Abstract

The internet has broadened the communication of digitized journals and books among scholars and the perception that academic commercial publishers use copyright law to restrict the free circulation of scientific knowledge. Open access is changing the business model of academic publishing to the extent that copyright law is increasingly being viewed as needing to be balanced against the right to benefit from science. Some have called for copyright law to be revised to promote open access to academic publishing. The question of just how copyright law should be revised to achieve this is today more topical than ever. However, there is a need to clarify and question the role that copyright law should play and there is much to be gained from consideration of the role that competition law can play. Additionally, initiatives to implement open access have been taken by stakeholders (academic authors, publishers, universities, libraries, and research funding agencies) such as open access policies and the new “read and publish” agreements between publishers and universities’ libraries. But the transition towards sustainable universal open access will be a long, complex process since the interaction between these stakeholders can lead to conflicts of interest. This article also evaluates these initiatives and suggests the best approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Progress in science benefits society; yet new findings in scientific research – published in books, articles, conference papers and presentations – are copyright protected. As such, copyright can be seen as the instrument publishers use to exercise control over the circulation of knowledge, enabling them to prevent access to scholarly publications. Indeed, it has been pointed out that, by limiting the ability to share published scientific knowledge, this prevailing restricted-access dissemination model inhibits the emergence of a truly global and collaborative scientific community.Footnote 1

The open access (OA) paradigm that has emerged with the advent of the internet is a reaction against this model. As one of the leading proponents of OA stresses, open access literature is “digital, online, free of charge, and free of most copyright and licensing restrictions”.Footnote 2 Nonetheless, OA is not antithetical to copyright: in fact, OA publishing is based on copyright licenses granted by scholars. The authors themselves lift the barriers imposed by copyright and agree to publish the output of their research and to disseminate their findings with the sole restriction that their authorship be mentioned and any commercial uses be impeded. Thus, OA is enabled by copyright.Footnote 3

Importantly, in the case of OA literature, authors are unpaid, yet publishers claim a fee to publish their articles and books in OA – the so-called “article processing charge” (APC) or “book processing charge” (BPC) that allows publishers to recoup the costs incurred in improving the quality of the article or book and processing it in a publishable form. In this sense, publishers address OA publishing as a new business model, in which APCs and BPCs are substitutes for subscription license payments and book sales. No remuneration of authors is contemplated in APCs or BPCs.

OA to scholarly publishing is also feasible without paying publishers’ processing charges if the pre-print version of paywall publications is made publicly available in institutional repositories (so-called green OA). Indeed, the EU and some national research bodies have implemented measures to ensure that scholarly publications resulting from their funding are made publicly available in public depositories immediately upon publication.Footnote 4 However, publishers claim that embargo-free green OA is not financially sustainable, since it threatens their subscription business model and undermines their potential support for OA journals based on APCs.Footnote 5 Hence, it is evident that publishers will only agree to OA publishing if they can find a sustainable business model to achieve it at scale. Therefore, any claim that copyright is the main obstacle to the implementation of OA is highly questionable. Despite this, many voices call for amendments to copyright law to facilitate OA to scholarly publishing.

This paper seeks to examine the implications of copyright for OA to scholarly publishing. First, it considers the extent to which copyright constitutes a barrier to scientific knowledge, and whether the right to benefit from science and culture justifies mandatory OA to scholarly publishing or rather requires an adjustment to copyright law. Second, this paper analyses the copyright issues and challenges associated with different initiatives to foster OA, including open access policies, amendments to copyright legislation, and the new read and publish agreements between publishers and research institutions. Finally, the economic and competition law issues that arise in relation to OA publishing are examined.

2 Copyright as a Barrier to Scientific Advancement

The shift from analog to digital publications has increased the perception that copyright protection of scientific works impedes access to knowledge that should be free. However, as stressed in the Introduction of this article, the OA movement does not oppose copyright protection of scientific publishing: what the leading voices of the OA movement claim is that copyright on research articles traditionally protected publishers, not authors,Footnote 6 and that copyright is being used by some publishers to keep their business profitable.Footnote 7

The academic publishing market has been characterized by a number of long-standing disruptions: many researchers agree to publish their contributions in journals (and even in books) without any remuneration. Academics view scholarly publishing as a means of facilitating the dissemination of their research and building a reputation, both by publishing in high impact factor journals and via the system of citations.Footnote 8 For this reason, it has been argued that conventional copyright rationale does not serve as an economic incentive for researchers and should be abolished for academic works.Footnote 9 However, such a view is open to debate. The fact that most academic authors do not share in the publishers’ profits does not justify depriving them of the right to claim copyright royalties from publishers. Nor does it affect the role and function of copyright. As discussed, the view that academic authors spurn the idea of making money from the use of copyright works for research and education, being satisfied with the enhancement to their reputation and funding opportunities, may be philosophically sound, but is contractually anomalous.Footnote 10

Criticism has also been expressed of the limited concern shown by copyright law for the scientific perspective, as well as the weak research exceptions to copyright exclusive rights and the general trend towards broadening copyright protection – all elements that conspire against freedom to access and exchange information, disseminate knowledge, and preserve research results.Footnote 11 The recent COVID-19 pandemic served to highlight the right to science together with the urgent need to address a new copyright regime.Footnote 12 Copyright laws are said to act like a lock on the open circulation of research and scholarship. They fail to serve their original purpose of promoting science in the digital era.Footnote 13 Some authors contend that reconceptualizing copyright in relation to research activities can provide powerful arguments for substantive changes in copyright law;Footnote 14hence, the question of the most suitable copyright design for academic works is today more topical than ever.Footnote 15

Before assessing whether copyright law should be amended or even abolished in the case of scholarly publishing, so as to guarantee access to scientific knowledge, it is necessary, first, to consider the scope of the right “to benefit from science” and its legal implications for access to academic publishing and, second, to assess how copyright might act as a barrier to scientific knowledge.

2.1 The Right to Benefit from Science

To date, the right to benefit from science has been inadequately discussed, despite being recognized, with a variety of different wording, in instruments of human rights. In fact, some scientists describe this right as “obscure” and its interpretation as “neglected” to the point that few are aware of its existence.Footnote 16

The right to enjoy the benefits of science has traditionally been invoked as a counterweight to the expansion of intellectual property (above all patents), whereas the “right to participate in culture” is seen as articulating a series of values that limit copyright.Footnote 17 Yet, copyright protects scientific works and, as such, can impede access to research findings.

2.1.1 Scope of the Right to Benefit from Science

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted by the United Nations in 1948, was the first international legal instrument to recognize the fundamental right to “share in scientific advancement and its benefits”, along with cultural rights and the protection of authors’ rights (Art. 27 UDHR).Footnote 18 The drafting history of Art. 27 shows that the inclusion of individual author’s and inventor’s rights in an article on public rights of access to science was strongly debated, but that the primary concern was that the protection of these individual rights should not cut across the public good of facilitating access to knowledge, culture, and science, whether for liberal, utilitarian, or communitarian reasons.Footnote 19

Almost twenty years later, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), adopted by the United Nations in 1966, recognized the right of everyone to “enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications”, after recognizing the right to “take part in cultural life”, while guaranteeing the protection of intellectual property (Art. 15.1).Footnote 20 In the travaux préparatoires of the ICESCR, some countries objected to incorporating the provision on intellectual property on the grounds that everyone’s right to benefit from science and participate in culture should not be intermixed with property rights.Footnote 21 However, it was argued that the three rights were substantively interrelated, each being instrumental to the realization of the others. The rights of authors and scientists to prevent others from altering their creations were understood to be essential preconditions for cultural freedom and participation and scientific progress.Footnote 22

