Abstract

Objectives

Mental and behavioural disorders (MBDs) and interventions targeting MBDs lead to costs and cost savings in the healthcare sector, but also in other sectors. The latter are referred to as intersectoral costs and benefits (ICBs). Interventions targeting MBDs often lead to ICBs in the education and criminal justice sectors, yet these are rarely included in economic evaluations. This study aimed to investigate the attitudes held by health economists and health technology assessment experts towards education and criminal justice ICBs in economic evaluations and to quantify the relative importance of these ICBs in the context of MBDs.

Methods

An online survey containing open-ended questions and two best–worst scaling object case studies was conducted in order to prioritise a list of 20 education ICBs and 20 criminal justice ICBs. Mean relative importance scores for each ICB were generated using hierarchical Bayes analysis.

Results

Thirty-nine experts completed the survey. The majority of the respondents (68%) reported that ICBs were relevant, but only a few (32%) included them in economic evaluations. The most important education ICBs were “special education school attendance”, “absenteeism from school”, and “reduced school attainment”. The most important criminal justice ICBs were “decreased chance of committing a crime as a consequence/effect of mental health programmes/interventions”, “jail and prison expenditures”, and “long-term pain and suffering of victims/victimisation”.

Conclusions

This study identified the most important education and criminal justice ICBs for economic evaluations of interventions targeting MBDs and suggests that it could be relevant to include these ICBs in economic evaluations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mental and behavioural disorders (MBDs) impact not only the healthcare sector, but also education and criminal justice sectors. However, the costs and/or benefits of MDBs in these sectors are rarely incorporated in economic evaluations of MBD interventions. Furthermore, little is known about what costs and benefits are the most important for inclusion in economic evaluations. |

This study provides a ranking of the most important costs and benefits in the education and criminal justice sectors with regard to MBDs. This could help researchers select the most relevant cost items for economic evaluations of interventions targeting MBDs. Furthermore, although the respondents agreed that education and criminal justice costs and benefits could be relevant, only a few had previously included them in economic evaluations. |

Few pharmacoeconomic guidelines support the inclusion of education and criminal justice costs and benefits in economic evaluations. This indicates the need to revise the current guidelines and to stimulate further methodological research to facilitate the inclusion of education and criminal justice costs and benefits in economic evaluations of MBD interventions, thus providing improved evidence for policy decision-making. |

1 Introduction

Mental and behavioural disorders (MBDs) are estimated to affect more than one in six people during their lifetime, making them one of the top public health challenges worldwide [1, 2]. These disorders are associated with impaired capabilities in personal, familial, and social functional areas and may adversely affect one’s ability to actively participate in society [3]. Up to 50% of the economic burden of MBDs is reflected in indirect costs to the labour market, due to the lower productivity associated with MBDs and overall impact on economic growth [1, 4]. Furthermore, MBDs are associated with reduced educational attainment [5] and increased likelihood of contact with the justice system [6]. The cost of supporting individuals with MBDs can be far higher than for their peers, as they often require additional support to achieve the same educational outcomes and increasingly engage in risky behaviour and criminal activity [7]. This is further supported by the evidence from several cost of illness studies of MBDs, which demonstrate that the costs of these disorders that fall on the education and criminal justice sectors can be significant [8, 9]. Hence, effective health interventions for MBDs can result in cost savings, i.e. benefits, in these sectors.

Costs and benefits attributable to the implementation of health interventions but that occur in sectors outside the healthcare sector are referred to as intersectoral costs and benefits (ICBs). Within this concept, benefits can be best described as prevented costs, i.e. cost savings that can be associated with lower resource use, improved outcomes, and/or averted consequences. From a welfarist theoretical framework, which focuses on maximising societal well-being and underlies the definition of a societal perspective, all costs and benefits engendered by an intervention should be included in economic evaluations regardless of on whom they fall [11]. Therefore, considering that interventions targeting MBDs are expected to generate ICBs in the education and criminal justice sectors [12], it is necessary to account for them when conducting economic evaluations. Failure to include relevant ICBs in an economic evaluation might lead to suboptimal and misinformed decision-making [13].

