Abstract

Purpose of Review

Although gaming disorder (GD) is prevalent during adolescence and group-based interventions (GBIs) prove highly beneficial for substance use disorders, much remains unknown regarding their utility for addressing problematic gaming (PG) and GD. This systematic review thus explores the potential value of GBIs for adolescents with PG/GD.

Recent Findings

With the inclusion of PG/GD as a potential diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association in 2013 and the acceptance of GD as a psychological disorder by the World Health Organization in 2019, research on this topic has proliferated. Although reviews to date have accorded attention to cognitive behavioral therapy, technology-based interventions, or focused on broader conditions such as “Internet addiction,” none has exclusively focused on GBIs or adolescent populations.

Summary

The findings from the eight retained studies suggest a positive impact of GBIs on adolescent PG/GD. Nonetheless, the particular benefits of “the group” as a modality remained largely unaddressed. Future research should adopt more rigorous designs to understand its underlying mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prior to and after the formal acceptance by the World Health Organization of gaming disorder (GD) as a diagnosable clinical entity [1], practitioners and researchers developed and implemented psychological treatments to address gaming-related harms. GD is characterized by a pattern of persistent or recurrent (online or offline) gaming behavior, manifested by impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other life interests and daily activities, and the continuation or escalation of gaming despite negative consequences [2,3,4,5]. GD appears to be most prevalent among adolescents and young adult males between 12 and 20 years old, thus posing a risk for academic underachievement, school failure/dropout, and psychosocial and sleep problems [3,4,5,6]. This higher prevalence in adolescent populations necessitates a targeted approach to GD and problematic gaming (PG) behaviors (reflected by high amounts of time spent gaming or gaming motives that predict the development of GD, but presently do not rise to the level of GD [7,8,9]). Yet, little is known about effective interventions for adolescent populations and the underlying dynamics at work. As Stevens et al. [10] asserted: “It is necessary to determine which treatments are most effective for whom and under which conditions” [p. 191]. Furthermore, to maintain the effects of treatment over time, standard programs of therapy (which include elements of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and individual and family treatment approaches [10,11,12,13]) should be enhanced with “additional support” [11 p. 201]. One such form of support may be group-based interventions (GBIs) that can be part of indicated prevention measures, early intervention, or treatment.

Reports from clinical practice and research demonstrate the particular benefits of GBIs when treating adolescents [14, 15•, 16]. GBIs are typically delivered to small groups (5 to 10 people) by one or more practitioners and are used for mental health recovery, behavior change, and other aims [17•]. GBIs are the most commonly used treatment modality for adolescents with substance use disorders [16]. Given that adolescent GD shares etiological and phenomenological characteristics with adolescent substance use disorder, GBIs have untapped potential for addressing GD/PG [18].

The potential benefits of GBIs for behavior change include creating a conducive space for sharing by decreasing isolation, as well as for identification with and learning from other group members who experience similar problems [17•]. Notwithstanding these benefits, some potential challenges in delivering group interventions lie in “deviancy training,” “the process of contingent positive reactions to rule-breaking discussions” [20 p. 756]. Similarly, sustain talk (statements against change) by some of the group members can have an iatrogenic effect on peers when the facilitator does not address the ambivalence that they may have concerning their gaming behavior [19]. Therefore, “the group could spiral into a discussion about the benefits” of gaming, leading to decreased intentions toward change [21 p. 76]. Adolescents may vary in their gaming behavior severity and readiness for change, thus requiring skillful facilitation to prevent iatrogenic effects. Moreover, and of importance, much remains unknown concerning the potential benefits of GBIs for adolescents with GD/PG.

Against this backdrop, the objectives of this systematic review were to address the challenges and opportunities inherent in group-based treatment for adolescents with GD/PG and to delineate future clinical research and implementation directions. Our main focus was to determine the effectiveness of GBIs in terms of symptom reduction, motivational enhancement, and other indicators, as well as to explore in which combination with other interventions GBIs are used. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to explore the value of GBIs for adolescents with GD/PG.

Methods

This systematic review of the literature was performed following PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [20]. The protocol was also registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, CRD42023399423). From the conceptualization of the search strings to the synthesis of results, the process was performed by two authors (H.B. and D.L.S.) in close consultation with the co-authors. We consulted four academic databases (Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and ProQuest) to identify relevant studies. For each database, we combined search algorithms for the following concepts: (1) GD/PG, (2) group treatment, and (3) adolescence. The full algorithms per database are available in Appendix 1. The final search was conducted on the 21st of February 2023. Following peer review, the search was repeated on the 7th of February 2024 for articles published between February 2023 and January 2024. The search strategy was informed by comparable review articles [11, 12, 21], three relevant studies known to the authors [22, 23, 24•], and consultation with an academic librarian. For searches in PubMed, MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms were retrieved and added to the search string. The search strategies were validated by testing whether they could identify the three known studies, which was the case in all four databases.

