Abstract

Background

Compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects may affect productivity losses due to illness, disability, or premature death of individuals. Hence, they are important in estimating productivity losses and productivity costs in the context of economic evaluations of health interventions. This paper presents a systematic literature review of papers focusing on compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects, as well as whether and how they are included in health economic evaluations.

Methods

The systematic literature search was performed covering EconLit and PubMed. A data-extraction form was developed focusing on compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects.

Results

A total of 26 studies were included. Of these, 15 were empirical studies, three studies were methodological studies, two studies combined methodological research with empirical research, four were critical reviews, one study was a critical review combined with methodological research, and one study was a cost–benefit analysis. No uniform definition of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects was identified. The terminology used to describe compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects varied as well. While the included studies suggest that both multipliers as well as compensation mechanisms substantially impact productivity cost estimates, the available evidence is scarce. Moreover, the generalizability as well as validity of assumptions underlying the calculations are unclear. Available measurement methods for compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects differ in approaches and are hardly validated.

Conclusion

While our review suggests that compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects may have a significant impact on productivity losses and costs, much remains unclear about their features, valid measurement, and correct valuation. This hampers their current inclusion in economic evaluation, and therefore, more research into both phenomena remains warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The systematic review highlights the importance of considering compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in health economic evaluations. Both factors have been found to significantly impact productivity cost estimates. Decision makers should recognize the potential influence of these factors on productivity losses and costs. |

Despite recognizing the importance of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects, the review points out unresolved methodological issues in their estimation. The evidence currently available showed a wide range of estimated impacts with varying assumptions and contextual factors. Decision makers should be cautious when interpreting these factors in economic evaluations due to the lack of clear understanding and consistent evidence. |

The review highlights the need for further research and methodological development to address the limitations and uncertainties associated with the impact of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects. Decision makers should prioritize supporting research efforts aimed at clarifying the definitions, identification, measurement, and valuation of these factors. This may include qualitative research to understand the dynamics of absenteeism, presenteeism, and productivity in different contexts, as well as the development of standardized measurement instruments and methodologies for accurate estimation. Improved methodologies will enable valid inclusion of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in economic evaluations, leading to better-informed health policy decisions. |

1 Introduction

Rising healthcare expenditures pose an important challenge to policymakers. Faced with limited healthcare budgets, ageing populations, increased demand for healthcare, and increasing treatment possibilities, decisions need be made about which interventions can be funded or reimbursed in collectively financed health systems [1,2,3,4]. Hence, there is a growing interest in health economic evaluation as a tool supporting such difficult decisions. Health economic evaluation is defined as a comparative analysis of alternative interventions in terms of their costs and benefits and, essentially, provides insights into the cost-effectiveness or value an intervention offers compared to a relevant comparator [3, 5]. The most common type of health economic evaluation is cost-utility analysis (CUA), in which health outcomes are expressed in quality-adjusted life-years. The exact operationalization of CUA varies across jurisdictions and typically strongly depends on national guidelines for health economic evaluations [6]. An important difference between such guidelines is which perspective is prescribed to be taken in the evaluation. Often, either a healthcare (or public payer) perspective or a societal perspective is prescribed. When a health economic evaluation is performed from a healthcare perspective, broadly speaking, only costs falling on the healthcare budget are taken into account and only health effects are seen as relevant benefits. The underlying goal of the policymaker is then assumed to be to maximize health benefits from a given healthcare budget. When a health economic evaluation is performed from the societal perspective, all relevant societal costs and benefits are taken into account, regardless of who pays the costs and who receives the benefits [7,8,9]. The underlying goal of the policymaker is then assumed to be to ultimately maximize social welfare through allocation decisions. The societal perspective may be seen as conforming more closely with the welfare economic roots of economic evaluation, although it may still be operationalized in line with extra-welfarism [10, 11]. Given the aim of health economic evaluations to inform actual healthcare decisions, it is important that their methodology is clear and justified.

An important example of such a methodological issue is that of the measurement and valuation of productivity costs. Productivity costs are defined as costs related to a person’s productivity loss of paid and unpaid work due to disease resulting from illness, disability, or premature death of productive individuals [12]. When taking a societal perspective, these productivity costs should be included in a health economic evaluation whenever productivity is expected to be relevantly affected by the intervention. Productivity costs have been shown to be a significant part of total costs in many economic evaluations and can have a profound impact on the final cost-effectiveness ratio [13, 14]. This highlights the importance of accurate estimation of productivity costs, which has been shown to be quite challenging in terms of their identification, measurement, and valuation [15,16,17,18,19,20].

Estimates of productivity costs typically focus on paid work and, within that context, especially on production losses related to absenteeism from work. Increasingly, productivity costs due to presenteeism (being less productive while at paid work due to health problems) are also included, which may become more important as working from home becomes more common [21]. Moreover, productivity costs related to unpaid work still receive little attention—both methodologically and in actual economic evaluations [22].

In estimating productivity costs due to absenteeism and presenteeism in paid work, important unresolved issues remain. Next to debates about valuation methods (e.g., the human capital versus the friction cost method) [23,24,25], this also pertains to the impact of so-called multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms on production losses and productivity costs.

