Abstract

Background

The measurement and valuation of health-related quality of life for and by young people are increasingly important, yet research on the impact of study perspective and validity of preferences obtained from young populations remains limited.

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and validity of collecting EQ-5D Youth version (EQ-5D-Y) preferences from adolescents, adults, and adults from a child perspective.

Methods

A profile case best–worst scaling (BWS) online survey was administered to representative Australian and Spanish adult (age ≥ 18 years) and child (age 11–17 years) samples. Adults were told to either answer from their own perspective or for a hypothetical 10-year-old child. Marginal best- and worst-choice frequencies, analysis of dominant choices, self-reported difficulty completing the tasks, and time to complete tasks were used to determine the validity of responses.

Results

In Australia, 2134 adults and 1010 adolescents completed the survey. In Spain, 2007 adults and 1000 adolescents completed it. Analysis of marginal choice frequencies and dominant choices indicated that the pattern of responses between adolescents and adults was similar. For Australian respondents, having no mobility problems was rated as best by adolescents, while adults rated having no pain and discomfort as ‘best’. In Spain, both adults and adolescents rated no pain or discomfort as ‘best’. Australian adolescents rated very worried, sad or unhappy as ‘worst’, while Spanish adolescents, Spanish adults and Australian adults rated a lot of pain and discomfort as ‘worst’.

Conclusions

Results suggest preferences from adolescents using direct BWS are valid. Our descriptive analysis also suggest that there are age-related and country-specific differences in elicitation values for the EQ-5D-Y.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Adolescents can validly value health states for the EQ-5D Youth version (EQ-5D-Y) using best–worst scaling methods. |

Adolescents and adult preferences for EQ-5D-Y dimensions vary. |

There are country-specific differences in EQ-5D-Y dimension preferences using the examples of Australia and Spain. |

1 Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is used as an input to health economic evaluation, which is increasingly used by healthcare systems around the world to make funding recommendations [1,2,3]. However, the methodological development to support measurement and valuation of HRQoL for children and adolescents has lagged behind comparable research for adults. The risk of this limitation is that there is greater uncertainty around the value of interventions in a paediatric population, and hence the possibility that children may be disadvantaged in funding decisions that utilise these measures.

A systematic review conducted by Chen and Ratcliffe [4] identified nine generic multi-attribute utility instruments (MAUIs) available internationally for use in paediatric populations. The measures differ in terms of the elicitation technique for health state valuation including standard gamble (SG), time trade-off (TTO) and best–worst scaling (BWS) [4]. When eliciting preferences for health states, different techniques are available, including cardinal techniques such as TTO and SG. More recently, ordinal methods such as discrete choice experiments (DCEs) and BWS [5] have grown in popularity due to their relative ease of comprehension, suitability for online administration and some reports of greater reliability [6, 7].

The justification for choice of valuation method has produced some unique considerations relating to the measurement of adolescents, including cognitive demand, linguistic limitations, comprehensive ability, rapid age-related differences in disease and preferences, and ethical sensitivity around presenting risk of death [8, 9]. Some have suggested that there may be differences with children’s ability to engage and produce valid results [7].

There is variation in whose preferences have been sought to score child-specific MAUIs, with only a handful of examples of direct adolescent self-valuation, including the Child Health Utility-9D (CHU-9D) using the BWS method [10,11,12], the Assessment of Quality of Life-6D (AQoL-6D) adolescent instrument using TTO valuation methods [13], and the 16-dimensional (16D) instrument using the visual analogue rating scale [14].

The choice of whose preferences to use when generating a generic preference-based measure scoring algorithm is largely a normative decision. Existing evidence indicates that adults’ preferences for identical health states may differ from adolescents’ preferences [11, 12]. When investigating CHU-9D responses, Ratcliffe and colleagues [11] found that adults place less importance relative to adolescents on impairments in mental health (worried, sad, annoyed) and more weight on moderate to severe levels of pain. This existing research comparing adult and adolescent preferences was conducted using the CHU-9D instrument and it is unknown whether this result is also valid for other child instruments such as the EQ-5D Youth version (EQ-5D-Y). The feasibility and validity of adolescent preferences is largely unknown, as is the impact of adolescent, adult proxy (adults imagining a child) and adult study perspectives on the preferences obtained for other child instruments [15, 16]. It is clear that the choice of values has important implications for utility estimation and resulting policy and practice decisions [12].

