Abstract

Purpose of Review

Examining what older women know and perceive about mammography screening is critical for understanding patterns of under- and overuse, and concordance with screening mammography guidelines in the USA. This narrative review synthesizes qualitative and quantitative evidence around older women’s perspectives toward mammography screening.

Recent Findings

The majority of 43 identified studies focused on promoting mammography screening in women of different ages, with only four studies focusing on the overuse of mammography in women ≥ 70 years old. Older women hold positive attitudes around screening, perceive breast cancer as serious, believe the benefits outweigh the barriers, and are worried about undergoing treatment if diagnosed. Older women have limited knowledge of screening guidelines and potential harms of screening.

Summary

Efforts to address inequities in mammography access and underuse need to be supplemented by epidemiologic and interventional studies using mixed-methods approaches to improve awareness of benefits and harms of mammography screening in older racially and ethnically diverse women. As uncertainty around how best to approach mammography screening in older women remains, understanding women’s perspectives along with healthcare provider and system-level factors is critical for ensuring appropriate and equitable mammography screening use in older women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in the USA, representing nearly 30% of all new female cancer diagnoses in 2020 [1]. Mammography screening is critical for the early detection of breast cancer and is associated with a 20% reduction in mortality for women ages 50–74 years [2, 3]; however, the margin of benefit is highly dependent on a woman’s age, personal risk of breast cancer, and overall health [4,5,6]. Although the incidence of breast cancer generally increases with age, the long-term benefits of mammography may be limited in older women due to increased comorbidities and diminished life expectancy [7,8,9]. Professional guidelines do not support routine mammography screening for older women. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) makes no breast cancer screening recommendations for women ≥ 75 years due to insufficient empirical evidence [10, 11] while the American Cancer Society recommends biennial screening for women with a life expectancy greater than 10 years [12]. More recently, the American College of Physicians supported the discontinuation of mammography in older women at average risk for breast cancer, such as women without a strong family history or genetic susceptibility [13].

Efforts to ensure equitable access to healthcare have focused on underuse—gaps in care where patients have not received or have limited access to care that will benefit them [14, 15]. Less attention has focused on healthcare overuse—care where the harms outweigh the benefits or the balance between benefits and harm is unknown [15]. Healthcare overuse more broadly is pervasive within the healthcare system and older adults may be particularly vulnerable to this phenomenon. Mammography screening is a prime example of healthcare overuse for older women with life expectancies less than 10 years. The potential harms of mammography screening are often immediate and include anxiety around false positive results, unnecessary breast biopsies, false assurance from false-negative results, and overdiagnosis and treatment of tumors that would not have resulted in death [5, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Importantly, cancer treatments ranging from surgery to hormonal therapy are associated with greater complication in the presence of comorbidities, which is more prevalent in older adults [16]. Although professional guidelines vary in their recommendations about mammography screening for older women, most agree that the decision to continue or discontinue screening should be individualized, weighing the potential benefits and harms while considering life expectancy, comorbidity burden, and women’s preferences [10,11,12,13]. To this end, the benefits of screening mammography in older women need to be considered against the more immediate harms.

Existing research around mammography screening use and overuse in older women has primarily focused on exploring provider- and organizational-level factors driving lack of adherence to guidelines, clinical and sociodemographic factors impacting utilization/adherence to mammography screening, and implications for associated morbidity, mortality, and psychological well-being [6, 23,24,25]. Among the few studies on older women’s perspectives toward mammography screening, the majority were conducted outside of the USA [26,27,28,29] or prior to changes in breast cancer screening guidelines over the last decade [30,31,32]. Importantly, there is a lack of a comprehensive and recent synthesis of evidence on what older women know and perceive about mammography screening, which is critical for designing strategies and interventions to address screening mammography inequities related to use and overuse [5, 33, 34]. To address this critical gap, this review aims to describe the breadth of empirical research on older women’s perspectives around screening mammography use and overuse in the USA.

Methods

We conducted a narrative review of the literature to synthesize quantitative and qualitative studies of older women’s perspectives toward mammography screening including knowledge, attitudes, experiences, and health beliefs. Databases PubMed, Medline, and PsychINFO were electronically searched to identify quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies performed in the USA reporting original data, applying the following search strategy: (women* OR woman*) AND (knowledge OR awareness OR perspective OR understanding OR perceptions OR attitude OR belief) AND (mammogra* OR breast screening OR breast cancer screening).