Published peer-reviewed articles were retained for consideration depending on whether they corresponded to the following population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and study design (PICOS) criteria [25]: (P) focusing on an adolescent target group (aged 12–18 years), (I) applying a group treatment approach (involving a minimum of five participants), (C) use of a comparison condition, (O) analyzing impact on GD/PG, and (S) application of an intervention study design. Articles predating the year 2000 were omitted because they would exclude online gaming. Only English-language studies were retained. We also only included studies that explicitly stated that individuals with GD were part of the sample. Given the focus on reducing the impact of gaming behavior in persons with mild to severe GD symptoms, we excluded universal prevention programs and included indicated prevention/early intervention strategies if all other criteria were met. Only quantitative study designs were eligible, provided they centered on interventions and were not theoretical or prevalence studies.

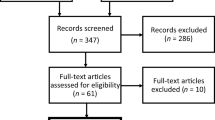

The initial search yielded 2946 results (1174 in Scopus, 794 in ProQuest, 530 in Web of Science, and 448 in PubMed). These results were processed according to the PRISMA guideline steps depicted in Fig. 1 and with the assistance of rayyan.ai software. The initial removal of duplicates led to the retention of 1308 articles to be screened by their title and abstracts. Twenty-three articles were found to match the search criteria, and their full texts were subsequently retrieved. One full-text article written in German could not be retrieved [26]. From the remaining retrieved articles, five were excluded due to language (French [27]; German [28, 29]) and publication type [30, 31].

As a result, 17 articles were found to match the search criteria and were subjected to a synchronous dual full-text reading and discussion to appraise their overall relevance to our research question. When the two authors involved in the review were not certain about the inclusion of a specific paper, a third author (W.V.) was consulted. This step led to the further deletion of ten articles: six did not focus on GD/PG severity as an outcome indicator [32,33,34,35,36,37]; two did not focus on adolescents [38, 39]; one consisted of a one-shot school-based intervention of 90 min, which could not be classified as being an indicated prevention [40]; and one involved a study design that did not introduce a group-based approach other than recreational school exercise [41]. Lastly, the reference lists of the retained articles were scrutinized to identify other potentially relevant studies. No additional articles were included after reference mining. Hence, seven papers were included in the current systematic literature review. The second round of database searches led to the inclusion of another study (see Appendix 2).

The following data were systematically extracted from the included studies: (a) names of the authors, year of publication, and country where the intervention was implemented, (b) characteristics of the sample (sample size, age, gender ratio) and description of the intervention setting, (c) description of the GBI (aim and conceptualization), (d) description of complementary interventions to the group intervention (if any), (e) underlying theoretical framework for the intervention, (f) measures used in the study (e.g., questionnaires, observations, and interviews) and conceptualization of GD/PG (diagnostic criteria used for GD), and (g) study results reported (outcomes measured). An assessment of each study’s methodological quality was also conducted by using the Quality Assessment with Diverse Studies (QuADS) appraisal tool [42].

Results

Table 1 presents a summary of the key characteristics of the seven included studies.

Included Studies on GBIs for Adolescents with GD/PG

Our search yielded eight articles on GBIs for adolescents with GD/PG that were conducted in Europe (Ukraine [43], Germany [24•, 44]) and Asia (China [51], Thailand [22], Iran [46], the Philippines [48], and Japan [23]). As a reflection of the rise in studies on interventions for GD/PG in recent years, all included articles were published in the last 7 years (2017–2023). Treatment settings varied from schools [44, 46, 51] to outpatient clinics [24•, 43, 48] and residential treatment facilities [22, 23].

Aim

None of the included studies sought abstinence from gaming. Rather, they aimed at controlled use [24•], healthy gaming [22], reducing symptom severity [43, 44, 46, 48, 51], improved psychological well-being [48, 51], reduction in time spent gaming [23, 51], and gaming motivation [51].

Description of the GBIs

GBIs were only one part of the program in four publications, alongside complementary approaches such as family group therapy [43], parental skill training/psychoeducation [22, 43, 46], or individual treatment sessions [23, 43].

