Abstract

Background and Objectives

EQ-5D-Y-3L health states are commonly valued by asking adults to complete stated preference tasks, ‘given their views about a 10-year-old child’ (hereafter referred to as proxy 1). The use of this perspective has been a source of debate. In this paper, we investigated an alternative proxy perspective: i.e. adults considered what they think a 10-year old-child would decide for itself (hereafter, proxy 2 (substitute)]. Our main objective was to explore how the outcomes, dispersion and response patterns of a composite time trade-off valuation differ between proxy 1 and proxy 2.

Methods

A team of four trained interviewers completed 402 composite time trade-off interviews following the EQ-5D-Y-3L protocol. Respondents were randomly allocated to value health states in either the proxy 1 or proxy 2 (substitute) perspective. Each respondent valued ten health states with the perspective they were assigned to, as well as one health state with the alternative perspective (33333).

Results

The use of different proxy perspectives yielded differences in EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation. For states in which children had considerable pain and were very worried, sad or unhappy, respondents’ valuations were lower in proxy 1 than in proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives, by about 0.2. Within-subject variation across health states was lower for proxy 2 (substitute) than proxy 1 perspectives. Analyses of response patterns suggest that data for proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives were less clustered.

Conclusions

There are systematic differences between composite time trade-off responses given by adults deciding for children and adults considering what children would want for themselves. In addition to warranting further qualitative exploration, such differences contribute to the ongoing normative discussion surrounding the source and perspective used for valuation of child and adolescent health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the valuation of EQ-5D-Y-3L, adults are asked to value health states for a 10-year-old child, but this change compared with the valuation of adult health states has been a source of ongoing discussion. |

In this study, we investigated an alternative perspective: i.e. adults considered what they think a 10-year-old child would decide for itself. |

We find systematic differences between composite time trade-off responses given by adults deciding for children and adults considering what children would want for themselves. |

1 Introduction

Children’s and adolescents’ health-related quality of life is increasingly measured with childhood-specific generic instruments such as CHU9D or EQ-5D-Y [1, 2]. These instruments comprise different dimensions and answering levels. For example, CHU9D measures health-related quality of life on nine dimensions that range from being able to do schoolwork to being able to join in on activities, and scores each of these with five levels [3, 4]. EQ-5D-Y, in contrast, consists of five dimensions [5, 6]: mobility, looking after myself, usual activities, pain/discomfort and being sad, and worried or unhappy. Although an extended five-level version is in development [7], in the currently available version of EQ-5D-Y-3L, respondents rate their own health by selecting one of three levels of severity for each dimension.

Childhood-specific generic instruments may be used to calculate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), the preferred outcome measure in cost-utility analyses [8]. Many national decision bodies (e.g. the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in the UK or the Zorginstituut in the Netherlands) recommend the use of EQ-5D instruments for this purpose [9], perhaps as a result of the many languages they are available in and their accompanying value sets [10]. Traditionally, these value sets have reflected the preferences of the adult general population, i.e. a representative sample of adults is asked to imagine living in and value health states described by the instruments (for an early example, see [11]). For EQ-5D-Y, this process of valuation is currently ongoing, with the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol released recently [12]. Earlier work [13] has shown that, owing to the different wording implemented in EQ-5D-Y, the use of adult value sets (e.g. EQ-5D-3L value sets) is not recommended. Note that the first value sets have only recently been published [14,15,16,17].

The EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol recommends the valuation of childhood-specific health states by the general population with both composite time trade-off (cTTO) and discrete choice experiment methods. However, in contrast to what is prescribed in the valuation of adult EQ-5D instruments (where adults are asked to imagine how EQ-5D health states pertain to themselves), respondents are asked to value a 10-year-old child’s health state [12]. Hence, a different perspective is recommended compared to adult EQ-5D valuation. Earlier work has shown that valuation can systematically differ between perspectives [13, 18,19,20,21]. Such work has, for example, explored the effect of asking respondents to take another person’s perspective (either another child or adult, [21]), compared adults and adolescents taking their own perspective [19], or even asked adult respondents to value states imagining they were 10-year-old children [21, 22]. To date, it is not clear how and why such changes in perspective in EQ-5D-Y-3L affects valuation [23], warranting further exploration of the influence of perspective in EQ-5D-Y valuation.

Tsuchiya and Watson [24] provide a useful classification of different perspectives that can facilitate such further exploration. The perspective recommended for valuation of EQ-5D-Y-3L may constitute a proxy perspective in the Tsuchiya and Watson [24] classification system, as individuals’ views about a person other than themselves are elicited. However, there is a slight difference between the perspective introduced in the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol, and how proxy perspectives are defined in the classification by Tsuchiya and Watson [24]. That is, Tsuchiya and Watson write that a proxy perspective is asking for a respondent’s estimate of other peoples’ personal preferences. Instead, in valuation of EQ-5D-Y-3L, adult respondents are asked to make a decision that they themselves consider best for a 10-year-old child [12]. As the protocol provides no further context to these valuation tasks, it remains unclear whether respondents should (paternalistically) decide what is best for a child or instead should decide by approximating what a child would want for itself.

