Abstract

Background

The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire is used to measure treatment effects on the quality of life. For cost-utility analyses, EQ-5D-5L profiles are assigned numbers representing societal preferences (index weights). On the cost side, the indirect costs are frequently included: the value of product lost due to illness-related absences (absenteeism) or diminished productivity (presenteeism). The possibility to use EQ-5D data to estimate absenteeism and presenteeism (A&P) would be useful, if real-world data on A&P are lacking. However, beyond-health factors may also matter for A&P.

Objective

We aimed to assess how A&P depend on the EQ-5D-5L profile, while accounting for job characteristics (e.g. remote or in-office).

Methods

We surveyed 756 employed Poles. Respondents reported their job characteristics and evaluated the impact of eight hypothetical EQ-5D-5L profiles on A&P (two blocks of states used). Econometric modelling was used to establish the determinants of A&P.

Results

Both A&P increase with health problems as indicated across EQ-5D-5L dimensions (especially mobility and self-care), and this impact differs from the impact on index weight (e.g. pain/discomfort barely impact the A&P). The job characteristics mattered: absenteeism decreases in sedentary occupations and increases in those occupations performed remotely or requiring cooperation, while presenteeism increases in jobs performed remotely and decreases for those requiring creative thinking.

Conclusions

The entire EQ-5D-5L profile, not just index weights, should be used to estimate A&P. That job characteristics matter may be relevant in applications, as some diseases concentrate in specific subgroups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

EQ-5D-5L data may be used to approximate absenteeism and presenteeism (A&P) in cost-utility or cost-of-illness studies, if real-world data on A&P are lacking. |

How EQ-5D-5L dimensions impact A&P and index weight differs: A&P are affected by mobility and self-care issues more than by pain and discomfort. |

Job characteristics also impact A&P, which may be relevant in decisions regarding specific patient subgroups. |

1 Introduction

To decide whether a health technology should be reimbursed, several factors are taken into account. For instance, in a cost-utility analysis (CUA), the cost of the technology is juxtaposed with the health outcomes, usually defined as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) [10]. To evaluate the quality of life component, one of the EQ-5D family of instruments is often used [18, 34]. In these instruments, a health state is defined using five dimensions: mobility (MO), self-care (SC), usual activities (UA), pain/discomfort (PD) and anxiety/depression (AD). In the EQ-5D-5L instrument, each dimension is assigned a 1–5 level expressing the intensity of the problems (1 denoting no problems, 5 referring to severe problems), jointly defining an EQ-5D-5L health profile (health state). EQ-5D-5L profiles can be assigned numbers (also known as index weights, collected in value sets) expressing how good or bad they are as perceived by a given society to subsequently be used to define QALYs (see, e.g. [1, 7, 11, 25], for examples of EQ-5D-5L value sets).

For CUA credibility, it is just as essential to properly measure the costs of a given treatment technology. Which elements should be included (e.g. if only public expenses or also patients co-payments) depends on the selected perspective [28]. In many countries, the broadest societal perspective is either preferred (e.g. in Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden) or indicated as a possible addition to the public payer perspective (e.g. in Estonia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Spain) [35]. From the societal perspective, the value of the goods and services rendered unavailable to society because of illness should also be calculated, which are referred to as indirect costs [8]. In a recent review, the productivity costs were found to be used in 12% of CUAs using QALYs [19]. Indirect cost consists of two parts: (1) absenteeism, i.e. the results of an employee being away from work because of illness or (2) presenteeism, i.e. the result of an employee being present but being less productive because of illness. Therefore, in order to perform a CUA from a societal perspective, understanding the impact of health technology on absenteeism and presenteeism (A&P) is vital.

There are many data sets on health-related quality of life in general (using EQ-5D in particular) for a wide range of health conditions and health technologies. Hence, being able to estimate A&P based on EQ-5D health profiles would be useful. Additionally, because EQ-5D data are often used in existing CUA models, expanding the models to also account for the quality-of-life impact on A&P is feasible. It is worth noticing that indirect cost is also often estimated beyond CUAs: in cost-of-illness or burden-of-disease studies, when the economic consequences of a health condition is studied overall, not in a context of a specific health technology [4, 15]. In such studies, cost of illness is evaluated and it reflects the economic burden that illness imposes on the society, including the direct, indirect and intangible dimensions.

Admittedly, if real-world evidence on the impact of illness on the professional activity is available for a health condition and a specific country in question, such data should be preferred (for an example of such data, see [2]). However, in many situations such data are either missing entirely or they do not contain all the relevant information. For instance, the study referenced here analyses the taxed income changes, and—in consequence—may not reflect the presenteeism fully. In such cases, being able to use EQ-5D data as a proxy could be useful to fill in the gaps.