The EQ-5D is the most widely used adult preference-based instrument [17]; however, since its release in 2009, use of the EQ-5D-Y has been limited [8]. There is only one published EQ-5D-Y value set developed for the USA using a DCE and completed by adult members of the general public [18]. Further valuation exercises are underway in several countries that would allow the calculation of a utility score and enable its use in economic evaluation. While some researchers have applied the adult value set in the context of children and adolescents [9], the uncertainty about the appropriateness of this has prompted exploration of the feasibility and validity of child and adolescent direct preference elicitation [19].

Researchers have been slow to develop a scoring algorithm for the EQ-5D-Y. There has been a strong status quo for using adult preference as the normative sample and a paucity of research regarding whether adolescents’ preferences should be included [15]. In addition, we know little about how current preference elicitation methods work for children. There are concerns regarding the validity of directly eliciting adolescent preferences, and the age at which children can reliably complete valuation tasks [16]. However, previous research on the CHU-9D instrument has reported that children aged 11–17 years can complete BWS tasks [11]. Further questions involve who should value health states of children and adolescents for health policy decision making, the appropriate framing and perspective of these tasks, how to achieve consistency in the perspective across adult and adolescent valuations, and which valuation technique is feasible and appropriate when generating value sets [20].

The objective of this study is to apply profile case BWS methods to assess whether collecting information from adolescents, adults using their own perspective or adults thinking in the context of a 10-year-old child is feasible and valid in making inferences about EQ-5D-Y dimensions. To increase robustness of the findings, the work was conducted in samples of the general population in Australia and Spain.

2 Methods

2.1 Survey Design and Data Collection

An online questionnaire created in LimeSurvey (https://www.limesurvey.org/) was developed for completion in Australia and Spain. Three community-based samples in each country were obtained consisting of (1) adults responding to the BWS task from their own perspective; (2) adults responding to the BWS from the perspective of a 10-year-old child; and (3) adolescents aged 11–17 years responding to the BWS task from their own perspective (Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Supplement 1). These reflect the different perspectives used in previous research [21]. Participants were recruited via an online panel company following an invitation and providing informed consent to participate. Adolescents were recruited via a combination of direct adolescent panel membership for some adolescents aged > 14 years and via their parents who were members of the panel. The adult surveys were completed sequentially first and then a new sample of parents were approached for adolescent recruitment, resulting in independent samples with no parent/adolescent dyads. Only adult panel members who had indicated they had a child aged 11–17 years were approached for this method of adolescent recruitment.

A sample of 1000 was the target set for each study perspective in each country. Sample size methodology for BWS experiments are underdeveloped so this size was chosen based on previous experience and in order to be comparable with other similarly focused published research [11, 12].

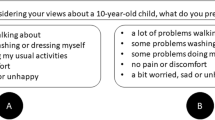

The survey comprised three main sections. The first section contained screening questions to ensure a representative sample of the Australian and Spanish general population. Representativeness was sought in terms of age, sex and geographical distribution (state in Australia or region in Spain). Respondents were then asked to self-complete the EQ-5D-Y instrument. Completing the instrument at the start of the survey ensured that respondents were familiar with its wording, structure and the range of questions before they were asked to complete the BWS task. The EQ-5D-Y includes five dimensions (mobility, looking after myself, performing usual activities, having pain/discomfort, feeling worry/sad/unhappy) and three levels (no problems, some problems, a lot of problems) defining 243 (35) separate health states [22]. Each health state that can be generated from the instrument can be expressed as a five-digit number; for example, the health state 21111 corresponds to someone with some problems in walking about, but no problems with performing usual activities, having pain/discomfort, looking after myself or feeling worried, or being sad or unhappy.

In the second survey section, respondents were presented with detailed instructions and a practice BWS question. They were then presented with a series of EQ-5D-Y health states and from these health states they were asked to indicate the best and worst attributes/dimensions from each health state presented (ESM Supplement 1). Profile BWS was chosen as the method for this study due to its cognitive simplicity and our interest in direct adolescent value elicitation down to age 11 years as used in previous studies [10]. Profiles for the BWS exercise were generated using a full factorial design (35) of the 243 health states randomly divided into 20 blocks (ESM Table 1). Each block consisted of an even number of mild, moderate and severe states, selected based on the sum of the five-digit number representing a particular health state (mild states sum of 6–9, moderate states sum of 10–12 and severe states sum of 13–15). Nineteen blocks included 13 BWS tasks with the remaining block including 14 tasks. All blocks included the state 33333. Each participant was randomised to one of the 20 blocks (minimum 4.3% of sample and maximum 9.7%; ESM Table 2).

