Abstract

Purpose of Review

Alcohol use and associated consequences are among the top preventable causes of death in the USA. Research links high impulsivity and adverse and traumatic experiences (ATEs) to increased alcohol use/misuse, as all three similarly affect brain functioning and development. Yet, studies measuring different specific domains yield differing results. This scoping review examined research articles (N = 35) that examine relations among domains of impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol use.

Recent Findings

Overall, findings indicate that both childhood and lifetime ATEs and all three domains of impulsivity (generalized, choice, and action) are significantly associated with various alcohol and other concurrent substance use measures across age groups. However, variations in results indicate that factors such as timing of assessment, methods, and heterogeneity of construct domains are critical components of these relationships.

Summary

Several research gaps remain. Future research should incorporate multiple domains of the three constructs, and additional longitudinal studies are needed to determine the true nature of the relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For decades, researchers and practitioners have investigated the etiology of alcohol use and associated consequences to inform effective interventions and risk-reduction strategies to improve health outcomes. From a public health perspective, alcohol use and related consequences are among the top preventable causes of death in the USA, responsible for almost 100,000 deaths per year and 2.8 million years of potential life lost [1, 2]. Research also supports relationships between the earlier onset of alcohol use and the development of alcohol misuse, including alcohol use disorder (AUD; [3]. Health practitioners rely on high-quality research to identify profiles of those at risk of alcohol misuse and the reasons for the misuse. Understanding environmental and genetic factors are critical components that influence one’s risk for addiction.

Adverse and traumatic events (ATEs) are environmental experiences that can impact psychological development, health behaviors, and outcomes and may lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or symptoms (PTSS), increased risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and substance use disorders [4, 5]. Experiencing ATEs impacts brain development and function, primarily in the prefrontal cortex (responsible for planning complex behaviors and personality expressions) and how it communicates with the limbic system [6, 7]. These neurological effects also impact decision-making processes and how a person receives and responds to reward stimuli [8]. Similar neurological effects have been observed in people with prolonged substance use [9, 10]. Consequently, many people with a history of ATEs or substance use disorders (SUDs) demonstrate a propensity for impulsiveness.

Impulsivity is defined by Moeller et al. as “a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli without regard to the negative consequences of these reactions to the impulsive individual or to others” (11, p. 1784). Impulsivity is a multidimensional construct measured via self-reports capturing behaviors and characteristics as well as behavioral tasks [12, 13•]. MacKillop and colleagues [12] examined the multidimensionality of impulsivity and further classified it into three categories: impulsive personality, denoting self-reported attributions of one’s ability to self-govern behaviors; impulsive action, denoting the ability to inhibit predominant motor responses; and impulsive choice, denoting discounting of delayed rewards. Impulsive action is typically measured using computer-based reaction time tasks such as stop-signal and go/no-go tasks. Tasks described as capturing difficulties with response inhibition and inhibitory control are under the umbrella of “impulsive action” tasks. Impulsive choice is typically measured using paper-and-pencil or computer-based tasks in which participants indicate preferences between smaller, immediately available and larger, distal rewards (see Fig. 1). These domains of impulsivity may be an essential link in the relationship between ATEs and alcohol and other substance use.

Taxonomy of construct domains, Note: C-DIS-IV = Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version IV; UPPS = The Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, Sensation Seeking, Positive Urgency Impulsive Behavior Scale; SES = Socialization of Emotion Scale; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BIS-11 = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; LEC = Life Events checklist; PCL = Post-traumatic Stress checklist (civilian and service member versions); TLFB = Timeline Follow Back; CAPS = Clinician administered Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Scale; MINI = the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; CSAP = Center for Substance Abuse Prevention Survey; CCPT-II = Connor’s Continuous Performance Test; K-SADS-PL = the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version; FHAM = Family History Assessment Module; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; MBS = Maladaptive Behaviors Scale; ACES = Adverse Childhood Experiences (regular and short form); YAACQ = Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (brief and regular); DRRI-CES = Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory– Combat Experience Scale; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5; EIQ = the Eysenck Impulsivity Questionnaire; ETI = Early Trauma Inventory; BAES = The Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale; SADQ = Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire; TLEQ = Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire; DMQ = Drinking Motives Questionnaire; RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index; LEC = Life Events Checklist; THQ = Trauma History Questionnaire; DDQ = Daily Drinking Questionnaire; LSC = Life Stressor Checklist; SIPAD = Short Inventory of Problems-Alcohol and Drugs; ASSIST = Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test; MAST/AD = Michigan Assessment Screening Test/Alcohol-Drug (short and regular); EATQ = Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire; CWS = Child Welfare Services; CMS = Childhood Maltreatment Scale; mPCCTS = E-modified Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale; mCTS = E-modified Conflict Tactics Scale; OCDS = Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale; ADS = Alcohol Dependence Scale; CHAOS = Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale; YRBS = Youth Risk Behavior Survey; AMIS = The Adaptive and Maladaptive Impulsivity Scale; SLE = Stressful Life Events; TFRS = Tartu Family Relationships Scale; MCQ = Monetary Choice Questionnaire; Ed50 = Effective Delay—50 tasks; CUDIT = Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test; CQ-SF-R = Cravings Questionnaire Short Form Revised; QFI = Quantity/Frequency Index; STRAIN = Stress and Adversity Inventory for Adults; SSAGA = Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism; AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder; BTQ = Brief Trauma Questionnaire; ETISR = Early Trauma Inventory Self-Report; SES = Sexual Experiences Survey; CBQ = Childhood Behavior Questionnaire; TMCQ = Temperament in Middle Childhood Questionnaire; SRD = Self-Report of Deviance; RACS = Relationship Affect Coding System; AOAC = Age of Onset of Alcohol Consumption

The maladaptive influence of impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol use tend to have similar effects on brain functioning and development [8, 9, 14]. Researchers posit that these constructs have reciprocal relationships, consequently triggering the reoccurrence of each other through their impacts on decision-making and inclination to seek rewards without optimal consideration of consequences [15, 16]. Given the reciprocal, biopsychosocial impact of impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol use, a review of recent findings summarizing and charting how all three relate to each other could inform future mental/physical health and research initiatives.

There are several challenges with summarizing and synthesizing findings regarding these constructs. In addition to the methodological complexity of impulsivity, variations in the delineation and measurement of impulsivity have led to a lack of clarity in findings. Research has shown that measures of different impulsivity domains are often not strongly related [12, 13•, 17]. Additionally, impulsivity measures are frequently combined with similar yet distinct constructs (e.g., sensation seeking, emotion regulation) that do not align with all aspects of Moeller and colleagues’ definition of impulsivity. Therefore, this scoping review focused on measures of impulsivity that as follows: (1) align with all aspects of Moeller and colleagues’ [11] seminal definition of the impulsivity construct, (2) could be classified according to the generalized/action/choice taxonomy of impulsivity [12], and (3) were examined independently of other separate but related constructs.