Krol et al. [22] showed that EQ-5D-3L health states provide reasonable predictions of A&P. However, the authors themselves point out as a limitation that the results are based on the respondents of different professions. Jobs with certain characteristics may be particularly vulnerable or robust to certain types of health problems. For instance, one may hypothesise that problems with mobility may reduce employee absenteeism less, if working remotely is possible (which is clearly more common in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic), while physical pain may reduce the productivity of a construction worker more than that of a lawyer [3, 23]. Therefore, the estimated models linking EQ-5D and A&P may be less accurate when applied to specific homogeneous groups of patients. So far, no systematic studies have been conducted to jointly estimate the impact of health problems and job characteristics on indirect costs.

We aimed to assess how health problems, as measured using EQ-5D-5L, are associated with A&P, while also taking into account the following job characteristics: possibility to work remotely; proportion of time spent in a sedentary position; time devoted to creative thinking; requirement to work with other people; physical strength. To this end, we conducted a survey in which 756 working Poles (sampled to match the distribution of sex, age and area of residence among the general population) evaluated eight hypothetical EQ-5D-5L health states in the context of their own job characteristics. Econometric modelling was used in order to measure the impact on A&P.

We see two types of contribution arising from our paper. The first one concerns the impact of EQ-5D dimensions on A&P. Using EQ-5D-5L (in contrast to [22] who used the 3L version) offers the ability to verify earlier results with this finer-grained instrument (for instance, see [14] for a comparison of the sensitivity of 3L and 5L in measuring health problems). Comparing the impact of EQ-5D dimensions on A&P with their impact on value sets can show to what extent the index weights can be used to approximate indirect costs (see also [24] for a discussion on why QALYs cannot incorporate indirect costs).

Second, we show explicitly how various job characteristics, along with health problems, are associated with A&P. Admittedly, the type of occupation should not differentiate the access to healthcare. Nevertheless, information concerning such an impact may be useful when a CUA is performed for an illness that is characteristic for certain social groups, as defined by characteristics also associated with the occupation type (e.g. defined by age, sex or education). For instance, testicular cancer is diagnosed mainly in men aged 15–40 years [5], while obesity-related health issues in high-income countries are more common in less educated people [6, 26]. If less educated people are more likely to perform non-remote jobs requiring physical strength and a lack of creative thinking, the relationship between the EQ-5D health problems and A&P may be different than in the general population.

Our paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we describe the methods used in the study, including the description of the data collection process and the econometric approach employed. In Sect. 3, we present the raw results of the survey and the results of the modelling. In Sect. 4, we discuss the findings and limitations of the study. We set out brief conclusions in Sect. 5.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Collection and Sample

We used data collected in a survey in Poland during 11–16 June, 2021 by Kantar SA, a professional research company [16]. There were 756 working respondents surveyed using a Computer Assisted Personal Interview technique. Most of the questionnaires (555) were collected as a part of a wider study (Omnibus Survey) conducted by Kantar SA on a regular basis, and respondents also answered other questions, before and after our questionnaire. The remaining questionnaires were collected during a separate survey, specifically for the present project.

The sample selection process ensured that the structure of the initial sample with respect to sex, age, place of residence or region resembled the overall population of Poland aged 15 years or more. Each interview lasted for about 15 minutes. Respondents received no payment for their participation in the survey. A detailed description of the sample selection process is included in Section A.1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM).

2.2 Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of two parts. In the first part, respondents answered basic demographic questions about their age, sex and level of education (for possible answers to this and other questions, see Table 1). The respondents were also asked about their job characteristics: whether it is performed remotely; the proportion of time spent in a sedentary position; whether it requires physical strength; whether it requires collaboration with others (e.g. with co-workers, clients, contractors); and whether it involves creative thinking.

In the second part, the respondents were asked to consider eight hypothetical health states defined using EQ-5D-5L, and for each of those to envision whether they would be able to work in that circumstance, i.e. they were asked about their predicted absenteeism (yes/no) and presenteeism (on a 0–10 scale, where 0 denotes no impact and 10 denotes total inability to carry out work). The selection of a scale for presenteeism was meant to provide consistency with the widely used Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire [32].

