Abstract

The climate crisis has added circularity and sustainability arguments to those of competition and the consumer-friendly justification of limitations to design and trade mark rights. The increasingly widespread “right to repair” has changed consumer knowledge and understanding. This article presents the results of experimental studies on the perception of trade marks used in the commercialisation of spare parts and the impact thereof on how a product’s origin and quality are perceived. Against this background, there is a discussion of the recent referral by a Polish court, in case C-334/22, Audi, concerning the problem of spare parts that reproduce a trade mark as an element of the appearance of the part.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Whether we like it or not, the “right to repair” (R2R) is slowly becoming a reality from which we cannot and should not escape. Whilst, so far, competition considerations have not sufficiently convinced all the EU Member States to introduce a repair clause into their design law, the impending climate catastrophe is changing the situation radically. The power of particular economic interests wanes in the light of the valid societal interests that follow from environmental policy, which include extending the lifespan of products to reduce waste and preserve natural resources. The ability to repair products and the availability of spare parts are becoming a market standard to which all market participants, including consumers, are growing accustomed. Consequently, the “right to repair” has the potential to significantly impact market communications, of which trade marks are an essential tool. Has R2R already changed marketing customs and consumers’ perceptions? Should the decisions of courts be informed by the rapidly changing market reality in this case?

Using a trade mark in the context of repairs raises numerous concerns, especially when the trade mark concerned is that of the manufacturer of the original product, and the replacement part originates from an independent manufacturer. Trade marks can be used to commercialise spare parts and communicate the purpose of a spare part; they can also appear on reused, refurbished,Footnote 1 recycled and upcycled goods.Footnote 2 Each scenario requires separate consideration in the context of trade mark protection metrics. Another particular case is the use of trade marks as a component of the appearance of a spare part. Such parts fulfil their role properly only when the mark is fully reproduced. The absence of a trade mark right limitation (relating specifically to the reproduction of a mark as an element of a spare part offered for repair purposes) encourages re-examination of existing trade mark protection mechanisms.Footnote 3 A deeper insight into consumer perception may affect the existing, relatively backward, line of interpretation for both trade mark right infringement and limitations criteria.

So far, this problem has been somewhat overlooked and treated as a special issue in the car spare parts market, but it goes beyond the automotive industry.Footnote 4 As the linear economy becomes increasingly circular, there will be more and more situations in which the role and limits of trade mark protection will be questioned. So far, trade mark law has been interpreted with the help of sound and efficient pro-competition arguments but not with any arguments relating to sustainability or circularity. The environmental crisis that is imposing this Copernican turn in the economy and prompt abandonment of the linear consumption model (based on the “take, make, waste” paradigm) will bring different values and societal interests into trade mark infringement disputes too. There is no doubt that trade mark law will be unable to remain immune to these challenges.

This article aims to present some of those challenges in the context of spare parts commercialisation and to discuss possible legal responses. First, the emerging R2R in the EU will be discussed in Sect. 2, followed by its specific manifestation in EU design law in the form of the repair clause presented in Sect. 3. Section 4 explores the problems arising in the EU trade mark regime when assessing the use of trade marks on spare parts legally manufactured under the repair clause provided in design law. Next, Sect. 5 discusses the role of consumer understanding in adjudicating trade mark infringement. Section 6 presents the results of empirical studies on consumer perception of trade marks in the context of commercialising spare parts for cars. Finally, Sect. 7 elaborates on the recent Polish referral to the CJEU in case C-334/22, Audi, which concerns the problems discussed. This is followed by a brief conclusion in Sect. 8.

2 R2R in the EU

In 2020, the European Commission adopted a new Circular Economy Action Plan for a cleaner and more competitive Europe (CEAP)Footnote 5 as one of the main building blocks of the European Green Deal,Footnote 6 which is the new agenda for Europe on sustainable growth. It aims to make the EU economy fit for a green future, strengthen its competitiveness whilst protecting the environment, and give new rights to consumers. It links environmental issues to competitive ones. The CEAP has announced, in particular, a sustainable product policy framework that aims to counter premature obsolescence and improve the sustainability and repairability of all products in the European market. It recommends revising EU consumer lawFootnote 7 to establish a new “right to repair” and new horizontal material rights for consumers, including consumer information on repairability and the lifespan of products, and the availability of repair services, spare parts and repair manuals (e.g. sustainability labels and the EU-wide repair score).Footnote 8

Thus, the right to repair has acquired, in Europe, a critical environmental underpinning, firmly rooted in primary EU law (Art. 11 TFEUFootnote 9 and Art. 37 of the EU CharterFootnote 10). It is evolving right before our eyes from a buzzword that started an R2R movement into a more concrete legal project derived primarily from ecodesign measures.Footnote 11 Indeed, environmental arguments enrich its purely economic rationale, which is related to freedom of consumer choice, competition-related issues, and access to economically attractive repairs.Footnote 12 Additionally, it is noted that consumers need access to reliable, trustworthy and relevant information on issues such as the repairability and durability of products to help them make environmentally sustainable choices. Several changes are expected in European consumer and unfair commercial practices law to enforce this.Footnote 13

This new set of European laws is likely, at least in the EU, to change thinking, attitudes and behaviour towards repairs, access to repair information, the availability of spare parts, planned obsolescence and, in the longer run, consumerism. The following three aspects of the universal R2R need to be addressed in Europe so that it is not just an empty slogan with illusory content: (1) good product design, (2) fair access to spare parts and repairs, (3) informed consumers. The first and third aspects seem to be addressed adequately by the CEAP. However, there is still insufficient awareness and debate about the need to respect the R2R within the intellectual property protection framework in order to provide fair access to spare parts and make repairs economically attractive. This means not only access to replacement parts in general but also access, at a reasonable price, to the open market of spare parts, including those from an independent source in competition with the original manufacturer.

The CEAP states that “[t]he regime for intellectual property needs to be fit for the digital age and the green transition and support EU businesses’ competitiveness”.Footnote 14 To ensure that intellectual property remains a key enabling factor for the circular economy, on 25 November 2020, the Commission proposed an Intellectual Property Strategy.Footnote 15 This raises the issue of how to ensure that unfair or excessively restrictive IP practices do not block repair and re-use.Footnote 16 The partial harmonisation of design protection for component parts used for the repair of complex products, which fragmented the economically critical spare parts market, is blamed for severely distorting competition and hampering the transition to a more sustainable and greener economy.Footnote 17 Apart from the restrictions on the independent manufacture and sale of spare parts because of their possible protection under copyright, design or trade mark law, the problem of software and TPMs as legal obstacles to repair and reuse is also acute in Europe.

