Abstract

Background

Overweightness and obesity represent a high burden on well-being and society. Strength training has positive effects on body composition and metabolic health for people who are overweight or obese. The evidence for psychological effects of strength exercises is unclear.

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess the psychological effects of strength exercises for people who are overweight or obese.

Methods

Relevant literature was identified by use of the PubMed and PsycINFO databases. For each study, effect sizes and corresponding variance estimates were extracted or calculated for the main effects of strength exercises on psychological outcomes.

Results

Seventeen studies were included. There was almost no overlap among the various measures of psychological constructs. The constructs were ordered into eight broad categories. Meta-analytical techniques revealed substantial heterogeneity in effect sizes, and combined with the low number of effect size estimates for each outcome measure, this precluded meta-analysis. Organization of the data showed that the evidence base so far does not show convincing effects of strength training on psychological outcome measures. Some weak effects emerged on self-efficacy, self-esteem, inhibition, and psychological disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression). No additional or comparable effects to other interventions were found for mood, outcome expectations, quality of life, and stress.

Discussion

The main finding of this review is that despite a strong theoretical basis for expecting positive effects of strength training on psychological outcomes, the literature shows a large gap in this area. The existing research does not show a clear picture: some positive results might exist, but there is a strong need to accumulate more evidence before drawing conclusions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The literature on the effects of strength exercises on psychological outcomes is fragmented in terms of outcome measures and shows considerable heterogeneity. |

Synthesis of the outcomes shows weak effects of strength exercises on psychological outcomes. |

This incompleteness of the evidence base, in combination with the strong theoretical basis for assuming positive effects of strength exercises on psychological outcomes, implies an urgent need for more research. |

1 Introduction

Overweightness and obesity are worldwide problems with high costs to society and personal well-being [1, 2]. Being physically active can both prevent and decrease overweightness and obesity [3]. The substantial public health benefits of successfully promoting exercise in these populations has resulted in a multitude of behavior change interventions targeting exercise. However, meta-analyses showed that few such attempts yielded the desired results [4,5,6,7]. It was recently argued that these failures may be partly explained by the wrong choice of behavioral change [8, 9], i.e. many exercise interventions often promote aerobic exercises (see next paragraph). People who are overweight or obese differ from non-overweight people in that they have more weight to carry during exercises. In an absolute sense, this means that, in addition to a higher fat mass, they have higher muscle mass compared to the non-overweight people [10].

These biological differences have not yet been translated to the health psychology field. They could be of substantial benefit to intervention development efforts as health psychology theories make interesting predictions about these dynamics. For example, whereas people who are overweight or obese are unlikely to have mastery experiences when engaging in aerobic exercise, this is much more likely when they engage in strength exercise. Therefore, strength exercise will likely result in increased self-efficacy (e.g., Bandura [11] and Kelder et al. [12]). Self-efficacy is an important determinant of health behavior [13], including exercise behavior [14]. Similarly, when exercising together with non-overweight peers, the superior performance of people who are overweight on strength exercises can foster positive outcome expectations [9].

We previously proposed to combine these biological and psychological insights to argue in favor of exercises for people who are overweight or obese focusing on strength, suggesting that: (1) people who are overweight or obese are stronger (in the absolute sense) and better at (absolute) strength exercises compared with normal weight people; (2) strength exercises are easier for people who are overweight compared with aerobic exercises, and therefore compliance is greater; (3) people who are overweight may enjoy strength exercises, by being better at strength exercises than aerobic exercises than normal-weight people, facilitating long-term behavior change; (4) strength exercises have beneficial effects on the body composition of people who are overweight or obese and thus on metabolic and cardiovascular health [8, 9].

As a first step towards considering strength exercises in health behavior change interventions targeting overweightness and obesity, it is necessary to systematically map what is known about the differential psychological consequences of strength versus aerobic exercise. Indeed, strength training does have positive effects on body composition and health for people who are overweight or obese [15], but the evidence for positive psychological effects is limited (e.g., Lubans et al. [16]) and still unclear at present (for an extensive overview, see Lloyd et al. [17]) [18]. In an earlier review by Schranz and colleagues [19], the effects of strength training on strength, body composition, and psychosocial status were examined in adolescents who are overweight or obese. In their review, four papers that focused on psychological outcomes were included, but in none of these four studies was the independent effect of strength training on psychological outcomes reported (i.e., two studies compared a resistance + aerobic + diet intervention with a diet intervention; one study examined the effects of a combined resistance + aerobic + diet + behavioral therapy intervention vs. a no-intervention control group, and one study examined the time effects of a combined resistance + aerobic + behavioral therapy intervention). Additionally, the limited number of studies and conflicting findings prevented a definitive conclusion. The aim of the current systematic review was to assess the independent psychological effects of strength training or strength exercises for people who are overweight or obese.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Sources and Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Data Extraction

