Abstract

Background

Dense Bone Islands (DBIs) are anatomic variants defined as radiopaque lesions consisting of hamartomatous cortical bone, often presenting as incidental radiographic findings. DBIs can also be known as idiopathic osteosclerosis, bone whorl, focal periapical osteopetrosis, bone scar and enostosis. We found a paucity of literature for management and reporting of this condition in children. For this reason, the authors describe sixteen cases of children and adolescents with dense bony islands and suggest a pathway for management.

Case series

Cases presented to the RNENT and Eastman Dental Hospital or private practice, either as chance findings or for diagnosis and treatment planning of undiagnosed radiopaque areas. The individuals were aged between 10 and 17 years; 6 boys and 10 girls. All radiographic reports described DBIs. Diagnoses were confirmed by a Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology Consultant and advised no intervention. In some cases, monitoring was advised. Caution in orthodontic tooth movement was advised for five patients.

Conclusion

DBIs are common findings that seldom require treatment; however, caution should be exercised when undertaking orthodontic movement in the area of a DBI due to a potential risk of root resorption. Accurate identification and multidisciplinary management are of utmost importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dense Bone Islands (DBIs) are anatomic variants defined as radiopaque lesions consisting of hamartomatous cortical bone, often presenting as incidental radiographic findings. DBIs can also be known as idiopathic osteosclerosis, bone whorl, focal periapical osteopetrosis, bone scar and enostosis (Yonetsu et al. 1997). These lesions are thought to be the result of failure of resorption during endochondral ossification and are thought to be congenital or developmental (Diab et al. 2014). Histologically, DBIs can be described as dense calcified tissue without marrow space or inflammatory cell infiltration (Eversole et al. 1984). The lesions can be found in the whole body, with preference for long bones. They are more common in adults, with no gender preference. Dense bone islands of the jaws are considered idiopathic, typically present as asymptomatic incidental findings, with no intra-oral manifestations and no bony expansion. DBIs may vary in size, outline, shape and density. Prevalence of DBIs ranges between 1.7 and 5.4%, with the mandibular molar and premolar regions more frequently affected (Marmary and Kutiner 1986; Petrikowski and Peters 1997). The lesion may increase in size and may complicate orthodontic treatment or implant placement. Differential diagnosis includes periapical cemental dysplasia, osteoma, complex odontoma, cementoblastoma, osteoblastoma and hypercementosis (McDonnell 1993).

We found a paucity of literature for management and reporting of this condition in children. For this reason, the authors describe sixteen cases of children and adolescents with dense bony islands and suggest a pathway for management.

Case series

Cases presented to the RNENT and Eastman Dental Hospital or private practice, either as chance findings or for diagnosis and treatment planning of undiagnosed radiopaque areas. The individuals were aged between 10 and 17 years; 6 boys and 10 girls. All radiographic reports described DBIs (Table 1).

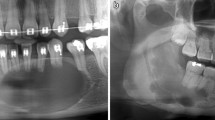

Most cases were unilateral and located in the body of mandible: Five in the lower right quadrant (Fig. 4) and seven in the lower left quadrant (Figs. 2 and 3). One case had a DBI in the maxillary alveolus (Fig. 1). DBIs measured between 1.5 and 13 mm. Interestingly, one patient (case 1) had a diagnosis of dentinogenesis imperfecta, another patient was in remission for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, while the other patients were referred to specialist care for caries. None of the patients were symptomatic at assessment (Figs. 2, 3 and 4).

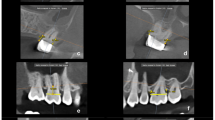

Three patients were referred by an orthodontist or a general dental practitioner, prior to orthodontic treatment (cases 3, 9 and 12). Two patients had ongoing (case 2) or completed orthodontic treatment (case 4). Six cases were chance radiographic findings (cases 6, 7, 9, 11, 13 and 14) and three cases were referred for management of the radiopaque areas (cases 1, 5 and 8). None of the cases had evidence of resorption of adjacent teeth (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9).

Case 10 was referred for specialist radiology opinion following mid-orthodontic treatment in primary care. Resorption of the mesial root of LR6 was noted in close proximity to a dense bone island (Fig. 10a, b). Monitoring of LR6 was advised (Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14).

Case 15 (Fig. 15) had an extensive bone island that was probably responsible for the ectopic position of the LL3. Following multidisciplinary discussion, it was decided to extract LL3 and monitor the dense bone island.

Case 16 (Fig. 16) had a large bone island on the buccal aspect of the maxillary alveolar process, occupying at least 50% of the alveolar process between UR3 and UR2 and extending to the right nasal fossa. In this case, following multidisciplinary discussion, orthodontic treatment was deemed contra-indicated in the area of the dense bone island.

Diagnoses were confirmed by a Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology Consultant and advised no intervention. In some cases, monitoring was advised. Caution in orthodontic tooth movement was advised for five patients (cases 2, 3 5, 12 and 16), with orthodontic tooth movement in the area of the dense bone island being contraindicated due to increased risk of resorption of adjacent tooth roots.

Discussion

Most DBI lesions are discovered incidentally during routine radiographic examination. The size of the lesions is usually stable, with rare reports discussing potential for enlargement (Greenspan and Stadalnik 1995; Petrikowski and Peters 1997; Mariani et al. 2008). Nakano et al. in 2002 found a 7% increase in size of a DBI on a 10-year-old girl. This is in agreement with Petrikowski and Peters’ conclusion for children and teenagers that about 40% of DBIs are thought to increase in size a period of 10 years and about 17% decrease in size for the same period. It is thought that this increase in size accompanies normal bone growth. In our case series, we found no size changes during our follow-up times. In the absence of agreed guidelines, the authors suggest adoption other authors’ advice that the lesion is monitored at least until the patient’s growth is completed and the lesion has stopped evolving (Nakano et al. 2002).

