Abstract

As part of its Single Technology Appraisal (STA) process, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) invited the manufacturer (GlaxoSmithKline [GSK]) of Benlysta (belimumab) to submit evidence regarding its clinical and cost effectiveness, for the review and possible extension of a previously conditionally approved intravenous formulation of belimumab for the treatment of active autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Kleijnen Systematic Reviews Ltd, in collaboration with Maastricht University Medical Centre+, was commissioned to act as the independent Evidence Review Group (ERG). This paper summarises the company submission (CS), presents the ERG’s critical review of the clinical and cost-effectiveness evidence in the CS, highlights the key methodological considerations, and describes the development of the NICE guidance by the NICE Appraisal Committee.

This appraisal is different to the previous appraisal in three ways: (1). This appraisal expands its definition of ‘high disease activity’. (2). In TA397, belimumab was approved, with a managed access arrangement (MAA), for adults only. This appraisal includes subjects aged 5 years or older. (3). The original appraisal included an intravenous formulation only, but the current appraisal also includes a new subcutaneous formulation in the form of a prefilled pen.

The company was required to collect real-world data from the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Biologics Register (BILAG-BR), including data on the efficacy, safety, and effect on health-related quality of life of belimumab versus rituximab. This appraisal considers these data as well as additional clinical trial evidence presented in the company’s updated submission to address uncertainties identified during the original appraisal. The ERG identified three major concerns with the evidence presented on the clinical effectiveness in the current submission; namely, short follow-up in the main comparative trials (BLISS-SC, BLISS-52 and BLISS-76); using the propensity score-matching (PSM) analysis in calibrating the cost-effectiveness model can severely bias the results in favour of belimumab; and BILAG-BR data are not suitable for a comparison of belimumab with rituximab.

The main issue in the economic analysis was the uncertainty about long-term disease activity progression and resulting organ damage. The company’s approach of calibrating modelled organ damage to longer-term data analysed using the PSM analysis was methodologically inappropriate. The final analysis comparing belimumab with standard treatment for the intravenous formulation resulted in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of £12,335 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained and £30,278 per QALY gained in the company’s and ERG’s base-case analyses, respectively. For the subcutaneous formulation, the final analysis resulted in £8480 per QALY gained and £29,313 per QALY gained in the company’s and ERG’s base-case analyses, respectively. NICE recommended belimumab in both intravenous and subcutaneous formulations as an add-on treatment option for active autoantibody-positive SLE in the HDA-2 subgroup.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The comparison with rituximab was made difficult because data collected to make a comparison between belimumab and rituximab were unsuitable for this comparison. Furthermore, the National Health Service (NHS) England recommended that patients be prescribed belimumab prior to rituximab, which made it an inappropriate comparator. |

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of belimumab compared with standard treatment ranged between £8480 and £68,909 with different model assumptions. |

The largest uncertainty in this population was in the long-term comparative effectiveness and, indeed, disease activity progression and resulting accumulation of organ damage. Further data on this should be collected. |

1 Introduction

Belimumab, tradename BenlystaTM, was reappraised within the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) single technology appraisal (STA) process as Technology Appraisal 752 (TA752). Health technologies must be shown to be clinically effective and to represent a cost-effective use of National Health Service (NHS) resources to be recommended by NICE. Within the STA process, the company (GlaxoSmithKline [GSK]) provided NICE with a written submission and an economic model summarising the company’s estimates of the clinical and cost effectiveness of belimumab for the treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in subjects with high disease activity despite standard treatment (ST).

This company submission (CS) was reviewed by an Evidence Review Group (ERG) independent of NICE. The ERG, Kleijnen Systematic Reviews in collaboration with Maastricht University Medical Centre+, produced the ERG report [1]. After consideration of the evidence submitted by the company, as well as the ERG report, the NICE Appraisal Committee (AC) issued guidance on whether to recommend the technology by means of the Final Appraisal Determination (FAD), to which an appeal can be made. This paper presents a summary of the ERG report and the development of the NICE guidance. Furthermore, it highlights important methodological issues that were identified that may help in future decision making.

The previous TA of belimumab (TA397) ended in a managed entry agreement, requiring the company to gather further evidence. As a result, the company collected data from the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Biologics Register (BILAG-BR).

Full details of all relevant appraisal documents (including the appraisal scope, CS, ERG report, consultee submissions, technical engagement, FAD, and comments from consultees) can be found on the NICE website (https://www.nice.org.uk) [2].

The ERG reviewed the clinical- and cost-effectiveness evidence of belimumab for this indication. As part of the STA process, the ERG and NICE had the opportunity to ask for clarification on specific issues in the CS, in response to which the company provided additional information. The ERG also produced an ERG base-case to assess the impact of alternative assumptions and parameter values on the model results, by modifying the economic model submitted by the company. Sections 2–4 summarise the evidence presented in the CS as well as the review by the ERG.