The inclusion of education and criminal justice ICBs in economic evaluations is supported by several national pharmacoeconomic guidelines [14,15,16]. Furthermore, several studies investigated the identification, measurement, and valuation of education and criminal justice ICBs in health economics research [10, 17, 18]. Nevertheless, to date, few economic evaluations incorporate these ICBs, even though they might be relevant to the study context [19, 20]. This can be due not only to the scarcity of validated methods and tools to measure and value education and criminal justice ICBs, but also to the lack of resources to collect data and the lack of knowledge about the relevance of ICBs and which ICBs are the most important to include in economic evaluations. Furthermore, national policy guidelines do not always recommend adopting a societal perspective.

Although an overview of relevant education and criminal justice ICBs does exist [10], it does not provide guidance in terms of which ICBs are the most important to include in economic evaluations. Mayer et al. [18] developed a list of the most common education and criminal justice ICBs, based on the existing health-related resource-use measurement instruments. While this list could help us to gain insight into the importance of these ICBs, it does not provide a ranking. To date, no research has focused on investigating the relative importance of education and criminal justice ICBs in economic evaluations. Given that this knowledge would be particularly valuable for health economists and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) experts conducting economic evaluations in the MBD domain and for researchers undertaking further methodological research in the field of ICBs, the aim of this study was to assess the relative importance of the education and criminal justice ICBs that are of importance for economic evaluations in the disease area of MBDs among health economists and HTA experts, using best–worst scaling (BWS). Furthermore, this study aimed to gain insight into the experts’ attitudes towards and experiences with including ICBs in economic evaluations.

2 Methods

2.1 Best–Worst Scaling

BWS is a survey method for assessing an individual’s priorities or preferences for a set of attributes [21]. A BWS object case, a type of BWS survey method, identifies the relative values associated with each of the attributes on a master attribute list.

Two BWS object case surveys (one for education and one for criminal justice) were conducted to obtain experts’ preferences with regard to the most important education and criminal justice ICBs for inclusion in economic evaluations conducted from a societal perspective in the disease area of MBDs. The Checklist for Conjoint Analysis Applications in Health from the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) was followed to design and conduct the BWS survey and to report the results of the study [22].

2.2 Identification of the Attributes

Prior to the BWS object case surveys, a mutually exclusive attribute list was generated using a two-stage procedure. A mutually exclusive attribute list is essential for obtaining valid outcomes in BWS analysis [23]. First, potential attributes were extracted by one researcher (LB) from earlier research on ICBs [10, 18] and resource-use measurement instruments, via a hand search of the Database of Instruments for Resource Use Measurement (DIRUM) [24]. Second, the attributes were compiled and clustered based on similarity using the classification of Drost et al. [10] as a reference. Third, the list of attributes was defined and validated in a working group of five co-authors with expertise in the field of ICBs (IP, LJ, RD, AP, and LB) to ensure completeness and mutual exclusivity. This resulted in the final list of 20 education ICBs and 20 criminal justice ICBs (i.e. attributes) to be assessed in the BWS survey (Supplementary File 1, see the electronic supplementary material). It is important to note that every attribute could be viewed both as a cost and as a benefit (i.e. cost saving or improved outcome).

2.3 Survey Respondents

Health economists and HTA experts were chosen as the target group for this study because they are involved in the selection of relevant costs and benefits for the inclusion in economic evaluations. Convenience and snowball sampling methods were used to recruit respondents. Experts were screened for inclusion based on a question integrated in the survey, which assessed whether they had work experience in the field of health economics in general and experience with conducting health economic evaluations. Respondents who reported having no work experience in the field of health economics were redirected to the end of the survey. Respondents with experience in health economics but with no specific experience in economic evaluations were assumed to have sufficient knowledge to participate in the study. Potential respondents were approached at several health economics and HTA conferences between May and November 2019. In addition, targeted e-mails were sent to potentially eligible experts. Respondents were asked to invite and/or provide contact information of colleagues who would be interested in completing the survey. Social media promotion was also employed. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Hospital Maastricht and Maastricht University, the Netherlands (approval number FHML-REC/2019/030). All respondents provided informed consent prior to completing the survey, and they were free to stop participation at any moment.