We limited our search to original peer-reviewed studies published in English between January 2009 and March 2020 with full-text availability. The decision to limit our search to studies published after 2009 was to both capture recent literature and coincide with the USPSTF guideline change for mammography screening in women aged ≥ 75 years [10, 11]. While guidelines are specific to women aged ≥ 75 years, we expanded the definition of older women to women ages ≥ 65 years to be more inclusive of a larger number of relevant studies focusing on aging populations. Where the specific age distribution was unavailable, we used the overall sample age distribution and included studies where at least 25% of the sample were women ≥ 60 or the mean age was ≥ 55 to ensure sufficient representation of older women and their perspectives in the findings. We excluded studies exclusively recruiting high-risk populations defined as follows: (1) women with a history of breast cancer; (2) women with a family history of breast cancer; (3) women with a genetic predisposition for cancer. We also excluded studies that evaluated older women’s perceptions toward diagnostic or future mammography after receiving an abnormal mammogram.

Results

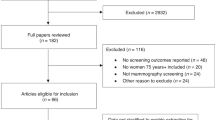

The database search yielded 4421 articles. After deleting 1356 duplicate articles, the titles and abstracts from 3065 articles were independently screened by two reviewers, followed by a full-text screen and reference list scan for 37 systematic reviews. One researcher extracted data from studies satisfying all inclusion/exclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

We identified 43 studies: 31 quantitative (24 observational, 7 intervention), 11 qualitative, and 1 mixed-method. The details of the extracted studies are presented in Table 1. The majority (86.4%) focused on mammography underuse, particularly among racially and/or ethnically diverse populations (70.5%). Only five studies exclusively recruited women aged ≥ 65 years [35••, 36••, 37••, 38•, 39•], of which four focused on perspectives toward mammography overuse [35••, 36••, 37••, 38•]. All findings are presented in a narrative format by key perspectives.

Knowledge of Mammography Screening

Over one third of the studies assessed or described older women’s knowledge of breast cancer and/or mammography screening, mainly to understand perspectives contributing to mammography underuse. Several studies found a significant positive association between knowledge and mammography behavior [42, 49, 52, 55, 66, 68]. Knowledge of guideline recommendations regarding the initiation and frequency of screening varied across studies; between 61% and 88% of women perceived they should receive a mammogram every 1 to 2 years [42, 52, 57•, 60•]. One study found that 67% of women felt confused about the frequency of screening following changes in USPSTF guidelines recommendations [41] and another study found that less than half of women were aware of updates to the USPSTF guidelines around the frequency of screening [60•].

Only two studies measured knowledge of mammography screening in the context of mammography overuse. In a study assessing women aged ≥ 75 years, knowledge around the harms and benefits of mammography screening found that women correctly identified an average of 6.3 out of 10 questions [78]. In a mixed-methods study with women ≥ 70 years, few women had heard about the concept of mammography overuse and less than half understood the meaning of overuse after being presented with hypothetical scenarios illustrating the potential harms and benefits of overuse [36••].

Perceived Susceptibility and Perceived Seriousness of Breast Cancer

Over half of the studies assessed or described women’s perceived susceptibility and perceived seriousness toward breast cancer related to mammography use or overuse. Perceived susceptibility was primarily operationalized as one’s perceived risk or chance of getting breast cancer while perceived seriousness was often defined as severity, worry, fear of a cancer diagnosis, or belief that cancer is a death sentence (fatalism). Terminology varied across studies with some studies operationalizing perceived susceptibility or seriousness as a barrier or facilitator to mammography screening.

Quantitative and qualitative studies suggest that older women perceive low susceptibility to breast cancer; between 43% and 72% of women perceived they had little to no chance of getting breast cancer [37••, 39•, 48•, 49, 51, 54, 56, 57•, 58, 59, 64, 65, 71, 75,76,77]. Two cross-sectional studies found that women ≥ 65 years reported lower levels of perceived susceptibility to breast cancer compared with women ≤ 65 years [48•, 57•]. Insights from qualitative studies suggest that women’s perceived level of susceptibility was shaped by age, the presence/absence of breast symptoms, family history, and understanding around the causes of breast cancer [39, 71, 75,76,77]. For instance, a woman between 65 and 75 years of age shared in an interview that she did not perceive herself to be at risk of breast cancer and would only get a mammogram if she felt like “there’s something that’s going on” [77]. In another qualitative study with women between 65 and 94 years, several described that one’s perceived susceptibility to breast cancer increased if there was a family history of breast cancer or by “hitting” or “squeezing” one’s breast [39•].