In the case of the UDHR, the wording of the right to benefit from science has been described as being more akin to that of a freedom than a positive right that states must enable.Footnote 23 In contrast, the ICESCR sets out specific obligations incumbent upon states for guaranteeing the right to benefit from science, such as taking the steps necessary for “the conservation, the development, and the diffusion of science” (Art. 15.2).Footnote 24 Indeed, today, there is a growing consensus that the core content of the right to benefit from science in the ICESCR includes an obligation on states to enable access to scientific information.Footnote 25

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) (1950) does not include any provision on the right to benefit from science; rather the right is understood as a form of collective freedom of expression: Art. 10 talks of the freedom to “receive and impart information and ideas without interference”. As such, the states’ obligations are negative and limited to not interfering with this freedom, rather than requiring a proactive realization of the right to benefit from science.Footnote 26

Regarding academic freedom, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000) recognizes scientific research as the scientist’s autonomy to conduct research: Article 13 states that “[t]he arts and scientific research shall be free of constraint. Academic freedom shall be respected”. Accordingly, in the case of Commission v. Hungary, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) declared that “academic freedom in research […] should guarantee freedom of expression and of action, freedom to disseminate information and freedom to conduct research and to distribute knowledge and truth without restriction”.Footnote 27

Thus, it seems that international recognition of the right to benefit from science and the right to conduct research free of any constraints contained in human rights instruments cannot be considered as granting researchers individual rights to access scientific output, but rather as obliging states to protect science as a public good. For instance, Art. 44 of the Spanish Constitution (1978) provides that culture and science and scientific research be promoted by public authorities. Yet, some authors argue that a new fundamental right to research is derived from the interplay between the right to benefit from science (as recognized under the UDHR and the ICESCR), freedom of expression and academic freedom, in combination with the European Union’s aims and objectives regarding sustainability and technological advancement.Footnote 28 According to these authors, the fundamental right to research enables access to information to conduct research.Footnote 29 This opinion is supported by those who believe that EU legislation is under an obligation to create a more favourable, enabling environment for scientific research.Footnote 30

But what are we supposed to understand by the argument that the right to benefit from science should enable access to information to facilitate research? Does this imply that access to scientific publications should be free and without copyright restrictions?

2.1.2 The Right to Benefit from Science, and Access to Scientific Publishing

The United Nations, in its legal instrument, appears to explicitly link science and technology with human rights, considering such ties beneficial to human lives.Footnote 31 As such, it could be argued that the right to benefit from science justifies mandatory OA only in the case of research publications that contribute to human well-being and better life conditions. But it might also be concluded that OA should be mandatory for scholarly publishing across the board, since all journal articles are scientific, regardless of their area of knowledge.

How can scientific publications be defined? Neither the UDHR nor the ICESCR chooses to define what science is. The Venice Statement on the Right to Enjoy the Benefits of Scientific Progress and its Applications, adopted by experts convened by UNESCO in 2009, declares that the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress is applicable to all fields of science,Footnote 32 where science is deemed, among other things, an instrument for “advancing knowledge of a specific subject matter” and “procuring a set of data and testing hypotheses that may be useful for some practical purpose”.Footnote 33

Indeed, science can be distinguished from other domains of culture and knowledge by its progressive nature.Footnote 34 The natural sciences, as well as the human and social sciences, including history and economics, also advance thanks to research findings based on procuring sets of data and testing hypotheses. Since the first journals with a specific orientation emerged in 1870, scientific publications have been defined according to a methodology that meets the following conditions: identification of the problem tackled in the publication, sequential development of the argument, description of the methods used, presentation of empirical evidence, obligatory links – using citations – to earlier communications by other scientists, and admissibility of presenting speculative thought.Footnote 35 This methodology has been adopted by all academic journals regardless of their area of specialization (be it the natural sciences, philosophy, or even law). Thus, the right to benefit from science might be expanded to all scholarly publications, as all of them can be considered scientific.

Yet, to argue that the right to enjoy the benefits of science means states should be obliged to impose mandatory OA on scientific publishing does not seem entirely admissible. The UNESCO Draft Recommendation on Open Science (November 2021)Footnote 36 identifies a set of actions whereby Member States can promote OA infrastructure, including journals and OA publication platforms, repositories and archives. According to the Recommendation, mandatory OA is only required in the case of research promoted by public funding.Footnote 37 Thus, the right to benefit from science requires that states encourage, rather than actually impose, OA for all scientific publications.

2.2 Copyright Protection of Scientific Works

In 1907, Josef Kohler, the German jurist accredited with establishing the concept of rights to immaterial goods and laying the foundations for copyright in Germany and Europe, described scientific works protected by copyright as explanations of research findings and clarifications of their grounds.Footnote 38 For Kohler, scientific works were literary works that explained discoveries and research findings. But inasmuch as scientific works may also include figures, drawings, photographs and images describing these findings or elements of nature, they can also be considered plastic or artistic works, which – provided they are original – enjoy copyright protection. Other examples of scientific works protected by copyright include audiovisual works (such as documentaries explaining discoveries) and scientific databases.

Interestingly, participants at the 1883 conference organized by the Association Littéraire et Artistique International debated whether or not to include the term scientific in the title of the Berne Convention for Protection of Literary and Artistic Works adopted in 1886,Footnote 39 but deemed it irrelevant.Footnote 40 Nonetheless, Art. 2 of the Berne Convention states that the expression “literary and artistic” works shall include “every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever may be the mode or form of its expression”. However, the term scientific production does not refer to such things as scientific discoveries. The use of “literary, scientific and artistic” to qualify the productions protected by the Berne Convention derives from earlier bilateral conventions on copyright between Member States; as some scholars point out, the term should not be taken at face value.Footnote 41

Indeed, most European national copyright laws hold that the object of copyright protection is literary and artistic works, and make no mention of scientific works, although the latter are included in their illustrative lists of copyrighted works.Footnote 42 However, both German and Spanish Copyright Acts explicitly hold that copyright protects literary, scientific, and artistic works.Footnote 43 German commentators point out that any difference between these three categories is irrelevant in terms of law, since scientific works may also be literary or artistic works; what defines the category of scientific works is the subject matter.Footnote 44 Meanwhile, Spanish commentators describe scientific works as those that deal with scientific discoveries, theories, methods, and ideas, and note that their content is free, but the wording, images or figures created by the author to explain the content is copyright protected.Footnote 45

In short, scientific works are defined by their science-related content. However, they have a hybrid character, as their form contains elements of personal expression, and they constitute non-substitutable building blocks of information.Footnote 46 Research publications are an example of scientific works that are protected by copyright if they “reflect the author’s personality”.Footnote 47 But how does a researcher make free and creative choices in a scientific work? What part of a scientific article or book results from the author’s original creativity, if it deals with research findings and scientific information?

2.2.1 Author’s Creation versus Research Findings

As Kohler noted, a research finding is not the creation of an author but a “scientific truth”.Footnote 48 The Scottish philosopher Dugald Stewart, in distinguishing discovery from invention, remarked that the object of the former was “to bring to light something which did exist, but which was concealed from common observation”.Footnote 49 Research findings are, or should be, free because they result from obtaining, contrasting, and verifying empirical evidence about facts or truths that were previously unknown. For instance, if an article reports the risk factors for COVID-19 in inflammatory bowel disease, or new findings about Russian exiles in Spain between 1914 and 1920, the respective authors did not create the results obtained, but rather found evidence to demonstrate them. Yet, research findings were considered a possible object of intellectual property (in addition to patents and copyright) in discussions conducted at international level between the First and Second World Wars, although interest eventually declined and then completely dropped away with the advent of the global crisis.Footnote 50

In the case of contributions that count as authorial from the standpoint of science – such as research publications – the focus for copyright is on verbal expression, on the choice and ordering of words, rather than on the generation of data or ideas.Footnote 51 Consequently, copyright prevents copying of the original explanations used by a researcher when clarifying hypotheses or describing the procedures used and difficulties encountered when conducting the study, as well as of the final conclusions drawn in the publication. Likewise, copyright prevents copying of any original images, graphics or photographs created by the author to illustrate the processes, data, formulae, or elements related to the study’s theories, findings or discoveries. Conversely, those elements of a research publication that are not created by the author (i.e. data, empirical evidence, research processes, experiment results, formulae, elements of nature, etc.) are not copyright protected. They can therefore be copied, distributed, and further communicated to the public. As Art 9.2 of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) states: “Copyright protection shall extend to expressions and not to ideas, procedures, methods of operation or mathematical concepts as such”.