In this study, our main motivation was to explore the influence of asking respondents to explicitly take into account what a 10-year-old child would want for itself on valuation of EQ-5D-Y-3L health states. To this end, we asked respondents to value EQ-5D-Y-3L health states with two different proxy perspectives. Both perspectives resemble types of proxy reporting included in the EQ-5D-Y user guide, which may be used with young children or patients with cognitive or physical impairments [25, 26]. In the user guide, two types of proxy reporting are discussed: proxy 1 and proxy 2. Proxy 1 reporting involves the proxy (e.g. parent, caregiver) reporting EQ-5D-Y by providing their own impression of the child’s health, whilst proxy 2 reporting involves asking proxies to rate how they think the child would report their health themselves if they were able to. In line with these types of proxy reporting, we ask respondents to value EQ-5D-Y-3L health states considering what they think is best for a 10-year-old child (as is recommended in the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol) or instead considering what the child would want for itself. We will refer to these perspectives as using a proxy 1 or a proxy 2 (substitute) perspective. Given that the latter perspective resembles individuals substituting their family members’ treatment preferences (when no power of attorney or healthcare directive is available) in clinical decision making, it is referred to as using a proxy 2 (substitute) perspective.

To explore how the use of these two perspectives affects EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation, we compared the outcomes, dispersion and response patterns of cTTO valuation between respondents valuing EQ-5D-Y-3L with proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives. Note the exploratory focus of this study means that we formulated no a priori hypotheses about if, how and why these perspectives would yield differences in valuation.

2 Methods

All data for this study were collected as part of the Dutch EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation study [27]. As a result, the sample size and interview procedure are based on the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol [12]. Note that the EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol also involves discrete choice experiment data collection, which is not reported on in this article as it involved only the proxy 1 perspective. As recommended in the protocol, cTTO interviews were performed by a team of trained interviewers (four in total), whose performance was monitored during the study using well-established quality-control procedures [28]. Interviews were conducted in the Netherlands and were completed between November 2020 and January 2021, i.e. when the Netherlands was in a national lockdown because of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. As a result, interviews were facilitated with videoconference software (i.e. Zoom), in which interviewers used a shared screen to instruct respondents (for a discussion of the benefits and drawbacks of this approach, see [29, 30]).

2.1 Sample and Design

The EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation protocol recommends to use a sample of 200 respondents for cTTO valuation [12]. In this study, a marketing agency recruited a sample of 402 respondents to roughly balance sex, age and educational level, although no strict quota were in place. Respondents were randomly assigned (using the interview software) to complete a cTTO interview in either the proxy 1 (n = 197) or proxy 2 (n = 205) perspective (see Table 1 for respondents’ demographic characteristics). In each interview, respondents valued ten health states in their randomly assigned perspective, as well as one health state in the other perspective (for more information, see ‘Health states’). Hence, our design focused on between-subject comparisons as well as enabling a single within-subject comparison of cTTO valuations for proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives.

2.2 Health States

Respondents valued health states derived from EQ-5D-Y-3L, which can describe up to 243 unique health states. For brevity, EQ-5D states are often described by five digit codes, such as 21233 or 33333. The former would describe a state with some problems with walking about (level 2), no problems with washing and dressing (level 1), some problems with usual activities (level 2), a lot of pain or discomfort (level 3) and feeling very worried, unhappy or sad (level 3). The latter 5-digit code, 33333, thus refers to the worst possible state described by EQ-5D-Y-3L. An orthogonal design of 18 states was used, supplemented with an additional ten health states. More detail on the orthogonal design is described in Yang et al. [31]. The 28 states were divided into three blocks of ten states, each containing the worst health state, 33333. Each respondent valued 33333 in both assigned perspectives (i.e. this state was included for within-subject comparisons), the remaining states they valued depended on the block they were randomly assigned to (see Appendix A in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] for all included states). We chose to obtain repeated measurements for this state (i.e. from both perspectives) as the valuation of this health state may be used as an anchor to estimate value sets from both cTTO and discrete choice experiment data (among other possible approaches) [12].