ATEs are also intricate in that what constitutes an ATE varies by person, developmental timing (i.e., when it occurred in the lifespan), and the event itself. While related, adverse experiences and trauma are distinct constructs. Adverse experiences are potentially traumatic events that pose a severe threat to a person’s physical or psychological well-being, whereas trauma is a possible outcome of exposure to an event when it is both perceived as traumatic and induces a prolonged and severe stress response [18, 19]. Common examples of these types of events include abuse and neglect, severe accidents and injuries, bullying and discrimination, and domestic and community violence [18, 19]. How a person perceives the severity of an ATE can vary depending on multiple factors, including genetics, visual and physical proximity to the event, the time elapsed since the event, the nature of the event (e.g., physical, emotional, natural disaster), and the people involved (e.g., self, caregivers, neighbors; 18, 20,21,22). Therefore, two people could experience the same adverse event yet perceive its impact differently, resulting in the experience being traumatic for one but not the other. Additionally, ATEs have been found to have a cumulative effect on health outcomes [19, 23, 24]. Event classification and perception, paired with the developmental timing of ATEs, should be considered when examining ATE influences on health behaviors, such as substance use.

Latent profile analyses consistently find that people who have experienced more ATEs and are more impulsive have a higher risk of developing AUD, making these critical risk factors for addiction screening and intervention [25•, 26•, 27]. However, identifying those at greatest risk is only part of reducing alcohol misuse. Understanding why an individual may be at a greater risk for SUDs, including AUD, is critical to combat this public health crisis. Additionally, research on these constructs can be assessed for (i.e., time of event) and at (i.e., time of assessment) varying points and neurological development in a person’s lifespan, potentially leading to variations in their relationships with AUD. To better inform future interventions and health practices, it was pertinent to focus on the most recent findings that clarify and identify relationships among specific components of the impulsivity, ATE, and alcohol use/misuse constructs across different age groups.

Several recent empirical reviews have only partially addressed relations among impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol use [28••, 29•, 30, 31••, 32]. For instance, reviews have addressed only two of the three constructs [32, 33] or have not directly addressed the multidimensional qualities of these constructs, which could influence results (e.g., only examine childhood adversity; [29•, 31••, 34, 35]. Due to their multidimensional nature, it is imperative to precisely identify individual domains under each broader construct (i.e., impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol use/misuse) and chart relationships among those specific domains, with careful attention to sample population, measurement, and study design. While there are a few theory-based approaches to this research topic, such as the self-medication theory [36], results have been equivocal. Therefore, we opted for an explicit and comprehensive approach for this review. Accordingly, scoping reviews are uniquely suited for synthesizing and identifying trends and gaps across complex constructs in related yet separate research areas [37]. This review uses a scoping approach to synthesize relevant findings from recent literature categorized by domain measures, characterize trends among constructs, and identify future research needs.

The Current Review

This scoping review compiles and synthesizes recent research contributions examining relationships among impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol and other substance use domains. To our knowledge, this topic has not been sufficiently scoped to date; therefore, we aim the following: (1) identify and categorize specific domains of impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol use and corresponding results; (2) determine if different domains of impulsivity and ATEs, measured at and related to different points in the lifespan, yield different results as they relate to substance use/misuse; and (3) identify measurement gaps in the literature from the last 5 years to inform current practice and future research. This scoping review follows Arksey and O’Malley’s [38] methodological approach. This framework includes five stages:

-

Stage 1: Identifying the research question,

-

Stage 2: Identifying the relevant studies,

-

Stage 3: Study selection,

-

Stage 4: Charting the data, and

-

Stage 5: Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results [38].

Method

Stage 1: Research Question

The research question guiding this scoping review was: What is the recent empirical research on associations among impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol and other concurrent substance use? Accordingly, to be included in the review, studies were required to measure impulsivity in a manner that conformed to Moeller and colleagues’ [11] definition of the construct and needed to fit into the three-domain taxonomy of impulsive choice, impulsive action, and impulsive personality, which, for this review, will be referred to as generalized self-reported impulsivity [12]. ATEs included childhood and lifetime/adult ATEs, or a combination of both, PTSD diagnoses, or varying severity of PTSS. Alcohol use and related behaviors could be measured in various ways (e.g., frequency, quantity, peak consumption within a given period) on its own or in conjunction with other substance use.

Stage 2: Identifying the Relevant Studies

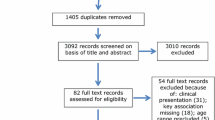

Comprehensive searches of empirical literature were conducted electronically between September 19, 2022, and January 24, 2023, using the search strings: (alcohol* OR “substance use” OR “substance abuse”) AND (impuls* OR urgency OR disinhibit* OR self-control OR “inhibitory control” OR “interference control” OR “cognitive control” OR “executive function” OR “state trait” OR discounting) AND (advers* OR “adverse childhood experiences” OR ACEs OR “child* abuse” OR “child* neglect” OR child* trauma* OR maltreatment OR “sex* abuse” OR “sex* molest*” OR “physical abuse” OR “emotional abuse” OR “lifetime trauma*” OR “stress disorder*” OR “stress symptom*” OR PTSD OR PTSS OR “adult trauma*” OR “neighbor* violence” OR “traumatic experience*” OR “lifetime stress” OR “chronic stress” OR “toxic stress” OR “domestic violence” OR “domestic abuse” OR “interpersonal abuse” OR “interpersonal violence” OR “minority stress”). The search was conducted across all EBSCOhost, PubMed, and ProQuest databases. Results were limited to publications that were (a) peer-reviewed; (b) in English; and (c) published between 2018 and 2023. An “AB” filter was applied, limiting results to those where the search terms are found in the abstract, and duplicates were removed. A hand-search of reference lists of relevant literature reviews and specialized journals did not yield additional results (see Fig. 2 for details).

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [90]

Stage 3: Study Selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied by hand screening the 1,510 remaining articles [38]. Articles were included if: (a) results from at least one statistical model capturing relationships among the three primary constructs (i.e., impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol/substance use) were reported; (b) quantitative results were reported; (c) human subjects were enrolled; (d) researchers measured and examined impulsivity as previously defined, independently of other, separate but related constructs; and (e) researchers who grouped participants by their patterns of substance use (e.g., heavy alcohol use) also included a comparison group (e.g., abstinence, moderate alcohol use), or reported variations within the grouping variable that could be related to the other constructs (see Fig. 2). A total of 35 articles were included in Stage 4.

Stage 4: Charting the Data

The 35 studies included in the review were read and reviewed for key methods and findings to collate, summarize, and report in Stage 5. Most studies considered how impulsivity mediated or moderated relationships between ATEs/symptom severity and concurrent alcohol/substance use.

Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

The selected quantitative articles were synthesized and collated to depict best and compare the results [38]. The data were divided into subgroups based on domain measures, sample age, and findings around the primary constructs (see Fig. 2 for domain taxonomies of constructs). Results are reported based on themes identified through a synthesis of the literature.