The health states were selected in the following manner. To balance the number of observations per state, the number of distinct states evaluated and the required time per respondent, we used two blocks of eight states each (i.e. 16 states in total). Overall, we used four mild states (with a level sum score (LSS)—sum of the levels across all health dimensions—\({\text {LSS}}\le 7\)), ten moderate states (\(8\le {\text {LSS}}\le 16\) ) and two severe states (\({\text {LSS}}\ge 17\)), split evenly between blocks (i.e. \(2+5+1=8\)). In our design, we focused on moderate states and did not include level 5 in any dimension, because on the one hand, the overall number of mild states is lower in the descriptive system, and on the other hand, we expect that respondents in severe states are likely to be unable to work (hence, such states would provide little information on presenteeism).

The specific blocks were as follows:

-

block I: (mild) 11121, 11212, (moderate) 13122, 14113, 11414, 42321, 21334, (severe) 34244,

-

block II: (mild) 11122, 21112, (moderate) 11421, 13313, 13224, 32314, 34232, (severe) 24443.

The detailed description of the selection of health states is included in Section A.2 of the ESM.

2.3 Data Analysis

There were no missing values in the dataset. We decided to use all of the collected data, i.e. we did not want to alter the properties of the sample obtained (given its resemblance to the Polish population of people aged 15 years or more), so we did not remove data based on any quality checks.

The data analysis consists of three distinct parts: (1) descriptive demographics and job characteristics analysis, (2) studying the impact of EQ-5D-5L dimensions on A&P and (3) examining the impact of job characteristics on A&P.

2.3.1 Descriptive Demographics and Job Characteristics

Regarding the first type of analysis, we present the distribution of an individual’s job characteristics. For the sake of a subsequent econometric analysis (to detect possible collinearity issues), we studied the correlations (Spearman’s rank) between the individual characteristics and between these characteristics and A&P.

2.3.2 Impact of EQ-5D-5L Dimensions on A&P

Regarding the second part of the analysis, we checked how A&P depend on the type and gravity of health problems in hypothetical health states. Owing to the presence of only a limited number of distinct health states in the design, it was challenging to credibly estimate the impact of individual levels for individual dimensions (four levels of five dimensions were used in the design, which leads to \(1+3\times 5\) parameters to be estimated—i.e. an intercept and three levels of five health dimensions, as level 1 was used as a reference point and level 5 was not used in the design). Because the steps between consecutive levels do not need be perceived equally by the respondents, one should not simply use the level values as continuous variables. Instead, we used two simplifying approaches to reduce the number of parameters to be estimated. The first approach consisted of summarising the information on the health state with the estimated health state index weight (as calculated by [11]), either for the whole health state or decomposing the disutility (i.e. the difference of index weight from full health) between the five dimensions. We started with showing how the overall health state index weight correlates with A&P, using a generalised logistic function to quantify the link [33].

We then proceeded to measure the impact of individual dimensions, with each dimension measured using a single number, i.e. the utility loss attributed to this specific dimension. Such an approach allowed for a reduction in the number of parameters to five (relative importance of dimensions), while acknowledging for non-equal steps between levels. In this approach, the relative importance of levels for each dimension in their impact on A&P was assumed to be identical to their impact on index weight (which is relaxed in the second approach below), and we focused on measuring whether the relative importance of individual dimensions differs from their importance in calculating the index weight (health issues important for the satisfaction of life may differ from health issues that compromise the ability to work). Separate econometric models were built for A&P. Absenteeism was modelled as a binary variable using a linear mixed-effect model with random intercepts at the level of the respondent, and presenteeism was modelled with an analogous model with a continuous response variable.

In another simplifying approach, inspired by [31], we used multiplicative models with random intercepts at the level of the respondent, in each of these (separately for A&P) two sets of parameters are considered: those measuring the importance of dimensions and those measuring the relative importance of levels (assumed to be identical across the dimensions). Consequently, the number of parameters to be estimated reduces to \(8=1+5+2\) (including the intercept, and acknowledging the fact that no level 5 is present in our study). Specifically, the following model was estimated for absenteeism:

where:

A stands for absenteeism, the \(\alpha\) terms are the parameters to be estimated (\(\alpha _0\) is an intercept, \(\alpha _\mathrm{MO},\mathrm{etc.},\) represent the importance of the corresponding dimensions, and \(\alpha _{L2}\) and \(\alpha _{L3}\) represent the relative importance of the levels relative to the maximal level 4 in the design), \(\mathrm{MO}2\), etc. are the dummy variables indicating whether a given dimension is on a given level, and \(\varepsilon\) is the error term. For presenteeism, no link function was used and the \(P=X\) model was estimated (P stands for presenteeism, and X is defined as in Eq. 1).