The final survey section collected sociodemographic information such as whether the participant lived with a chronic condition along with the level of difficulty completing the survey. To identify the socioeconomic position of adolescents we included the family affluence scale (FAS) questionnaire, which can be categorised into three levels of family affluence (low, medium or high) [23]. The adult surveys included questions on marital status, whether someone with disabilities lived with the participant, educational level, employment status, occupation, whether they had been employed in a role working with children, if they had children and, if so, their children’s age.

2.2 Data Analysis

The analysis focuses on the feasibility and validity of obtaining preferences from the three samples. In addition, we also describe adolescent preferences. Measures of feasibility include survey completion and self-reported difficulty and analysis of validity based on time to complete, best–worst frequencies, marginal choice frequencies and dominant choice sets as defined in Sect. 3.4. Each analysis is performed across different years of age and across the three study perspectives (adolescents, adults, and adults from a child perspective).

Numbers of participants completing the survey from each sample were summarised for each of the three samples. The median time to complete the total survey (including consent and background information) was calculated, along with time to complete the BWS survey component. Time was calculated for each sample and by year of adolescent age. The BWS task was designed to take approximately 5 min to complete. Self-reported EQ-5D-Y responses for all samples were described by the proportion choosing ‘no problems’, ‘some problems’ or ‘a lot of problems’ in each dimension. The socioeconomic characteristics and the distribution of self-reported health of the samples were analysed using descriptive statistics including means and proportions. Responses to the BWS tasks were summarised identifying all possible best–worst pairs and marginal choice frequencies [24]. All 180 possible best–worst pairs of dimension levels and their frequency of being selected were tabulated. Marginal choice frequencies were calculated as the number of times a particular dimension level was chosen as best (or worst), divided by the number of times that level was available to be chosen as best (or worst) in the survey. Marginal choice frequencies were also graphed to indicate the spread and distribution of best and worst choices.

An additional analysis was undertaken to determine the proportion of responders in each sample who correctly selected the best or worst level for health state scenarios in which there was a ‘dominant’ best or worst health level presented, divided by the number of times that choice was presented. This occurs when there is one level 3 and four level 1 dimensions, or four level 1 and one level 3 dimensions. For example, for health state 11113, being ‘very sad/worried’ would be expected to be rated as the worst health level, as the other four levels all reflect no problems. The proportion of times chosen for each sample and by year of adolescent age are presented for the ‘dominant’ best and clear worst level health states.

Descriptive analyses were conducted exploring self-reported difficulty completing the survey, and these are presented for each sample and by year of adolescent age. Additional sensitivity analyses of the marginal choice frequencies for those reporting that the task was ‘difficult’ or ‘very difficult’ were also conducted.

3 Results

3.1 Sample and Completion Statistics

In Australia, 2134 adults (age range 18 to > 65 years, of whom 1120 answered from a child perspective) and 1010 adolescents completed the online survey. In Spain, 2007 adults (age range 18 to > 55 years, of whom 1001 answered from a child perspective) and 1000 adolescents completed the online survey. More adolescents were invited to participate in order to fill age, sex and geographic quotas, but adolescents successfully completed the survey in similar proportions to the adult samples.

Tables 1 and 2 present the sociodemographic characteristics of the adolescents and adults participating in the survey for the Australian and Spanish populations, respectively. The samples were representative of the Australian and Spanish general populations in terms of age, sex and geographical distribution. Higher-education levels of 22% and 17% in Australia and Spain, respectively, were substantially higher than general population estimates (Tables 1, 2). Fewer Australian adults were working full-time than population estimates (35% vs. 58%).

Adults completing from a child perspective took the most time to complete the whole survey and the BSW task, with adolescents completing in the shortest time on average (Table 3). The differences in time taken across years of adolescent age do not appear to be large (Table 3).

3.2 Self-Reported EQ-5D Youth Version (EQ-5D-Y)

The distribution of self-reported EQ-5D-Y and general health responses are presented in Table 4. Overall in both Australian and Spanish samples, adolescents exhibited fewer problems in all EQ-5D-Y dimensions and better general health than adult participants. Both adolescents and adults in Australia and Spain were mostly likely to report some problems in the area of ‘worried, sad or unhappy’. Adults were additionally likely to report problems with pain. Australian adolescents reported the least problems in the area of ‘no problems walking about’. Spanish adolescents and adults and Australian adults reported the least problems in ‘looking after myself’.

3.3 Best–Worst Choice Frequencies

The best and worst pair frequencies are tabulated in ESM Tables 3, 4 and 5 for Spain and 6–8 for Australia and include all 180 possible best–worst pairs. Results show that ‘pain and discomfort’ and ‘sad, worried and unhappy’ are more often rated as best and worst from the pairs presented.

There was a high degree of consistency within dimensions across adolescent and adult responses. For all three samples relating to three valuation perspectives there was a logical ordering, with ‘a lot of problems’ consistently rated more as ‘worst’ than ‘some problems’ and ‘no problems’. The reverse was true for the levels most consistently rated as best. There was slightly more variation across adolescent and adult samples for the worst ratings than the best.

Table 5 reports the sample aggregate best and worst choice counts summary data across samples and countries. For Australian respondents, when each of the health state pairs were presented in the survey the dimension most consistently rated as ‘best’ by adolescents was ‘no problems walking about’ (mobility, rated best 48.2% of times presented). For adults, ‘no pain and discomfort’ was most consistently rated best (47.2%) and for adults answering from a child perspective, ‘no problems with usual activities was most consistently rated best (49.3%). For Spanish respondents, the dimension most consistently rated as ‘best’ for adolescents (50.8%), adults (50.6%) and adults answering from a child perspective (54.8%) was ‘no pain and discomfort’.

The EQ-5D-Y dimension most consistently rated as ‘worst’ by Australian adolescents was being ‘very worried, sad or unhappy’ (rated worst 43.8% of times presented) compared with the dimension rated as ‘worst’ by Australian adults and adults answering from a child perspective of ‘a lot of pain and discomfort’ (49.5% and 56.5%, respectively). For Spanish respondents, the dimension most consistently rated as ‘worst’ for adolescents (43%), adults (44.1%) and adults answering from a child perspective (53%) was ‘a lot of pain and discomfort’.

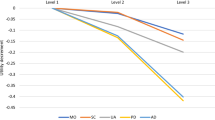

Figure 1a, b plot best/worst choice frequencies and show a clear declining trend between best and worst ratings, or in other words the ‘no health problems’ levels are more often chosen as best and the ‘a lot of problems’ levels are more often chosen as worst. Such a trend is similar between the different perspectives and across countries. There is evidence of similar proportions of levels chosen for best or worst in the three samples (reflecting three valuations perspectives) or two countries, or in other words participants did not seem to struggle to differentiate levels they considered best or worst. The figures also show a clear gap between 0.15–0.3 in Australia and 0.2–0.29 in Spain, indicating that no particular EQ-5D-Y level in any dimension was simultaneously best and worst at the same time. This was reassuring and also demonstrated a similar level of consistency in choices between perspectives and across both countries.

3.4 Dominant Choice Sets

Table 6 presents the proportion of responders who correctly selected the best or worst level for health state scenarios in which there is clearly a best or worst expected choice. This is presented as a measure of validity. The adult Australian and Spanish sample participants were able to select the clearly worst level with a higher level of accuracy relative to adolescents. Adolescents were, however, able to select the expected best level with a similar and in some cases improved level of accuracy compared with the adult samples. There were no clear trends with adolescent age.

3.5 Self-Reported Difficulty

Adolescents reported greater difficulty completing the survey and task than adults in both countries (Table 7). Self-reported difficulty was also greater for children aged 11 years in both countries and approached adult responses by age 16–17 years (Table 7). Adults completing the survey from the perspective of a child also reported more difficulty completing the task in both countries than adults completing from their own perspective (Table 7).

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary of Findings

This study using the same methodology across two countries has shown that adolescents can complete BWS tasks for the EQ-5D-Y instrument. Important country-specific impacts of valuation perspective were identified with the dimensions most rated as best and worst. Australian adults answering from both perspectives (their own and that of a 10-year-old child) appear to place less weight on being very worried, sad or unhappy and more weight instead on having pain or discomfort than Australian adolescents. Spanish adults and adolescents concurred in their greatest weight being placed on pain or discomfort.

4.2 Feasibility and Validity

This is the first published report of adolescent versus adult valuation for the EQ-5D-Y. It directly compared adolescent preferences down to 11 years of age with adult preferences from two perspectives. Sample validation statistics such as completion time, consistency in ordering, rational responses to dominant choice sets and balanced distribution of best–worst frequencies indicate that adolescents were able to engage with the task, complete the task, and provide valid and rational responses. This compares with previous literature on the CHU-9D that also demonstrated the ability of adolescents as young as 11 years to complete CHU-9D valuations [11]. Our research did not identify inconsistencies in the worst choices in adolescents compared with adults, as previously reported by Ratcliffe et al. [11] for the CHU-9D valuations. Adolescents self-reported more difficulty with the task, but when restricting the sample to just those reporting difficulty there was no associated impact on best/worst differentiation or inconsistencies.

4.3 How Young Can Adolescents Make Preference-Based Valuations?

Most of our findings were additionally split by year of child age to enable a thorough investigation of the relationship between average age and task validity. We found that there was an increase in self-reported difficulty for a child aged 11 years compared with older ages; by age 16–17 years adolescents were reporting a similar degree of difficulty to the adult sample. Most validation statistics such as time to complete, consistency in ordering of best and worst frequencies and the distribution of best–worst counts indicate that adolescents 11 years of age are able to validly complete the task. For some analyses, such as best dominant choice sets, adolescents aged 11 years performed better than those at older ages.

4.4 Best–Worst Scaling Methods

BWS methods have been previously applied in paediatric HRQoL preference-based valuations [11]. The choice of BWS for our research was based on its relative cognitive simplicity and a desire to include young adolescents. It is acknowledged that there are difficulties and concerns when using the BWS for health state valuation [25]. The focus of this paper was on the comparison of preferences between samples and ages for which BWS is an appropriate methodology. Future research intending to produce utility values will need to carefully weigh the pragmatic advantages of BWS against the methodological limitations such as the challenges with anchoring and concerns with stability, monoticity and continuity [25]. The BWS method does not automatically provide values that are anchored to the 0–1 (dead–full health) scale as is required for utility measurement. This provides a challenge and means a separate task is required to anchor the BWS responses onto a 0–1 scale as outlined in more detail in Rowen et al. [15, 26].

4.5 Whose Preferences? How Do We Use These Preferences?

This research intended to inform the research question of whose preferences to use for the valuation of adolescent MAUIs. Normative decisions have historically relied on adult preferences presumably because of adults’ role as tax payers and the main economic contributors in society. The role of adolescents being a part of the population sample for obtaining normative preferences is raised with many adolescents now paying tax and contributing to society in a way that may justify their inclusion [19]. If adolescent preferences don’t vary from adult preferences, then the implications of the normative choice are minor; however, if they do vary, the implications could be significant. Likewise, if adolescents and children are unable to provide valid and reliable preferences, the implications for the normative choice are also less important.

We have demonstrated that, for the EQ-5D-Y, using BWS it is feasible and valid to seek preferences from adolescents. Given that their preferences are valid and feasible, the choice about ‘whose preferences?’ then becomes a normative question largely answered by the needs and values of decision makers who wish to use the information. If adolescents are deemed to be social contributors, then there may be a case for inclusion of their preferences in the normative preference set. For use of preferences within economic evaluations, national health schemes may wish to include adolescent values as a part of the population sample, although there may be challenges about how to combine the data and availability of adolescent data to use in anchoring. Choice of anchoring technique is also likely to matter for the resultant utility values generated [27]. It is worth noting that a normative preference set is not the only use for adolescent preferences. In emerging areas of research such as patient-reported outcomes, patient preferences are increasingly being used to guide individual clinical decisions or resource allocation decisions solely within child health services. In these instances, if adolescents or children are the target patients then their preferences will be directly relevant [28].

4.6 Strengths and Limitations

This study is the first to compare adult and adolescent preferences for EQ-5D-Y dimensions. The inclusion of three perspectives (adolescent, adult and adult taking the perspective of a child) and the cross-country comparison are likewise unique. A strength of our study is the utilisation of identical methodology, thereby facilitating a direct comparison and confirming that the difference in preferences observed between these two settings are probably cultural. Our work has also shown the descriptive power of BWS tasks when analysing choice responses without the need for a discrete choice model [24]. Our current analysis assumes that preferences within each sample and perspective in each country are homogeneous and future analyses will explore the role of heterogeneity of preferences on the current results.

Due to resource and time constraints and the desire to attain a geographically representative sample, we chose an online survey method. Online survey methods have been linked with concerns about the understanding and engagement of participants and have led to responses that differ from face-to-face administration [29], although others have shown no impact [7]. However, our results suggest that all samples engaged rationally with the task and that results were sensible and consistent, as shown by the validation statistics presented. Lacking the face-to-face contact with participants means that researchers are not able to directly gauge or clarify lack of understanding of the task.

Our sample was population representative based on age, sex and geography but, as is common for research, we had an over-representation of educated and higher-income participants. This may mean that the values generated are not fully representative of the population. Given the unrepresentativeness of our samples in some key characteristics, if these data are to be used in generating value sets in Spain and Australia, techniques such as probability weighting should be explored.

5 Next Steps and Future Research

This study has provided much-needed new evidence in the area of paediatric preference-based quality-of-life measurement; however, there is a great need for further advancement. As yet, only a US value set exists in the published literature for the EQ-5D-Y [18], meaning serious restrictions on its use within economic evaluation across countries. The practice of instead using the EQ-5D instrument designed for adults still pervades despite it not being age appropriate and differing from a child measure in important ways [20, 30]. There is a need for further research to understand whether children can validly complete DCE-type exercises or DCE with duration. Previously children have been shown to struggle with TTO exercises [31], although other studies have been successfully completed with children [13]. This research exercise included children as young as age 11 years. It is unlikely based on average normal cognitive development and our results for 11 year old’s that valuation much younger will be valid or desirable. Methodological research is needed on how to combine adult and adolescent preferences to form a population normative sample and how to anchor adolescent responses coming from DCE and BWS tasks. More research is required to demonstrate appropriate use and the value of adolescent versus adult preferences for specific decision contexts and scoring algorithms for the EQ-5D-Y are needed [20]. The field eagerly awaits these developments.

6 Conclusions

Our results suggest that inclusion of adolescents in direct valuation of the EQ-5D-Y using online BWS is feasible and valid based on measures such as time to complete, consistency in ordering, rational responses to dominant choice sets and balanced distribution of best–worst frequencies. Adolescents from age 11 to 17 years were able to engage and complete the task. We also found that there are age-related and country-specific differences for Australia and Spain in EQ-5D-Y dimension preferences.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2013.

Commonwealth of Australia. Guidelines for preparing a submission to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Version 5.0. Canberra: Australian Government, Department of Health; 2016.

New Zealand Government. Guidelines for funding applications to PHARMAC. Auckland: Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC), New Zealand Government; 2017.

Chen G, Ratcliffe J. A review of the development and application of generic multi-attribute utility instruments for paediatric populations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(10):1013–28.

Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Saloman J, Tsuchiya A. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017.

Craig BM, Busschbach JJ, Salomon JA. Keep it simple: ranking health states yields values similar to cardinal measurement approaches. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(3):296–305.

Mulhern B, Longworth L, Brazier J, Rowen D, Bansback N, Devlin N, et al. Binary choice health state valuation and mode of administration: head-to-head comparison of online and CAPI. Value Health. 2013;16(1):104–13.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burström K, Cavrini G, et al. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the EQ-5D-Y: results from a multinational study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):887–97.

Thorrington D, Eames K. Measuring health utilities in children and adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135672.

Ratcliffe J, Couzner L, Flynn T, Sawyer M, Stevens K, Brazier J, et al. Valuing Child Health Utility 9D health states with a young adolescent sample: a feasibility study to compare best-worst scaling discrete-choice experiment, standard gamble and time trade-off methods. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2011;9(1):15–27.

Ratcliffe J, Huynh E, Stevens K, Brazier J, Sawyer M, Flynn T. Nothing about us without us? A comparison of adolescent and adult health-state values for the Child Health Utility-9D using profile case best–worst scaling. Health Econ. 2016;25(4):486–96.

Ratcliffe J, Stevens K, Flynn T, Brazier J, Sawyer MG. Whose values in health? An empirical comparison of the application of adolescent and adult values for the CHU-9D and AQOL-6D in the Australian adolescent general population. Value Health. 2012;15(5):730–6.

Moodie M, Richardson J, Rankin B, Iezzi A, Sinha K. Predicting time trade-off health state valuations of adolescents in four Pacific countries using the Assessment of Quality-of-Life (AQoL-6D) instrument. Value Health. 2010;13(8):1014–27.

Apajasalo M, Sintonen H, Holmberg C, Sinkkonen J, Aalberg V, Pihko H, et al. Quality of life in early adolescence: a sixteen-dimensional health-related measure (16D). Qual Life Res. 1996;5(2):205–11.

Rowen D, Rivero-Arias O, Devlin N, Ratcliffe J. Review of valuation methods of preference-based measures of health for economic evaluation in child and adolescent populations: where are we now and where are we going? Pharmacoeconomics. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00873-7.

Crump RT, Beverung LM, Lau R, Sieracki R, Nicholson M. Reliability, validity, and feasibility of direct elicitation of children’s preferences for health states: a systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2017;37(3):314–26.

Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care. 1997;35:1095–108.

Craig BM, Greiner W, Brown D, Reeve B. Valuation of child-related quality of life in the United States. Health Econ. 2016;25:768–77.

Kind P, Klose K, Gusi N, Olivares PR, Greiner W. Can adult weights be used to value child health states? Testing the influence of perspective in valuing EQ-5D-Y. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(10):2519–39.

Kreimeier S, Greiner W. EQ-5D-Y as a health-related quality of life instrument for children and adolescents: the instrument’s characteristics, development, current use, and challenges of developing its value set. Value Health. 2019;22(1):31–7.

McCabe C, Stevens K, Roberts J, Brazier J. Health state values for the HUI 2 descriptive system: results from a UK survey. Health Econ. 2005;14(3):231–44.

Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burström K, Cavrini G, Devlin N, et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):875–86.

Currie C, Molcho M, Boyce W, Holstein B, Torsheim T, Richter M. Researching health inequalities in adolescents: the development of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) family affluence scale. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1429–36.

Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Marley AAJ. Best-worst scaling: theory, methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015.

Krucien N, Watson V, Ryan M. Is best-worst scaling suitable for health state valuation? A comparison with discrete choice experiments. Health Econ. 2017;26(12):e1–16.

Rowen D, Brazier J, Van Hout B. A comparison of methods for converting DCE values onto the full health-dead QALY scale. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(3):328–40.

Norman R, Mulhern B, Viney R. The impact of different DCE-based approaches when anchoring utility scores. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(8):805–14.

Fraenkel L. Incorporating patients’ preferences into medical decision making. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(1 Suppl):80s–93s.

Rowen D, Brazier J, Keetharuth A, Tsuchiya A, Mukuria C. Comparison of modes of administration and alternative formats for eliciting societal preferences for burden of illness. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2016;14(1):89–104.

Matza LS, Patrick DL, Riley AW, Alexander JJ, Rajmil L, Pleil AM, et al. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: report of the ISPOR PRO good research practices for the assessment of children and adolescents task force. Value Health. 2013;16(4):461–79.

Ratcliffe J, Chen G, Stevens K, Bradley S, Couzner L, Brazier J, et al. Valuing Child Health Utility 9D health states with young adults: insights from a time trade off study. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2015;13(5):485–92.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the adolescent and adult participants in Australia and Spain who completed the questionnaire; without them, this work would not have been possible. Special thanks are given to Cristina Valcarcel-Nazco for her assistance setting up the study and monitoring data collection in Spain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OR-A secured funding for the study, designed the study and is the study guarantor. KD and MC wrote the first draft of the manuscript with contributions from all authors. OR-A, BG-L and IG conducted the statistical analysis of the Spanish samples and MC, KD and OR-A conducted the statistical analysis of the Australian samples. All authors approved the final version submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and FEDER (European Regional Development Fund) (PI14/00619). The study sponsors had no role in the analysis and interpretation of data; writing this document; or in the decision to submit this work to publication.

Conflict of interest

Oliver Rivero-Arias and Richard Norman are members of the EuroQol Group (the copyright holders of the EQ-5D-Y). Kim Dalziel, Max Catchpool, Borja García-Lorenzo and Inigo Gorostiza have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study received ethics approval from the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (#1750456) and the Ethics Committee at the University Hospital Nuestra Señora de Candelaria in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain (#PI-26/14).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dalziel, K., Catchpool, M., García-Lorenzo, B. et al. Feasibility, Validity and Differences in Adolescent and Adult EQ-5D-Y Health State Valuation in Australia and Spain: An Application of Best–Worst Scaling. PharmacoEconomics 38, 499–513 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00884-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00884-9