Abstract

Background and Objectives

There are significant challenges when obtaining clinical and economic evidence for health technology assessments of rare diseases. Many of them have been highlighted in previous systematic reviews but they have not been summarised in a comprehensive manner. For all stakeholders working with rare diseases, it is important to be aware and understand these issues. The objective of this review is to identify the main challenges for the economic evaluation of orphan drugs in rare diseases.

Methods

An umbrella review of systematic reviews of economic studies concerned with orphan and ultra-orphan drugs was conducted. Studies that were not systematic reviews, or on advanced therapeutic medicinal products, personalised medicines or other interventions that were not considered orphan drugs were excluded. The database searches included publications from 2010 to 2023, and were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane library using filters for systematic reviews, and economic evaluations and models. These filters were combined with search terms for rare diseases and orphan drugs. A hand search supplemented the literature searches. The findings were reported by a compliant Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Results

Two hundred and eighty-two records were identified from the literature searches, of which 64 were duplicates, whereas five reviews were identified from the hand search. A total of 36 reviews were included after screening against inclusion/exclusion criteria, 35 from literature searches and one from hand searching. Of those studies 1, 27 and 8 were low, moderate and high quality, respectively. The reviews highlight the scarcity of evidence for health economic parameters, for example, clinical effectiveness, costs, quality of life and the natural history of disease. Health economic evaluations such as cost-effectiveness and budget-impact analyses were scarce, and generally low-to-moderate quality. The causes were limited health economic parameters, together with publications bias, especially for cost-effectiveness analyses.

Conclusions

The results highlighted issues around a considerable paucity of evidence for economic evaluations and few cost-effectiveness analyses, supporting the notion that a paucity of evidence makes economic evaluations of rare diseases more challenging compared with more prevalent diseases. Furthermore, we provide recommendations for more sustainable approaches in economic evaluations of rare diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This umbrella review provides a comprehensive overview of current issues for economic evaluations of orphan drugs in rare diseases. |

For economic evaluations of rare diseases, there is a paucity of evidence and a pronounced publication bias, as a result, few cost-effectiveness analyses exist for orphan drugs. |

Stakeholders working with rare diseases can improve their work by following recommendations outlined in this umbrella review, for example, using comprehensive and flexible cost-effectiveness models. |

1 Background

The term orphan drug is recommended by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research when a drug is indicated for the treatment of rare diseases with a prevalence threshold of 40–50 patients per 100,000 people [2]. The US Orphan Drug Act of 1983 and the European Orphan Regulation (No. 141/2000) have provided drug manufacturers with research incentives for rare diseases [3, 4]. They are widely regarded as successful and have led to an increase in orphan-drug designations [5,6,7]. For example, in the USA, the number of orphan designations more than quadrupled from the 1990s to 2010s [8].

Before the introduction of incentives, there was a widely held view that manufacturers should be rewarded for orphan-drug development, which in exchange, meant that they could claim prices that ensured profitability. Although drug prices were high, the impact on healthcare budgets was negligible because of few marketed orphan drugs, and patients to benefit from them [9]. The situation has now changed because of the policy-induced surge in orphan drugs, and both policymakers and researchers are attempting to find sustainable solutions to the issue of reimbursement [9, 10].

The fundamental aim of clinical trials is regulatory approval, which involves a risk-benefit evaluation that should answer whether the benefit of an intervention outweighs the risk [11]. It is difficult to obtain high-quality trial data when investigating rare diseases. For example, it may be hard to recruit enough trial participants, hard endpoints may be missing and including placebo arms in clinical trials may be unethical [12, 13]. However, these challenges are often magnified when it comes to health technology assessments (HTAs), where the aim is a systematic assessment of both clinical and cost effectiveness [14]. These challenges lead to high uncertainty for cost-effectiveness analyses and along with their high prices result in many orphan drugs not being recommended for reimbursement [12, 13].

Multiple authors have described economic evaluation challenges for rare diseases, focusing on various aspects such as the decision analytic modelling component of economic evaluations. Some of the most influential papers, based on a number of citations, are from 2018 [9, 12, 13]. However, the literature is diverse, with researchers and policymakers looking for ways to alleviate the challenges for economic evaluations of orphan drugs [15, 16]. Recent events include the introduction of the Innovative Medicines Fund in the UK that facilitates the collection of additional data for promising orphan drugs or a living HTA, which is the concept of continuous updating of economic models [17, 18]. The existing reviews are limited in terms of their ability to synthesise the most recent policy, economic and clinical developments because they have been superseded by recent developments. Consequently, the issues, challenges and opportunities associated with the economic evaluation of orphan drugs have not been summarised comprehensively. As a result, an umbrella review that focuses on the challenges for economic evaluations of rare diseases is warranted.

2 Methods

Scoping searches helped inform the literature searches [1]. They confirmed that the surge in orphan drugs had resulted in a growing and disparate field of literature. Ultimately, the decision to conduct an umbrella review was made, which in this case, was deemed as an appropriate solution. Umbrella reviews aim to synthesise systematic reviews, with or without meta-analyses, and have been described as a natural option to handle increases in systematic reviews to provide a summary of broad topic areas [19]. Previously, this approach proved useful in similar situations, where fields of research expanded rapidly, and consequently, resulted in a diffuse body of literature [20,21,22].

2.1 Research Objectives

This research was informed by a modified version of the Setting, Perspective, Interest, Comparison, Evaluation (SPICE) framework [23]. The perspective component was omitted because all perspectives were considered relevant. When applying the framework with its parameters in brackets, for example, [Setting]. The research question became: in health-economic-research settings [Setting] are there any issues and challenges [Evaluation] for the economic evaluation of orphan drugs in rare diseases [Interest], which apply less to other drugs [Comparison]?

2.2 Literature Searches

The most relevant databases for the umbrella review were MEDLINE, Cochrane and EMBASE. Thus, during January 2023, MEDLINE and EMBASE were accessed through the Ovid platform and Cochrane independently through its website. For both MEDLINE and EMBASE, search filters for economic evaluations and models, and systematic reviews were sourced from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network databases, respectively [24,25,26]. These filters were combined with search terms for orphan drugs and rare diseases. Eligibility criteria, scoping and literature searches are available from the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM).