2.4 BWS Survey

The experimental design of the BWS object case surveys was developed using Sawtooth Software’s SSI Web platform, resulting in fractional and efficient designs, which are characterised by orthogonality, minimal overlap, positional balance, connectivity, and stability. To improve statistical efficiency, two different versions of the questionnaire were generated per object case survey, i.e. two versions for education and two versions for criminal justice. Each version contained 12 education and 12 criminal justice choice sets with five attributes per choice set. Each attribute was presented 12 times, was combined at least once with every other cost and benefit, and appeared two to four times in each position in the choice set. Definitions were provided alongside each choice set as recommended by good research practice guidelines [22]. For each choice set, respondents were asked to select which cost and benefit was the most and least important to include in economic evaluations in the disease area of MBDs. An example choice set is presented in Fig. 1.

The online survey was designed in the form of a self-administered questionnaire using Qualtrics® [25]. Respondents were randomly allocated to one of the two versions of the education ICBs object case surveys and one of the two versions of the criminal justice ICBs object case surveys. In addition to the choice sets, respondents were asked to answer questions about their professional characteristics.

The survey also contained six questions to investigate experts’ attitudes towards and experiences with including ICBs in economic evaluations. The experts were asked to indicate whether they thought including education and criminal justice ICBs in economic evaluations could be relevant and to detail the motivation behind their response. The experts were also asked whether they had previously included education and/or criminal justice ICBs in economic evaluations. At the end of each BWS object case study, respondents had the opportunity to report any additional education and criminal justice ICBs that they thought were missing from the master attribute list. Furthermore, respondents were asked to rate the difficulty of the choice tasks using a Likert scale (0 = easy to 10 = difficult). The questionnaire was piloted among health economists (n = 2), a researcher (n = 1), and health economics students (n = 2) from Maastricht University. The estimated time to complete the questionnaire was 15 min. The paper–pencil version of the questionnaire is available in Supplementary File 2 (see the electronic supplementary material).

2.5 Data analysis

First, descriptive statistics were used to generate the respondents’ professional characteristics, whether they found ICBs relevant and whether they had previously included ICBs in economic evaluations. Second, a Fischer’s exact test was employed to test the association between the respondents’ professional characteristics and whether they found ICBs relevant and had previously included them in economic evaluations. Two separate subgroup analyses were performed: those respondents with the number of years of experience in health economics below the mean were compared with the respondents with the number of years of experience equal to or above the mean; respondents employed in the Netherlands were compared with respondents employed elsewhere. In addition, respondents’ open-ended answers concerning the relevance of and previous experiences with including ICBs in economic evaluations were summarised to identify common themes. SPSS for Windows V.25 was used to perform statistical analysis; p < 0.025 was considered statistically significant.

Third, Sawtooth SSI Web version 8.2.0 was used to perform a hierarchical Bayes estimation and to calculate the mean relative importance score (RIS) for each attribute. Rescaled scores were estimated based on the raw coefficient of the preference function. These scores represent the probability that the respondent chooses a selected attribute over other attributes. The RISs for each individual cost and benefit add up to 100, with a higher score indicating a higher relative importance for that attribute [26]. An individual fit statistic was employed to examine the quality of the responses. Responses with an individual fit statistic lower than 0.25, indicating that the answers were likely to be provided at random [27], were excluded from the analysis.

Fourth, the RISs of education and criminal justice object case studies were calculated separately for the groups of respondents, based on their years of experience in health economics (i.e. below and above the mean) and country of employment (i.e. experts employed in the Netherlands vs experts employed elsewhere).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

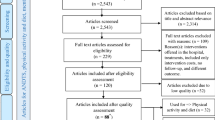

The survey was accessed 70 times between May 2019 and October 2019. In total, 39 health economists and HTA experts completed the questionnaire (response rate of 56%). Over half of the respondents (n = 23, 59%) reported being employed in the Netherlands. The respondents had on average 7.1 years (SD = 5.3) of experience in the field of health economics, and the majority (85%) reported having conducted economic evaluations prior to completing the survey. The descriptive statistics of the respondents are presented in Table 1.

Thirty-nine respondents completed the BWS object survey for criminal justice and 35 out of these 39 completed the BWS object case survey for education. The overall fit statistic was 0.47 (SD = 0.09) for the criminal justice object case survey and 0.45 (SD = 0.07) for the education object case survey. Three responses had an individual fit statistic below 0.25 (n = 2 for the education survey; n = 1 for both the education and criminal justice surveys) and were excluded from the BWS analysis. The average difficulty of the questionnaire was 7 (SD = 1.8) on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = very easy to 10 = very difficult).

