Abstract

Like most private enterprises, the pharmaceutical industry has deeply rooted environmental, social, and governance (ESG) matters that challenge its long-term sustainability. Overcoming these external challenges requires collaborative and proactive steps as well as procedures guiding the adoption of ESG principles by all internal stakeholders. Environmental challenges such as climate change, and in addition the changes in society, have resulted in the need for governance addressing and coordinating efforts. The core function of medical affairs (MA) is connecting with stakeholders within a company and also between the company and external stakeholders. In this article, we describe the involvement of MA in several aspects of ESG, as a contributor, partner, and implementer. MA has a significant opportunity to emerge as a leading function involved in ESG strategies and their tactical implementation. Although the involvement of MA in the environment pillar of ESG is less, the function can implement changes relating to the conduct of meetings, clinical studies, and the digitalization of medical education via virtual platforms. Due to its patient centricity, MA is tasked to address social determinants of health to improve patients’ outcomes. As a linking function within a company and with its external stakeholders, MA can provide proactive input in policy generation and enable effective governance by adherence to standards of accountability, ethics, and compliance, as well as transparency. Championing ESG is a collective responsibility that transcends any single department. It mandates a company-wide commitment. MA represents an essential pivot point in catalyzing the integration of ESG principles within industry, contributing to a healthcare ecosystem that is not merely more sustainable and ethical but also more conducive to patient health and public well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Environment, social, and governance (ESG) engagement has shown to support a pharmaceutical company’s adaptability, and therefore secures mid- and long-term financial health. |

Establishing and implementing ESG principles is a complex task and requires strong cross-functional involvement from a function that performs with agility in a matrix environment. |

The medical affairs (MA) function is to contribute to ESG strategies due to its ‘bridging’ function within pharmaceutical organizations and the alignment with its core imperatives of patient centricity, credibility, and adherence to compliance. |

The transformation of MA from an enabler to a strategic leader carries a significant potential to be integrated in ESG strategies and to assume responsibility for ESG initiatives and values, underpinning industry’s sustainable and ethical operations with future implications for patient health and public well-being. |

1 Introduction

ESG (environmental, social, and governance) is a broad taxonomy that guides an organization’s operations and informs about a company’s beliefs, objectives, and risks [1, 2]. ESG has become an increasingly important consideration for enterprises because our planet is facing environmental challenges, such as climate change, because of an increasing awareness of social issues, such as inequality and human rights, and because of governance issues, such as corruption and corporate transparency [3]. ESG factors affect the performance and activity of businesses and are assessed financially for investment decision making and performance [4, 5]. The importance of these ESG indicators has been amplified in recent years in an increasingly globalized environment. For example, in 2019, 90% of the 500 biggest companies listed on the United States (US) stock exchanges (S&P500, Standard and Poor 500 Index, a widely used equity market index, tracking the stock performance of companies not limited to US entities) report ESG disclosure, representing a substantial increase from 20% in 2011 [6].

ESG is recognized as highly relevant to do sustainable business, and in several jurisdictions the reporting of ESG is either mandated or under consideration, such as by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) [7]. While this is an important step forward, several challenges in the implementation of ESG need to be addressed [8]. The environmental dimension of ESG is intricately linked with health outcomes. Factors such as pollution and climate change contribute significantly to various health problems, thus highlighting the urgency for an environmentally conscious ethos within healthcare [9]. Simultaneously, the social aspect, addressing social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status and healthcare access, is critically influential in shaping health outcomes [10]. Robust governance practices, encompassing transparency, accountability, and ethical conduct, are integral to preserving trust in the healthcare sector [11].

In this current opinion article, we focus on the pharmaceutical and biotech industry, which has been called out for ESG issues, challenging sustainability, requiring it to address environmental and social challenges through effective governance policies [12]. Clear, broadly accepted and especially cross-company comparable key performance indicators (KPIs) are needed to measure effectiveness of implementation of ESG and effective communication [13, 14]. This requires collaborative, proactive steps to adapt environmental and social tasks of governing policies by all internal and external stakeholders.

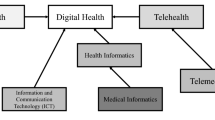

Medical Affairs (MA) acts as a connector with a variety of functions within a pharmaceutical company [15]. It is the function that appears most often as a key stakeholder in cross-functional matrices. As such, MA is well positioned to ensure implementation of ESG actions it is involved in (Fig. 1). Furthermore, MA has a central role in the establishment and maintenance of connections between the organization and external stakeholders such as health care professionals [15, 16]. This unique situation puts medical affairs in a strategically relevant position to also lead ESG initiatives and work cross-functionally to develop processes, policies and metrics to track progress. Due to the strategic, long-term impact of ESG, MA should be consulted and involved when ESG actions are evaluated and new policies are issued (Fig. 2).

Illustration describing the four archetypes for ESG-compliant activities based on the ease of implementation and scope for medical affairs’ functions. Overall, all activities demand patient centricity while still balancing the organization’s interests and enabling the maximum level of profitability. Medical affairs is generally an enabling function for most of these activities; however, it is the leader in optimizing ESG principles for medical initiatives. The correct decisions across all activities require establishing and adherence to an adequate ESG policy. In line with the research by Wollensack et al. [108], we use the term defossilization to describe the substitution of carbon-based raw materials (organic compounds) produced from materials of fossil origin by renewable stocks in the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals. ESG environmental, social, and governance, CUP compassionate use program, M2M medical-to-medical, RWD real-world data

2 Medical Affairs’ Involvement in ESG Initiatives: An Overview

MA is involved in several areas relating to ESG where direct influence can be exerted and responsibilities assumed, carrying the potential for corporate integration of the function to be included in ESG strategies. These areas are depicted in Fig. 1 and will be described in more detail in the subsequent sections for each determinant of ESG.