As recommended by Booth and colleagues, a hand search of references and bibliographies of papers from the review was conducted [27]. This was followed by a verification process where it was checked if any known and relevant papers were missing from the review.

2.3 Data Collection Process

Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent researchers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached. The papers that met the inclusion criteria, after screening of the title and abstract, were further subjected to full screening. Papers were also excluded at full screening if they were deemed as containing insufficient information to allow for meaningful data collection, for example, abstracts. The data collection process was divided into three steps: summary of characteristics, critical appraisal and data extraction.

2.3.1 Summary of Characteristics

An extraction table captured summary characteristics recommended for umbrella reviews: citations details, type of review, objectives, date range of database searching, number of studies, rating by the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist and themes [19].

2.3.2 Critical Appraisal

For the critical appraisal, the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist was used. This checklist is recommended by the umbrella review methodology working group for a critical appraisal of systematic reviews [19]. The checklist contains 11 questions that were used to critically appraise the reviews [28]. For this tool, there is high degree of freedom for deciding on a scoring system for the inclusion or exclusion of papers. To avoid missing any information, it was decided not to exclude any papers based on their scores. The reviews were divided into three levels according to their quality scores: 8–11 (high quality), 4–7 (moderate quality) and 0–3 (low quality) [29, 30].

2.3.3 Data Extraction

The included reviews were carefully assessed with the aim of identifying broader themes that pertain to economic evaluations of orphan drugs. Challenges were extracted and tabulated according to their themes, based on an approach previously used to extract modelling challenges for rare diseases [12].

3 Results

3.1 Literature Search and Study Selection

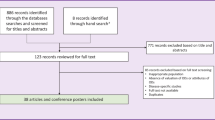

The study selection is illustrated by a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram in Fig. 1. The number of identified records was 282. They were retrieved from the following databases: EMBASE (n = 211), MEDLINE (n = 67) and Cochrane Library (n = 4). A total of 64 duplicate records were removed. Moreover, 172 records were excluded during screening of the abstract and title, which left 46 studies for full screening. Of those, 11 were excluded because of not containing components for economic evaluations (n = 5) or systematic reviews (n = 4), or because they were abstracts (n = 2). Overall, 35 reviews from the database searches were deemed eligible for inclusion as listed in the ESM under literature search results.

The hand search yielded five papers, of which four were excluded for the following reasons: no component of economic evaluations (n = 1) or systematic reviews (n = 2), and for not being concerned with orphan drugs (n = 1). It meant that one paper was carried forward from the hand search, which brought the total number of eligible reviews to 36. The ESM lists papers included for full screening.

3.2 Study Characteristics

A two-step approach was used to determine if studies could qualify as systematic reviews. First, a Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network search filter for systematic reviews was used, which is a pre-tested search strategy that identifies the higher quality evidence from vast amounts of literature indexed in a medical database. Second, eligibility was assessed, and a consensus obtained between the first and second reviewer on their inclusion. Using this approach, two scoping reviews were included because the methods were sufficiently systematic [31, 32]. Similarly, a study described their approach as a series of targeted literature reviews, which was also sufficiently systematic for inclusion [12]. The number of records included in the systematic reviews varied between 2 and 338. The ESM provides a summary of study characteristics.

3.3 Critical Appraisal

One study had low quality [31]. The highest frequency was found in the category of moderate quality, which comprised 27 studies [12, 32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57], whereas eight studies were rated as having high quality [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. The ESM includes scores for each individual Joanna Briggs Institute checklist question across all studies, which showed that most studies (n = 35) obtained points from question 4, which was: Were the sources and resources used to search for studies adequate? Question 8 was not widely applicable and was fulfilled by the least studies (n = 4). Question 8 was: Were the methods used to combine studies appropriate? Critical appraisal methods used in individual systematic reviews were assessed by question 5: Were the criteria for appraising studies appropriate? Fourteen studies included appropriate criteria for critical appraisal, whereas in 13 studies it was unclear whether they did, seven studies did not, and for two studies the question was not applicable.

3.4 Data Extraction

The systematic reviews were divided into two categories: those that considered a specific rare disease (13 studies) and those that considered multiple rare diseases (23 studies). As shown in Fig. 2, three broad themes were identified: issues with health economic parameters, issues with health economic evaluations and issues with estimating value/reimbursement, with subtopics further developed for each theme. For issues with health economic parameters, the subtopics were the natural history of disease, clinical effectiveness, costs and quality of life. For issues with health economic evaluations, the subtopics were cost effectiveness and budget impact. For issues with estimating value or reimbursement, the subtopics were thresholds, value frameworks and multiple criteria decision analyses (MCDA). A repository of all extracted data on issues for economic evaluations of rare diseases is available in the ESM.

3.5 Issues with Health Economic Parameters

3.5.1 Natural History of Disease

Rare diseases often progress slowly or are chronic by nature, which make clinical trials insufficient as they tend to have short durations [12, 62]. The non-existence or limited number of studies that include data on prevalence and incidence further magnify issues [44, 48, 51]. Moreover, clinical experts are few and private practitioners may only encounter few rare disease cases, which make them difficult to diagnose, and expert advice on rare diseases might not be easy to find [12, 44, 45, 57]. Delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis make it difficult to define treatment-eligible cohorts [45, 50, 51, 58].

To summarise, an economic evaluation is challenging, for example for long-term modelling, because of missing data on the natural history of the disease or unknown rare disease trajectories [40]. Although registries can alleviate data issues, they may suffer from challenges such as diverging disease and diagnostic codes, data ownership and missing comparator data [12, 48, 50].

3.5.2 Clinical Effectiveness

Whilst clinical trials are common sources for effectiveness data in economic evaluations, appropriate clinical evidence is not always available for this purpose [57, 58]. Moreover, clinical trials may suffer from short durations, small sample sizes, premature termination, inadequate power, missing data or missing control arms, for example, for ethical reasons [12, 37, 45, 47, 57]. In addition, published long-term studies providing post-marketing data on safety and efficacy are rarely available [37, 38].