This leads to the conclusion that copyright does not protect the scientific information in research publications but rather the originality of the author in expounding the findings, data, hypotheses, or procedures. Originality is what authors give material form to and what justifies the granting of copyright,Footnote 52 whereas science is concerned with the empirical evidence. But creativity and science are not antithetical. The original explanations written by scientists, the conclusions they elaborate from the research conducted, or the images created to present their findings may also be relevant for scientific advancement, and help other researchers to understand their findings more fully, since they complement the information provided in the rest of the article or book. From this perspective, it can be argued that copyright does not put a lock on the scientific information contained in research publications but rather prevents copying of the content created by researchers when explaining or expounding their findings in their publications.

However, if scientific journals are included in databases, publishers may be entitled to prevent extraction of the scientific data contained in their journals under the sui generis right provided for in EU Directive 96/9/EC on the legal protection of databases.Footnote 53 This right is granted to a publisher if they can prove substantial investment in obtaining, verifying, or presenting the contents of a journal’s database. As a result, national legislators have limited the scope of copyright and the sui generis right by introducing certain exceptions, thereby allowing limited free use of scientific works and scientific data for research purposes.

2.2.2 The Adjustment of Copyright Law to Facilitate Research

To date, EU copyright law has recognized two main exceptions regarding science: the research exception, as introduced by the Information Society Directive (ISD) in 2001,Footnote 54 and the text and data mining exception for the purposes of scientific research, which was implemented by the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (DSMD) in 2019.Footnote 55 However, the scope of the ISD research exception is narrow, especially when applied to research publications, and the new text and data mining (TDM) exception of the DSMD raises a number of controversial legal questions.

Article 5(3)(a) ISD allows copyrighted content to be reproduced and communicated to the public for scientific research, solely for non-commercial purposes, as long as the source and the author’s name are indicated.Footnote 56 In the case of research publications, this exception is basically the equivalent of quotation. As has been noted, reproduction and extraction for scientific peer review and joint research are not necessarily exempt under national implementations of the somewhat vague Art. 5(3)(a) ISD;Footnote 57 indeed, some scholars argue that the scope of this exception should be broader.Footnote 58 Moreover, the ISD makes the research exception optional throughout the EU Member States when it ought to be mandatory and have the same scope to provide legal certainty to researchers across Europe.Footnote 59

By contrast, the new TDM exception for the purposes of scientific research, as laid down in Art. 3 DSMD, is mandatory throughout the EU. This new exception – where TDM is defined as “the automated processing […] of large volumes of text and data to uncover new knowledge or insights”Footnote 60 – can play an important role in research projects that require the extraction of data from protected literary and artistic works.Footnote 61 The exception allows universities and research institutes, acting on a not-for-profit basis, to reproduce and extract data from research publications to carry out TDM for scientific research; importantly, it requires that they have lawful access to content.Footnote 62 The EU Directive clarifies that “lawful access” to content may be provided by OA licenses or through contractual arrangements, such as subscriptions.Footnote 63

As noted, subscriptions to journal databases give publishers too much scope for limiting TDM initiatives by means of contracts or technical protection measures.Footnote 64 The TDM exception for scientific research implies that publishers should be unable to use their contractual powers and technical protection measures to limit researchers’ ability to engage in TDM by imposing restrictions on access and use of their database content in exchange for making this content available.Footnote 65

In conclusion, copyright law has already been adjusted to facilitate research but not to facilitate the transition to open access. Additionally, other legal initiatives to foster open access have been undertaken by the main stakeholders in scientific publishing.

3 Initiatives to Foster Open Access

Sustainable universal OA to scientific publishing would undoubtedly benefit the research community. However, the transition to OA is set to be long and complex, as the interests of research funders, authors, universities, and commercial publishers clash with each other. Indeed, the tensions between these different stakeholders are currently reflected in the opposing stances they adopt in relation to any transition to OA. Yet, various initiatives have been taken: funders, higher educational institutions (HEIs) and research centres are adopting OA policies; some European countries have recently recognized a new right for scholars to publish in OA; and publishers are transforming their subscription agreements with institutions and authors to facilitate OA publishing.

3.1 Open Access Policies of Funders and Research Institutions

National governments are under growing pressure to promote the OA of scientific publishing. In the UK, following publication of the Finch Report in 2012, OA has become government policy,Footnote 66 and UK research and innovation policy on OA has not permitted a publisher-requested delay or “embargo period” between the publication of an article and public access to that article in a public depository since 2022.Footnote 67 In the same year, the Spanish Science Law was amended, requiring researchers who benefit from public funding to deposit the manuscript version of their articles in a public repository at the time of publication.Footnote 68 The European CommissionFootnote 69 and cOAlition S, an international consortium of research funding organizations, recommend or impose OA policies to ensure that the research work they support is shared fully and immediately.Footnote 70 Universities and research centres are also adopting policies that impose OA mandates or right retention practices to make their researchers’ academic work immediately and openly available for scholarly communication.Footnote 71 Such policies are considered private instruments that have legal effectsFootnote 72 and raise certain legal issues.

3.1.1 OA Policies as “Mandates” to Researchers

Research funders make it compulsory for researchers who accept the terms and conditions of their funding to publish in OA. In such cases, OA is a legal duty for the researcher, and should they fail to comply with that obligation and publish articles in paywalled journals, the funder may take legal action against them.

In contrast, the OA policies adopted by certain universities and research centres can be considered more controversial. Some HEIs make OA mandatory, while others’ policies serve as mere recommendations or simply guidance for their academic staff.Footnote 73 It might be argued that OA mandates are justified if researchers are employees of public universities, and their research output is publicly funded.Footnote 74 Indeed, if researchers are employees of public or private HEIs, and publish works in the course of their employment, copyright may belong to their employers, which means these institutions may be legally entitled to impose OA mandates. However, universities and research centres do not usually claim copyright of their staff’s scientific scholarly work, given the nature of their employment and the freedom of research, a right that is constitutionally protected in some countries.Footnote 75

Some academics are critical of OA policies on the grounds that they threaten to inhibit scholarly publishing and, as a result, reduce an author’s academic freedom to publish in top journals.Footnote 76 Yet, as discussed, the right to decide on the commercial exploitation of research articles is not based on researchers’ academic freedom but rather on their intellectual property.Footnote 77 Copyright gives authors the freedom to decide whether or not they publish their scientific contributions, in which journal they wish to publish and whether or not they wish to make their work publicly available. For this reason, it has been noted that OA mandates imply appropriation of the researchers’ copyright.Footnote 78

Certainly, as long as HEIs and research centres are not copyright holders of their academic staff’s work, they are not entitled to impose OA mandates or right retention practices. They may, however, recommend that their staff comply with the funder’s OA mandates and encourage them to publish in OA or to make their pre-print publications available for scholarly communication.