Multiplier effects can be described as the effects on overall or ‘team output’ due to absenteeism or presenteeism of a worker with health problems [18]. To illustrate, consider a software development team in which a key developer with unique knowledge is absent due to illness. In that case, the full development team may be less productive due to interdependencies in the development process. Multiplier effects are relevant in this example as the reduced productivity or absence of one individual negatively affects the productivity of others, leading to a larger overall loss in productivity.

Compensation mechanisms are described as compensation for lost labor, referring to situations in which a person’s work is compensated [17, 18, 28, 29]. For example, if an employee is absent from work due to a health problem, his or her colleagues, or temporary hires, may take over certain tasks in order to keep the production levels constant. In certain types of jobs, it may also be possible for the absent employee to make up for lost work after his or her return to work. In such cases, compensation mechanisms mitigate the production losses due to absence.

Regarding multiplier effects, it has been argued that conventional estimates of productivity losses at the individual level may underestimate total productivity losses, as reduced productivity of one person may negatively affect the productivity of others [26]. Compensation mechanisms, on the other hand, refer to a potential overestimation of production losses, since the absence or presenteeism of a worker with health problems may be compensated by colleagues, temporary workers, or the ill employee him- or herself at a later moment [27]. This compensating for otherwise lost work obviously reduces production losses. Whether it also reduces productivity costs depends on the costs of the compensation mechanisms themselves [30].

One of the unresolved issues in measuring productivity losses and costs is how to deal with multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms in calculating productivity losses and costs in health economic evaluations. Due to measurement challenges, compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects are usually not included in such evaluations, despite their potential influence on productivity cost estimates and final cost-effectiveness results. [13, 16, 20, 31]. Neglecting compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in the measurement of productivity losses and costs may lead to inaccurate estimation of the cost-effectiveness outcomes, which may ultimately lead to incorrect policy decisions.

Currently, the underlying mechanisms of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects as well as whether and how they influence productivity losses and costs are understudied [16, 18, 27]. Understanding how compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects should be identified, measured, and valued, as well as what their impact is on productivity losses and costs, remains important. Although previous research has studied the inclusion of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in health economic evaluations, clear guidance on whether and how to consider multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms in this context is lacking [17]. The current study, therefore, aims to provide an overview of the currently available literature focusing on compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects, as well as on their impact on productivity cost estimates.

2 Methods

2.1 Databases and Key Concepts

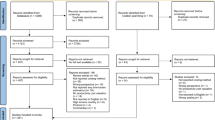

Studies focusing on compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects were identified through a systematic literature search. A systematic search was conducted in the electronic bibliographic databases of EconLit and PubMed, in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [32].

The search strategy included the following keywords: (1) compensation mechanisms or multiplier effects, (2) productivity costs or productivity losses, and (3) identification, measurement, validation, or impact. Also, synonyms of multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms were used in the search strategy, such as team output and team effect. The search queries are presented in the appendix. The searches were conducted on February 28, 2023.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they were written in English and their full text was available. Moreover, they needed to meet one or more of the following inclusion criteria, evaluated first based on title and abstract:

-

1.

Multiplier effects or compensation mechanisms were mentioned.

-

2.

Measurement methods of multiplier effects or compensation mechanisms were investigated or mentioned.

-

3.

Factors influencing multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms were investigated.

-

4.

The impact of multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms on costs and productivity losses was investigated.

Systematic reviews were excluded, but their references were screened for relevant literature. Additionally, reference lists of included studies were reviewed for relevant additional literature.

2.3 Study Selection

First, all duplicated studies were removed from the identified studies in EconLit and PubMed using the EndNote de-duplicate function. Second, titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies were examined for relevance based on the above-specified inclusion criteria by two researchers independently (NH and KH). In case of unclarity or uncertainty, inclusion or exclusion was discussed between NH and KH. In case of doubt, the study was included for full-text review. Finally, full texts were obtained after the selection based on titles and abstracts. NH assessed whether the full-text studies met the inclusion criteria. In case of doubt, inclusion was discussed with LH. Furthermore, the reference lists of the selected studies and of the excluded systematic reviews were manually searched for potentially relevant additional literature by NH. Full-text extractions were independently conducted by three reviewers (LH, MK, NH). Disagreements were resolved by discussion between two or three of the reviewers (LH, MK, NH).

2.4 Data Extraction and Analysis

A data extraction form was developed to extract relevant data from the selected studies regarding compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects. The following general aspects were extracted from the studies: title, authors, and year of publication. Also, the type of study was extracted, for instance, whether papers reported on an empirical study, a critical review or a study developing, or refining methodology. The latter was labeled as a methodological study. In addition, objectives, general methods applied in the included studies, and information on the role of multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms were collected, such as how these were identified, measured, and valued, and their impact on productivity losses and costs. Next, the conclusions and recommendations that were presented in the papers regarding multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms were extracted.

3 Results

3.1 Study Selection

A total of 2355 unique articles were identified from PubMed and EconLit. After title and abstract screening, 248 full-text papers were examined. Of these, 22 met the inclusion criteria. Additionally, four studies were added to the study after reviewing the reference lists of the excluded systematic reviews and the 22 already included studies. This resulted in a total of 26 included studies. The PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic review is shown in Fig. 1.