4 Attitudes and Experiences of Including ICBs in Economic Evaluations

Criminal justice and education ICBs were found relevant for inclusion in economic evaluations by 29 and 31 respondents, respectively (Table 1). The majority of the respondents who found ICBs relevant had never included them in economic evaluations (68%) (Supplementary File 3, see the electronic supplementary material). No significant differences were found between the subgroups of the respondents based on their years of experience in health economics and their country of employment in relation to their opinions regarding the relevance of the ICBs and their experience with including them in economic evaluations (Supplementary File 4).

Thirty-four experts answered the open-ended questions regarding the general relevance of education and criminal justice ICBs for economic evaluations. The experts agreed that the relevance of these ICBs is dependent on the intervention/disease, the target group, and the budget holder. Several arguments in favour of including these ICBs in economic evaluations conducted from a societal perspective were mentioned. First, the definition of the societal perspective implies the inclusion of all relevant costs and benefits associated with the intervention. Second, education and criminal justice ICBs can constitute a significant proportion of the total costs and influence the results; hence, by not incorporating them in the study, the risk of bias is increased. Third, including these ICBs can demonstrate the wider impact of interventions. The reasons for not including education and criminal justice ICBs in economic evaluations were the irrelevance of these costs and benefits to the budget holder, the difficulty of obtaining information, the difficulty of quantifying these ICBs, and the difficulty of defining the boundaries of a broader (societal) perspective. Furthermore, one expert mentioned that while it is important to quantify the impact of diseases/health interventions on the education sector, the impact of educational decisions on the healthcare sector also ought to be quantified.

4.1 BWS Analysis: Education ICBs

Figure 2 illustrates the RISs and the confidence intervals of the education attributes. The most important education ICBs were “special education school attendance” (RIS = 11.21), “absenteeism from school” (RIS = 10.08), “reduced school attainment” (RIS = 9.43), “additional education services provided at a regular school outside operating hours” (RIS = 7.49), and “reduced school performance” (RIS = 7.44). The five least important education ICBs were “student transport to school” (RIS = 3), “reduced school engagement” (RIS = 2.8), “reduced school adaption” (RIS = 2.54), “attendance officer” (RIS = 1.6), and “home education/homeschooling” (RIS = 0.91). The scores and the confidence intervals of the education attributes are presented in Supplementary File 5.

4.2 BWS Analysis: Criminal Justice ICBs

Figure 3 illustrates the RISs and the confidence intervals of the criminal justice attributes. The most important criminal justice ICBs were “decreased chance of committing a crime as a consequence/effect of mental health programmes/interventions” (RIS = 12.94), “jail and prison expenditures” (RIS = 10.88), “long-term pain and suffering of victims/victimisation” (RIS = 9.94), “short-term pain and suffering of victims/victimisation” (RIS = 8.59), and “long-term pain and suffering of others” (RIS = 7.21). The five least important criminal justice ICBs were “illegal untaxed income of the offender” (RIS = 2.73), “property loss of offender” (RIS = 2.3), “lost freedom of the offender” (RIS = 1.1), “fire and rescue services” (RIS = 0.86), and “forensic services” (RIS = 0.78). The scores and the confidence intervals are presented in Supplementary File 5.

4.3 BWS Analysis: Subgroup Analysis

The RIS per attribute of two expert subgroups, one with years of experience above 7.1 (the mean number of years of experience in health economics among the respondents in this study) and the other below or equal to 7.1 were compared. In addition, the differences in the RISs per attribute were explored in relation to the country of employment of the experts (the Netherlands vs elsewhere). Subgroup analysis did not reveal notable differences in the ranking (Supplementary File 6).

4.4 Missing Attributes

Three experts reported three additional criminal justice ICBs that they thought were missing from the attribute list: “long-term effects for the offenders after release”, “income earned while in prison”, and “additional benefits/entitlements to family members/third parties (of/to victims)”. Two experts reported additional education ICBs that could be added to the attribute list: “dropout”, “costs of training teachers”, “costs of adapting facilities”, and “out-of-pocket payments for education beyond standard home schooling”.