Despite relatively low levels of perceived susceptibility among older women, several studies support the notion that older women perceive breast cancer to be serious, are worried or fearful about getting breast cancer and undergoing treatment, and/or believe there is not much one can do to keep from getting cancer [39•, 42, 45, 48•, 56, 70, 71, 74, 76, 77]. The association between perceived seriousness and mammography screening behavior differed across studies likely due to variation in operationalization, measurement, and study populations. For instance, one cross-sectional study found that Korean-American women ≥ 65 years perceive breast cancer to be more serious compared to Korean-American women ≤ 65 years [48•] and a cross-sectional study of women ≥ 65 years from racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds found that women who are more worried about breast cancer were more likely to undergo screening [45]. In contrast, older Hopi women who feared a breast cancer diagnosis were less likely to undergo mammography screening [42] while a study among Dominican Latinas found no association between mammography behavior and the belief that there is not much one can do to keep from getting cancer or that cancer was a death sentence [40].

Perceived Barriers to Mammography Screening

Perceived barriers toward mammography screening were the most frequently examined perspective, particularly among studies focusing on underuse. While no study described perceived barriers to mammography overuse among women ≥ 65 years, one study found that women ≥ 65 years report fewer barriers to mammography screening compared with women ≤ 65 years [48•]. Embarrassment and pain related to getting a mammogram were among the most commonly reported barriers [39•, 42, 46, 47, 56, 69, 71, 73, 76]. Access barriers, such as cost/lack of insurance, lack of transportation, and difficulty making an appointment, were also commonly reported across quantitative and qualitative studies [42, 50, 52, 54, 63, 72, 74,75,76,77]. Additional barriers to mammography screening include concerns around radiation exposure, competing demands/time, and women not being aware of or told by their provider to get a mammogram [46, 47, 51, 52, 54, 56, 63, 71, 72, 74, 75, 77]. Overall, perceived barriers represented a consistent group of drivers of mammography screening behavior, with women reporting more barriers being less likely to receive a mammogram [40, 42, 43, 45, 48•, 53, 61, 62, 66].

Cultural and Religious Beliefs

A number of studies emphasized the role of cultural and religious beliefs in shaping attitudes and health beliefs toward mammography screening. Only one qualitative study explored the role of cultural and religious beliefs among women ≥ 65 years [39•] and no study explored the role of cultural or religious beliefs around mammography overuse. Language-related barriers to care, modesty concerns around exposing oneself to strangers, beliefs that talking about breast cancer will result in breast cancer, and not wanting to burden families were commonly reported as culturally specific barriers to mammography screening [49, 54, 72, 73, 75, 77]. Cultural and religious beliefs also shaped knowledge around the causes of breast cancer and perceptions around one’s risk of getting breast cancer [39•, 54, 63, 66]. For instance, a qualitative study of African-American women ≥ 65 years found that many perceived their health to be “in God’s hands” and although they feared breast cancer, they believed they needed to put their family’s needs before their own; these beliefs in turn impacted their mammography screening behavior [39•].

Attitudes and Benefits toward Mammography Screening

Nearly two thirds of studies describe attitudes and perceived benefits of screening. Older women generally held positive attitudes toward mammography screening and reported high levels of perceived benefits [43, 46, 48•, 50, 51, 56, 58, 59, 60•, 62, 65, 68, 70, 72, 74,75,76]. The desire for early detection and a personal responsibility to stay healthy emerged as the primary benefit of mammography screening [35••, 36, 39, 42, 50, 52, 56, 60, 70, 74, 76]. However, the extent to which perceived benefits and/or positive attitudes shape mammography use or overuse differed across studies. Specifically, a study with a nationally representative sample found no statistically significant direct or indirect pathway linking perceived benefits to mammography behavior [62] while a cross-sectional study considering women ≥ 65 years separately from younger women found higher levels of perceived benefits was associated with an increased likelihood of having a mammogram in the older age group [48•].

Among the five studies reporting data only on women ≥ 65 years, between 50 and 85% of older women intended intended) to continue mammography screening [35••, 36••, 37••, 38•, 39•, 43, 48•]. Data from a qualitative study with women ≥ 70 years who received a mammogram in the past 3 years found that positive attitudes and the habitual nature of mammography screening resulted in many resisting the idea of reducing or discontinuing screening, even when presented with a number of scenarios such as poor physical health, provider/expert recommendation to stop screening, lack of beneficial effects for life expectancy, and/or not receiving treatment [35••]. In a study testing the effects of a paper-based mammography screening decision aid for women ≥ 75 years on their screening decisions, over two thirds of women believed that their providers wanted them to have a mammogram at baseline [38•]. This finding is supported by other studies inclusive of women ≥ 65 years suggesting that a recommendation or reminder from their provider [36••, 50, 65, 72, 74,75,76] and/or a family or friend recommendation or encouragement [35••, 50, 62, 65, 72, 76] may facilitate mammography use.