2.3.3 Impact of Job Characteristics on A&P

In the third part of the analysis, we measured the impact of job characteristics on A&P. To visualise the data and assess their face validity, we first presented the mean A&P (separately) for individual health states and levels of job characteristics. We then proceeded with econometric modelling (both with a linear and non-linear approach) with variables describing the job characteristics. These variables were treated as continuous values from 1 to 5, where 1 referred to none or hardly any time, and 5 referred to entirely or almost entirely; in the case of remote work, the values 1, 3 and 5 were used, in order to equalise the range of values and make the comparison of coefficients between the variables easier.

In each model (also in non-linear models), the non-significant variables were removed using backward selection and the significance threshold of 0.05. For linear models, we checked for collinearity using the variance inflation factor (\({\text {VIF}}<10\) treated as no collinearity). If the collinearity was present, the variable with the highest ariance inflation factor was discarded. For each model (both linear and non-linear), we present the value of the root mean square error (RMSE). For linear models, we also present Nakagawa’s \(R^2\) [27]. In this paper (and in the ESM), we only present the final models. All the analyses were conducted in R, version 4.0.3 [30].

In the ESM, we present additional models, for instance, models with job characteristics treated as ordinal variables coded with incremental dummies.

3 Results

3.1 Basic Descriptive Statistics

The questionnaire was completed by 756 respondents, 52% male, with a mean age of 42.95 (\({\text {min}} = 19\), \({\text {max}} = 76\), standard deviation \({\text {SD}} = 12.2\)). Both age and sex distributions in the sample resemble those in the general population of working Poles [9]—in 2022, in the working population of Poles, the share of male individuals was equal to 55% and the weighted mean age (weighted as it was calculated from age groups) was equal to 41 years. Other demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. As one can see, in most of the job characteristics, the level values were conveniently spread across the possible values.

As expected, the strongest correlation (in absolute terms) prevailed between the time spent in a sedentary position and the share of time spent on activities requiring physical strength (Spearman correlation of \(-0.67\), for details see Table B.1 of the ESM). To avoid collinearity, we only used one of these two variables in the modelling. As presenteeism was more correlated with physical strength, and absenteeism was more correlated with a sedentary position, in models with absenteeism as the outcome variable we use the variable referring to the sedentary position, whereas in models with presenteeism as the outcome variable we use the variable referring to physical strength.

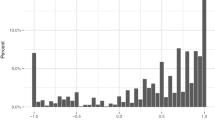

In Table 2, we summarise the impact of each health state on A&P. As one can see, both A&P increase with the severity of health state. This is also confirmed in Fig. 1, where we show the relationship between the health state disutility and A&P by using a generalised logistic function fitted to the data. For mild and moderate health states, the relationship between the health state disutility and A&P seems linear, and its slope decreases for more severe health states.

3.2 Health-Related Determinants of A&P in Hypothetical Health States

To check the face validity of values of A&P obtained from the respondents, we show how the mean A&P depend on the level value split per individual EQ-5D-5L dimensions (irrespective of the remaining dimensions, i.e. pooling all health states), see Fig. B.1 of the ESM. Overall, for higher levels, higher mean A&P were observed. However, there were non-monotonicities present, which further motivates using the simplifying approaches outlined in Sect. 2 in view of the limited number of health states in the design. Nonetheless, in Section B.3 of the ESM, we present the results of the model for A&P using the individual levels of all health dimensions, for completeness. The results indicate that severe problems in the self-care activities dimension had the highest impact on absenteeism. In the case of presenteeism, the highest impact had dimension SC on level 3 or higher. However, some of the results were counterintuitive: higher levels of health states were not always characterised by higher (in absolute terms) coefficients of the models.

In Table 3, we present the results of models explaining A&P by the utility loss of each dimension. Surprisingly, PD was not significant in either model. Other dimensions are associated with A&P in an intuitive way (i.e. greater disutility increases A&P). The smaller coefficient for AD (than for MO, SC or UA) shows that the impact of this dimension on A&P is relatively smaller than on the utility. The relative ranking of dimensions is identical for A&P (SC>MO>UA>AD>non-significant PD). Absenteeism can be explained more precisely with the available variables than presenteeism can, i.e. the proportion of explained variance is larger.

In the case of presenteeism, the intercept in the model can be interpreted as a non-linearity of the influence of the utility loss on health dimensions in the following way. As the value of the intercept is relatively high, any initial deterioration of health causes an increase in the presenteeism by the summed value of the intercept and the coefficient for the dimension that was deteriorated. A subsequent deterioration of health causes increased presenteeism only according to the value of the coefficient. In economic parlance, the dimensions are complements in terms of them allowing for workers to be productive, as the deterioration of the first dimension has a greater negative effect than the deterioration of the second.

