Abstract

With the evolution of generative AI systems, machine-made productions in the literary and artistic field have reached a level of refinement that allows them to replace human creations. The increasing sophistication of AI systems will inevitably disrupt the market for human literary and artistic works. Generative AI systems provide literary and artistic output much faster and cheaper. It is therefore foreseeable that human authors will be exposed to substitution effects. They may lose income as they are replaced by machines in sectors ranging from journalism and writing to music and visual arts. Considering this trend, the question arises whether it is advisable to take measures to compensate human authors for the reduction in their market share and income. Copyright law could serve as a tool to introduce an AI levy system and ensure the payment of equitable remuneration. In combination with mandatory collective rights management, the new revenue stream could be used to finance social and cultural funds that improve the working and living conditions of flesh-and-blood authors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Generative AI systemsFootnote 1 are only capable of mimicking human creativity because human works have served as training material.Footnote 2 Machine-learning algorithms use existing literary and artistic creations as input data to recognize patterns and similarities. Following this deductive method, a generative AI system learns how to produce novel literary and artistic output by imitating the style of human works.Footnote 3 The machine-learning algorithm enables the generative AI system to generate literary and artistic content on its own – based on a computational analysis of the human works used as training material.Footnote 4

This insight makes it possible to lay theoretical groundwork for the introduction of a mechanism for remunerating human authors. Whenever copyright law measures are proposed to ensure that human authors receive an income, it is normally possible to argue that such income is intended to serve as an incentive and reward for creating literary and artistic works.Footnote 5 However, the potential of AI systems to imitate and replace human expression changes the equation. The moment AI systems become capable of flooding the market with literary and artistic productions, the question arises whether any additional incentive or reward for human creativity is still necessary. Why should society provide incentives for human literary and artistic creations when machines make similar literary and artistic products available in unlimited quantity and at lower cost? And why should society offer a reward for human literary and artistic labour when generative AI systems provide output that reflects only unprotected ideas, concepts and styles,Footnote 6 and no longer displays traces of free, creative choices made by a human author?Footnote 7 In this scenario, the act of creation is no longer carried out by a human author. Therefore, neither the incentive rationale nor the reward rationale is very persuasive.

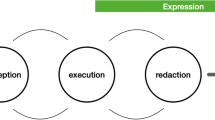

However, this need not be the final word. Other justifications – ranging from the parasitic use of human literary and artistic works and central functions of human art in society to broader socio-political objectives and arguments for improving AI – strongly support the introduction of a system for remunerating human authors (Sect. 2).Footnote 8 For the practical implementation of remuneration mechanisms, the legislator has two choices. On the one hand, remuneration could be made mandatory at the AI training stage. Arguably, human authors should be compensated for the use of their works in AI training, since a machine cannot produce results that resemble human literary and artistic works unless it has had the opportunity to analyse human creations (this is the input dimension, discussed in Sect. 3).Footnote 9 On the other hand, the focus could be on the offer of generative AI products and services in the marketplace (this is the output dimension). Instead of requiring the payment of remuneration at training level, a levy could be imposed on the final AI system capable of producing literary and artistic output. This AI levy could then be used to offer financial support, training opportunities and new literary and artistic projects for flesh-and-blood authors.Footnote 10 Providers of AI systems with the potential to serve as a substitute for human creations could be obliged to pay remuneration to collecting societies, which would then use the revenue to support human authors and their creative work.Footnote 11 At the same time, the levy could make the use of generative AI systems more expensive. By adding remuneration as an additional cost factor, a levy system could contribute to reducing the price advantage following from the fact that AI systems do not need to pay honoraria or salaries for creative labour (Sect. 4).Footnote 12 Weighing the arguments for and against these different implementation strategies, a legislative approach that focuses on the output/substitution dimension and seeks to introduce a lump-sum AI levy system is more promising than taking input and training activities as a reference point for remuneration (concluding Sect. 5).

2 Theoretical Groundwork

Generative AI systems are not true creators. They can imitate human literary and artistic expression only because they have been given the chance to analyse human creations. Against this background, it can be said – first – that human authors should be compensated for the parasitic usurpation of the market in literary and artistic production.Footnote 13 Machines are capable of mimicking human literary and artistic works only after having had the opportunity to derive the patterns for its own literary and artistic production from myriad human creations that served as resources for training purposes. Hence, it is only fair that human authors – who provide the source material for AI ingenuity – receive remuneration when AI productions finally kill the demand for the same human creativity that empowered the AI system to become a competitor in the first place.Footnote 14

Second, it has been demonstrated in the cultural sciences that human literary and artistic creations are of particular value to society as a whole.Footnote 15 Artwork by flesh-and-blood authors provides important impulses for social and political change by modelling experimental practices that open up new horizons for the development of society.Footnote 16 Human literary and artistic expression can mirror shortcomings in current society, unmask defects of existing social and political conditions, and prepare society for transitioning to a better model.Footnote 17 Arguably, AI-generated productions in the literary and artistic field are incapable of providing comparable impulses for the improvement of societal conditions. An AI system may manage to mimic human creativity and generate comparable literary and artistic output.Footnote 18 But it is not capable of penetrating the surface of a human artwork, going beyond its mere form of appearance, and assessing its message and meaning critically in the light of current societal conditions. AI systems do not perceive and experience social and political conditions as humans do. They are not affected by societal conditions in the same way as humans are.Footnote 19 Unable to experience and suffer contemporary societal conditions like a human, an AI system will inevitably fail to evoke visions of a new consensus on ethical norms that corresponds with people’s current desires.Footnote 20

Third, support for human authors is a positive and significant investment in new, innovative directions in the literary and artistic field: avant-garde movements that lead to new forms of expression and new reflections of societal conditions. AI systems cannot free themselves from the data input that fuels their algorithms. Therefore, they struggle to break rules, negate historical work templates and autonomously create anything that falls outside existing aesthetical categories – anything that brings chaos into the established order with a view to shedding light on tensions and conflicts in society and proposing change.Footnote 21 AI avant-garde experiments that strive for societal relevance are doomed to fail. AI output cannot transcend the horizon of expectation that has evolved from known societal conditions.Footnote 22 To preserve the central societal function of new, unexpected directions in the literary and artistic realm, it is thus advisable to ensure that human creativity survives the dethroning of the human author by generative AI systems. The introduction of a remuneration system that channels money to human art projects makes sense from this perspective. It prevents the loss of future avant-garde movements and the loss of important impulses for the improvement of social and political conditions that can follow from the critical impetus of new, surprising directions in the literary and artistic field. By leaving literary and artistic productions to AI systems, society would deprive itself of human impulses for future creativity and weaken its ability to evaluate and renew itself. The introduction of an AI remuneration system could halt this trend.Footnote 23

Fourth, there is a broader socio-political dimension. The replacement of human authors and the disruption of the market for literary and artistic productions will inevitably require adequate countermeasures and investment. Authors who lose their jobs will need financial support. Investment in training activities will be necessary to enable them to change course and obtain new skills and credentials. New production projects would allow authors to enter new fields of activity. In this situation, the introduction of a remuneration system that provides money for financial support, training activities and new literary and artistic projects is an important and desirable step. This broader socio-political rationale has a more universal field of application than the second argument given above. AI productions may win prizes and find their way into literary journals, concert halls, museums, and galleries,Footnote 24 but it seems unlikely (at least at this point in time) that they will entirely replace human creations in the fine arts segment. Creators of artwork with the potential described above to reflect societal conditions and provide impetus for social and political change may be less likely to be substituted than authors of everyday literary and artistic products and works of applied art. It is likely that the impact of AI will be felt much more strongly in areas such as news articles, comic book and video game production, illustration and decoration, background music for bars and restaurants, and so on.Footnote 25 In the latter segments, the mirror-of-society rationale may be less persuasive. However, as the risk of substitution becomes substantially higher, the general socio-political objective to mitigate replacement effects becomes more important. While general tax money could be used to help affected creatives adapt to the challenges of generative AI systems, the copyright framework offers crucial advantages by comparison. With collecting societies and their remuneration and repartitioning schemes, the copyright system offers a well-established infrastructure for the appropriate distribution of the monies collected.Footnote 26 Moreover, a copyright-based solution seems much more stable than a general tax measure that could be undone in the next financial crisis or when the tax system is reformed.