3.1.2 Conflicts Between OA Policies and Authors’ Publishing Agreements

A relevant legal question arising in relation to OA policies is their effect on agreements entered into between researchers and publishers. Scholars complain that OA policies increase the administrative burden on them, as they are left to negotiate an increasingly complex copyright landscape with multiple interacting licenses.Footnote 79 Problems manifest themselves when a researcher assigns an exclusive license to a commercial publisher to use an article, but the same article is covered by a prior non-exclusive scholarly communications license granted by the author to the institution, resulting from the university’s OA policy. In such circumstances, is the publisher entitled to prevent the author from depositing the article in the repository and enforce an embargo?

The answer to this question is to be found in national legislation and needs to be considered from the perspectives of both copyright and contract law. According to some national copyright laws, a prior license granted by the author to the institution prevails over the exclusive license entered into later with the publisher. Section 33 of the German Copyright Act specifically regulates the effect of licenses granted subsequently on the same work. This provision is applied when there is conflict between subsequent licenses,Footnote 80 and implies that a prior non-exclusive license to use a work should prevail over an exclusive right on the same work granted later.Footnote 81 A similar rule is found in Art. 14.6 of the Spanish Copyright Act.Footnote 82 Indeed, various decisions of the Spanish Supreme Court have recognized that prior licenses should prevail if the author grants successive licenses on the same work.Footnote 83

Contract law is relevant for determining the liability of an author in such cases. By entering into an exclusive publishing license agreement, the author guarantees that the publisher retains the right to use the article, so the author does not come into conflict with the publisher’s business.Footnote 84 A prior non-exclusive license for scholarly communication will damage the publisher’s exploitation in the case of paywalled articles with an embargo. Clearly, publishers have no interest in publishing content that is already publicly available. Therefore, when entering into a publishing license agreement, the author has a legal duty to give notice to the publisher of any prior non-exclusive license with the institution.

Contract law protects the publisher that acts in good faith for valuable consideration and without having received notice of a prior non-exclusive license. According to UK legislation, in the case of exclusive copyright licenses, prior subsisting licenses are binding except for bona fide purchasers that did not receive notice.Footnote 85 In this case, UK legislation empowers the publisher with an exclusive right, which is deemed binding vis-à-vis any prior licenses. Therefore, if the publisher is not given notice of the prior license, it will be entitled to publish the article and expect the same outcome as if prior non-contractual licenses did not exist; thus, the publisher could prevent the university from using the article for scholarly communication until the embargo period expires. Moreover, the publisher could sue the author for breaking a warranty and claim the loss suffered as a result of not having been given notice of the prior license.Footnote 86 A breach of contract gives rise to action for damages, whether the term breached is a condition, a warranty, or an innominate term.Footnote 87 Thus, the publisher could claim the gain of which it had been deprived,Footnote 88 that is, the APC it would have charged if the article were published in OA.

For all these reasons, the publishers’ response to the growth and development of institutional OA polices based on rights retention has so far been limited and inconsistent.Footnote 89 Publishers see zero-embargo OA policies as undermining their gold OA business, and the largest commercial European publishers still impose embargoes on making self-archived publications openly available.Footnote 90

HEI and research centre policies may become an effective instrument for making academics aware of their responsibilities towards funders and of the advantages of making their research output publicly available. However, at the same time, HEIs and research centres need to respect the decisions that their academic staff make regarding OA publishing. The majority of academic authors still prefer to publish their articles in prestigious high-quality journals, regardless of the fact that they cannot make them publicly available.Footnote 91

3.2 Changes in Copyright Legislation

Some European countries recently adopted legislative initiatives to provide academic authors with a Secondary Publication Right (SPR), which enables them to make their published contributions publicly available on the condition that certain requirements are met. In 2013, Germany amended its copyright law, introducing the SPR in the section governing the transfer of author’s rights.Footnote 92 The same initiative was subsequently adopted by the Netherlands and Austria, which both amended their copyright laws in 2015.Footnote 93 In 2016, France recognized the SPR in its Code of Science Law,Footnote 94 and Belgium introduced it in its Code of Economic Law in 2018.Footnote 95 Despite marked differences between these five national iterations of the SPR, they all adhere to the same basic structure: (1) the secondary publishing right is only granted to authors of scientific contributions (published primarily in journals); (2) the research should be, at least partly, publicly funded; (3) the right only allows the author to make the “accepted manuscript” available to the public; and (4) an embargo period must be respected.Footnote 96 Finally, the SPR is unwaivable and inalienable, so the author retains this right, regardless of any transfer of rights to publishers, and cannot renounce it.

The SPR was first formulated by a German jurist as a moral right of academic authors; hence its inalienable nature.Footnote 97 However, it has been argued that the SPR is nothing more than a copyright limitation for publishers in disguise, with weak justifications, that would unduly prevent application of the three-step test to copyright limitations contained in Art. 13 TRIPS.Footnote 98 This article requires that copyright limitations or exceptions be limited to certain special cases that do not conflict with normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.

The embargo requirement to be met for exercising an SPR certainly looks like a copyright limitation. As observed, the basic idea underlying embargoes in copyright limitations is to ensure normal exploitation of a work.Footnote 99 The same idea underpins restricting the SPR to the “accepted manuscript”, that is to say the manuscript approved by the author for publication following peer review as opposed to the final typeset published version(“Version of Record”). The SPR takes sufficient account of the interests of scientific publishing firms,Footnote 100 which is a sign that national legislators formulated the SPR with a view to balancing researchers’ interests in publishing in OA with publishers’ investments.

Recognition of the SPR has not proved to be especially effective for the expansion of OA in those European countries that have adopted it. According to a 2021 study entitled “Open Access in Europe: a National and Regional Comparison”, the most “open” areas in Europe are the UK and the Scandinavian countries, owing to strong incentives from public agencies and the fact that several universities have adopted effective OA policies with dedicated staff and funds.Footnote 101

Harmonizing the SPR as a copyright exception or limitation at EU level has also been suggested.Footnote 102 However, this would be problematic because any legislative initiative to foster OA needs to balance all the interests at stake. If the SPR is formulated in such a way that it can only be exercised after an embargo, and it continues to be limited to “accepted manuscripts” to assure the publishers’ investment, the SPR is doomed to fail as a mechanism for expanding OA to scientific publishing. Embargoes frustrate researchers in their efforts at keeping up to date with the latest publications in their field; and researchers are not especially enthused by the use of their “accepted manuscript”,Footnote 103 because actual publication in a journal is critical for achieving a reliable, final, typeset, scholarly record.Footnote 104 Additionally, accepted manuscripts are deposited in vast institutional repositories that contain all kinds of academic output from the scholarly community (e.g. unpublished articles, conference papers, thesis, dissertations), which are not systematically organized and do not differentiate publications according to quality,Footnote 105 as a journal would normally do.

In short, copyright law is not the best instrument for fostering universal OA. When amending copyright law, the legislator must consider all the interests at stake: not only the concern of funders and researchers to expand access to scientific knowledge in the interests of society, but also the legitimate interest of publishers in profiting from their investments. In contrast, agreements between publishers and research institutions might provide a negotiated solution for the implementation of universal OA.

3.3 New “Read and Publish” Agreements

OA is also remodelling publishing agreements and changing the business of academic publishing. Subscription licenses, traditionally offered by publishers to universities or research institutions, to grant access to scientific journals, are being transformed into new “Read and Publish” (R&P) agreements or “transformative agreements” (TAs). By means of these R&P agreements, publishers grant universities the right to access, copy and download paywalled articles from their journals, and the right to publish a certain number of articles in their commercial journals in OA.