5 Discussion

The economic impact of MBDs is substantial and affects many societal sectors, including the education and the criminal justice sectors [5,6,7]. Nevertheless, economic evaluations in the area of MBDs rarely capture this impact, which can be attributed to the lack of knowledge about the relevance of ICBs and which ICBs are the most important to include in economic evaluations. This study, using data obtained from an online survey, provides insight into health economists’ and HTA experts’ opinions about and experiences with the inclusion of education and criminal justice ICBs in economic evaluations. Furthermore, BWS was employed to assess the relative importance of these ICBs, to help researchers in selecting the most important ICBs for inclusion in economic evaluations of MBDs. Thirty-nine experts participated in the survey and assessed the relative importance of the education and criminal justice ICBs in a BWS experiment.

While the majority of the respondents agreed that education and criminal justice ICBs could be relevant for economic evaluations, far fewer of them reported having previously included these ICBs in economic evaluations. This could be attributed to the experts’ focus on a disease area for which education and criminal justice ICBs are less important (e.g. palliative care). Furthermore, national pharmacoeconomic guidelines play an important role in framing economic evaluations in a given country. Of the participating experts’ countries of employment, only the Dutch guidelines specifically recommend the inclusion of education and criminal justice ICBs if these are relevant to the context of the study [14], whereas other national guidelines recommend either a healthcare system perspective or a societal perspective without specifying education or criminal justice ICBs [28]. Therefore, to facilitate the adoption of a broader societal perspective in economic evaluations, a re-examination of existing national pharmacoeconomic guidelines is needed, in addition to further methodological developments. Furthermore, the adoption of a societal perspective does not preclude conducting additional analyses from narrower healthcare or payer perspectives as these costs would already be available for the analysis.

While various arguments have been put forward as to why a societal perspective could be considered superior to narrower healthcare and payer perspectives [13], choosing a broader perspective has implications for the funding of new healthcare interventions. Health interventions are generally subsidised by the healthcare sector alone, and policy silos currently hinder effective intersectoral coordination and efficient use of resources to enhance societal welfare and improve population health [29]. If an intervention delivers benefits in sectors outside healthcare, it is imperative to consider the possibility of multisectoral funding. This highlights the growing importance of broader integrated approaches to policy-making, in particular in relation to health, such as Health in All Policies, which emphasise intersectoral accountability and joint funding [30, 31]. Furthermore, research that demonstrates the intersectoral benefits of health interventions could act as a catalyst for setting up such initiatives.

The most common education ICBs in resource-use measurement instruments, as identified by Mayer et al. [18] were “absenteeism from school”, “tutoring”, “classroom assistance”, “special school/boarding school”, and “social and school functioning”, which includes some of the most highly ranked education ICBs. However, while the items “reduced school attainment” and “reduced school performance” were considered important by the experts, these were not often included in the existing resource use measurement (RUM) instruments. The most common criminal justice ICBs were “lawyer/legal assistance”, “police custody/prison detainment”, “court appearance”, “injury”, and “police contact”, which is less comparable to the ranking in this study. Judicial services were ranked much lower in comparison with less tangible consequences of crime (e.g. “long-term pain and suffering of victims/victimisation”), with the exception of “jail and prison expenditures”. Furthermore, the attributes related to the consequences of crime for the victims were ranked more important in comparison with the consequences for the offenders. Although from a societal perspective it makes no difference where costs and benefits associated with an intervention occur, bias towards favouring victims of crime rather than offenders might lead to prioritising the costs and benefits that fall on victims rather than those that fall on offenders. This could lead to biased results, inequitable resource allocation, and loss of societal welfare (i.e. financial and productivity losses) [32]. The differences between these two lists could be due to the specific focus on MBDs, while Mayer et al. reviewed all existing RUM instruments. In addition, the most important ICBs in this study were not only resource-use items that could be measured by a self-reported questionnaire (e.g. “jail and police expenditures”), but also outcomes, which could be measured by either reviewing administrative data (e.g. “reduced school attainment”) [33] or by employing quality-of-life measurement instruments (e.g. “long-term pain and suffering of victims”).