2.3 Interview Procedure

Each interview commenced by respondents reporting a set of basic demographics (e.g. age and sex) followed by a set of questions on whether they had experience with providing informal care or illness in themselves, family or friends. Next, respondents self-completed EQ-5D-Y-3L to become familiar with the instrument, and rated their health on a visual analogue scale (henceforth: EQ-VAS). Next, respondents were familiarised with cTTO, through the procedure described by Stolk et al. [10]. As is usual for cTTO tasks in EQ-5D valuation [10, 12], cTTO was operationalised with a 10-year duration (followed by immediate death), and a 10-year lead time for states considered worse than dead. Importantly, depending on the condition, respondents were randomly assigned to cTTO, either operationalised with a proxy 1 or proxy 2 (substitute) perspective. In the proxy 1 perspective, respondents were asked to complete cTTO considering what they thought was better for a 10-year-old child. When respondents completed cTTO from a proxy 2 (substitute) perspective, they were asked to consider what a 10-year-old child would want for itself. After resolving any remaining uncertainty respondents might have had about the task, respondents completed their assigned block of ten health states in random order. Finally, state 33333 was valued again from the non-assigned perspective. As is recommended in EQ-5D valuation [10, 32], cTTO interviews were finalised by the use of a feedback method. This method involves ranking all health states by their implied utility and asking respondents to reflect on this ordinal ranking. For each state, respondents had the opportunity to point out states that were out of place (referred to as ‘flagged states’). Although these states may be excluded from further calculations, it has been found that such an exclusion has little effect on the results [32]. Hence, in this study, the results of this method will be interpreted as an indication of the quality of collected data, rather than a reason for excluding responses. Interviews were concluded by collecting a set of additional demographic information (including parental status and EQ-5D-5L).

2.4 Data Analysis

To explore the differences in cTTO valuation between proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives, we analyzed the data in three domains: (1) outcomes, (2) dispersion and (3) response patterns.

2.4.1 Outcomes

The outcomes of the cTTO valuation were compared between the proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives by running a set of regression models aimed at identifying the importance of EQ-5D-Y-3L dimensions as well as exploring the within-subject effects of using proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives by comparing valuations for state 33333. The following modelling strategy was used. First, we ran a set of regression models on (subsets of) the outcomes of the cTTO valuation. These regressions model the disutility associated with each of the levels per EQ-5D-Y-3L dimension. However, it is well known that the variance for cTTO utilities is larger for more severe states [10, 33], which will lead to heteroscedasticity biasing regression results. As such, we modelled the valuation data while accounting for heteroscedasticity in error terms, as in Ramos-Goñi et al. [34]. Furthermore, we constrain the models such that the constant is dropped.

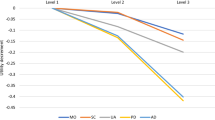

For models 1 and 2, a simple main-effects modelling approach is used, in which all data pertaining to a particular perspective are included. The main effects for EQ-5D-Y-3L are modelled by creating dummies of the form Dj, indicating whether some dimension is at level j. As in earlier EQ-5D-Y-3L studies, we will use the conventional EQ-5D abbreviations for brevity, i.e. MO, UA, SC, PD and AD for mobility, usual activities, looking after myself, pain or discomfort, and feeling sad, worried or unhappy, respectively [14]. Model 1 uses all health states valued in the proxy 1 perspective, and model 2 includes all health states valued in the proxy 2 (substitute) perspective. Model 3 uses the same approach but instead included all cTTO data, elicited in both perspectives. To model the effect of perspective, a dummy is included that tracks the perspective used (i.e. perspective is added as a covariate). We also explore possible interactions between the perspective used and EQ-5D-Y-3L dimensions in Model 4, by including interaction terms between dimension and perspective dummy variables.

Note that each model is included to answer a different question. Models 1 and 2 are included to find out the importance of EQ-5D-Y dimensions in proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives, respectively. Comparing model coefficients between models 1 and 2 informs us of differences in importance between perspectives, but no tests of significance is included. Model 3, by including perspective as a covariate, directly explores whether across all states a difference exists between both perspectives. Model 4 explores the effect perspective has on each of the EQ-5D-Y dimensions separately, which provides further substantiation of (any) effects found in Model 3, i.e. perhaps differences between proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives are particularly pronounced for one dimension and not others.

In order to test the robustness of our results, we also ran three additional sets of regression analyses reported in Tables A3–A5 of the ESM. First, we tested the sensitivity of our findings to the inclusion of repeated measurements for state 33333. Second, we ran models including demographics. Third, we ran models that included the constant. Our main conclusions were robust to including repeated measures. However, including demographics suggested that cTTO utilities in the proxy 2 (substitute) perspective, but not the proxy 1 perspective were affected by age, sex and parental status. The goodness of fit for models with a constant included was lower than the models reported in Table 3.

2.4.2 Dispersion

The dispersion of cTTO valuation was investigated with two separate analyses. First, we analyzed dispersion within-subjects, i.e. we considered the spread of cTTO responses for each respondent, by calculating within-subject variance across the ten unique states they valued. A smaller spread would indicate that valuations were more condensed (i.e. indicating respondents find it more difficult to distinguish between different health states), whereas a larger spread indicates the opposite (less condensed). Second, we analyzed dispersion between subjects by testing for the equality of variances for each health state, as earlier work has found that some perspectives may yield more heterogeneous cTTO data than others [21].