Results

A total of 35 articles were included, reporting results concerning childhood ATEs (n = 19), lifetime ATEs (n = 13), and a combination of both (n = 3). All 13 lifetime ATE studies reported a PTSD variable, whereas only one combination ATE study and two childhood ATE studies did. Most studies exclusively examined generalized, self-reported impulsivity. Four studies focused solely on impulsive action, three on impulsive choice, and seven examined a combination of generalized and behavioral impulsivity. Most had cross-sectional designs (n = 26). Of the nine longitudinal studies, only two considered lifetime ATEs. See Table 1 for study details. Accordingly, results are reported based on these distinguishing variables.

Childhood Adversity

Generalized, Self-Reported Impulsivity

Adult Samples

Support for generalized impulsivity as a mediator between childhood ATEs and AUD varied across adult studies. One study of males with AUD separated components of generalized impulsivity scales, the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11; 39) and the Impulsive Behavior Scale and subscales (UPPS; 40), into two factors, “reflection” and “response” impulsivity. They found that childhood ATEs related significantly to AUD severity and age of drinking onset. While both impulsivity domains were significant mediators of the association between childhood ATEs and AUD severity, only reflection impulsivity mediated the association between childhood ATEs and age of drinking onset [41]. Another study found that impulsivity and childhood ATE prevalence were significantly higher in adults with AUD than in healthy controls [42], and while impulsivity was significantly, positively correlated with both severity of addiction and experiencing emotional abuse, only emotional abuse, not impulsivity, was a significant risk factor for AUD [42]. In a study of women with bulimic-spectrum disorders, impulsivity did not mediate the association between childhood ATEs and substance use, but emotion dysregulation did [43]. The final study examined if negative urgency (a tendency to commit rash or regrettable actions as a result of an intense negative mood; 43) [44] mediates the relation between emotion-based ATEs (i.e., childhood emotional abuse and neglect) and alcohol use [45]. These researchers found that emotion-based ATEs predicted higher negative urgency, significantly mediating the association between emotion-based ATEs and problematic drinking scores. Collectively, emotion-related childhood ATEs seem to be associated with alcohol use, and there was mixed evidence showing that the relationship is mediated by generalized impulsivity in adults.

College-Aged Samples

Two cross-sectional studies examined impulsivity as a mediator between childhood ATEs and alcohol use and related consequences in college student samples [46, 47]. Espeleta and colleagues [47] used cumulative ATE scores, UPPS scores for negative and positive urgency, and an emotion dysregulation measure with an impulse subscale. Neither type of urgency was a significant predictor of alcohol consequences, nor did they significantly mediate relations between ATEs and alcohol consequences when entered in parallel, while emotion dysregulation did. However, when entered serially, there was a statistically significant indirect effect between childhood ATEs and alcohol-related consequences mediated by emotion dysregulation to positive urgency. Brown and colleagues [46] took a different approach, using the BIS-11 to measure impulsivity, parsed out subcategories of childhood ATEs, and examined them with alcohol use frequency. Only emotional abuse was associated with impulsivity, with impulsivity mediating associations between emotional abuse and past-month alcohol use frequency. These studies used different measures, had different findings regarding impulsivity as a cross-sectional mediator in the relation between childhood ATEs and alcohol outcomes, and included samples with low occurrences of ATEs. Yet, both studies found that emotion-related constructs were significantly associated with alcohol-related outcomes.

Adolescent Samples

In a longitudinal study, Otten and colleagues [48•] observed children aged 2 to 14 from high-risk communities. They examined effects of cumulative consequences over time across developmental ages, ecological levels, and systems [49]. Results showed that negative parent interactions and childhood ATEs assessed between ages 2 and 5 were significantly inversely related to inhibitory control (i.e., lower impulsivity) assessed at ages 7 and 8. Lower inhibitory control was significantly associated with problematic externalizing behaviors at ages 9 and 10, and these behaviors, along with parental drug use, were associated with substance use by age 14. This study suggests that negative parent interactions and childhood ATEs may influence externalizing behaviors related to impulsivity, increasing substance use at a younger age [48•].

Impulsive Action

College-Aged Samples

Two cross-sectional studies examined whether impulsive action mediated the relation between cumulative childhood ATEs and drinking consequences among college student samples [50, 51]. Neither study indicated that impulsive action was significantly associated with childhood ATEs, and total childhood ATE scores were not significantly associated with drinking outcomes.

Adolescent Samples

A cross-sectional study assessing impulsive action, childhood ATEs, and AUD found that adolescents with AUD and ATEs demonstrated less inhibitory control (i.e., were more impulsive) during tasks than the AUD group without ATEs and healthy control group [52•]. Additionally, adolescents with AUD and ATEs had significantly larger left pars triangularis, part of the prefrontal cortex associated with cognitive memory, speech, and language, and less corpus callosum volume, which facilitates hemisphere communication and has been linked to inhibitory control functioning [52•, 53]. ATEs may lie at the core of these associations between impulsive action and AUD, given that the AUD and ATE groups consistently demonstrated less inhibitory control. Yet, results are limited and inconsistent across age groups.

Impulsive Choice

Adult Samples

Two studies explored associations among impulsive choice as measured via delay discounting tasks (i.e., an individual’s preference for a small, immediate reward over a larger, delayed reward; 53, 54), childhood ATEs, and alcohol use in adult populations. A cross-sectional study revealed participants with SUDs and a family history of SUD had significantly higher impulsive choice, even when accounting for childhood ATEs. Childhood ATEs were also significantly and positively associated with impulsive choice, regardless of SUD status or family history [55]. The second was a longitudinal study that found that in participants with poor stress regulation, higher impulsive choice significantly mediated the relationship between childhood ATEs and alcohol use outcomes [56].

Adolescent Samples

One longitudinal study examined impulsive choice and adolescents with childhood ATE exposure and future substance use. Results indicated that having more childhood ATEs increased amygdala activity in response to higher-risk options in the impulsive choice task and that increased amygdala activity during the task mediated the association between childhood ATE scores at baseline and substance use at year three (after controlling for baseline substance use) [57]. All three behavioral studies on impulsive choice found significant relations among variables, indicating a possible trajectory wherein childhood ATEs influence the development of impulsive choice, which may influence alcohol use.