For the literature review, no restrictions were made regarding year of publication, language of the manuscript (although all manuscripts found were in English), or design of the study. Because of the expected limited number of studies in this specific area, three criteria were originally used for inclusion. Initially, we aimed to develop a search strategy to locate all studies in (1) people (all ages and both sexes) who are overweight or obese that reported the effect of (2) strength exercises on (3) at least one psychological construct. However, for the literature search, this last criterion turned out to be not feasible, because the psychological outcomes were too varied depending on the underlying theoretical concept. Given our aim of identifying any effects that strength exercises may have on psychological outcomes, it proved impossible to capture this last criterion in query terms without running a considerable risk of excluding potentially relevant literature. Therefore, we used the first two criteria and then selected papers that mentioned any psychological concepts, first based on title and abstract and later on full text (see Table 1). Only studies that reported the independent effect of strength training on psychological outcomes in overweight or obese people were included. No other restrictions were applied.

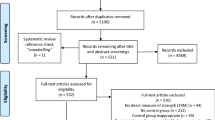

Relevant literature was identified using the PubMed and PsycINFO databases (first data search on 19 May 2014). In the first screening round (N = 7860) two screeners (GH and GK) identified 14 papers that met the eligibility criteria (see Fig. 1 for a flowchart showing the literature search progress). In a second and third screening round a total of three additional studies were found. The final number of included studies was 17. In the Supplementary Material at https://osf.io/8jbaz/ (Open Science Framework), a detailed list of all initial paper titles and abstracts can be found, including why papers were systematically excluded, together with the PRISMA checklist [20].

2.2 Study Quality and Categories

To acknowledge study quality and simultaneously take into account the intervention administered in the control group [21], we divided studies into five categories (see also Table 2). Studies in category I (a no-intervention control group compared to strength training) can answer the question of whether strength training has an effect on psychological outcomes. Studies in category II (an active control group vs. the same active control group plus strength training) can answer the question of whether strength training has added value over and above the active control group intervention. Studies in category III (an active control group vs. strength training) can answer the question of how strength training performs compared to the active control group intervention (e.g., diet or aerobic training). Category IV (an active control group (e.g., aerobic plus diet) versus strength training plus another active component (e.g., diet) can answer the question of how strength training performs compared to a given active component, when both are combined with another active component. Category V (studies lacking a control group, i.e., pretest–post-test designs) can provide very weak evidence for an effect of strength training over time, and was mainly included for the sake of completeness. To assess study quality, an additional risk of bias assessment was performed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool [22]; see also the Supplementary Material).

2.3 Measures of Psychological Outcomes

There was great variation in the psychological terminology used in the included studies. To establish which constructs could be aggregated, GtH extracted the variables and their operationalization from the included papers.

To determine which psychological outcome measures could be aggregated, two authors (GK and GJP) indicated which construct they thought was being measured. To establish this, they consulted the papers’ methodology sections where necessary. After this coding phase, two discussion rounds were conducted. In the first, both coders, facilitated by a third (GtH), discussed the terminology used where there were minor deviations [e.g., one author used “mood (inverted)” and the other “negative mood,” but the same variables were coded (90% consensus)]. In the second discussion round, more fundamental differences were discussed and resolved. After consensus was achieved, the psychological outcomes were ordered into eight broad categories: disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression), inhibition, mood, outcome expectations, quality of life, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and stress (see the Supplementary Material for the coding sheets). The resulting spreadsheet was then imported into R [23] for further analysis using metafor [24].