Several experts provided additional education and criminal justice ICBs that could complement the master attribute list. Some of the suggested ICBs have been incorporated in the attributes that were already included in the attribute list. For example, the attribute “reduced school attainment” included school dropout/premature leave, refusal of admission, exemption from compulsory education, and change in the educational level. Hence, including “dropout” would compromise the mutual exclusivity of the attributes. Prior to including additional ICBs in the attribute list, an assessment of each attribute in relation to other attributes must be completed to ensure the mutual exclusivity of the attributes. Employing a group consensus method (e.g. Delphi method) [34] could allow the development of a comprehensive and mutually exclusive attribute list.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to date that aimed to evaluate the relative importance of education and criminal justice ICBs in the context of MBDs among health economists and HTA experts. Nevertheless, this study is subject to several limitations. First, despite numerous efforts to reach potential respondents, the sample size of this study was relatively small (n = 39). While sample size calculations are not required for studies using BWS methods, a sample size of 50 respondents is recommended as a rule of thumb [35]. The small sample size and the overrepresentation of Dutch respondents in the sample could limit the generalisability of the results. Second, experts were able to access the questionnaire an unlimited number of times, which means they could have started it multiple times before eventually completing it. This might have led to an overestimated non-response rate; however, due to privacy regulations, it was not possible to account for this factor when analyzing the responses. In addition, we were not able to distinguish the experts with and without experience in the MBD domain, while this could have provided additional insights into the relationship between experience in this domain and the attitudes regarding the relevance of the inclusion of ICBs in economic evaluations. Third, completing the questionnaire was rated relatively difficult (7 out of 10). This might explain why fewer respondents completed the object case survey for education (n = 35) in comparison with the object case for criminal justice (n = 39). Because the object case survey for criminal justice was completed prior to the one for education, several respondents might have quit without finishing the education survey due to survey fatigue.

The findings of this study could facilitate the inclusion of ICBs in economic evaluations in several ways. First, it could help researchers with selecting the most relevant ICBs for inclusion in economic evaluations in the area of MBDs, while limiting the burden associated with survey fatigue. It is important to note that education and criminal justice ICBs can be incorporated in economic evaluations on both the cost and the effect side. Researchers need to be aware of potential double counting [37]. Second, this could help advance methodological research into the development of measurement and valuation instruments. Furthermore, it is important to note that a general prioritisation of education and criminal justice ICBs does not provide sufficient information regarding the importance of these items in a specific context, because the importance of cost items will always be dependent on the patient population, disease, and/or intervention of interest, among other factors [36]. Using other methods, such as reviewing literature or consulting experts, might help determine the most important ICBs in a specific context. Further research could also focus on conducting a similar prioritisation exercise with other stakeholder groups (e.g. mental health professionals, policy makers, patients) to help facilitate the inclusion of relevant ICBs in economic evaluations and to contribute to preference-sensitive decision-making.

6 Conclusions

The ranking of the most important education and criminal justice ICBs identified in this study can help select relevant ICBs for developing measurement and valuation tools and for the inclusion in economic evaluations in the domain of MBDs. Furthermore, while the majority of the respondents found education and criminal justice ICBs relevant, only a few reported previously including them in economic evaluations.

References

OECD/EU. Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Paris; 2018.

Lee Y-C, Chatterton ML, Magnus A, Mohebbi M, Le LK-D, Mihalopoulos C. Cost of high prevalence mental disorders: findings from the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(12):1198–211.

WHO. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. 2018. https://icd.who.int/en. Accessed 17 Dec 2019.

Trautmann S, Rehm J, Wittchen HU. The economic costs of mental disorders. EMBO Rep. 2016;17(9):1245–9.

Esch P, Bocquet V, Pull C, Couffignal S, Lehnert T, Graas M, et al. The downward spiral of mental disorders and educational attainment: a systematic review on early school leaving. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):237.

Wallace C, Mullen PE, Burgess P, Palmer S, Ruschena D, Browne C. Serious criminal offending and mental disorder: case linkage study. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(6):477–84.

Beecham J. Annual research review: Child and adolescent mental health interventions: a review of progress in economic studies across different disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(6):714–32.

Le HH, Hodgkins P, Postma MJ, Kahle J, Sikirica V, Setyawan J, et al. Economic impact of childhood/adolescent ADHD in a European setting: the Netherlands as a reference case. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(7):587–98.

Popova S, Lange S, Burd L, Rehm J. The economic burden of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder in Canada in 2013. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2016;51(3):367–75.

Drost R, Paulus A, Ruwaard D, Evers S. Inter-sectoral costs and benefits of mental health prevention: towards a new classification scheme. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2013;16(4):179–86.