R&P agreements emerged as a result of a report published by the Max Planck Society Digital Library in 2015, which demonstrated that expenditure on subscriptions to scientific journals could be redirected and re-invested into OA business models to pay for APCs.Footnote 106 As such, these new agreements are not supposed to add APCs to subscription fees, but rather to gradually replace subscription income with that generated by APCs for OA publishing.Footnote 107 According to the ESAC Initiative (Efficiency and Standards for Article Charges), these new agreements will allow former subscription expenditure to be repurposed to support the OA publishing of the negotiating institutions’ authors, thereby gradually and definitively transforming the business model that underpins scholarly journal publishing from one based on toll access (subscription) to one in which publishers are paid a fair price for their OA publishing services.Footnote 108

The first R&P agreements were entered into between commercial publishers and institutions in 2018, and there has been a gradual increase in the number of agreements implemented since 2020.Footnote 109 Most have been signed between the major publishers (Elsevier, Wiley, Springer, Taylor & Francis, Walter de Gruyter, Cambridge University Press, Oxford University Press, etc.) and the libraries or consortia libraries of HEIs and research centres.

The primary innovation of R&P agreements lies in the clause referring to subscription fees and in the number of APCs included in the contract. Publishing fees are amalgamated with subscription fees, and depend on the number of researchers employed by an institution and the total number of articles they seek to publish in OA journals. For instance, the R&P agreement entered into between the Spanish National Research Council and Oxford University Press (OUP) in 2020 shows that the former will pay OUP almost EUR 1 million over five years to secure access to their journals and to publish 358 OA articles (with 24% of the fee corresponding to reading and 76% to publishing, and an APC of EUR 2,123 per article).Footnote 110 Although R&P agreements are not supposed to increase the cost of subscription licenses, they are associated with higher costs than traditional read-only subscriptions.Footnote 111 Additionally, in some cases, R&P agreements can result in overpayment (if the number of articles accepted for publication falls short of the agreed number) or under-availability (if some of the articles accepted for publication fall outside the bulk-sum payment and have to be covered separately).Footnote 112

R&P agreements also oblige “eligible authors”, whose articles are accepted for OA publication, to transfer their exclusive rights to publishers. Authors’ agreements are separately negotiated with the publishers.Footnote 113 Under these OA publishing agreements, the author grants the publisher an exclusive license, and the publisher states the Creative Commons License under which the article will be made publicly available.Footnote 114 The author receives no payment from the publisher, but the exclusive transfer of rights is justified as the article will be publicly available; hence, authors’ rights retention for scholarly communication is pointless.

Agreements between commercial publishers and institutions may be the best mechanism for providing a sustainable business model for OA, provided they rely on principles of party autonomy and contractual freedom. However, R&P agreements present the typical anomalies of contracts entered into between commercial publishers and HEIs or research centres. Commercial publishers impose high fees on these institutions to read and publish in OA, bundle all their journals into one single R&P agreement, and typically impose their own legal jurisdiction as the applicable law governing their contracts.Footnote 115 Determining which law applies to these agreements is a key issue, as US and UK copyright law tend to favour publishers’ commercial interests and permit the assignment of exclusive transfers of rights, whereas in civil jurisdictions the transfer of author’s rights is construed in favour of the author.Footnote 116

More importantly, the future of R&P agreements remains uncertain for publishers. If more institutions shift towards OA embedded in transformative agreements, the share of OA will dramatically increase. As a result, fewer research-oriented institutions will be tempted to cancel their subscriptions, reducing the journals’ income in the process.Footnote 117 The highest ranked universities will overpay APCsFootnote 118 compared to institutions with a lower publication output.Footnote 119 In the case of consortia, this behaviour may unbalance internal agreements on cost distribution.Footnote 120 Moreover R&P agreements will prove extremely challenging for smaller publishers and a few isolated journals.

4 Economic and Competition Law Issues Involved in Open Access Publishing

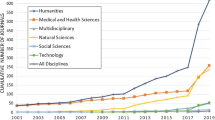

The journal publishing market is a complex, dynamic system, with journals constantly switching publishing houses, and publishing houses acquiring or merging with their competitors.Footnote 121 As a result of these dynamics, five big commercial publishers represent more than half the market for scholarly journals today.Footnote 122 These “big five” publish most of the high impact factor journals and, indeed, the majority of scientific papers.Footnote 123 This high degree of concentration of ownership of scientific journals has led to asymmetry in negotiating powers between research institutions and publishers. Thus, a publisher that owns a journal with a high impact factor enjoys a strong market position vis-à-vis not only researchers but also libraries.Footnote 124

The concentrated nature of the academic publishing market – including both OA and toll access journals – potentially offers top publishing companies a monopoly.Footnote 125 Indeed, in 2018, the European University Association (EUA) issued a statement expressing its concern about possible irregularities relating to pricing and market conditions in the research publishing sector. Their primary objections to the “big five” academic publishers were, first, their lack of transparency when pricing journal subscriptions and, second, their bundling of a large number of academic journals into one single agreement (a so-called “big deal”).Footnote 126

Academic publishers charge extremely high prices for subscriptions to individual journals, making it less attractive or nearly impossible to buy only the most interesting journals and skip the others. This means that libraries are left buying very large bundles, including journals that they might not actually be interested in. Additionally, the pricing structure for journal subscriptions and the fees for OA publishing remain quite obscure. The average APC for a journal article is, at present, USD 2,987, but there is tremendous variation in APCs across journals, which obviously cannot be explained by costs alone.Footnote 127 As OA publishing advances, subscriptions will gradually disappear, which suggests that APCs are being used by commercial publishers in lieu of subscription fees. If, eventually, universal OA is attained, subscriptions and book sales will cease and publishers will only charge once for publishing a scientific article or book in OA. However, as things currently stand, publishers’ income is based on thousands of subscriptions for the same journals and thousands of sales of the same book. Excessively high pricing of APCs and BPCs may become a potential risk in the OA publishing market.

Competition law may well have a key role to play in correcting the dominant practices of academic publishers in the publishing market. In the case of the EU market, Art. 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of European Union (TFEU) prohibits abuse by dominant firms, and Art. 102(a) TFEU lists as examples of abusive conduct “directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase or selling prices or other unfair trading conditions”. Importantly, Art. 102 TFEU applies when one undertaking has a “dominant” position or where two or more undertakings are “collectively dominant”.Footnote 128 This could be considered the case of the “big five” commercial publishers that account for more than 50% of the market share for scholarly journals.

Difficulties may be encountered when seeking to determine whether the largest commercial academic publishers are indeed collectively abusing a dominant market position. According to the CJEU’s decision in the case of Compagnie Maritime Belge Transports and Others v. Commission, a finding that two or more undertakings hold a collective dominant position must, in principle, “proceed upon an economic assessment of the position on the relevant market of the undertakings concerned”.Footnote 129 Thus, the first step in ascertaining whether an undertaking or group of undertakings exercises a dominant position is to define the relevant market in which they compete. According to the EU Commission, obtaining this definition requires defining both the product market and the geographic markets, where the relevant product market comprises all products or services regarded as interchangeable or substitutable by the consumer by reason of their characteristics, prices and intended use.Footnote 130 In the case of academic publishers, the relevant market might be deemed to comprise the publishing market of academic journals and periodicals. However, this is highly controversial, because if the product market is drawn narrowly, with relatively few competing products, it is much more likely that an undertaking will be found to be dominant.Footnote 131 As for the geographic market, this is not readily defined for commercial scientific publishers, given that the large publishing houses have been transformed into digital platforms with multi-sided markets.Footnote 132

Yet, as discussed, an excessive pricing ruling is possible in any market, not only where firms abuse their dominant market positions.Footnote 133 Excessive pricing and bundling can also be considered a reflection of the publishers’ control over the agreements entered into with research institutions. Thus, at what point can a price be deemed excessive? There is no single adequate method for evaluating an excessive price, but cost-benefit balancing tests may help to chart the interface of competition and intellectual property for a particular commercial practice.Footnote 134 Furthermore, the CJEU has ruled that a price can be “objectively” determined excessive by “making a comparison between the selling price of the product in question and its cost of production, which would disclose the amount of the profit margin”.Footnote 135

However, the current lack of transparency on the part of publishers regarding their article publishing costs hinders any assessment as to whether their costs and profits are well balanced. In the past, publishers had to invest in technology to transform articles and books into publishable forms and guarantee the print distribution, but digital publishing technologies have reduced such costs, especially in the case of online journals.Footnote 136 Nevertheless, commercial publishers have raised journal prices over the last 30 years, placing substantial pressure on library budgets.Footnote 137 Publishers claim these price hikes are justified by their need to invest in journal management and development and in expensive digital technology so they can build their databases and implement new publishing platforms.Footnote 138 They also seek to justify them on the grounds of the expertise they provide in improving academic content, which ensures the product quality of their journals: manuscripts submitted to a journal are assessed and selected by the journals’ editors, revised by peer reviewers, and proofread to ensure the manuscript includes all revisions and complies with style guides.