3.2 Literature Overview

Table 1 provides an overview of the studies included in this review, listed in chronological order to illustrate how the research has evolved over time. The first identified study addressing compensation mechanisms was published in 1998, and the first study reporting on multiplier effects originates from 2002 [26, 29].

The 26 included studies were a mix of methodological papers, empirical studies, and critical reviews. Of these 26 studies, 15 were empirical studies aiming to estimate compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in different contexts [18, 28, 29, 33, 36, 38, 39, 42, 46,47,48,49, 51,52,53], two studies combined methodological research with empirical research [19, 42], three studies were methodological studies [17, 26, 35], four were critical reviews [16, 27, 34, 40], one study was a critical review combined with methodological research [37], and one study was a cost–benefit analysis [45].

3.3 Definitions and Terminology

No clear uniform definition or operationalization of compensation mechanisms was observed in the identified literature. In their 1998 paper, Severens and colleagues operationalized compensation mechanisms by distinguishing between six different compensation mechanisms [29]:

-

1.

Compensation by colleagues during normal working hours.

-

2.

Compensation by colleagues during extra working hours.

-

3.

Compensation by extra temporary workers.

-

4.

Self-compensation during normal working hours.

-

5.

Self-compensation during extra working hours.

-

6.

No compensation for lost work and compensation mechanisms unknown.

In the included studies, compensation mechanisms were discussed descriptively, i.e., describing how through which mechanisms lost productivity was partially or fully compensated for. Compensation mechanisms can take different forms, such as colleagues taking on additional work, the use of temporary staff or contractors, or the absent employee compensating for lost work after his or her return to work, in normal or additional working hours. Additionally, compensation may involve changes in work schedules, work processes, or the allocation of resources to minimize the impact of the absenteeism on overall productivity.

It should be noted that certain compensation mechanisms may also have additional costs associated with them, for instance, when hiring temporary staff. This compensation may not always fully offset production losses [16,17,18, 27, 28, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. The majority of included studies used the term ‘compensation mechanisms’ [13, 16,17,18, 27, 28, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. One study used the term ‘compensation methods’ instead [42].

Similarly, no uniform definition of multiplier effects was encountered in the included papers. Nicholson and colleagues define multipliers “as the cost of an absence as a proportion (often greater than one) of the absent worker’s daily wage” [19]. Pauly and colleagues do not provide a definition but describe that “health-related impact on productivity, measured relative to the average daily paid wage of a worker, can be several multiples of that wage in some jobs, but not in others, depending on job characteristics” [43]. Similar descriptions were used in ten studies [26, 34, 35, 38, 39, 42, 44,45,46,47]. In seven studies, multiplier effects were described as the impact of a worker’s absenteeism or presenteeism on the productivity of co-workers [16,17,18, 27, 28, 37, 38]. The terminology used to describe multiplier effects differed across the identified articles. The term multiplier effects was used in seven studies [16,17,18, 27, 37, 42, 46]. Productivity spillovers, team member dependency, and team dependency were each reported in one study [42, 48, 49]. Arcidiacono et al. (2017) describe multiplier effects as workers who can bring out the best in other co-workers and, hence, boost peer productivity [48]. Rost et al. (2014) make the distinction between team member dependency and team dependency [42]. In case of team member dependency, a worker is dependent on a colleague’s work to fulfill his or her own task, but not necessarily the other way around. In case of team dependency, workers’ performance within teams is interdependent and, therefore, the dependency is not one-sided [42].

3.4 Critical Reviews

All four identified critical reviews, as well as the critical review with methodological research, addressed broader methodological challenges related to productivity cost estimation in (health) economic evaluations; compensation mechanisms and/or multiplier effects were subtopics in these reviews. In all reviews, it was stipulated that compensation mechanisms and/or multiplier effects can be important in this context. The oldest of these reviews was published in 2005 and the most recent ones in 2013 [16, 27, 40]. One review also included methodological research, i.e., the development of a productivity costs measurement instrument (the PROductivity and DISease Questionnaire [PRODISQ]) [37, 50]. This instrument includes a module for measuring compensation mechanisms. This review advocated the inclusion of compensation mechanisms in health economic evaluations, but also argued that more research investigating the simultaneous inclusion of different types of compensation mechanisms is required [37]. Importantly, the paper also highlighted that using the compensation mechanisms module and estimates of productivity losses that were corrected for compensation mechanisms would result in a ‘conservative’ estimate of productivity costs. All but one review expressed the importance of more research into the measurement and valuation of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in order to allow their inclusion in health economic evaluations. Krol and colleagues for instance concluded that many questions remain unanswered regarding compensation mechanisms, multiplier effects and their interaction, which hampers their inclusion in economic evaluation [16].

3.5 Methodological Research

Of the six papers (also) presenting methodological research, three studies focused purely on estimating multiplier effects, two studies described the development of an instrument for measuring productivity costs, and one paper aimed to offer guidance on how to measure and value productivity costs in economic evaluations [17, 19, 26, 35, 37, 43].