2.1 Environment

The impact of global warming necessitates a heightened focus and sense of urgency on the environmental impact of the pharmaceutical industry [17]. The US has the second highest carbon dioxide (CO2) emission in the world, after China and followed by India, Russia, and Japan [18]. On 27 January 2021, the White House issued an executive order to tackle the climate crisis at home and abroad, highlighting a narrow window to prevent the most dramatic impact of the climate crisis, which was followed by the Inflation Reduction Act in August 2022, setting an ambitious target for greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction and drawing the attention on the importance of environmental sustainability across different industries [19, 20].

2.1.1 Environmental Responsibilities of Pharmaceutical Companies

Pharmaceutical companies focus their environmental efforts on several pillars. To reduce and ultimately achieve net neutrality in direct and indirect GHG emissions through focus on renewable energy resources, reduce and achieve zero waste to landfill through recycling, use of products made from recycled material, equitable water use, and convert to an electric vehicle fleet [13].

It should not be forgotten that the use of electric vehicles alone is not sufficient to reduce GHG emissions. It does matter which source the electricity for said vehicles comes from, thereby highlighting the importance on renewable energy sources [21]. Furthermore, energy-saving measures for company infrastructure, such as energy-efficient buildings, e.g., via improved insulation, low energy-consuming lights such as LED lights, reduction of air-conditioning through automatic shades, and a highly effective supply chain using as little packaging material as possible, are some of the initiatives taken by companies [13].

Travel, especially air travel, comprises the biggest part of the environmental impact of companies’ activities. A recent study investigating industry congress travel of a mid-sized pharmaceutical company demonstrated that carbon emissions associated with in-person attendance resulted in 182 times the average emission per attendee compared with virtual attendance (mean 1893.5 kgCO2e vs. 10.4 kgCO2e), mainly due to air travel [22]. Reducing the requirement for air travel would be a first step towards reducing the carbon footprint. Looking for venues that can provide other options for travel (e.g., via trains) and selecting locations that are closer to participants and provide opportunities for virtual attendance are potential solutions [23]. Incorporating geography into the meeting location selection process and alternating large national-level meetings with smaller regional meetings may also reduce the environmental impact of medical meetings [24,25,26].

Reducing the environmental impact of travel refers not only to medical meetings but also field MA activities. Reducing the number of flights, encouraging the use of public transport and company policies for the purchase of hybrid or electric vehicles for field medical personnel (e.g., ‘Green Fleet’ programs) can efficiently reduce the environmental impact [27].

Besides travel, there are other ways to make MA activities, including events and other stakeholder engagement activities, more sustainable. Any educational event must be planned carefully, and venues with good recycling and emission reduction programs (including green-energy purchases) are preferred [27, 28]. Sustainability also applies to food and beverage choices, the use of carefully selected local and seasonal products, the reduction and supplementation of beef meat and dairy products. Beef production in particular is emission intensive, and beef has one of the largest GHG footprints among food products [29]. Reducing and replacing meat with vegetables and salad decreases food waste and also make meals less calorie-intense and decreases the risk of several non-communicable diseases, such as overweight, diabetes, coronary heart disease or cancer [30]. Smaller servings, as well as local produce and vegan or vegetarian meals, reduce food waste and reduce GHG emission due to the proximity of the food source [27, 31, 32].

2.1.2 Virtual Meetings and Massive Open Online Courses

The number of conferences with new formats is on the rise [33]. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic prompted event holders to move conferences online. Virtual and hybrid conferences are greener alternatives to in-person conferences. A recent study found that moving from face-to-face to virtual events can decrease the carbon footprint by 94% and energy use by 90% [28]. However, an exclusively online format may result in lower involvement from participants and participation at conference social events [34]. Selected hubs for hybrid conferences may overcome reduced virtual engagement and have a potential to slash carbon footprint and energy, with spatially optimal hub selection reducing carbon footprint and energy consumption by 60–70% while maintaining 50% virtual participation [38].

High-level continuous medical education (CME) is essential to achieve optimal patient outcomes [15, 35]. As webinars are the most common forms of virtual CME activities, there is also a trend for massive open online courses (MOOCs) that have the functionality for learners to ask questions, discuss data and different practices, and network with fellow learners, therefore having a great potential to reduce the number of carbon-intensive live educational activities [36].

2.1.3 Increase Sustainability of Clinical Research

According to the Edinburgh Centre for Carbon Management, in the case of clinical studies, the carbon emission associated with clinical research may add up to 14 tons per employee involved each year compared with the 4–5 tons average among service industries [37].

An example to illustrate the impact of a clinical study on carbon emissions is the CRASH trial, which was conducted in 49 countries and required a complex drug distribution protocol [38]. In CRASH, total carbon emission was estimated for 1 year according to the World Business Council for Sustainable Development criteria [39]. During the audit period, 126 tons of GHGs (CO2 equivalents) were emitted. The main sources of energy use were the coordinating and research premises and air travel related to drug dissemination and business travel [37]. The CRASH study highlights the importance of manufacturing facilities and coordinating centers in the environmental impact of the clinical development process.

There are several options to reduce the environmental impact of clinical trials. Foremost, companies should avoid the collection of unnecessary data—sound justification is necessary for any new research activity. It is important to employ the minimally necessary study personnel and reduce unnecessary bureaucracy. Simple study protocols may reduce the need for site visits and building a local capacity and a network of triallists may also reduce the need for onsite training. Videoconferences/telemedicine and electronic remote data collection have also demonstrated environmental benefit [37, 40].

The role of MA has evolved to become an integral part of the drug development process, ranging from proof-of-concept to lifecycle management of a pharmaceutical [41]. As such, the MA function is no longer limited to postmarketing observational studies, and by being integrated into study designing and protocol development of clinical trials, has an opportunity to influence environmental considerations.

2.2 Social

The social pillar is a traditional key focus for pharma and healthcare companies, given their high degree of social responsibility to the public through the products made available to treat illnesses [42]. According to an analysis of 32 pharma and life science companies’ websites and 90 press releases between 1 January 2020, and 15 April 2021, 77% of pharma ESG efforts were social-related priorities, while just 12% were environmental and 11% were governance [43, 44].