Group size varied between 3Footnote 1 and 32 participants, and four studies [23, 24•, 43, 44] were conceptualized according to standard group psychotherapy sizes (5–10 persons [17•]). Two of the GBIs were offered within a residential treatment setting [22, 23]. Aside from these, sessions varied in terms of both number (between 4 and 10 sessions) and duration (between 90 min and 3 h). Interventions were delivered by clinical psychologists, student mentors, trained mental health professionals, and medical doctors. All interventions focused on emotional or behavioral change via cognitive restructuring (i.e., CBT). There was a difference in how this was approached, as some interventions were limited to psychoeducation [e.g., 46, 49]. Two interventions included experiential activities such as hiking, woodwork, sports, and cooking [22, 23]. One intervention [51] added a motivational component to the CBT protocol, fostering the discovery and use of participants’ strengths in real-life activities. The content of the interventions centered on sharing and confronting one’s own beliefs [e.g., 45, 47], functional emotional regulation skills training [e.g., 26], and the detrimental effects of excessive gaming on everyday life [e.g., 48].

In terms of measures, some studies assessed the construct of “Internet addiction” more broadly by using self-designed measures (e.g., test questionnaire to detect cyber-addiction [43]) or existing scales (Griffith’s [50] Six Components Model [23]; Meerkerk et al.’s [45] Compulsive Internet Use Scale [24•, 44]). Lemmens’ Game Addiction Scale was used in three of the included studies as a self-rating scale [24•, 44, 46] and also modified to a parental scale [24•, 44]. Another study [22] made use of a self-designed test (Game Addiction Screening Test [53]), which was administered only by proxy. Other instruments used were the nine-item Internet Gaming Disorder Scale ([48, 49]) and the Chen Internet Addiction Scale-Gaming version (CIAS-G; 55). Despite the time frame of this review, none of the measures of GD is based on the ICD-11 criteria [1].

All included studies relied on CBT as the therapeutic framework for the intervention (e.g., rational emotive behavior therapy [43]; Theory of Planned Behavior [46], and integrated cognitive behavioral therapy (ICBT) [51]). Although the group approach was mainly based on CBT, several studies offered complementary interventions consisting of an integration of mindfulness [48], (systemic) family therapy [43], communication theory [22, 43], parent management training [22, 46], and adventure therapy [22, 23]. These aforementioned studies were based on the therapeutic residential camp (TRC) model, which comprises 12 days of camp-style residence [35].

Outcomes on GD/PG Severity

All studies sought to decrease GD/PG symptoms and reported successfully achieving this goal to varying degrees. It is worth noting that studies differed in their conceptualization of GD/PG as reflected in their terminology, which we have used here to retain their meaning. In the following text, studies are referred to as study 1, study 2, and so forth, based on their order of appearance in the data extraction table (Table 1).

In the first study [43], in which “closed Group Psycho-correction Sessions with ‘Addicts’” focused on “game addiction” as one form of cyber-addiction, participants (n = 131 adolescents) reported a general reduction in the degree of gaming addiction between baseline and immediate follow-up assessments. Severe gaming addiction was reduced by 27%, whereas mild gaming addiction increased by 18% (i.e., those with a formerly severe addiction reported lower severity). An average of 8% of participants showed no signs of gaming addiction at follow-up.

In study 2 [44], a sample of 167 school-going adolescents who presented with high or moderate risk for GD were included in the PROTECT program, an indicated preventive group intervention. A greater reduction in symptom severity of GD or unspecified Internet use disorder was shown in comparison with that in the control group (n = 255), thus reflecting a 12.1% greater reduction of symptoms (baseline vs. 12-month follow-up). The effect size increased over time, and an initial increase in symptom severity (or problem awareness) at post-test was detected. There was no reported difference between the experimental and control groups regarding the incidence rate (six participants in each group developed GD in the 12-month follow-up period).

For study 3 [24•], PROTECT + targeted a sample of 54 participants who sought treatment for “excessive gaming” or Internet use, leading to a significant reduction in self-reported and parent-reported symptom severity after 12 months. The beneficial effect was found to be larger in more impaired individuals according to exploratory growth models. No significant change was observed at the 4-month follow-up measurement. According to the semi-structured retrospective interviews at 12-month follow-up, 38.9% (n = 14) of the participants decreased in severity from “high-risk” or “pathological game users” to “unproblematic users.”