The first paper on multiplier effects by Pauly et al. from 2002 provided a theoretical rationale for the importance ofFootnote 1 multiplier effects. The paper described three factors influencing the magnitude of multiplier effects: (1) the extent to which the work is team oriented rather than individually oriented, (2) the costs associated with replacing an absent worker, and (3) the magnitude of consequences of a decrease of productive output of a worker [26]. The second study on multiplier effects, by Nicholson et al. (2006), provided a conceptual model explaining how the consequences of an employee’s reduced productivity can be larger in certain jobs than the wage of the employee suggests. In addition, based on a survey among 804 managers in the United States, multipliers were estimated for a total of 35 professions, both for a 3-day and a 2-week period of absence [19]. These multipliers can be used to adjust traditional productivity loss estimates to also reflect the diminished productive output of team members, above and beyond what is already reflected in the wage of the worker with health problems. With these multipliers, it is possible to calculate the full effect of a co-worker’s reduced productivity in relation to relevant work characteristics of the ill-worker. With reliable and generalizable multipliers, the calculation of full productivity costs would be possible with only individual data and information about the job of the worker with health problems, without direct measurement. The calculated multipliers varied between 1 (for a fast-food cook, based on responses of six managers) and 11.4 (for a construction engineer, based on eight manager responses) [17]. The median multiplier was 1.28. The third methodological study investigating multiplier effects was similar to the second [43]. However, in this study, multiplier effects related to both absenteeism and presenteeism were considered. Based on a survey among 790 managers, absenteeism and presenteeism multipliers were presented for 22 different professions. Multipliers ranged from 1.05 (auto service technicians and hotel maids, based on 19 and 22 observations, respectively) to 2.04 (engineers, based on 25 observations).

Two papers described the development of measurement instruments for productivity costs [35, 37]. One only included a compensation mechanisms module (the PRODISQ) [37], while another one included questions pertaining to both compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects (the Valuation of Lost Productivity [VOLP] questionnaire) [35]. The PRODISQ included a compensation mechanisms module. As previously stated, the authors indicated that when using this module, the resulting productivity cost estimates should be considered as ‘conservative’ estimates [37]. The VOLP includes questions about job characteristics to develop multipliers for absenteeism and presenteeism [35, 37], similarly as done in the research of Pauly et al. However, it bases the estimates on employee rather than manager responses [37, 43]. In the paper reporting the development of the VOLP, multipliers were also presented for several professions. Nevertheless, since the sample size was small, multipliers per job type were based on only one to 11 responses per job type [35, 37]. The compensation mechanisms questions in the VOLP questionnaire ask whether work was (partly) taken over by colleagues or temporary workers, or postponed. The way the questions were phrased does not directly allow for compensation mechanism-specific adjustments of productivity cost estimates [35, 37].

The final methodological paper included in this review consisted of a guidance document for productivity cost identification, measurement, and valuation in the context of health economic evaluations [17]. The authors only briefly discuss compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects, but advise to not yet include compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in health economic evaluations until more research in this field has been conducted [17].

3.6 Empirical Research

In total, we retrieved 18 studies conducting empirical research including estimations of compensation mechanisms and/or multiplier effects. A general description of the objectives and methods of these studies can be found in Table 1. Five of these studies addressed compensation mechanisms [28, 29, 33, 36, 46], ten addressed multiplier effects [19, 26, 39, 43, 45, 47, 48, 51,52,53], and only three included both compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects [18, 38, 42].

The five studies only considering compensation mechanisms included four exploratory studies investigating how lost productivity was compensated and whether applied compensation mechanisms varied with duration of absenteeism and between countries [28, 29, 33, 36]. Two of these studies (Severens and colleagues, 1998, and Jacob-Tacken and colleagues, 2005) explored the impact of accounting for compensation mechanisms on productivity cost estimates [29, 36]. In those studies, about 25–30% of conventionally estimated productivity costs remained after accounting for compensation mechanisms. Note that these ‘naïve calculations’ assumed that compensating lost work during regular work hours by the ill employee or colleagues would not involve any additional costs—an assumption that has been criticized [26, 33]. The fifth empirical study only including compensation mechanisms, aimed to estimate productivity costs in rheumatoid arthritis and included a compensation mechanisms module [46].

Three of the ten empirical studies only including multiplier effects were studies investigating team or co-worker dependencies outside of the context of health economic evaluations [48, 49, 51]. These studies all concluded that an employee’s productivity partly depends on the productivity of colleagues. Five empirical studies estimated multipliers for absenteeism and/or presenteeism for different job types in order to allow their application in the health economic evaluations [19, 39, 43, 47, 52]. One study applied a median multiplier of 1.28 taken from an earlier study [19, 53]. Finally, one cost–benefit analysis examined treatment of depression and used multipliers for three different job types [45]. The study concluded that depression treatment offered more value for money in jobs characterized by team production, expensive substitutes, and/or important consequences of diminished productive output.

Three studies included both compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects [18, 38, 42]. Krol and colleagues investigated the impact of simultaneously correcting for compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects [18]. When only ‘naively’ correcting for compensation mechanisms, productivity cost estimates were 57% lower than conventionally calculated productivity costs. When correcting for both compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects, estimates were still 29% lower than conventionally calculated productivity costs [18]. Rost and colleagues also investigated the impact of including both compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects on productivity cost estimates [42]. They included compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects separately [42], and their results indicated a 5% increase of conventional cost estimates when correcting for multiplier effects and a 50% reduction when ‘naively’ correcting for compensation mechanisms [42]. Hanly et al. reported that applying multipliers resulted in an increase in productivity costs of 41–45%. The combined analysis with compensation mechanisms and multipliers was presented in supplementary material, which we were not able to access [38].