Conclusions

This narrative review makes an important and timely contribution to the literature by examining older women’s perspectives around mammography screening in the USA. Overall, knowledge around guideline recommendations or the potential harms of screening is limited and older women continue to hold positive attitudes around mammography screening and believe that the benefits outweigh the barriers. Although perceived susceptibility to breast cancer varied, older women generally believe that breast cancer is serious and are worried about being diagnosed with breast cancer and undergoing treatment. These findings coupled with the belief that mammography screening is critical for the early detection of cancer may explain strong intentions to continue mammography screening in older women. These findings are generally consistent with prior research demonstrating widespread support for cancer screening among older adults in the USA and with studies performed outside of the USA [26,27,28,29].

Indicated by this review, research efforts to address mammography screening inequities continue to prioritize underuse among racial/ethnic minority groups. Consistent with published research, older racial/ethnic minority women experience a variety of attitudinal, personal, and structural barriers to screening mammography [14, 79, 80]. Mammography underuse among population groups experiencing inequities in late stage breast cancer and mortality risk remains an important priority area. However, efforts to address inequities in mammography access and use may inadvertently expose older women to the immediate harms of mammography screening that are disproportionate to the potential for long-term benefits [81]. More epidemiologic and interventional research using mixed-method approaches is needed to understand the scope of mammography overuse in racially and ethnically diverse populations that differ in their values, beliefs, experiences, and norms and to ensure that older racial and ethnic minority women are not inadvertently being targeted for more screening when the harms outweigh the benefits. This, in turn, can aid in developing strategies and interventions that are culturally and linguistically tailored to populations of interest [82,83,84].

This review highlights that perspectives driving screening mammography overuse among older women remains a critical yet understudied area [14, 85, 86]. Reducing or discontinuing the use of harmful, low-value care, referred to as de-implementation, is emerging as a key area of implementation science research [14, 85]. There is also growing recognition that approaches to de-implementation are likely distinct from implementation, meaning that we need research focused specifically on methods that promote de-implementation. Understanding perspectives driving mammography overuse at the patient level is a critical first step to successful de-implementation; however, screening mammography is often routine, automatic, obligatory, and not perceived as a decision. These attributes make de-implementation of mammography screening particularly challenging. As seen in this review, informing older women about the option to reduce the frequency of or discontinuing routine mammography screening may run counterintuitive to long-standing attitudes and beliefs, and may provoke confusion or skepticism [31, 32, 87, 88]. As a result, traditional patient-level approaches to educate and target cognitive processes to decision-making may prove insufficient. Although this review focuses and highlights the importance of considering patient-level perspectives in future efforts, changing women’s perspectives will need to involve strategies and approaches at the policy, health system, and provider levels. To this end, de-implementation efforts will need to consider multiple levels synergistically with a comprehensive patient-level component focused on addressing commonly held attitudes and beliefs that may be more resistant to change and more unconscious processes that occur in response to emotive cues derived from a previously learned behavior [89, 90].

This review set out to summarize older women’s perspectives toward mammography use and overuse following the updates to guidelines recommendations in the USA; yet, there are several limitations. Our search strategy identified peer-reviewed articles of studies that included older women ages ≥ 65; however, the vast majority of studies also included women in younger age groups, and thus our findings also represent perspectives of younger women. The focus of this review was also to provide a narrative synthesis and no formal evaluation of the quality of all empirical evidence was performed. The majority of studies included in this review used observational quantitative or qualitative study designs, and showed substantial variations in age distribution, operationalization and measurement of perspectives, and demographic characteristics, thereby limiting the generalizability of our findings and our ability to make meaningful comparisons across studies and populations. Future research efforts should give greater consideration to sample characteristics, notably age, given changes in guideline recommendations that increasingly consider age-relevant burden of potential harms, evidence on benefits, life expectancy, and comorbidities. This review includes seven intervention studies reporting baseline perspectives of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs toward mammography screening; however, interpreting baseline levels of perspectives was challenging due to insufficient reporting on the reliability, validity, and scoring of survey items. Thus, there is a need for more rigorous study designs, such as mixed-methods, and improved reporting and measurement of outcomes to identify the most salient factors and underlying processes explaining mammography use and overuse in older women.

Despite these limitations, this narrative review highlighted key gaps in our understanding of older women’s perspectives contributing to mammography overuse more broadly and among racially and ethnically diverse populations. Findings from the present study also help to distinguish differences in perspectives related to underuse and overuse, as well as differences in perspectives by race, ethnicity, and advancing age. Collectively, findings from this review emphasize the need for approaches, strategies, and messaging tailored to the values, attitudes, and beliefs of patients and aligns with calls to prioritize de-implementation of overuse of mammography screening in older adults.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. 2020;70(1):7–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21590.

Pace LE, Keating NL. A systematic assessment of benefits and risks to guide breast cancer screening decisions. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1327–35. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.1398.