2 The Decision Problem

The population defined in the scope was “People aged 5 years or more with active, autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus with a high degree of disease activity despite standard therapy” [3]; the scope did not provide a definition for ‘a high degree of disease activity’. In the CS, the company provided two definitions:

-

High Disease Activity Subgroup-1 (HDA-1): Patients with a SELENA-SLEDAI (SS) score ≥ 10 AND low complement AND positive anti-dsDNA (current NICE guidance population; TA397)

-

High Disease Activity Subgroup-2 (HDA-2): Patients with an SS score ≥ 10 AND at least one of the following serological features: low complement OR positive anti-dsDNA—the base-case

The current appraisal is different from the original appraisal (TA397) [4] in three ways:

-

The company applies to change the definition of ‘high disease activity’ from HDA-1 to HDA-2.

-

In TA397, belimumab was approved for adults only. This appraisal includes individuals aged 5 years or older.

-

The original appraisal included an intravenous formulation only, but the current appraisal also includes a new subcutaneous formulation.

The company acknowledged that patients with severe active CNS lupus were excluded from the BLISS trials and no evidence to support the use of belimumab is available in this population [5]. Patients with lupus nephritis (LN) were also excluded from the BLISS trials. In addition, the ERG asked whether literature searches had been performed about the effect of belimumab on individuals between the ages of 5 and 18 years. The company confirmed that “no searches were performed in people over the age of five as the CS focuses on an adult population with SLE as does the economic modelling. The majority of clinical effectiveness data available on belimumab is for adult patients aged 18 years and older with SLE” [5].

The current appraisal (TA752) applied only standard therapy (ST) as a comparator, excluding rituximab and cyclophosphamide, which were mentioned in the scope.

The company only included one comparator, ST; however, the company provided several reasons why rituximab was not included as a comparator, including lack of data to perform an (indirect) comparison (even in BILAG-BR, data were not comparable between treatment populations). Furthermore, the company referenced the recently published NHS England commissioning policy for rituximab in the treatment of SLE, which stated that belimumab should be considered prior to rituximab in the treatment pathway [6, 7]. Cyclophosphamide was not included as a comparator because the company argued it was not frequently used in SLE [6].

2.1 Evidence Review Group (ERG) Critique of the Decision Problem

In the original appraisal (TA397), the Committee concluded that both standard care and rituximab should be comparators for belimumab, as included in the final scope and in the manufacturer’s decision problem [8]. The Committee also concluded that for the NICE TA guidance review, data regarding the comparison of belimumab with rituximab could be available through the BILAG-BR registry. However, the Committee was aware that cyclophosphamide may not be an ideal comparator as it was largely used for patients with LN and also due to its adverse events profile [8].

The opinion of our clinical expert in relation to the comparators was that cyclophosphamide is mostly used for neuropsychiatric lupus, severe vasculitis (e.g. gut), severe cardiorespiratory involvement, and patients who do not respond to mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) in the case of some of these types of conditions as well as for renal lupus. In addition, the adverse event profile means that cyclophosphamide is avoided if possible and rituximab is increasingly used for severe manifestations. According to our clinical expert, the comparison with rituximab would also be difficult because the evidence for rituximab is weaker, as the phase III trials were negative due to very stringent endpoints and are mostly from registries. Furthermore, the BILAG-BR data, requested to be collected as part of a Managed Access Agreement (MAA) following the original appraisal [9], cannot be used to compare rituximab and belimumab easily due to the different criteria for the use of rituximab and belimumab (see BSR guidelines [7, 10]).

Therefore, rituximab appeared to be a relevant comparator but with little evidence to inform that comparison.

3 Independent ERG Review

The CS presented three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of belimumab (BLISS-52 [11, 12], BLISS-76 [13, 14], and BLISS-SC [15, 16]), and each of the trials had an extension study [17,18,19,20]. Regarding this evidence, only the three RCTs and one of the extension studies (18) were included in the economic model. All three RCTs provided evidence for the two HDA subgroups presented in the CS. The company used a number of different disease measures (Appendix 1 presents a direct comparison of all measures used in this submission).

The main evidence for the clinical effectiveness of belimumab was from two phase III clinical trials. The BLISS-52 (n = 865) and BLISS-76 (n = 819) trials were randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group studies with follow-up at 52 weeks and 76 weeks, respectively. In these trials, belimumab plus ST was compared with placebo plus ST.

The BLISS-SC trial was presented in this submission to introduce the SC formulation of belimumab. The BLISS-SC trial is an international, multicentre, phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled trial lasting 52 weeks. Patients were randomised to subcutaneous belimumab 200 mg once weekly plus ST or placebo plus ST.

The results from the main trials (BLISS-SC and the pooled BLISS-52 and BLISS-76 data) were mostly favourable for belimumab in the HDA-2 subgroup. The primary outcome of all studies was the response rate at week 52 compared with baseline. This was assessed using the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Responder Index-4 (SRI-4), a composite measure of disease activity. Belimumab showed a statistically significant improvement in SRI-4 response rate at 52 weeks compared with ST in the HDA-2 population across the BLISS SC and pooled BLISS 52 and BLISS 76 trials (pooled BLISS 52 and BLISS 76: odds ratio [OR] 2.29, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.61–3.26; BLISS SC: OR 1.79, 95% CI 1.17–2.74). The committee concluded that belimumab improved SRI-4 response rate at 52 weeks compared with ST.