2.4.3 Response patterns in cTTO

Valuation were adapted from the quality assurance programme implemented by Alava et al. [35]. That is, we compared the degree to which the following response patterns occurred between proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives: (1) the same utility for each state, (2) fewer than five unique observations (out of ten states),Footnote 1 (3) no negative utilities, (4) no use of 0.5-year increments,Footnote 2 (5) weak dominance violation for state 33333 (i.e. assigning state 32333 the same or lower value than 33333), (6) strict dominance violations (e.g. lower utility for 11112 than 22222), (7) non-trading responses (utilities of 1), (8) all-in trading responses (utilities of − 1), (9) rounding (only utilities of − 1, − 0.5, 0, 0.5 or 1), and finally (10) flagged states in the feedback method. Note that only analyses 7 and 8 were performed including the repeated measurement for state 33333.

3 Results

Table 1 shows the demographics of the sample, and Table 2 shows self-reported health with EQ-5D-Y-3L. To test if randomization was successful, we tested if the part of the sample assigned to the proxy 1 perspective differed from that assigned to the proxy 2 (substitute) perspective for all demographics. We found no evidence against homogeneity, suggesting randomization was successful and no differences existed between the part of the sample that was assigned to the proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspective, respectively (Chi-squared tests for proportions, all p values > 0.09). Most respondents were female and/or highly educated. Furthermore, our sample contained very few people reporting the highest level of problems on any of the EQ-5D-Y-3L dimensions, suggesting that the sample consisted of mostly healthy respondents. Respondents’ EQ-5D-5L responses are reported in Appendix A of the ESM.

3.1 Outcomes of cTTO Valuation

Mean utilities for all health states included, as well as a figure displaying the full distribution of cTTO utilities per perspective, can be found in Appendix A of the ESM.

3.1.1 Modelling the cTTO Outcomes Using a Regression Analysis

Table 3 shows that EQ-5D-Y-3L main effects are significant and positive (as would be expected), with only SC2 in Model 1 being marginally significant. Comparing regression coefficients between Models 1 and 2 suggests that although the importance of EQ-5D-Y-3L dimensions appears similar, the disutilities differ between perspectives. The largest discrepancies occur for AD3, PD3 and UA3. In Appendix A of the ESM, the influence these discrepancies may have on all 243 EQ-5D-Y-3L states is shown. Furthermore, both Models 3 and 4 show that there is no overall effect of perspective, as the main effect of perspective is not significant in both models. Including interactions appeared to yield a better understanding of the effect of perspective, as well as why the effect of perspective in Model 3 is not significant. That is, Model 4 shows that with one exception, the interaction coefficients of the physical functioning domains of EQ-5D (MO, SC and UA) are positive. This could suggest that problems with physical functioning receive larger disutilities when considered from the perspective of what a child would want for itself rather than deciding for them. However, these interaction terms are not significant. In contrast, the interaction terms between perspective and PD3 and AD3 are significant and negative, suggesting that being in a lot of pain or being very sad, worried or unhappy yields lower disutilities when individuals consider what a child wants for itself (proxy 2 perspective) rather than decide for them (proxy 1 perspective).

3.1.2 Within-Subject Comparisons for State 33333

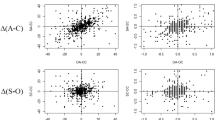

As each respondent valued state 33333 from both perspectives, comparing the outcomes of these valuations within-subjects can help identify heterogeneity. These responses are plotted in Fig. 1. Both the spread and density of this scatterplot show that most individuals valued state 33333 as − 1 in both perspectives, or higher for the proxy 2 (substitute) perspective. Indeed, most respondents (43.0%) traded off all children’s available life-years to avoid life in 33333 in both perspectives. If respondents valued states differently between perspectives, this predominantly led to lower valuations in the proxy 1 perspective (37.7%). However, if 33333 was valued as − 1 in the proxy 2 (substitute) perspective, an effect in this direction was not possible (because of cTTO censoring utilities at − 1, see Stolk et al. [10]). When we excluded all respondents for whom such a floor effect may have occurred (i.e. with utilities of − 1 for 33333 in the proxy 2 perspective), we found that 102, 84 and 77 respondents valued 33333 lower, equal and higher in the proxy 1 perspective than the proxy 2 (substitute) perspective, respectively.

3.2 Dispersion of cTTO Valuation

Although there is some heterogeneity between the health state blocks, compiled across all blocks within-subject variance is systematically lower for valuations in the proxy 2 (substitute) perspective (mean = 0.24, standard deviation = 0.25) than in the proxy 1 perspective (mean = 0.33, standard deviation = 0.29), t(389) = 3.38, p < 0.001. This suggests that respondents’ valuations were more compressed when considering what a child would want for itself.