Other challenges are missing treatment guidelines, data to predict treatment responses, concerns on the patient relevance and the use of surrogate endpoints [40, 50, 52, 60, 63]. Comparator data are essential for economic evaluations, but might be missing for rare diseases, and if they are available, there might not be a consensus on the use of treatment regimes or treatment eligibility of patients, which result in heterogeneity across studies [39, 48, 50, 51]. A review found that studies reporting clinical evidence for orphan drugs had low-to-moderate quality, and none of them had high quality [60].

3.5.3 Costs

Cost-of-illness or burden-of-disease studies are scarce in rare diseases [12, 34, 39, 42, 43, 48, 52, 55]. Of those studies available, most are retrospective and only a small proportion of studies report indirect, non-medical or informal-care costs. [12, 34, 51, 58, 59]. Aggregated primary data are rarely available, hence, studies tend to report patient-reported claims or registry data [42].

It is complicated to transfer cost-of-illness results between different rare disease settings because of differences in study designs, methods and results. For example, one study estimated lost productivity without following recommendations for handling uncertainty [42]. A multitude of factors influence transferability such as data sources, geographical perspective, nomenclature, assumptions, discount rates, unit costs, treatment guidelines and value frameworks [34, 43, 46, 50].

3.5.4 Quality of Life

Quality-of-life studies in rare diseases are limited, but availability depends on the rare disease of interest [35, 39, 47]. For example, a review found two studies that included utility values for Cushing’s syndrome, whereas another review concerned with Crigler–Najjar syndrome found no data on the humanistic burden, apart from anecdotes on treatment challenges [39, 47]. In addition, there are data limitations on the quality of life of caregivers [63]. A probable explanation for the scarcity is the limited applicability of quantitative methods such as choice experiments or conjoint analysis in rare diseases, for example because of small sample sizes [35]. Furthermore, studies tend to be small, not randomised or controlled, which decreases the reliability of conclusions [51]. This scarcity of evidence may lead to the use of assumptions, for example, assumption of equal utility values across treatment arms or a linearity assumption of utilities between different timepoints [46, 47]. Moreover, the reviews highlight shortcomings in methods and reporting, for example, the failure to include utility values or mapping algorithms, and insufficiently describing the elicitation of utility weights [58, 64].

3.6 Issues with Health Economic Evaluations

3.6.1 Cost Effectiveness

Health economic evaluations for rare diseases are scarce. For example, a systematic review failed to identify any studies, whereas another noted a remarkable absence of pharmacoeconomic evidence [45, 58]. A notable opinion on the cause of scarcity is that limited information on input parameters simply deter people from attempting to construct cost-effectiveness analyses because it is presumed unachievable [62]. In brief, causes are missing patient-level data, high drug costs and the inability to measure effects for clinical or quality-of-life outcomes [55, 57, 62].

The difficulties for economic evaluations are driving factors for the use of assumptions to overcome challenges for cost-effectiveness modelling. For example, assumptions on mortality, efficacy, treatment and complications [55]. It is commonplace to use modelling techniques such as mapping algorithms or long-term extrapolation for outcomes because of data limitations [38, 47]. Moreover, limited patient numbers coupled with unreliable estimates of effects, symptoms and complications suggest that methods such as patient-level simulation modelling may have limited applicability in rare diseases [62].

Additionally, publication bias in relation to positive results or industry-sponsorship bias seems to be prominent in rare diseases [66, 67]. It may occur when manufacturers decide to publish only if they have favourable cost-effectiveness results, a post-marketing obligation, or an opportunity to adopt favourable input parameters and an advantageous interpretation of results [45, 62, 65]. Numerous reviews suggest issues of publication bias [38, 45, 49, 61, 65]. For example, Schuller et al. indicated a higher frequency of analyses in countries with post-marketing obligations [62]. Others found that studies failed to discuss the direction and magnitude of bias, despite using data from potentially biased sources [38, 61, 65]. Another review highlighted selection bias to explain conflicting cost-effectiveness results for a particular drug [49]. Additionally, it was highlighted that most studies were industry funded in a systematic review of cost-utility analyses for haemophilia [64]. Furthermore, incremental cost-utility ratios were significantly lower when published by industry compared with foundations and academia [49].

Most economic evaluations have moderate quality, and the failure to reach high quality may be partly attributed to a lack of good-quality model inputs (e.g. utility values that do not account for patient characteristics and disease severity) or because they omit lifetime horizons for chronic rare diseases [55, 59, 61]. Moreover, problems with reporting are frequently highlighted as another factor that may contribute to insufficient quality. For example, not adequately reporting discount rates, sensitivity analyses, utility weights, patient characteristics, funding sources and time horizons [38, 59, 64].

Transferability is another issue for cost-effectiveness results [57]. Cost-effectiveness analyses are heterogenous because of modelling variations in treatments, patient populations, time horizons, countries, cost-effectiveness thresholds, settings, year of analysis, comparators and assumptions [49, 51, 55, 59, 61, 62, 64]. Thus, a high degree of carefulness is advised when assessing the transferability of results across different healthcare settings [61].

3.6.2 Budget Impact

Studies on budget impact modelling are few, mostly from high-income or native English-speaking countries. If Kanters and colleagues’ suggestion is accurate, it is not possible to rule out publication bias as a cause for the scarcity of studies on budget-impact modelling [45]. Furthermore, they are low quality and show poor adherence to guidelines [33, 45]. A proportion of budget-impact studies fail to report side effects, drug-related services, life-extension costs, savings from mortality reductions and validation methods [33, 53]. The importance of assumptions should not be overlooked, which are frequently incorporated for target populations, population sizes, interventions, comparators, costs and market uptake [33].