MA plays a role in pharmaceutical enterprises when it comes to social responsibility and social-focused activities. This is because of several strategies the function is driving or heavily involved in, such as patient centricity, evidence generation to enable affordable access to medicines across markets, compassionate or special access programs, equitable participation in clinical trials, grants, and support programs, among others. In the ESG section of its 2022 published white paper on The Future of Medical Affairs 2030, the Medical Affairs Professional Society (MAPS) calls for medical teams “addressing the social determinants of health to broadly improve patient outcomes” [45].

2.2.1 Guided by Patient Centricity

A shift from a product focus to a patient focus, and adaptation of more patient-centric business structures and processes has become increasingly imperative for the pharmaceutical industry [46]. The change from a disease-centered to a patient-centered mindset and from a product-led to a patient-led development approach has been advocated previously by MA professionals as a necessary shift in cultural mindset in the modern business environment [47]. With the growing importance of patients and consumers as stakeholders, so has the MAs’ role in ensuring patient centricity is at the forefront of any initiative the industry undertakes [15].

Understanding and involvement in the patient journey, collaboration with patients and patient organizations through medical communication, evidence generation, and collaborative engagement of patients and associated family and care partners to support medical product development have become pillars of MA activities [48,49,50]. Similarly, in clinical research, patients are considered informed collaborators whose participation is ‘core’ to the overall success of trials [51]. In the concept of patient-centered drug development, patients play a pivotal role in all phases of drug development, where patient perspectives are considered throughout targeted product profiles, product design, study planning, design, and execution, as well as evidence reporting, knowledge translation and dissemination [47, 52, 53]. Patient-centered drug development also means including patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and other humanistic parameters in clinical development, and particularly in the earlier stages than the latter routine real-world/postmarketing settings. The benefits of early clinical phase inclusion of PROs go beyond complementing conventional efficacy and safety data; they are an opportunity to inform regulatory approvals, health policy, and clinical guidelines, to enhance future PRO strategies and future sample size calculations, as well as to provide preliminary efficacy data based on the patient experience and can help guide improvements in future clinical care [54].

In summary, MA activities are guided by patient centricity. This makes the functions valued partners primarily with external healthcare professionals since a common interest is shared.

2.2.2 Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in Clinical Research

In its April 2022 guidance on Diversity Plans to Improve Enrolment of Participants from Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations in Clinical Trials Guidance for Industry, the US FDA aims to enhance the diversity of clinical trial populations by recommending Race and Ethnicity Diversity Plans from sponsors of clinical trials seeking an investigational new drug or a biologics license application [55, 56].

In addition to clinical trial data generation, PROs need to be inclusive and equitable. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is set to recommend the advancement of standards for clinical studies incorporating robust and meaningful patient experience data for regulatory submission [57, 58]. PROs are an important tool to demonstrate patients’ health-related quality of life, and the inclusion of underserved populations in PRO measures and data collection reflective of diverse and multicultural societies will improve research and promote equitable healthcare for the benefit of all patients and the broader public [59].

MA can ensure, via effective communication and its cross-functional involvement, that the advantages of diversity in clinical trials are understood and considered within organizations. In early study phases, diversity of trial subjects may improve the accuracy of key stop/go decisions and thus avoid later-phase studies on ineffective treatments, leading to cost savings. In addition, diverse patients enrolled may be more engaged and committed to staying in the study; thus, they could be followed up long-term, either in later trial phases, extensions, or real-world studies. Lastly, diversity will also result in an engagement opportunity for industry with investigators, research sites, patient advocates, and underrepresented communities [60].

2.2.3 Enabling Access to Medicines

Due to the challenges of managing increasing public health care expenditure, demand for evidence and justification of value are increasingly a requirement across global markets to support government funding and reimbursement decisions or price negotiation about new medicines and health technologies [61, 62].

The data-generation strategy has shifted here to an integrated approach that considers evidence required by payers in earlier clinical stages of development [63]. In particular, PROs and other real-world evidence (RWE) parameters generate value-based outcomes. These are regularly used in economic modeling and when establishing pricing for new therapeutic interventions, and as such are relevant to a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) by which payers judge if a new drug is cost effective in their healthcare system [64].

Evidence generation, and especially RWE generation, are core to the MA function, mostly in close alignment with market access/health economics and outcome research (HEOR) and other relevant functions (epidemiology, pharmacovigilance, etc.), ensuring the voice of the patient is heard and incorporated into evidence generation while simultaneously improving the standard and rigor [15, 65].

Access to unlicensed or otherwise unavailable or inaccessible (e.g., unfunded) potentially life-saving medicines through compassionate use programs (CUP), early access programs (EAPs) or other special access schemes, is usually governed and supervised by the clinical development and MA functions [65, 66]. Despite various individual country-specific regulatory differences in the set-up, these programs and clinical trials generally provide free-of-charge prelaunch access to unapproved drugs [67]. The programs allow the companies and physicians to meet the needs of patients with serious or rare diseases by providing potentially life‑saving medicines via a controlled mechanism of access and may generate additional value via the development of positive relationships with key opinion leaders (KOLs), patients, and regulators [68]. This can build an advocacy base for the product and provides an opportunity for early penetration into the market during pre-launch, as well as increased acceptance and uptake by physicians and patients after the commercial launch of the product [69, 70]. Finally, MA can proactively generate meaningful, RWE from such programs, despite their inherent challenges (lack of standardization, heterogeneity, confounding variables, etc.) [71,72,73,74].

2.2.4 Grants and Support Programs

Requests and applications for medical education grants, research grants, charitable contributions, funding support and other support programs are usually assessed and approved by MA within the compliance framework and other applicable guidelines and policies [15, 75]. Educational grants are given to support bona fide activities, ensuring independence, and decoupling from objectives related to product sales and promotion, whereas research grants are not only direct funding but can also constitute supply of a company’s product free of charge or other support for the purpose of advancing knowledge via evidence generation [76]. Financial support enables health care organizations and patient advocacy groups to grow their operations, cover administration costs and pursue activities such as education, research funding and advocacy [77]. Charitable contributions and business donations range from disaster relief to providing community medical services, improving the quality and availability of healthcare [78].