Although DBIs are often of no clinical significance, dental extraction of a tooth embedded into a DBI may result in an infected socket and pain of the edentulous area (Marmary and Kutiner 1986). In this case series, however, none of these findings was noted as no extractions were undertaken in close proximity to a DBI. We found one case report of an implant placed in close proximity to a dense bone island. The authors resourced to CBCT imaging and advised extreme care in planning as well as increased period of follow-up post operatively (Li et al. 2016).

Two case reports found symptoms related to dense bone islands present in the femur and in the tibia of a 10 and a 69-year-old, respectively. In these cases, DBIs were managed with excision followed by histology (Greenspan et al. 1991; Diab et al. 2014). One paper report on neuropathy related with compression of the inferior dental nerve due to the presence of a DBI (Debevc et al. 2017). Although none of our patients reported any DBI-related symptoms, the authors recommend timely diagnosis and accurate treatment planning for DBIs.

Medically, DBIs are of little clinical significance; however, a differential diagnosis should be established to rule out osteoblastic metastases from a known primary tumor (Nakano et al. 2002). Although DBIs are histologically different to osteomas, it is important to consider these as differential diagnoses as these may be associated with adenomatous intestinal polyps which may suffer malignant transformations (Butler et al. 2005, Sinnott and Hodges 2020). Multiple DBIs, with or without associated osteomas, may be a feature of Gardner’s syndrome (Davies 1970). Suspected medical findings must be discussed with the patient’s medical practitioner.

This case series reports sixteen cases of DBIs. All cases required multidisciplinary management, with radiology assessment and reporting for diagnosis. Three patients had initiated or completed orthodontic treatment prior to diagnosis of DBI, two with no unfavorable outcomes to adjacent teeth. In other cases, caution was advised for orthodontic tooth movement in the proximity of the DBI. Liaison with orthodontic colleagues was undertaken in these cases. The remainder of patients required no further investigations or treatment, other than monitoring. However, one patient (case 10) was referred for an opinion mid-treatment, after root resorption had occurred. The presence of DBIs offers additional challenges for orthodontic treatment, including difficulty with achieving space closure and adequate root tip or torque (Sinnott and Hodges 2020). Due to these challenges, and the possibility of iatrogenic root resorption in relation to a DBI, care is recommended when planning orthodontic interventions.

Sinnott and Hodges (2020) suggest that CBCT may be beneficial to ascertain the full extent of the lesion. In this case report, a DBI seemingly measuring 6 mm on a periapical radiograph was found to be significantly larger (24 mm). In our case series, two patients were found to benefit from CBCT prior to orthodontic planning.

Following revision of the literature and findings from our case series, a management flowchart is proposed to aid in treatment planning of DBIs (Fig. 17). These findings include the need to monitor the lesion and request radiographic report when required. In addition, if orthodontic treatment or implant placement is required, care must be taken especially if the DBI is in close proximity to the roots or implant.

Conclusion

DBIs are common findings that seldom require treatment; however, caution should be exercised when undertaking orthodontic movement in the area of a DBI due to a potential risk of root resorption. Accurate identification and multidisciplinary management are of utmost importance. Monitoring size changes is recommended until completion of patient’s growth.

References:

Butler J, Healy C, Toner M, Flint S. Gardner syndrome—review and report of a case. Oral Oncol Extra. 2005;41:89–92.

Davies A. Gardner’s syndrome—a case report. Br J Oral Surg. 1970;8:51–7.

Debevc D, Hitij T, Kansky A. Painful neuropathy caused by compression of the inferior alveolar nerve by focal osteosclerotic lesion of the mandible: a case report. Quintessence Int. 2017;48:725–32.

Diab MG, Glard Y, Launay F, Jouve JL, Bollini G, Cottalorda J. Small bone islands: unusual clinical symptomatology. Orthop. 2014;37:e79–82.

Eversole L, Stone C, Strub D. Focal sclerosing osteomyelitis/focal periapical osteopetrosis: radiographic patterns. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:456–60.

Greenspan A, Stadalnik R. Bone island: scintigraphic findings and their clinical application. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1995;46:368–79.

Greenspan A, Steiner G, Knutzon R. Bone island (enostosis): clinical significance and radiologic and pathologic correlations. Skelet Radiol. 1991;20:85–90.

Li Z-J, Lai R-F, Feng Z-Q, Li Z-J, Lai R-F, Feng Z-Q. Case history report: cone beam computed tomography for implant insertion guidance in the presence of a dense bone island. Int J Prosthodont. 2016;29:186–7.

Mariani G, Favaretti F, Lamazza L, de Biase A. Dense bone island of the jaw: a case report. Oral Implantol. 2008;1:87.

Marmary Y, Kutiner G. A radiographic survey of periapical jawbone lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:405–8.

Mcdonnell D. Dense bone island: a review of 107 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:124–8.

Nakano K, Ogawa T, Sobue S, Ooshima T. Dense bone island: clinical features and possible complications. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12:433–7.

Petrikowski CG, Peters E. Longitudinal radiographic assessment of dense bone islands of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:627–34.

Sinnott PM, Hodges S. An incidental dense bone island: a review of potential medical and orthodontic implications of dense bone islands and case report. J Orthod. 2020;47(3):251–6.

Yonetsu K, Yuasa K, Kanda S. Idiopathic osteosclerosis of the jaws: panoramic radiographic and computed tomographic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:517–21.

Acknowledgement

Dawood and Tanner, Specialist Dental Practice, London.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alfahad, S., Alostad, M., Dunkley, S. et al. Dense bone islands in pediatric patients: a case series study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 22, 751–757 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40368-020-00596-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40368-020-00596-w