Generalized, Self-Reported, and Action Impulsivity

College-Aged Samples

Two longitudinal studies conducted with college-aged young adults examined task-related neural activity and familial trends in people with a history of varying childhood ATEs. Both studies found that people with a history of both childhood ATEs and a family history of AUDs had significantly more AUD symptoms than those without [58••, 59••] Additionally, both studies examined prefrontal neural activation during impulsive action tasks and found that those with childhood ATEs (sexual abuse, [59••] and maltreatment, [58••]) had significantly weaker task-related prefrontal neural network activity. Participants with childhood ATEs showed less prefrontal brain activation, of which participant AUD risk factors were a significant predictor [59••]. Meyers and colleagues found that sexual ATEs significantly predicted less prefrontal brain activation during the impulsive action task after accounting for other non-assaultive traumas, participant alcohol use, and family history of AUD, but not when generalized impulsivity scores were included, indicating generalized impulsivity may play a significant role in this association. Elton and colleagues found that male college students with childhood ATEs and less family history of AUD had higher generalized impulsive traits than females and poorer response inhibition [58••]. In contrast, males with more childhood ATEs and a family history of AUD had stronger response inhibition task performance and accompanying task-related prefrontal brain activation during tasks, possibly indicating increased resilience in this subsample. Overall, participants demonstrating greater task-related neural network activity also reported less generalized impulsivity and reduced alcohol misuse, despite some being in a higher risk category for AUD, suggesting that resilience is possible despite a challenging environment and family history.

Adolescent Samples

Two studies evaluated potential mechanisms underlying relationships between generalized and action impulsivity and early-onset alcohol misuse among adolescents with histories of ATEs. A 2-year study of adolescents involved in the child welfare system found significant associations between ATEs and decreased generalized and action scores and between decreased generalized and action scores and subsequent alcohol use at follow-up. Additionally, decreased generalized and action impulse scores significantly mediated the association between childhood ATEs and adolescent alcohol use [60••]. Another study found that children living in stressful (compared to supportive) family environments demonstrated greater generalized and action impulsivity and alcohol use by age 15, with a higher prevalence of lifetime AUD in adulthood [61••]. These findings suggest that stressful and less supportive environments for youth and adolescents may lead to increased generalized impulsivity and substance use outcomes.

Generalized, Self-Reported, Action, and Choice Impulsivity

Adult Samples

Only two studies examined associations among all three impulsivity domains, childhood ATEs, and substance use in adult samples. The first was cross-sectional and examined whether different impulsivity domains mediated the relation between childhood ATEs and substance use in two adult samples [62•]. Generalized, negative urgency and impulsive choice were significant mediators between childhood ATEs and substance use, but impulsive action and positive urgency were not [62•]. The second was a non-randomized experimental study examining the effects of alcohol administration in the laboratory across domains of impulsivity among women with and without a history of childhood sexual abuse and other ATEs [63•]. At baseline and throughout the alcohol administration session, women with a history of childhood ATEs had significantly poorer performance on impulsive action tasks than those without childhood ATEs but only marginally greater generalized impulsivity and delayed discounting. Impulsive responding on behavioral tasks increased with each lab-administered alcohol dose in both groups; however, only women with a history of childhood ATEs demonstrated alcohol-induced increases in response inhibition. While both studies found people with childhood ATEs to be more impulsive, Evans and Reed [63•] found that alcohol use significantly decreased inhibitory control for those with a history of childhood ATEs.

Childhood and Lifetime Adversity

Generalized, Self-Reported Impulsivity

Adult Samples

One cross-sectional study of adults examined generalized impulsivity as a pathway between ATEs and alcohol use outcomes, measuring childhood ATEs in one sample and lifetime ATEs in a second sample [64•]. Junglen and colleagues [64•] found that negative urgency and PTSS severity independently and jointly mediated the relation between emotional abuse and neglect with substance use among both samples. Among adult samples, both childhood and lifetime events played significant roles in alcohol use outcomes, with generalized impulsivity mediating those relationships.

College-Aged Samples

One cross-sectional study of college students considered childhood ATEs, impulsivity, alcohol use severity, and lifetime sexual ATEs among females [65]. Results indicated that childhood ATEs were significantly associated with lifetime sexual ATEs through higher generalized impulsivity and alcohol use severity scores, suggesting that impulsivity and alcohol use have key roles in the risk of additional lifetime ATEs [65]. For students with a history of childhood ATEs, higher generalized impulsivity coupled with alcohol use problems may leave one more susceptible to additional lifetime ATEs, potentially contributing to cyclical relationships among constructs. McMullin et al. [66] compared early childhood ATEs (before age 12) and lifetime ATEs (after age 18) in college students. They found that greater overall ATEs were significantly related to more negative urgency, and all subscales of generalized impulsivity were significantly related to alcohol consequences; however, generalized impulsivity did not mediate the relation between ATEs and alcohol consequences. Additionally, they found that only adult ATEs predicted alcohol consequences, yet the sample examined was between 18 and 25, possibly influencing results due to event proximity. All three combination ATE studies reported that generalized impulsivity, particularly negative urgency, mediates the association between childhood and lifetime ATEs and general alcohol use but not alcohol-related consequences.

Lifetime Adversity

Generalized, Self-Reported Impulsivity

Adult Samples

Most lifetime ATE studies that measured generalized impulsivity examined participants at high risk of exposure to adult ATEs, such as people in the military or civil service. Among cross-sectional studies enrolling veterans, researchers have found positive correlations between generalized impulsivity and PTSS severity and drinking behaviors; that lifetime ATEs were a significant predictor of impulsivity, but drinking behavior was not [67]; that PTSS (i.e., reexperiencing events and avoidance/numbing) was significantly associated with several drinking measures (e.g., being at high risk of AUD, peak number of drinks in a day, number of heavy drinking days, and weekly average drinks; [67, 68]); and that PTSD and alcohol use outcomes were significantly correlated with negative urgency [68, 69], and that relationships between PTSD and alcohol outcomes were moderated by negative urgency [69, 70]. This relationship indicates that veterans with high levels of PTSD and generalized impulsivity were more likely to report greater alcohol use than veterans with lower levels of impulsivity. Similar findings were found in a cross-sectional study of firefighters. Specifically, PTSS severity and impulsivity were significantly associated with alcohol use severity, wherein heightened PTSS severity and impulsivity had the highest alcohol use severity [71]. Research involving military and firefighters suggests that severe lifetime ATEs and PTSD symptom severity relate to alcohol use and that heightened generalized impulsivity, particularly negative urgency, strengthens the association.

Two studies longitudinally examined lifetime ATEs and their relationship to generalized impulsivity and alcohol use among military veteran samples. The first used momentary daily assessments where participants reported real-time acute PTSS and tested if these symptoms were related to alcohol use via generalized impulsivity [72]. Researchers found that increased PTSS severity from the participant’s last momentary assessment was positively associated with the number of drinks in the subsequent assessment, and this relationship was significantly moderated by higher generalized impulsivity [72]. The other study examined if participants’ generalized impulsiveness impacted treatment outcomes for PTSD and SUDs [73]. Findings showed that pretreatment impulsivity did not significantly predict posttreatment PTSD severity or posttreatment alcohol craving severity [73]. In summary, these longitudinal studies indicate that increased momentary PTSS severity among veteran populations is related to increased alcohol use, especially among people with higher levels of generalized impulsivity. However, impulsivity itself may not be an essential predictor of PTSD-SUD treatment outcomes in this population.