3.7 Issues with Estimating Value and Reimbursement

3.7.1 Value Frameworks and Thresholds

Most countries require budget-impact and cost-effectiveness models as part of HTAs, but the appraisal process (e.g. cost-effectiveness thresholds) may vary across countries, thus making comparisons difficult. As mentioned, whilst evidence may be scarce, input parameters on prevalence, incidence, number of treatment-eligible patients, and clinical benefits are nonetheless needed when estimating the budget impact and cost effectiveness for rare diseases [54]. For Europe, reference pricing further adds to the complexity and may prevent launches of orphan drugs in low-income countries [57]. Overall, value frameworks may suffer from transparency and consistency issues. This largely makes budget-impact and cost-effectiveness analyses country specific [36, 61].

3.7.2 Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis

A multiple criteria decision analysis (MCDA) is an emerging value framework for orphan drugs because it offers an opportunity to include a broad range of value criteria, for example, societal, disease or treatment criteria [31, 41]. Critics highlight variations in scoring functions for value criteria as a significant limitation and for decision making it is difficult to observe consistent recommendations [41, 56]. Interestingly, by meticulous examination of value criteria weights and scores in MCDAs, Friedmann and colleagues suggested that traditional value aspects used in HTAs (budget impact and cost effectiveness) were considered unimportant by stakeholders involved in orphan drug appraisal processes. The most cited value criterion was disease severity (n = 10), cost effectiveness (n = 7) and budget impact (n = 3) were cited ten times, collectively [41]. By contrast, Mohammadshahi and colleagues found in their review an equal citation frequency for the value criteria: disease severity (n = 8), cost effectiveness (n = 8) and budget effect (n = 8) [32].

4 Discussion

This section discusses the umbrella review findings, which indicated multiple issues for the economic evaluation of orphan drugs in rare diseases. However, it was not possible, with confidence, to assert whether all issues for orphan drugs applied less to other drugs, which was part of the original research objective [1]. Many papers focused on the evidence for a specific disease or multiple diseases, rather than how it compares to other drugs. For example, a systematic review of available evidence on 11 high-priced inpatient orphan drugs found that study populations were significantly smaller in randomised trials for orphan drugs as compared with non-orphan drugs [45]. Other systematic reviews in rare diseases confirmed that study populations were small but did not compare to other drugs [12, 37, 57]. The magnitude of issues varies, and this is the case for orphan drugs and other drugs. Thus, some of these issues may also be applicable to other drugs; however, these issues are critical in the case of orphan drugs as the issues tend to be amplified. In acknowledgement of this inability to consistently compare to other drugs, the ESM provides an indication of commonality for issues with economic evaluations of orphan drugs.

4.1 Issues with Health Economic Parameters

Scarcity of evidence was reported for natural history of the disease, clinical effectiveness, costs and quality of life [12, 34, 39, 42,43,44,45, 47, 48, 51, 52, 55, 57, 58]. It was previously pointed out that there were simply no easy answers to the problem of assessing evidence for orphan drugs [9]. In this review, this was exemplified by analysts who expressed a hope, rather than an actionable plan, for better availability of clinical trials with longer time horizons to conduct a thorough analysis of cost effectiveness, for example, for paediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension [37]. Others have suggested that high drug prices and the inability to measure effects would discourage people from even attempting to construct cost-effectiveness analyses [62]. This interpretation contrasts with that of Picavet and colleagues who conclude that orphan drugs can meet traditional cost-effectiveness thresholds [49]. It is an option to use expert opinion if few data are available, although it may be difficult to obtain [68, 69].

Some strategies may help improve evidence sources, but most do require extensive resources. For example, registries have the potential to inform modelling on the natural history of disease or can help construct a replacement for the standard of care, which may be relevant for trials without a control arm [12, 62, 63]. In addition, surrogate markers can play a vital role when clinical trials have short durations, they may, however, be difficult to validate without long-term data [57]. Analysts have drawn attention to this matter and highlighted the importance of consulting experts and to source data from other similar diseases to fill data gaps, for example, quality of life associated with wheelchair confinement between multiple sclerosis (more prevalent) and Duchenne’s disease (less prevalent) [12]. Last, authors suggest investigating the geographical variation in treatment patterns, reporting of side effects, long-term trials in disease areas with little evidence and a Cochrane review group dedicated to systematic reviews that reduce evidence gaps for orphan drugs [37, 48, 60].

For cost-of-illness studies in rare diseases, first, the studies should be clear on their perspective; second, they should report indirect costs separately from direct costs, for example, lost productivity; third, they should report costs associated with prevented comorbidities; and fourth, they should provide clarity on applied discount rates [34, 42, 59, 63]. The importance of future research for informal care, in terms of costs and quality of life, was highlighted by multiple authors because rare diseases may have severe implications for the closest providers of care, for example, family and friends [34, 55, 63].

4.2 Issues with Health Economic Evaluations

Systematic reviews reported a scarcity of cost-effectiveness modelling studies [45, 58]. As alluded to earlier, it could suggest a strong link between evidence issues, publication bias and the observed paucity of cost-effectiveness analyses [62]. Researchers want economic evaluations with higher quality and extended time horizons [61]. To achieve this aim, without conducting a clinical trial, one could evaluate: entry-level agreements and registries for data collection, patient surveys to assess the burden of disease, Delphi techniques for validation, expert opinion for estimation, population-adjusted indirect comparisons to account for patient characteristics and rare events with high costs [12, 64].

The explanations for the paucity of budget-impact models may be in terms of input parameters, for example, issues around a lack of data for prevalence or incidence estimation could contribute to their paucity [48, 51]. Budget-impact models were low quality and rarely validated. Summarising recommendations for improvement, they simply were that researchers should adhere to guidelines [33, 70]. Furthermore, publication bias for budget-impact models cannot not be ruled out [45, 54]. Health technology assessment bodies often require them, but for manufacturers, being the cause of increased healthcare costs might not be a message worth communicating, thus providing an explanation for potential publication bias. It is plausible that the budget impact is less of a concern for rare diseases because a low prevalence can translate to a lower impact on budgets for payers, thus providing another explanation for the scarcity of publications.