Whereas earlier work found evidence for differences in dispersion between subjects [21], in this study, these effects occurred in either direction. That is, Appendix A of the ESM shows that although standard deviations were larger for proxy perspectives in 11 out of 28 health states, the opposite applied for the remaining 17 states. In fact, using Bartlett’s tests for homogeneity of variances we found evidence against the equality of variances for a total of 12 states (all p values < 0.05). In particular, variance was significantly larger in the proxy 1 perspective rather than the proxy 2 (substitute) perspective for states 11112, 11313, 12331, 21111, 21332, 31223, 32232, 11211, 12111 and 22121, whereas the opposite held for states 11121, 11211, 12111 and 22121. Notably, there is no evidence against homogeneity of variances for state 33333. These analyses thus suggest that variances may differ between perspectives, but it is unclear in which direction.

3.3 Response Patterns in cTTO Valuation

Table 4 shows the results of our analyses of response patterns in cTTO valuation in both perspectives. The most occurring response patterns appeared to be the avoidance of negative utilities, which was more pronounced for proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives than proxy 1 perspectives (\({\chi }^{2}\left(1,N=402\right)=11.06, p<0.001\)). In fact, the proportion of states rated worse than dead was lower in the proxy 2 (355 out of 2237, 15.9%) than the proxy 1 perspective (447 out of 2175, 20.6%). We also find more evidence for all-in trading (i.e. utilities of − 1) responses for the proxy 1 perspective (\({\chi }^{2}\left(1,N=4412\right)=18.71, p<0.001)\). This suggests that a larger proportion of respondents deciding for a child were willing to give up all of their lifetime to avoid living in some EQ-5D-Y-3L health state (compared to respondents considering what children would want for themselves). As a result, the cTTO tasks completed in the proxy 1 perspective yielded more observations that are censored at − 1, and, thus this may also explain the larger proportion of states valued equal to or lower than 33333 (\({\chi }^{2}\left(1,N=3609\right)=8.62, p=0.003)\) in the proxy 1 perspective. No other differences were observed in response patterns between the two perspectives (Chi squared, all p values > 0.05).

4 Discussion

The results reported in this paper confirm earlier findings suggesting that health state valuation with different perspectives yield different responses [13, 18,19,20,21]. Our results suggest that for mild health states, little to no differences are observed between proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives. Such results are in line with earlier studies that found small or no differences between valuation outcomes with different perspectives [21, 36]. However, we find that the use of different operationalisations of proxy perspectives in cTTO will lead to systematically different results for states involving considerable pain and anxiety and/or when children are very sad, worried or unhappy. Furthermore, within-subject analyses for state 33333 show considerable heterogeneity, in line with earlier studies that found differences for this and other very severe EQ-5D-Y-3L states [13, 20]. Hence, we only find differences between deciding for a child and considering what a child wants for severe states.

Our analyses, however, provide little insight into why this effect only occurs for severe states and different explanations are possible. Perhaps this result is unsurprising, as respondents have more heterogeneous views for more severe states regardless of the perspective (i.e. heteroskedasticity), and, as such, differences are naturally larger for severe than for mild states. It also seems intuitive that the difference between deciding for a child and considering what a child wants is more pronounced when considering severe impairments rather than mild impairments. For example, respondents may not want to be responsible for children suffering, and as a result, they trade off more years when they have to decide what is best, even though this is not what they expect a child would want for itself. For milder states, they may be less inclined to consider themselves responsible for suffering (as there is less suffering). Alternatively, respondents may expect that a child assigns more importance to life duration itself, leading to fewer years traded off in a proxy 2 (substitute) perspective. Yet, our data do not allow directly testing this, which may be explored in subsequent research that measures discounting in different perspectives, as in [36].

Qualitative studies performed in EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation could also provide some insights into these processes [22, 37]. However, seeing as adults are unlikely to know or anticipate what a child wants, it appears relevant to contrast our results to earlier or future work comparing time trade-off valuation in adults and children or adolescents. To our knowledge, only a few studies exist [38], which point to effects in the opposite direction as observed here (children/adolescents gave up more years than their parents for the same state). Future work comparing valuation between adults and children should particularly explore if differences exist in the propensity to consider states worse than dead. Our findings suggest that adults are less inclined to do this when using a proxy 2 (substitute) rather than a proxy 1 perspective. If, as adults appear to anticipate, children consider fewer states worse than dead, this may caution against using proxy 1 perspective valuation. Yet, in this study, the different proportions of negative utilities in this study could be driven by the use of cTTO and its 10-year (lead time) duration followed by death (some issues of this method are discussed in [23]). Finally, our work also suggests that the effect of perspective on valuation of the worst state described by EQ-5D-Y-3L is considerable and highly heterogeneous. This may cause issues for the use of this state for scaling the outcomes of discrete choice experiment tasks to the QALY scale in valuation of EQ-5D-Y-3L, which is one of the ways value sets for EQ-5D-Y-3L have been anchored on the QALY scale [14].