College-Aged Samples

The remaining four studies focused on lifetime ATEs in college-aged young adults and examined relations among ATEs, PTSS, generalized impulsivity, and alcohol use. Two studies found that lifetime ATEs were significantly related to alcohol use and consequences, but negative urgency did not moderate the relationship between lifetime ATEs and alcohol outcomes [74, 75]. The final two studies found that alcohol consumption, PTSD, and lifetime ATEs were significantly related and that these constructs were significantly associated with increased generalized impulsivity [76, 77]. Results from these college-aged population studies indicate significant relationships between lifetime ATEs and alcohol use; however, the association of these constructs with generalized impulsivity is inconclusive.

Impulsive Action

Adult Samples

Only one study for lifetime ATEs measured impulsive action, and no studies examined impulsive choice independent of other impulse domains. Esterman and colleagues examined relations among lifetime ATEs, PTSS, SUDs, and impulsive action in a veteran sample with and without traumatic brain injuries [78]. They found that both PTSD and SUDs were significantly associated with reduced inhibitory control and that having comorbid PTSD with active PTSS and SUDs was associated with higher rates of inhibitory control failures during a response inhibition task [78]. While this study indicated an association among impulsive action, lifetime ATEs, and alcohol use, additional research is needed for behavioral impulsivity measures.

Generalized, Self-Reported and Choice Impulsivity

Adult Samples

Only one lifetime ATE study examined generalized and behavioral impulsivity, specifically impulsive choice, in a cross-sectional study of adults with at least one lifetime ATE [79•]. Researchers investigated associations among PTSS, alcohol use, and impulsivity. They found that people who reported PTSS endorsed more generalized impulsivity and evinced greater delay discounting than participants without PTSS. Moreover, people with PTSS reported significantly higher SUD scores, including AUD, and the relation between PTSS and substance use was significantly mediated by generalized impulsivity scores, primarily positive urgency. While this study indicated significant associations among impulsivity, lifetime ATEs, and alcohol use, additional research is needed.

Discussion

Alcohol misuse poses a significant yet preventable public health crisis from adolescence through adulthood, with research linking impulsivity and ATEs to increased alcohol and other substance use. This scoping review aimed to compile and synthesize emerging empirical research that examines relations among impulsivity domains, ATEs, and alcohol/substance-related outcomes. Specifically, we aimed to (1) identify and categorize specific domains of impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol use and corresponding results; (2) determine if different domains of impulsivity and ATEs, measured at and related to different points in the lifespan, yielded different results as they related to substance use/misuse; and (3) identify measurement gaps in the literature from the last 5 years to inform future research and practice. Overall, findings indicate that both childhood and lifetime ATEs and the three domains of impulsivity we examined (generalized, choice, and action) are significantly associated with various alcohol and other concurrent substance use measures across age groups. However, some domains yielded inconsistent results (Table 2). Accordingly, several research gaps remain to determine the precise nature of relationships among impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol-related outcomes.

Most studies examining adolescent and adult populations indicated significant relationships between ATEs and alcohol and other substance use measures. These relationships were often found to be significantly mediated by generalized, self-reported impulsivity and impulsive choice. This pattern of findings applied to both childhood and lifetime ATEs and various alcohol use outcomes in longitudinal, cross-sectional, and experimental studies. Alcohol use quantity and frequency measures showed positive relations with cumulative ATEs and ATE severity, or PTSS, in most studies. These trends across both childhood and lifetime ATEs support prior research on the cyclical nature of these events, namely that exposure to childhood ATEs is linked to greater impulsivity, which is linked to greater substance use, leading to further lifetime ATE exposure [15, 16, 65].

In aim two, we examined if different domains yielded different results when measured at and related to different points in the lifespan. Most result discrepancies came from studies examining college-aged people, impulsive action, and negative alcohol-related consequences. These inconsistencies may be due to multiple factors, including timing of assessment, methods, and heterogeneity specific to these construct domains.

Timing of assessment poses a challenge in college-aged samples for several reasons. The first is due to the lifespan proximity between adult and lifetime ATEs and childhood ATEs. College-aged young adults are closer in time to childhood ATEs than general adult populations, and some are still considered in the range of childhood ATEs, as assessment is through age 18. However, studies that assess adult and lifetime ATEs may not distinguish the timeline of events, and studies that evaluate both lifetime and childhood may cross multiple lifespan periods or not measure different lifespan periods as intended. Secondly, research shows that college students report higher than average ATE prevalence than the general population [80]. While occurrences of ATEs are cyclical, these events may have current psychological effects that distort recall and significance of childhood ATEs that occurred many years prior [81], which may lead to nonsignificant findings when assessing the self-reported impact of these events on current behaviors.

Another timing assessment issue with college-aged samples is differences in development. College-aged samples are still relatively early in the lifespan and still amid neurological development of brain regions associated with impulsivity, and may be fine-tuning coping mechanisms for ATEs [82, 83]. Individuals in this age range may be at different stages of development, leading to larger variances across outcomes in impulsivity, alcohol, and other substance-related measures, as well as demonstrated levels of resiliency. Furthermore, while some PTSD findings are similar between college and the general population [82], college students do not represent a cross-section of young adults with childhood ATEs. Given that admission to and remaining in college requires a degree of achievement and mental and emotional functioning, college students are more likely to be resilient than non-student peers [84], which has been linked with lower PTSS and healthier coping mechanisms [85].

Resiliency levels may influence results for impulsive action tasks and consequence assessments. Results from adult and college-aged samples that examined inhibitory control and risk-taking indicated that many individuals with high childhood ATE scores generally exhibited more caution, performed better on inhibitory control tasks, and took fewer risks than individuals with lower childhood ATE scores [58••, 63•]. The authors attributed these findings to high levels of resilience, which may help to explain differences between these outcomes and the three adolescent studies where high ATEs were significantly related to higher impulsive action [52•, 60••, 61••], as resiliency may not have fully developed yet in this age group. Alternatively, null and inconsistent results across impulsive action assessments could also result from heterogeneity across impulsivity domains. Impulsive action tasks may capture momentary effects to a greater extent than enduring individual differences in contrast to generalized and choice impulsivity measures [86, 87]. Deciding among these explanations would require longitudinal research, which is currently minimal [15].

Additionally, individual differences other than the magnitude of alcohol consumption influence experiences of negative consequences. These may include an individual’s degree of impulsivity/inhibitory control, the physical and social contexts in which one typically drinks, risk-taking, and sensation-seeking tendencies [88]. Based on these factors, an individual could consume high volumes of alcohol regularly without endorsing many severe consequences (e.g., driving while intoxicated). Researchers should consider these factors when selecting ATE, impulsivity, and alcohol use measures, especially when sampling from college-aged populations.