3.7 Recommendations

When it comes to the inclusion of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in health economic evaluations, the papers included in this review provided several recommendations. Most of the papers that were conducted in the context of health economic evaluations acknowledge the potential relevance and influence of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects and that they could be measured and included [17, 28, 38, 47]. Several studies provide more explicit recommendations. For instance, Koopmanschap and colleagues (2005) advised to include the compensation mechanisms module of the PRODISQ measurement instrument in economic evaluations [27]. Moreover, Knies et al. (2013) suggest that the inclusion of compensation mechanisms could be recommended in health economic guidelines [28]. Strömberg et al. (2017) recommended including multiplier effects in economic evaluations from the employer perspective [47]. On the other hand, for instance Rost et al. (2014) stated that the methodology to include compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects is still work in progress [42]. Similarly, Krol and Brouwer (2014) recommended to not include compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in productivity cost estimates until further research is conducted and, therefore, both effects can be included with more precision and certainty [17]. In line with this, Hanly et al. (2019) recommended not including compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in the base case [38].

4 Discussion

While including productivity costs in economic evaluations of health interventions can be impactful, important unresolved methodological issues remain regarding their estimation. Whether and how to adjust productivity costs for compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects is an important example. This systematic review focused on this issue and identified 26 papers with a focus on compensation mechanisms, multiplier effects, or both. These papers consist of a mix of methodological papers, empirical studies, and critical reviews.

The included studies showed that both compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects are important to include in health economic evaluations. Although scarce, the available evidence suggests that both compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects can greatly affect productivity cost estimates. However, the current evidence shows a broad range of estimated impact in different contexts and with varying underlying assumptions. Consequently, it is still largely unclear how compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects affect ultimate productivity costs. In addition, little is known about how multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms interact, as they are often studied independently from each other.

There are, however, limitations in this review that should be addressed. The current study faced several general limitations, such as the search strings used, the fact that our search was limited to PubMed and EconLit, and the fact that we focused on published papers in English. These issues may have resulted in incomplete identification of relevant studies and publications. Additionally, the inclusion criteria were restricted to titles and abstracts. This again may have limited the number of relevant articles identified. This means that studies discussing or reporting on compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects without specifically alluding to this in the title or abstract were not included in this review. Therefore, our results need to be interpreted within that context.

To our knowledge, this review is the first paper that systematically reviewed and classified what has been published to date on compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects. As it appears that there is no clear definition on what compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects are, we propose the following working definitions:

-

Compensation mechanisms are ways in which the consequences of the reduced productivity of a worker due to health problems are avoided or mitigated.

-

Multiplier effects can be defined as the impact of the reduced productivity of a worker due to health problems on the productivity of co-workers.

Nevertheless, there are still multiple questions to be answered regarding the identification, measurement, and valuation of both compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects. Regarding the identification of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects, current evidence suggests that both may well be relevant in estimating productivity losses in economic evaluations. However, the exact influence of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects on productivity losses and, subsequently, costs remains underexplored. The actual impact of compensation of lost productivity and of team dependencies on productivity on the team or firm level has not been investigated. More knowledge in this area is important. First explorations may take the form of further broad qualitative research with dyads of managers, employers, and (co-)workers in different work settings to explore what actually happens with productivity and productive output of individuals, their co-workers, and the firm when individuals face health issues at work, or when they are absent. This most likely will be related to job type and function, as well as firm, sector, and labor market characteristics. Based on this qualitative research a conceptual modelFootnote 2 could be developed. This model should not only describe the types of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects, but also the pathways of impact of health problems on productivity and productivity costs. This will help guide additional research.

Regarding the measurement of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in the context of health economic evaluations, it is still unclear exactly what to measure and how to measure it. Although there are measurement instruments available that include questions on compensation mechanisms and/or multiplier effects, such as the PRODISQ and the VOLP, these differ, and their modules on compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects have not been validated elaborately [17, 37]. This is even more important since these instruments are designed to be completed by the worker with health problems and it is not clear whether they have sufficient insight into how lost productivity is compensated, or whether and how their productivity losses affect the productivity of colleagues. Developing, refining, and validating measurement methods remains important. Alternative approaches, like developing general correction factors for multiplier effects, compensation mechanisms, or both, which could be applied more generally in economic evaluations, based on productivity cost estimations and patient job characteristics, can also be explored. Such an approach may be practical and, in general, appears promising, as mentioned in previous publications [19, 39, 43, 47]. However, such alternative approaches also need to be validated and well developed, for which, broader research is indispensable. Moreover, applying general correction factors to employee-specific productivity cost estimates may be troublesome. Commonly, productivity costs are based on average age and sex-dependent wages or actual wages. This information may not be specific enough to adequately apply correction factors, which may require more specificity in terms of function or work sector. Transferability of correction factors between jurisdictions also requires attention, since compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects may differ between countries and labor market arrangements [28].