3 R2R and Spare Parts in EU Design and Trade Mark Law

The design regime is perhaps the first one in which the problem of repairs and access to spare parts has been so explicitly addressed as it is in the tailor-made limitation referred to as the “repair clause”. The scope of design protection for spare parts has been a hot topic in EU intellectual property law for years. The search for a compromise solution is marked, first, by the economic policy of the European Union, which aims at market liberalisation and undistorted competition and, second, by the economic interests of individual Member States. The “repair clause”, introduced into the unitary EU design regime in 2002 in Art. 110(1) CDR,Footnote 18 limits the Community design right in cases that concern the component parts of a complex product used for repairing that product so as to restore its original appearance. The need to ensure competition in the aftermarket for spare parts is at the heart of this. However, in the process of harmonising national design law, no common position regarding the repair clause could be found.Footnote 19 The situation, which for years seemed immovable, is now undergoing dynamic change.Footnote 20

At present, European design law reformers understand that there is no way back to the status quo ante and that the repair clause should also be a mandatory limitation for national design rights.Footnote 21 It is expected that a repair clause in the revised Design Directive will impose a mandatory limitation on design rights in all EU Member States. As the CJEU underlined in Acacia,

the purpose of the repair clause is to avoid the creation of captive markets in certain spare parts and, in particular, to prevent a consumer who has bought a long-lasting and perhaps expensive product from being indefinitely tied, for the purchase of external parts, to the manufacturer of the complex product.Footnote 22

As a result, from this perspective, the point is not just access to spare parts in general, as the original manufacturer can offer those,Footnote 23 but also access to cost-effective alternatives from independent sources. In fact, in the case of older models of complex products, the price determines access to wear-and-tear replacement parts and repairs.

The requirements of the circular economy make both forms of access to spare parts vital. The environmental crisis necessitates supplementing this pro-competition approach and consumer-friendly justification of the repair clause with circularity and sustainability arguments.Footnote 24 The Commission has understood this and put the reform of EU design law on the agenda for the transition to a green economy.Footnote 25 The environmental needs and the large-scale work required to implement R2R will inevitably force appropriate solutions not only in design law but also in copyright law, which has the potential to impede the full effect of the essence of the right to repair.Footnote 26

So far, however, the problem has not received sufficient attention in the EU trade mark regime, which does not provide a limitation parallel to the repair clause. At first glance, such limitation seems unnecessary, as trade mark protection serves a radically different purpose from typical exclusive intellectual property rights. Trade marks, by their very nature, should not block access to the market for products. However, the expansion of this protection, both in terms of subject matter and content, means that trade marks can indeed jeopardise full exercise of the right to repair. It is possible that the questions referred by the Polish Court to the CJEU this year in case C-334/22, AudiFootnote 27 will provoke deeper reflection on the problem of spare parts that reproduce a trade mark as an element of the appearance of those parts.

Until now, the CJEU has assumed, as in Ford,Footnote 28 that the repair clause provided for in the design regime could not be applied per analogiam in trade mark law because harmonised EU trade mark law has its own catalogue of limitations, which should not be exceeded by national courts. Consequently, the trade mark cannot be reproduced as an element of the appearance of the spare part without the consent of the right holder, even if the resulting use made of that trade mark is the only way of repairing the vehicle concerned and restoring a complex product to its original appearance.Footnote 29 In Acacia, however, the CJEU underlined that the purpose of repair (i.e. restoring the original appearance of a complex product) may be achieved only by parts that are visually identical to the original parts.Footnote 30 The absence of identity, which should be assessed considering all the factors that create the appearance of the product (i.e. features of the lines, contours, colours and shape,Footnote 31 among which a trade mark is not an immaterial detail), takes non-identical parts out of the scope of the repair clause. A change in the appearance of the spare part (e.g. by affixing a different trade mark or removing it entirely) may make it unsuitable to perform its function correctly. As a result, the ban on offering replacement parts with the trade mark as a necessary element of their appearance means that independent spare part manufacturers cannot offer users a full range of products.

Whilst the Acacia ruling does not explicitly propose a solution to this problem, it does include express conditions for reliance on the repair clause. A manufacturer or supplier of replacement parts that intends to rely on this limitation is obliged to ensure that downstream users comply strictly with the conditions of the clause. The duty of diligence, with regard to further stages of distribution, consists of a set of duties regarding information to be provided (i.e. clear and visible information on the product, on the packaging, in catalogues and commercial documents, to the effect that the product reproduces the protected design of another entity and is intended only for the purpose of repairing a complex product in order to restore its initial appearance).Footnote 32 It certainly establishes the standards of honest practice in the commercialisation of spare parts.

4 Problems Under EU Trade Mark Law

4.1 Is It Use as a Trade Mark?

The problem with spare parts that contain the trade mark of the original manufacturer of a complex product and are offered by independent spare part manufacturers can be approached in two ways under trade mark law. First, the legal basis for addressing this situation in EU trade mark law is provided in the conditions for trade mark right infringement outlined in Art. 9 EUTMR.Footnote 33 A trade mark that appears on spare parts manufactured and offered for sale is being used “in the course of trade”. As regards general infringement criteria, a first doubt arises, however, as to whether there is “use in relation to goods”Footnote 34 and “use that adversely affects the functions of the trade mark” in such cases.Footnote 35

Use of the trade mark of an original parts manufacturer as a necessary feature of the appearance of a spare part legally manufactured and offered within the limits of the repair clause need not be perceived as use for the purposes of distinguishing goods or services, i.e. as an indication of the commercial origin of such parts.Footnote 36 In this case, use of the mark on the goods is necessitated by the need to realise the purpose of the repair clause fully, i.e. to produce and offer parts that, being a faithful visual reproduction of the originals, are identical thereto.

The fact that the individual part is sold in packaging and/or with labels that clearly indicate its true commercial origin (e.g. the trade mark of its independent spare parts’ manufacturer) and preclude confusion among spare parts purchasers (within the framework of controlled distribution, i.e. sales directed to professional users who make use of the parts in line with the repair clause) may significantly affect how buyers perceive such parts (buyers here being professional recipients within the narrow scope of the repair clause, not end users). The context of use of the trade mark can neutralise its impact as an indication of the commercial origin of a product.Footnote 37 Although trade mark right infringement is bound to formalised rules and based on an abstract assessment, consumer perception of a spare part that reproduces a trade mark as an element of its appearance can considerably affect this assessment, regardless of the valid normative considerations informing the final evaluation.

In individual cases, particularly with regard to the origin function jeopardised by use that creates the impression that there is a material connectionFootnote 38 between the goods of a third party and the original manufacturer of the complex product, market perception of such use may be decisive. The question arises then as to whether operation of the repair clause in EU design law has changed this perception and whether spare parts with the trade mark as a necessary element that are commercialised under conditions that eliminate or reduce confusion are perceived to originate from the “original” manufacturer or with its permission.

4.2 The Double Identity Clause

If, despite these fundamental doubts, it is established that, in the specific case of a spare part with a trade mark as an element of its appearance, there is use as a trade mark, then the various relevant forms of trade mark right infringement need to be analysed. First, the situation can be considered to fall under the ambit of the “double identity” clause outlined in Art. 9(2)(a) EUTMR. The general requirements for applying the double identity clause in such cases are prima facie fulfilled: the signs are (indeed must be) identical, and the goods are identical too.

Since there is no specific trade mark right limitation that directly corresponds to this situation, trade mark infringement should be analysed in-depth, with a thorough examination of whether the functions of the trade mark have been jeopardised in the case in question.Footnote 39 The issue is whether the allegedly infringing conduct jeopardises or risks jeopardising, in particular, the trade mark’s essential function of guaranteeing originFootnote 40 or any other protected trade mark functions, such as those related to quality, advertising, investment or communication.Footnote 41 So far, the CJEU has taken for granted that the origin function, understood as guaranteeing that all goods bearing the trade mark have been produced under the control of a single undertaking, which is accountable for their quality, is jeopardised in typical double identity cases. However, the question needs to be reformulated to ask whether use of the trade mark in this case affects the origin function to a sufficient degree to trigger application of the double identity clause.Footnote 42 This is then a normative issue.