Fifth, it can be added that human literary and artistic work has societal value in and of itself. As Barton Beebe has argued on the basis of pragmatist aesthetics,Footnote 27 it is particularly important to the everyday individual to be able to participate in aesthetic practice and aesthetic play.Footnote 28 The active assimilation, appropriation, and creative recombination of aesthetic expression involved in the aesthetic play has intrinsic value. It constitutes a source of pleasure, of moral and political cultivation, of imaginative freedom and self-actualization.Footnote 29 To the extent to which aesthetic play is left to machines, humans in society lose opportunities to experience well-being, moral and political cultivation, imaginative freedom and self-actualization. When machines displace human authors from the literary and artistic field, they also deprive society of role models for human aesthetic engagement. While generative AI systems provide tools that allow human users to experiment with different styles and motifs for art production, the act of developing and entering a prompt in an AI system must not be confused with aesthetic play. The act of creation – the central element of aesthetic engagement – is then carried out not by the human user, but by the AI system. This has worrisome societal repercussions. Once literary and artistic production is primarily seen as the domain of machines, people might no longer have any reason to develop their own aesthetic practice or to play with different forms of expression themselves. The active assimilation, appropriation and creative recombination of literary and artistic works becomes the machines’ area of expertise. As a result, the potential of this practice to promote imaginative freedom and contribute to the cultivation and self-actualization of the individual in modern society is lost.Footnote 30 From this perspective, what matters is not that generative AI systems are capable of imitating human literary and artistic works. This is merely the end result of human creativity. What really matters is the creative process: aesthetic play. Giving instructions and pressing a button is not enough. What is crucial is the creative remixing and reusing of literary and artistic sources of inspiration.Footnote 31 AI systems that mimic human works degrade the remixing and reusing of literary and artistic source material to an automated process that can be left to machines. By establishing a remuneration system that provides human creators with the financial means to survive in the field of aesthetic engagement, society can give the important signal that aesthetic practice is and remains an important human activity with particular value. By retaining human authors in the literary and artistic field, this regulatory measure ensures that the role model of the human creator does not sink into oblivion, but can continue to inspire others to embark on aesthetic practice.

Sixth, the promotion of human literary and artistic production is good for the AI industry itself. It is an important and wise investment in the continuous improvement of generative AI systems. By financially supporting the continuous flow of new human creations, the AI industry can ensure that a rich spectrum of fresh human training material is constantly available for generative AI systems. A continuously enriched reservoir of human source material forms an important complement to past literary and artistic expression. By analysing historical human source materials, a generative AI system may be capable of endlessly recombining past expression. If the output of other AI systems is added to the training material, that AI system may also be able to further recombine what other machines have already recombined. Ultimately, however, the generative AI process remains in a permanent loop. If the source repertoire for AI training is not constantly refreshed and enriched, the AI output can hardly be expected to go beyond monochrome variations of known forms and styles. Thus, fresh human literary and artistic production is of particular value for the AI industry itself. To break out of the spiral of endless repetition of “the same old thing”, it makes sense to invest in human creativity. From this point of view, the payment of remuneration for the purpose of supporting and fostering human literary and artistic projects constitutes a legitimate policy goal that is in the AI industry’s own interest.

Hence, there are several good reasons for introducing mechanisms to ensure remuneration for the use of generative AI systems in the literary and artistic field. As already indicated above, this insight gives rise to the question of how best to implement such mechanisms in practice. On the one hand, the focus could be on the input dimension: the use of human literary and artistic creations for AI training purposes. On the other hand, the final output – the offer of generative AI products and services in the marketplace – could serve as a reference point for payments. To identify which implementation strategy is preferable, we need to explore both approaches more closely.

3 Input/Training Dimension

When remuneration mechanisms are aligned with the input dimension, particular importance is attached to the fact that human works are used to train the AI system. Interestingly, EU copyright law already provides a basis for linking remuneration to the AI training process: Article 4(1) of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (“CDSMD” or “CDSM Directive”)Footnote 32 contains a broad exception for text and data mining (“TDM”).Footnote 33 Under this TDM rule, anyone, including commercial AI system developers and trainers, may make copies of works or databases for the purposes of TDM and retain them as long as necessary for the AI training process.Footnote 34

By adopting a specific copyright exception in Art. 4 CDSMD, the EU legislature confirms that TDM and related AI training processes are relevant to copyright. This regulatory decision is not self-evident. In the TDM debate, it has been underlined around the globe that TDM copies are a special case. They fall outside the concept of reproduction in the traditional sense of making copies for the purpose of consulting and enjoying a work.Footnote 35 From a US perspective, Michael Carroll has pointed out that in the context of TDM:

copies are made only for computational research and the durable outputs of any text and data mining analysis would be factual data and would not contain enough of the original expression in the analysed articles to be copies that count.Footnote 36

Explaining the outright exemption of TDM activities in Art. 30-4(ii) of the Japanese Copyright Act, Tatsuhiro Ueno has pointed out that:

if an exploitation of a work is aimed at neither enjoying it nor causing another person to enjoy it (e.g. text-and-data mining, reverse engineering), there is no need to guarantee the opportunity of an author or copyright holder to receive compensation and thus copyright does not need to cover such exploitation. In other words, exploitation of this kind does not prejudice the copyright holder’s interests protected by a copyright law.Footnote 37

Criticizing the regulation of TDM in the EU, Rosanna Ducato and Alain Strowel described the following alternative approach:

when acts of reproduction are carried out for the purpose of search and TDM, the work, although it might be reproduced in part, is not used as a work: the work only serves as a tool or data for deriving other relevant information. The expressive features of the work are not used, and there is no public to enjoy the work, as the work is only an input in a process for searching a corpus and identifying occurrences and possible trends or patterns.Footnote 38

In fact, the distinction between use of “works as works” and use of “works as data” is not entirely new in the European copyright debate. In 2011, Mauricio Borghi and Stavroula Karapapa already developed the concept of “de-intellectualized use”Footnote 39 against the background of mass digitization projects, such as the Google Book Search. As Borghi and Karapapa point out, mass digitization turns protected content into mere data – with the result that “the expression of the idea embodied in the work is not primarily used to communicate the ‘speech’ of the author to the public but rather to form the basis of machine-workable algorithms.”Footnote 40

Considering these comments and observations, it becomes apparent that the EU legislator could have opted for a general exemption for TDM in the CDSM Directive.Footnote 41 Instead, Art. 4(1) CDSMD brings TDM under the umbrella of the right of reproduction and, therefore, within the reach of human authors seeking to receive remuneration for the use of their works in AI training processes.Footnote 42 Article 7(2) CDSMD confirms in this context that the three-step test known from Art. 5(5) of Information Society Directive 2001/29/EC (“ISD”)Footnote 43 is fully applicable. Accordingly, the TDM exception in Art. 4(1) CDSMD:

shall only be applied in certain special cases which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work or other subject-matter and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the rightholder.Footnote 44

3.1 Three-Step Test Arguments

The three-step test opens the way to arguments in favour of the payment of remuneration. Pointing to the risk of substitution, copyright holders could argue that the TDM rule allows the development of generative AI systems that erode the market for human creations. Attempts could then be made to demonstrate that allowing TDM to benefit from the exception in Art. 4(1) CDSMD conflicts with a normal exploitation.Footnote 45 Alternatively, right holders could argue that the TDM rule – allowing the use of human creations for the purpose of developing machines capable of killing demand for the very works used as training material – unreasonably prejudices the legitimate interest of human authors in earning income. Payment of remuneration could then be presented as a way out of the dilemma: as a tool to reduce the prejudice suffered to a permissible, reasonable level.Footnote 46