In Table 4, we present the results of the non-linear multiplicative model explaining A&P (Eq. 1). In this approach, all dimensions have a significant impact on A&P. The overall relative importance pattern is similar: PD has a marginal impact, and the first three dimensions (MO, SC, UA) have the largest impact. The RMSE was lower than for the linear model, particularly in the case of the model for absenteeism.

For absenteeism, the importance of level 2 to level 4 equals 0.40, and that of level 3 to level 4 equals 0.57. In the case of presenteeism, the relative importance of level 2 to level 4 equals 0.41, and of level 3 to level 4 equals 0.72. In the Polish value set [11], the importance of level 2 to level 4 is equal to 0.20, 0.28, 0.24, 0.11 and 0.17, and the importance of level 3 to level 4 is equal to 0.27, 0.42, 0.41, 0.19 and 0.27, respectively, for dimensions MO, SC, UA, PD and AD. This means that the relative influence of small levels on A&P is greater than on disutility.

3.3 Acknowledging for Job Characteristics

In Fig. 2, we present the impact of various job characteristics on average A&P, divided according to individual states, to demonstrate how consistent the impact of the two elements (state severity measured with its disutility and various levels of individual job characteristics) was in a set of such two-factor analyses.

On average, mean A&P consistently increased with the state severity (as measured by the disutility), which confirms the results presented in the previous subsection. The impact of job characteristics (i.e. the slopes of the lines in Fig. 2), however, is much less visually pronounced, and the direction differs between the characteristics. For instance, increased time spent on creative thinking seems to be associated with lower A&P (part (a)), while the remote character of the work seems to have the opposite direction (Fig. 2 part (d)).

In Table 5, we present the results of the econometric analysis (only statistically significant variables). Most of the variables defining the job characteristics are statistically significant (remote type of work, time spent in sedentary position and work with people in the case of absenteeism; creative thinking and remote type of work in the case of presenteeism). The variables describing occupation type increased the model’s fit in the case of absenteeism. The values of RMSE were the same as for the model only with respect to the variables referring to disutility of health dimensions.

Working in a sedentary position is associated with lower absenteeism, and using creative thinking is associated with lower presenteeism, for a given health state. Working remotely is characterised by higher A&P. Respondents who were working with other people had higher absenteeism, while this characteristic is not associated with presenteeism. Furthermore, using creative thinking is not associated with absenteeism. Presenteeism is higher for respondents who had activities requiring physical strength.

Table 6 presents the results of the non-linear multiplicative model (Eq. 1) explaining A&P extended by the job characteristics (significant characteristics). The RMSEs of these models were the same as in the case of non-linear models only containing variables referring to health dimensions. In such an approach, two characteristics remain significant for absenteeism: remote type of work (which is associated with higher absenteeism) and working in a sedentary position (which is associated with lower absenteeism), while two characteristics remain significant for presenteeism: remote type of work (which is associated with higher presenteeism) and the requirement for creative thinking (which is associated with lower presenteeism).

In Table C.1 in the ESM, we present the results of a more simplified model, where the disutility is not split per individual dimension (with no substantial change for the results). Alternatively, in Table C.2 of the ESM, we present a less parsimonious model with more parameters, i.e. looking into the impact of individual levels of the job characteristics with incremental dummies. Models with interactions between health dimensions and job characteristics were tried, yet no significant interactions were found.

4 Discussion

In the paper, we showed how health problems defined with an EQ-5D-5L descriptive system along various job characteristics impact on employee productivity, categorised according to A&P. The results agreed with the motivation behind the study: various types of jobs differ with respect to how health impacts productivity, and the impact of health on productivity is different than the impact on a health state’s utility. We believe that the results of our study can be useful when no real-world data on A&P are available.

4.1 Results

Looking at the impact of dimensions on A&P, we clearly see two groups of dimensions. While MO, SC and UA have a substantial impact on both A&P, the impacts of PD and AD are much lower (and even insignificant for the former dimension in some model specifications).

Particularly in the case of presenteeism, we can see differences between the impact of dimensions on level 3 and level 2 that are higher than in the Polish value set, i.e. changes in the levels of health dimensions cause greater changes in A&P than in the case of disutility.

Regarding the high-impact dimensions, as most of the respondents (79%) did not work remotely despite the pandemic, the high impacts of MO, SC and UA are rather intuitive. Problems with MO or SC can hinder people from getting ready for work or getting to work. The UA dimension, as presented in the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, is in fact defined in terms of being able to work (i.e. being able to work is presented in the descriptive system as one of the examples for how UA should be understood by respondents).