It is opportune, when looking at the theory of functions as an instrument for determining the limits of protection of the proprietary interests of the trade mark holder, to introduce sustainability and environmental arguments. If spare parts purchasers are accustomed to the fact that such parts (which reproduce the trade mark as an immanent element of the original part manufacturer’s parts, which is not perceived as constituting an indication of the origin of the goods) are manufactured by different entities, then any threat to the origin function seems unlikely.Footnote 43 In the case of parts distributed within the limits of a repair clause, the relevant public is a specific and very restricted group of downstream users of the repair clause (i.e. professional circles, retailers and workshops to whom the spare parts were delivered) whose perception cannot be aligned with that of the end users of the complex products in which the parts are assembled.Footnote 44 This may result in differences in levels of attention between both groups, with higher levels potentially limiting or eliminating the risk of confusion.Footnote 45 In addition, the duty to provide information imposed by both the repair clause and the general conditions of the right to repair can significantly reduce confusion.Footnote 46

As regards the origin function, any confusion arising (which may be effectively eliminated if a trade mark is used strictly within the limits of a repair clause) should not be equated with the possible confusion triggered by third parties after purchase, i.e. when a spare part is fitted to the vehicle.Footnote 47 There are no grounds for extending the essential function of trade marks to guarantee to purchasers of complex products on the aftermarket that all their components come from the original manufacturer. The quality function of such trade marks is exhausted in the primary market. Buyers of used cars understand that a car is no longer brand new and that some of its components may have been damaged or worn out and need to be replaced. The role of product safety regulations and technical approvals is mainly to guarantee the quality and safety of spare parts installed in a complex product. The prevalence of the practice of repairing, refurbishing and reusing means that consumer expectations are also dynamically changing. The information provided to consumers in the secondary market strongly influences their quality expectations.

The use of a trade mark as a necessary element of a spare part forces complete control of the impact on the functions of the trade mark. This is the consequence of the lack of an appropriate trade mark right limitation that would allow scope for weighing opposing interests. The criterion of adverse impact on the functions of a trade mark should not be considered only as a determinant of the broad concept of trade mark infringement adopted by the CJEU,Footnote 48 but should also serve as an additional balancing instrument in infringement cases,Footnote 49 as expressed by Advocate General J. Kokott in her Opinion of 7.4.2011 in Viking Gas. She emphasised that “not every adverse impact on the functions of a mark should count as an infringement”.Footnote 50 Consequently, in specific circumstances, the negative impact of use on trade mark functions can be assessed as insignificant and not actionable.

In the case of spare parts, the interests of consumers and competitors, in particular the protection of free competition as the organising principle of the market in the EU, may prevail over the interests of the trade mark holder as embodied in the protected functions. Thus, if a spare part containing a trade mark as an element necessary for fully realising the purpose of the repair is sufficiently clearly labelled as not originating from the trade mark holder, and there are no links between the manufacturer of the parts and the trade mark holder, then, for the sake of the opposing valid interests and freedoms, infringement can be ruled out in an individual case. As aptly put by Annette Kur, the theory of the functions “presents a taxonomical scheme encapsulating the full spectrum of tasks that trade marks are meant to perform in the context of competitive markets” and “the protection of the additional functions is limited in its scope by the principle that third-party actions remain possible where they comply with sound competition”.Footnote 51 The linking of competition issues with the transition of the economy to a circular one broadens the range of interests that come into play in such cases. Conduct that not only conforms with the principles of competition but also with sustainability may, then, be considered legitimate.

The cases of spare parts that reproduce a trade mark as a mandatory element of their appearance may also provoke a review of the concept of a counterfeit mark.Footnote 52 The double identity clause was designed to combat counterfeits that infringe the trade mark holder’s interests even when the relevant public recognises that they are fake. In the context of the right to repair and requirements relating to circularity, the regulation of intellectual property piracy will need to be revisited. In the case of spare parts, features indicative of piracy are, at the same time, attributes required by the spare parts market. This need is particularly urgent in those jurisdictions where trade mark counterfeiting is subject to criminal liability, which can impede exercise of the right to repair.

4.3 Infringement of a Trade Mark with a Reputation

Under Art. 9(2)(c) EUTMR, the use of a trade mark as an element of a spare part offered by an independent manufacturer may also be considered an infringement of a mark that has a reputation if the mark used can be described as such and its use gives the user an unfair advantage or is detrimental to the reputation or distinctiveness of the mark. Unfair advantage focuses on the infringer’s gaining benefit (unjust enrichment),Footnote 53 for example in the form of higher prices negotiated for parts with marks than for “no-name” parts.Footnote 54 However, when there is no risk that the public will be led to believe that there is a commercial connection between the spare parts’ seller and the trade mark proprietor, the mere fact that the reseller gains an advantage (in the form of an aura of quality) from using the trade mark in practices that are otherwise honest and pro-competition is not sufficient to establish an unfair advantage.Footnote 55

The corrosive effects, such as detriment to the distinctive character or the repute of the mark, concern damage. Those effects, known as “blurring” and “tarnishment”, are assessed on the basis of the impact on the average consumer of the goods and services for which that mark is registered, who is reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect.Footnote 56 They require evidence of a change in the economic behaviour of the average consumerFootnote 57 or detriment to the power of attraction of the trade mark.Footnote 58 However, the loss of customers who will not buy an original spare part marketed with the permission of the trade mark owner, which is usually more expensive than a part offered by an independent spare parts manufacturer, should not constitute such evidence, as it is a natural effect of the existence of the repair clause.Footnote 59 Opening up competition in the spare parts market should not be taken as an indication of a negative impact on the investment function of a trade mark.Footnote 60 An assessment of whether the quality function is jeopardised should consider whether the quality level is impaired to the extent that it would seriously damage the reputation of the trade mark.

The criteria for the extended protection of trade marks with a reputation are flexible and do not always lend themselves to restrictive evaluation based on the evidence provided. They are balanced by a condition that legalises certain activities, i.e. the presence of a legitimate reason (due cause) for using the mark.Footnote 61 Indeed, this enables competing interests to be balanced against those of the holder of a reputed mark. A repair clause, as outlined in the Acacia judgment, is a vital due cause factor deriving from the freedom of competition and the freedom to conduct a business.Footnote 62 This, in addition, constitutes an objectively overriding reason, which, in many cases, justifies the use of a trade mark as a necessary element of a spare part in a way that enables full benefit to be derived from this limitation. Moreover, the absence of conflict with any protected trade mark function (see 4.2 above) may be a relevant factor for determining whether the use of a trade mark, as a necessary element of the appearance of a spare part, was made with due cause.Footnote 63

Taking into account the competing interests – those articulated and acknowledged in the Acacia judgment, in addition to those arising from the transition to a circular economy – as part of the assessments that determine whether trade mark use adversely affects the functions of the trade mark, whether there was a risk of confusion, whether an unfair advantage was taken without due cause and whether there is a legitimate reason for the use, may be the equivalent of the missing trade mark right limitation that would allow full use to be made of the repair clause in justified cases.