Weinstein MC, Russell LB, Gold MR, Siegel JE. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996.

O’Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE. Benefits and costs of prevention. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

Jönsson J. Ten arguments for a societal perspective in the economic evaluation of medical innovations. Eur J Health Econ. 2009;10(4):357–9.

Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Van der Linden N, Bouwmans C, Kanters T, Tan SS. Kostenhandleiding. Methodologie van kostenonderzoek en referentieprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg In opdracht van Zorginstituut Nederland Geactualiseerde versie. 2015.

HIQA. Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies in Ireland 2010. Health Information and Quality Authority; 2010.

Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, Brock DW, Feeny D, Krahn M, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093–103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.12195.

Drost RM, Paulus AT, Ruwaard D, Evers SM. Valuing inter-sectoral costs and benefits of interventions in the healthcare sector: methods for obtaining unit prices. Expert Rev Pharm Outcomes. 2017;17(1):77–84.

Mayer S, Paulus AT, Łaszewska A, Simon J, Drost RM, Ruwaard D, et al. Health-related resource-use measurement instruments for intersectoral costs and benefits in the education and criminal justice sectors. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(9):895–908.

Drost RM, van der Putten IM, Ruwaard D, Evers SM, Paulus AT. Conceptualizations of the societal perspective within economic evaluations: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017;33(2):251–60.

Kim DD, Silver MC, Kunst N, Cohen JT, Ollendorf DA, Neumann PJ. Perspective and costing in cost-effectiveness analysis, 1974–2018. Pharmaco Economics. 2020;38:1–11.

Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J. Best–worst scaling: what it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health Econ. 2007;26(1):171–89.

Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13.

Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Marley AAJ. Best-worst scaling: theory, methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015.

DIRUM. Database of instruments for resource use measurement. https://www.dirum.org/. Accessed 14 Jan 2020.

Qualtrics. Provo, Utah, USA. 2005. https://www.qualtrics.com. Accessed 13 Dec 2019.

Orme B. Hierarchical Bayes: why all the attention? Sawtooth software research paper series. 2018.

Orme B. Fit statistic and identifying random responders. In: Inc., Sequim, WA. https://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/help/lighthouse-studio/manual/hid_web_maxdiff_badrespondents.html. Accessed 27 Nov 2019.

ISPOR. Pharmacoeconomic guidelines around the world. n.a.

Froy F, Giguère S. Breaking out of policy silos. 2010.

Leppo K, Ollila E, Pena S, Wismar M, Cook S. Health in all policies-seizing opportunities, implementing policies. sosiaali-ja terveysministeriö; 2013.

Walker S, Griffin S, Asaria M, Tsuchiya A, Sculpher M. Striving for a societal perspective: a framework for economic evaluations when costs and effects fall on multiple sectors and decision makers. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17(5):577–90.

Cartwright WS. Costs of drug abuse to society. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 1999;2(3):133–4.

Bremmers LGM, Evers SMAA, Drost RMWA, Janssen LMM, Pokhilenko I, Paulus ATG. The impact of mental and behavioural disorders on resource use in the education sector: a systematic literature review. J Ment Health Policy Econ (under review).

McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):655–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x.

VanVoorhis CW, Morgan BL. Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2007;3(2):43–50.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Koopmanschap MA, van Exel NJA, van den Berg B, Brouwer WB. An overview of methods and applications to value informal care in economic evaluations of healthcare. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(4):269–80.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants involved in the pilot testing of the questionnaire and the experts who responded to the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by IP, LMMJ, and LGMB. The first draft of the manuscript was written by IP and LMMJ, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

I. Pokhilenko and L.M.M. Janssen are partially funded by the PECUNIA project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 779292.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Hospital Maastricht and Maastricht University, the Netherlands (Approval Number: FHML-REC/2019/030).

Consent to participate

All respondents provided informed consent prior to completing the survey and they were free to stop participation at any moment.

Consent for publication

All co-authors provided consent for the publication of the manuscript.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Consent

Survey participants provided informed consent prior to participation in the survey.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pokhilenko, I., Janssen, L.M.M., Hiligsmann, M. et al. The Relative Importance of Education and Criminal Justice Costs and Benefits in Economic Evaluations: A Best–Worst Scaling Experiment. PharmacoEconomics 39, 99–108 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00966-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00966-8