Nyström L, Andersson I, Bjurstam N, Frisell J, Nordenskjöld B, Rutqvist LE. Long-term effects of mammography screening: updated overview of the Swedish randomised trials. Lancet (London, England). 2002;359(9310):909–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08020-0.

Howlader N NA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute2019.

Walter LC, Schonberg MA. Screening mammography in older women: a review. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1336–47. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.2834.

Demb J, Allen I, Braithwaite D. Utilization of screening mammography in older women according to comorbidity and age: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0345-y.

Braithwaite D, Mandelblatt JS, Kerlikowske K. To screen or not to screen older women for breast cancer: a conundrum. Future Oncol (London, England). 2013;9(6):763–6. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon.13.64.

Demb J, Akinyemiju T, Allen I, Onega T, Hiatt RA, Braithwaite D. Screening mammography use in older women according to health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:1987–97. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S171739.

Demb J, Abraham L, Miglioretti DL, Sprague BL, O'Meara ES, Advani S, et al. Screening mammography outcomes: risk of breast cancer and mortality by comorbidity score and age. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;112:599–606. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djz172.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–26. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008.

Screening for breast cancer: recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):I-28-I-. https://doi.org/10.7326/P16-9005 Annals of Internal Medicine.

Oeffinger KC, Fontham ETH, Etzioni R, Herzig A, Michaelson JS, Shih Y-CT et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.12783 JAMA.

Qaseem A, Lin JS, Mustafa RA, Horwitch CA, Wilt TJ. Physicians ftCGCotACo. Screening for breast cancer in average-risk women: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(8):547–60. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-2147 Annals of Internal Medicine.

Helfrich CD, Hartmann CW, Parikh TJ, Au DH. Promoting health equity through de-implementation research. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(Suppl 1):93–6. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.29.S1.93.

Elshaug AG, Rosenthal MB, Lavis JN, Brownlee S, Schmidt H, Nagpal S, et al. Levers for addressing medical underuse and overuse: achieving high-value health care. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390(10090):191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32586-7.

Extermann M. Measurement and impact of comorbidity in older cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;35(3):181–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00090-1.

Hubbard RA, Kerlikowske K, Flowers CI, Yankaskas BC, Zhu W, Miglioretti DL. Cumulative probability of false-positive recall or biopsy recommendation after 10 years of screening mammography: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):481–92. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00004.

Ernster VL, Ballard-Barbash R, Barlow WE, Zheng Y, Weaver DL, Cutter G, et al. Detection of ductal carcinoma in situ in women undergoing screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(20):1546–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/94.20.1546 JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Mandelblatt JS, Cronin KA, Bailey S, Berry DA, de Koning HJ, Draisma G, et al. Effects of mammography screening under different screening schedules: model estimates of potential benefits and harms. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):738–47. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00010.

Brodersen J, Siersma VD. Long-term psychosocial consequences of false-positive screening mammography. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(2):106–15. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1466.

van der Steeg AF, Keyzer-Dekker CM, De Vries J, Roukema JA. Effect of abnormal screening mammogram on quality of life. Br J Surg. 2011;98(4):537–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7371.

Løberg M, Lousdal ML, Bretthauer M, Kalager M. Benefits and harms of mammography screening. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17(1):63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-015-0525-z.

Myers ER, Moorman P, Gierisch JM, Havrilesky LJ, Grimm LJ, Ghate S, et al. Benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1615–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.13183 JAMA.

Braithwaite D, Demb J, Henderson LM. Optimal breast cancer screening strategies for older women: current perspectives. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:111–25. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.S65304.

Braithwaite D, Walter LC, Izano M, Kerlikowske K. Benefits and harms of screening mammography by comorbidity and age: a qualitative synthesis of observational studies and decision analyses. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):561–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3580-3.

Collins K, Winslow M, Reed MW, Walters SJ, Robinson T, Madan J, et al. The views of older women towards mammographic screening: a qualitative and quantitative study. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(10):1461–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605662.

Lewis CL, Couper MP, Levin CA, Pignone MP, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Plans to stop cancer screening tests among adults who recently considered screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):859–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1346-5.

Linsell L, Burgess CC, Ramirez AJ. Breast cancer awareness among older women. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(8):1221–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604668.

von Wagner C, Macedo A, Campbell C, Simon AE, Wardle J, Hammersley V, et al. Continuing cancer screening later in life: attitudes and intentions among older adults in England. Age Ageing. 2013;42(6):770–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft132.

Schonberg MA, McCarthy EP, York M, Davis RB, Marcantonio ER. Factors influencing elderly women’s mammography screening decisions: implications for counseling. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-7-26.