Before using correction factors, the link between measurement and valuation needs to be clear. Our results highlight that much is unknown regarding how compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects affect actual productivity losses and, especially, related costs. This was also mentioned by, for instance, Bouwmans and colleagues [50], who wrote, “Empirical research has shown that coworkers often compensate productivity losses during regular hours […] and that absenteeism and presenteeism can negatively affect the productivity of coworkers in cases of team dependency […]. To what extent such mechanisms affect final production and actual costs, however, remains largely unclear.” For instance, in the currently limited amount of published explorative research, compensation of lost work in normal working hours by the employee or a co-worker has been assumed to be costless. From an economic point of view this is incorrect. If co-workers take over work in normal working hours, this may signal that a firm may have consciously created slack to be able to deal with absenteeism and reduced productivity. Such measures are, of course, not without costs. Research investigating the costs of compensation mechanisms is encouraged. If correction factors would be used to adjust production losses, they obviously would need to be adjusted to highlight the costs involved—or this should be dealt with separately.

In addition to potential compensation correction factors, the availability of reliable and generalizable multipliers would greatly facilitate calculating full productivity costs in economic evaluations. Such multipliers would ideally allow for the estimation of productivity losses beyond the affected individual, using only individual data and information about the worker's job, without the need for direct measurement of multipliers. Such information would be helpful in the context of economic evaluations of health interventions, but also provide more insight into the general economic impact of health problems.

Similarly, the translation of multipliers’ effects to productivity costs requires attention. Often, these multipliers are related to production losses in co-workers. However, the dependency of co-workers on the productivity of a worker with health problems may partly be reflected in the wage of the latter. Some publications indeed discussed multipliers in relation to the wage of absent workers [17, 23]. Only when the wages do not fully reflect these broader dependencies, adjustment based on multiplier effects is needed. The extent to which wages reflect co-workers’ dependencies also requires more attention in order to avoid double-counting dependencies in wages and multipliers. In this context, it is important to stress that research into the relationship between productivity losses and productivity costs in light of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects may be complex, especially in the context of professions in which objective productivity or productive output are hard to quantify. Moreover, the discussion on and investigation of multipliers and compensation mechanisms in the current literature seem to be primarily focused on the effects of absent workers within their own organization. However, it may be relevant to also consider broader potential impacts. For instance, production losses in one firm may be offset by increased output from another firm, which may represent a broader type of compensation. Likewise, reduced production in firm A may also lead to production losses in firm B if production in B depends on products from A, which would represent a broader type of multiplier. Quantifying such firm-transcending effects may be relevant but will impose new methodological challenges.

Finally, several studies have proposed ways to include compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in health economic evaluations. Some studies tested these methods in practice, but none of the identified studies (elaborately) tested the validity of the proposed methods [17]. It is, therefore, not surprising that most of the identified studies recommended that additional research is needed regarding the methodology of estimating and including compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in the context of health economic evaluations. Multiple issues regarding compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects still need to be investigated, in order to facilitate their inclusion in economic evaluations.

Given the limited amount of currently available evidence, as well as the remaining uncertainties regarding the size, scope, and generalizability of multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms and how they would translate into productivity costs, (advocating in favor of) including these elements in base-case analyses of economic evaluations seems premature. A structured approach would be used in developing an appropriate methodology and knowledge base. This may include qualitative research (e.g., interviewing employees with health problems as well as their colleagues and managers in a variety of work settings), which would improve our understanding of the dynamics of absenteeism, presenteeism, and productive input and output in different contexts. For instance, currently, in some studies, data were collected among employers and, in others, among employees. They might provide different estimates, but it is not clear whose estimates would be more accurate and whether this would differ in different work settings. Qualitative research could also provide more insight into what elements need to be measured and are relevant in the context of multipliers and compensation, which in turn may lead to intensified targeted quantitative empirical research. Ideally, this would be done with validated, standardized methods (also based on the qualitative insights) that can be used in different contexts. Current standardized measurement instruments will most likely not adequately capture all relevant aspects [52], implying that new instruments may need to be developed and validated. As a consequence, a better understanding of the costs of compensation mechanisms (e.g., costs of hiring and training temporary replacements) as well as multiplier effects (as these effects need not take place in people with similar wages to those of the absent employee) is also required in this context to be able to move from productivity losses to productivity costs.

The development of appropriate methodology enabling the reliable inclusion of multiplier effects and compensation mechanisms in economic evaluations remains important. By more precisely estimating production losses and productivity costs in economic evaluations from a societal perspective, policy decisions can be better informed.

5 Conclusion

This systematic review summarized the currently available literature focusing on compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects for use in health economic evaluations. Although the evidence is scarce, the potential relevance of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in estimating productivity losses seems clear. Nevertheless, much remains unknown about both phenomena, also in combination. Hence, the currently limited amount of evidence appears too weak to serve as a firm basis for the practical inclusion of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in health economic evaluations. To conclude, additional research leading to better tools and methodologies is needed in order to use compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in economic evaluations.

Notes

The PRODISQ was later replaced by the iMTA Productivity Costs Questionnaire (iPCQ). The iPCQ does not include CM or ME modules [37].

Note that Hubens and colleagues did not focus on compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects in their review of instruments, as it there was “insufficient clarity about how compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects influence overall productivity costs and to what extent employees are capable of estimating compensation or multipliers during their work absence” [54].

References

Bates LJ, Santerre RE. Does the US health care sector suffer from Baumol’s cost disease? Evidence from the 50 states. J Health Econ. 2013;32(2):386–91.