Yet, journal editors and peer reviewers are qualified members of the academic community, who are not usually paid for their services by the publishing companies.Footnote 139 Today, the typical academic journal receives all its content for free; writing, editing, reviewing, and all other processes related to knowledge production are conducted by academics and researchers, and indirectly paid for by their respective institutions.Footnote 140 Publishers’ contributions, which include proofing amendments, typesetting, language editing and publishing, can be done with very little material investment. For this reason, it has been suggested that academia might give some consideration to bringing more scholarly publishing functions in-house, instead of paying high fees to allow their researchers to read the work they themselves have done.Footnote 141

Obviously, neither journal subscriptions nor APCs or BPCs address solely the recouping of the cost of editorial input: they also serve to make profit. Indeed, various authors criticize the “black box” of academic publishing costs for charging excessively and for the disproportionate profit margins of around 40%.Footnote 142 All the signs are that large academic publishers are imposing abusive fees and bundling practices on research institutions, and that the sector should be subject to greater scrutiny under competition law. OA publishing could be an opportunity to adjust publishers’ income by setting fair APCs and BPCs that strike a better balance between their costs and profits.

5 Conclusion

The conventional model of scholarly publishing uses the copyright system as a lever to ensure that commercial publishers profit from disseminating the results of scholarly research. This is achieved by imposing copyright licenses on every copy, distribution, or further communication of their publications. OA publishing represents a significant change to this system, as publishers only charge a fee for their services, that is to say they make scholarly articles and books freely available from their journals and databases with virtually no copyright restrictions. If universal OA is achieved, journal subscriptions and book sales will cease, and publishers’ income will be based solely on a fee charged for each article and book published in OA.

The role of copyright in the development of OA scholarly publishing is limited, given that the main issue is how an OA system can be implemented financially; above all, it remains to be seen who will pay the commercial publishers, university presses and learned societies for OA publishing, and how fair publishing fees will be fixed.

Publishers have contributed to organizing and improving research publications, producing highly specialized journals over the last two centuries. They continue to play a vital role in scientific publishing. The path towards OA clearly has to be negotiated with these publishers, rather than restricting publishers’ rights or imposing compulsory licenses on them. Agreements between commercial publishers and institutions would constitute the most appropriate legal instrument in the search for a sustainable business model for OA, provided that those agreements include principles of party autonomy and contractual freedom to set fair publishing fees. In this new publishing market, competition law can play a key role in developing a model for sustainable universal OA.

Notes

Shaheed (2014), p. 17.

Suber (2012), p. 4.

Bammel (2014), p. 339.

The EU Research and Innovation Program Horizon (2021–2027) does not cover APCs in the case of subscription journals; Commission Staff Working Document, Impact Assessment Accompanying the document Proposals for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing Horizon Europe, Brussels, 7-6-2018, SWD (2018) 307 final, part 2/3, p. 106.

See the statement made by STM Publishers (Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers) on embargo-free OA in repositories: https://www.stm-assoc.org/rightsretentionstrategy/.

Suber (2012), p. 130.

Willinsky (2009), p. 47.

Guibault (2011), p. 160.

Shavell (2010), p. 302.

Suthersanen (2003), p. 602.

Moscon (2015), p. 116.

De la Cueva and Méndez (2022), p. 11.

Willinsky (2022), p. 3.

Geiger and Jütte (2023), p. 6.

Bellia and Moscon (2022), p. 61.

Chapman (2009), p. 1.

Helfer and Austin (2011), p. 234.

Art. 27 UDHR declares that “(1) Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits. (2) Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he [or she] is the author”.

Plomer (2013), p. 175.

Art. 15.1 ICESCR states that “[t]he States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone: (a) To take part in cultural life; (b) To enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications; (c) To benefit from the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he [or she] is the author”.

Chapman (2009), p. 6.

Chapman (2009), p. 6.

Yotova and Knoppers (2020), p. 668.

Article 15.2 ICESCR states that “[t]he steps to be taken by the States Parties to the present Covenant to achieve the full realization of this right shall include those necessary for the conservation, the development and the diffusion of science and culture”.

Yotova and Knoppers (2020), p. 682.

Yotova and Knoppers (2020), p. 671.

CJEU judgment of 6 October 2020 Commission v. Hungary (Higher Education), C-66/18, EU:C:2020:792, para. 225.

Geiger and Jütte (2023), pp. 43–44.

Geiger and Jütte (2023), p. 44.

Senftleben (2022), p. 12.

Chapman (2009), p. 2.

See para. 12(a) of the Venice Statement “The Right to Enjoy the Benefits of Scientific Progress and its Applications”, UNESCO (Venice 2009).

Ibid para. 8.

Chapman (2009), p. 6.

Stichweh (2009), pp. 82–90.

“Draft Recommendation on Open Science”, adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO in November 2021, available at https://en.unesco.org/science-sustainable-future/open-science/recommendation

Ibid paras. 6 and 9.

Kohler (1907), p. 143.

See Bulletin de l’Association littéraire internationale (1883), No. 18, p. 5.

Gálvez-Behar (2011), p. 21.

Ricketson and Ginsburg (2006), p. 406.

The UK Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988 establishes in Art. 1 that “[c]opyright is a property right which subsists in accordance with this Part in the following descriptions of work – (a) original literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works”, the French Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle (Loi Nº 92-597 of July 1992) states in Art. L.111-1 that “[t]he author of a work of the mind shall enjoy in that work, by the sole fact of its creation, an exclusive intangible property right that is enforceable against all persons”, and Art L.112-2 considers “works of the mind within the meaning of this Code: 1. Books, pamphlets and other literary, artistic and scientific writings”. [emphasis added]

The German Copyright Act of 9 September 1965 states in Sec. 1 that “[t]he authors of works in the literary, scientific and artistic domain enjoy protection for their works in accordance with this Act” and the Spanish Copyright Act of 1996 declares in Art. 1 “[t]he intellectual property in a literary, artistic or scientific work shall belong to the author thereof by virtue of the sole act of its creation”. [emphasis added]

Loewenheim and Leistner (2020), p.69.

Bercovitz Rodriguez-Cano (2017), p. 159.

Quaedvlieg (2016), p. 654.

CJEU judgment of 1 December 2011 Painer v. Standard Verlags GmbH, C-145/10, EU:C:2011:798, paras. 88-89.

Kohler (1907), p. 143.

Galvez-Behar (2011), p. 90.

Salitskaya (2019), p. 464.

Bently and Biron (2014), p. 242.

Casas (2009), p. 102.

See Art. 7 of Directive 96/9/EC on the legal protection of databases.

Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society.

Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC.

See Art. 5(3).(a) ISD.

Strowel and Ducato (2021), p. 303.

Geiger and Jütte (2023), pp. 54–55.