4.4 Trade Mark Right Limitations

Owing to the absence in EU trade mark law of a specific limitation parallel to the repair clause, the use of another person’s trade mark, which constitutes an intrinsic element of the appearance of a spare part, may be considered, under Art. 14(1)(b) EUTMR, as so-called "descriptive use".Footnote 64 In the context of use necessary for the commercialisation of spare parts offered under the repair clause, freedom of conducting business and freedom of competition may justify the need to use someone else’s trade marks for informative purposes.Footnote 65 The recently modified wording of Art. 14(1)(b) EUTMR, according to which the owner of a trade mark is not entitled to

prohibit a third party from using, in the course of trade, signs or indications which are not distinctive or which concern the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, the time of production of the goods or of rendering of the service, or other characteristics of the goods or services

may encourage considering this limitation as a useful option. The use of indistinctive signs has been declared permissible in the same way as the use of descriptive elements.

The question is whether the essence of this limitation after the reform lies in legitimisation of the use of signs or their elements having certain characteristics (being as such descriptive and non-distinctive), or rather in the purpose or context of the use, which in specific circumstances makes signs non-distinctive or descriptive (then the context of use and external circumstances are more important than the characteristics of the signs used). Prior to the reform, this distinction was blurred and use for descriptive purposes was covered by this defence. Footnote 66 It is not clear what the trade mark law reform has changed in this regard, considering also the significant extension of the referential use defence in Art. 14(1)(c) EUTMR. The question arises as to whether, in the light of this limitation, a trade mark that is owned by the “original manufacturer” and forms an indispensable element of a spare part constitutes a characteristic of the goods within the meaning of Art. 14(1)(b) EUTMR, and whether it can be used by a manufacturer of non-original spare parts to faithfully reflect the characteristics of the product following its intended use.Footnote 67 It seems that the faithful reproduction of the appearance of a spare part (i.e. including a trade mark as its necessary visual feature or the image of the trade mark reproduced for technical purposesFootnote 68) may be viewed as use of signs or indications that “concern … characteristics of the goods” within the meaning of Art. 14(1)(b) EUTMR (descriptive use). Moreover, a trade mark which is distinctive as such may not be perceived as an indication of commercial origin by the relevant public in this case (non-distinctive use).Footnote 69

In the Opel case, the CJEU ruled out such an interpretation in the case of the faithful reproduction of the Opel logo on miniature models (as, according to the Court, this was not an indication of the type, quality or other characteristics of the reduction models, but merely one element of a faithful reproduction of the original vehiclesFootnote 70). This does not necessarily constitute a critical reading of this limitation in the context of spare parts with a trade mark as a mandatory element. Since the manufacture of spare parts constitutes the faithful and detailed copying of their appearance, in the case of a trade mark that constitutes an integral part of an original part, its reproduction on that part may be regarded as the use of “another characteristic” of the product, as referred to in Art. 14(1)(b) EUTMR, justified by the interest of other operators in competing on the same terms and by the interest of the user of spare parts in having access to a wider choice of such parts.Footnote 71

The perception of the relevant public (i.e. the professionals that purchase the spare parts to make legitimate use of the repair clause) should be decisive in determining whether “the original manufacturer’s” trade mark is perceived as information about the origin of the product or only as information about its features and intended use. Taking into account all the additional duties imposed on manufacturers and distributors of spare parts in terms of providing information,Footnote 72 the origin function of such a mark may effectively be neutralised in an individual case. If, however, in a particular case, the offer of such a spare part with a mark is perceived as indicating that it is either an original part or is manufactured under an OEM (original equipment manufacturer) licence, then there will be no grounds for applying this limitation.

The revised wording of Art. 14(1)(b) EUTMR implies that the use of graphical elements should also be allowed as best describing the characteristics of the goods in a particular case. Changes in modern commercial communication, which is based on images rather than words and often necessitates the use of images to describe the characteristics of goods effectively, should lead to a revisiting of the dogma that only verbal elements can be used descriptively. Duties of diligence imposed on beneficiaries of repair clauses in EU design law, as developed by the CJEU in Acacia, should apply when assessing the condition of use in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial matters.

5 Consumer Understanding

The existence of the repair clause is changing awareness, particularly in the industry and market that has been most affected by the limitation (here: the automotive market). The understanding of both professional users of the repair clause (workshops, retailers, repair stations) and individual beneficiaries (car owners) is changing. Spare parts are recognised for what they are and spare parts buyers usually know what to expect. Accompanying information to the effect that the parts are made and offered by an independent manufacturer and/or seller influences purchasers’ understanding and expectations. In particular, appropriate labelling may neutralise the impression created by the appearance of the trade mark in the context of spare parts commercialisation. The reform of EU design law currently underway, which proposes tying the repair clause to the obligation to adequately inform consumers, will surely only consolidate this. Therefore, general and abstract assumptions about consumers’ perceptions in that context require revision. In many cases, familiarity with the market for spare parts prevents buyers from being misled about the commercial origin of a spare part. Consequently, using an original manufacturer’s trade mark in that context does not necessarily jeopardise the legitimate interests of the trade mark holder or seriously damage the reputation of that mark.

This raises the question of how those changes in consumer understanding may affect individual decisions under trade mark law, which are, after all, normative. The relatively new market situation caused by the introduction of the repair clause, in addition to the particular intertwining of various interests going beyond the binary relationship between the trade mark holder and the infringer in this case result in the need for a more case-specific and concrete assessment of individual circumstances and context-sensitive evaluation.Footnote 73 Extraneous factors (such as the content of the accompanying information and how it is understood by consumers) should be considered in analyses conducted for less typical infringements in cases that are pro-competition and beneficial to consumers and the environment.Footnote 74 The market conditions, actual circumstances and context of trade mark use may influence how the average consumer perceives an individual case.Footnote 75

Concessions to market realities may be the last resort against the rigour of formal protection, which, in an individual case, would lead to disproportionate results. What is striking, however, is the lack of clarity and CJEU guidance as to when, and to what extent, these additional extraneous marketplace factors that go beyond the bureaucratic trade mark infringement test need to be considered.Footnote 76 Therefore, the trade mark limitations framework seems, for the moment, a more appropriate place to consider an empirical perspective.Footnote 77 The assessment of whether use of the sign is consistent with fair practices in industry and commerceFootnote 78 is more open to a plurality of interests than the infringement test. In the infringement discussions, there is much less room to examine how consumers actually perceive the measures taken by competitors to limit the negative effects of using a sign on the interests of the right holder. However, in the absence of appropriate limitations, when required by important supra-individual considerations, it is necessary to let reality and consumer understanding also enter into this stage, which so far used to be subject to rigid formalised rules.

6 Empirical Study

6.1 The Idea of a Survey

The idea for this research was born out of the need to investigate changes in consumer perception of use of the “original manufacturer’s” trade mark in the context of spare parts commercialisation. The study concerned how commercial communications relating to spare parts in the automotive sector, which has benefited the most from the repair clause, were understood. It was conducted in only one EU Member State, Poland, where the repair clause was introduced into design law in 2007.Footnote 79 Moreover, old cars in need of repair dominate the Polish automotive market,Footnote 80 and Polish consumers are not as wealthy as consumers in Western European countries. Many used and damaged cars are still imported from Western Europe; in Poland, after thorough repairs, they are given a “second life”.

The aim was to learn about the perception and judgement of consumers who might actually be interested in buying spare parts for a particular brand of vehicle and be familiar with that brand, i.e. car owners of that brand, and to compare this with the understanding of spare parts professional retailers and repair workshops that make actual use of the repair clause in accordance with its purpose. The study sought to determine how the presence of the original manufacturer’s mark on a part, or in connection with its commercialisation, affects perception of the commercial origin of the spare part and quality expectations. In addition, the survey was designed to examine the impact of trade mark use on perceptions of the quality of the replacement part among the respondent groups surveyed and on their willingness to purchase.