3.1 Critique of Clinical-Effectiveness Evidence and Interpretation

The critique from TA397 still stands. The SLE population in BLISS-76 is more likely to resemble that in the UK than the SLE population in BLISS-52; therefore, the BLISS-76 results are likely more relevant to the decision problem than the results from BLISS-52. Patients were required to be ≥18 years of age in both the BLISS-52 and BLISS-76 trials, and thus paediatric patients were excluded. No UK patients were enrolled in BLISS-52; however, in BLISS-76, a total of 11 patients from the UK were enrolled, constituting 1.3% of the total trial population. Of these 11 patients, six patients were randomised to placebo, four were randomised to the unlicensed belimumab 1 mg/kg dose, and one was randomised to the licensed 10 mg/kg dose.

Based on the total population included in the BLISS trials, over 90% of patients in each arm experienced one or more adverse events. Of these events, only diarrhoea and nausea occurred slightly more frequently in the belimumab groups than in the standard-care groups. Serious adverse events were experienced by 17% of patients in the belimumab 10 mg/kg group compared with 16% in the standard-care group.

The company performed a propensity score-matching (PSM) analysis that matched patients treated with belimumab (plus ST) in the BLISS-76 US Long-Term-Extension (BLISS-76 US LTE) study (primary analysis) with patients from the Toronto Lupus Cohort (TLC), a Canadian observational cohort study of patients treated with ST, to enable a long-term comparative analysis (6.5 years) of belimumab versus ST [21]. Organ damage from the BLISS-76 US LTE was then calibrated towards the organ damage calculated by the PSM, significantly increasing the organ damage that had been measured by the BLISS-76 US LTE. Despite requests for clarification, the method of calibration remained largely uncertain. The increase in organ damage brought on by the application of the calibration factor could result in a significant bias, as patients who remained in the LTE study were likely to have milder disease and milder adverse events compared with those who withdrew from belimumab treatment. Because only a maximum of 34% of the BLISS-76 trial patients were included in the PSM, the bias from using the calibration factor could be large. Additionally, by matching between BLISS-76 US LTE and the TLC, the PSM results may not generalisable to the UK.

Additional data comparing belimumab and rituximab were available from the BILAG-BR substudy [19]. This was an analysis of the BILAG-BR, an observational prospective cohort study of patients receiving hospital treatment for SLE in the UK. The eligibility criteria were defined by the NICE-recommended subgroup of the current licensed population for belimumab, and patients who had high disease activity (anti-dsDNA-positive, low complement 3 or 4 level and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 [SLEDAI-2K] score ≥10) were included from October 2013 onwards. Two primary endpoints of the BILAG-BR were BILAG-2004 and SLEDAI-2K. A disease-specific instrument (Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology [SLICC/ACR] Damage Index) was also used and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured using both generic and disease-specific instruments. However, BILAG-BR data cannot be used to make a reliable comparison of the effectiveness of belimumab versus rituximab due to the different criteria for the use of rituximab and belimumab (see BSR guidelines for SLE [10]).

4 Cost-Effectiveness Evidence Submitted by the Company

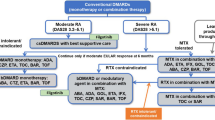

The company used a micro-simulation model with the same structure as in the previous STA (TA397) [22]. The general model structure was as follows: individually modelled patients started in the model with baseline patient characteristics and a treatment status (belimumab or ST). Patient characteristics and treatment status influenced disease activity, organ damage and mortality. If disease activity was high, this increased the estimated organ damage directly, and indirectly through a modelled increase in the use of corticosteroids. Yearly mortality risk was directly dependent on the baseline patient characteristics, disease activity and organ damage. A simplified overview of how treatment effectiveness (disease activity, corticosteroid use and organ damage) is informed can be found in Fig. 1.

The model adopted a healthcare perspective. The model time horizon was lifetime and was based on a 1-year cycle. All costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per year.

Both the patient populations (HDA-1 and HDA-2) as well as both treatment formulations (intravenous and subcutaneous) were considered in the economic evaluation. These two formulations were modelled separately, comparing each with ST. ST included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids and immunosuppressants. Patients receiving the intravenous formulation were modelled to receive 10 mg/kg at days 0, 14, and 28 and at 4-week intervals thereafter, meaning that these patients received 14 administrations in the first year and 13 administrations in every following year. Patients receiving the subcutaneous formulation were modelled to receive a 200 mg solution for injection every week, meaning these patients received 53 doses in the first year and 52 doses in each following year. While the final scope included ST alone, rituximab with ST, and cyclophosphamide with ST, only ST was included as a comparator in the model.

Baseline characteristics were drawn from the patient population of BLISS-52 [11, 19] and BLISS-76 [13] for the intravenous model population and from BLISS-SC [15] for the subcutaneous model population. The weight distribution was informed by the BILAG-BR [23]. Baseline organ damage was informed by a distribution of organ damage within the model population and was converted into baseline organ damage using the SLICC/ACR Damage Index (SDI).

The 1-year treatment effect based on disease activity was informed by the BLISS trials. A linear regression model was fitted to the trial data to extrapolate differences between baseline SS score and the SS score at week 52. The covariates used in the linear regression model were baseline SS score, a treatment indicator variable, and a ‘response’ variable.