Hensher M, Tisdell J, Canny B, Zimitat C. Health care and the future of economic growth: exploring alternative perspectives. Health Econ Policy Law. 2020;15(4):419–39.

Rudmik L, Drummond M. Health economic evaluation: important principles and methodology. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(6):1341–7.

Wang F. More health expenditure, better economic performance? Empirical evidence from OECD countries. Inquiry. 2015;52:66.

Robinson R. Economic evaluation and health care. What does it mean? BMJ. 1993;307(6905):670–3.

Sharma D, Aggarwal AK, Downey LE, Prinja S. National healthcare economic evaluation guidelines: a cross-country comparison. Pharmacoecon Open. 2021;5(3):349–64.

Drummond M. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press,; 2015. Available from: Ebook central https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/oxford/detail.action?docID=4605509.

Shepard DS. Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. By M.R. Gold, J.E Siegel, L.B. Russell, and M.C. Weinstein (eds). New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 1999;2(2):91–2.

Brouwer W, van Baal P, van Exel J, Versteegh M. When is it too expensive? Cost-effectiveness thresholds and health care decision-making. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(2):175–80.

Byford S, Raftery J. Perspectives in economic evaluation. BMJ. 1998;316(7143):1529–30.

Brouwer WB, Culyer AJ, van Exel NJ, Rutten FF. Welfarism vs. extra-welfarism. J Health Econ. 2008;27(2):325–38.

Barton MB, Dawson R, Jacob S, Currow D, Stevens G, Morgan G. Palliative radiotherapy of bone metastases: an evaluation of outcome measures. J Eval Clin Pract. 2001;7(1):47–64.

Krol M, Papenburg J, Koopmanschap M, Brouwer W. Do productivity costs matter?: the impact of including productivity costs on the incremental costs of interventions targeted at depressive disorders. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(7):601–19.

Tranmer JE, Guerriere DN, Ungar WJ, Coyte PC. Valuing patient and caregiver time: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(5):449–59.

Kigozi J, Jowett S, Lewis M, Barton P, Coast J. Estimating productivity costs using the friction cost approach in practice: a systematic review. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17(1):31–44.

Krol M, Brouwer W, Rutten F. Productivity costs in economic evaluations: past, present, future. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(7):537–49.

Krol M, Brouwer W. How to estimate productivity costs in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(4):335–44.

Krol M, Brouwer WB, Severens JL, Kaper J, Evers SM. Productivity cost calculations in health economic evaluations: correcting for compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(11):1981–8.

Nicholson S, Pauly MV, Polsky D, Sharda C, Szrek H, Berger ML. Measuring the effects of work loss on productivity with team production. Health Econ. 2006;15(2):111–23.

Steel J, Godderis L, Luyten J. Productivity estimation in economic evaluations of occupational health and safety interventions: a systematic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2018;44(5):458–74.

Brouwer W, Huls S, Sajjad A, Kanters T, Roijen LH, van Exel J. Absence of absenteeism: some thoughts on productivity costs in economic evaluations in a post-corona era. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022;40(1):7–11.

Krol M, Brouwer W. Unpaid work in health economic evaluations. Soc Sci Med. 2015;144:127–37.

Brouwer WB, Koopmanschap MA. The friction-cost method : replacement for nothing and leisure for free? Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(2):105–11.

Birnbaum H. Friction-cost method as an alternative to the human-capital approach in calculating indirect costs. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(2):103–4.

Johannesson M, Karlsson G. The friction cost method: a comment. J Health Econ. 1997;16(2):249–55.

Pauly MV, Nicholson S, Xu J, Polsky D, Danzon PM, Murray JF, et al. A general model of the impact of absenteeism on employers and employees. Health Econ. 2002;11(3):221–31.

Koopmanschap M, Burdorf A, Jacob K, Meerding WJ, Brouwer W, Severens H. Measuring productivity changes in economic evaluation: setting the research agenda. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(1):47–54.

Knies S, Boonen A, Candel MJ, Evers SM, Severens JL. Compensation mechanisms for lost productivity: a comparison between four European countries. Value Health. 2013;16(5):740–4.

Severens JL, Laheij RJ, Jansen JB, Van der Lisdonk EH, Verbeek AL. Estimating the cost of lost productivity in dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12(9):919–23.

WBF Brouwer KV, R Hoefman, J van Exel. Production losses due to absenteeism and presenteeism: The influence of compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects. PharmacoEconomics.

Cunningham SJ. Economic evaluation of healthcare–is it important to us? Br Dent J. 2000;188(5):250–4.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000100.

Brouwer WB, van Exel NJ, Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FF. Productivity costs before and after absence from work: as important as common? Health Policy. 2002;61(2):173–87.

Zhang W, Bansback N, Anis AH. Measuring and valuing productivity loss due to poor health: a critical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(2):185–92.

Zhang W, Bansback N, Boonen A, Severens JL, Anis AH. Development of a composite questionnaire, the valuation of lost productivity, to value productivity losses: application in rheumatoid arthritis. Value Health. 2012;15(1):46–54.

Jacob-Tacken KH, Koopmanschap MA, Meerding WJ, Severens JL. Correcting for compensating mechanisms related to productivity costs in economic evaluations of health care programmes. Health Econ. 2005;14(5):435–43.

Koopmanschap MA. PRODISQ: a modular questionnaire on productivity and disease for economic evaluation studies. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2005;5(1):23–8.