We also found differences in dispersion and response patterns between EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation with proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives. The spread of cTTO utilities across the severity scale was smaller for respondents valuing EQ-5D-Y-3L with a proxy 2 perspective (compared with a proxy 1 perspective). In part, such a reduced spread may be an artefact of respondents giving up less time in cTTO in a proxy 2 (substitute) perspective, as this would yield a smaller difference between the highest and lowest valued health state. However, it can also be interpreted as respondents considering EQ-5D-Y-3L states to be more alike when considering what a child would want for itself. As such, this result could suggest that respondents are less able to distinguish between different EQ-5D-Y-3L states when considering what a child wants for itself, which may cause concern when it decreases the ability of the instrument to measure incremental changes between states. We also investigated in which perspective views about a health state were more heterogeneous between respondents, and found evidence in both directions. Finally, although response patterns differed between the two perspectives, it is not entirely clear if this should be interpreted as better data quality. For example, we find fewer negative utilities for the proxy 2 (substitute) perspective. Alava et al. [35] include a lack of negative utilities in their EQ-5D-5L quality assurance programme, but one could question the problematicity of (a lack of) such responses in EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation. Whereas in valuation of adult EQ-5D instruments one may expect negative utilities to occur frequently, and interpret a lack thereof as problematic, it is not clear if this should apply to EQ-5D-Y-3L [13]. Nonetheless, the lower prevalence of all-in trading (and coincidingly states valued the same as 33333) responses observed in the proxy 2 (substitute) perspective may be seen as an improvement in data quality as they signal reduced clustering of utilities at − 1.

In addition to yielding some evidence that the outcomes, dispersion and response patterns of a health state valuation are dependent on the perspective used, our findings may also have implications in the broader context of child and adolescent health state valuation. First, our work was motivated by a discrepancy between the perspective proposed for an EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation [12] and how proxy perspectives have been defined in the classification by Tsuchiya and Watson [24]. Whereas a proxy perspective, according to Tsuchiya and Watson [24], requires estimating another person’s preferences, in valuation of EQ-5D-Y-3L respondents consider what they think is best for a child. Our work shows that this slight change in how proxy perspectives are operationalised has a substantial impact for severe states. That is, this difference between the proxy perspectives was larger than, for example, the minimally important difference estimated for EQ-5D-5L [39, 40], or the mean QALY gain in a systematic review cost-utility analysis [41]. It is, however, important to note that severe health impairments may be unlikely in children in practice.

Nonetheless, the results of this paper should be interpreted taking into account a few limitations. First, our results suggest that the effect of perspective was most apparent for severe states, but this could be in part driven by the inclusion of repeated observations only for state 33333. Although our orthogonal design allowed estimating EQ-5D-Y-3L utilities for all 243 states, future research aiming to explore differences between proxy 1 and proxy 2 (substitute) perspectives may consider reducing the number of states included to increase the number of observations per state (or include more and milder states for within-subjects comparisons). This would increase the test power, and could help with exploring the differences between both proxy perspectives for mild states. Alternatively, the same design can be used with a larger sample size. Second, although our quantitative analyses help in understanding how the use of different perspectives affects the data obtained from cTTO tasks in an EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation, they provide little insight into the decision processes underlying the data. Such insight is needed, as our study, for example, cannot clarify if differences between perspectives are related to respondents considering EQ-5D-Y-3L states more or less severe or due to differences in the propensity to trade-off life duration between the two perspectives. Experimental (e.g. [36]) and qualitative (e.g. [37]) studies may help in providing such insight. Third, the sample used in this study was made up of Dutch citizens and predominantly women and highly educated respondents. Given that cultural values [42], and demographics such as education level and sex [43] are known to affect a health state valuation, it is unclear if our results replicate in other populations. Finally, these data were collected in the middle of a global pandemic. This may have influenced our results through a number of mechanisms. For example, all data were collected through online interviews, and there are only some papers that have tried to compare outcomes between these modes of administration, but generally found no differences [29, 30]. More importantly, the global health crisis following the outbreak may have affected valuation in our study. One may also expect that the importance of some dimensions has changed, or is more relevant to our purposes, that parents’ perceptions on what matters to their children has changed as a result of lockdown measures. Future work may explore if these effects occurred, and if they did, how permanent they are.

5 Conclusions

To conclude, our paper shows that asking respondents what they consider best for a child, as is recommended for an EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation [12], will yield different cTTO valuation than asking respondents to consider what a child wants for itself. When these cTTO valuations are used to generate utilities for all EQ-5D-Y-3L health states, differences between perspectives are sufficiently large to warrant careful consideration of which of these proxy perspectives is more suitable for an EQ-5D-Y-3L valuation. However, deciding the appropriate perspective for valuation is ultimately a normative question [44], suggesting that further conceptual research, as well as discussions with stakeholders such as the general public and decision makers remains relevant.