Schonberg MA, Ramanan RA, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER. Decision making and counseling around mammography screening for women aged 80 or older. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):979–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00487.x.

Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ Jr, Welch HG. Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291(1):71–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.1.71.

Seaman K, Dzidic PL, Castell E, Saunders C, Breen LJ. A systematic review of women’s knowledge of screening mammography. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2018;42:81–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2018.08.102.

Nelson HD, Pappas M, Cantor A, Griffin J, Daeges M, Humphrey L. Harms of breast cancer screening: systematic review to update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):256–67. https://doi.org/10.7326/m15-0970.

•• Housten AJ, Pappadis MR, Krishnan S, Weller SC, Giordano SH, Bevers TB, et al. Resistance to discontinuing breast cancer screening in older women: a qualitative study. Psycho-oncology. 2018;27(6):1635–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4708. Qualitative study examining the willingness of older women from diverse background to discontinue mammography screening. Found that older women over the age of 70 hold strong intentions to continue screening and are resistant to the idea of discontinuing screening.

•• Pappadis MR, Volk RJ, Krishnan S, Weller SC, Jaramillo E, Hoover DS, et al. Perceptions of overdetection of breast cancer among women 70 years of age and older in the USA: a mixed-methods analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e022138. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022138. A mixed-methods study with 59 English-speaking women over the age of 70 with no prior history of breast cancer exploring perceptions towards overdetection of breast cancer and its influence on future screening. Study found that many older women did not understand the concept of overdetection or were resistant to the concept.

•• Schonberg MA, Hamel MB, Davis RB, Griggs MC, Wee CC, Fagerlin A, et al. Development and evaluation of a decision aid on mammography screening for women 75 years and older. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):417–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13639. The purpose of this study was to develop and evaluate a mammography screening decision aid for women 75 years and older. Comparison of pre/post survey data found that knowledge of the harms and benefits of mammography screening significantly improved. Although decisional conflict declined, results were not significant. Findings suggest that a decision aid may improve older women's decision-making around mammography screening.

• Schonberg MA, Kistler CE, Pinheiro A, Jacobson AR, Aliberti GM, Karamourtopoulos M, et al. Effect of a mammography screening decision aid for women 75 years and older: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:831. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0440. This was a cluster-randomized control trial testing the effects of a paper-based mammography screening decisions aid for women 75 years and older. 546 women were assigned to an intervention or control group and matched. Findings show that providing older women with a decision aid before a primary care appointment facilitates informed decision-making and may help to reduce overscreening.

• Swinney JE, Dobal MT. Older African American women’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors about breast cancer. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2011;4(1):9–18. https://doi.org/10.3928/19404921-20101207-01. A qualitative study with 57 African American women over the age of 65 to identify factors associated with regular participation in mammography screening. Analysis of focus groups identified themes that can be used to inform the development of culturally relevant educational efforts to promote breast health practices.

Abraído-Lanza AF, Martins MC, Shelton RC, Flórez KR. Breast cancer screening among Dominican Latinas: a closer look at fatalism and other social and cultural factors. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(5):633–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198115580975.

Allen JD, Bluethmann SM, Sheets M, Opdyke KM, Gates-Ferris K, Hurlbert M, et al. Women’s responses to changes in U.S. Preventive Task Force’s mammography screening guidelines: results of focus groups with ethnically diverse women. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1169. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1169.

Brown SR, Nuno T, Joshweseoma L, Begay RC, Goodluck C, Harris RB. Impact of a community-based breast cancer screening program on Hopi women. Prev Med. 2011;52(5):390–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.02.012.

Cadet TJ. The relationship between psychosocial factors and breast cancer screening behaviors of older Hispanic women. Soc Work Public Health. 2015;30(2):207–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2014.969857.

Casciotti DM, Klassen AC. Factors associated with female provider preference among African American women, and implications for breast cancer screening. Health Care Women Int. 2011;32(7):581–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2011.565527.

Consedine NS. The demographic, system, and psychosocial origins of mammographic screening disparities: prediction of initiation versus maintenance screening among immigrant and non-immigrant women. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(4):570–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-011-9524-z.

Cumberland WG, Berman BA, Zazove P, Sadler GR, Jo A, Booth H, et al. A breast cancer education program for D/deaf women. Am Ann Deaf. 2018;163(2):90–115. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2018.0014.

Davis C, Cadet TJ, Moore M, Darby K. A comparison of compliance and noncompliance in breast cancer screening among African American women. Health Soc Work. 2017;42(3):159–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlx027.