2.4 Analyses

For each study, effect sizes as well as corresponding variance estimates were extracted or calculated for the main effects of strength exercises on strength (as strength interventions are often focused on improvements in strength) and on psychological outcomes. Most studies used split-plot designs where within-subjects pre- and post-tests were combined with a between-subjects manipulation (see also Table 3). In such cases, computation of the effect sizes’ variance estimates requires the correlation between pre- and post-test measures [25], which was not reported by any of the papers. We therefore computed three types of variance estimates, assuming correlations of 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7 (corresponding to the qualitative labels for effect size as tentatively suggested by Cohen [26]). All analyses were therefore conducted three times. The results for the correlation estimate of 0.3 are reported, supplementing these reports with discussion of diverging outcomes where these occur.

Where studies reported multiple effect size estimates for variables that were coded as the same variable [e.g., “disinhibition” and “hunger” in Messier et al. [27] were both coded as “inhibition (inverted)”], these were first aggregated to obtain one estimate per variable per study. For these intra-study meta-analyses as well as the final between-study meta-analyses, random effects meta-analyses were conducted using the metafor package’s restricted maximum-likelihood estimator [24]. Heterogeneity was estimated using τ 2 (estimated between-study variance), I 2 (the proportion of variability in effect sizes due to heterogeneity rather than error), H 2 (total variability compared to sampling variability) and Q (the χ 2 test for heterogeneity), and forest and funnel plots were generated for each meta-analysis and are available in the Supplementary Material.

We identified “positive effects” of strength exercises in people who are overweight or obese as occurring when psychological constructs changed in the desired direction (e.g., increase in self-efficacy or decrease in psychological distress).

3 Results

3.1 Study Selection and General Characteristics

In total, 17 studies were included in the systematic review (Fig. 1). Based on our risk of bias assessment, the study quality of 13 papers was rated as “moderate” and four papers were rated as “weak” (see the Supplementary Material). Study characteristics are listed in Table 3. The number of participants in the different comparisons ranged from 32 [28] to 304 [29], with one extreme of 10,386 participants [30]. The intervention period ranged from an acute session of strength exercises [31] to 48 weeks’ training [32]. Seven studies included a comparison between strength training and a no-intervention control group (category I; see also Table 2 for examples). Eight studies included comparisons between an active control group (e.g., diet) and the same control group plus strength training (category II). Three studies compared strength training to aerobic training (i.e., an active control group—category III). One study compared strength training plus diet to aerobic training plus diet (category IV). Finally, three studies employed a pretest–post-test design (category V). Thirteen studies were in adults. All studies included a specific group of people who were overweight or obese (see Table 3).

3.2 Study Outcomes: Psychological Benefits

The 17 included studies had many different psychological outcomes. These are summarized in Table 4.

Based on the available data, for two studies [32, 34] no effect sizes could be calculated, and, therefore, these were not included in the meta-analysis. One additional study [36] was excluded for meta-analysis, as this study examined the acute effects of one strength exercise session. For all other studies effect sizes were calculated based on pre- and post-test means, standard deviations (SDs) and n values in both the strength-exercise group and the comparison group. In one study [35] effect sizes were available. Study outcomes were divided into the five major study types and eight major outcome categories. All individual effect sizes and forest and funnel plots can be found in the Supplemental Material. Note that although the literature contained reports of the effect of strength training on eight different psychological variables, few studies were available for each variable; and as the various studies provided data to answer different research questions, few studies were available for meta-analysis. This small number of studies for meta-analysis made heterogeneity hard to assess. Effect sizes seemed quite consistently heterogeneous for the exercises’ effects on strength (see Supplementary Material). Heterogeneity varied from 0–100%, with p values from <0.001 to 1 (see also the Supplemental Material).

The current state of the literature means that it is unclear how results from the meta-analyses should be interpreted. Therefore, the outcomes will be discussed qualitatively. We have, however, used the meta-analysis to generate diamond plots to aid interpretation of the current evidence base.