Empirically tested reality cannot be the only decisive factor in the final assessment of an individual situation in trade mark law. In this case, however, the fundamental resistance to and lack of in-depth reflection on the importance of actual consumer perception encouraged us to construct and conduct research. Learning about these realities may be useful when market realities are subject to dynamic changes.

6.2 Method

6.2.1 Participants

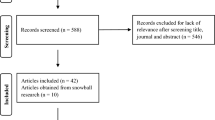

Two studies were conducted on different groups of respondents.Footnote 81 The first study was run online on the purposive sample we arrived at through the portal for automotive professionals, MotoFocus.pl. In this way, we were able to assemble the group surveyed, consisting of 122 professional repairers and retailers, i.e. car service stations (12.3% of the respondents), workshops (50%), spare parts distributors (22.1 %), spare parts stores (8.2 %), and other professionals from the automotive branch, that is a group well oriented in the realities of the market and the spare parts industry, and dealing professionally with spare parts. The study was conducted on Typeform, a web-based platform for creating online surveys.Footnote 82

The second study was run online by the Ariadna Nationwide Research Panel, a Polish counterpart of MTurk, which specialises in polling large samples for the purpose of research.Footnote 83 Purposive sampling was used to reach a group of 172 ordinary car owners; the survey was narrowed down to owners of cars of a specific brand (whose trade mark was an element of the spare part or appeared in the context of spare part commercialisation).

6.2.2 Procedure and Materials

The material presented to participants in both studies resembled typical information available at online auctions. The questionnaire was divided into two parts. Participants were asked to rate an alloy rim in the first part and a grille in the second part, with both spare parts being specifically for selected Audi models.Footnote 84 Next to the graphical presentation of each spare part there was a description of the product. The information included the following data: (1) the name of the product (alloy rim or grille, respectively) and models of car to which it was applicable; (2) the price per unit of the product, which was the average price of a non-original spare part, much lower than the price of the original part; (3) the basic technical parameters: dimensions, the OEM number (i.e. the catalogue number of the original spare part to which the part offered was an equivalent); (4) the additional information that the spare part offered by the trader (a fictitious seller name was given in the survey) reproduced the Community design registered for AUDI AG and was marketed under Art. 110 of EU Regulation No. 6/2002 exclusively for repair purposes. This was followed by the name of the independent manufacturer of the spare part and information about the part’s approval in accordance with UNECE Regulation E11124R-001013, which is relevant for the part’s safety assessment.

The experimental “between-groups” design was used for the studies. Participants were randomly divided into four groups, which varied in the graphical presentation of the spare parts (grille and alloy rim). The first version (Group 1) included a product with a faithfully reproduced original trade mark as an element of the appearance of the spare part. In the second version of the study (Group 2), the replacement parts were devoid of any trade mark as an element of their appearance. In the third version (Group 3), the trade mark appeared as a logo in full graphics and colours next to the spare part which, as such, was devoid of any trade mark. In the fourth variant (Group 4), a trade mark other than the “original”, i.e. the trade mark of an independent spare part manufacturer, was affixed to the alloy wheel. In the case of the radiator grille, however, the last variant related to a spare part with space to mount the car manufacturer’s original figurative trade mark (emblem) that reproduced the appearance of that trade mark. Since radiator grilles with a different trade mark are not offered on the market (unlike in the case of rims and hubcaps), the study also concerned one particular type of spare part, i.e. a grille with space to mount the car manufacturer’s original figurative trade mark. Consumers saw the same general product information in all versions of the study.

Grilles

The following additional product information was presented to all groups tested:

FRONT BUMPER GRILLE AUDI A3 A6

Price per unit: 359 PLN

Description:

Catalogue No. of part: 4F0853651AN

Weight (with packaging): 2 kilos

The grille reproduces the Community Design registered for AUDI AG and is offered by EParts Ltd. under Art. 110 of Regulation EU 6/2002 exclusively for the purposes of repair.

Manufacturer AUTO Parts Ltd.

Alloy wheel rim

The following additional product information was presented to all groups tested:

ALLOY WHEEL RIM AUDI A3 A4 A5 A6 A8

Price per single unit: 599 PLN

Description:

Diameter: 18”

Width: 8”

OEM: 8K0601025CK

The alloy wheel rim reproduces the Community Design registered for AUDI AG and is offered by Eparts Ltd. under Art. 110 of Regulation EU 6/2002 exclusively for the purposes of repair.

Manufacturer WSP Italy.

APPROVAL UNECE R124 E11124R-001013

Most questions in both studies were identical. After being presented with the image of the spare part (according to the variants described above), respondents were asked to rate: (1) the quality of the part; (2) the strength of the material used for the part, and (3) the appearance of the part. Then they were asked whether they would order this part for their workshop/shop or their own car, depending on the group of respondents (4). Finally, the respondents were requested to name a spare parts manufacturer (5). This was framed as an open-ended question to avoid suggesting answers, and respondents could enter any name they wanted. After answering this question, respondents were informed about the true commercial origin of the spare part in line with the general information about the product that had been presented to them in advance. Once in possession of the information pertaining to the actual origin of the product from an independent spare parts manufacturer, respondents were interviewed as to (6) whether, in their opinion, other consumers would recognise that it was not an original Audi part; (7) whether they would recommend this part to other customers; and (8) how they evaluated the quality of the part compared with the original Audi part.

The responses related to quality evaluation were measured on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (“definitely bad”) to 7 (“definitely good”). The answers to other questions (willingness to buy the spare part or willingness to recommend it) were also measured with the Likert scale from 1 (“definitely no”) to 7 (“definitely yes”).

6.2.3 Results

To analyse the results from both studies, a one-way MANOVAFootnote 85 was carried out to compare the effect of different forms of the use of a trade mark in the context of spare parts commercialisation on how respondents rated the parts and how willing they would be to recommend purchasing the parts. The results are presented in Tables 1–4, separately for each spare part type (grille and alloy rim), and split into two studies, with professionals and end users. Identification of the origin of the spare part in all variants surveyed was broken down into respondents who identified Audi as the manufacturer of the part; respondents who identified an independent manufacturer (by name, with variants of names other than Audi appearing here); and those who did not remember who the manufacturer of the spare part was.

Grille ratings by Audi car owners

The analyses showed that differences in rating product quality were not significant in any of the variants. Nor were there any differences in willingness to buy and recommend the part to other consumers (F(18, 458) = .947, p = .962). Regardless of the graphic presentation of the grille, consumers rated this part similarly (even after being informed that it was not a spare part made by Audi). It should also be noted that, in all groups, the part presented was rated relatively high (average above 4 on a 7-point scale). The means for each question are presented in Table 1.

As regards the commercial origin of a grille, the highest level of responses pointing to Audi as the manufacturer of the spare part (although relatively low) was for the use of the original trade mark on the spare part (about 29%) and referential use of a full graphic image of the original mark (37.5%), with an equally high number identifying an independent manufacturer as the source of the spare part. In the case of the Audi logo space, the number identifying the independent manufacturer of this spare part (37%) outweighed that identifying Audi (26%). For end users, the lack of a trade mark on parts reduced the number identifying Audi as a parts manufacturer (16%).