In study 4 [22], parental appraisal of PG severity showed enduring (6 + months) improvement in all groups (group treatment, parental group treatment, and a combined approach), when compared with that for the wait-list control group who received a 1-h psychoeducation course. There was no significant difference in the effect size between the Parent Management Training for Game Addiction (PMT-G) and partaking in the Siriraj Therapeutic Residential Camp (S-TRC). The PMT-G emerged as the preferred option for treatment.

Study 5 [46] showed a higher mean reduction in pre- and post-intervention “game dependency” scores in the intervention group (educational intervention) when compared with that in the control group. This effect was not observed at the 3-month follow-up. The study also lends support to the Theory of Planned Behavior, which focuses on “knowledge, attitude and perceived behavioral control and behavioral intention” [48 p. 186] as important factors for behavioral change through an educational program.

As part of study 6 [48], the pre- and post-tests in the Acceptance and Cognitive Restructuring Intervention Program experimental group (N = 20) showed a significant decrease in levels of “Internet gaming disorder” and a rise in psychological well-being compared with that in the control group (N = 20).

In study 7 [23], a significant decrease in the median hours of gaming per day and per week was reported at the 3-month follow-up after a “Self-Discovery Camp.” In the post-intervention measurement of treatment readiness, a significant change was found only in the factor “taking steps,” pertaining to self-efficacy.

Lastly, in study 8 [51], by decreasing gaming motivation and maladaptive gaming cognitions, the ICBT intervention significantly reduced GD symptoms, time spent on gaming, and depression and anxiety symptoms. The treatment effect was maintained for 6 months.

Quality Assessment

Table 2 presents a summary of the QuADS [42] evaluation of the eight included studies. Given the small pool of eligible studies, we included non-randomized controlled trials, which precluded the use of the CONSORT criteria. Therefore, the QuADS were more suitable to assess and compare the quality of the selected studies with different methodologies. This tool, however, is not intended to distinguish between high- and low-quality studies [42]. The QuADS comprises a 13-item checklist scored on a 4-point scale that follows a scoring guide. The evaluation was performed by two authors (H.B. and D.L.S.). There was considerable variation in the quality of the included studies.

Two studies from the PROTECT group [24•, 44] stood out for their quality. A shortcoming found in the quality appraisal was, however, that both studies made only a general reference to broad theories that framed the interventions (CBT), rather than specifying how it was operationalized.

Impact on Motivation

Studies rarely reported on building motivation for change, even when participants were identified as being poorly motivated to participate in the intervention [22, 24•]. In the case of the most recent study [51], however, there was a focus on the interaction between cognition and motivation for gaming leading to a shift in time used to fulfill psychological needs.

Parental Guidance

Certain of the studied interventions targeted only adolescent gamers [23, 24•, 44, 48]. Study 1 [43] included family therapy with psychoeducation activities for parents, as well as a six-session group meeting on social and communicative training for adolescents and their parents. Study 4 [22] introduced a group intervention and an 8-week parental management training group, which were both studied in a standalone and combined format. In study 5 [46], a workshop on parents’ supervisory role was conducted, aiming for a higher level of parental monitoring of children’s gaming behavior.

Experiential Learning

Five studies focused on cognitive restructuring and did not mention the effect of experiential learning as a specific aspect of the group treatment [24•, 43, 44, 46, 48, 51]. The studies on residential interventions (both TRCs) facilitated experiential learning: workshops in which computer skills were introduced to be used more productively [22, 23], outdoor activities [22, 23], and family activities [22].

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize the available evidence on GBIs for adolescents with GD/PG. Eight articles from Europe and Asia were retained.

Studies primarily sought to reduce the impact of gaming on everyday life and help participants regain control over gaming behavior. In half of the studies, group sessions were only part of a larger treatment plan. All interventions studied focused on cognitive restructuring via CBT-based group approaches in different forms (e.g., psychoeducation, sharing and confronting beliefs, emotional regulation training, and planning leisure time). Only two studies implemented experiential learning [22, 23]. Regarding symptoms of GD, all studies reported decreases to varying degrees.

Collectively, the studies suggest that CBT-focused groups are the preferred orientation of clinicians and researchers in this area. However, the use of the group approach per se was never the primary focus of the studies, nor was there any reflection on group dynamics or the effects of the group on gaming behavior. Frameworks such as the Mechanisms of Action in Group-based Interventions (MAGI [54]) have emerged to address this need, describing six clusters of interacting factors: “(1) group intervention design features, (2) facilitation techniques, (3) group dynamic and development processes, (4) inter-personal change processes, (5) selective intra-personal change processes operating in groups, and (6) contextual influences” [56 p. 227]. The framework is intended to enhance the design and delivery of GBIs, as well as to direct further research, training, and evaluation thereof. The role of peer support in recovery was also not addressed in the interventions. From the self-help literature, it has been shown that engagement in group meetings fosters continuous abstinence and leads to recovery-supportive benefits (e.g., connectedness and acceptance) [55,56,57].