4.3 Issues with Estimating Value and Reimbursement

The appropriateness of value frameworks in the context of rare diseases is debated. For traditional value frameworks, examples of proposed solutions are: weighting of quality-adjusted life-years according to disease severity and prevalence, categorising quality-adjusted life-years based on disease states, implementing higher cost-effectiveness thresholds and special rules for those that exceed thresholds, for example, managed entry-level agreements and stopping rules for cost containment [12, 57]. The UK is an example where some of these measures have been incorporated through the Innovative Medicines Fund for medicines that are promising but associated with high uncertainty or decision modifiers through highly specialised technology appraisals [17, 71].

As highlighted throughout this review, criticism of traditional value frameworks has partly been related to their limited transparency and transferability of results. Critics have suggested policymakers explore other frameworks, for example, MCDA. So far, this method has only seen sporadic implementation, but it is clearly emerging [31, 41]. The benefit of MCDA is the ability to include a range of value criteria, for example, the burden on caregivers [36, 41]. However, like traditional frameworks, transferability and transparency for MCDA are areas that warrant further research [41, 56]. However, it should be noted that using a different value framework will not solve the problem of evidence scarcity.

5 Recommendations

Challenges are abundant and solutions are not plentiful and rarely forthcoming. Stakeholders, however, must recognise that certain types of research are costly, and demanding these could further eliminate company incentives to research rare diseases [57]. For example, clinical trials with extended time horizons. Thus, there is a need for recommendations that are more sustainable. As a first step towards these, we provide practical recommendations that may help alleviate challenges identified in this umbrella review.

5.1 Comprehensive and Flexible Cost-Effectiveness Models

Data availability is critical at the time of economic evaluations for rare diseases, this is why economic models should be transparent, and uncertainty rigorously explored through sensitivity analyses and set up for continuous updating as data become available over time [59]. Continuous updating of cost-effectiveness models with new data is an unexplored opportunity, especially considering the necessity of post-launch monitoring or real-world data [12, 60]. Such a framework has been referred to as a living HTA [18, 72].

Furthermore, transparency may increase for other stakeholders who are not trained researchers because user-friendly interfaces, for example, Shiny apps in the software R, allow them to “safely” explore model scenarios without having to face backend code [73]. For risk-sharing agreements, rather than focussing purely on clinical endpoints, for example, survival, they could potentially allow for fully updated cost-effectiveness models.

Consequently, for economic evaluations of rare diseases, there is untapped potential for using living HTAs. What is more, it has been recommended to use cost-effectiveness models in rare diseases to facilitate an expected value of information analysis using inputs from, for example, phase II or registry data [12]. It provides researchers with an opportunity to address the root causes of uncertainty by reprioritising or initiating data collection efforts, for example, before initiation of a phase III trial or an HTA [74].

In summary, we recommend using comprehensive and flexible cost-effectiveness models, which report value of information as initially suggested by Pearson and colleagues, which should as a minimum include both expected value of perfect information and expected value of perfect parameter information [12].

5.2 Publication Bias and Ability to Meet Cost-Effectiveness Thresholds

In the case of bias, one unanticipated finding was the extent to which publication bias seemed to be an issue [38, 45, 61, 62, 65]. Unfortunately, failure to account for bias can result in overambitious claims, for example, that cost-effectiveness analyses for rare diseases can indeed meet traditional cost-effectiveness thresholds. In this example, most studies were industry funded, which made the authors speculate and wary of a potential publication bias [49]. Their sample of studies was not fully representative for economic evaluations of rare diseases because they mainly came from the literature, and if the hypothesis of publication bias is correct, there must be a higher likelihood that these studies were published, simply because they showed that cost-effective thresholds were reached.

Unfortunately, biased conclusions may disrupt ongoing efforts to improve reimbursement conditions for orphan drugs, and the momentum could be lost if policymakers take their conclusion at face value. The overall conclusion that cost-effectiveness analyses can meet common cost-effectiveness thresholds seems strongly contested by the findings of this review. In this example, the research would have been more convincing if the authors had considered cost-effectiveness analyses submitted to HTA bodies as compared to those available in the literature. We recommend further research to determine the effect of publication bias on the ability to meet cost-effectiveness thresholds and caution when interpreting results.

5.3 Other Opportunities

Researchers need to identify data gap years before economic evaluations to allow for sufficient time to generate the data needed. We have already described the potential for registries, but we recommend in addition to conduct an early economic evaluation of phase II data, which may provide timely knowledge on pricing and reimbursement [75]. Furthermore, patient organisations may be able to support reimbursement efforts, as there should be a mutual interest to bring orphan drugs to the market.

Another opportunity is risk-sharing agreements. Decision makers have implemented alternative methods of financing in response to high uncertainty for interventions, for example, future clinical and economic outcomes for orphan drugs [76, 77]. In short, they are in place to facilitate risk sharing between those supplying (manufacturers) and paying (healthcare providers) for health interventions, which is why they have broadly been referred to as risk sharing, pay-for-performance or managed-entry agreements. Although the nomenclature is not consistent, they can generally be divided into two categories: health outcome-based or non-outcome-based agreements [78, 79].

6 Limitations

Our review has some limitations. First, two researchers conducted the screening of titles and abstracts, but only one reviewer conducted the full screening and quality assessment. For this reason, the reliability could have been higher. To make up for this, we transparently report the full screening and quality assessment in the ESM. Second, exclusion of studies that did not qualify as systematic reviews meant that there was a chance of missing valuable information. Such an example was a narrative review of orphan drugs, which could have supported our findings [9]. Moreover, the search only included studies from 2010. However, the literature searches were partly based on search filters, which balanced sensitivity and specificity. Third, we included all studies, no matter their quality rating, to maximise inputs into the study. This resulted in the inclusion of one study with a low-quality rating [31]. Fourth, advanced therapeutic medicinal products (ATMPs) were excluded from this umbrella review, even if they were considered orphan drugs. It has been much debated whether they should qualify as drugs because the production process typically involves modifying cells or genes. There are challenges for economic evaluations of ATMPs such as high prices and sparse supportive evidence, for example, small sample sizes, single-arm studies and insufficient follow-up [80]. Thus, the identified opportunities for orphan drugs could apply equally to them. However, there are likely differences, ATMPs are frequently curative with a one-off cost, which is why major challenges are affordability and long-term uncertainty [81,82,83]. Furthermore, it was previously suggested to consider economic aspects for curative and non-curative treatments differently [57]. Finally, cross-referencing in the included papers was most prominent in recent papers, and in those with a broader scope. For example, a review concerned with methods for assessment of orphan drugs included six references, whereas another review of economic evaluations for enzyme replacement therapy in lysosomal storage disease included none [32, 46].