However, as Art. 4 CDSMD currently stands, these potential arguments about the three-step test remain mere theoretical options. They are doomed to fail because Art. 4(3) CDSMD expressly offers right holders the opportunity to reserve their rights, in particular by employing machine-readable means. The proviso that right holders can exclude TDM in this way means that, in order to assess whether TDM is permitted for a particular work or database, AI trainers must take into account metadata, such as robots.txt files, and terms and conditions of websites and online services.Footnote 47

In principle, right holders can thus rely on technical safeguards to prevent human creations from being used for AI training purposes. The impact of this rights reservation option on the three-step test analysis must not be underestimated. Opt-out rules, such as the rights reservation mechanism offered by Art. 4(3) CDSMD, can serve to avoid conflicts with a normal exploitation.Footnote 48 The underlying idea is simple: the right holder can render a copyright exception inapplicable by reserving its rights. This, in turn, would prevent beneficiaries of the copyright exception, such as AI trainers in the case of Art. 4 CDSMD, from eroding the normal exploitation of a work. In international law, the press privilege laid down in Art. 10bis(1) of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (“BC”) is based on the same opt-out solution:

It shall be a matter for legislation in the countries of the Union to permit the reproduction by the press, the broadcasting or the communication to the public by wire of articles published in newspapers or periodicals on current economic, political or religious topics, and of broadcast works of the same character, in cases in which the reproduction, broadcasting or such communication thereof is not expressly reserved.

The reservation of rights reflected in this provision entered the Berne Convention following debate on the protection of publications in newspapers and periodicals, and the freedom to use news information and newspaper articles with the exception of serial stories and tales.Footnote 49 From the perspective of the three-step test, the option to reserve rights may be deemed necessary to avoid a conflict with normal exploitation. The forms of exploitation covered by Art. 10bis(1) BC – reproduction, broadcasting and communication to the public – are central to the normal exploitation of press articles and broadcasts. Moreover, the exception relates to the initial exploitation period. Art. 10bis(1) BC explicitly refers to “current economic, political or religious topics.” Hence, it exempts the use of articles that are still fresh and have news value. However, as the right holder can opt out by reserving its rights, the risk of a conflict with a normal exploitation is minimized.

Considering Art. 10bis(1) BC, it can be said that opt-out rules, such as that enshrined in Art. 4(3) CDSMD, offer an instrument to experiment with relatively broad copyright exceptions. To ensure compliance with the three-step test, the potential adverse effect on the normal exploitation of a work can be minimized by giving right holders the opportunity to opt out. The use of this option in practice, then, will show whether right holders really see the copyright exception as a risk factor. The reservation of rights in Art. 10bis(1) BC, for instance, evolved from industry practice more than a century ago. At the time, newspapers saw the reproduction of their articles in other newspapers as a means of advertising and promoting their activities.Footnote 50 In particular, local newspapers with limited financial resources could hardly have satisfied their readers’ demand for news without reproducing articles from larger newspapers.Footnote 51

Applying these insights to the regulation of TDM in the EU brings the specific role of the rights reservation option in Art. 4(3) CDSMD clearly to the fore: it prevents a finding of lack of compliance with the three-step test. Allegations of conflict with a normal exploitation or of unreasonable prejudice to legitimate right holder interests can easily be rebutted. As Art. 4(3) CDSMD contains an opt-out possibility, right holders who fear usurpation of the market for human creations can prevent the AI system from using their works as training resources. As a result, the risk of causing a conflict with a normal exploitation or undermining legitimate right holder interests vanishes.

3.2 Rights Reservation Approach

While it seems safe to assume that the rights reservation option was added to Art. 4 CDSMD to strengthen the position of copyright owners vis-à-vis the high-tech industries,Footnote 52 the preclusion of conflict with a normal exploitation and of unreasonable prejudice appears as an unintended corollary from the perspective of authors and right holders with an interest in a lump-sum remuneration system. As the possibility of reserving copyright ensures compliance with the normal exploitation test and the unreasonable prejudice test, the three-step test – and the three-step test arguments outlined above – can no longer be used to support a plea for remuneration.

Hence the question arises whether the reservation of rights itself can lead to the payment of remuneration. In theory, this does seem possible.Footnote 53 It is conceivable that the creative industry and the AI high-tech industry reach agreement on machine-readable rights reservation protocols that express different right holder standpoints. A right holder seeking to express its preference for an outright prohibition of TDM could use a robots.txt file that categorically excludes any use of the literary and artistic work at issue for AI training purposes. A right holder wishing to express its willingness to permit use against the payment of remuneration could use a robots.txt file indicating green light for TDM on the condition that the AI trainer behind the crawler pay the requested lump-sum amount. In other words, in an ideal world, the rights reservation option in Art. 4(3) CDSMD could serve as a catalyst for generally agreed, machine-readable remuneration protocols, including protocols that trigger an automated process for the payment of remuneration.

3.3 Legal and Practical Obstacles

Unfortunately, it may be quite difficult to achieve this ideal result in the real world. First, the rights clearance infrastructure in the EU is highly fragmented.Footnote 54 Even if standardized rights reservation protocols – capable of expressing remuneration wishes and modalities – become available, it is unclear whether copyright holders and collecting societies will ever manage to create efficient, pan-European rights clearance solutions that offer reliable and well-functioning payment interfaces with the technical safeguards – robots.txt files, for example – that express the electronic remuneration caveat. As long as the automated, machine-based identification of right holders and the automated processing of payments remains complicated or unreliable, the rights reservation option in Art. 4(3) CDSMD is unlikely to pave the way for a successful remuneration system in practice. TDM requires vast amounts of literary and artistic works. The moment AI trainers are obliged to check rights ownership, observe specific payment conditions and obtain permission for individual works or databases, the burden of rights clearance will inevitably put an end to the whole remuneration endeavour.Footnote 55

Second, the need described above for standardized, machine-readable remuneration protocols under Art. 4(3) CDSMD indicates that, if satisfactory rights clearance solutions become available at all, they will most probably be the result of industry collaboration: the creative industry agreeing with the high-tech industry on conditional rights reservation protocols that allow use of protected material as soon as the desired remuneration has been paid. As with all types of industry collaboration, this approach raises the question whether the new revenue stream accruing from AI training will ever reach individual creators. If collecting societies are underrepresented at the negotiating table, additional income from TDM may merely fill the pockets of large companies that own impressive repertoires of literary and artistic works.Footnote 56 Individual creators whose works form part of these repertoires, however, will not necessarily receive higher honoraria or an appropriate share of the TDM income.