Regarding the low-impact dimensions, it is interesting to observe how PD correlates poorly with A&P while having the highest impact of all dimensions on health state utility in Poland [11]. Our results also contrast with [17], who show that chronic pain was significantly associated with reduced performance at work, i.e. presenteeism (albeit with no impact on absenteeism). We do not think our findings are counterintuitive, as one may imagine working while in pain. According to the Global Burden of Disease data from the Institute for Health Metric and Evaluation [13], in Poland in 2019, 16% of the population population aged above 20 years, 13% of those aged 35–39 years, 16% of those aged 40–44 years and 17% of those aged 45–46 years experienced lower back pain. This may indicate that some of the respondents experienced some amount of pain and assumed they could deal with it. Perhaps some respondents misunderstand the gist of the thought experiment and assumed they would be able to alleviate pain using pain killers. Clearly, the impact of pain on A&P would benefit from further research.

Our results regarding the ordering of dimensions (MO, SC, UA> PD and AD) partially agree with those of [22], who showed the following ordering of dimension importance (on the third level in EQ-5D-3L): MO>UA>PD>SC>AD (for absenteeism) and MO>PD>UA>AD>SC (for presenteeism). The high impact of MO is shared between their findings and ours, whereas the higher estimated impact of PD represents a clear difference. This difference might result from the fact that we excluded the most severe health states (i.e. level 5) from the design, while the worst level (3 in EQ-5D-3L) was present in [22].

Regardless of the above differences, our results clearly show that the impact of the health dimensions on utility differs from the impact on productivity, which implies that for an indirect cost estimation based on EQ-5D-5L data, the entire health profiles should be analysed comprehensively, not just summarised according to the index weight. However, when only the index weight is available, then the non-linearity in the association between the disutility and productivity (i.e. the diminishing marginal impact of disutility) should be accounted for. As shown in Fig. 1, for mild health states a small change in severity has a relatively larger impact on A&P, while beyond a certain threshold this impact declines. As our data set did not contain very severe states, we are unable to determine if the concavity holds for the entire range.

The job characteristics vary in their impact on A&P, and we believe that the obtained associations are intuitive. People who spent most of their work time on creative thinking were less likely to be absent and were more productive at work. Such results provide interesting conclusions, as people who perceive themselves as using creative thinking often occupy high positions and their productivity at work can be crucial for a firm’s functioning.

A positive correlation between the proportion of time spent on activities requiring physical strength and both A&P, and a negative relationship between the proportion of time spent in a sedentary position and A&P was in line with our expectations, as a sedentary position precludes using physical strength.

People who spent more time working with other people had higher absenteeism. Depending on the nature of this cooperation, this may constitute either good or bad news for the indirect cost. If the cooperation is of a complimentary type (which we think is more likely), then one person’s absence affects the whole team’s output, which in consequence increases the indirect cost. If the cooperation is more related to one person being able to substitute for the other (firm’s functioning is based on team work), then the indirect costs of illness are substantially higher [29].

The impact of the variable referring to a remote type of work was not in line with our expectations: working remotely was associated with higher A&P, even though one might expect that working from home also makes it possible to be working when, for instance, facing problems related to mobility. Furthermore, we expected that a remote type of work would have no impact on presenteeism, as it is more related to the ability to perform duties. We find it difficult to provide a convincing intuition behind our findings, and further work related to this issue is recommended.

4.2 Data

In our paper, we used data from a survey among professionally active Poles. Conveniently, in Poland, there is a single obligatory public healthcare system. In consequence, the social safety net is equal for all workers, which makes our sample more homogeneous. In consequence, the estimated A&P do not depend on the access to healthcare.

However, the fact that how health conditions impact A&P may depend on the healthcare system means that our results may not be directly transferred to other countries that have different legal regulations or economic realities. Generalising the results to other countries can also be difficult for culturally distant countries, as there can be a different understanding of the EQ-5D levels and dimensions.

Our survey was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though the survey was carried out in June 2021, when the number of active cases was relatively low in Poland, the pandemic had already changed the labour market significantly. The functioning of certain branches of the economy was curtailed (e.g. restaurants, hotels, tourism), and many people were working remotely than prior to the pandemic. We also have to acknowledge that the respondents’ state of mind, thinking about health problems and predicting the impact of health on work might have been rather special factors pertaining to these times. Nevertheless, because the COVID pandemic is clearly not entirely in the past, we would claim that our data are rather compatible with how the labour market functions currently, in contrast to the data used in [22], for instance.

4.3 Limitations

The major limitation of the study is that results refer to hypothetical health states, not their own actual health state. However, as in the general population we observe a limited number of health states, such an approach is often used in EQ-5D studies [see, e.g. 11].