7 Conclusions

This umbrella review set out to determine issues for the economic evaluation of orphan drugs. The most obvious finding to emerge from this study was scarcity of evidence for clinical effectiveness, costs, quality of life and natural history of the disease. Scarcity of evidence and publication bias emerged as possible causes for the limited quantity of economic evaluations from the literature. The results support the notion that an economic evaluation of rare diseases is challenging.

We recommend that researchers focus on sustainable initiatives and explore flexible cost-effectiveness models, for example, using living HTAs. We highlight that further research is required to determine the effect of publication bias on the ability to meet cost-effectiveness thresholds.

References

Grand T, Ren S, Thokala P, Oudin Åström D, Regnier S, Hall J. Issues, challenges and opportunities for economic evaluation of orphan drugs: an umbrella review protocol. 2023. The University of Sheffield’s research data repository. 2023. https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.23390060.v1.

Richter T, Nestler-Parr S, Babela R, Khan ZM, Tesoro T, Molsen E, Hughes DA. Rare disease terminology and definitions: a systematic global review: report of the ISPOR Rare Disease Special Interest Group. Value Health. 2015;18(6):906–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.05.008.

The European Parliament. Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 1999 on orphan medicinal products. 2000. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32000R0141&from=EN. Accessed 20 Oct 2022.

Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Orphan Drug Act. In: Senate and house of representatives of the United States of America in Congress, editor. 97th Congress: Public Law 97–114; 1983.

Thomas S, Caplan A. The orphan drug act revisited. JAMA. 2019;321(9):833–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.0290.

Miller KL, Lanthier M. Investigating the landscape of US orphan product approvals. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-018-0930-3.

Pulsinelli GA. The Orphan Drug Act: what’s right with It. Santa Clara High Technol Law J. 1999;15:2.

Miller KL, Fermaglich LJ, Maynard J. Using four decades of FDA orphan drug designations to describe trends in rare disease drug development: substantial growth seen in development of drugs for rare oncologic, neurologic, and pediatric-onset diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):265. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01901-6.

Ollendorf DA, Chapman RH, Pearson SD. Evaluating and valuing drugs for rare conditions: no easy answers. Value Health. 2018;21(5):547–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.01.008.

Department of Health. The UK strategy for rare diseases. 2023. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7c61d540f0b626628abaaa/UK_Strategy_for_Rare_Diseases.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 2023.

European Medicines Agency. Benefit-risk methodology. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/what-we-do/regulatory-science-research/benefit-risk-methodology. Accessed 25 Oct 2022.

Pearson I, Rothwell B, Olaye A, Knight C. Economic modeling considerations for rare diseases. Value Health. 2018;21(5):515–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.02.008.

Nestler-Parr S, Korchagina D, Toumi M, Pashos CL, Blanchette C, Molsen E, et al. Challenges in research and health technology assessment of rare disease technologies: report of the ISPOR Rare Disease Special Interest Group. Value Health. 2018;21(5):493–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.03.004.

York Health Economics Consortium. Health technology assessment. 2016. http://www.yhec.co.uk/glossary/health-technology-assessment/. Accessed 25 Oct 2022.

Dharssi S, Wong-Rieger D, Harold M, Terry S. Review of 11 national policies for rare diseases in the context of key patient needs. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-017-0618-0.

Forman J, Taruscio D, Llera VA, Barrera LA, Coté TR, Edfjäll C, et al. The need for worldwide policy and action plans for rare diseases. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(8):805–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02705.x.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. The Innovatives Medicines Fund principles. 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/B1686-the-innovate-medicines-fund-principles-june-2022.pdf. Accessed 27 Oct 2023.

Smith RA, Schneider PP, Mohammed W. Living HTA: automating health technology assessment with R. Wellcome Open Res. 2022;7:194. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.17933.1.

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):132–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055.

Salleh S, Thokala P, Brennan A, Hughes R, Booth A. Simulation modelling in healthcare: an umbrella review of systematic literature reviews. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(9):937–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-017-0523-3.

Alsulamy N, Lee A, Thokala P, Alessa T. What influences the implementation of shared decision making: an umbrella review. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(12):2400–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.009.

De Freitas L, Goodacre S, O’Hara R, Thokala P, Hariharan S. Interventions to improve patient flow in emergency departments: an umbrella review. Emerg Med J. 2018;35(10):626–37. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2017-207263.

Booth A. Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library Hi Tech. 2006;24(3):355–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830610692127.

CADTH. Economic evaluations & models: MEDLINE. In: CADTH Search Filters Database. 2022. https://searchfilters.cadth.ca/link/16. Accessed 17 Nov 2022.

CADTH. Economic evaluations & models: Embase. In: CADTH Search Filters Database. 2022. https://searchfilters.cadth.ca/link/15. Accessed 23 Nov 2022.

SIGN. Systematic reviews. 2021. https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sign.ac.uk%2Fassets%2Fsearch-filters-systematic-reviews.docx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK. Accessed 10 Jan 2023.

Booth A, Sutton A, Papaioannou D. Searching the literature: systematic approaches to a successful literature review. New York: SAGE Publications; 2016. p. 110.

Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI critical appraisal checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses. 2017. https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Systematic_Reviews2017_0.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2024.

Sharif M, Sharif F, Ali H, Ahmed F. Systematic reviews explained: AMSTAR: how to tell the good from the bad and the ugly. Oral Health Dental Manage. 2013;12:9–16.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-7-10.