Patients were considered to respond to treatment if they had a reduction in SS score of ≥ 4 at 24 weeks. If patients did not satisfy the necessary condition of response, they were marked as non-responders and were modelled to not receive belimumab anymore after the first model cycle. To inform response at 24 weeks, a Kaplan–Meier survival estimate was derived at a later measurement point (week 76 for the intravenous formulation, week 52 for the subcutaneous formulation). The response rate was then calculated using an assumption of a constant daily hazard rate. Discontinuation rates beyond the observed timeframe in the respective phase III trials were derived from an analysis of the LTE study data [11, 13, 19].

For responders in the belimumab arm, a reduction in disease severity and a related reduction in the use of corticosteroids was implemented based on BLISS-52 and BLISS-SC. The company assumed that disease activity reduction remained constant over time.

To measure disease activity over time, the SS score was used to calculate the adjusted mean SLEDAI (AMS) score. The AMS score was defined as the area under the curve of disease activity measurements between two time points divided by the duration between the two time points. For the long-term extrapolation of outcomes, data from a registry were used to derive a natural history model of disease activity [24]. The change in AMS score year-on-year was calculated by using a regression analysis including the following covariates: AMS in the previous period, male sex, Black ethnicity, and the log of age. To adjust for the lower baseline disease activity in the BLISS trial, the constant predicted by the regression analysis was increased manually.

To predict organ damage, time-to-event models were then used to establish the relationship between organ damage as measured by the Johns Hopkins data and various risk factors. For each affected organ, damage was estimated independently using survival curves including covariates for the following characteristics: past smoking, cholesterol level, hypertension anticardiolipin antibody positivity and lupus anticoagulant positivity.

The company argued that as patients in the BLISS trial had lower baseline disease activity than the Johns Hopkins cohort, and because the PSM resulted in a much larger difference in organ damage between belimumab and ST, the effect of belimumab on organ damage was underestimated. Therefore, the company made two adjustments. First, to adjust for different disease activity at baseline when comparing the BLISS trial population and the Johns Hopkins cohort, the SS score at baseline in the Johns Hopkins cohort was adjusted upwards. This was done by evaluating a range of baseline SS scores until the resulting curve provided a reasonable fit to the data. Second, the company adjusted the effect of belimumab on organ damage by calibrating modelled organ damage at 5 years into the modelled time horizon to the results of the PSM at 5 years. This was done by estimating a calibration factor (multiplicator) to the SDI score that would yield an SDI score close to that of the belimumab cohort of the PSM. The resulting calibration factor was then applied after the period that could be directly informed by the BLISS-72 trial at 1.5 years, i.e. at 6.5 years into the modelled time horizon. The modelled SDI score was assumed to linearly approach the calibrated SDI score at 6.5 years. The calibration factor was implemented for the belimumab treatment arm of the model only, thereby leaving the ST arm unadjusted.

Time to death conditional on AMS was modelled using a Weibull survival model based on the Johns Hopkins cohort data. Mortality was further adjusted to account for background mortality.

No adverse events were included in this submission, with the company claiming that few differences in adverse events had been observed between the intervention and comparator arms of the BLISS trials.

HRQoL was calculated based on a utility function of SS score and sex (male/female) and Black ethnicity, based on data from BLISS-52 and BLISS-76. According to the company, the influence of organ damage measures on HRQoL was not significant in the estimates based on the BLISS data. This could be explained by the SS score having a higher explanatory value. Instead, utility multipliers from the literature were used to incorporate disutilities associated with sustained organ damage. Different types of damage to the organ systems were weighted according to their incidence and divided by the total number of corresponding events in the respective organ system.

The model included costs and resource use for treatment costs, treatmentadministration costs, disease activity-related costs and key organ damage costs. The list price for the intravenous infusion was set at £121.50 per 120 mg vial and £405.00 per 400 mg vial, and £222.75 for a 200 mg prefilled pen for the subcutaneous formulation. A confidential patient access scheme (PAS) price was offered by the company for both formulations. Disease activity-related costs were based on a linear regression analysis of phase II trial data [22] that related the SS score to average yearly costs. Costs of organ damage were calculated by multiplying the frequency of organ damage with its cost.

The company’s base-case analysis, excluding the PAS, resulted in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £29,162 per QALY gained for the intravenous formulation and £30,566 per QALY gained for the subcutaneous formulation [2]. A deterministic sensitivity analysis was conducted varying individual parameters using a 95% CI. In both the intravenous and subcutaneous formulation models, the most impactful factors were the AMS score coefficient for predicting pulmonary organ damage, the discontinuation rate following 2 years of treatment, and the treatment effect of belimumab at week 52. The company further conducted a probabilistic analysis with 1000 iterations. The probabilistic analysis (excluding the PAS) resulted in an ICER of £31,629 per QALY for the intravenous formulation and £29,264 per QALY for the subcutaneous formulation, with a probability of approximately 40% for the intravenous formulation to be cost-effective and 50% for the subcutaneous formulation to be cost-effective at a £30,000 willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold. After the company’s PAS was added, the analysis resulted in an ICER of £12,335 per QALY gained for the intravenous formulation and £8480 per QALY gained for the subcutaneous formulation. The model was validated by the company by applying model convergence checks, testing model accuracy compared with the Johns Hopkins cohort, and by checks for formula and functional errors.