Notes

Low-quality responses may be identified by respondents inadequately distinguishing between different states by assigning many of them the same utility. In this case, we flagged respondents who had fewer than five ‘unique’ utilities, for example, out of ten states, four states were valued as 0.5, three states received an utility of 1 and 3 states received an utility of −0.9. In this case, three unique observations were observed: 0.5, 1 and −0.9.

In EuroQol Valuation Technology, cTTO allows the eliciting of indifference at a precision of 0.5 years, i.e. a granularity in terms of utilities of 0.05. Respondents were flagged if they had zero out of ten utilities (denoted \(U\), which signalled an indifference in half-year increments, i.e. formally

$$U\notin (-0.95, -0.85, -0.75, -0.65, -0.55, -0.45, -0.35, -0.25, -0.15, -0.05, 0.05, 0,15, 0.25, 0.35, 0.45, 0.55, 0.65, 0.75, 0.85, 0.95)$$.

References

Kwon J, Kim SW, Ungar WJ, et al. Patterns, trends and methodological associations in the measurement and valuation of childhood health utilities. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(7):1705–24.

Chen G, Ratcliffe J. A review of the development and application of generic multi-attribute utility instruments for paediatric populations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(10):1013–28.

Stevens K. Valuation of the child health utility 9D index. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30(8):729–47.

Ratcliffe J, Chen G, Stevens K, et al. Valuing Child Health Utility 9D health states with young adults: insights from a time trade off study. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2015;13(5):485–92.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Wille N, Badia X, et al. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the EQ-5D-Y: results from a multinational study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):887–97.

Wille N, Bonsel G, Burström K, et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):875–86.

Kreimeier S, Åström M, Burström K, et al. EQ-5D-Y-5L: developing a revised EQ-5D-Y with increased response categories. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(7):1951–61.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Kennedy-Martin M, Slaap B, Herdman M, et al. Which multi-attribute utility instruments are recommended for use in cost-utility analysis? A review of national health technology assessment (HTA) guidelines. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(8):1245–57.

Stolk E, Ludwig K, Rand K, et al. Overview, update, and lessons learned from the international EQ-5D-5L valuation work: version 2 of the EQ-5D-5L Valuation Protocol. Value Health. 2019;22(1):23–30.

Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, et al. The time trade-off method: results from a general population study. Health Econ. 1996;5(2):141–54.

Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Stolk E, et al. International valuation protocol for the EQ-5D-Y-3L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(7):653–63.

Kreimeier S, Oppe M, Ramos-Goñi JM, et al. Valuation of EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire, youth version (EQ-5D-Y) and EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) health states: the impact of wording and perspective. Value Health. 2018;21(11):1291–8.

Rupel VP, Ogorevc M. EQ-5D-Y value set for Slovenia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(4):463–71.

Shiroiwa T, Ikeda S, Noto S, et al. Valuation survey of EQ-5D-Y based on the international common protocol: development of a value set in Japan. Med Decis Making. 2021;41(5):597–606.

Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Estévez-Carrillo A, et al. Accounting for unobservable preference heterogeneity and evaluating alternative anchoring approaches to estimate country-specific EQ-5D-Y value sets: a case study using Spanish preference data. Value Health. 2022;25(5):835–43.

Kreimeier S, Mott D, Ludwig K, et al. EQ-5D-Y value set for Germany. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01143-9

Kind P, Klose K, Gusi N, et al. Can adult weights be used to value child health states? Testing the influence of perspective in valuing EQ-5D-Y. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(10):2519–39.

Mott D, Shah K, Ramos-Goñi J, et al. Valuing EQ-5D-Y health states using a discrete choice experiment: do adult and adolescent preferences differ? Med Decis Mak. 2021;41(5):584–96.

Shah KK, Ramos-Goñi JM, Kreimeier S, et al. An exploration of methods for obtaining 0= dead anchors for latent scale EQ-5D-Y values. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(7):1091–103.

Lipman SA, Reckers-Droog VT, Karimi M, et al. Self vs. others, child vs. adult: an experimental comparison of valuation perspectives for valuation of EQ-5D-Y health states. Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22(9):1507–18.

Powell PA, Rowen D, Rivero-Arias O, et al. Valuing child and adolescent health: a qualitative study on different perspectives and priorities taken by the adult general public. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):1–14.

Lipman SA, Reckers-Droog VT, Kreimeier S, et al. Think of the children: a discussion of the rationale for and implications of the perspective used for EQ-5D-Y health state valuation. Value Health. 2021;24(7):976–82.

Tsuchiya A, Watson V. Re-thinking ‘The different perspectives that can be used when eliciting preferences in health.’ Health Econ. 2017;26(12):e103–7.

Tamim H, McCusker J, Dendukuri N, et al. Proxy reporting of quality of life using the EQ-5D. Med Care. 2002;40(12):1186–95. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3767939

Jokovic A, Locker D, Guyatt G, et al. How well do parents know their children? Implications for proxy reporting of child health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(7):1297–307.