Another significant limitation of our study is the number of evaluated health states. In our study, we use information on 16 EQ-5D-5L health states. The number of evaluated health states resulted from the length of the questionnaire and the fact that it was collected via a Computer Assisted Personal Interview. The study conducted by [21] used information on 96 EQ-5D-3L health states and data were collected from a self-completion survey. Although using health states defined with EQ-5D-3L would mean having information about a greater percentage of health states, we decided to use the 5L version of EQ-5D because, according to [14] 5L is more sensitive and precise than 3L, and the 3L version has a tendency to overestimate health problems. In addition, we preferred to gather information during a Computer Assisted Personal Interview, as we anticipated that a survey conducted by an interviewer should provide a better quality of data (the interviewer controls the time spent on the survey, as well as being able to answer any questions asked by respondents).

In our study, we did not include health dimensions on level 5 as we expected people to be less likely to work in such health states and we would collect no information on presenteeism. Therefore, such health states were not used in view of sample size and duration limit constraints. However, the lack of level 5 is not a significant limitation in view of two observations. First, in some model specifications, we used disutilities as explanatory variables. Hence, the lack of level 5 only reduces the range of disutility considered. Second, the marginal effect of the disutility is diminishing, i.e. A&P are relatively strongly affected by low levels.

We only collected data on the occupation characteristics, and not on the specific occupation. This makes it impossible to verify if other factors influence A&P. Such an approach was used as we decided that jobs with similar names may still require different activities between companies, and a specific list of characteristics will be more accurate. Admittedly, the selection of occupation characteristics was arbitrary and did not include, for instance, information on if the job requires low or high skills.

Another limitation of the present study is the fact that respondents were not paid for their participation in the survey. We believe that paying respondents could enhance their motivation. However, this could also mean that the survey is completed carelessly, as the respondent may be more concerned with the compensation itself. In the study presented by [22], respondents were given money for a donation to a charity of their choosing, in addition to being entered into a prize draw.

Most of the questionnaires were collected as part of a larger questionnaire (Omnibus survey). Our questionnaire was used in the middle of an interview that was 45 minutes in duration. The length of the whole questionnaire could negatively influence the quality of collected data and—as [12] show—extensive questionnaires can result in similar answers between questions.

As we mentioned above, one might consider the unknown impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our results as a limitation. As the pandemic caused substantial changes in the behaviour of many people (as access to many facilities was limited during the lockdown), there is a possibility that the meaning and interpretation of some dimensions changed, for example usual activities or mobility. Moreover, many Poles suffered directly from COVID-19 and its consequences, and might relate health problems only to this particular disease.

In our study, we evaluated A&P as a source of the indirect costs of illness. There is an ongoing discussion between the human capital approach and the friction cost method proponents [20, 21] as to how long the absenteeism cost should be calculated for (i.e. when the loss of a worker is compensated for, such as by new hires). However, the aspect of presenteeism depends less on this particular discussion, as the duties of a present but not yet fully effective worker are less likely to be compensated for at all.

5 Conclusions

The indirect cost of illness due to A&P depends on both the health state and the job characteristics. Severity seems to have a diminishing marginal impact on A&P. The impact of job characteristics differs between A&P, and—obviously—on the specific characteristic. The impact of some characteristics is comparable to the impact of individual EQ-5D-5L dimensions, demonstrating that the impact of an illness on the indirect cost may strongly vary between sub-populations. The impact of individual dimensions on A&P differs from the impact on disutility, which shows the need to analyse the health state data comprehensively, not simply via a summary index weight.

References

Andrade LF, Ludwig K, Goni JMR, Oppe M, de Pouvourville G. A French value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(4):413–25.

Blakely T, Sigglekow F, Irfan M, Mizdrak A, Dieleman J, Bablani L, Clarke P, Wilson N. Disease-related income and economic productivity loss in New Zealand: a longitudinal analysis of linked individual-level data. PLoS Med. 2021;18(11): e1003848.

Brouwer WB, Meerding WJ, Lamers LM, Severens JL. The relationship between productivity and health-related QOL. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(3):209–18.

Byford S, Torgerson DJ, Raftery J. Cost of illness studies. BMJ. 2000;320(7245):1335.

Chia VM, Quraishi SM, Devesa SS, Purdue MP, Cook MB, McGlynn KA. International trends in the incidence of testicular cancer, 1973–2002. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2010;19(5):1151–9.

Cohen AK, Rai M, Rehkopf DH, Abrams B. Educational attainment and obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013;14(12):989–1005.

Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, Mulhern B, van Hout B. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):7–22.

Ernst R. Indirect costs and cost-effectiveness analysis. Value Health. 2006;9(4):253–61.

Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Aktywność ekonomiczna ludności Polski—I kwartał 2022 roku, 2022. https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rynek-pracy/pracujacy-bezrobotni-bierni-zawodowo-wg-bael/aktywnosc-ekonomiczna-ludnosci-polski-i-kwartal-2022-roku,4,46.html.

Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996.

Golicki D, Jakubczyk M, Graczyk K, Niewada M. Valuation of EQ-5D-5L health states in Poland: the first EQ-VT-based study in Central and Eastern Europe. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(9):1165–76.

Herzog AR, Bachman JG. Effects of questionnaire length on response quality. Public Opin Q. 1981;45(4):549–59.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD compare. 2022. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

Janssen MF, Bonsel GJ, Luo N. Is EQ-5D-5L better than EQ-5D-3L? A head-to-head comparison of descriptive systems and value sets from seven countries. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(6):675–97.

Jo C. Cost-of-illness studies: concepts, scopes, and methods. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2014;20(4):327.

Kantar. 2021.https://www.kantar.com/.

Kawai K, Kawai AT, Wollan P, Yawn BP. Adverse impacts of chronic pain on health-related quality of life, work productivity, depression and anxiety in a community-based study. Fam Pract. 2017;34(6):656–61.

Kennedy-Martin M, Slaap B, Herdman M, van Reenen M, Kennedy-Martin T, Greiner W, Busschbach J, Boye KS. Which multi-attribute utility instruments are recommended for use in cost-utility analysis? A review of national health technology assessment (HTA) guidelines. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(8):1245–57.

Kim DD, Silver MC, Kunst N, Cohen JT, Ollendorf DA, Neumann PJ. Perspective and costing in cost-effectiveness analysis, 1974–2018. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(10):1135–45.

Koopmanschap MA, Van Ineveld BM. Towards a new approach for estimating indirect costs of disease. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(9):1005–10.

Krol M, Brouwer W, Rutten F. Productivity costs in economic evaluations: past, present, future. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(7):537–49.

Krol M, Stolk E, Brouwer W. Predicting productivity based on EQ-5D: an explorative study. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(5):465–75.

Lamers LM, Meerding WJ, Severens JL, Brouwer WB. The relationship between productivity and health-related quality of life: an empirical exploration in persons with low back pain. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):805–13.

Liljas B. How to calculate indirect costs in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;13(1):1–7.

Ludwig K, von der Schulenburg JMG, Greiner W. German value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(6):663–74.

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJ, Benyamin RM, Hirsch JA. Epidemiology of low back pain in adults. Neuromodul Technol Neural Interface. 2014;17:3–10.

Nakagawa S, Johnson PC, Schielzeth H. The coefficient of determination \({R}^2\) and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. J R Soc Interface. 2017;14(134):20170213.

Neumann PJ. Costing and perspective in published cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Care. 2009:S28–S32.

Pauly MV, Nicholson S, Xu J, Polsky D, Danzon PM, Murray JF, Berger ML. A general model of the impact of absenteeism on employers and employees. Health Econ. 2002;11(3):221–31.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. https://www.R-project.org/.

Rand-Hendriksen K, Ramos-Goñi JM, Augestad LA, Luo N. Less is more: cross-validation testing of simplified nonlinear regression model specifications for EQ-5D-5L health state values. Value Health. 2017;20(7):945–52.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–65.

Seber GA. Nonlinear regression models. In: The linear model and hypothesis. Berlin: Springer; 2015. p. 117–28.

The EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208.

van Lier LI, Bosmans JE, van Hout HP, Mokkink LB, van Den Hout WB, de Wit GA, Dirksen CD, Nies HL, Hertogh CM, van der Roest HG. Consensus-based cross-European recommendations for the identification, measurement and valuation of costs in health economic evaluations: a European Delphi study. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19(7):993–1008.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the EuroQol Research Foundation (EQ Project 91-2020RA). The opinions expressed by the authors in this publication do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the EuroQol Group or that of the EuroQol Research Foundation. We also thank Timothy Harrell for his assistance with editing the present paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was funded by the EuroQol Research Foundation (EQ Project 91-2020RA). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the EuroQol Research Foundation or the EuroQol Group.

Conflict of interest

Michał Jakubczyk is a member of the EuroQol Group. Beata Koń has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Availability of data and material

All data in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used for the statistical analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Author contributions

BK performed data analysis. Both authors contributed to the study conception, design and drafting of the manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koń, B., Jakubczyk, M. Measuring the Indirect Cost of Illness Using EQ-5D-5L While Accounting for Job Characteristics. PharmacoEconomics 41, 1051–1064 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-023-01267-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-023-01267-6