The diamond plots show that all effects are weak, but most of them are in a positive direction (i.e., strength training has a possible positive influence on psychological outcomes). Some weak effects emerged on self-efficacy, self-esteem, and psychological disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression), but only compared to a no-intervention control group [first diamond plot (category I)]. The second diamond plot (category II) shows that strength exercises have possible favourable additional effects on psychological disorders, self-esteem, and inhibition when combined with another active component, but that they are weak and have no additional effects on stress, self-efficacy, quality of life, or outcome expectations. In the third diamond plot, strength exercises were compared with other interventions [e.g., diet or aerobic exercises (category III)], showing that strength has possible positive effects on self-esteem but no stronger effects than diet or aerobic interventions on psychological disorders, quality of life, or mood. For the fourth study type [an active control group (e.g., aerobic plus diet) vs. strength training plus another active component (i.e., diet)], no data were available [32]. For the fifth study type (pre–post-test design without a control group), positive time-effects for strength training were found for perceived well-being [31], health and life satisfaction [30], and behavioral expectation, self-regulation, and perceived satisfaction [35]. The study examining the acute effects of strength exercises showed some positive effects on well-being, but the results were inconclusive [36]. Subclassification by age (i.e., under 18 years and over 18 years) showed no clear differences in results (see the Supplemental Material).

4 Discussion

Seventeen studies were included in this systematic review investigating the psychological effects of strength training in people who are overweight or obese. Strength training for people who are overweight or obese had small positive effects on various psychological outcomes when compared to a no-intervention control group, but these effects were often comparable to those of aerobic and diet interventions (Fig. 2).

The various studies included in this review reflect a combination of high heterogeneity and a low number of existing studies. This reflects the unfortunate state of the literature, and is the main reason why our conclusions, despite our use of meta-analysis to aid interpretation, are tentative.

The two common responses to this combination of heterogeneity and low number of studies are (1) to conduct separate analyses to eliminate heterogeneity per analysis and (2) to combine outcome measures or study methodologies to maintain the number of studies in each analysis. It is difficult to conduct these responses at the same time and they are not reconcilable with each other. We therefore decided to report our analyses as they are. There is no evidence or theory to guide us to an “objectively optimal” solution, and given the current state of the literature, it will take some time before such guidance becomes available. The other consideration is that conducting multiple analyses sharply increases the probability of encountering statistical artifacts (e.g., making type 1 errors). We used a meta-analysis to generate diamond plots to aid interpretation of the current evidence base. In addition, we have provided the dataset (i.e., the extracted data), analyses, and output. This will enable other researchers to separate/pool analyses as they see fit given their specific research interests.

Possible hypotheses for similar effects of strength exercises compared to other interventions on psychological constructs are (1) that the proportion of female participants in some studies was quite high, which might have impacted the results, (2) that for people who are overweight their main goal of participating in physical activity, dietary, or combined weight-loss interventions is generally to lose weight [43], and (3) that the strength exercise component in some studies was limited: for example, in the study by Davis et al. [28], participants were provided with strength exercise equipment and laminated exercise cards with descriptions of the strength training exercise that needed to be executed at home.

In strength-training interventions, it is expected that people gain in muscular mass (lean mass), and therefore may not lose much weight despite a reduction in adipose tissue. Most studies in this systematic review reported that body strength improved after strength training compared to a no-intervention or other-intervention group, while body weight or body composition often did not differ significantly between a strength intervention group and comparison group(s). A first possibility for future studies might be to investigate the influence of giving feedback on body composition during strength interventions. Gaining strength, and ultimately obtaining a healthier body composition, might lead to a higher resting metabolic rate, increased total energy expenditure, and a decreased chronic diseases risk [44]. Thus, when participants in a strength-training program become stronger, this should also lead to (long-term) positive changes in body composition and health. However, these positive effects are often not reflected in reported short-term psychological outcomes of strength training as compared to other interventions.

Given that strength exercises performed similarly to alternative interventions, we might conclude that strength exercises are a viable alternative or addition to diet and/or aerobic interventions, but more research is necessary. Pescud and colleagues [43] reported that feedback on body composition is useful as a “surrogate” for feedback on weight loss, which motivated participants to continue participating in strength-training exercises.

While body composition was reported in 10 out of 18 studies, none of these studies indicated that changes in body composition were given as feedback to the participants. As noted in the previous paragraph, giving feedback on body composition could be a form of positive reinforcement to engage in strength exercises. Also, the reported psychological outcomes were mostly clinical outcomes or markers of quality of life. None of the outcomes focused on self-determination, although self-determination concepts are very popular in motivation and intervention studies of exercise behavior [45]. As we noted in Sect. 1, people who are overweight or obese may discover in a strength exercise program that they are stronger than normal-weight people, which may result in their motivation for exercising to become relatively more intrinsic [8, 9]. Measuring self-determination concepts as psychological constructs might give additional information about the effects of exercise training to be considered alongside that obtained from current clinical and quality-of-life measures.