Third, it is foreseeable that, with or without generally agreed rights reservation protocols, there will still be trust issues. Who can guarantee that AI trainers will observe rights reservations made in accordance with Art. 4(3) CDSMD? And who can convincingly prove that a given work has been part of the AI training dataset when the final AI-generated output reflects only general style elements and bears no direct resemblance to a specific pre-existing work? In the context of the proposed AI Act,Footnote 57 the compromise text tabled by the European Parliament explicitly provides for additional transparency measures to open the “black box” of AI training in the field of literary and artistic works.Footnote 58 The Parliament proposes adding a new Art. 28b(4) dealing specifically with generative AI systems that are intended to produce complex text, image, audio or video output.Footnote 59 According to Art. 28b(4)(c), providers of such systems shall:

without prejudice to national or Union legislation on copyright, document and make publicly available a sufficiently detailed summary of the use of training data protected under copyright law.Footnote 60

The proposal for specific transparency rules in the area of generative AI systems need not be understood as an indication that remuneration models based on the rights reservation option in Art. 4(3) CDSMD must, by definition, fail. Nonetheless, the proposal sheds light on transparency and trust issues. Even if machine-readable remuneration protocols evolve from industry negotiations, it will remain difficult to control compliance with remuneration requirements and to ensure that remuneration payments are accurate in the sense of capturing all works used for AI training purposes.Footnote 61

Fourth, it must not be overlooked that the EU’s main international competitors have chosen TDM approaches that markedly depart from the EU’s focus on licensing. The US, Canada, Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Israel, and Taiwan have opted for broader, more flexible, copyright limitations.Footnote 62 Arguably, this regulatory approach gives high-tech companies in these countries more potential to innovate than their EU counterparts. In the US, TDM has routinely been considered to be transformative fair use, which is permissible without the prior authorization of the right holder, and does not generate claims for remuneration.Footnote 63 Japan implemented a broad TDM exemption in its copyright legislation in 2009.Footnote 64 The US and Japan are interesting examples because, while belonging to different copyright traditions, they both have thriving creative and cultural industries as well as a highly competitive high-tech sector in the field of AI.Footnote 65

Considering this global scenario, it is clear that impractical, complicated remuneration systems may put EU-based high-tech industries at a disadvantage compared with their peers in other legal systems. The need to obtain individual authorizations and manage remuneration payments for AI training constitutes an additional cost factor in the form of transaction costs and licensing fees. If the costs involved are too high, it will negatively impact the ability of the EU’s AI sector to compete on the world market.Footnote 66

In other words: a remuneration system based on the rights reservation option in Art. 4(3) CDSMD could easily lead to an unfortunate “lose-lose” scenario: no remuneration for authors and no access to copyrighted resources for AI trainers in the EU.Footnote 67 By virtue of Art. 4(3) CDSMD, copyright holders may manage to reserve their rights and prevent their works being used for AI training purposes on EU territory. However, successful rights reservation might not necessarily lead to licensing agreements and remuneration payments. Instead, the high-tech industry might decide to move AI training activities to other regions that offer a more favourable AI training environment. As a result, the bid for remuneration would fail: the EU right holder would not receive remuneration, and the AI trainer would look for training opportunities elsewhere.

4 Output/Substitution Dimension

Fortunately, the rights reservation mechanism in Art. 4(3) CDSMD is not the only avenue that could lead to new remuneration rules in favour of human authors. The European Parliament’s initiative to introduce specific transparency rules for generative AI systems clearly shows that new legislative projects, such as the proposed AI Act, can supplement and enrich existing copyright rules on the use of AI in the literary and artistic field. It is conceivable that new legislation will lead to the implementation of rules on remuneration specifically designed to create a new revenue stream for human authors in view of the disruptive effect and income losses caused by generative AI systems. As already indicated above, a remuneration mechanism need not focus on the AI training phase. The literary and artistic output of generative AI systems may also serve as a reference point for a legal obligation to pay remuneration. More specifically, it may be possible to create an AI system “levy”.Footnote 68

4.1 Towards an AI Levy System

Following this alternative approach, providers of generative AI systems would be obliged to pay remuneration for producing literary and artistic content that has the potential to replace human creations. The wording of the existing legal obligation to pay remuneration for the use of phonograms could serve as a blueprint. Using Art. 8(2) of the Rental, Lending and Related Rights DirectiveFootnote 69 as a model, the new rule could be formulated as follows:

Member States shall provide a right in order to ensure that a single equitable remuneration is paid by the provider of a generative AI system if literary and artistic output generated by the system has the potential to serve as a substitute for a work made by a human author, and to ensure that this remuneration is paid to social and cultural funds of collective management organizationsFootnote 70 for the purpose of fostering and supporting human literary and artistic work.Footnote 71

While the wording might need to be further refined and clarified before being adopted as a legal basis for the introduction of an AI levy system that supports human creativity, potential hurdles regarding definitions do seem surmountable. The Parliament’s draft text for the proposed AI Act, for instance, already defines “generative AI” in Art. 28b(4) as “foundation models used in AI systems specifically intended to generate, with varying levels of autonomy, content such as complex text, images, audio, or video”.Footnote 72 On the question of what output quality is required for there to be a risk of substitution, it must be borne in mind that the levy system is intended to serve as a lump-sum remuneration regime. Therefore, a general, abstract assessment of whether an AI system is capable of serving as a substitute for human literary and artistic productions may be deemed sufficient to confirm a disruptive effect and require payment of a levy.

The substitution test could also serve as a vehicle to draw a line between the use of AI to replace human creativity and its use to support human creativity. Introducing this distinction when configuring and applying the substitution test, lawmakers and judges could clarify that no levy payment would be required when human artists themselves used AI systems as mere tools to shape their own literary and artistic expression. In the traditional levy system for private copying, a similar distinction has been drawn between use of copying equipment, devices and media for private purposes (requiring levy payments) and use for professional purposes outside the private sphere (not requiring levy payments).Footnote 73

The general conceptual contours of the lump-sum-levy approach can be described as follows: the system would serve the overarching purpose of creating a new revenue stream to support the work of human authors. Revenue accruing from remuneration payments for the use of generative AI systems would be channelled to collecting societies, which would use the money for improving the living and working conditions of flesh-and-blood authors. In addition, making the payment of equitable remuneration mandatory would make the use of AI-generated content more expensive. AI system providers could no longer offer generative AI tools for free – unless they were willing to pay the remuneration out of their own pockets. Hence, introducing a levy system would also reduce the attractiveness, in terms of cost, of automated AI content production. Theoretically, AI remuneration could even be set at a level that would counterbalance lower production costs and enhance human authors’ chances of competing with generative AI systems. On its merits, the proposed system thus seeks to transform AI content revenue into human content revenue.Footnote 74

More concrete guidelines for the use of collected levies can be derived from the six objectives described above. Following the argument that the levy system offers compensation for the parasitic use of human works that enables AI systems to kill the market for human creativity (first argument), the levy could be used broadly to support human literary and artistic production. For instance, it is conceivable that monies collected could be distributed in accordance with a general repartitioning scheme aligned with the use of certain work repertoires or work genres for AI training purposes. Insights into prompts entered by users could provide additional reference points for calibrating the repartitioning scheme. Data showing that certain work categories, genres, etc. figure prominently in user prompts could provide a basis for increasing the revenue share for human authors operating in those areas. Support for a general repartitioning scheme could also follow from the objective to stimulate human aesthetic engagement and ensure that human role models remain visible in society to inspire everyday human literary and artistic practice (fifth argument). Considering the overarching goal of avoiding the impression that remixing and reusing literature and art are tasks for machines, it would seem appropriate for the levies collected to be distributed broadly across work categories and genres. The adoption of a general repartitioning scheme could also make sense from the perspective of the AI industry’s own interest in the continuous evolution of fresh human creations that could ultimately become training material for the further improvement and diversification of AI output (sixth argument).

By contrast, the insight that AI-generated content might lead to a loss of human works and avant-garde movements that, as a mirror of social and political conditions, can provide new directions for future creativity and impulses for improving society (second and third argument) might give rise to a more targeted approach. To the extent to which AI output is capable of replacing the human creativity that serves this societal function, the establishment of cultural funds that seek to promote human production in the high arts sector would seem warranted. Finally, the general socio-political goal of supporting human authors who lose their jobs because of competing AI content (fourth argument) would justify setting up social funds as insurance against displacement effects caused by generative AI systems. The six rationales developed above thus offer a basis for different measures – ranging from a general repartitioning scheme to more specific, targeted investment in social and cultural funds.