4.1 Critique of Cost-Effectiveness Evidence and Interpretation

4.1.1 Comparators Not According to Scope

The ERG was concerned about the exclusion of the potentially relevant comparators rituximab and cyclophosphamide. Clinical expert advice indicated that cyclophosphamide would rarely be used for SLE and that the adverse event profile was not favourable compared with belimumab. The exclusion of cyclophosphamide was therefore deemed acceptable.

As stated in Sect. 2, rituximab appeared to be a relevant comparator, but with little evidence to inform that comparison.

4.1.2 No Direct Comparison of the Intravenous and Subcutaneous Formulations

The ERG considered that the intravenous and subcutaneous formulations could have been included in the same model and compared with ST in a fully incremental analysis. The issue was considered as resolved as clinical experts considered there to be a similar efficacy between the formulations, while prices were equally comparable.

4.1.3 Application of Calibration Factor

The main issue identified by the ERG related to calibrating organ damage in the model to match that based on the PSM. The ERG considered the company’s calibration factor to be questionable due to several reasons:

-

(a)

There were several issues with the PSM. First, the set of patients that was obtained through the PSM was not more generalisable to the UK setting than the original TLC sample. Second, it was questionable whether the results of the PSM were applicable to the HDA-2 population as the PSM was conducted on the LTE trial. Finally, there were methodological issues, relating to (1) unobserved differences between the BLISS LTE and TLC studies; and (2) the fact that the BLISS LTE studies followed only patients continuing to use belimumab and who were likely to respond well to belimumab. The company responded to the criticism by stating that clinical experts considered the matched cohort to be clinically reflective of the UK SLE population when compared with the BR. When the ERG compared disease severity between the populations of the BILAG-BR and the matched participants of the BLISS-75 US LTE, the SS scores showed substantial differences. Contrary to the company opinion, generalisability to the UK SLE population may thus still be questionable.

-

(b)

The pre-calibration model implemented in TA397 already adjusted the baseline SS score observed in the Johns Hopkins cohort upwards to match that of the BLISS trials. The addition of a second adjustment was insufficiently justified.

-

(c)

The company derived the calibration factor by using the overall modelled belimumab population, while it should have calibrated only responders in the belimumab arm of the model to the BLISS LTE study cohort (which included only responders). In response, the company conducted a scenario analysis where the calibration factor was derived based on belimumab responders only. This scenario analysis did not increase the ICER substantially; however, this scenario did not fully reflect the issue as the company continued to assume equal disease activity reduction at 52 weeks for belimumab non-responders and patients in the ST arm. This was not in line with evidence from the BLISS trials.

-

(d)

The model was calibrated to only match the results of the PSM for the time point of 6.5 years into the modelled time horizon, i.e. 5-year data of the PSM. This meant that the calibration overestimated the reduction in organ damage belimumab could achieve according to the PSM in years 2, 3 and 4 into the modelled time horizon.

In conclusion, the ERG considered the use of the calibration factor inappropriate. Due to limitations around the PSM and the methods used for the calibration, the accuracy of long-term organ damage estimates was likely not improved and additional bias may have been introduced.

4.1.4 Uncertainty About the Continued Beneficial Effect of Belimumab on Non-Responding Patients

Response was estimated at baseline in the model and was not linked to modelled improvement in the SS score. SS scores were estimated based on a regression model where response was an independent variable. Disease activity and response were therefore estimated independently. As a result, 46.5% of the modelled patients were classified as non-responders, but nevertheless experienced a response (> 4 points in reduction in SS score) at 52 weeks. These patients in the model would no longer incur belimumab costs but would have improved SS scores, thereby biasing model outcomes in favour of belimumab. The company disagreed with this issue and responded that depending on SS baseline score, belimumab non-responders at week 24 could conceivably experience a reduction of > 4 points on the SS score at week 52. The ERG asked the company to provide evidence that it is only the chronology of events that caused belimumab non-responders to have a > 4-point reduction in SS scores at 52 weeks, with which the company did not comply. The issue remained unresolved.

4.1.5 Assumption that Belimumab Non-Responders Have the Same SELENA-SLEDAI Score at 1 year as Patients Treated with Standard Treatment

In the model, belimumab non-responders had the same disease activity reduction at 52 weeks as patients in the ST arm, who, according to evidence from the BLISS trials, would actually experience a larger disease activity reduction than belimumab non-responders. This was caused by an error in the programming, which reassigned belimumab non-responders to the modelled ST arm before estimating their disease activity. The ERG fixed this error in the model, but in response, the company stated that their approach had been deliberate, although in disagreement with their report, to reflect that belimumab non-responders would subsequently receive ST. The ERG criticised that the model did not capture any disadvantage from being a non-responder and was not in line with evidence from the BLISS trial. The issue was corrected in the ERG base-case but the company maintained their base-case, which meant that estimation of organ damage using the calibration factor may have been biased.