We observed that, consistent with earlier research on treatments for gaming-related issues among adults and adolescents [10, 11, 18, 58], our sample of studies lacks sufficient methodological robustness. In addition, as highlighted in Zajac and colleagues’ review [18], all of our included studies must be considered pilot studies, as they do not meet the criteria for well-established or probably efficacious treatment [59]. Methodological issues thus make it difficult to infer the role of the group approach in the results. That notwithstanding, CBT remains the most widely examined approach for adolescent groups. Given the call for innovative and complementary interventions by Stevens et al. [10], it is important to further develop and test new approaches to prevent and/or reduce PG/GD.

Clinical Relevance of the Findings

There is a growing need for research on PG/GD among adolescents and the use of GBIs. However, the study of adolescent GBIs might be more challenging than research on adult populations and/or individual interventions because of (1) the dynamics involved in the age group and the developmental stage of participants and (2) the additional practical challenges to group interventions in research trials [17•, 60, 61]. It is a challenging task to convene homogenous groups (e.g., in terms of severity of the disorder and motivation for change) of suitable size, which may impede the continuity of interventions and lead to dropout [17•, 49, 61]. In addition, to tease out group-induced effects, multiple other factors that may be implicated in intervention outcomes must be considered [62]. We echo Liddle’s [62] view that researchers are called upon to be “clinically creative.” Possible strategies include the use of post-session questionnaires [63] and in-depth interviews [14], as well as participatory observation [64], to help establish what actions in the group appear to have a positive or negative impact on the therapeutic process.

Dedicating more funding to this area of study may (1) further promote more methodologically robust research, (2) support participant recruitment and promote retention, and (3) foster clinician-researcher cooperation from the planning and designing of interventions.

Limitations

Our findings should be considered in light of some limitations. First, including only English-language studies restricted the scope of the review and excluded the proliferation of gaming-related studies published in German, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean [11]. Second, the exclusion of studies on “Internet addiction” may also have narrowed the scope of interventions that targeted gaming indirectly, as well as potentially relevant GBIs. As several studies were not restricted to GD, it is a limitation that outcomes could not exclusively be reported for GD. However, excluding these studies would have resulted in the loss of valuable information given the low number of studies overall. Third, the fact that studies varied in their operationalization of groups (size, composition, and setting) and intervention intensity (e.g., program duration and number of sessions) affected direct comparison. Fourth, although the QuADS is beneficial for assessing the quality of mixed methods studies, it emphasizes selected aspects of studies, remains descriptive, and focuses on replicability.

Suggestions for Further Research

We recommend that future research integrate observation and in-depth interviews when evaluating the outcomes of interventions on GD/PG. Over and above its utility as a design tool, the MAGI framework [54] could potentially guide the quality assessment of intervention protocols and studies. Furthermore, there is a need for research into how the natural psychological development of adolescents can be accounted for when examining the long- and short-term effects of treatment.

Conclusion

The value of GBIs did not come to the fore in the existing literature, and the power of “the group” and how it could be leveraged for the benefit of adolescents remained largely unaddressed. We are still in the early stages of treating persons with PG/GD, and the evidence base for GBIs is currently limited. CBT has been the framework of choice for GBIs for adolescents, and, although results are positive, studies are still in the pilot phase. In one study, parental training yielded similar results to those of the GBI for gamers, which suggests that working with parents to manage adolescent gamers could be more time and resource-efficient. Future studies should aim for innovative designs, where cooperation between researchers and clinicians is central to developing protocols for treatment and research that explicitly target adolescents and their families, and seek to overcome recurrent study limitations.

Data Availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this article and supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Notes

The PROTECT + study [24•] included 11 groups with sizes varying from three to seven participants. A group size of three is too small for our inclusion criteria, but this study used multiple groups.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

World Health Organization. 2023. ICD-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%253a%252f%252fid.who.int%252ficd%252fentity%252f1448597234. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Reed GM, First MB, Billieux J, Cloitre M, Briken P, Achab S, et al. Emerging experience with selected new categories in the ICD-11: complex PTSD, prolonged grief disorder, gaming disorder, and compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. World Psychiatry. 2022;21:189–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20960.