• Eun Y, Lee EE, Kim MJ, Fogg L. Breast cancer screening beliefs among older Korean American women. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(9):40–50. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20090731-09. An observational study (n=187) describing health beliefs related to older Korean-American women’s screening behaviors, comparing them to beliefs of younger women. Older women over the age of 65 were significantly less likely to have ever had a mammogram, perceived themselves to be less susceptible to breast cancer, reported lower levels of perceived benefits, and higher levels of perceived seriousness and barriers compared to younger women.

Han H-R, Lee H, Kim MT, Kim KB. Tailored lay health worker intervention improves breast cancer screening outcomes in non-adherent Korean-American women. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(2):318–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyn021.

Harvey S, Gallagher AM, Nolan M, Hughes CM. Listening to women: expectations and experiences in breast imaging. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(9):777–83. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.29001.swh.

Huerta EE, Weeks-Coulthurst P, Williams C, Swain SM. Take care of your neighborhood. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;167(1):225–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4492-1.

Khaliq W, Visvanathan K, Landis R, Wright SM. Breast cancer screening preferences among hospitalized women. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(7):637–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2012.4083.

Lee HY, Stange MJ, Ahluwalia JS. Breast cancer screening behaviors among Korean American immigrant women: findings from the health belief model. J Transcult Nurs. 2015;26(5):450–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659614526457.

Lee-Lin F, Menon U, Leo MC, Pedhiwala N. Feasibility of a targeted breast health education intervention for Chinese American immigrant women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(4):361–72. https://doi.org/10.1188/13.Onf.361-372.

Lee-Lin F, Nguyen T, Pedhiwala N, Dieckmann N, Menon U. Mammography screening of Chinese immigrant women: ever screened versus never screened. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42(5):470–8. https://doi.org/10.1188/15.Onf.470-478.

Lopez ED, Khoury AJ, Dailey AB, Hall AG, Chisholm LR. Screening mammography: a cross-sectional study to compare characteristics of women aged 40 and older from the deep south who are current, overdue, and never screeners. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19(6):434–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2009.07.008.

• Madadi M, Zhang S, Yeary KH, Henderson LM. Analyzing factors associated with women’s attitudes and behaviors toward screening mammography using design-based logistic regression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(1):193–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-2850-9. A cross-sectional analysis using the 2003 Health Information National Trends Survey to examine factors associated with screening mammography adherence. Results show that as women age, they are less likely to think about getting a mammogram compared to women aged 43-49.

Medina-Shepherd R, Kleier JA. Spanish translation and adaptation of Victoria Champion’s health belief model scales for breast cancer screening—mammography. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(2):93–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c75d7b.

Medina R, Kleier J. Using the health belief model for predicting mammography screening behavior among Spanish-speaking Hispanic women of southeastern Florida. Hispanic Health Care Int. 2012;10:61–9. https://doi.org/10.1891/1540-4153.10.2.61.

• Mehta JM, MacLaughlin KL, Millstine DM, Faubion SS, Wallace MR, Shah AA, et al. Breast cancer screening: women’s attitudes and beliefs in light of updated United States Preventive Services Task Force and American Cancer Society guidelines. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(3):302–13. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2017.6885. A large cross-sectional study of 555 women presenting at Mayo Clinic to explore women’s attitudes regarding mammography and evaluating the impact of updated screening guidelines on these attitudes. The majority of women were unaware of recent guidelines changes and many planned to undergo annual screening.

Menon U, Szalacha LA, Prabhughate A. Breast and cervical cancer screening among south Asian immigrants in the United States. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(4):278–87. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822fcab4.

Murphy CC, Vernon SW, Diamond PM, Tiro JA. Competitive testing of health behavior theories: how do benefits, barriers, subjective norm, and intention influence mammography behavior? Ann Behav Med. 2014;47(1):120–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9528-0.

Nguyen-Truong CKY, Pedhiwala N, Nguyen V, Le C, Vy Le T, Lau C, et al. Feasibility of a multicomponent breast health education intervention for Vietnamese American immigrant women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(5):615–25. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.Onf.615-625.

O'Donnell S, Goldstein B, Dimatteo MR, Fox SA, John CR, Obrzut JE. Adherence to mammography and colorectal cancer screening in women 50–80 years of age the role of psychological distress. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(5):343–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2010.04.002.

Strong C, Liang W. Relationships between decisional balance and stage of adopting mammography and pap testing among Chinese American women. Cancer Epidemiol. 2009;33(5):374–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2009.10.002.

Wang JH, Mandelblatt JS, Liang W, Yi B, Ma IJ, Schwartz MD. Knowledge, cultural, and attitudinal barriers to mammography screening among nonadherent immigrant Chinese women: ever versus never screened status. Cancer. 2009;115(20):4828–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24517.

Wang JH, Schwartz MD, Luta G, Maxwell AE, Mandelblatt JS. Intervention tailoring for Chinese American women: comparing the effects of two videos on knowledge, attitudes and intentions to obtain a mammogram. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(3):523–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cys007.

Wu TY, Ronis D. Correlates of recent and regular mammography screening among Asian-American women. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(11):2434–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05112.x.

Engelman KK, Cizik AM, Ellerbeck EF, Rempusheski VF. Perceptions of the screening mammography experience by Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(4):e395–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2012.04.006.

Flórez KR, Aguirre AN, Viladrich A, Céspedes A, De La Cruz AA, Abraído-Lanza AF. Fatalism or destiny? A qualitative study and interpretative framework on Dominican women’s breast cancer beliefs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(4):291–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-008-9118-6.

Friedman AM, Hemler JR, Rossetti E, Clemow LP, Ferrante JM. Obese women’s barriers to mammography and pap smear: the possible role of personality. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2012;20(8):1611–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2012.50.

Lee-Lin F, Menon U, Nail L, Lutz KF. Findings from focus groups indicating what Chinese American immigrant women think about breast cancer and breast cancer screening. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41(5):627–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01348.x.

Lende DH, Lachiondo A. Embodiment and breast cancer among African American women. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(2):216–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732308328162.

Schoenberg NE, Kruger TM, Bardach S, Howell BM. Appalachian women’s perspectives on breast and cervical cancer screening. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13(3):2452.

Simon MA, Tom LS, Dong X. Breast cancer screening beliefs among older Chinese women in Chicago’s Chinatown. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2017;72(suppl_1):S32-s40. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw247.

Tejeda S, Thompson B, Coronado GD, Martin DP. Barriers and facilitators related to mammography use among lower educated Mexican women in the USA. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2009;68(5):832–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.023.

Watson-Johnson LC, DeGroff A, Steele CB, Revels M, Smith JL, Justen E, et al. Mammography adherence: a qualitative study. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(12):1887–94. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2724.

Schonberg MA, Hamel MB, Davis RB, Griggs MC, Wee CC, Fagerlin A, et al. Development and evaluation of a decision aid on mammography screening for women 75 years and older. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):417–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13639.

Kressin NR, Groeneveld PW. Race/ethnicity and overuse of care: a systematic review. Milbank Q. 2015;93(1):112–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12107.

• Miller BC, Bowers JM, Payne JB, Moyer A. Barriers to mammography screening among racial and ethnic minority women. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2019;239:112494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112494. A recent literature review exploring barriers to mammography screening among racial/ethnic minority women. Does not report differences in barriers by age. Study emphasizes the need for additional studies exploring cultural and sociodemographic barriers designed to allow for better comparison across studies.

Schpero WL, Morden NE, Sequist TD, Rosenthal MB, Gottlieb DJ, Colla CH. For selected services, blacks and Hispanics more likely to receive low-value care than whites. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1065–9. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1416.

Mead EL, Doorenbos AZ, Javid SH, Haozous EA, Alvord LA, Flum DR, et al. Shared decision-making for cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):e15–29. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301631.

Chenel V, Mortenson WB, Guay M, Jutai JW, Auger C. Cultural adaptation and validation of patient decision aids: a scoping review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:321–32. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S151833.

Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D, Sloan JA, Carriere KC, O'Neil J et al. Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA. 1997;277(18):1485–1492. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03540420081039 JAMA.

Norton WE, Chambers DA, Kramer BS. Conceptualizing de-implementation in cancer care delivery 2019;37(2):93–96. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.18.00589.

Norton WE, Chambers DA. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0960-9.

Hoffman RM, Lewis CL, Pignone MP, Couper MP, Barry MJ, Elmore JG, et al. Decision-making processes for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screening: the DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Mak. 2010;30(5 Suppl):53s–64s. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x10378701.

Torke AM, Schwartz PH, Holtz LR, Montz K, Sachs GA. Older adults and forgoing cancer screening: “I think it would be strange”. JAMA Int Med. 2013;173(7):526–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2903 JAMA Internal Medicine.

Norton WE, Chambers DA. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0960-9.

Helfrich CD, Rose AJ, Hartmann CW, van Bodegom-Vos L, Graham ID, Wood SJ, et al. How the dual process model of human cognition can inform efforts to de-implement ineffective and harmful clinical practices: a preliminary model of unlearning and substitution. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24(1):198–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12855.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Social Epidemiology

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Austin, J.D., Shelton, R.C., Lee Argov, E.J. et al. Older Women’s Perspectives Driving Mammography Screening Use and Overuse: a Narrative Review of Mixed-Methods Studies. Curr Epidemiol Rep 7, 274–289 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-020-00244-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-020-00244-3