Those contributions serve additional beneficial purposes for the industry, such as collaboration with researchers, academia and health care organizations, product enhancement through additional evidence generation, disease awareness, etc. Industry contributions not only support the advancement of research and innovation but also have broader merit towards public health and healthcare infrastructure, as companies are involved in actions that consider the well-being of society [42]. Favorable public views of these activities have been reported among US consumers in 2020, with 62% stating they would view an organization more positively if it takes action to address social determinants of health—essentially actions in the social pillar of ESG [44].

2.3 Governance

The pharmaceutical industry governance model links business considerations with its ESG framework and ensures engagement and alignment from senior leadership with its cross-functional governing committees and independent oversight. Leadership commitment on governance focuses on aspects related to business ethics, promotional practices, anti-bribery and anti-corruption, integrity, compliance, gender diversity, quality framework and standards, and, among others, a commitment to patient safety [78,79,80,81,82]. However, adequate, and effective corporate governance has been called out for higher disclosure quality and transparency [83].

The MA function ensures adherence to standards of accountability, ethics, and compliance, as well as transparency. This is done through core MA competencies that can withhold audit scrutiny in policy governed areas of external engagements (non-promotional), medical information query resolution, review of promotional activities and grants, ensuring the quality use of medicines, conduct of clinical research, and transparency reporting [15, 65, 84].

2.3.1 Quality Use of Medicines

From the experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic, medicine accessibility and supply were challenged globally, putting patients’ lives at risk [85,86,87]. During the pandemic, the use of experimental medicines has not been uncommon, be it the repurposing of established drugs, off-label use or compassionate requests, yet only MA can respond to unsolicited off-label enquiries as per common governance [15, 16, 88, 89].

Well-recognized gaps in the prescription and use of medicines, for example high prescribing rates of antibiotics leading to antimicrobial resistance, or opioid prescribing with insufficient restrictions resulting in misuse and addiction, have led to initiatives aimed at quality use of medicines, improving the standards of prescribing, and taking proactive measures to ensure medicines are used correctly in the right patients. Within the industry, the quality use of medicines is ensured by MA in collaboration with other functions. Here, the leading role of MA is to ensure proper and safe use of medicines through medical education, via ensuring information to the external audience is accurate, balanced, and substantiated, initiatives to improve patient adherence and persistence, for example, via patient support programs or patient and caregiver education, and lastly, via meaningful data generation as a fundament for these activities. Taking antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) and industry’s role as an example, MA provides AMS awareness and education, facilitates research and AMS surveillance (especially via global programs for identifying resistance trends), facilitates patient-centered AMS program implementation, generates treatment decision support tools, and establishes advocacy with infectious disease societies, patient groups, and other partners to enable appropriate patient access to novel antibiotics [90].

2.3.2 Continuous Medical Education

CME under the governance of MA results in better clinical outcomes for patients and improved physician performance, and thus linking the provision of such back to patient centricity [91,92,93]. Principles of quality-based medical education range from ethical, transparent and responsible engagement to needs-based, up-to-date, balanced and objective content as well as robust and standardized processes for content delivery [94]. Its facilitation, implementation, and execution are through MA, either directly as company-led education, or indirectly via (educational) grants. Grant funding for medical education allows independence from commercial influence or control. Medical education must adhere to compliance and quality standards, providing value-enhancing medical knowledge and improving the quality use of medicines [95, 96].

Several industry codes include transparency reporting obligations such as fee-for-service and other transfers of value, e.g. travel support, for CME faculty or delegates, with some companies having additional stricter internal compliance regulations in place, which MA adheres to and proactively executes. Noteworthy, such declarations may not be binding for other types of educational providers [94].

2.3.3 Promotional Activities and External Engagement

While the commercial function is accountable for decision making for promotional activities and other commercially led activities (e.g., market research), MA is involved in governing processes that contribute to decisions over promotional activities (e.g., copy approval of promotional material) before execution. Industry codes and internal policies are established to guide the process with MA in a ‘gatekeeper’ position, ranging to personal legal liability in some jurisdictions for the approving person (e.g., Germany, Austria, France) and requiring medical or scientific qualification for the signatory [97].

MA interactions with external stakeholders are governed by company policies, ensuring high value on principles of accuracy, fair balance, and transparency. Noteworthy, MA personnel are not evaluated or compensated for sales goals and their role is non-promotional, with reporting and budgets structured separately to commercial functions. Together with their scientific and/or medical background, this enables MA to act in an ethic and patient-centric manner, being perceived as a credible and balanced source to exchange relevant medical information by KOLs, health care professionals, patient advocacy groups and other stakeholders [15, 65, 84].

3 Discussion

Global health is a key enabler for economic opportunity, however equitable access to health services remains challenging [98]. Innovative partnerships with the private sector are vital for improving public health [99]. Indeed, adding a health component (H) to ESG to create an ESG + health (H) framework has been recommended for incorporation into mainstream financial decision making and scalable investment [98]. Health industries, including pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and related life sciences, are often criticized for being centered around commercial agreements and overlooking ESG and sustainability initiatives and collaborations [100].

Investing in ESG is a profitable strategy that also increases the market value of pharmaceutical companies [4]. ESG is a growing consideration, especially for investors, with more than US$51 billion in new investor money contributed to ESG funds in 2021. The total investment accounted for one-quarter of funding into all stocks in the US [99]. ESG measures also matter to consumers, as shown by a 2020 survey by Price Waterhouse Coopers, where 62% of consumers consider companies more positively if they take on active, socially responsible health measures [101]. Hence, the pressure on pharmaceutical firms to respond to the challenges posed by ESG is increasing.