Alloy rim ratings by Audi car owners

Similar to the grille analyses, the analyses for the alloy rim showed insignificant differences in product quality ratings. Nor were there any differences in willingness to buy and recommend the part to other consumers (F(21, 645) = .899, p = .593). Regardless of the graphic presentation of the alloy rim, consumers rated this part similarly (even after being informed that Audi did not make a spare part). It should also be noted that, in all groups, the presented part was rated relatively high (average above 4 on a 7-point scale). The mean averages for each question are presented in Table 2.

When it came to identification of the commercial origin of the alloy wheel by end users, i.e. owners of Audi cars, the situation was similar to that for the grille. A high number identified Audi in the case of the alloy with the Audi logo as an element of appearance (31%), with the highest number in the case of the referential use of the full graphic Audi logo next to the spare part (40%). Interestingly, a relatively high number identified Audi also for the replacement part with an independent manufacturer’s mark (that of WSP) as an element of the appearance of the part (about 24%). Even where there was no trade mark on the spare part, respondents pointed to Audi as the manufacturer of the part (10%), probably based on the verbal description of the purpose of the spare part, which specified the Audi models that the part fitted.

Grille ratings by workshops and professional retailers of spare parts

The analyses of grille ratings by workshops and professional retailers of spare parts showed insignificant differences in how product quality was rated. Nor were there any differences in willingness to buy and recommend the part to other customers (F(21, 322) = .578, p = .932). Regardless of the graphic presentation of the grille, professional retailers and workshops rated this part similarly (even after being informed that Audi did not make a spare part). It should also be noted that, in all groups, the part presented was rated lower than by the car-owner group but still relatively high (average mostly above 3.5 on a 7-point scale). The mean averages for each question are presented in Table 3.

The number of respondents pointing to Audi as replacement part manufacturer was significantly lower than for car owners. An independent spare parts manufacturer was predominantly identified in every variant surveyed (results ranged between about 65% to 80%). Interestingly, regardless of whether or not there was a trade mark on the part, the same number of respondents pointed to Audi as its manufacturer (14%). A relatively low percentage pointed to Audi when the Audi logo was used in a referential way (10%), which shows that the group of professional respondents perceives the presence of this mark in close proximity to the spare part itself differently than car owners do. In the case of grilles with space for the Audi logo, 21% of respondents identified Audi as its manufacturer.

Alloy rim ratings by workshops and professional retailers of spare parts

Similar to the grille analyses, those for the alloy rim showed insignificant differences in product quality ratings. Nor were there any differences in willingness to buy and recommend the part to other customers (F(21, 322) = .761, p = .767). Regardless of the graphic presentation of the alloy rim, professional retailers and workshops rated this part similarly (even after being informed that Audi did not make a spare part). It should also be noted that, in all groups, the alloy rim was rated lower than by the car-owner group but still relatively high (average above 3.5 on a 7-point scale). The mean averages for each question are presented in Table 4.

In the case of the alloy rim, respondents in all variants overwhelmingly identified the replacement part as originating from an independent manufacturer (75–93%). Only in the case of parts with a mark as an element of the appearance of the part did 3% of respondents identify Audi. However, in the absence of a trade mark on the part and in the case of referential use of the full logo of the original manufacturer, none of the respondents pointed to Audi. Interestingly, in the case of an alloy wheel with an independent manufacturer’s trade mark (WSP), almost 11% of respondents pointed to Audi as the product’s commercial origin.

6.2.4 Conclusions from the Study

The study replicated a situation in which an independent manufacturer and seller of spare parts observed the basic rules of “fair play” in the marketplace, informing about a product’s true origin and the repair clause conditions outlined in Art. 110 CDR, in line with the Acacia guidance.Footnote 86 It reproduced the most typical and, at the same time, most controversial cases of trade mark use in the context of the commercialisation of spare parts to which CJEU case-law has already referred or will refer soon.

In the first version, the spare parts reproduced the original trade mark of the car manufacturer, so the product embodied the fundamental problem of using the trade mark as a necessary element of the appearance of the spare part.Footnote 87 The image of the spare part in the second version was utterly devoid of any trade marks. Thus, this was a situation in which the replacement part implemented the guidance of the CJEU judgment in the Ford case, according to which a trade mark cannot be used without permission of its owner.Footnote 88 In the third version, the trade mark (with a graphic logo) of the original manufacturer of the spare part appeared in close proximity to the product (a spare part without a trade mark). The use of the mark in this context was intended to be informative (so-called “referential use” to provide information about the purpose of the spare part).Footnote 89 For the holder of the “original” trade mark, however, it could also be considered as going beyond what was necessary to convey such information, as the full graphical image of the logo was used. In the fourth and final version, the trade mark of the independent manufacturer was affixed to the spare part, slightly changing the appearance of that part; the part was no longer identical to the original one, as in the factual situation of the Acacia case.Footnote 90 In the case of the grille, the study concerned a grille with a space intended for mounting the “original” figurative trade mark (emblem), which, due to its contours, reproduced the outline of the trade mark. A similar situation is at issue in C-334/22, Audi.Footnote 91 These types of parts are also offered on the market for different brands of cars. Users buy the emblem themselves and mount it in the space provided. Unlike with rims and hubcaps, radiator grilles with a different trade mark of an independent manufacturer are not offered on the market.

One of the primary objectives of the study was to see whether perception of the trade mark in these variants (and its effects on quality ratings and willingness to buy and recommend the spare part) differed according to the targeted public for spare parts – professionals, who purchase them to use them for their intended purpose, and end users of the parts, i.e. owners of cars of a particular brand. In general, repairers and professional retailers are highly attentive and aware, being very familiar with what activities are allowed in the field of spare parts manufacturing and trade. They know about the existence of the repair clause in the design regime and about the differences in price and quality between OEM spare parts (those manufactured by original equipment manufacturers), OES spare parts (those manufactured by official equipment suppliers) and IAM parts (those manufactured by independent aftermarket manufacturers). The latter, if they reproduce a Community design, are offered only to professional repairers. The number of customer complaints that professionals receive usually highlights differences in quality. Meanwhile, knowledge and understanding of market messages by end users of spare parts can differ significantly, as such users do not usually replace a spare part themselves, but rather contract professionals to do so, relying on information about the origin, price and quality of the part provided by the repair garage or auto service station.

The results of the study confirm some noticeable differences in both identifying the commercial source of the parts and rating their quality. Regarding the first issue, the questions sought to establish how respondents understood the commercial source of goods and whether the trade mark used in this context functioned as a source identifier or whether its origin function was neutralised. The variants in use or lack of use of the “original” trade mark were to test how its presence in a particular form or its absence might affect how product origin was perceived.

End users – i.e. Audi car owners – were more likely than professional dealers and workshops to be misled about the origin of spare parts in virtually all variants. Still, the percentage pointing to AUDI was relatively insignificant. The number of respondents pointing to AUDI as the manufacturer visibly increased when a figurative trade mark appeared on or around the spare part. Professional retailers and workshops, on the other hand, showed almost no propensity to be misled as to origin – the percentage indicating AUDI as the manufacturer of these parts was almost identical both when the part was offered without the mark and when the trade mark appeared on the part or was used for referential purposes. This might lead to the conclusion that professionals perceive the trade mark of the original manufacturer of a spare part in the context of the sale of independently sourced spare parts as a description of characteristics of the goods (especially its purpose) rather than as an indication of origin. Overwhelmingly, professional parts sellers indicated that the part (in all variants presented) came from an independent source. For car owners, more responses suggested that they did not remember who the manufacturer of the replacement part was, despite a clear hint to that effect in the product description presented.