Stevens MW, Dorstyn D, Delfabbro PH, King DL. Global prevalence of gaming disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021;55:553–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420962851.

Gao Y-X, Wang J-Y, Dong G-H. The prevalence and possible risk factors of internet gaming disorder among adolescents and young adults: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;154:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.06.049.

Nogueira-López A, Rial-Boubeta A, Guadix-García I, Villanueva-Blasco VJ, Billieux J. Prevalence of problematic Internet use and problematic gaming in Spanish adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2023;326:115317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115317.

Király O, Koncz P, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z. Gaming disorder: a summary of its characteristics and aetiology. Compr Psychiatry. 2023;122:152376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2023.152376.

Király O, Billieux J, King DL, Urbán R, Koncz P, Polgár E, et al. A comprehensive model to understand and assess the motivational background of video game use: the gaming motivation inventory (GMI). J Behav Addict. 2022;11:796–819. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2022.00048.

Bäcklund C, Elbe P, Gavelin HM, Sörman DE, Ljungberg JK. Gaming motivations and gaming disorder symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Addict. 2022;11:667–88. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2022.00053.

Wang L, Li J, Chen Y, Chai X, Zhang Y, Wang Z, et al. Gaming motivation and negative psychosocial outcomes in male adolescents: an individual-centered 1-year longitudinal study. Front Psychol. 2021;12:743273. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.743273.

Stevens MW, King DL, Dorstyn D, Delfabbro PH. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for internet gaming disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2019;26:191–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2341.

King DL, Delfabbro PH, Wu AMS, Doh YY, Kuss DJ, Pallesen SP, et al. Treatment of internet gaming disorder: an international systematic review and CONSORT evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;54:123–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.002.

King D, Delfabbro P, Griffiths M, Gradisar M. Assessing clinical trials of Internet addiction treatment: a systematic review and CONSORT evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:1110–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.009.

Kuss DJ, Lopez-Fernandez O. Internet addiction and problematic Internet use: a systematic review of clinical research. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6:143–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.143.

Pingitore F, Ferszt GG. The “voice” and perspectives of adolescents participating in a short-term psychotherapy group. Int J Group Psychother. 2017;67:360–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207284.2016.1260460.

• Zajac K, Ginley M, Chang R. Treatments of internet gaming disorder: a systematic review of the evidence. Expert Rev Neurother. 2020;20:85–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2020.1671824. Provides a review of various types of treatment approaches for GD for adolescents and adults.

Kaminer Y. Challenges and opportunities of group therapy for adolescent substance abuse: s critical review. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1765–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.002.

• Biggs K, Hind D, Gossage-Worrall R, Sprange K, White D, Wright J, et al. Challenges in the design, planning and implementation of trials evaluating group interventions. Trials. 2020;21:116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3807-4. Proposes a holistic framework to address challenges in evaluating GBIs.

Zajac K, Ginley MK, Chang R, Petry NM. Treatments for internet gaming disorder and internet addiction: a systematic review. Psychol Addict Behav. 2017;31:979–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000315.

D’Amico EJ, Houck JM, Hunter SB, Miles JNV, Osilla KC, Ewing BA. Group motivational interviewing for adolescents: change talk and alcohol and marijuana outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83:68–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038155.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Costa S, Kuss DJ. Current diagnostic procedures and interventions for gaming disorders: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2019;10:578. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00578.

Pornnoppadol C, Ratta-apha W, Chanpen S, Wattananond S, Dumrongrungruang N, Thongchoi K, et al. A comparative study of psychosocial interventions for internet gaming disorder among adolescents aged 13–17 years. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020;18:932–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9995-4.

Sakuma H, Mihara S, Nakayama H, Miura K, Kitayuguchi T, Maezono M, et al. Treatment with the Self-Discovery Camp (SDiC) improves internet gaming disorder. Addict Behav. 2017;64:357–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.06.013.

• Szasz-Janocha C, Vonderlin E, Lindenberg K. Treatment outcomes of a CBT-based group intervention for adolescents with Internet use disorders. J Behav Addict. 2020;9:978–89. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00089. Very methodologically robust study on GBIs for GD/PG.

Stern C, Jordan Z, McArthur A. Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. Am J Nurs. 2014;114:53–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000445689.67800.86.

Dreier M, Beutel ME, Müller KW, Wölfling K. Pre-clinical approaches for gaming disorder and internet addiction: school-based prevention, media training and limitation of in-game-purchases (MIRPPU) [Prä-klinische ansätze der computerspiel- und internetsucht: schulbasierte präventionsansätze, medientraining und eine empfehlung für finanzielle obergrenzen bei in-game-käufen (MIRPPU)]. Suchttherapie. 2019;20:203–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1022-2874.