Roudijk B, Sajjad A, Essers B, et al. A value set for the EQ-5D-Y-3L in the Netherlands. Pharmacoeconomics. Under review.

Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Slaap B, et al. Quality control process for EQ-5D-5L valuation studies. Value Health. 2017;20(3):466–73.

Lipman SA. Time for tele-TTO? Lessons learned from digital interviewer-assisted time trade-off data collection. Patient. 2021;14(5):459–69.

Rowen D, Mukuria C, Bray N, et al. Assessing the comparative feasibility, acceptability and equivalence of videoconference interviews and face-to-face interviews using the time trade-off technique. Soc Sci Med. 2022;309:115227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115227

Yang Z, Luo N, Bonsel G, et al. Selecting health states for EQ-5D-3L valuation studies: statistical considerations matter. Value Health. 2018;21(4):456–61.

Wong EL, Ramos-Goñi JM, Cheung AW, et al. Assessing the use of a feedback module to model EQ-5D-5L health states values in Hong Kong. Patient. 2018;11(2):235–47.

Golicki D, Jakubczyk M, Graczyk K, et al. Valuation of EQ-5D-5L health states in Poland: the first EQ-VT-based study in Central and Eastern Europe. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(9):1165–76.

Ramos-Goñi JM, Craig BM, Oppe M, et al. Handling data quality issues to estimate the Spanish EQ-5D-5L value set using a hybrid interval regression approach. Value Health. 2018;21(5):596–604.

Alava MH, Pudney S, Wailoo A, et al. The EQ-5D-5L value set for England: findings of a quality assurance program. Value Health. 2020;23(5):642–8.

Lipman SA, Zhang L, Shah KK, et al. Time and lexicographic preferences in the valuation of EQ-5D-Y with time trade-off methodology. Eur J Health Econ. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01530-1

Reckers-Droog VT, Karimi M, Lipman SA, et al. Why do adults value EQ-5D-Y-3L health states differently for themselves than for children and adolescents: a think-aloud study. Value Health. 2022;25(7):1174–84.

Trent M, Lehmann HP, Qian Q, et al. Adolescent and parental utilities for the health states associated with pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(7):583–7.

Walters SJ, Brazier JE. Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(6):1523–32.

McClure NS, Al Sayah F, Xie F, et al. Instrument-defined estimates of the minimally important difference for EQ-5D-5L index scores. Value Health. 2017;20(4):644–50.

Wisløff T, Hagen G, Hamidi V, et al. Estimating QALY gains in applied studies: a review of cost-utility analyses published in 2010. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(4):367–75.

Roudijk B, Donders ART, Stalmeier PF, et al. Cultural values: can they explain differences in health utilities between countries? Med Decis Mak. 2019;39(5):605–16.

Dolan P, Roberts J. To what extent can we explain time trade-off values from other information about respondents? Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(6):919–29.

Rowen D, Rivero-Arias O, Devlin N, et al. Review of valuation methods of preference-based measures of health for economic evaluation in child and adolescent populations: where are we now and where are we going? Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(4):324–40.

Acknowledgements

This paper was discussed at the Lowlands Health Economics Study Group, the authors acknowledge discussant Elly Stolk for her suggestions for improvement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was made possible through funding provided by the EuroQol Research Foundation (project number: 100-2020VS). The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of the EuroQol Group.

Conflict of interest

All authors have received funding from the EuroQol Research Foundation for work outside the scope of this research. Bram Roudijk, Aureliano Finch, Peep Stalmeier and Brigitte Essers are members of the EuroQol Group, and Bram Roudijk and Aureliano Finch are currently employees of EuroQol.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was provided by the Erasmus School of Health Policy and Management’s Ethical Review Board (reference: Lipman 20-25).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

All participants provided informed consent for publication of the results of the data they provided in academic research.

Code availability

All analysis code is available from the first and last author of this paper upon reasonable request.

Availability of data and material

Requests for access to this data can be directed to EuroQol: http://www.euroqol.org.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: APF, BR. Methodology: SAL, BABE, APF, PFMS, AS, BR. Data acquisition: BR. Formal analysis and investigation: SAL. Writing, original draft preparation: SAL. Writing, review and editing: SAL, BABE, APF, PFMS, AS, BR. Funding acquisition: SAL, BABE, APF, PFMS, AS, BR. Supervision: APF, BR.

Disclosure statement

This article has been published in a special edition journal supplement wholly funded by the EuroQol Research Foundation

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lipman, S.A., Essers, B.A.B., Finch, A.P. et al. In a Child’s Shoes: Composite Time Trade-Off Valuations for EQ-5D-Y-3L with Different Proxy Perspectives. PharmacoEconomics 40 (Suppl 2), 181–192 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01202-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01202-1