As regards the second aim of the study, i.e. quality ratings and willingness to buy or recommend the part, quality expectations were presumed to vary depending on the method of use of the “original” trade mark. Meanwhile, the results are fairly similar in terms of the part’s quality rating and the level of willingness to buy regardless of the type of trade mark use in the context of the commercialisation of the replacement part. This reveals a certain level of immunity to the presence of the original car manufacturer’s trade mark. In both groups, spare part quality ratings did not significantly deteriorate once the respondents were informed of the actual origin. The ratings are slightly lower for car owners, confirming their greater bias in favour of spare parts that originate with the original car manufacturer. These results may provide useful information for assessing whether other trade mark functions, mainly those relating to quality and investment, are seriously jeopardised by use of a trade mark in the context of the commercialisation of spare parts; they show that it is difficult to see such an impact in this case.

The purpose of the research was not to provide purely empirical arguments to resolve specific cases of trade mark use in the context of spare parts commercialisation. Nor do we believe that trade mark adjudication should be based on purely empirical inquiries. However, its results might serve as a starting point for broader debate about trade mark policy in the context of an important issue and inspire valid normative considerations leading to a revision of selected rigid concepts and apodictic assumptions in trade mark law, with the ultimate goal of leading to normative decisions that take into account, above all, the objectives, values and interests that come together in an individual case. The context of spare parts and the right to repair provides a solid normative argument for the necessary revision and expanded perspective.

7 The Polish Court Referral in Case C-334/22, Audi

The District Court in Warsaw (Intellectual Property Law Department) recently referred questions relating to the issues mentioned above to the CJEU.Footnote 92 The articulation of these questions is quite controversial and hopefully will not prevent the CJEU from resolving key issues of major practical importance. In C-334/22, Audi, the national court asks whether Art. 14(1)(c) EUTMR must be interpreted as precluding a trade mark owner/court from prohibiting a third party from using, in the course of trade, a sign identical or confusingly similar to an EU trade mark, in relation to spare parts (radiator grilles), where the sign concerned constitutes a mounting element for a car accessory (an emblem reproducing the EU registered trade mark). The court suggests to consider two scenarios independently: (1) where it is technically possible to affix an original emblem reproducing an EU trade mark to a spare part for a car (radiator grille) without reproducing on that part a mark that is identical or confusingly similar to the EU trade mark; and (2) where it is technically impossible to affix an original emblem reproducing an EU trade mark to a spare part for a car (air radiator cap/grille) without reproducing on that part a mark that is identical or confusingly similar to the EU trade mark. The court asks further what criteria should be applied to determine whether use of an EU trade mark is consistent with honest practices in industrial and commercial matters.

Next, the Court touches upon trade mark infringement criteria. It asks whether Art. 9(2) and Art. 9(3)(a) EUTMR should be interpreted as meaning that, in the absence in the EUTMR of a repair clause equivalent to that provided in Art. 110(1) CDR, a trade mark included in the shape (appearance) of a spare part does not perform the function of indicating the origin of the goods. The Court also asks whether, in such a situation, the affixing element cannot be regarded as a trade mark performing a distinguishing (origin) function even if it is identical to the trade mark or confusingly similar to it.

In the case referred, the plaintiff requested that the defendant be prohibited from importing, offering, marketing and advertising radiator covers (“grilles”) that did not originate from AUDI AG and bore a sign identical or similar to European Union figurative trade mark No. 000018762, registered for goods in Class 12 of the Nice Classification (vehicles, spare parts, automotive accessories).

The defendant is a professional retailer of spare parts for cars. It sells products (including radiator grilles for old Audi models from the 1980s and 1990s) to other businesses (professional sellers, distributors) and does not offer them direct to consumers. The radiator grilles include a space for mounting the car manufacturer’s original figurative trade mark (emblem) that reproduces or resembles the outline of the applicant’s trade mark.

The defendant sought to maintain its high ranking in the automotive spare parts market in Poland and to ensure the sale of particular types of parts (e.g. exterior body parts) for all possible models (including older models and those that were virtually disappearing from the market). During the trial the defendant referred to the common practice among car manufacturers (including leading automotive companies) of not opposing the sale of grilles (radiator covers) that include a space that resembles the original emblem but also allows the original emblem to be mounted (numerous photos of such grilles produced for various brands were presented to the court).

The national court settled the problem of using a trade mark as a necessary element of a spare part in the referential use defence, as provided in Art. 14(1)(c) EUTMR. This move may bring about CJEU guidance on the meaning of the recent amendments to Art. 14(1)(c) EUTMR, which allows the use of a mark in the course of trade to identify or refer to goods or services as those of the proprietor of that trade mark, in particular where the use of that trade mark is necessary to indicate the intended purpose of a product or service, in particular as accessories or spare part. As a result of trade mark law reform in Europe, the scope of limitation for referential use in Art. 14(1)(c) EUTMR has been significantly extended to all forms of reference to the goods or services of the trade mark owner, even for unspecified informative purposes, including, for example, to provide information about an alternative product.

Before amendment, use of a trade mark for referential purposes was limited to “where it was necessary to indicate the intended purpose of a product or service, in particular as accessories or spare parts”.Footnote 93 With regard to that former wording, the national court, in the Gillette case,Footnote 94 raised the issue of whether the permissibility of referential use of a trade mark should be assessed differently, depending on whether the product constituted a spare part or accessory or was used for other referential purposes. In Gillette, the CJEU ruled that “[t]he criteria for assessing the lawfulness of the use of a trade mark with accessories or spare parts in particular are thus no different from those applicable to other categories of possible intended purposes” of the products.Footnote 95 Moreover, in the Gillette case, the criterion of “necessity” was fleshed out as use that “in practice constitutes the only means of providing the public with comprehensible and complete information on that intended purpose in order to preserve the undistorted system of competition in the market for that product”.Footnote 96

However, the new wording of 14(1)(c) EUTMR highlights the issue that referential use may also be for different purposes, for which more relaxed criteria apply.Footnote 97 In many cases, a particular form of reference is the one that is needed, useful and efficient but, at the same time, not absolutely necessary to inform consumers.Footnote 98 In the past, courts rarely accepted such “less necessary” references as legitimate.Footnote 99 The rapid change of customs and practices in commercial communication should be taken into account when assessing which communication tools are considered both necessary and justified as honest commercial practices.Footnote 100 The dominance of images over text in modern market communications makes it essential to revise the dogma that only referential use of the verbal version of a trade mark is legitimate.Footnote 101

In the Audi case, the CJEU will have to first answer the question of whether the particular use of the trade mark as an element of a spare part constitutes a referential use under the new wording of the provision. This case may also present the CJEU with an opportunity to revisit the role of the "necessity" criterion. In the context of spare parts, a faithful reproduction of the appearance of the replacement part is certainly necessary for it to fulfil its function properly. While there are reasons to consider this use as a referential one,Footnote 102 it is regrettable that CJEU was not also prompted to assess whether it is a descriptive and non-distinctive use under Art. 14(1)(b) EUTMR (see the discussion in Section 6 above).Footnote 103

The national court raised the issue of criteria for evaluating whether use complied with honest practices. Interestingly, the court referred to the established and proven practice on the automotive market of offering radiator grilles with spaces for mounting an emblem (trade mark).Footnote 104 Such market customs can undoubtedly influence consumer expectations and understanding. In the court’s view, however, it would not be appropriate for market customs and common practice to be a source for delimiting the scope of an exclusive right.Footnote 105 The court seems rather sympathetic to the view of the normative nature of this assessment and points out the need to balance the interests of the trade mark owner with those of independent spare parts manufacturers, considering the scope of information provided to potential buyers about the origin of the parts.Footnote 106