Rocher B, Caillon J, Bonnet S, Lagadec M, Leboucher J, Vénisse J-L, et al. Treatment groups in video game addiction [Les prises en charge de groupe dans l’addiction aux jeux video]. Psychotropes. 2013;18:109–22. https://doi.org/10.3917/psyt.183.0109.

Moll B, Thomasius R, Thomsen M, Wartberg L. Pilot study on the effectiveness of a cognitive behavioural group programme for adolescents with pathological internet use [Pilotstudie zur effektivität eines kognitiv-verhaltenstherapeutischen gruppenprogramms mit psychoedukativen anteilen für jugendliche mit pathologischem internetgebrauch]. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr. 2014;63:21–35. https://doi.org/10.13109/prkk.2014.63.1.21.

Szász-Janocha C, Vonderlin E, Lindenberg K. Die Wirksamkeit eines Frühinterventionsprogramms für Jugendliche mit Computerspiel-und Internetabhängigkeit: Mittelfristige Effekte der PROTECT+ Studie. Zeitschrift für Kinder-und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1024/1422-4917/a000673.

Szasz-Janocha C, Vonderlin E, Lindenberg K, Szasz-Janocha C, Vonderlin E, Lindenberg K. Analysis of a cognitive behavioral group therapy program for adolescents with Internet gaming and Internet use disorder: first results of an effectiveness study. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:149–149.

Szasz-Janocha C, Vonderlin E, Lindenberg K, Szasz-Janocha C, Vonderlin E, Lindenberg K. A cognitive behavioral group therapy program for adolescents with Internet gaming and Internet use disorder: effects at 12-months follow-up. J Behav Addict. 2019;8:35–35.

Ke G, Wong S. Outcome of the psychological intervention program: internet use for youth. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther. 2018;36:187–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-017-0281-3.

Nurmagandi B, Hamid AYS, Panjaitan RU. The influence of health education and group therapy on adolescent online gamers’ self-concepts. European J Mental Health. 2022;17:37–46. https://doi.org/10.5708/ejmh/17.2022.1.4.

Vieira JAJ, De Lima LRA, Silva DAS, Petroski EL. Effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention on the screen time of Brazilian adolescents: non-randomized controlled study. Motriz. 2018;24:3. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1980-657420180003e0046-18.

Koo C, Wati Y, Lee CC, Oh HY. Internet-addicted kids and South Korean government efforts: boot-camp case. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:391–4. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0331.

Mathew P, Krishnan R, Bhaskar R. Effectiveness of a nurse-led intervention for adolescents with problematic internet use. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2020;58:16–26. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20200506-03.

Sim T, Choo H, Low-Lim A, Lau J, Sim T, Choo H, et al. Adolscents’ and parents’ perspectives: a gaming disorder intervention in Singapore. Fam Relat. 2021;70:90–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12474.

Thana-Ariyapaisan P, Pornnoppadol C, Apinuntavech S, Seree P. Effectiveness of an intervention program to develop and enhance protective skills against game addiction among 4th through 6th grade students. J Med Assoc Thai. 2018;101(1):S13–8.

Walther B, Hanewinkel R, Morgenstern M. Effects of a brief school-based media literacy intervention on digital media use in adolescents: cluster randomized controlled trial. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17:616–23. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0173.

Bonnaire C, Serehen Z, Phan O. Effects of a prevention intervention concerning screens, and video games in middle-school students: influences on beliefs and use. J Behav Addict. 2019;8:537–53. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.54.

Mumcu HE, Yazici OF, Yilmaz O. Effect of 12-week recreational activity program on digital game addiction and peer relationships qualities in children. Acta Med Mediterr. 2021;37:2921–7.

Harrison R, Jones B, Gardner P, Lawton R. Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): an appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed- or multi-method studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06122-y.

Asieieva Y, Morvaniuk H, Voznyi D, Chetveryk-Burchak A, Storozh V. Efficiency of the complex program of psychocorrection of cyber-addictions among middle and late adolescents. Amazonia Investiga. 2022;11:38–47. https://doi.org/10.34069/ai/2022.56.08.4.

Lindenberg K, Kindt S, Szasz-Janocha C, Lindenberg K, Kindt S, Szasz-Janocha C. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy-based intervention in preventing gaming disorder and unspecified internet use disorder in adolescents: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2148995. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48995.