However, the resources for the prioritization of commercial and research and development objectives may hinder the development of ESG strategies [4]. For example, while diversity in clinical trials creates an opportunity to include remote/rural health centers and community hospitals [60], such clinical trial enrolment of diverse patients may be offset by the environmental impact and costs of remote study visits. Moreover, enrolling diverse study populations may increase the risk for a ‘non-positive’ result due to higher variability [102]. Despite such a risk, data can be leveraged through statistical analysis and inform new or additional studies designed to individualize treatment options as well, as enrolling diverse populations does not automatically equate to heterogeneity in outcomes as there could be multiple factors at play, such as unequal access to care [60]. Failure to achieve meaningful and appropriate representation compromises the generalizability and subgroup-specific information about drug response and measures of safety and efficacy and may result in miscalculations of response rates, and erroneous estimates of treatment efficacy, potentially exacerbating health disparities [103].

Furthermore, not all ESG initiatives, particularly relating to the environment (for example, defossilization of the chemicals used for pharmaceutical manufacturing, supply chain or packaging optimization to reduce carbon footprint) and partly to governance, are in scope for MA, and the decisions for several of these initiatives may be carried out without any direct involvement of MA functions.

While there remain ESG gaps in the pharmaceutical industry, with some clearly outside the remit of MA, these can be addressed to some extent indirectly via funding of activities. The issuance of bonds linked to ESG metrics, where bondholders could receive more interest if a company meets or exceed targets for expanding access to its medicines or responding to other global health challenges it has identified, is an encouraged and initial step already in implementation [104, 105].

Setting clear and broadly accepted standardized KPIs and metrics for our industry is another step to be taken. For the environment, this could be measuring and reporting CO2 emissions and setting targets for when a company is expected to be carbon neutral. In this regard, the authors on the recent study investigating industry congress travel of a mid-sized pharmaceutical company by assessing carbon emissions, including the scope 3 framework of the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, are commended for their independent reporting of results, which should be considered to explore governance for future carbon audits and to compare results within industry [22].

Although MA places patient centricity at the forefront of its activities, the lack of standardized frameworks targeting to advance patient centricity via areas of specific focus has been acknowledged [106]. Such standardization should be further explored to generate KPIs for measurability and comparability to feed into the social pillar of ESG.

The pharmaceutical industry has a responsibility not only limited to its shareholders but also to other stakeholders—patients, consumers, individuals, and society as a whole, including future generations [107]. The long-term interest of the industry to fulfill expectations on ESG should go hand in hand with the concept of a ‘social license to operate’ that recognizes the contributions and allows the industry to operate as profitable research-based businesses on a sustainable long-term basis [8]. As such, any ESG strategy should be aligned with a company’s overall vision and mission. Organizations can differentiate themselves by acting early to build ESG strategies that can enhance reputations with customers, employees, investors, and analysts. ESG has emerged as a critical driver to generate opportunity and differentiate for each individual enterprise, including our industry [43].

Moving forward, a key driver for all ESG activities will be the industry’s ability to ‘walk the talk’. Considering all ESG ongoing efforts, the ESG promises by our industry need to be one thing—credible; and credibility comes over time, by repeatedly demonstrating action over words. Certainly, there are functions within the industry suited to be entrusted on ESG and establish credibility and sustainability thereof.

4 Conclusion

The involvement of MA in potentially driving ESG initiatives within the pharmaceutical industry is a relatively nascent yet crucial area of exploration. The strategic integration of MA in ESG initiatives aligns with the function’s core imperatives of patient centricity, credibility, and adherence to compliance. As we navigate through an era marked by an increasing emphasis on ESG principles, the potential of the MA function for involvement and contribution in this space is not only significant but could also prove relevant for the sustainable future of the industry. Integration of MA in ESG strategies not only underpins the sustainable and ethical operations of the industry but could also bear far-reaching implications for patient health and public well-being.

In this manuscript, we chose some examples of key initiatives supporting ESG determinants for which MA could be a strategic leader. This is by no means an exhaustive list and it is not meant to be. The climate crisis and its global threats have inspired forward-thinking pharmaceutical companies to redefine the evolving role of MA. These innovative companies are positioning the MA function to do sustainable business and thereby create a competitive advantage in our opinion. Recent development has shown that HCPs prefer a scientific partner in the healthcare industry (as opposed to the traditional ‘customer and seller’ relationship), fostering a more collaborative approach. Shareholders have become increasingly conscientious and are seeking transparency about what companies are doing in ESG. Do biopharmaceutical companies have the ‘social license to operate’ and can they truly walk the talk? Further research is warranted to investigate this question.

References

Krishnamoorthy R. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing: Doing good to do well. Open J Soc Sci. 2021;9:189–97.

Chen CD, Su CJ, Chen MH. Are ESG-committed hotels financially resilient to the COVID-19 pandemic? An autoregressive jump intensity trend model. Tour Manag. 2022;93: 104581.

Jinga P. The increasing importance of environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing in combating climate change. 2021. In: Tiefenbacher JP (ed). Environmental management. ISBN 978-1-83962-547-3. IntechOpen. https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/77199.

López-Toro AA, Sánchez-Teba EM, Benítez-Márquez MD, et al. Influence of ESGC indicators on financial performance of listed pharmaceutical companies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4556.

Lee MT, Suh I. Understanding the effects of environment, social, and governance conduct on financial performance: arguments for a process and integrated modelling approach. Sustain Technol Entrepreneurship. 2022;1(1): 100004.

Governance and Accountability Institute Inc. (G&A). 2020 Flash Report Russell 1000®. Trends on the sustainability reporting practices of the Russell 1000 index companies. https://www.ga-institute.com/research-reports/flash-reports/2020-sp-500-%20flash-report.html. Accessed 30 Sep 2022.

McKinsey. Does ESG really matter—and why? 10 August 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/does-esg-really-matter-and-why. Accessed 6 May 2023.

Pharmaceutical Executive, June 2022, Vol 42, No 6. https://cdn.sanity.io/files/0vv8moc6/pharmexec/339f103f01e043f652e39f8c0e72f3795fb71f60.pdf/PharmaceuticalExecutive_June2022. Accessed 10 Jul 2022.