4.2 Foundation in Copyright Law

In terms of law and doctrine, the question arises whether copyright law offers an adequate basis for claiming remuneration in respect of AI output. Content produced by a generative AI system need not display protected traces of individual human expression.Footnote 75 The situation is unlike that of the AI training (input) perspective. During the AI training phase, protected human works are used in their entirety as learning resources for the AI system. Hence there is a direct link between the machine-learning process and the use of protected human literary and artistic works. Qualifying copies made for AI training purposes as relevant reproductions in the sense of copyright law, the legislator can create a legal basis for claiming remuneration.Footnote 76

In the case of AI output, the copyright basis for levy payments is less clear. Instead of reproducing individual expression – protected free creative choices by a human authorFootnote 77 – AI output may merely reflect unprotected ideas, concepts and styles.Footnote 78 However, the absence of protected human expression in AI output does not pose an insuperable obstacle. In fact, a copyright concept that could, by analogy, be invoked as a legal-doctrinal basis for the introduction of a levy system focusing on AI output was already developed in the last century.

In the discussion on the so-called domaine public payant, Adolf Dietz explained in a 1990 landmark article that, in addition to the traditional exploitation and remuneration rights of individual authors, it made sense and was advisable to recognize in copyright law a new right to which a different right holder – the “community of authors”Footnote 79 – was entitled as a collective. Dietz pointed out that this step could be regarded as a corollary of a modern understanding of copyright law “as part of a more comprehensive concept of culture law”.Footnote 80 Taking this broader role and responsibility of copyright as a starting point, the law is no longer condemned to accept “harmful discrepancies”Footnote 81 between the substantial profits made by those exploiting public domain works on the one hand, and the precarious working and living conditions of current authors on the other.Footnote 82 Instead, copyright can be employed as a legal tool to introduce a remuneration right as a means of redress for the community of living and creating authors:

What we finally propose is simply to introduce another right owner, namely the community of living and creating authors, among several kinds of right owners already existing in copyright law. This community of authors should have the direct right to participate in the income from exploitation of works of dead authors after the individual term of copyright protection has expired.Footnote 83

As this statement indicates, Dietz developed his concept of a new right for the community of authors with a focus on the exploitation of works in the public domain. He placed his proposal in the context of the discussion on the domaine public payant that had gained momentum after the Second World War.Footnote 84 From his perspective, soaring prices and income from the exploitation of public domain works in the field of literature, music, and art should, “at least partly and proportionally, also serve the living and creating generation of authors”.Footnote 85 Evidently, the introduction of a new – collective – right to participate in revenue accruing from the exploitation of public domain works begs the question how this new right of the community of living and creating authors might be exercised in practice. Dietz solves this problem by relying on the well-established system of collective rights management in Europe:

[T]here must be a natural or legal person or body ready to interfere and, in particular, to control the market and claim the participation right, if necessary in a lawsuit. In addition, this body must be able to distribute the incoming money according to statutory purposes and rules, preferably under government supervision … We should not forget, however, that these kind of bodies already exist, and have done so for decades, in the form of collecting societies.Footnote 86

Before turning to parallels between that remuneration concept and the AI levy system discussed here, it is noteworthy that, in the second half of the last century, the proposal for a domaine public payant did not remain just theoretical. In Germany, it formed part of the official government proposal for new copyright legislation that was discussed in 1965.Footnote 87 Although, in the end, the German legislator refrained from introducing a new remuneration right for the community of authors in the 1965 Copyright Act,Footnote 88 the fact that the domaine public payant was included in the government proposal shows that the concept and the underlying objective to improve the working and living conditions of authors had broad support in Germany.Footnote 89 An international UNESCO/WIPO survey conducted in 1982 also brought to light several approaches for implementing the domaine public payant in copyright law.Footnote 90 In more recent debates on recalibrating copyright, Rebecca Giblin confirmed the concept’s continued relevance and importance. In a critical assessment of the term of copyright protection, she qualified the domaine public payant as a useful reference point for her proposal to draw a clearer distinction between incentive and reward goals and introduce an opt-in “creator-right” that would give authors access to remuneration systems in return for the registration of their works after an initial term of protection.Footnote 91

The parallels between the domaine public payant and the proposed AI levy system are striking. Both concepts concern creations that fall outside the scope of the exploitation rights of individual authors: literary and artistic works that never enjoyed or no longer enjoy copyright protection in the case of the domaine public payant; and general ideas, concepts, and styles in the case of AI output that does not reproduce any individual expression of a human author. At the same time, it is clear that both concepts concern literary and artistic subject matter: public domain works, and public domain ideas, concepts, and styles. For AI output, it can even be added that pre-existing human creations have been a conditio sine qua non for the literary and artistic production at issue. Without human training material, the machine could not have generated the content. The same cannot be said about public domain masterpieces from the past. Current authors can hardly assert that these masterpieces depended on their creative input. In another respect, the argument in favour of remunerating the community of authors also seems stronger in the case of AI output than in the case of public domain works from the past. As Dietz’s line of reasoning shows very clearly, the proposal for a domaine public payant was based on the socio-political argument that something ought to be done in copyright law to overcome “the existential and financial misery of an artist’s life”.Footnote 92 While this argument certainly plays an important role in the AI levy debate as well (see fourth argument above), it is only one of six arguments that, as explained, can be advanced to underpin the introduction of an AI levy system. Hence there is even more reason to follow in Dietz’s footsteps and establish a system of mandatory levies for generative AI systems. As a new right holder in copyright law, the community of authorsFootnote 93 should be entitled to benefit from AI levies under this new system. Moreover, the collective remuneration right should be administered and enforced by collecting societies – ideally, by one central pan-European collecting societyFootnote 94 – which would distribute the monies collected through repartitioning schemes and social and cultural funds.

The precursor of the domaine public payant thus shows that potential legal-doctrinal concerns need not thwart the introduction of an AI levy system focusing on AI output. Even if AI output merely reflects unprotected ideas, concepts and styles, it is still possible and still makes sense to incorporate a lump-sum remuneration right into copyright law as a collective right of the community of authors: a new right subject to mandatory collective rights management.

4.3 Legal and Practical Advantages

Finally, it must not be overlooked that an output-based AI levy system offers several important practical advantages over the above-mentioned input-based remuneration architecture that could be built on the rights reservation option in Art. 4(3) CDSMD.

First, an output-oriented AI levy system could be applied uniformly to all providers of generative AI systems in the EU. In contrast to a remuneration obligation focusing on the input dimension and AI training activities, an output-oriented levy approach does not entail disadvantages for EU high-tech industries. All providers of generative AI systems are equally required to pay levies when offering their products or services in the EU. A levy based on the final offer of generative AI products and services might even reduce the imbalances described above between the EU and other countries and regions at the level of AI training. With the rights reservation option in Art. 4(3) CDSMD, the EU has adopted an AI training rule that is more burdensome than TDM rules in many other countries, including the US and Japan.Footnote 95 However, an output-oriented AI levy system as described could reduce barriers to content access and obstacles to rights clearance that might arise from the reservation of rights under Art. 4(3) CDSMD.Footnote 96 To achieve this goal, it could be clarified in the context of AI levy legislation that individual authors and right holders could only benefit from levies, related repartitioning schemes and social and cultural funds if they refrained from invoking Art. 4(3) CDSMD to reserve their rights. Benefits accruing from AI levies would thus be used as bait to convince authors and right holders not to exercise the rights reservation option and instead offer unrestricted access to their work repertoire. The introduction of an output-oriented AI levy system could thus transform the “lose-lose” scenario described above into a “win-win” situation: authors would receive remuneration, and AI trainers would obtain broader access to copyrighted material in the EU.

Second, an AI levy raises fewer trust and transparency issues. In contrast to input-oriented remuneration approaches focusing on AI training activities, an output-oriented levy system would not depend on information on the use of specific works as training resources – information that high-tech companies might class as protected secret information.Footnote 97 As already pointed out, the levy system would require the payment of a global lump sum, for instance consisting of a certain percentage of the revenue that AI companies derive from advertising, subscription fees, or other payments from users. In the case of profit-oriented providers of generative AI systems, the levy might also consist of a certain percentage of annual turnover. The possibility of aligning the levy with the number of AI-generated literary and artistic products or the number of prompts entered by users could also be explored.