Additional research is needed, including longitudinal methodology and assessment of specific ATE, impulsivity, and substance use/misuse domains. For methodology, most studies in this review were cross-sectional. While results predominantly supported impulsivity as a mediating pathway between ATEs and alcohol use behaviors, cross-sectional mediation is not mediation in the truest sense [89]. Prospective and longitudinal designs are urgently needed and may be more suitable due to the observational nature of ATEs and their cumulative impact on development and health factors, which can only be adequately identified in prospective research. Ideally, these studies would take place during adolescence, as that is the peak of an individual’s neurodevelopment, and can capture the effects of childhood ACEs as they transpire. However, research engaging adolescent samples is sparse, with only five out of the 19 childhood ATE studies included in this review examining adolescents.

Longitudinal studies enrolling adolescents could indicate precisely how childhood ATEs impact development, including impulsivity, later-life substance use, and recurring lifetime ATEs. Future research must examine not only the impact an event had on the child, such as screening for PTSD/PTSS but also screening for resilience. While diagnostic interviews may be rare in childhood ATE research, assessing the significance of an event could be a critical component in neurodevelopmental variances and an individual’s impulsivity across samples with childhood ATEs. Only one childhood ATE study reported PTSD/PTSS outcomes, yet several studies demonstrated reduced prefrontal brain activation during impulsive choice and action tasks significantly related to cumulative childhood ATE exposure [52•, 58••, 59••]. It is unknown if differences exist between the impact of cumulative versus highly impactful, singular ATEs on the neurodevelopment of impulsivity and how this may relate to substance use behavior and recurring lifetime ATEs subsequently.

Furthermore, only one lifetime ATE study of adults with PTSD included a delineated screening for childhood ATEs. Without this, lifetime ATE research might obscure the adverse effects of experiencing ATEs during key developmental periods and their relation to adult PTSS severity and impulsivity. Tracking these neurodevelopment changes by impulsivity domain across periods of the lifespan may provide more precise details on the development of impulsivity, the effects of cumulative and severity of ATEs on the brain during the lifespan, and the relationship between these constructs.

Most studies relied heavily on generalized impulsivity measures. Only two studies examined all three domains of impulsivity addressed in this review. Impulsivity is a multidimensional construct [12, 17]. Each domain captures unique aspects of impulsivity. Generalized, self-reported impulsivity captures self-identified traits, action captures how one reacts to and resists compelling stimuli, and choice assesses decision-making about reward evaluations [12]. Due to the heterogeneity of findings across these domains, it is important to acknowledge that they measure unique components that cannot be accounted for entirely by simply using the term “impulsivity.” Additionally, there may be differences in the impact of ATEs on these domains, which may, in turn, have varying impacts on substance use outcomes. To predict outcomes more precisely for substance use interventions, it is vital to understand how ATEs impact each impulsivity domain and how each, in turn, affects substance use outcomes.

Conclusion

This review highlights crucial relationships among domains of impulsivity, ATEs, and alcohol use. Due to the multidimensional nature of the three constructs on brain development, future research should consider prospective and longitudinal designs. Assessing multiple domains under each umbrella construct is essential to understanding associations of these constructs with alcohol and other substance misuse interventions. Acknowledging that the proposed research designs take a considerable amount of time and can only include a limited amount of measures per study, it is essential to include and define multiple domains of these constructs to understand the precise nature of the assessed relationships. Domains of these constructs are often lumped under their generalized umbrella terms, risking oversimplification and even misconstruing relationships. Greater specificity increases the likelihood of results that will inform the development of interventions that are in step with the principles of precision medicine. New, precision interventions would strengthen evidence-based practice, with goals of increasing resilience, mitigating the impact of ATEs, and reducing or preventing alcohol and other substance misuse.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, Echko M, Glenn S, Olsen HE, Mullany E, et al. The state of US health, 1990–2016. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1444.

White AM, Castle IJP, Powell PA, Hingson RW, Koob GF. Alcohol-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2022;327(17):1704.

Grant BF, Stinson FS, Harford TC. Age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: a 12-year follow-up. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(4):493–504.

Dube SR, Fairweather D, Pearson WS, Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Croft JB. Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(2):243–50.

Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(3):174–86.

Armbruster D, Moser DA, Strobel A, Hensch T, Kirschbaum C, Lesch KP, et al. Serotonin transporter gene variation and stressful life events impact processing of fear and anxiety. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(3):393–401.

Hart H, Rubia K. Neuroimaging of child abuse: a critical review. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:52.

Galandra C, Basso G, Cappa S, Canessa N. The alcoholic brain: neural bases of impaired reward-based decision-making in alcohol use disorders. Neurol Sci. 2018;39(3):423–35.

Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):760–73.

Amico E, Dzemidzic M, Oberlin BG, Carron CR, Harezlak J, Goni J, et al. The disengaging brain: dynamic transitions from cognitive engagement and alcoholism risk. Neuroimage. 2020;209:116515.

Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, Schmitz JM, Swann AC. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1783–93.

MacKillop J, Weafer J, Gray JC, Oshri A, Palmer A, de Wit H. The latent structure of impulsivity: impulsive choice, impulsive action, and impulsive personality traits. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(18):3361–70.

• Creswell KG, Wright AGC, Flory JD, Skrzynski CJ, Manuck SB. Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity-related measures in relation to externalizing behaviors. Psychol Med. 2019;49(10):1678–90. Examines the importance of domain distinction within the construct of impulsivity when studying externalized behaviors, such as substance use.

Hart KL, Brown HE, Roffman JL, Perlis RH. Risk tolerance measured by probability discounting among individuals with primary mood and psychotic disorders. Neuropsychology. 2019;33(3):417–24.

Hien DA, Lopez-Castro T, Fitzpatrick S, Ruglass LM, Fertuck EA, Melara R. A unifying translational framework to advance treatment research for comorbid PTSD and substance use disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;127:779–94.

López-Castro T, Hu M-C, Papini S, Ruglass LM, Hien DA. Pathways to change: use trajectories following trauma-informed treatment of women with co-occurring post-traumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2015;34(3):242–51.

Dick DM, Smith G, Olausson P, Mitchell SH, Leeman RF, O’Malley SS, et al. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addict Biol. 2010;15(2):217–26.

Bartlett J, Sacks V. Adverse childhood experiences are different than child trauma, and it’s critical to understand why. Child Trends [online]. 2019. Available from: https://www.childtrends.org/adverse-childhood-experiences-differentthan-child-trauma-critical-to-understand-why. Accessed 21 Feb 2023.

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–58.

Lancaster SL, Melka SE, Rodriguez BF, Bryant AR. PTSD symptom patterns following traumatic and nontraumatic events. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2014;23(4):414–29.

Ortiz R, Gilgoff R, Burke HN. Adverse childhood experiences, toxic stress, and trauma-informed neurology. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(6):539–40.

Shern DL, Blanch AK, Steverman SM. Toxic stress, behavioral health, and the next major era in public health. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86(2):109–23.

Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(8):e356–66.

Kira IA, Fawzi MH, Fawzi MM. The dynamics of cumulative trauma and trauma types in adults patients with psychiatric disorders: two cross-cultural studies. Traumatology. 2013;19(3):179–95.