Romanello M, McGushin A, Di Napoli C, et al. The 2021 report of the Lancet countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. Lancet. 2021;398(10311):1619–62.

Marmot M, Allen J, Goldblatt P, et al. Build Back Fairer: the COVID-19 marmot review. 2020. The pandemic, socioeconomic and health inequalities in England. London: Institute of Health Equity. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2020/Build-back-fairer-the-COVID-19-Marmot-review.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Paschke A, Dimancesco D, Vian T, et al. Increasing transparency and accountability in national pharmaceutical systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96(11):782–91.

ESG-Healthcare: macroeconomic trends. Published 22 Feb 2022. https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/comment/esg-top-trends-in-healthcare-macroeconomic-trends/. Accessed 27 Jul 2022.

Booth A, Jager A, Faulkner SD, et al. Pharmaceutical company targets and strategies to address climate change: content analysis of public reports from 20 Pharmaceutical companies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):3206.

Aksoy L, Buoye AJ, Fors M, et al. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) metrics do not serve services customers: a missing link between sustainability metrics and customer perceptions of social innovation. J Serv Manag. 2022;33:565–77.

Setia S, Ryan NJ, Nair PS, et al. Evolving role of pharmaceutical physicians in medical evidence and education. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:777–90.

Furtner D, Shinde SP, Singh M, et al. Digital transformation in medical affairs sparked by the pandemic: insights and learnings from COVID-19 era and beyond. Pharmaceut Med. 2022;36(1):1–10.

Belkhir L, Elmeligi A. Carbon footprint of the global pharmaceutical industry and relative impact of its major players. J Clean Prod. 2019;214:185–94.

Mutascu M. CO2 emissions in the USA: new insights based on ANN approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(45):68332–56.

The White House. Executive order on tackling the climate crisis at home and abroad. Jan 27, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/27/executive-order-on-tackling-the-climate-crisis-at-home-and-abroad/. Accessed 2 May 2023.

Hill AC, Babin M. What the historic U.S. climate bill gets right and gets wrong. Aug 17, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/us-climate-bill-inflation-reduction-act-gets-right-wrong-emissions. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Sanguesa JA, Torres-Sanz V, Garrido P, et al. Review on electric vehicles: technologies and challenges. Smart Cities. 2021;4:372–404.

Gattrell WT, Barraux A, Comley S, et al. The carbon costs of in-person versus virtual medical conferences for the pharmaceutical industry: lessons from the coronavirus pandemic. Pharmaceut Med. 2022;36(2):131–42.

Philippe H. Less is more: decreasing the number of scientific conferences to promote economic degrowth. Trends Genet. 2008;24(6):265–7.

Ponette-González AG, Byrnes JE. Sustainable science? Reducing the carbon impact of scientific mega-meetings. Ethnobiol Lett. 2011;2:65–71.

Milford K, Rickard M, Chua M, et al. Medical conferences in the era of environmental conscientiousness and a global health crisis: the carbon footprint of presenter flights to pre-COVID pediatric urology conferences and a consideration of future options. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56(8):1312–6.

Leddin D, Galts C, McRobert E, et al. The carbon cost of travel to a medical conference: modelling the annual meeting of the Canadian association of gastroenterology. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2021;5(2):52–8.

Zotova O, Pétrin-Desrosiers C, Gopfert A, et al. Carbon-neutral medical conferences should be the norm. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(2):e48–50.

Tao Y, Steckel D, Klemeš JJ, et al. Trend towards virtual and hybrid conferences may be an effective climate change mitigation strategy. Nat Commun. 2021;12:7324.

Lynch J. Availability of disaggregated greenhouse gas emissions from beef cattle production: a systematic review. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2019;76:69–78.

Rust NA, Ridding L, Ward C, et al. How to transition to reduced-meat diets that benefit people and the planet. Sci Total Environ. 2020;718: 137208.

Kolbe K. Mitigating climate change through diet choice: costs and CO2 emissions of different cookery book-based dietary options in Germany. Adv Clim Change Res. 2020;11:392–400.

Filho WL, Setti AFF, Azeiteiro UM, et al. An overview of the interactions between food production and climate change. Sci Total Environ. 2022;838(Pt 3): 156438.

Parncutt R, Lindborg P, Meyer-Kahlen N, et al. The multi-hub academic conference: global, inclusive, culturally diverse, creative, sustainable. Front Res Metrics Anal. 2021;6:699–782.

Yates J, Kadiyala S, Li Y, et al. Can virtual events achieve co-benefits for climate, participation, and satisfaction? Comparative evidence from five international agriculture, nutrition and health academy week conferences. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6(2):e164–70.

Setia S, Tay JC, Chia YC, et al. Massive open online courses (MOOCs) for continuing medical education—why and how? Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:805–12.

Walsh K. E-learning in medical education: the potential environmental impact. Educ Prim Care. 2018;29(2):104–6.

Sustainable Trials Study Group. Towards sustainable clinical trials. BMJ. 2007;334(7595):671–3.

Roberts I, Yates D, CRASH Trial Collaborators, et al. Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10008 adults with clinically significant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9442):1321–8.

Greenhouse Gas Protocol. About WRI & WBCSD. https://ghgprotocol.org/about-wri-wbcsd. Accessed 2 Sep 2022.

Ravindrane R, Patel J. The environmental impacts of telemedicine in place of face-to-face patient care: a systematic review. Future Healthc J. 2022;9(1):28–33.

Beelke ME. The evolving role of medical affairs: opportunities for discovery, preclinical and clinical research. J Clin Stud. 2017;9(3):20–4.

Dănescu T, Popa MA. Public health and corporate social responsibility: exploratory study on pharmaceutical companies in an emerging market. Global Health. 2020;16(1):117.

Price Waterhouse Coopers. ESG for pharmaceutical and life sciences companies. Aug 2021. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/health-industries/library/assets/pwc-esg-health-insights-pls.pdf. Accessed 15 Jul 2022.