Third, mandatory collective rights management in the area of AI levies ensures that, in line with collecting societies’ statutory purposes and rules for social and cultural funds,Footnote 98 individual creators can benefit directly from the extra income accruing from levy payments. In contrast with industry collaboration under Art. 4(3) CDSMD, the proposed levy approach does not give rise to concerns that the monies collected are unlikely to reach individual creators. The repartitioning schemes of collecting societies explicitly provide for direct payments to authors.Footnote 99

Fourth, a lump-sum levy would not require the management of use permissions at the level of individual works. As explained above, the reservation of copyright on the basis of Art. 4(3) CDSMD will only lead to the payment of remuneration if a machine-readable rights reservation is transformed into a permission for TDM against payment. However, this would require a well-functioning rights clearance infrastructure capable of interacting with the content crawlers used for AI training purposes. An output-oriented AI levy, by contrast, would not pose any comparable practical obstacles. It would not concern the AI training phase. Nor, as a collective right of the community of authors, would it require any inquiries into individual rights ownership, use permissions, and payment modalities.

5 Conclusion

Generative AI systems are likely to replace human creations and usurp the market for human literary and artistic works. As they can provide literary and artistic output much faster and cheaper than human authors can, the latter might find themselves facing shrinking market share and loss of income. This development has a broader societal dimension. Arguments for appropriate regulatory measures include compensation for the parasitic use of human works, the socio-political objective of offering financial support to human authors who lose their jobs, the need to preserve the important societal functions of human artwork, the desire to promote human aesthetic practice and encourage avant-garde movements leading to new, innovative directions in the literary and artistic field, and the AI industry’s own interest in the continuous evolution of fresh human productions. To enable human authors to continue their socially valuable work and invest time and effort in literary and artistic creations, it is advisable to introduce remuneration rules that offer financial support for human creativity.

The rights reservation option following from Art. 4(3) CDSMD could serve as a basis for a remuneration system focused on the use of human creations for AI training purposes. However, given the legal and practical difficulties involved in this approach, it seems preferable to follow an alternative path and introduce an output-oriented levy system that imposes a general payment obligation on all providers of generative AI systems in the EU. In contrast to remuneration systems based on AI training activities, this alternative approach would not weaken the position of the European AI sector or make the EU less attractive as a region for AI development. Even more importantly, an output-oriented AI levy system can be combined with mandatory collective rights management. Collected levies can be distributed to authors and right holders in accordance with repartitioning schemes established for that purpose. The levies may also be used to finance social and cultural funds to improve the working and living conditions of human authors who find themselves replaced. With an output-oriented levy approach, it is thus possible to ensure that the new revenue stream reaches individual creators directly.

Notes

For an attempt at a legal definition of generative AI, see European Parliament (2023), Art. 28b(4). For examples of current generative AI products and services, see Stability.ai’s Stable Diffusion, available at: https://stability.ai/stablediffusion; Midjourney, available at: https://www.midjourney.com/home/; OpenAI’s DALL-E, available at: https://openai.com/dall-e-2; Adobe Firefly, available at: https://www.adobe.com/sensei/generative-ai/firefly.html.

In this category, a distinction can be drawn between “machine-learning” and “deep-learning” algorithms. See Gervais (2020), pp. 2055–2059; Ginsburg and Budiardjo (2019), pp. 401–402; Deltorn (2018), pp. 173–174; Bridy (2012), p. 3; Boden (2009), p. 23. For a practical example of AI-generated imitations of human vocals, see https://www.theguardian.com/music/2023/apr/18/ai-song-featuring-fake-drake-and-weeknd-vocals-pulled-from-streaming-services.

Russell and Norvig (2010), pp. 693–717.

For a more detailed discussion of incentive and reward arguments in the context of AI-generated content, see Senftleben and Buijtelaar (2020), pp. 804–808.

Article 9(2) of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPS”); Art. 2 WIPO Copyright Treaty (“WCT”). As to the role of the idea/expression dichotomy in the generative AI debate, see Lemley and Casey (2021), pp. 772–776. With regard to the approach in the EU, see Dutch Supreme Court, 29 March 2013, ECLI:NL:HR:2013:BY8661, Broeren and Duijsens, para. 3.5; Senftleben (2020), pp. 27–28.

As to the traditional copyright originality test requiring free, creative choices by a human author, see CJEU, 16 July 2009, case C-5/08, Infopaq International, para. 45; CJEU, 1 December 2011, case C-145/10, Painer, para. 89. As to the impact of this originality test on copyright protection for AI productions in the literary and artistic field, see Hugenholtz and Quintais (2021), pp. 1212–1213; Burk (2020), pp. 270–321; Ginsburg and Budiardjo (2019), pp. 395–396; Janssens and Gotzen (2018), pp. 325–327; Pearlman (2018), p. 4.

For an earlier recommendation to rely on collecting societies to improve the living and working conditions of authors, see Dietz (1990), pp. 15–17.

As to the potential of generative AI systems to replace human creativity in different sectors, see Mok and Zinkula (2023), who explicitly list “Media jobs (advertising, content creation, technical writing, journalism)” and “Graphic designers” as risk categories. Frosio (2023a), p. 1, describes replacement risks in the area of comic book creation, poem and novel writing, news articles, musical compositions, photograph editing, video game creation, and the making of paintings and other artwork. See also Quintais and Diakopoulos (2023); Beckett (2019), pp. 24–25; Trendacosta and Doctorow (2023); Deltorn (2018), pp. 173–174; Yanisky and Moorhead (2017), p. 662; Bridy (2016), p. 397; Denicola (2016), p. 251; Ralston (2005), p. 283.

Cf. Senftleben (2020), pp. 54–64.

For a description of the functioning of “creative” AI systems, see Senftleben and Buijtelaar (2020), pp. 802–804.

On this contribution of artwork to the improvement of societal conditions, see Schiller (1794–1795), pp. 120–121 (Letter 27).

On this requirement for societal relevance of literary and artistic productions, see Osborne (2013), pp. 203–211.

Cf. Dietz (1990), pp. 15–16.

Beebe (2017), p. 347.

Beebe (2017), pp. 346–347.

As to the political dimension of this educational effect of art, see Beebe (2017), pp. 336–337, who describes the belief of “early-republic Americans” that the progress of the fine arts promises to promote the “overall progress of civic virtue and good government.”

Beebe (2017), pp. 390–391.

Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC, Official Journal of the European Communities 2019 L 130, 92.

Article 4(1) and (2) CDSMD. On the relevance of Art. 4 CDSMD to generative AI systems, see Quintais (2023).

Cf. Senftleben (2022c), pp. 1495–1502.

Carroll (2019), p. 954.

Ueno (2021), pp. 150–151.

Ducato and Strowel (2021), p. 334.

Borghi and Karapapa (2011), p. 45.

Borghi and Karapapa (2011), pp. 44–45.

Cf. Senftleben (2022c), p. 1502.

Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001, on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society, Official Journal of the European Communities 2001 L 167, 10.

Article 5(5) ISD.

How successful such an initiative would be is unclear. According to CJEU, 17 January 2012, case C-302/10, Infopaq International II, para. 51, the CJEU may, when inquiring into a potential conflict with a normal exploitation, confine itself to assessing the economic significance of the exempted act of TDM as such. It is unclear whether the CJEU would be willing to consider the broader economic impact, including all subsequent steps up to the final offer of generative AI products and services in the marketplace.

See Recital 18 CDSMD, which clarifies that “[i]n the case of content that has been made publicly available online, it should only be considered appropriate to reserve those rights by the use of machine-readable means, including metadata and terms and conditions of a website or a service”. Cf. Hugenholtz (2019), p. 170.

