Abstract

Background

Linaclotide is a well-tolerated and effective agent for adults with functional constipation (FC) or irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C). However, data in children are lacking. The aim of this study is to examine the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in children.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of children < 18 years old who started linaclotide at our institution (Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, Ohio). We excluded children already using linaclotide or whom had an organic cause of constipation or abdominal pain. We recorded information on patient characteristics, medical and surgical history, symptoms, clinical response, course of treatment, and adverse events at baseline, first follow-up, and after 1 year of linaclotide use. A positive clinical response was based on the physician’s global assessment of symptoms at the time of the visit as documented.

Results

We included 93 children treated with linaclotide for FC (n = 60) or IBS-C (n = 33); 60% were female; median age was 14.7 years (IQR 13.2–16.6). Forty-five percent of patients with FC and 42% with IBS-C had a positive clinical response at first follow-up a median of 2.5 and 2.4 months after starting linaclotide, respectively. Approximately a third of patients experienced adverse events and eventually 27% stopped using linaclotide due to adverse events. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and bloating.

Conclusion

Nearly half of children with FC or IBS-C benefited from linaclotide, but adverse events were relatively common. Further prospective, controlled studies are needed to confirm these findings and to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from linaclotide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Approximately 50% of children with functional constipation (FC) or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) remain symptomatic with conventional treatment. |

Linaclotide is a guanylate cyclase-C receptor agonist and may be beneficial for some children with FC (45%) and IBS with constipation (42%). |

Adverse events, especially diarrhea, are common and led to discontinuation of linaclotide in nearly a third of children. |

1 Introduction

Functional gastrointestinal disorders are common in pediatrics, affecting nearly a third of children in population-based studies [1, 2]. The two most common pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders are functional constipation (FC), with a global pooled prevalence of 9.5%, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), with a pooled prevalence of 12% [3, 4]. Both disorders are diagnosed with the symptom-based Rome IV criteria [5]. Conventional treatment of FC includes education, behavioral intervention with toilet training, and oral laxatives [6]. Treatment of IBS consists of education, dietary changes, behavioral therapy, hypnotherapy, and pharmacologic treatment, although in children the evidence for benefit of pharmacological treatment is very limited [7].

Long-term follow-up studies have shown that a significant proportion of children with FC and IBS continue to struggle with symptoms despite conventional treatment [8,9,10]. In addition, these conditions have a detrimental impact on quality of life for both the children and their family [11, 12]. Therefore, there is a need to identify new therapeutic options [13]. In the past decade, a number of novel pharmacologic treatments have emerged for adults with FC and IBS with constipation (IBS-C) [13]. One of these is linaclotide, a guanylate cyclase-C receptor agonist that activates intracellular conversion of guanosine 5-triphosphate to cyclic guanosine monophosphate, resulting in intestinal fluid secretion, accelerated gut transit, and a decrease in visceral hypersensitivity in stress-induced and inflammation-induced visceral pain [14]. The drug uses a pathway that has not yet been used before in the treatment of children with FC or IBS-C and may be helpful for children who do not respond to conventional therapy. Linaclotide has been shown to be safe and effective for adults with FC and IBS-C and is included in current practice guidelines for adults with these conditions [15,16,17,18]. To date, the use of linaclotide in children with FC or IBS-C has not been published in peer-reviewed literature. The objective of our study is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of linaclotide in children with FC or IBS-C.

2 Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of all children who were prescribed linaclotide for FC or IBS-C at our institution (Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, Ohio) between September 2013 and May 2019. We included patients 0–18 years of age who were treated with linaclotide during this period and had follow-up data (i.e., telephone encounter or office visit) available. We excluded patients who were already on linaclotide at the time of their initial presentation at our institution and those with other gastrointestinal disorders that could contribute to constipation or abdominal pain. Data on patient characteristics, medical and surgical history, symptoms, clinical response, linaclotide dosing, course of treatment, and adverse events were collected and stored in a REDCap electronic data capture database [19]. Follow-up data were divided into initial and long-term follow-up (> 1 year). If the initial follow-up was after 1 year, data was included in both follow-up time points. If children had multiple long-term follow-up time points, we used the data closest to 1 year. Because of the retrospective nature of our study and reliance on information recorded in the patient charts, we recorded most clinical outcomes as binary variables. A positive clinical response was determined based on the physician’s global assessment of symptoms at the time of the visit as documented in the patients’ medical records. This study was reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board of Nationwide Children’s Hospital (Columbus, Ohio, USA).

Data distribution was evaluated by both visual inspection of means, standard deviations, medians, histograms, and Q–Q plots, as well as by statistical testing with the use of the Shapiro–Wilk test. Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics (median, interquartile range, number, percentage). We compared baseline and follow-up data using McNemar’s test or Wilcoxon signed rank test as appropriate. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows, version 24 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3 Results

We identified 269 patients who were prescribed linaclotide at our institution (Fig. 1). The majority of patients were excluded because no follow-up data was available, or patients did not start using the medication. Primary reasons for not starting the medication were lack of insurance coverage and high cost (the current list price in the US is $445 per month depending on dosage and pharmacy costs [20]). We included 93 patients in the analysis (60% female, median age 14.7 years, range 8–17 years). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. All included patients had a diagnosis of FC (n = 60; 64.5%) or IBS-C (n = 33; 35.5%). Nineteen patients (20%) had previously undergone a surgical intervention. The most common intervention was an appendicostomy or cecostomy procedure (10 patients, 11%). Eight patients (9%) had tried lubiprostone before starting linaclotide and 25 patients (27%) were using lubiprostone before starting linaclotide. At time of starting linaclotide, 50 patients (FC n = 25; IBS-C n = 25) had additional treatment changes simultaneously with the start of linaclotide. In 40 patients, starting linaclotide was accompanied with a discontinuation of one or more drugs (lubiprostone [n = 24], polyethylene glycol [n = 6], senna [n = 3], wean antegrade flushes [n = 2], docusate tablet [n = 2], lactulose [n = 2], bisacodyl [n = 1], milk of magnesia [n = 1]). In five patients, the additional change entailed the addition of another intervention (start bisacodyl [n = 3], start glycerin [n = 1], start FODMAD diet [n = 1]). In the remaining five patients, the start of linaclotide was accompanied by a combination of an addition/discontinuation of other interventions. Moreover, four patients (4%) had a clean-out at start of linaclotide. The majority of patients (n = 78; 84%) started with a dose of 145 µg daily. The median age of children starting with 72 µg was similar to that of children starting with 145 µg (median age 14.5 years [IQR 12.6–15.8] and median age 14.8 years (IQR 13.3–16.6), respectively).

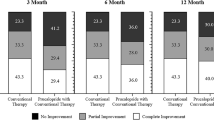

3.1 Functional Constipation

As shown in Table 2, 50 (83%) of the 60 patients with FC used linaclotide until their first follow-up 2.5 months (median) after starting linaclotide. Among those patients, 27/50 (54%) reported a positive clinical response, meaning that 45% of the initial 60 patients reported to have benefited from using linaclotide. Compared with baseline, fewer patients complained of symptoms of constipation (40/48 [83%] vs 17/32 [64%]; p = 0.039) and patients reported more frequent bowel movements (from a median of 4 bowel movements per week [IQR 2–7] to 7 [IQR 7–7]; p = 0.027).

After the first follow-up visit, 44/60 (73%) patients continued to use linaclotide. Fifteen of these 44 patients continued to use linaclotide and returned to follow-up after a year of treatment. At a median of 17 months after starting linaclotide, 14/15 (93%) remained on linaclotide and 13/14 (93%) continued to report a positive clinical response. Ten of 44 patients stopped using linaclotide between their first follow-up and long-term follow-up. Nineteen of 44 patients were still using linaclotide at their latest follow-up but did not have follow-up data after 1 year. None of the patients who had a positive clinical response stopped the medication during the follow-up interval. There were no statistically significant differences between reported abdominal pain, fecal incontinence, or painful/hard bowel movements at baseline compared with first and long-term follow-up.

3.2 IBS-C

As shown in Table 3, 24 (73%) of the 33 patients with IBS-C used linaclotide until their first follow-up 2.4 months (median) after starting linaclotide. Of those patients, 14/24 (58%) reported a positive clinical response, meaning that 42% of the initial 33 patients reported to have benefited from using linaclotide.

After the first follow-up visit, 23/33 (70%) patients continued to use linaclotide. Eight of these patients continued to use linaclotide and returned to follow-up after a year of treatment. At a median of 17 months after starting linaclotide, 7/8 (88%) remained on linaclotide and 6/7 (73%) continued to report a positive clinical response. Three of 23 patients stopped using linaclotide between their first follow-up and long-term follow-up. Fifteen of 23 patients were still using linaclotide at their latest follow-up but did not have follow-up data after 1 year. None of the patients who had a positive clinical response stopped the medication during the follow-up interval. There were no statistically significant differences between reported constipation, bowel movement frequency, abdominal pain, or fecal incontinence at baseline compared with first and long-term follow-up.

3.3 Patients with a Surgical History

Among the 19 patients with a surgical history, 17 (89%) used linaclotide until their first follow-up. Of those patients, 9/16 (56%) reported a positive clinical response. Two (22%) of the nine patients who were using antegrade continence enemas at baseline were able to successfully completely wean off the antegrade flushes while using linaclotide during our complete follow-up.

3.4 Adverse Events

At the time of the first follow-up appointment, 33/93 (35%) of patients reported adverse events and 12/93 (13%) had discontinued linaclotide before their first follow-up because of adverse events. Adverse events included diarrhea (n = 17), (increase in) abdominal pain (n = 11), nausea (n = 7), flatulence (n = 4), fecal incontinence (n = 4), bloating (n = 3), dizziness (n = 2), headaches (n = 2), weight gain (n = 1), diaphoresis (n = 1), and mucus in their stools (n = 1). The most commonly reported adverse events are broken down to diagnosis and prescribed linaclotide dose in Table 4. None of the adverse events required hospitalization. After the first follow-up visit, two patients who had stopped linaclotide restarted the medication, but another nine patients decided to stop using linaclotide because of adverse events, resulting in 19/93 patients (20%) who had discontinued linaclotide because of adverse events at first follow-up. After their initial follow-up, another six patients stopped using linaclotide because of adverse events, resulting in a total of 25/93 (27%). At long-term follow-up, two patients reported adverse events at their follow-up including diarrhea and bloating.

4 Discussion

This retrospective study suggests that linaclotide may be of value for the treatment of some children with FC or IBS-C. Adverse events were reported in 35% of patients at their initial follow-up and 20% stopped using the medication because of these adverse events.

For patients with FC, we found that around 45% reported benefit at first folllw-up. In accordance with what is reported in adults with FC, we found that linaclotide significantly improved bowel movement frequency [15]. Since this study was not controlled, nor blinded, part of this benefit may be due to placebo effect, which can range between 17–32% in this population [21,22,23]. However, we believe these results are still promising since our population consisted of children with particularly severe symptoms, including patients with antegrade continence enema use (13%), a history of sacral nerve stimulation (7%), and partial colonic resection (5%).

As for patients with IBS-C, we found that around 40% of patients reported benefit at first follow-up but we found no significant differences in reported symptoms. However, our sample size for patients with IBS-C was relatively small and our outcomes were not as specific as those used in other trials [24, 25]. An abstract was recently published reporting the preliminary results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on linaclotide treatment that included 173 children diagnosed with IBS-C aged 6–17 years [26]. The investigators did not find significant improvement in spontaneous bowel movement frequency with linaclotide when compared with placebo but reported a trend towards efficacy at higher doses. The doses used in this study were dependent on age and weight and ranged between 18 µg and 290 µg, where 145 µg was considered a high dose. In contrast, in our study the most common dose used was 145 µg (78 patients; 84%). Given our study design, it is possible that the benefit we observed was in part secondary to placebo effect, and a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found a similar placebo effect of around 40% for children with abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders [27]. It may also be possible that the improvement we observed resulted from the higher doses used in our study. Adult studies investigating the effect of linaclotide on patients with IBS-C showed that, compared with placebo, linaclotide improved both abdominal pain and bowel symptoms [16, 28,29,30].

Adverse events were common in our study. At initial follow-up, 35% of patients reported adverse events and 20% stopped using linaclotide because of them. This number is high compared with the previously mentioned abstract of the pediatric trial [26]. The frequency of adverse events in our study was similar to that described in adult studies. In adults, diarrhea is the most common adverse event with a prevalence of 20%; we found that diarrhea was reported in 18% of all children (16). However, over the course of our study, 27% of patients eventually stopped linaclotide because of adverse events, which is higher than the 9% discontinuation rate in adults treated with linaclotide [31]. This may be secondary to the relatively higher doses used in our patient population or be caused by other medications and/or interactions.

The primary strength of this study is that it is the first to report on the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in a fairly large cohort of pediatric patients with FC and IBS-C in clinical practice. Furthermore, we looked into other medication changes and described in detail the characteristics of our study population. However, there are several limitations of this study inherent to its design as a retrospective review. Our data were based on what was documented in the medical chart. As noted previously, over half of our patients had additional treatment changes at the time of starting linaclotide, making it difficult to attribute the subsequent effects and adverse events solely to linaclotide. The majority of patients who were prescribed linaclotide did not start treatment because of insurance denial and/or too high costs. In addition, the majority of children with FC were older than the average age of children presenting with FC and a substantial subset had undergone a surgical intervention for their constipation. Therefore, our sample likely represents a particularly severe patient population with symptoms refractory to conventional treatment, limiting the generalizability of our findings to all children with FC and IBS-C. Lastly, the improvement noted at long-term follow-up should be interpreted with caution as improvement may be secondary to the natural history of the disorders, as well as other interventions initiated during the follow-up period.

5 Conclusion

In this review of our experience with children with FC or IBS-C treated with linaclotide, over 40% of patients reported benefit and we found significant improvement in constipation symptoms in children with FC. However, adverse events were common and nearly a third of patients stopped using linaclotide because of them. Our findings suggest that linaclotide may be of value in the treatment of some pediatric patients with FC or IBS-C if symptoms persist despite conventional treatment. However, more research is needed to better understand the efficacy and safety of various doses of linaclotide in children and adolescents, and to identify which children may be more likely to respond well to linaclotide treatment.

References

Robin SG, Keller C, Zwiener R, Hyman PE, Nurko S, Saps M, et al. Prevalence of pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders utilizing the Rome IV criteria. J Pediatr. 2018;195:134–9.

Saps M, Velasco-Benitez CA, Langshaw AH, Ramírez-Hernández CR. Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents: comparison between Rome III and Rome IV criteria. J Pediatr. 2018;199:212–6.

Korterink JJ, Diederen K, Benninga MA, Tabbers MM. Epidemiology of pediatric functional abdominal pain disorders: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126982-e.

Koppen IJN, Vriesman MH, Saps M, Rajindrajith S, Shi X, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, et al. Prevalence of functional defecation disorders in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;198:121–30.

Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1456–1468.

Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY, Faure C, Langendam MW, Nurko S, et al. Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58(2):258–74.

Abbott RA, Martin AE, Newlove-Delgado TV, Bethel A, Whear RS, Thompson Coon J, et al. Recurrent abdominal pain in children: summary evidence from 3 systematic reviews of treatment effectiveness. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67(1):23–33.

van Ginkel R, Reitsma JB, Buller HA, van Wijk MP, Taminiau JA, Benninga MA. Childhood constipation: longitudinal follow-up beyond puberty. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(2):357–63.

Campo JV, Di Lorenzo C, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Colborn DK, Gartner JC Jr, et al. Adult outcomes of pediatric recurrent abdominal pain: do they just grow out of it? Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):E1.

Giannetti E, Maglione M, Sciorio E, Coppola V, Miele E, Staiano A. Do children just grow out of irritable bowel syndrome? J Pediatr. 2017;183:122–6.

Varni JW, Lane MM, Burwinkle TM, Fontaine EN, Youssef NN, Schwimmer JB, et al. Health-related quality of life in pediatric patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a comparative analysis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(6):451–8.

Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Weerasooriya L, Hathagoda W, Benninga MA. Quality of life and somatic symptoms in children with constipation: a school-based study. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1069-72. e1.

Devanarayana NM, Rajindrajith S. Irritable bowel syndrome in children: current knowledge, challenges and opportunities. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(21):2211.

Bassotti G, Usai-Satta P, Bellini M. Linaclotide for the treatment of chronic constipation. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19(11):1261–6.

Lembo AJ, Schneier HA, Shiff SJ, Kurtz CB, MacDougall JE, Jia XD, et al. Two randomized trials of linaclotide for chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):527–36.

Atluri D, Chandar A, Bharucha AE, Falck-Ytter Y. Effect of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26(4):499–509.

Hookway C, Buckner S, Crosland P, Longson D. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:

Serra J, Pohl D, Azpiroz F, Chiarioni G, Ducrotté P, Gourcerol G, et al. European society of neurogastroenterology and motility guidelines on functional constipation in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(2):e13762.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

pricing A. What will I pay for LINZESS®? 2020. https://www.allerganpricing.com/linzess.

Mugie SM, Korczowski B, Bodi P, Green A, Kerstens R, Ausma J, et al. Prucalopride is no more effective than placebo for children with functional constipation. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(6):1285–95.e1.

Baştürk A, Artan R, Atalay A, Yılmaz A. Investigation of the efficacy of synbiotics in the treatment of functional constipation in children: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28(5):388–93.

Bekkali NLH, Hoekman DR, Liem O, Bongers MEJ, van Wijk MP, Zegers B, et al. Polyethylene glycol 3350 with electrolytes versus polyethylene glycol 4000 for constipation: a randomized, controlled trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(1):10–5.

Rutten J, Vlieger AM, Frankenhuis C, George EK, Groeneweg M, Norbruis OF, et al. Home-based hypnotherapy self-exercises vs individual hypnotherapy with a therapist for treatment of pediatric irritable bowel syndrome, functional abdominal pain, or functional abdominal pain syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(5):470–7.

Vlieger AM, Menko–Frankenhuis C, Wolfkamp SCS, Tromp E, Benninga MA. Hypnotherapy for children with functional abdominal pain or irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(5):1430–6.

Di Lorenzo C, Nurko S, Hyams JS, Weissman T, Borgstein N, Mallick M, et al. Linaclotide safety and efficacy in children aged 6 to 17 years with functional constipation: 1151. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:S645–6.

Hoekman DR, Zeevenhooven J, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, Douwes Dekker I, Benninga MA, Tabbers MM, et al. The placebo response in pediatric abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2017;182:155–63.

Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ, Shiff SJ, Kurtz CB, Currie MG, et al. Linaclotide for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1702–12.

Pohl D, Fried M, Lawrance D, Beck E, Hammer HF. Multicentre, non-interventional study of the efficacy and tolerability of linaclotide in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation in primary, secondary and tertiary centres: the Alpine study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e025627.

Taylor DC, Abel JL, Doshi JA, Martin C, Hunter AG, Essoi B, et al. The impact of stool consistency on bowel movement satisfaction in patients with IBS-C or CIC treated with linaclotide or other medications: real-world evidence from the CONTOR study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53(10):737.

Medication Guide Linaclotide. 2012 5-28-2020]; https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/202811s013lbl.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baaleman, D.F., Gupta, S., Benninga, M.A. et al. The Use of Linaclotide in Children with Functional Constipation or Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Retrospective Chart Review. Pediatr Drugs 23, 307–314 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-021-00444-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-021-00444-4