Hanly P, Maguire R, Drummond F, Sharp L. Variation in the methodological approach to productivity cost valuation: the case of prostate cancer. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(9):1399–408.

Zhang W, Sun H, Woodcock S, Anis A. Illness related wage and productivity losses: Valuing “presenteeism.” Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:62–71.

Lensberg BR, Drummond MF, Danchenko N, Despiégel N, François C. Challenges in measuring and valuing productivity costs, and their relevance in mood disorders. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:565–73.

Tessier P, Sultan-Taïeb H, Barnay T. Worker replacement and cost-benefit analysis of life-saving health care programs, a precautionary note. Health Econ Policy Law. 2014;9(2):215–29.

Rost KM, Meng H, Xu S. Work productivity loss from depression: evidence from an employer survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:597.

Pauly MV, Nicholson S, Polsky D, Berger ML, Sharda C. Valuing reductions in on-the-job illness: “presenteeism” from managerial and economic perspectives. Health Econ. 2008;17(4):469–85.

Drummond MF, Jefferson TO. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. The BMJ Economic Evaluation Working Party. BMJ. 1996;313(7052):275–83.

Lo Sasso AT, Rost K, Beck A. Modeling the impact of enhanced depression treatment on workplace functioning and costs: a cost-benefit approach. Med Care. 2006;44(4):352–8.

Søgaard R, Sørensen J, Linde L, Hetland ML. The significance of presenteeism for the value of lost production: the case of rheumatoid arthritis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;2:105–12.

Strömberg C, Aboagye E, Hagberg J, Bergström G, Lohela-Karlsson M. Estimating the effect and economic impact of absenteeism, presenteeism, and work environment-related problems on reductions in productivity from a managerial perspective. Value Health. 2017;20(8):1058–64.

Arcidiacono P, Kinsler J, Price J. Productivity Spillovers in Team Production: evidence from Professional Basketball. J Law Econ. 2017;35(1):191–225.

Sedatole KL, Swaney AM, Woods A. The implicit incentive effects of horizontal monitoring and team member dependence on individual performance. Contemp Account Res. 2016;33(3):889–919.

Bouwmans C, Krol M, Severens H, Koopmanschap M, Brouwer W, Hakkaart-van RL. The iMTA productivity cost questionnaire: a standardized instrument for measuring and valuing health-related productivity losses. Value Health. 2015;18(6):753–8.

Rees DI, Zax JS, Herries J. Interdependence in worker productivity. J Appl Economet. 2003;18(5):585–604.

Chiu K, MacEwan JP, May SG, Bognar K, Peneva D, Zhao LM, et al. Estimating productivity loss from breast and non-small-cell lung cancer among working-age patients and unpaid caregivers: a survey study using the multiplier method. MDM Policy Pract. 2022;7(2):23814683221113850.

Keita Fakeye MB, Samuel LJ, Drabo EF, Bandeen-Roche K, Wolff JL. Caregiving-related work productivity loss among employed family and other unpaid caregivers of older adults. Value Health. 2023;26(5):712–20.

Hubens K, Krol M, Coast J, Drummond MF, Brouwer WBF, Uyl-de Groot CA, Hakkaart-van Roijen L. Measurement instruments of productivity loss of paid and unpaid work: a systematic review and assessment of suitability for health economic evaluations from a societal perspective. Value Health. 2021;24(11):1686–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2021.05.002.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Wichor Bramer for his help with designing the search strategy, and we would like to thank Kimberley Hubens, MSc. for her contributions in selecting eligible studies, titles, and abstracts for the full-text reading.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Author contributions

MK: Conducted and updated the systematic literature review alongside author 4 in the capacity of independent reviewer, including study selection, assessment of methodological quality, and data extraction; updated the manuscript and contributed critical revisions to the paper, including the update of the systematic literature review; drafted the manuscript and revised it based on editor and reviewer comments; approved the final manuscript version to be published. NH: Conceived and designed the systematic literature review protocol (objective, research question, PICO, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and methodology); conducted the first draft of the systematic review, including the search strategy, study selection, assessment of methodological quality, data extraction, first analysis, synthesis, and presentation; assisted in revising the manuscript prior to resubmission; approved the final manuscript version to be published. WB: Provided substantial intellectual contributions to the update of the systematic literature review; provided critical revisions to the background, result interpretation, discussion, and relevance/conclusion of the manuscript; contributed to addressing reviewer comments and provided input to revised the manuscript prior to resubmission; approved the final manuscript version to be published. LH: Established the research question and research design; conducted and updated the systematic literature review alongside author 1 in the capacity of independent reviewer; updated the manuscript and provided critical revisions to the manuscript; provided critical revisions to the full manuscript, ensuring overall accuracy, consistency, and rigor; addressed and processed reviewer comments and provided input to revised the manuscript prior to resubmission; approved the final manuscript version to be published.

Funding

The research team received no external funding for this study.

Conflict of interest

MK, NH, WB, and LH declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data availability

The papers were collected using PubMed and EconLit databases. The search string and period is included in the paper.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krol, M., Hosseinnia, N., Brouwer, W. et al. Multiplier Effects and Compensation Mechanisms for Inclusion in Health Economic Evaluation: A Systematic Review. PharmacoEconomics 41, 1031–1050 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-023-01304-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-023-01304-4