For a more detailed discussion, see Senftleben (2014), pp. 12–16.

Guibault (2002), p. 58, on the rationales underlying the newspaper exemption.

See Guibault (2012), pp. 444–445: “Hardly any newspaper in those days could survive without citing or borrowing articles from prestigious foreign publications.”

On this general objective of the CDSM Directive, see also Arts. 18–23 CDSMD.

Cf. Senftleben et al. (2022), p. 67, para. 7.

Cf. Trendacosta and Doctorow (2023), predicting “the perverse effect of limiting this technology development to the very largest companies, who can assemble a data set by compelling their workers to assign the ‘training right’ as a condition of employment or content creation”.

European Commission, 21 April 2021, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and Amending Certain Union Legislative Acts, Document COM(2021) 206 final.

European Parliament (2023), Art. 28b(4).

European Parliament (2023), Art. 28b(4)(c).

Cf. the critical remarks by Quintais (2023).

Senftleben et al. (2022), pp. 72–73, paras. 11–12.

The Japanese Copyright Act envisages an exception for TDM that is not limited to non-commercial or research only purposes, see Art. 47septies Japanese Copyright Act reported and discussed in Guibault and Margoni (2015), pp. 373–414 and 396. See also Caspers et al. (2016), pp. 75–76; Ueno (2021), pp. 145–152.

Senftleben et al. (2022), pp. 72–73, paras. 11–12.

Cf. Lemley and Casey (2021), pp. 770–771.

As to theoretical groundwork for this approach, see Geiger (2018), pp. 448–458.

Council Directive 92/100/EEC of 19 November 1992 on rental right and lending right and on certain rights related to copyright in the field of intellectual, Official Journal of the European Communities 1992 L 346, 61.

On the place for social and cultural funds of collecting societies in EU copyright law, see CJEU, 11 July 2013, case C-521/11, Amazon.com International Sales and Others, paras. 49–52. Cf. Senftleben (2017), pp. 64–68.

European Parliament (2023), Art. 28b(4).

Lemley and Casey (2021), pp. 772–776.

For a more detailed, legal-comparative discussion of this policy option, see Senftleben (2022c), pp. 1495–1502. As to its implementation in the EU, see Arts. 3 and 4 CDSMD, and the discussion above.

CJEU, 16 July 2009, case C-5/08, Infopaq International, para. 45; CJEU, 1 December 2011, case C-145/10, Painer, para. 89.

Article 9(2) TRIPS; Art. 2 WCT. Cf. Dutch Supreme Court, 29 March 2013, ECLI:NL:HR:2013:BY8661, Broeren and Duijsens, para. 3.5; Senftleben (2020), pp. 27–28

Dietz (1990), p. 15.

Dietz (1990), p. 13.

Dietz (1990), p. 13.

Dietz (1990), p. 13.

Dietz (1990), p. 14.

On the historical origin and development of the domaine public payant, see Dillenz (1983), pp. 920–922.

Dietz (1990), p. 14.

Dietz (1990), p. 15.

Dietz (1972), pp. 14–15.

Act on Copyright and Related Rights (Urheberrechtsgesetz), official English translation available at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_urhg/ (last visited on 11 July 2023).

Cf. Dietz (1972), pp. 14–15.

UNESCO/WIPO (1982).

Giblin (2017), pp. 200–203 and 207–208.

Dietz (1990), p. 13.

Dietz (1990), p. 15.

On the advantages of one single collecting society covering the entire EU territory, see Senftleben (2019), pp. 481–482.

Senftleben et al. (2022), pp. 72–73, paras. 11–12.

On the protection of trade secrets in the EU, see Art. 2(1) of Directive (EU) 2016/943 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2016 on the protection of undisclosed know-how and business information (trade secrets) against their unlawful acquisition, use and disclosure, Official Journal of the European Union 2016 L 157, 1. Cf. Art. 39(2) TRIPS.

Cf. CJEU, 11 July 2013, case C-521/11, Amazon.com International Sales and Others, paras. 49–52.

In the context of repartitioning schemes of collecting societies, the individual creator is in a relatively strong position. With regard to national case-law explicitly stating that a remuneration right improves individual creators’ income, see German Federal Court of Justice, 11 July 2002, case I ZR 255/00, Elektronischer Pressespiegel, 14–15. For a discussion of the individual creator’s entitlement to income from the payment of equitable remuneration, see Westkamp (2008), pp. 55–59; Quintais (2017), pp. 335–336, 340–341, 347–349 and 356–357; European Copyright Society (2015).

References

Adorno TW (1970) Ästhetische Theorie. In: Adorno G, Tiedemann R (eds) Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main

Beckett C (2019) New powers, new responsibilities—a global survey of journalism and artificial intelligence. London School of Economics, London

Beebe B (2017) Bleistein, the problem of aesthetic progress, and the making of American copyright law. Columbia Law Rev 117:319

Boden M (2009) Computer models of creativity. AI Mag 30:23

Borghi M, Karapapa S (2011) Non-display uses of copyright works: Google Books and beyond. Queen Mary J Intellect Prop 1:21

Bridy A (2012) Coding creativity: copyright and the artificially intelligent author. Stanf Technol Law Rev 5:1

Bridy A (2016) The evolution of authorship: work made by code. Columbia Law J Arts 39:395

Burk D (2020) Thirty-six views of copyright authorship, by Jackson Pollock. Houst Law Rev 58:263

Carroll MW (2019) Copyright and the progress of science: why text and data mining is lawful. U.C. Davis Law Rev 53:893

Caspers M, Guibault L et al (2016) Future TDM—baseline report of policies and barriers of TDM in Europe. Institute for Information Law, Amsterdam

Communia (2023) Using copyrighted works for teaching the machine. Communia Policy Paper 15, 26 April 2023. https://communia-association.org/policy-paper/policy-paper-15-on-using-copyrighted-works-for-teaching-the-machine/. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

Cramer F (2019) Crapularity-Ästhetik. Dystopien zeitgenössischer Kunst – und das unterschiedliche Erbe von kritischer Theorie und Konzeptualismus in der Bildenden Kunst und Neuen Musik. Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 180, No. 4:12

Deltorn J-M (2018) Disentangling deep learning and copyright. Tijdschrift voor auteurs-, media- en informatierecht 172

Denicola RC (2016) Ex machina: copyright protection for computer-generated works. Rutgers Univ Law Rev 69:251

Dewey J (1934) Art as experience. Perigee, New York 1934, pp 4–10

Dietz A (1972) Die sozialen Bestrebungen der Schriftsteller und Künstler und das Urheberrecht. Gewerblicher Rechtsschutz und Urheberrecht 11

Dietz A (1990) A modern concept for the right of the community of authors (Domaine public payant) Copyright Bulletin 24:13

Dillenz W (1983) Überlegungen zum Domaine Public Payant. Gewerblicher Rechtsschutz und Urheberrecht – International 920

Ducato R, Strowel A (2021) Ensuring text and data mining: remaining issues with the EU copyright exceptions and possible ways out. Eur Intellect Prop Rev 43:322

European Composer and Songwriter Alliance/European Writers’ Council et al (2023) Joint statement from authors’ and performers’ organisations on artificial intelligence and the AI Act—true culture needs originals: transparency and consent are key to the ethical use of AI. https://screendirectors.eu/joint-statement-from-authors-and-performers-organisations-on-artificial-intelligence-and-the-ai-act/. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

European Copyright Society (2015) Opinion on Reprobel. European Copyright Society 2015. https://europeancopyrightsociety.org/opinion-on-reprobel/. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

European Guild for Artificial Intelligence Regulation (2023) Manifesto for AI companies regulation in Europe. https://www.egair.eu/#manifesto. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