Price Waterhouse Coopers. ESG for healthcare organizations. Aug 2021. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/health-industries/library/assets/pwc-esg-health-insights-health-org.pdf. Accessed 15 Jul 2022.

Medical Affairs Professional Society. The future of medical affairs 2030. https://medicalaffairs.org/future-medical-affairs-2030/. Accessed 14 Jul 2022.

Phillips G, Elliott J. The path to patient centricity closing the ‘how’ gap. Aug 2018. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2018-09/ipsos-healthcare-the-path-to-patient-centricity-august-2018.pdf. Accessed 18 Jul 2022.

du Plessis D, Sake JK, Halling K, et al. Patient centricity and pharmaceutical companies: is it feasible? Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(4):460–7.

Ashkenazy R. Building the case for developing a medical affairs patient-centric framework collaboratively. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25(3):475–9.

Pile K, Norager R, Skillecorn M, et al. Elevating the role of carers in rheumatoid arthritis management in the Asia–Pacific region. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020;23(7):898–910.

Furtner D, Norager R, Yasuda M, et al. Treatment preferences, patient goals and shared decision making in moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis: exploring patient and rheumatologist perceptions. In: Poster #88 presented at the 22nd Asia Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR), virtual congress, 24–29 Oct 2020.

Sharma NS. Patient centric approach for clinical trials: current trend and new opportunities. Perspect Clin Res. 2015;6(3):134–8.

Crawford LS, Matczak GJ, Moore EM, et al. Patient-centered drug development and the learning health system. Learn Health Syst. 2017;1(3): e10027.

Timpe C, Stegemann S, Barrett A, et al. Challenges and opportunities to include patient-centric product design in industrial medicines development to improve therapeutic goals. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(10):2020–7.

Bergerot CD, Pal SK, Tripathi A. Patient-reported outcomes in early phase clinical trials: an opportunity to actively promote patient-centered care. Oncologist. 2022;27(9):714–5.

Nephew LD. Accountability in clinical trial diversity: the buck stops where? EClinicalMedicine. 2021;36: 100906.

FDA guidance for industry. Diversity plans to improve enrollment of participants from underrepresented racial and ethnic populations in clinical trials guidance for industry. Apr 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/157635/download. Accessed 4 Sep 2022.

Hines PA, Janssens R, Gonzalez-Quevedo R, et al. A future for regulatory science in the European Union: the European Medicines Agency’s strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(5):293–4.

European Medicines Agency. Patient experience data in EU medicines development and regulatory decision-making. 17 Oct 2022. EMA/354012/2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/executive-summary-patient-experience-data-eu-medicines-development-regulatory-decision-making_en.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2023.

Calvert MJ, Cruz Rivera S, Retzer A, et al. Patient reported outcome assessment must be inclusive and equitable. Nat Med. 2022;28(6):1120–4.

Chaudhry MS, Spahn J, Patel S, et al. Myths about diversity in clinical trials reduce return on investment for industry. Nat Med. 2022;28(8):1520–2.

Ciani O, Jommi C. The role of health technology assessment bodies in shaping drug development. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2014;8:2273–81.

Panteli D, Eckhardt H, Nolting A, et al. From market access to patient access: overview of evidence-based approaches for the reimbursement and pricing of pharmaceuticals in 36 European countries. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:39.

Olson MS. Developing an integrated strategy for evidence generation. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7(1):5–9.

Khosla S, White R, Medina J, et al. Real world evidence (RWE)—a disruptive innovation or the quiet evolution of medical evidence generation? F1000Res. 2018;7:111.

Sweiti H, Wiegand F, Bug C, et al. Physicians in the pharmaceutical industry: their roles, motivations, and perspectives. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24(9):1865–70.

Aliu P, Sarp S, Reichenbach R, et al. International country-level trends, factors, and disparities in compassionate use access to unlicensed products for patients with serious medical conditions. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(4): e220475.

Rabea M. Understanding the factors that impact the pre-launch phase and new product launch excellence in the pharmaceutical industry. AmJ Ind BusManag. 2022;12:88–122.

Price Waterhouse Coopers 2016. The early access to medicines scheme (EAMS)—an independent review. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/509612/eams-review.pdf. Accessed 7 Aug 2022.

Patil S. Early access programs: benefits, challenges, and key considerations for successful implementation. Perspect Clin Res. 2016;7(1):4–8.

Bates AK. Implementing a pre-launch named patient programme: evidence of increased market share. J Med Market. 2008;8(4):319–24.

Klonoff DC. The new FDA real-world evidence program to support development of drugs and biologics. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2020;14(2):345–9.

Rozenberg O, Greenbaum D. Making it count: extracting real world data from compassionate use and expanded access programs. Am J Bioeth. 2020;20(7):89–92.

Polak TB, Cucchi DGJ, van Rosmalen J, et al. Generating evidence from expanded access use of rare disease medicines: challenges and recommendations. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13: 913567.

Polak TB, Cucchi DGJ, van Rosmalen J, et al. Real-world data from expanded access programmes in health technology assessments: a review of NICE technology appraisals. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1): e052186.

Werling K, et al. Focus on fife science compliance: the evolution of medical affairs departments. AHLA Connections. Nov 2011. https://www.mcguirewoods.com/news-resources/publications/health_care/focus-life-science-compliance-nov-2011.pdf. Accessed 3 Sep 2022.

EFPIA. Working together for patients: grants and donations. https://www.efpia.eu/media/25671/working-together-for-patients-grants-and-donations.pdf. Accessed 3 Sep 2022.

Bero LA, Parker L. Risky business? Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship of health consumer groups. Aust Prescr. 2021;44(3):74–6.

Bristol Myers Squibb. 2021 environmental, social and governance report. https://www.bms.com/assets/bms/us/en-us/pdf/bmy-2021-esg-report.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2023.

Pfizer. 2022 environmental, social & governance report. https://www.pfizer.com/sites/default/files/investors/financial_reports/annual_reports/2022/files/Pfizer_ESG_Report.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2023.