The strengths of this systematic review are the focus on the independent psychological effects of strength training for people who are overweight, the use of meta-analysis, and the contribution to the available evidence for positive self-reported psychological effects of strength training. The weaknesses of this study relate to the limited range of psychological outcomes and the great variation in psychological terminology used in the included studies.

5 Conclusions

This review affords three conclusions. The first is that, indeed, strength exercises have possible positive effects on a number of psychological outcome measures in populations of people who are overweight or obese. The second is that these effects seem comparable to and sometimes stronger than those of aerobic and diet interventions. The third and main conclusion is that due to a lack of data both conclusions are provisional. There is a need for more research, and given the positive effects that can be expected based on theory and the promising patterns that seem present in the presently synthesized empirical evidence, the need is urgent. Future studies should include the effect of giving feedback on improved strength and body composition as motivators for strength-training continuation, as well as measure additional psychological outcomes such as self-determination concepts.

References

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387:1377–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X.

Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378:804–14. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1.

Heath GW, Parra DC, Sarmiento OL, et al. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. Lancet. 2012;380:272–81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60816-2.

Guerra PH, Nobre MR, Silveira JA, et al. The effect of school-based physical activity interventions on body mass index: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin (Sao Paulo). 2013;68:1263–73. doi:10.6061/clinics/2013(09)14.

Guerra PH, Nobre MRC, da Silveira JAC, et al. School-based physical activity and nutritional education interventions on body mass index: a meta-analysis of randomized community trials—project PANE. Prev Med. 2014;61:81–9. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.005.

Harris KC, Kuramoto LK, Schulzer M, et al. Effect of school-based physical activity interventions on body mass index in children: a meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;180:719–26. doi:10.1503/cmaj.080966.

Metcalf B, Henley W, Wilkin T. Republished research: effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (EarlyBird 54). Br J Sport Med. 2013;47:226. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-e5888rep.

Ten Hoor GA, Plasqui G, Schols AM, et al. Combating adolescent obesity: an integrated physiological and psychological perspective. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17:521.

Ten Hoor GA, Plasqui G, Ruiter RA, et al. A new direction in psychology and health: resistance exercise training for obese children and adolescents. Psychol Health. 2016;3:1–8.

Westerterp KR, Donkers JHHLM, Fredrix EWHM, et al. Energy intake, physical activity and body weight: a simulation model. Br J Nutr. 1995;73:337–47. doi:10.1079/BJN19950037.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc; 1986.

Kelder S, Hoelscher D, Perry CL. How individuals, environments, and health behaviour interact: social cognitive theory. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior: theory, research, and practice. 5th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2015. p. 285–325.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2010.

Hagger MS, Chatzisarantis N, Biddle SJ. The influence of self-efficacy and past behaviour on the physical activity intentions of young people. J Sport Sci. 2001;19:711–25. doi:10.1080/02640410152475847.

Alberga AS, Farnesi BC, Lafleche A, et al. The effects of resistance exercise training on body composition and strength in obese prepubertal children. Phys Sportsmed. 2013;41:103–9. doi:10.3810/psm.2013.09.2028.

Lubans DR, Smith JJ, Morgan PJ, et al. Mediators of psychological well-being in adolescent boys. Adolesc Health. 2016;58(2):230–6. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.010.

Lloyd RS, Faigenbaum AD, Stone MH, et al. Position statement on youth resistance training: the 2014 international consensus. Br J Sports Med. 2013;. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092952 online first; 15/7/2013.

Schranz N, Tomkinson G, Parletta N, et al. Can resistance training change the strength, body composition and self-concept of overweight and obese adolescent males? A randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2014;. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092209.

Schranz N, Tomkinson G, Olds T. What is the effect of resistance training on the strength, body composition and psychosocial status of overweight and obese children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2013;43:893–907. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0062-9.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

De Bruin M, Viechtbauer W, Hospers HJ, et al. Standard care quality determines treatment outcomes in control groups of HAART-adherence intervention studies: implications for the interpretation and comparison of intervention effects. Health Psychol. 2009;28:668–74. doi:10.1037/a0015989.

Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, et al. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):12–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016. URL: https://www.R-project.org/.

Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. URL: http://www.jstatsoft.org/v36/i03/

Becker BJ. Synthesizing standardized mean-change measures. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1988;41:257–78. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8317.1988.tb00901.x.

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

Messier V, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Doucet E, et al. Effects of the addition of a resistance training programme to a caloric restriction weight loss intervention on psychosocial factors in overweight and obese post-menopausal women: a Montreal Ottawa New Emerging Team study. J Sport Sci. 2010;28:83–92. doi:10.1080/02640410903390105.

Davis KK. Effect of mindfulness meditation and home-based resistance exercise on weight loss, weight loss behaviors, and psychosocial correlates in overweight adults. ProQuest; 2008. University of Pittsburg (PhD Thesis). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/12208506.pdf?repositoryId=457.

Goldfield GS, Kenny GP, Alberga AS, et al. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on psychological health in adolescents with obesity: the HEARTY randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83:1123. doi:10.1037/ccp0000038.

Wicker P, Coates D, Breuer C. The effect of a four-week fitness program on satisfaction with health and life. Int J Public Health. 2015;60:41–7. doi:10.1007/s00038-014-0601-7.

Levinger I, Goodman C, Hare DL, et al. Psychological responses to acute resistance exercise in men and women who are obese. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:1548–52. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181a026e5.

Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Andersen RE, et al. Exercise in the treatment of obesity: effects of four interventions on body composition, resting energy expenditure, appetite, and mood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:269. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.65.2.269.

Fonzi LA. The effect of home-based resistance exercise in overweight and obese adults (Doctoral dissertation). University of Pittsburgh; 2005.

Ghroubi S, Elleuch H, Chikh T, et al. Physical training combined with dietary measures in the treatment of adult obesity a comparison of two protocols. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;52:394–413. doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2008.12.017.

Lau PW, Yu CW, Lee A, et al. The physiological and psychological effects of resistance training on Chinese obese adolescents. J Exerc Sci Fit. 2004;2:115–20.

Levinger I, Goodman C, Hare DL, et al. The effect of resistance training on functional capacity and quality of life in individuals with high and low numbers of metabolic risk factors. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2205–10. doi:10.2337/dc07-0841.

Levinger I, Selig S, Goodman C, et al. Resistance training improves depressive symptoms in individuals at high risk for type 2 diabetes. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:2328–33. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181f8fd4a.

Martins R, Coelho ESM, Pindus D, et al. Effects of strength and aerobic-based training on functional fitness, mood and the relationship between fatness and mood in older adults. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2011;51:489–96.

Plotnikoff RC, Eves N, Jung M, et al. Multicomponent, home-based resistance training for obese adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes. 2010;34:1733–41. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.109.

Sarsan A, Ardiç F, Özgen M, et al. The effects of aerobic and resistance exercises in obese women. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20:773–82. doi:10.1177/0269215506070795.

Williams DM, Dunsiger S, Davy BM, et al. Psychosocial mediators of a theory-based resistance training maintenance intervention for prediabetic adults. Psychol Health. 2016;31:1108–24. doi:10.1080/08870446.2016.1179740.

Yu CC, Sung RY, Hau KT, et al. The effect of diet and strength training on obese children’s physical self-concept. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2008;48:76–82.

Pescud M, Pettigrew S, McGuigan M, et al. Factors influencing overweight children’s commencement of and continuation in a resistance training program. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:709. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-709.

Dixon JB. The effect of obesity on health outcomes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:104–8. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2009.07.008.

Teixeira PJ, Carraça EV, Markland D, et al. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:78. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-78.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gill ten Hoor, Gjalt-Jorn Peters, and Gerjo Kok conceived of, designed, and coordinated the review. Gill ten Hoor and Tim Frissen conducted the first literature search. Gill ten Hoor, Gjalt-Jorn Peters, and Gerjo Kok performed the analyses and drafted the manuscript. Tim Frissen, Guy Plasqui, and Annemie Schols participated in the design and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw; project number 525001004).

Conflicts of Interest

Gill ten Hoor, Gerjo Kok, Gjalt-Jorn Peters, Tim Frissen, Annemie Schols, and Guy Plasqui declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this review.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

ten Hoor, G.A., Kok, G., Peters, GJ.Y. et al. The Psychological Effects of Strength Exercises in People who are Overweight or Obese: A Systematic Review. Sports Med 47, 2069–2081 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0748-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0748-5