European Parliament (2023) Draft compromise amendments on the draft report—proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and Amending Certain Union Legislative Acts, Document KMB/DA/AS, Version 1.1, dated 16 May 2023

Frosio G (2023a) The artificial creatives: the rise of combinatorial creativity from Dall-E to GPT-3. In: Garcia-Murillo M, MacInnes I, Renda A (eds) Handbook of artificial intelligence at work: interconnections and policy implications. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham (forthcoming). https://ssrn.com/abstract=4350802. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

Frosio G (2023b) Should we ban generative AI, incentivise it or make it a medium for inclusive creativity? In: Bonadio E, Sganga C (eds) A research agenda for EU copyright law. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham (forthcoming). https://ssrn.com/abstract=4527461. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

Geiger C (2018) Freedom of artistic creativity and copyright law: a compatible combination? UC Irvine Law Rev 8:413

Geiger C (2021) The missing goal-scorers in the artificial intelligence team: of big data, the right to research and the failed text-and-data mining limitations in the CSDM Directive. In: Senftleben MRF, Poort J et al (eds) Intellectual property and sports—essays in honour of Bernt Hugenholtz. Kluwer Law International, The Hague, p 383

Geiger C (2024) When the robots (try to) take over: of artificial intelligence, authors, creativity and copyright protection. In: Thouvenin F, Peukert A et al (eds) Innovation—creation—markets, Festschrift Reto M. Hilty. Springer, Berlin (forthcoming)

Geiger C, Iaia V (2023) The forgotten creator: towards a statutory remuneration right for machine learning of generative AI. Comput Law Secur Rev (forthcoming). https://ssrn.com/abstract=4594873. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

Gervais D (2020) The machine as author. Iowa Law Rev 105:2053

Giblin R (2017) Reimaging copyright’s duration. In: Giblin R, Weatherall K (eds) What if we could reimagine copyright? ANU Press, Canberra, p 177

Ginsburg JC, Budiardjo LA (2019) Authors and machines. Berkeley Technol Law J 34:343

Guibault L (2002) Copyright limitations and contracts—an analysis of the contractual overridability of limitations on copyright. Kluwer Law International, The Hague

Guibault L (2012) The press exception in the Dutch Copyright Act. In: Hugenholtz PB, Quaedvlieg AA, Visser DJG (eds) A Century of Dutch copyright law—Auteurswet 1912–2012. deLex, Amstelveen, p 443

Guibault L, Margoni T (2015) Legal aspects of open access to publicly funded research. In: OECD (ed) Enquiries into intellectual property’s economic impact. Chapter: 7, OECD 2015. https://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/intellectual-property-economic-impact.htm. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

Handke C, Guibault L, Vallbé J-J (2015) Is Europe falling behind in data mining? Copyright’s impact on data mining in academic research. In: Schmidt B, Dobreva M (eds) New avenues for electronic publishing in the age of infinite collections and citizen science: scale, openness and trust—proceedings of the 19th international conference on electronic publishing. IOS Press, Amsterdam, p 120

Hargreaves I (2011) Digital opportunities—a review of intellectual property and growth. UK Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, London

Hilty RM, Richter H (2017) Position statement of the Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition on the proposed modernisation of European copyright rules—part B: exceptions and limitations—Art. 3 text and data mining. Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition Research Paper Series 2017-02, 1

Hugenholtz PB (2019) Artikelen 3 en 4 DSM-richtlijn: tekst- en datamining. Tijdschrift voor auteurs-, media- en informatierecht 167

Hugenholtz PB, Quintais JP (2021) Copyright and artificial creation: does EU copyright law protect AI-assisted output? Int Rev Intellect Prop Compet Law 52:1190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-021-01115-0

Initiative Urheberrecht (2023) Joint statement: authors and performers call for safeguards around generative AI in the European AI Act, 19 April 2023. https://urheber.info/diskurs/call-for-safeguards-around-generative-ai. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

Janssens M-C, Gotzen F (2018) Kunstmatige Kunst. Bedenkingen bij de toepassing van het auteursrecht op Artificiële Intelligentie. Auteurs en Media 2018-2019, 323

Keller P (2023) Protecting creatives or impeding progress? Machine learning and the EU copyright framework. Kluwer Copyright Blog, 20 February 2023. https://copyrightblog.kluweriplaw.com/2023/02/20/protecting-creatives-or-impeding-progress-machine-learning-and-the-eu-copyright-framework/. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

Lemley MA, Casey B (2021) Fair learning. Texas Law Rev 99:743

Mok A, Zinkula J (2023) ChatGPT may be coming for our jobs. Here are the 10 roles that AI is most likely to replace. Business Insider 4 June 2023

Osborne P (2013) Anywhere or not at all—philosophy of contemporary art. Verso, London

Pearlman R (2018) Recognizing artificial intelligence as authors and investors under U.S. intellectual property law. Richmond J Law Technol 24:1

Quintais JP (2017) Copyright in the age of online access—alternative compensation systems in EU law. Kluwer Law International, Alphen aan den Rijn

Quintais JP (2023) Generative AI, copyright and the AI Act. Kluwer Copyright Blog, 9 May 2023. https://copyrightblog.kluweriplaw.com/2023/05/09/generative-ai-copyright-and-the-ai-act/. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

Quintais JP, Diakopoulos N (2023) A primer and FAQ on copyright law and generative AI for news media. Generative AI Newsroom, 26 April 2023. https://generative-ai-newsroom.com/a-primer-and-faq-on-copyright-law-and-generative-ai-for-news-media-f1349f514883. Last visited on 15 Oct 2023

Ralston WT (2005) Copyright in computer-composed music: HAL meets Handel. J Copyr Soc USA 52:281

Ricketson S, Ginsburg JC (2022) International copyright and neighbouring rights—the Berne Convention and beyond, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Russell SJ, Norvig P (2010) Artificial intelligence: a modern approach. Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River

Sag M (2009) Copyright and copy-reliant technology. Northwest Univ Law Rev 103:1607

Sag M (2019) The new legal landscape for text mining and machine learning. J Copyright Soc USA 66:291

Samuelson P (2021) Text and data mining of in-copyright works: is it legal? Commun ACM 64:20

Schiller F (1794–1795) Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen. In: Berghahn KL (ed) Reclam, Stuttgart 2000

Senftleben MRF (2004) Copyright, limitations and the three-step test: an analysis of the three-step test in international and EC Copyright Law. Kluwer Law International, The Hague

Senftleben MRF (2014) How to overcome the normal exploitation obstacle: opt-out formalities, embargo periods, and the international three-step test. Berkeley Technol Law J Comment 1(1):1

Senftleben MRF (2017) Copyright, creators and society’s need for autonomous art—the blessing and curse of monetary incentives. In: Giblin R, Weatherall K (eds) What if we could reimagine copyright? ANU Press, Canberra, p 25

Senftleben MRF (2019) Bermuda Triangle: licensing, filtering and privileging user-generated content under the new Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market. Eur Intellect Prop Rev 41:480

Senftleben MRF (2020) The copyright/trademark interface—how the expansion of trademark protection is stifling cultural creativity. Kluwer Law International, The Hague

Senftleben MRF (2022a) Works of authorship and the single equitable remuneration for AI substitutes. In: Fischer V, Nolte G, Senftleben MRF, Specht-Riemenschneider L (eds) Gestaltung der Informationsrechtsordnung – Festschrift für Thomas Dreier zum 65. C.H. Beck, Geburtstag, München, p 111

Senftleben MRF (2022b) A tax on machines for the purpose of giving a bounty to the dethroned human author—towards an AI levy for the substitution of human literary and artistic works. IViR Working Paper. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4123309. Last visited on 25 Sept 2023

Senftleben MRF (2022c) Compliance of national TDM rules with international copyright law—an overrated nonissue? Int Rev Intellect Prop Compet Law 53:1477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-022-01266-8