• DeMartini KS, Gueorguieva R, Pearlson G, Krishnan-Sarin S, Anticevic A, Ji LJ, et al. Mapping data-driven individualized neurobehavioral phenotypes in heavy alcohol drinkers. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2021;45(4):841–53. Examines latent profiles of individuals with alcohol misuse, including a proclivity for impulsivity and a history of ATEs.

• Kwako LE, Schwandt ML, Ramchandani VA, Diazgranados N, Koob GF, Volkow ND, et al. Neurofunctional domains derived from deep behavioral phenotyping in alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(9):744–53. Examines latent profiles of individuals with alcohol misuse, including a proclivity for impulsivity and a history of ATEs.

Shin SH, McDonald SE, Conley D. Profiles of adverse childhood experiences and impulsivity. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;85:118–26.

•• al’Absi M, Ginty AT, Lovallo WR. Neurobiological mechanisms of early life adversity, blunted stress reactivity and risk for addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2021;188:108519. A review and proposed model of how childhood ATEs lead to risk for substance use addiction through an altered motivational and behavioral reactivity to stress that contributes to disinhibited behavioral reactivity and impulsivity.

• Hoffmann JP, Jones MS. Cumulative stressors and adolescent substance use: a review of 21st-century literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2022;23(3):891–905. A review of empirical studies from the last two decades that have examined the association between cumulative stressors and adolescent substance use.

Lane AR, Waters AJ, Black AC. Ecological momentary assessment studies of comorbid PTSD and alcohol use: a narrative review. Addict Behav Rep. 2019;10:100205 A review of research on ecological momentary assessment (EMA) examining the associations between PTSD symptoms and alcohol-related variables.

•• Liu RT. Childhood maltreatment and impulsivity: a meta-analysis and recommendations for future study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47(2):221–43 A systematic meta-analysis of the empirical literature on childhood maltreatment and impulsivity.

Perez-Balaguer A, Penuelas-Calvo I, Alacreu-Crespo A, Baca-Garcia E, Porras-Segovia A. Impulsivity as a mediator between childhood maltreatment and suicidal behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;151:95–107.

Sliedrecht W, Roozen HG, Witkiewitz K, de Waart R, Dom G. The association between impulsivity and relapse in patients with alcohol use disorder: a literature review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2021;56(6):637–50.

Duffy KA, McLaughlin KA, Green PA. Early life adversity and health-risk behaviors: proposed psychological and neural mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1428(1):151–69.

Kosecka K, Stelmach E. Childhood trauma and the prevalence of alcohol dependence in adulthood. Curr Probl Psychiatry. 2020;21(4):288–93.

Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–44.

Rumrill PD, Fitzgerald SM, Merchant WR. Using scoping literature reviews as a means of understanding and interpreting existing literature. Work. 2010;35(3):399–404.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–74.

Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality Individ Differ. 2001;30(4):669–89.

Kim ST, Hwang SS, Kim HW, Hwang EH, Cho J, Kang JI, et al. Multidimensional impulsivity as a mediator of early life stress and alcohol dependence. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):4104.

Guürgen A, Oyekçin DG, Deniz-Özturan D. Emotion regulation difficulties and childhood trauma are associated with alcohol use severity: a comparison with healthy volunteers. Middle Black Sea J Health Sci. 2022;8(2):187–201.

Schaefer LM, Hazzard VM, Smith KE, Johnson CA, Cao L, Crosby RD, et al. Examining the roles of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity in the relationship between psychological trauma and substance abuse among women with bulimic-spectrum pathology. Eat Disord. 2021;29(3):276–91.

Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: positive and negative urgency. Personality Individ Differ. 2007;43(4):839–50.

Atkinson EA, Miller LA, Smith GT. Maladaptive emotion socialization as a risk factor for the development of negative urgency and subsequent problem drinking. Alcohol Alcohol. 2022;57(6):749–54.

Brown S, Fite PJ, Bortolato M. The mediating role of impulsivity in the associations between child maltreatment types and past month substance use. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;128:105591.

Espeleta HC, Brett EI, Ridings LE, Leavens EL, Mullins LL. Childhood adversity and adult health-risk behaviors: examining the roles of emotion dysregulation and urgency. Child Abus Negl. 2018;82:92–101.

• Otten R, Mun CJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN, Dishion TJ. A developmental cascade model for early adolescent-onset substance use: the role of early childhood stress. Addiction. 2019;114(2):326–34. A longitudinal adolescent study examining the development of generalized impulsivity after childhood ATEs, and their relationship to adolescent substance use.

Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22(3):491–5.

Kalpidou M, Volungis AM, Bates C. Mediators between adversity and well-being of college students. J Adult Dev. 2021;29(1):16–28.

Trossman R, Mielke JG, McAuley T. Global executive dysfunction, not core executive skills, mediate the relationship between adversity exposure and later health in undergraduate students. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2022;29(3):405–11.

• De Bellis MD, Morey RA, Nooner KB, Woolley DP, Haswell CC, Hooper SR. A pilot study of neurocognitive function and brain structures in adolescents with alcohol use disorders: does maltreatment history matter? Child Maltreat. 2019;24(4):374–88. A longitudinal study examining brain function in adolescents with and without childhood ATEs, choice impulsivity, and related substance use.

Soon E, Siffredi V, Anderson PJ, Anderson VA, McIlroy A, Leventer RJ, Wood AG, Spencer-Smith MM. Inhibitory control in children with agenesis of the corpus callosum compared with typically developing children. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2024;30(1):18–26.

Ainslie G. Specious reward: a behavioral theory of impulsiveness and impulse control. Psychol Bull. 1975;82(4):463–96.

Acheson A, Vincent AS, Cohoon A, Lovallo WR. Early life adversity and increased delay discounting: findings from the Family Health Patterns project. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;27(2):153–9.

Oshri A, Liu S, Duprey EB, MacKillop J. Child maltreatment, delayed reward discounting, and alcohol and other drug use problems: the moderating role of heart rate variability. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2018;42(10):2033–46.

Kim-Spoon J, Lauharatanahirun N, Peviani K, Brieant A, Deater-Deckard K, Bickel WK, et al. Longitudinal pathways linking family risk, neural risk processing, delay discounting, and adolescent substance use. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(6):655–64.

•• Elton A, Allen JH, Yorke M, Khan F, Xu P, Boettiger CA. Sex moderates family history of alcohol use disorder and childhood maltreatment effects on an fMRI stop-signal task. Hum Brain Mapp. 2023;44(6):2436–50. A longitudinal study examining the relationship among childhood ATEs, multiple domains of impulsivity, and high-risk alcohol use in college students.

•• Meyers J, McCutcheon VV, Pandey AK, Kamarajan C, Subbie S, Chorlian D, et al. Early sexual trauma exposure and neural response inhibition in adolescence and young adults: trajectories of frontal theta oscillations during a go/no-go task. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(2):242-55.e2. A longitudinal study examining the relationship among childhood ATEs, multiple domains of impulsivity, and high-risk alcohol use in a college-aged sample.