Lasalvia P, Prieto-Pinto L, Moreno M, Castrillon J, Romano G, Garzon-Orjuela N, Rosselli D. International experiences in multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) for evaluating orphan drugs: a scoping review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19(4):40920. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2019.1633918.

Mohammadshahi M, Olyaeemanesh A, Ehsani-Chimeh E, Mobinizadeh M, Fakoorfard Z, Akbari Sari A, Aghighi M. Methods and criteria for the assessment of orphan drugs: a scoping review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2022;38(1):e59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462322000393.

Abdallah K, Huys I, Claes K, Simoens S. Methodological quality assessment of budget impact analyses for orphan drugs: a systematic review. Front Pharmacol. 2021;2021:12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.630949.

Angelis A, Tordrup D, Kanavos P. Socio-economic burden of rare diseases: a systematic review of cost of illness evidence. Health Policy. 2015;119(7):964–79.

Babac A, Damm K, Graf von der Schulenburg JM. Patient-reported data informing early benefit assessment of rare diseases in Germany: a systematic review. Health Econ Rev. 2019;9(1):34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-019-0251-9.

Baran-Kooiker A, Czech M, Kooiker C. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) models in health technology assessment of orphan drugs: a systematic literature review. Next steps in methodology development? Front Public Health. 2018;6:287. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00287.

Chen T, Chen J, Chen C, Zheng H, Chen Y, Liu M, Zheng B. Systematic review and cost-effectiveness of bosentan and sildenafil as therapeutic drugs for pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(7):2250–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.25427.

Cheng MM, Ramsey SD, Devine EB, Garrison LP, Bresnahan BW, Veenstra DL. Systematic review of comparative effectiveness data for oncology orphan drugs. Am J Manage Care. 2012;18(1):47–62.

Dhawan A, Lawlor MW, Mazariegos GV, McKiernan P, Squires JE, Strauss KA, et al. Disease burden of Crigler-Najjar syndrome: systematic review and future perspectives. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;35(4):530–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.14853.

Faulkner E, Spinner DS, Ringo M, Carroll M. Are global health systems ready for transformative therapies? Value Health. 2019;22(6):627–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.1911.

Friedmann C, Levy P, Hensel P, Hiligsmann M. Using multi-criteria decision analysis to appraise orphan drugs: a systematic review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(2):135–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2018.1414603.

Garcia-Perez L, Linertova R, Valcarcel-Nazco C, Posada M, Gorostiza I, Serrano-Aguilar P. Cost-of-illness studies in rare diseases: a scoping review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01815-3.

Gruhn S, Witte J, Greiner W, Damm O, Dietzsch M, Kramer R, Knuf M. Epidemiology and economic burden of meningococcal disease in Germany: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2022;40(13):1932–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.043.

Jakes RW, Kwon N, Nordstrom B, Goulding R, Fahrbach K, Tarpey J, Van Dyke MK. Burden of illness associated with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(12):4829–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-021-05783-8.

Kanters TA, de Sonneville-Koedoot C, Redekop WK, Hakkaart L. Systematic review of available evidence on 11 high-priced inpatient orphan drugs. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:124. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-8-124.

Katsigianni EI, Petrou P. A systematic review of economic evaluations of enzyme replacement therapy in Lysosomal storage diseases. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2022;20(1):51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-022-00369-w.

Knoble N, Nayroles G, Cheng C, Arnould B. Illustration of patient-reported outcome challenges and solutions in rare diseases: a systematic review in Cushing’s syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):228. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-018-0958-4.

Kwon CS, Daniele P, Forsythe A, Ngai C. A systematic literature review of the epidemiology, health-related quality of life impact, and economic burden of immunoglobulin A nephropathy. J Health Econ Outcomes Res. 2021;8(2):36–45. https://doi.org/10.36469/001c.26129.

Picavet E, Cassiman D, Simoens S. What is known about the cost-effectiveness of orphan drugs? Evidence from cost-utility analyses. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40(3):304–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12271.

Querol L, Crabtree M, Herepath M, Priedane E, Viejo Viejo I, Agush S, Sommerer P. Systematic literature review of burden of illness in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). J Neurol. 2021;268(10):3706–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09998-8.

Raut M, Singh G, Hiscock I, Sharma S, Pilkhwal N. A systematic literature review of the epidemiology, quality of life, and economic burden, including disease pathways and treatment patterns of relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2022;15(7):607–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17474086.2022.2080050.

Rice J, White A, Scarpati L, Philbin M, Wan G, Nelson W. Burden of noninfectious inflammatory eye diseases: a systematic literature review. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2018;23(3):S67. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2018.1512961.

Schlander M, Dintsios CM, Gandjour A. Budgetary impact and cost drivers of drugs for rare and ultrarare diseases. Value Health. 2018;21(5):525–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.10.015.

Short H, Stafinski T, Menon D. A national approach to reimbursement decision-making on drugs for rare diseases in Canada? Insights from across the ponds. Healthc Policy. 2015;10(4):24–46.

Weidlich D, Kefalas P, Guest JF. Healthcare costs and outcomes of managing beta-thalassemia major over 50 years in the United Kingdom. Transfusion. 2016;56(5):1038–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.13513.

Zelei T, Mendola ND, Elezbawy B, Nemeth B, Campbell JD. Criteria and scoring functions used in multi-criteria decision analysis and value frameworks for the assessment of rare disease therapies: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoecon Open. 2021;5(4):605–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-021-00271-w.

Zelei T, Molnar MJ, Szegedi M, Kalo Z. Systematic review on the evaluation criteria of orphan medicines in central and eastern European countries. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11(1):72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-016-0455-6.

Lee C, Lam A, Kangappaden T, Olver P, Kane S, Tran D, Ammann E. Systematic literature review of evidence in amyloid light-chain amyloidosis. J Comp Eff Res. 2022;11(6):451–72. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2021-0261.

Leonart LP, Borba HHL, Ferreira VL, Riveros BS, Pontarolo R. Cost-effectiveness of acromegaly treatments: a systematic review. Pituitary. 2018;21(6):642–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-018-0908-0.