4.1.6 Correct Application of the General Utility Equation

The ERG identified an error in the utility model used. The coefficients used were taken from a model that also included other covariates accounting for organ damage; however, these covariates were excluded without re-estimating the other coefficients. The company agreed. However, due to time constraints, the company conducted scenario analyses varying regression utility coefficients by one standard deviation in each direction, which increased and decreased the ICER by £3000/QALY, with single coefficients varied. The ERG recommended that this uncertainty be considered in decision making.

4.1.7 Application of Organ Damage Multipliers

There was concern that using individual organ damage utility multipliers may overestimate the impact of organ damage on patients’ HRQoL. The company attempted to mitigate this by only using one utility multiplier even where more than one organ had been damaged. A scenario analysis conducted by the ERG excluding the organ damage multipliers increased the ICER as some of the modelled benefit of belimumab was reduced.

4.2 Additional Work Undertaken by the ERG

Based on all considerations highlighted in the ERG critique, the ERG defined a new base-case in which various adjustments were made to the company’s base-case. For the ERG base-case this included:

-

fixing the error related to the reduction in SS for belimumab non-responders;

-

removing the calibration factor.

The ERG’s base-case including the PAS resulted in an ICER of £30,278 and £29,313 for the intravenous and subcutaneous populations, respectively.

For additional scenario analyses the ERG implemented the following changes:

-

to analyse the uncertainty surrounding scenario analyses:

-

o

use of the unadjusted Johns Hopkins model;

-

o

use of the company’s calibration factor;

-

o

use of the calibration factor on both treatment arms.

-

o

-

removing the utility multipliers to explore the overall impact of organ damage;

-

the use of patient weight based on trial populations instead of the BILAG-BR;

-

application of the HDA-1 subgroup instead of the HDA-2 subgroup.

4.3 Conclusions of the ERG Report and Technical Engagement

The company’s health economic model mostly addressed the scope, except for two comparators being excluded. The company provided justification for excluding those comparators and the ERG agreed that it would have been challenging to model the comparison with rituximab and that cyclophosphamide may not be an appropriate comparator. The company’s cost-effectiveness estimates rest on assumptions surrounding long-term treatment effectiveness and impact on organ damage. The resulting uncertainty was not resolved with additional evidence and modelling. The ERG did not consider the application of the calibration factor to be appropriate. Cost-effectiveness estimates of belimumab compared with ST were uncertain and likely biased. Even when the modelling issues were addressed, substantial uncertainty remained about the long-term treatment effectiveness of belimumab.

5 Key Methodological Issues

A major problem with this appraisal is the lack of comparison with rituximab. The reason for this seems to be that NHS England, by their commissioning policy, effectively recommended belimumab instead of rituximab, reserving rituximab for second-line treatment, even though NICE had previously determined there was insufficient evidence to make this decision. This led to a lack of comparability between those patients who received rituximab and those who received belimumab in the BILAG-BR.

The company applied a calibration factor for two reasons. First, the PSM showed a larger difference in organ damage between belimumab and standard of care compared with the company’s original model. Second, baseline disease activity was lower in the TLC cohort than in the BLISS-LTE. However, because the PSM and TLC were not clearly superior in terms of their generalisability to the decision problem, the ERG was not convinced that the calibration was indicated. Notably, the model calibration exercise suffered from incompatible data (1) as described above, the PSM was biased, as it was likely that most patients remaining in the BLISS LTE had a positive response to belimumab; (2) there were population differences as both populations used for the PSM were North American; and (3) possible healthcare setting differences, again because both populations used for the PSM were North American.

Apart from these issues with data incompatibility, there were also issues with how the calibration was implemented. In the following points, we would like to propose steps that could have been taken to improve the calibration approach taken by the company.

-

Uncertainty should have been considered in the calibration exercise, for example by using Bayesian methods for external validation, as proposed by Corro Ramos et al. [25]. The method calibrates a model towards predetermined accuracy intervals instead of using one single point estimate. The resulting model is then evaluated by calculating the percentage of iterations of a probabilistic analysis that fall into the predetermined accuracy interval. The result would be a calibration factor with CIs that would reflect the quantified uncertainty in the PSM. Conducting the calibration in the highlighted manner would have allowed for the quantified uncertainty to be reflected in the results and additional analyses of the model.

-

The calibration was conducted to a single time point. This may be inappropriate as deviations from the average over time may have greatly influenced the outcomes of the calibration. Instead of calibrating the SDI score to a single time point, as was done in the company’s model, data could have been calibrated to the SDI score over time. This would have given a more accurate reflection of the change over time in SDI score in the model (e.g. potentially through annual calibration of the SDI).

-

Guidance suggests that the quality of evidence that informs a calibration exercise should be as high as possible [26]. In the case of this model, the latest measurement point of the BLISS LTE was used. This measurement point is likely biased due to the constraints of the long-term extension study used for the PSM. A calibration based on evidence of higher quality would therefore have been preferable. Calibrating to earlier measurement points may have hence been more adequate.

-

Mandrik et al. [27] propose the down-weighting of calibration targets with higher uncertainty. To avoid using arbitrary weights, these could be informed by expert elicitation. In this case, that would mean that instead of calibrating completely towards the PSM, experts would evaluate the trust we should put into the results of the PSM.