See European Commission (2016), Commission Staff Working Document, Impact Assessment on the modernisation of EU copyright rules, Part I, Brussels, 14.9.2016 SWD (2016) 301 final, p. 104.

Senftleben (2022), p. 37.

See Art. 3 DSMD.

See Recital 10 DSMD.

Strowel and Ducato (2021), p. 301.

Griffiths et al. (2022), p. 13.

The Finch Report was drafted by a committee set up by the UK government to expand access to research publications, especially as regards publicly funded research. Available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Finch_Group_report.pdf.

United Kingdom research and innovation OA policy 2022, 3 https://www.ukri.org/publications/ukri-open-access-policy/.

Art. 37(2) of Ley 14/2011 de la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Innovación (Spanish Law 14/2011 on Science, Technology, and Innovation).

Recital 5 of Commission Recommendation (EU) 2018/790 of 25 April 2018 on access to and preservation of scientific information, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32018H0790

See SPARC Europe, “Opening Knowledge, Retaining Rights and Open Licensing in Europe in 2023”, p. 2. Available at https://sparceurope.org/opening-knowledge/.

Bellia and Moscon (2022), p. 72.

In the UK, a growing number of HEIs have adopted the Scholarly Communications Licence, which allows authors to grant the university a non-exclusive license to make their accepted manuscript available without delay through the university’s OA repositories under the terms of a Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC). Cf. Baldwin and Pinfield (2018) p. 3 for a more detailed discussion of UK HEIs.

Angelopoulos (2022), p. 33.

Bellia and Moscon (2022), pp. 64–67.

Baldwin and Pinfield (2018) p.7 refer to UK academics. In Germany, Roland Reuß, professor of literary studies at the University of Heidelberg, criticized the German government proposal to make OA mandatory for all publicly funded research, (see http://www.textkritik.de/digitalia/con_crema.htm), and Jeffrey Beall, in the US, considers that a social movement that needs mandates to work is doomed to fail, Beall (2013), p. 594.

Moscon (2015), p. 107.

See, e.g., Anderson, “cOAlition S’s Rights Confiscation Strategy Continues”, The Scholarly Kitchen, 20 July 2020, https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2020/07/20/coalition-ss-rights-confiscation-strategy-continues/.

Khoo (2021), p. 6.

Peifer and Ohly (2020), p. 835.

Wandtke (2010), p. 185.

Rodríguez Tapia (1992), p. 294.

Cavanillas (2017), p. 930.

Owen (2013), p. 247.

Caddick et al. (2021), p. 488.

According to Art. 1:201(1) Principles of European Contract Law (PECL), “[e]ach party must act in accordance with good faith and fair dealing”; according to Art. 1:301(4) PECL “‘non-performance’ denotes any failure to perform an obligation under the contract, whether or not excused, and includes delayed performance, defective performance, and failure to co-operate in order to give full effect to the contract”. [emphasis added]

McKendrick (2021), p. 392.

Art 9: 502 PECL states that “[t]he general measure of damages is such sum as will put the aggrieved party as nearly as possible into the position in which it would have been if the contract had been duly performed. Such damages cover the loss which the aggrieved party has suffered and the gain of which it has been deprived”.

Cf. SPARC Europe, “Opening Knowledge: Retaining Rights and Open Licensing in Europe in 2023” (Note 71) p. 17.

Cf. SPARC Europe, “Opening Knowledge: Retaining Rights and Open Licensing in Europe in 2023” (Note 71), p. 80.

De Castro (2020), p. 4.

See Sec. 38(4) German Copyright Act (Bundesgesetzblatt 2013 Teil I, p. 3346).

See Art. 25fa Dutch Copyright Act (Staatsblad 2015, p. 258), Art. 37(a) Austrian Federal Law on Copyright in Literary and Artistic Works and Related Rights (Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I, No. 99/2015).

Art. 30 of Loi, n. 2016-1321 du 7 octobre 2016 pour une République numérique [Law No. 2016-1321 of 7 October 2016 for a Digital France] (JORF, Journal officiel «Lois et Décrets», No. 0235 of 8 October 2016).

Art. 29 of the Law on Miscellaneous Economic Provisions of 30 July 2018] (Belgisch Staatsblad No. 209, p. 68691)

Angelopoulos (2022), pp. 33–35.

Hansen (2005), pp. 378–388, p. 379.

Quaedvlieg (2016), p. 655.

Senftleben (2014), p. 10.

Visser (2015), p. 878.

Maddi et al. (2021), p. 3137.

On the difficulties of adopting SPR as an EU copyright exception, cf. Angelopolus (2022), pp. 37–53.

May (2020), p. 126.

Cf. SPARC Europe, “Opening Knowledge: Retaining Rights and Open Licensing in Europe in 2023”, (Note 71), p. 80.

Bell (2014), p. 144.

Schimmer et al. (2015), p. 5.

Szprot et al. (2021), p. 10.

See https://esac-initiative.org/about/transformative-agreements/. The ESAC initiative was established in 2014 to promote workflow efficiencies and library-driven standards in the management of OA article processing charges.

See the registry of TAs at https://esac-initiative.org/about/transformative-agreements/agreement-registry/.

The Spanish National Research Council comprises some 100 research institutes in disciplines that include medicine, chemistry, physics, and biology. The R&P agreement with OUP can be consulted at https://esac-initiative.org/about/transformative-agreements/agreement-registry/oxf2020csic/. At present, the average APC per article is EUR 2,300. Cf. Borrego et al. (2021), p. 225.

Anders et al. (2021), p. 132.

Szprot et al. (2021), p. 51.

See clause 5.2.e of the Wiley “Read and Publish” framework agreement with the Spanish Conference of University Chancellors (CRUE) available at https://www.crue.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/MoU-WILEY.pdf.

See, for Elsevier’s copyright overview and authors rights on exclusive license for publishing in OA https://www.elsevier.com/about/policies-and-standards/copyright#0-overview.

English law is recognized as the governing law in the R&P agreement between the Spanish National Research Council and Oxford University Press (available at https://esac-initiative.org/about/transformative-agreements/agreement-registry/oxf2020csic/) and in the R&P agreement between the University of Barcelona and Cambridge Law Review. In contrast, the general collaboration agreement between Springer and CRUE covering R&P agreements between Springer and Spanish Universities recognizes Spanish law as the governing law, available at https://www.crue.org/proyecto/acuerdos-con-editoriales/.

Westkamp (2022), p. 1044.

Bently (2021), p. 30.

Asai (2021) p. 32.

Mueller-Langer and Scheufen (2013), p. 365.

Borrego et al. (2021), p. 219.

Larivière et al. (2015), p. 3.

The “big five” are Elsevier (2,928 journals), Springer (2,920 journals), Taylor & Francis (2,508 journals), Wiley (1,607 journals) and SAGE (1,151 journals). See https://wordsrated.com/academic-publishers-statistics/.

Eger and Scheufen (2018), p. 121.

Eger and Scheufen (2018), p. 17.

Puehringer et al. (2021), p. 2.

The EUA represents 800 universities across Europe and 33 National Rectors’ Conferences. The EUA’s statement entitled “The lack of transparency and competition in the academic publishing market in Europe and beyond” is available at https://eua.eu/news/188:scholarly-publishing-eua-asks-european-commission-to-investigate-lack-of-competition.html.

Budzinski et al. (2020), pp. 2185 and 2203.

Whish and Bailey (2015), p. 187.

CJEU judgment of 16 March 2000 Compagnie Maritime Belge Transports and Others v. Commission, Case C-395/96 ECLI:EU:2000:132, para. 38.

See EU Commission Draft of the “Communication from the Commission: Commission Notice on the definition of the relevant market for the purposes of Union competition law”, pp. 10–11, available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_6528.