Meerkerk G-J, Van Den Eijnden RJJM, Vermulst AA, Garretsen HFL. The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0181.

Zamanian H, Sharifzadeh G, Moodi M. The effect of planned behavior theory-based education on computer game dependence in high school male students. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:186. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_18_20.

Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Development and validation of a game addiction scale for adolescents. Media Psychol. 2009;12:77–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260802669458.

Kochuchakkalackal Kuriala G, Reyes MES. Efficacy of the acceptance and cognitive restructuring intervention program (ACRIP) on the Internet gaming disorder symptoms of selected Asian adolescents. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;5:238–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00132-z.

Pontes HM, Griffiths MD. Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Comput Human Behav. 2015;45:137–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.006.

Griffiths MD. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Use. 2005;191–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359.

Ji Y, Wong DF. Effectiveness of an integrated motivational cognitive–behavioral group intervention for adolescents with gaming disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2023;118(11):2093–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16292.

Chen S-H, Weng L-J, Su Y-J, Wu H-M, Yang P-F. Development of a Chinese internet addiction scale and its psychometric study. Chinese J Psychol. 2003;45:279–94.

Pornnoppadol C, Sornpaisarn B, Khamklieng K, Pattana-amorn S. The development of Game Addiction Screening Test (GAST). J Psychiatr Assoc Thai. 2014;59:3–14.

Borek AJ, Abraham C, Greaves CJ, Gillison F, Tarrant M, Morgan-Trimmer S, et al. Identifying change processes in group-based health behaviour-change interventions: development of the mechanisms of action in group-based interventions (MAGI) framework. Health Psychol Rev. 2019;13:227–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1625282.

DeLucia C, Bergman BG, Formoso D, Weinberg LB. Recovery in narcotics anonymous from the perspectives of long-term members: a qualitative study. J Groups Addict Recover. 2015;10:3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1556035x.2014.969064.

Dekkers A, De Ruysscher C, Vanderplasschen W. Perspectives on addiction recovery: focus groups with individuals in recovery and family members. Addict Res Theory. 2020;28:526–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2020.1714037.

Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG. Recovery benefits of the “therapeutic alliance” among 12-step mutual-help organization attendees and their sponsors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.028.

Gorowska M, Tokarska K, Zhou X, Gola MK, Li Y. Novel approaches for treating Internet gaming disorder: a review of technology-based interventions. Compr Psychiatry. 2022;115:152312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152312.

Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:7–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.66.1.7.

Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: peer groups and problem behavior. Am Psychol. 1999;54:755–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.54.9.755.

Macgowan MJ, Wagner EF. Iatrogenic effects of group treatment on adolescents with conduct and substance use problems: a review of the literature and a presentation of a model. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2005;2:79–90. https://doi.org/10.1300/j394v02n01_05.

Liddle HA. Family-based therapies for adolescent alcohol and drug use: research contributions and future research needs. Addiction. 2004;99:76–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00856.x.

Mander J, Schlarb A, Teufel M, Keller F, Hautzinger M, Zipfel S, et al. The individual therapy process questionnaire: development and validation of a revised measure to evaluate general change mechanisms in psychotherapy. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2015;22:328–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1892.

Arias-Pujol E, Anguera MT. Observation of interactions in adolescent group therapy: a mixed methods study. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1188. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01188.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Lausanne.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.B. conceptualized the study, under the supervision of J.B. and W.V. H.B. and D.L.S. were involved in the literature review, study selection, data extraction, and writing of the manuscript. W.V. contributed to the study selection when a third expert was needed. J.B., W.V., and M.F. provided feedback on the review methodology and revised the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The Section Editors for the topical collection Internet Use Disorders are Hans-Jürgen Rumpf and Joël Billieux. Please note that Section Editor Joël Billieux was not involved in the editorial process of this article as he is a co-author.

Competing interests

The last author of this article, Prof. Joël Billieux, serves as an editorial board member and a topical editor for Current Addiction Reports. However, he was not involved at any stage of the review process. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Conflict of Interest

The last author of this article, Prof. Joël Billieux, serves as an editorial board member and a topical editor for Current Addiction Reports. However, he was not involved at any stage of the review process. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boonen, H., Vanderplasschen, W., Sinclair, D.L. et al. Group-Based Interventions for Adolescents with Gaming Disorder or Problematic Gaming Behavior: A Systematic Review. Curr Addict Rep 11, 551–564 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-024-00570-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-024-00570-2