6 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidance

6.1 Consideration of Clinical Effectiveness

The NICE AC agreed that some of the issues raised in the ERG report had been resolved after technical engagement. These included the fact that there is no evidence for using belimumab in patients with severe active CNS lupus, that cyclophosphamide is not a relevant comparator, and that intravenous and subcutaneous formulations of belimumab are likely to be clinically comparable. In addition, the NICE AC concluded that the company’s updated population (HDA-2 subgroup) was appropriate for decision making.

The FAD stated “The committee heard that, if belimumab is not recommended for routine commissioning, more people would potentially have treatment with rituximab in its absence” (page 7). It therefore concluded that rituximab was still a relevant comparator [2].

The NICE AC noted that the long-term extension studies did not have comparator arms. It concluded that they did not provide long-term effectiveness evidence for belimumab compared with ST. In addition, the NICE AC concluded that the uncertainty about the relative clinical- and cost-effectiveness of belimumab and rituximab remains and should have been explored by the company using the BILAG-BR substudy.

The NICE AC discussed how the two cohorts used in the PSM analysis were from the US and Canada. Because of this, the NICE AC considered that there was uncertainty in the generalisability of the treatment effect observed in the analysis to the target population who would take belimumab in England. The NICE AC concluded that the results of the propensity score-matched analysis may not be relevant to NHS clinical practice. In addition, the NICE AC concluded that the results of the propensity score-matched analysis are likely biased in favour of belimumab.

6.2 Consideration of Cost Effectiveness

With regard to the application of the calibration factor, the NICE AC stated that they understood why the calibration factor had been applied but that concerns about the methodology remained. Based on the ERG critique, the NICE AC concluded that the company’s calibration factor to adjust for long-term organ damage was not suitable for decision making.

The NICE AC did not think it was clinically plausible that nearly half of these modelled ‘non-responders’ (46.5%) would have had an SS score reduction of 4 or more at 52 weeks after reverting to ST alone at 24 weeks [2]. It further considered that a 6-month cycle length may have been more appropriate to use in the model to align with the 24-week continuation rule. It remained unclear whether the modelled response to treatment for belimumab ‘non-responders’ was consistent with the BLISS trials.

Regarding the error that the ERG highlighted, with ‘non-responders’ having equal SS scores as responders after 1 year, the NICE AC noted that the impact of all conducted scenario analyses by the company on the ICER were small. It further discussed the ERG’s base-case, which used the BLISS evidence to incorporate the difference in disease activity between ‘non-responders’ and patients having ST in the first 52 weeks. The NICE AC preferred the ERG’s approach and concluded that disease activity for patients whose condition has not responded to belimumab should be based on the BLISS trials for the first 52 weeks.

The NICE AC agreed with the ERG that there was still uncertainty around the effect of the error in utility estimation on the cost-effectiveness results (Section 3.4.6). Instead of the scenario analysis in which all regression coefficients were varied by one standard deviation, the NICE AC would have preferred the company to provide a re-estimated model to resolve the uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness results.

The NICE AC considered that the most plausible ICERs for belimumab compared with ST would likely fall in between the company’s and ERG’s base-case deterministic ICERs. Therefore, it considered that both formulations of belimumab would be a cost-effective use of NHS resources.

7 Conclusions

In this review of TA397, the NICE AC recommended belimumab as an add-on treatment option for active autoantibody-positive SLE in the HDA-2 subgroup, in both intravenous and subcutaneous formulations, for routine commissioning. This decision was taken because the existing evidence suggested that belimumab plus ST reduced disease activity more than ST alone. A comparison with rituximab in the original TA397 was and still is lacking. Furthermore, the long-term effects and cost-effectiveness estimates remain uncertain due to the limited duration of existing trials.

Change history

04 September 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-023-01315-1

References

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Belimumab for the treatment of active autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus (review of TA397) [ID1591]: Committee Papers. London: NICE; 2021.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Final appraisal document: Belimumab for treating active autoantibody positive systemic lupus erythematosus. London: NICE; 2021.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Belimumab for the treatment of active autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus (review of TA397): Final scope. London: NICE; 2020.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Belimumab for the treatment of active autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus (review of TA397) [ID1591]. London: NICE; 2016.

GlaxoSmithKline. Belimumab for treating active autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus [ID1591] – Response to request for clarification from the ERG: GlaxoSmithKline; 2020.

GlaxoSmithKline. Belimumab for treating active autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus [ID1591]: Submission to National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Single technology appraisal (STA): Document B – Company evidence submission. GlaxoSmithKline; 2020.

Pearce FA, Rutter M, Sandhu R, Batten RL, Garner R, Little J, et al. BSR guideline on the management of adults with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) 2018: baseline multi-centre audit in the UK. Rheumatol (Oxf). 2021;60(3):1480–90.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Final appraisal determination—Belimumab for treating active autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus. London: NICE; 2016.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Belimumab for the treatment of active autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus: FAD committee papers [ID416/TA397]. London: NICE; 2013.

Gordon C, Amissah-Arthur MB, Gayed M, Brown S, Bruce IN, D’Cruz D, et al. The British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Rheumatol (Oxf). 2018;57(1):e1–45.