AbbVie. 2022 ESG action report. https://www.abbvie.com/content/dam/abbvie-com2/pdfs/abbvie-esg-action-report.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2023.

Teva. 2021 environmental, social and governance progress report. https://www.teva.de/library/media/project/teva/company/about-teva/teva-esg-progress-report-2021.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2023.

Price Waterhouse Coopers. How health organizations can integrate ESG priorities? What’s right for the world is good for business. PWC. Published Aug 2021. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/health-industries/library/esg-health-industry.html. Accessed 28 Jul 2022.

Tettamanzi P, Venturini G, Murgolo M. Sustainability and financial accounting: a critical review on the ESG dynamics. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(11):16758–61.

Jacob NT. Drug promotion practices: a review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(8):1659–67.

Ravela R, Lyles A, Airaksinen M. National and transnational drug shortages: a quantitative descriptive study of public registers in Europe and the USA. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):940.

Gicic A, Li S, Amini S, et al. A cross-sectional investigation of the impact of COVID-19 on community pharmacy. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2022;6: 100145.

Lau B, Tadrous M, Chu C, et al. COVID-19 and the prevalence of drug shortages in Canada: a cross-sectional time-series analysis from April 2017 to April 2022. CMAJ. 2022;194(23):E801–6.

Kotecha P, Light A, Checcucci E, et al. Repurposing of drugs for COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Panminerva Med. 2022;64(1):96–114.

Li QY, Lv Y, An ZY, et al. Ethical review of off-label drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10(17):5541–50.

Hermsen ED, Sibbel RL, Holland S. The role of pharmaceutical companies in antimicrobial stewardship: a case study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(3):677–81.

Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, et al. Effectiveness of continuing medical education. Evidence report/technology assessment no. 149 (prepared by the Johns Hopkins Evidence-based Practice Center, under contract no. 290-02-0018). AHRQ publication no. 07-E006. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007.

Williams A, Rushton A, Lewis JJ, et al. Evaluation of the clinical effectiveness of a work-based mentoring programme to develop clinical reasoning on patient outcome: a stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7): e0220110.

Cervero RM, Gaines JK. The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: an updated synthesis of systematic reviews. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(2):131–8.

Allen T, Donde N, Hofstädter-Thalmann E, et al. Framework for industry engagement and quality principles for industry-provided medical education in Europe. J Eur CME. 2017;6(1):1348876.

Pandya K, et al. Medical affairs improves patient outcomes through external medical education. In: Elevate magazine, external education. MAPS 2022. https://medicalaffairs.org/medical-affairs-patient-outcomes-external-medical-education. Accessed 2 Sep 2022.

Medicines Australia. Code of conduct. Edition 19. https://www.medicinesaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/65/2020/11/20200108-PUB-Edition-19-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 16 Jul 2022

Piriou C, Manenc C. BlueReg Pharma Consulting. Whitepaper promotional material review 2021. Responsible persons for promotion of medicinal products in France, Germany, Spain, Italy & United Kingdom. https://blue-reg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/White-Paper-Focus-mars-2021-Prom-Mat-Reviex.pdf. Accessed 7 May 2023.

Krech R, Kickbusch I, Franz C, et al. Banking for health: the role of financial sector actors in investing in global health. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(Suppl 1): e000597.

Serafeim G, Rischbieth AM, Koh HK. Sustainability, business, and health. JAMA. 2020;324(2):147–8.

Pereno A, Eriksson D. A multi-stakeholder perspective on sustainable healthcare: from 2030 onwards. Futures. 2020;122: 102605.

Bulik BS. Pharma ESG efforts overwhelmingly skew social, while environment and governance come up short: study. Fierce Pharma. Published August 2021. https://www.fiercepharma.com/marketing/pharma-esg-efforts-overwhelmingly-skew-social-while-environment-and-governance-come-up. Accessed 28 Jul 2022

Sharma A, Palaniappan L. Improving diversity in medical research. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):74.

Kahn JM, Gray DM 2nd, Oliveri JM, et al. Strategies to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion in clinical trials. Cancer. 2022;128(2):216–21.

Pfizer. Pfizer completes $1.25 billion sustainability bond for social and environmental impact. Press release, Mar 27, 2020. https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-completes-125-billion-sustainability-bond-social-and. Accessed 15 Jul 2022

Novartis. Novartis reinforces commitment to patient access, pricing a EUR 1.85 billion sustainability-linked bond. Press release, Sep 16, 2020. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-reinforces-commitment-patient-access-pricing-eur-185-billion-sustainability-linked-bond. Accessed 15 Jul 2022

Amin D, Vandenbroucke P. Advancing patient-centricity in medical affairs: a survey of patients and patient organizations. Drug Discov Today. 2023;28(7):103604.

Leisinger KM. The corporate social responsibility of the pharmaceutical industry: idealism without illusion and realism without resignation. Bus Ethics Q. 2005;15(4):577–94.

Wollensack L, Budzinski K, Backmann J. Defossilization of pharmaceutical manufacturing. Curr Opin Green Sus Chem. 2022;33:100586.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Thanh Ngoc Nhat Nguyen, Department of Professional Practice at KPMG Singapore, and Dr Sajita Setia, owner and executive director of Transform Medical Communications Ltd, Wanganui, New Zealand, for their contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The research and the preparation of this manuscript received no fees, grants or sponsorship from any funding agency in the commercial, public, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

Daniel Furtner, Gabor Hutas, Bryan Jie Wen Tan, and Roland Meier report no conflicts of interest in this work. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent or reflect in any way the official policy or position of their current or previous employers.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors (DF, GH, BT, and RM) participated in the conception of the idea, design, and interpretation of the facts and data. All authors participated in manuscript writing and were engaged in revising it for scientific content and approval before its submission for publication. All authors have also read and approved the final version.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Furtner, D., Hutas, G., Tan, B.J.W. et al. Journey from an Enabler to a Strategic Leader: Integration of the Medical Affairs Function in ESG Initiatives and Values. Pharm Med 37, 405–416 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-023-00485-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-023-00485-9