•• Kim HK, Bruce J. Role of risk taking and inhibitory control in alcohol use among maltreated adolescents and nonmaltreated adolescents. Child Maltreat. 2022;27(4):615–25. A longitudinal adolescent study examining the relationship among childhood ATEs, multiple domains of impulsivity, and their relationship to adolescent substance use.

•• Klaus K, Vaht M, Pennington K, Harro J. Interactive effects of DRD2 rs6277 polymorphism, environment and sex on impulsivity in a population-representative study. Behav Brain Res. 2021;403:113131. A longitudinal adolescent study examining the relationship among childhood ATEs, multiple domains of impulsivity, and their relationship to adolescent substance use.

• Levitt EE, Amlung MT, Gonzalez A, Oshri A, MacKillop J. Consistent evidence of indirect effects of impulsive delay discounting and negative urgency between childhood adversity and adult substance use in two samples. Psychopharmacology. 2021;238(7):2011–20. A cross-sectional study examining the relationship among childhood ATEs, all three domains of impulsivity, and substance use.

• Evans SM, Reed SC. Impulsivity and the effects of alcohol in women with a history of childhood sexual abuse: a pilot study. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;29(4):395–406. An experimental study examining the relationship among childhood ATEs, all three domains of impulsivity, and substance use.

• Junglen A, Hruska B, Jensen T, Boros A, Delahanty DL. Improving our understanding of the relationship between emotional abuse and substance use disorders: the mediating roles of negative urgency and posttraumatic stress disorder. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(9):1569–79. Two studies examining and comparing the relationships among generalized impulsivity and substance use with childhood ATEs and lifetime ATEs.

Mullet N, Hawkins LG, Tuliao AP, Snyder H, Holyoak D, McGuire KC, et al. Early trauma and later sexual victimization in college women: a multiple mediation examination of alexithymia, impulsivity, and alcohol use. J Interpersonal Violence. 2022;37(19–20):NP18194–214.

McMullin SD, Shields GS, Slavich GM, Buchanan TW. Cumulative lifetime stress exposure predicts greater impulsivity and addictive behaviors. J Health Psychol. 2021;26(14):2921–36.

Pebole MM, Lyons RC, Gobin RL. Correlates and consequences of emotion regulation difficulties among OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2022;14(2):326–35.

Hawn SE, Chowdhury N, Kevorkian S, Sheth D, Brown RC, Berenz E, et al. Examination of the effects of impulsivity and risk-taking propensity on alcohol use in OEF/OIF/OND Veterans. J Mil Veteran Fam Health. 2019;5(2):88–99.

Brown RC, Mortensen J, Hawn SE, Bountress K, Chowdhury N, Kevorkian S, et al. Drinking patterns of post-deployment Veterans: the role of personality, negative urgency, and posttraumatic stress. Mil Psychol. 2021;33(4):240–9.

Mahoney CT, Cole HE, Gilbar O, Taft CT. The role of impulsivity in the association between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity and substance use in male military veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(3):296–306.

Bartlett BA, Smith LJ, Lebeaut A, Tran JK, Vujanovic AA. PTSD symptom severity and impulsivity among firefighters: associations with alcohol use. Psychiatry Res. 2019;278:315–23.

Black AC, Cooney NL, Sartor CE, Arias AJ, Rosen MI. Impulsivity interacts with momentary PTSD symptom worsening to predict alcohol use in male veterans. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(5):524–31.

Levy HC, Wanklyn SG, Voluse AC, Connolly KM. Distress tolerance but not impulsivity predicts outcome in concurrent treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. Mil Psychol. 2018;30(4):370–9.

Hallihan H, Bing-Canar H, Paltell K, Berenz EC. Negative urgency, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol risk in college students. Addict Behav Rep. 2023;17:100480.

Hofman NL, Simons RM, Simons JS, Hahn AM. The role of emotion regulation in the relationship between trauma and health-related outcomes. J Loss Trauma. 2019;24(3):197–212.

Santos LL, Netto LR, Cavalcanti-Ribeiro P, Pereira JL, Souza-Marques B, Argolo F, et al. Drugs age-of-onset as a signal of later post-traumatic stress disorder: Bayesian analysis of a census protocol. Addict Behav. 2022;125:107131.

Walker J, Bountress KE, Calhoun CD, Metzger IW, Adams Z, Amstadter A, et al. Impulsivity and comorbid PTSD and binge drinking. J Dual Diagn. 2018;14(2):89–95.

Esterman M, Fortenbaugh FC, Pierce ME, Fonda JR, DeGutis J, Milberg W, et al. Trauma-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions are uniquely associated with sustained attention dysfunction. Neuropsychology. 2019;33(5):711–24.

Morris VL, Huffman LG, Naish KR, Holshausen K, Oshri A, McKinnon M, et al. Impulsivity as a mediating factor in the association between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and substance use. Psychol Trauma: Theory Res Pract Pol. 2020;12(6):659–68.

Smyth JM, Hockemeyer JR, Heron KE, Wonderlich SA, Pennebaker JW. Prevalence, type, disclosure, and severity of adverse life events in college students. J Am Coll Health. 2008;57(1):69–76.

Wilson J, Jones M, Hull L, Hotopf M, Wessely S, Rona RJ. Does prior psychological health influence recall of military experiences? A prospective study. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(4):385–93.

Boals A, Contractor AA, Blumenthal H. The utility of college student samples in research on trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a critical review. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;73:102235.

Taber-Thomas B, Pérez-Edgar K. Emerging adulthood brain development. The Oxford handbook of emerging adulthood. 2015;126–41.

Banyard VL, Cantor EN. Adjustment to college among trauma survivors: an exploratory study of resilience. J Coll Stud Dev. 2004;45(2):207–21.

Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(5):748–66.

Hamilton KR, Mitchell MR, Wing VC, Balodis IM, Bickel WK, Fillmore M, et al. Choice impulsivity: definitions, measurement issues, and clinical implications. Personal Disord. 2015;6(2):182–98.

Jones A, Tiplady B, Houben K, Nederkoorn C, Field M. Do daily fluctuations in inhibitory control predict alcohol consumption? An ecological momentary assessment study. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235(5):1487–96.

Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: the brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(7):1180–9.

Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58(1):593–614.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Northeastern University Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W., N.F., and R.L. contributed to the conceptual idea of the manuscript, including inclusion and exclusion criteria. S.W. conducted the literature search, selection, and synthesis. K.G. conducted a secondary check of the search criteria and selected articles in accordance with inclusion/exclusion criteria. S.W. wrote the main manuscript text and completed the tables and figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided in-depth edits and feedback throughout multiple rounds of revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, S.E., Garcia, K., Fava, N.M. et al. Examining the Relationships Among Adverse Experiences, Impulsivity, and Alcohol Use: A Scoping Review of Recent Literature. Curr Addict Rep 11, 210–228 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-024-00552-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-024-00552-4