GlaxoSmithKline. A phase 3, multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 52-week study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of belimumab (HGS1006, LymphoStat-B™), a fully human monoclonal anti-BLyS antibody, in subjects with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [data on file]. GlaxoSmithKline; 21 Jan 2010.

Navarra SV, Guzmán RM, Gallacher AE, Hall S, Levy RA, Jimenez RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9767):721–31.

GlaxoSmithKline. A phase 3, multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 76-week study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of belimumab (HGS1006, LymphoStat-B™), a Fully human monoclonal anti-BLyS antibody, in subjects with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [data on file]. GlaxoSmithKline; 2010.

Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, Cervera R, Wallace DJ, Tegzová D, et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(12):3918–30.

GlaxoSmithKline. Clinical Study Report: A phase 3, multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 52-week study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of belimumab (HGS1006) administered subcutaneously (SC) to subjects with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—double-blind endpoint analysis [data on file]. GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

Doria A, Stohl W, Schwarting A, Okada M, Scheinberg M, van Vollenhoven R, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous belimumab in anti-double-stranded DNA-positive, hypocomplementemic patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(8):1256–64.

GlaxoSmithKline. A multi-center, continuation trial of belimumab (HGS1006, LymphoStat-B), a fully human monoclonal anti-BLyS antibody, in subjects with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who completed the phase 3 protocol HGS1006-C1056 or HGS1006-C1057 [data on file]. GlaxoSmithKline; 2017.

GlaxoSmithKline. A multi-center, continuation trial of belimumab (HGS1006, LymphoStat-B), a fully human monoclonal anti-BLyS antibody, in subjects with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who completed the phase 3 protocol HGS1006-C1056 in the United States [data on file]. GlaxoSmithKline; 2015.

GlaxoSmithKline. A phase 3, multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, 52-week study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of belimumab (HGS1006) administered subcutaneously (SC) to subjects with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—open-label phase—end of study report [data on file]. GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

van Vollenhoven RF, Navarra SV, Levy RA, Thomas M, Heath A, Lustine T, et al. Long-term safety and limited organ damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus treated with belimumab: a phase III study extension. Rheumatol (Oxf). 2020;59(2):281–91.

Urowitz MB, Ohsfeldt RL, Wielage RC, Kelton KA, Asukai Y, Ramachandran S. Organ damage in patients treated with belimumab versus standard of care: a propensity score-matched comparative analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(3):372–9.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Belimumab for treating active autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus [TA397]. London: NICE; 2016.

GlaxoSmithKline. Reporting and analysis plan (RAP) for the UK Benlysta prospective, observational BILAG British Registry (BILAG-BR) sub-study [data on file]. GlaxoSmithKline; 2020.

Wallace DJ, Ginzler EM, Merrill JT, Furie RA, Stohl W, Chatham WW, et al. Safety and efficacy of belimumab plus standard therapy for up to thirteen years in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(7):1125–34.

Corro Ramos I, van Voorn GAK, Vemer P, Feenstra TL, Al MJ. A new statistical method to determine the degree of validity of health economic model outcomes against empirical data. Value Health. 2017;20(8):1041–7.

Dahabreh I, Chan J, Earley A, et al. Chapter 4: a review of validation and calibration methods for health care modeling and simulation. Modeling and simulation in the context of health technology assessment: review of existing guidance, future research needs, and validity assessment. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017.

Mandrik O, Thomas C, Whyte S, Chilcott J. Calibrating natural history of cancer models in the presence of data incompatibility: problems and solutions. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022;40(4):359–66.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Author contributions

All authors have commented on the submitted manuscript and have given their approval for the final version to be published. RR, NA, LS and JK critiqued the clinical-effectiveness data reported and the literature search conducted by the company. CG provided clinical expert opinion on all aspects of this appraisal. SG, BW, BR, TO and MJ critiqued the mathematical model provided and the cost-effectiveness analyses submitted by the company. TO acts as overall guarantor for the article.

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Programme. Please visit the HTA programme website for further project information (https://www.nihr.ac.uk/funding-and-support/funding-for-research-studies/funding-programmes/health-technologyassessment).

Conflicts of interest

Caroline Gordon co-authored a grant for the Beat-Lupus Trial, funded by Versus Arthritis, with Principal Investigator (PI) Michael Ehrenstein at University College London, which assessed belimumab (from GSK) after rituximab in SLE, but received no funding herself. Thomas Otten, Rob Riemsma, Ben Wijnen, Nigel Armstrong, Lisa Stirk, Bram Ramaekers, Jos Kleijnen, Manuela Joore, and Sabine Grimm have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design and all authors were involved with the work of the ERG. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Thomas Otten and all authors had the chance to comment on previous versions of the manuscript. The author contributions for each author are described in the attached authorship forms.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised to include the complete text under Section 2 in the article PDF.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Otten, T., Riemsma, R., Wijnen, B. et al. Belimumab for Treating Active Autoantibody-Positive Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: An Evidence Review Group Perspective of a NICE Single Technology Appraisal. PharmacoEconomics 40, 851–861 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01166-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01166-2