Onakpoya IJ, Spencer EA, Thompson MJ, Heneghan CJ. Effectiveness, safety and costs of orphan drugs: an evidence-based review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e007199. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007199.

Park T, Griggs SK, Suh DC. Cost Effectiveness of monoclonal antibody therapy for rare diseases: a systematic review. BioDrugs. 2015;29(4):259–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-015-0135-4.

Schuller Y, Hollak CE, Biegstraaten M. The quality of economic evaluations of ultra-orphan drugs in Europe: a systematic review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-015-0305-y.

Sequeira AR, Mentzakis E, Archangelidi O, Paolucci F. The economic and health impact of rare diseases: a meta-analysis. Health Policy Technol. 2021;10(1):32–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2021.02.002.

Thorat T, Neumann PJ, Chambers JD. Hemophilia Burden of Disease: A systematic review of the cost-utility literature for hemophilia. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(7):632–42. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.7.632.

Woersching AL, Borrego ME, Raisch DW. Assessing the quality of economic evaluations of FDA novel drug approvals: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(12):1028–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028016662893.

Plüddemann A, Banerjee A, O’Sullivan J. Positive results bias. 2017. https://catalogofbias.org/biases/positive-results-bias/. Accessed 19 Jun 2023.

Holman B, Bero L, Mintzes B. Industry sponsorship bias. 2019. https://catalogofbias.org/biases/industry-sponsorship-bias/. Accessed 24 Jun 2023.

Caro JJ, Briggs AH, Siebert U, Kuntz KM. Modeling good research practices–overview: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-1. Med Decis Making. 2012;32(5):667–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x12454577.

Briggs AH, Weinstein MC, Fenwick EAL, Karnon J, Sculpher MJ, Paltiel AD. Model parameter estimation and uncertainty: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-6. Value Health. 2012;15(6):835–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2012.04.014.

Mauskopf JA, Sullivan SD, Annemans L, Caro J, Mullins CD, Nuijten M, et al. Principles of good practice for budget impact analysis: report of the ISPOR Task Force on good research practices–budget impact analysis. Value Health. 2007;10(5):336–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00187.x.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE health technology evaluations: the manual 2022. 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg36/chapter/committee-recommendations. Accessed 11 Nov 2023.

Thokala P, Srivastava T, Smith R, Ren S, Whittington MD, Elvidge J, et al. Living health technology assessment: issues, challenges and opportunities. Pharmacoeconomics. 2023;41(3):227–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01229-4.

Smith R, Schneider P. Making health economic models Shiny: a tutorial. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:69. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15807.2.

Kunst N, Burger EA, Coupé VMH, Kuntz KM, Aas E. A guide to an iterative approach to model-based decision making in health and medicine: an iterative decision-making framework. Pharmacoeconomics. 2024;42(4):363–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-023-01341-z.

Ramsey SD, Willke RJ, Glick H, Reed SD, Augustovski F, Jonsson B, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials II: an ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force Report. Value Health. 2015;18(2):161–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.02.001.

Drummond M. When do performance-based risk-sharing arrangements make sense? Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(6):569–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-015-0683-z.

Facey KM, Espin J, Kent E, Link A, Nicod E, O’Leary A, et al. Implementing outcomes-based managed entry agreements for rare disease treatments: nusinersen and tisagenlecleucel. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(9):1021–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-021-01050-5.

Ferrario A, Kanavos P. Dealing with uncertainty and high prices of new medicines: a comparative analysis of the use of managed entry agreements in Belgium, England, the Netherlands and Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 2015;124:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.003.

Carlson JJ, Sullivan SD, Garrison LP, Neumann PJ, Veenstra DL. Linking payment to health outcomes: a taxonomy and examination of performance-based reimbursement schemes between healthcare payers and manufacturers. Health Policy. 2010;96(3):179–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.02.005.

Gladwell D, Ciani O, Parnaby A, Palmer S. Surrogacy and the valuation of ATMPs: taking our place in the evidence generation/assessment continuum. Pharmacoeconomics. 2024;42(2):137–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-023-01334-y.

Angelis A, Naci H, Hackshaw A. Recalibrating health technology assessment methods for cell and gene therapies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(12):1297–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00956-w.

Coyle D, Durand-Zaleski I, Farrington J, Garrison L, Graf-von-der-Schulenburg JM, Greiner W, et al. HTA methodology and value frameworks for evaluation and policy making for cell and gene therapies. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(9):1421–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01212-w.

Fiorenza S, Ritchie DS, Ramsey SD, Turtle CJ, Roth JA. Value and affordability of CAR T-cell therapy in the United States. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55(9):1706–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-020-0956-8.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Anthea Tucker, librarian at the University of Sheffield, for valuable inputs on search strategies. The PROSPERO administration team confirmed that this review was not eligible for registration. Instead, the protocol for this umbrella review was made available in preprint before data extraction commenced [1]. It is available from University of Sheffield’s online data repository. License: CC BY 4.0; https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.23390060; URL: Issues, challenges and opportunities for economic evaluation of orphan drugs: an umbrella review protocol (shef.ac.uk).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Tobias Sydendal Grand is an industrial PhD candidate at the University of Sheffield sponsored by Innovation Fund Denmark (case number: 2040-00017B) and Lundbeck A/S.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

Tobias Sydendal Grand, Shijie Ren, James Hall, Daniel Oudin Åström, Stephane Regnier and Praveen Thokala have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Code Availability

The code used to create a PRISMA compliant flow diagram in Fig. 1 is available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8232536. The code used to create an interactive version of Fig. 2 data extraction themes, sub-topics and findings is available from: https://tobiasgrand.github.io/-data-extraction-themes.github.io/ and files are available from: https://zenodo.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10201217.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by TSG. JH was a second reviewer, hence assisted with the screening of papers. The first draft of the manuscript was written by TSG, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grand, T.S., Ren, S., Hall, J. et al. Issues, Challenges and Opportunities for Economic Evaluations of Orphan Drugs in Rare Diseases: An Umbrella Review. PharmacoEconomics 42, 619–631 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-024-01370-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-024-01370-2