Macculloch and Rodger (2021), p. 228.

Business Models and Market Structure within the Scholarly Communications Sector, International Science Council, p. 6. Available at https://council.science/publications/business-models/.

McMahon (2023), p. 139.

Flynn (2010), p.150.

CJEU judgment of 14 February 1978 United Brands Co v. Commission, Case C-27/76, ECLI:EU:C:1978:22, para. 251.

May (2020), p. 122.

Eger and Scheufen (2018), p. 17.

See, Business Models and Market Structure within the Scholarly Communications Sector, International Science Council, September 2020, pp. 10–16, available at https://council.science/publications/business-models/.

May (2020), p. 122.

Michael et al. (2016), p. 1404.

Litman (2006), p. 794.

References

Anders A, Chesler A, Webster K, Rotjan S, Balduff D (2021) Read and publish – what it takes to implement a seamless model. Ser Libr 80:1–4

Angelopoulos C (2022) Study on the EU copyright and related rights and access to and reuse of scientific publications, including OA. Exceptions and limitations, rights retention strategies and the secondary publication right. European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. https://doi.org/10.2777/891665

Asai S (2021) Author choice of journal type based on income level of country. J Sch Publ 53(1):24–34

Baldwin J, Pinfield S (2018) The UK Scholarly Communication Licence: attempting to cut through the gordian knot of the complexities of funder mandates, publisher embargoes and researcher caution in achieving OA. Publications 6(3)31:1–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6030031

Bammel J (2014) The impact of copyright on the enjoyment of right to science and culture. Pub Res Q 30:335–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-014-9382-3

Beall J (2013) The open access movement is not really about open access. TripleC 11(2):589–597

Bell J (2014) OA: the journal is not dead. Leg Inf Manag 14:143–145

Bellia M, Moscon V (2022) Academic authors, copyright, and dissemination of knowledge: a comparative overview. In: Bonadio E, Sappa C (eds) The subjects of literary and artistic copyright. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 58–78

Bently L, Biron L (2014) Discontinuities between legal conceptions of authorship and legal practices. In: Van Eechoud M (ed) The work of authorship. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, pp 237–276

Bently L (2021) The past, present and future of the Cambridge Law Journal. Cambridge Law Journal 80, September pp 8–32

Bercovitz Rodríguez-Cano R (2017) Comentarios al art. 10. In: Bercovitz Rodríguez-Cano R (ed) Comentarios a la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual, 4th edn. Tecnos, Madrid, pp 159–193

Borrego A, Anglada L, Abadal E (2021) Transformative agreements: do they pave the way to OA? Learned Publishing 34(2):216–232

Budzinski O, Grebel T, Wolling J, Zhang X (2020) Drivers of article processing charges in open access. Scientometrics 14:2185–2206

Caddick N, Harbottle G, Suthersanen U (2021) Copinger and Skone James on copyright. Sweet and Maxell, United Kingdom, 18th edn

Casas R (2009) The requirement of originality. In: Derclaye E (ed) Research handbook on the future of EU copyright. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 102–133

Cavanillas S (2017) Comentarios al art. 48. In: Bercovit Rodríguez-Cano R (ed) Comentarios a la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual, 4th edn. Tecnos, Madrid, pp 918–939

Chapman AR (2009) Towards an understanding of the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its application. Journal of Human Rights 8:1–36

De Castro P (2020) Acuerdos transformativos con los editores: un controvertido paso adelante en la implantación del acceso abierto. Anuario ThinkEPI 14(1):1–9

De la Cueva J, Méndez E (2022) Open science and intellectual property rights. How can they better interact? State of the art and reflections. Report of Study. European Commission. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. https://doi.org/10.2777/347305

Eger T, Scheufen M (2018) The economics of open access. On the future of academic publishing (New Horizons in Law and Economics series), Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Flynn SM (2010), Using competition law to promote access to knowledge. Washington College of Law Research Paper No. 2010-24

Gálvez-Behar G (2011) The propertisation of science: suggestions for an historical investigation. Zeitschrift für Globalgeschichte und vergleichende Gesellschaftsforschung 21(2):89–97

Geiger C, Jütte B (2023) Conceptualizing a ‘right to research’ and its implications for copyright law: an international and European perspective. American University International Law Review 38:1–60

Griffiths J, Synodinou T, Xalabarder R (2022) Comment of the European Copyright Society addressing selected aspects of the implementation of articles 3 to 7 of Directive (EU) 2019/790 on Copyright in the Digital Single Market. European Copyright Society opinion. https://europeancopyrightsociety.org/2022

Guibault L (2011) Owning the right to open up access to scientific publications. In: Guibault L, Angelopoulos C (eds) Open content licensing: from theory to practice. Amsterdam University Press, pp 137–169. https://doi.org/10.5117/9789089643070

Hansen G (2005) Zugang zu wissentschaftlicher Information – alternative urheberrechtliche Ansätze. GRUR Int: pp. 378–388

Helfer L, Austin G (2011) Human rights and intellectual property: mapping the global interface. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kohler J (1907) Urheberrecht an Schriftwerken und Verlagsrecht. Verlag von Ferdinand Enke, Stuttgart

Khoo SY (2021) The Plan S Rights Retention Strategy is an administrative and legal burden, not a sustainable OA solution. Insights 34:1–6

Larivière V, Haustein S, Mongeon P (2015) The oligopoly of academic publishers in the digital era. PLoS ONE 10(6):1–15

Litman J (2006) The economics of open access law publishing. Lewis & Clark Law Review 10(4):779–795

Loewenheim U, Leistner M (2020) § 2 Geschütze Werke. In: Schricker G, Loewenheim U (eds) Urheberrecht Kommentar, 6th edn Beck, Munich

Maddi A, Lardreau E, Sapinho D (2021) OA in Europe: a national and regional comparison. Scientometrics 126(5):3131–3152

May C (2020) Academic publishing and OA: costs, benefits, and options for publishing research. Politics 40(I):120–135

MacCulloch A, Rodger BJ (2021) Competition law and policy in the EU and UK, 6th edn. Routledge, Abingdon

McKendrick E (2021) Contract law, 14th edn. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, London

McMahon K (2023) A re-evaluation of the abuse of excessive pricing. In: Akman P (ed) Research handbook on abuse of dominance and monopolization. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Moscon V (2015) Academic freedom, copyright, and access to scholarly works: a comparative perspective. In: Caso R, Giovanella F (eds) Balancing copyright law in the digital age. Springer, Berlin-Heidelberg, pp 99–135

Mueller-Langer F, Scheufen M (2013) Academic publishing and OA. In: Handke C, Towse R (eds) Handbook of the digital creative economy. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 365–378

Owen L (2013) Clark’s publishing agreements: a book of precedents. 9th edn Bloomsbury Professional, West Sussex

Peifer K-N, Ohly A (2020) §33 Weiterwirkung von Nutzungrechten. In: Schricker G, Loewenheim U (eds) Urheberrecht Kommentar. Beck, 6th edn Munich

Peters MA et al (2016) Towards a philosophy of academic publishing. Educ Philos Theory 48(14):1401–1425

Plomer A (2013) The human rights paradox: intellectual property rights and rights of access to science. Hum Rights Q 35:143–175. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2013.0015

Puehringer S, Rath J, Griesebner T (2021) The political economy of academic publishing: on the commodification of a public good. PLoS ONE 16(6):1–21

Quaedvlieg A (2016) The nature of the scholar’s right to publish in open access. In: Karnell G, Nordell P J, Kur A, Westman D, Axhamn DJ, Carlsson S (eds) Liber Amicorum, Jan Rosén, Eddy.se ab, Visby

Ricketson S, Ginsburg J (2006) International copyright and neighbouring rights, the Berne Convention and beyond, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford