1.65) had a history of cancer, which was higher than the incidence of cancer in the overall Chinese population [2]. An analysis of 11 early retrospective studies from China involving 3661 patients showed that the overall pooled prevalence of cancer in patients with COVID-19 was 2% (95% CI, 2.0–3.0) [3], while a larger meta-analysis involving a total of 32,404 patients from nine countries estimated that the pooled prevalence of cancer among the COVID-19-infected population was 3.5% (95% CI 1.70–5.80) [4]. Another meta-analysis of 18 studies with14,558 patients with COVID-19 showed that 3.9% (95% CI 2.5–5.4) of them had cancer [5].

The proportion of patients with underlying malignancy was found to be much higher in subsets of patients with COVID-19 who were critically ill or died. Among 1591 patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy, 81 (8%) had underlying malignancy [6]. Among 82 Chinese patients who died of COVID-19, cancer was found to be present in 7.3% [7]. A chart review of 355 patients in Italy who had died of COVID-19 showed that 72 (20.3%) had active cancer [8].

What Proportion of Patients with Cancer Develop COVID-19?

Patients with active malignancy are likely to be more vulnerable than the general population to infections, including those caused by respiratory viruses [9]. There could be several reasons for this, including an immunocompromised state brought about by the disease itself [10], or by cancer treatment [11].

Out of 1524 patients with cancer at a single institution in China, 12 (0.79%) were found to be positive for SARS-CoV-2, proportionately higher than the general population [12]. At a single institution in Spain, COVID-19 was diagnosed in 45 out of 1069 (4.2%) patients with cancer [13]. Out of 200 pediatric patients on anticancer therapy tested for SARS-CoV-2, nine (4.5%) were found to be positive for the infection [14]. Among 24 patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer in a single center in Italy, two (8.3%) were found to be positive for COVID-19 [15].

To summarize the intersection of the incidence of cancer and COVID-19, there is evidence that a significant subset of patients with COVID-19 have underlying malignancy, and patients with cancer have a higher risk of developing SARS-CoV-2 infection than the general population. However, given our inadequate capacity for systematic testing at a population scale, limited availability of published data, asymptomatic nature of the SARS-CoV-2 infection in a significant proportion of affected people, and the false-negative results of some of the tests performed, there are insufficient data to make a firm conclusion regarding the quantum of excess risk.

Do Patients with COVID-19 and Underlying Malignancy Have Worse Outcomes?

The case fatality ratio (CFR) of COVID-19 in the overall population is not precisely known [16]. Current estimates range from 0.25% to 3.0% [17], although a meta-analysis of 73 studies involving 10,402 patients estimated a higher mortality rate of 7% [18]. In contrast, patients with cancer who develop COVID-19 tend to have much worse outcomes, with mortality ranging from 11.4% to 35.5% (see Table 1) in selected retrospective studies.

A study from nine hospitals in Wuhan which included 232 patients with cancer and COVID-19 found that patients with cancer were more likely to have severe infection than patients without cancer, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.61 (95% CI 2.59–5.04) [19].

In an analysis from a New York hospital system of patients with COVID-19 and underlying malignancy, a CFR of 25% (41/164) was noted for solid cancers and 37% (20/54) for hematological malignancies, with older age, multiple comorbidities, need for intensive care support, and elevated levels of D-dimer, lactate dehydrogenase, and lactate being significantly associated with mortality [20].

There is also evidence that COVID-19 patients with hematological malignancies are generally at greater risk than those with solid cancers, and those with recently diagnosed cancer have worse outcomes than those with a remote diagnosis. A recent analysis of medical records of 10,926 adults in England with linked COVID-19 deaths found that the age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratio for COVID-19 death among patients with hematological malignancy diagnosed within the past year was 3.02 (95% CI 2.24–4.08), decreasing to 2.56 (95% CI 2.17–3.06) if the diagnosis was made 1–4.9 years ago; among those with a diagnosis of non-hematologic malignancy within the past year, the hazard ratio was 1.81 (95% CI 1.58–2.07), which decreased to 1.20 (95% CI 1.10–1.32) if the diagnosis was made 1–4.9 years ago [21].

A remarkable and clinically significant observation from 14 hospitals in Hubei, China is that COVID-19-positive patients with cancer involving the lung (either primary or metastases) seem to have a poorer clinical outcome than those without tumoral lung involvement [22, 23]. A retrospective chart review of 1878 patients with COVID-19 at a Spanish hospital found that 17 had lung cancer, of whom 9 died [24].

Among 1018 patients with both COVID-19 and cancer, independent factors associated with increased 30-day mortality were age, male sex, former smoking, and worse Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status [25].

Fortunately, pediatric cancer patients who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 tend to generally have a benign course of infection [26].

Does Recent Anticancer Therapy Impact Outcomes of Patients with Cancer and COVID-19?

There are conflicting data concerning the impact of recent systemic anticancer therapy on COVID-related mortality.

A prospective observational study from the UK Coronavirus Cancer Monitoring Project (UKCCMP) found that among 800 patients with active cancer and a positive SARS-CoV-2 real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay, the receipt of cancer treatment (chemotherapy, immunotherapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy, or radiotherapy) within the past 4 weeks had no significant effect on mortality from COVID-19 after adjusting for variables such as age, gender, and comorbidities [27]. Similarly, a study from Madrid, one of the epicenters of the pandemic, showed that patients with COVID-19 and cancer who received chemotherapy did not have an increase in mortality, and the authors even hypothesized that chemotherapy could decrease COVID-19-induced inflammation [13]. Another study found that treatment with cytotoxic agents, anti-PD1/PDL1, anti-CD20, antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors, or mTOR inhibitors were not associated with an increased risk of death in patients with cancer and SARS-CoV-2 positivity [28]. In a cohort study of 928 cancer patients from the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) database, 30-day all-cause mortality in patients with cancer infected with SARS-CoV-19 was not found to be associated with the type of cancer, recent anticancer therapy, or recent surgery [29]. Intriguingly, initial data from the Thoracic Cancers International COVID-19 Collaboration (TERAVOLT) registry indicate that patients on tyrosine kinase inhibitors appear to be at decreased risk for hospital admission [30].

On the other hand, a retrospective analysis from nine hospitals in Hubei, China, which included 205 patients with cancer and laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, found that those receiving chemotherapy within 4 weeks before symptom onset had a higher risk of death during hospital admission [31]. The French experience at Gustave Roussy showed that those patients who had received chemotherapy within the past 3 months had a poorer outcome compared with patients who received either targeted agents or immunotherapy [32]. The TERAVOLT registry too reported that chemotherapy within 3 months of COVID-19 diagnosis was associated with increased risk of mortality [30].

In summary, there is evidence from retrospective analyses that COVID-19 patients with cancer have worse outcomes and more severe disease compared with COVID-19 patients without cancer. This could be especially true for patients with primary or secondary involvement of the lung, and those with hematological malignancy. However, because there are likely to be some confounding factors in these analyses, it is currently not possible to quantify with certainty the excess mortality in cancer patients over a propensity-matched control population.

Impact of the Pandemic on Cancer Trials

The pandemic has had a considerable negative impact on cancer clinical trials, for several reasons [33, 34], including research staff being redeployed to frontline clinical activities, global travel restrictions, reduction in the numbers of eligible patients visiting hospitals, and other factors [35]. As the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak spread around the world, it resulted in a considerable dip in enrollment in ongoing studies, especially during periods of high transmission. Unger et al. reported that while 1431 patients were enrolled in ongoing SWOG Cancer Research Network studies during weeks 1–11 of 2020, this number dropped to 439 during weeks 12–17, coinciding with increased COVID-19 incidence across the United States [36]. A global analysis found a 60% decrease in enrollment of new patients in oncology clinical trials in April 2020 compared with April 2019 [37]. On the other hand, a large number of COVID-19-related clinical trials have been launched, many of them testing repurposed anticancer drugs [38].

There could be increased protocol deviations as patients miss hospital visits, as well as delayed data reporting, potentially impacting patient safety. Of particular concern are immunotherapy trials, where fever and pneumonitis are expected complications of therapy [39] and might be difficult to discern from symptoms of COVID-19.

In recent years, telemedicine solutions have been implemented in Australia to allow patients in more remote locations to have access and to boost recruitment to major adjuvant breast cancer trials such as MonarchE [40], a trend that is likely to intensify during the pandemic and to continue in the post-pandemic era.

There has also been a significant impact on trial processes [41], including monitoring and audit, with new remote systems being required and deployment of staff to working from home conditions. Consequently, the pandemic has generated calls to streamline cancer trial methodology and paperwork, and to reduce the number of mandatory hospital visits [42].

Impact of the Pandemic on Cancer Treatment

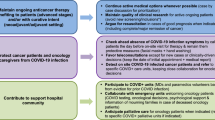

Cancer clinics worldwide responded to the pandemic by implementing processes such as segregated workflow [43], prioritizing certain subgroups of cancer patients for immediate treatment while postponing therapy for other groups [44], modifying certain treatment protocols, [45, 46] incorporating telemedicine into their workflow [47], and other measures [48, 49]. Mauri et al. [50] reviewed 63 guidelines from professional societies around the world and summarized key recommendations.

In hospitals serving populations with a high caseload of SARS-CoV-2 infection, such as New Delhi, Mumbai, Milan, Madrid, and New York, medical resources were preferentially deployed to treat patients with COVID-19, potentially compromising routine activities such as cancer screening and therapy. Another concern that physicians in charge of metastatic cancer patients have had during the pandemic is in selecting the ideal systemic treatment from different available alternatives, keeping in view emerging data that hospital admission or recurrent hospital visits could be potential risk factors for cancer patients to acquire SARS-CoV-2 infection [12]. Patients with cancer being treated in low- and middle-income countries have faced particularly difficult challenges during the pandemic [51,52,53].

In the field of genitourinary tumors, where different treatment strategies including chemotherapy, targeted therapies, hormone therapies, immunotherapy, or radionuclides can be offered to patients, recommendations favor the use of regimens with lower rates of cytopenia during this pandemic [54].

Given their widespread use in oncology as well as their immunomodulatory properties, the use of checkpoint inhibitors during the pandemic has drawn attention. Initial data show that administering immunotherapeutic agents to patients with cancer may not worsen their outcomes [27]. However, additional research is needed, and careful patient selection and informed discussion should take place before using these agents [55].

Increased Adoption of Telemedicine

Rapid implementation of telehealth consultations, either by phone or video link, has allowed potentially vulnerable patients to be monitored and supported at home, rather than having to travel to hospitals for follow-up. Difficulties arise with the inability to fully examine patients, technology failures, and lack of training of clinical staff in the nuances of communication at a distance, including maintaining privacy. Attention to appropriate positioning, eye contact, lighting, sound, and expressions of empathy can help patients have more satisfying interactions over video. Key to the success of telemedicine has been changes to reimbursement structures, as well as the development of suitable technology. It is important to ensure that the use of patient-centered measures such as telemedicine continues to be part of the standard oncology clinical practice and clinical trials even after the pandemic subsides [56].

Could There Be an Excess of Cancer Deaths in the Near Future?

Emerging data indicate that fewer cases of cancer were diagnosed during the early phases of the pandemic [57], likely as a result of travel restrictions and the avoidance of hospital visits by patients for regular cancer screening or investigation of new symptoms. One analysis from England and Northern Ireland found a 45–66% reduction in admissions for chemotherapy and 70–89% decline in urgent referrals for early cancer diagnosis during the early phase of the pandemic [58]. This postponement of normal cancer screening activities and timely treatment could lead to excess deaths from cancer in the future, with one estimate suggesting a 1% increase in deaths from breast and colorectal cancer over the next decade in the USA alone, i.e. about 10,000 excess deaths [59].

There is an urgent need to implement policies and procedures to limit the collateral damage of COVID-19 on cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment [60], especially since there are increasing data to show that careful patient selection and implementation of rigorous infection control measures may allow safe delivery of oncology therapy during the pandemic, with little additional risk to patients.

Efforts to collect large-scale and long-term data about the impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer, such as the OnCovid observational study, should be encouraged [61].

Future Directions

This global pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on human society, culture, and medical practice. It is likely that future oncology care will increasingly incorporate digital pathology [62], telemedicine [63], and other technologies. Virtual multidisciplinary team meetings, supplemented by electronic patient-reported outcome measures, may allow patients with rarer cancers and their clinicians to receive expert input while reducing the impact of travel, and facilitate more equitable access to clinical trials.

References

Saini KS, de Las Heras B, de Castro J, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer treatment and research. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(6):e432–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30123-X.

Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6.

Desai A, Sachdeva S, Parekh T, Desai R. COVID-19 and cancer: lessons from a pooled meta-analysis. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:557–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/GO.20.00097.

Ofori-Asenso R, Ogundipe O, Agyeman AA, et al. Cancer is associated with severe disease in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1047. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2020.1047(Published 2020 May 18).

Singh AK, Gillies CL, Singh R, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and their association with mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 23]. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.14124.

Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 6]. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574–81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394.

Zhang B, Zhou X, Qiu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 82 cases of death from COVID-19. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235458. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235458(Published 2020 Jul 9).

Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 23]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4683.

von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Berger A, Christopeit M, et al. Community acquired respiratory virus infections in cancer patients—guideline on diagnosis and management by the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society for haematology and Medical Oncology. Eur J Cancer. 2016;67:200–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.08.015.

Morrison VA. Infections in patients with leukemia and lymphoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2014;161:319–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04220-6_11.

Verma R, Foster RE, Horgan K, et al. Lymphocyte depletion and repopulation after chemotherapy for primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-015-0669-x(Published 2016 Jan 26).

Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, Xie C. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 25]. JAMA Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980.

Rogado J, Obispo B, Pangua C, et al. Covid-19 transmission, outcome and associated risk factors in cancer patients at the first month of the pandemic in a Spanish hospital in Madrid [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 25]. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-020-02381-z.

Hrusak O, Kalina T, Wolf J, et al. Flash survey on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infections in paediatric patients on anticancer treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2020;132:11–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.03.021.

Di Lorenzo G, Buonerba L, Ingenito C, et al. Clinical characteristics of metastatic prostate cancer patients infected with COVID-19 in South Italy [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 22]. Oncology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1159/000509434.

Böttcher L, Xia M, Chou T. Why case fatality ratios can be misleading: individual- and population-based mortality estimates and factors influencing them [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 18]. Phys Biol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1088/1478-3975/ab9e59.

Wilson N, Kvalsvig A, Barnard LT, Baker MG. Case-fatality risk estimates for COVID-19 calculated by using a lag time for fatality. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(6):1339–441. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2606.200320.

Grant MC, Geoghegan L, Arbyn M, et al. The prevalence of symptoms in 24,410 adults infected by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis of 148 studies from 9 countries. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234765. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234765(Published 2020 Jun 23).

Tian J, Yuan X, Xiao J, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer in Wuhan, China: a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 29]. Lancet Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30309-0.

Mehta V, Goel S, Kabarriti R, et al. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York Hospital System [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 1]. Cancer Discov. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.cd-20-0516.

Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. OpenSAFELY: factors associated with COVID-19 death in 17 million patients [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 8]. Nature. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4.

Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: a multicenter study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(6):783–91. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0422.

Wang B, Huang Y. Which type of cancer patients are more susceptible to the SARS-COX-2: Evidence from a meta-analysis and bioinformatics analysis [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 15]. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;153:103032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103032.

Rogado J, Pangua C, Serrano-Montero G, et al. Covid-19 and lung cancer: a greater fatality rate? [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 30]. Lung Cancer. 2020;146:19–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.05.034.

Warner JL, Rubinstein S, Grivas P, et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer: data from the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19). J Clin Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2020.38.18_suppl.lba110.

Rossoff J, Patel AB, Muscat E, Kociolek LK, Muller WJ. Benign course of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a series of pediatric oncology patients [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 23]. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28504.

Lee LYW, Cazier JB, Starkey T, et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1919–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31173-9.

Assaad S, Avrillon V, Fournier ML, et al. High mortality rate in cancer patients with symptoms of COVID-19 with or without detectable SARS-COV-2 on RT-PCR [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 7]. Eur J Cancer. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.05.028.

Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1907–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9.

Garassino MC, Whisenant JG, Huang LC, et al. COVID-19 in patients with thoracic malignancies (TERAVOLT): first results of an international, registry-based, cohort study [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 12]. Lancet Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30314-4.

Yang K, Sheng Y, Huang C, et al. Clinical characteristics, outcomes, and risk factors for mortality in patients with cancer and COVID-19 in Hubei, China: a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 29]. Lancet Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30310-7.

Barlesi F, Foulon S, Bayle A, et al. Abstract CT403—outcome of cancer patients infected with COVID-19, including toxicity of cancer treatments. In: AACR virtual meeting; 2020. https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/9045/presentation/10935. Accessed 13 July 2020.

Moujaess E, Kourie HR, Ghosn M. Cancer patients and research during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of current evidence. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;150:102972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.102972.

Upadhaya S, Yu JX, Oliva C, Hooton M, Hodge J, Hubbard-Lucey VM. Impact of COVID-19 on oncology clinical trials. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(6):376–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41573-020-00093-1.

Tarantino P, Trapani D, Curigliano G. Conducting phase 1 cancer clinical trials during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-related disease pandemic. Eur J Cancer. 2020;132:8–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.03.023.

Unger JM, Blanke CD, LeBlanc M, Hershman DL. Association of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak with enrollment in cancer clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e2010651. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10651(Published 2020 Jun 1).

COVID-19 and Clinical Trials: The Medidata perspective release 5.0. https://www.medidata.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/COVID19-Response5.0_Clinical-Trials_20200518_v2.2.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2020.

Saini KS, Lanza C, Romano M, et al. Repurposing anticancer drugs for COVID-19-induced inflammation, immune dysfunction, and coagulopathy [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 22]. Br J Cancer. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-0948-x.

Tagliamento M, Spagnolo F, Poggio F, et al. Italian survey on managing immune checkpoint inhibitors in oncology during COVID-19 outbreak [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 14]. Eur J Clin Investig. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13315.

Sabesan S, Zalcberg J. Telehealth models could be extended to conducting clinical trials-a teletrial approach. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(2):e12587. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12587.

Tiu C, Shinde R, Yap C, et al. A risk-based approach to experimental early phase clinical trials during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):889–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30339-9.

Karzai F, Madan RA, Dahut W. The world of clinical trial development post-Covid-19: lessons learned from a global pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 5]. Clin Cancer Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-1914.

National University Cancer Institute of Singapore (NCIS) Workflow Team. A segregated-team model to maintain cancer care during the COVID-19 outbreak at an academic center in Singapore. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(7):840–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.306.

Beddok A, Calugaru V, Minsat M, et al. Post-lockdown management of oncological priorities and postponed radiation therapy following the COVID-19 pandemic: experience of the institut curie [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 5]. Radiother Oncol. 2020;150:12–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2020.05.043.

Gasparri ML, Gentilini OD, Lueftner D, Kuehn T, Kaidar-Person O, Poortmans P. Changes in breast cancer management during the Corona Virus Disease 19 pandemic: an international survey of the European Breast Cancer Research Association of Surgical Trialists (EUBREAST). Breast. 2020;52:110–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2020.05.006.

Akula SM, Abrams SL, Steelman LS, et al. Cancer therapy and treatments during COVID-19 era. Adv Biol Regul. 2020;77:100739.

Lonergan PE, Washington Iii SL, Branagan L, et al. Rapid utilization of telehealth in a comprehensive cancer center as a response to COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 21]. J Med Internet Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.2196/19322.

von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Vehreschild JJ, Cornely O, et al. Frequently asked questions regarding SARS-CoV-2 in cancer patients-recommendations for clinicians caring for patients with malignant diseases. Leukemia. 2020;34(6):1487–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0832-y.

Cai J, Zheng L, Lv D, et al. Prevention and control strategies in the diagnosis and treatment of solid tumors in children during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 12]. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/08880018.2020.1767740.

Mauri D, Kamposioras K, Tolia M, Alongi F, Tzachanis D, International Oncology Panel and European Cancer Patient Coalition Collaborators. Summary of international recommendations in 23 languages for patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):759–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30278-3.

Belkacemi Y, Grellier N, Ghith S, et al. A review of the international early recommendations for departments organization and cancer management priorities during the global COVID-19 pandemic: applicability in low- and middle-income countries [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 8]. Eur J Cancer. 2020;135:130–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.05.015.

Trehan A, Jain R, Bansal D. Oncology care in a lower middle-income country during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(8):e28438. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28438.

de Melo AC, Thuler LCS, da Silva JL, et al. Cancer inpatient with COVID-19: a report from the Brazilian National Cancer Institute. Preprint. medRxiv:2020.06.27.20141499. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.27.20141499.

Gillessen S, Powles T. Advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with urological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol. 2020;77(6):667–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.026.

Maio M, Hamid O, Larkin J, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer therapy in the COVID-19 era [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 15]. Clin Cancer Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-1657.

Putora PM, Baudis M, Beadle BM, El Naqa I, Giordano FA, Nicolay NH. Oncology informatics: status quo and outlook. Oncology. 2020;98(6):329–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000507586.

Dinmohamed AG, Visser O, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2020 May 4]. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):750–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30265-5.

Lai AG, Pasea L, Banerjee A, et al. Estimating excess mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity in the COVID-19 emergency. Preprint. medRxiv:2020.05.27.20083287. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.27.20083287.

Sharpless NE. COVID-19 and cancer. Science. 2020;368(6497):1290. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd3377.

The Lancet Oncology. Safeguarding cancer care in a post-COVID-19 world. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):603. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30243-6.

The ONCOVID Study. https://www.oncovid.net/the-oncovid-study. Accessed 13 July 2020.

Hanna MG, Reuter VE, Ardon O, et al. Validation of a digital pathology system including remote review during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 22]. Mod Pathol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0601-5.

Chwistek M. “Are you wearing your white coat?”: telemedicine in the time of pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 25]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.10619.

Trapani D, Marra A, Curigliano G. The experience on coronavirus disease 2019 and cancer from an oncology hub institution in Milan, Lombardy Region. Eur J Cancer. 2020;132:199–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.04.017.

Robilotti EV, Babady NE, Mead PA, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 24]. Nat Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0979-0.

Horn L, Whisenant JG, Torri V, et al. Thoracic cancers international COVID-19 collaboration (TERAVOLT): impact of type of cancer therapy and COVID therapy on survival. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(18_suppl):LBA111.

Scarfò L, Chatzikonstantinou T, Rigolin GM, et al. COVID-19 severity and mortality in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a joint study by ERIC, the European Research Initiative on CLL, and CLL Campus [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 9]. Leukemia. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0959-x.

Russell B, Moss C, Papa S, et al. Factors affecting COVID-19 outcomes in cancer patients—a first report from Guys Cancer Centre in London. Preprint. medRxiv:2020.05.12.20094219. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.12.20094219.

Zhang H, Wang L, Chen Y, et al. Outcomes of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in 107 patients with cancer from Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 23]. Cancer. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33042.

Luo J, Rizvi H, Preeshagul IR, et al. COVID-19 in patients with lung cancer [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 16]. Ann Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.06.007.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding was received from any source. No Rapid Service Fee was received by the journal for the publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Kamal S. Saini, Begoña de las Heras, Manuela Leone, and Marco Romano conceptualized the manuscript, all authors provided significant inputs, Begoña de las Heras and Kamal S. Saini wrote the manuscript, and all authors reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript. All authors have reviewed the final version of this manuscript and provided their consent to publish.

Disclosures

Kamal S. Saini reports consulting fees from the European Commission outside the submitted work. Frances Boyle reports honoraria and advisory board fees from Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, Eisai, and Lilly outside the submitted work. She is Director of the Pam McLean Communications Centre at the University of Sydney, involved in developing and providing telehealth training, outside the submitted work. Evandro de Azambuja reports honoraria and advisory board fees from Roche/GNE, Novartis, and Seattle Genetics; travel grants from Roche/GNE, GSK, and Novartis; and a research grant to the institution from Roche/GNE, AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, and Servier outside the submitted work. Enrique Grande has received honoraria for ad boards, meetings, and/or lectures from Pfizer, BMS, IPSEN, Roche, Eisai, EUSA Pharma, MSD, Sanofi, AAA, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Lexicon, and Celgene and has received unrestricted research grants from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, MTEM/Threshold, Roche, Ipsen, and Lexicon outside the submitted work. Sudeep Gupta reports research funding to the institution from Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, Eisai, Lilly, OncoStem Diagnostics, and Celltrion outside the submitted work. Begoña de las Heras, Felipe Ades, Ivana Bozovic-Spasojevic, Marco Romano, Marta Capelan, Rajeev Prasad, Pugazhenthi Pattu, Christophe Massard, Chia Portera, Monika Lamba Saini, Brajendra Prasad Singh, Ramachandran Venkitaraman, Richard McNally, and Manuela Leone have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data and references mentioned in this manuscript are from publicly available sources. Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12706601.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de las Heras, B., Saini, K.S., Boyle, F. et al. Cancer Treatment and Research During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experience of the First 6 Months. Oncol Ther 8, 171–182 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-020-00124-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-020-00124-2