Nonetheless, this referral gives the CJEU room to elaborate on the criteria for interpreting Art. 14(2) EUTMR. So far, the reference points have been the three established categories of commercial tort, i.e. suggesting a commercial connection, denigrating or discrediting, and taking unfair advantage of distinctive character or repute.Footnote 107 This case offers an opportunity to abandon the harmful post-Gillette dogmaFootnote 108 that where a third party presents a product as an imitation or replica of an original product bearing a trade mark of which it is not the owner, such use of the trade mark does not comply with honest practices. Spare parts, by their nature, are imitations and replicas, and offering them cannot be unfair for this reason alone. The unambiguous position adopted by the CJEU on this issue, eliminating this nonsensical condition for products that are legitimately offered as imitations, could be highly relevant also in the context of an analogous controversial requirement for fair comparative advertising.Footnote 109

In addition to giving good reasons for referring to trade mark right limitations, the defendant questioned whether there had in this case been use of a trade mark as described in Art. 9(2) EUTMR. He pointed out that the element of the radiator grille for Audi cars – that is, the place for attaching the chrome emblem – had only a technical function, which was perceived as such by the average, rational and observant consumer. The shape of the space for mounting the emblem embodying the car manufacturer’s trade mark was not perceived by recipients as an indication of origin of the goods but rather as a necessary element of any spare part that is intended to enable the repair of the vehicle by restoring its original appearance.

The referring court raised doubts as to whether a trade mark affixed to the appearance of a spare part (in the way presented above) performed the function of indicating the origin of the product in this particular case. Moreover, it asked whether trade mark rights could undermine the pursuit of undistorted competition and the consumers’ interest in being able to choose between buying an original or a non-original auto part in a situation where it is legal in itself to offer such non-original parts for sale.Footnote 110 For the national court, an interpretation that thwarts the principles of competition by making trade mark law a mechanism for blocking the production of non-original parts would be incorrect.

According to the national court, this problem can already be resolved when no use as a trade mark is found. However, should the CJEU not share this view, the discussed use would, in the view of the national court, fall within the limitation described in Art. 14(1)(c) EUTMR. This would be the case also if, from a technical point of view, it was possible to mount the original emblem with the trade mark on a car spare part without reproducing an identical or confusingly similar mark on that part. Otherwise, the idea of liberalising the market for spare parts, which by their very nature must be compatible with original parts, would be lost.

8 Conclusion

In the EU, R2R has acquired critical environmental support and has imposed solutions (including the mandatory repair clause in the EU design regime) that had hitherto been hardly accepted by the Member States. R2R has significantly broadened the range of interests to be considered in the balance-seeking approach, in many cases supplementing free competition arguments with those relating to sustainability and circularity. There remains to be an in-depth discussion of the significance of these horizontal changes for intellectual property protection (including trade mark law, which seemingly presents itself as distant from these issues).

The studies presented above show that certain assumptions that have so far resulted in rather apodictic decisions in trade mark law need to be revisited in view of the dynamic changes that have taken place. Certainly, the shift in the economy towards circularity should not undermine the essence of trade mark protection. Instead, the current situation, strongly marked by social interests of the utmost importance, might necessitate revisiting the heart of modern trade mark protection, and especially reviewing doctrines based on apodictic, hypothetical, and abstract assumptions that diverge from reality.Footnote 111 The normative question that needs to be addressed in this context is whether trade mark law should control the market for spare parts in the case where a limited negative impact on trade mark functions is established and the conduct conforms with principles of undistorted competition and sustainability.

Thus, one issue will definitely change – competition arguments will go hand in hand with sustainability arguments. This will certainly reshape the face of trade mark protection and other intellectual property regimes. Indeed, the changes that are unfolding in the economy and the market as a result of the shift to a circular economy will require keeping abreast of changes in consumer behaviour. After all, this transformation aims to change such behaviour. If trade mark law remains impermeable to these needs and changes, it will constitute a significant obstacle to the full implementation of sustainability policy.

Notes

Kur (2021), pp. 228–236.

Pihlajarinne (2021), pp. 92–97.

The issue raised already by Tischner (2021), pp. 397–402.

See e.g. the Norwegian Supreme Court judgment of 2 June 2020, HR-2020-1142-A, (case No. 19-141420SIV-HRET), Henrik Huseby v. Apple Inc (English translation available at: https://www.domstol.no/globalassets/upload/hret/decisions-in-english-translation/hr-2020-1142-a.pdf), discussed by Rognstad (2021), pp. 101–114.

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions of 11.3.2020, COM(2020) 98 final, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/circular-economy/pdf/new_circular_economy_action_plan.pdf.

Communication from the Commission on The European Green Deal, COM (2019) 640.

Directive (EU) 2019/771 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2019 on certain aspects concerning contracts for the sale of goods, OJ L 136, 22.5.2019, p. 28.

CEAP (supra note 5), para. 2.3, p. 8: “Empowering consumers and providing them with cost-saving opportunities is a key building block of the sustainable product policy framework. To enhance the participation of consumers in the circular economy, the Commission will propose a revision of EU consumer law to ensure that consumers receive trustworthy and relevant information on products at the point of sale, including on their lifespan and on the availability of repair services, spare parts and repair manuals.”

Art. 11 TFEU: Environmental protection requirements must be integrated into the definition and implementation of the European Union’s policies and activities, in particular with a view to promoting sustainable development.

Art. 37 of the EU Charter: [Environmental protection] A high level of environmental protection and the improvement of the quality of the environment must be integrated into the policies of the European Union and ensured in accordance with the principle of sustainable development.

Directive 2009/125/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 establishing a framework for the setting of ecodesign requirements for energy-related products (recast). On 1 March 2021, the new EU mandatory ecodesign measures on repair for selected appliances (i.e. washing machines, dishwashers, fridges and displays, including TVs) came into force in Europe to make such appliances more easily repairable and longer-lasting. However, the new regulations apply only to models put on the market after 1 March 2021. The measures address the problems of repair-friendly product design, access to spare parts and repair information (which is limited to professional repairers and should be available for 7–10 years), as well as the delivery deadline for spare parts (long delivery time – 15 working days). See also the European Commission Proposal of 30.03.2022 for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council establishing a framework for setting ecodesign requirements for sustainable products and repealing Directive 2009/125/EC, COM(2022) 142 final.

Cf. European Parliament resolutions of 25 November 2020, Towards a more sustainable single market for business and consumers (2020/2021(INI)), and of 10 February 2021 on the New Circular Economy Action Plan (2020/2077(INI)), as well as a proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directives 2005/29/EC and 2011/83/EU as regards empowering consumers for the green transition through better protection against unfair practices and better information, COM (2022) 143.

CEAP (supra note 5), para. 6.3.

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions of 25.11.2020, Making the most of the EU’s innovative potential. An intellectual property action plan to support the EU’s recovery and resilience, COM/2020/760 final.

With reference, however, to the relevant requirements under the ecodesign implementing regulations introduced in October 2019, i.e. C(2019) 2120-7, C(2019) 5380, C(2019) 6843.

IP Action Plan (supra note 15), para. 2.