Abstract

Polypharmacy, defined as the concomitant use of two or more psychotropic drugs, has become increasingly common in the paediatric and adolescent population over the past two decades. Combining psychotropic drugs leads to possible increases in benefits, but also in risks, particularly given the potential for psychotropic drug interactions. Despite the increasing use of concomitant therapy in children and adolescents, there is very little evidence from controlled clinical trials to provide guidance for prescribers. Even while acknowledging the small evidence base, clinical practice guidelines from eminent medical organizations are either relatively silent on or tend to support the use of concomitant treatments more enthusiastically than the evidence would warrant, so that practice and guidance are running ahead of the science. Our narrative review shows that the published evidence for efficacy and safety of concomitant psychotropic drugs in children and adolescents is scanty. A comprehensive search located 37 studies published over the last decade, of which 18 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). These focused mainly on stimulants, central sympatholytics (such as clonidine), antipsychotics and ‘mood stabilizers’. While several small, often methodologically weak, RCTs demonstrated statistically significant advantages for dual pharmacotherapy over monotherapy, only adding central sympatholytics to stimulants for treating attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms was supported by substantial studies with an effect size large enough to suggest clinical importance. Non-randomized studies tended to have results that supported concomitant treatment, but all have design-related problems that decrease the reliability of the results. Two studies that specifically examined tolerability of combination pharmacotherapy compared with monotherapy showed significant increases in adverse effects, both subjective and objective, and other studies confirmed a statistically significant increase in adverse effects, including sedation and self-harm. Given the extent of combination therapy occurring, particularly in conditions such as ADHD, and the ambiguous evidence for benefit with clear evidence of harm, we propose that further research should be carried out as a matter of urgency. Until such a time, the attitude to combination pharmacotherapy should be conservative, and combining psychotropic medications should be considered as an ‘n of 1’ trial to be closely monitored.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Salazar JA, Poon I, Nair M. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly: expect the unexpected, think the unthinkable. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6(6):695–704.

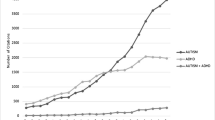

Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996–2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1001–10.

Goodwin G, Fleischhacker W, Arango C, et al. Advantages and disadvantages of combination treatment with antipsychotics. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19(7):520–32.

Joshi G, Gerogiopoulos AM. Combination pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. Rosenberg DR, Gershon S (eds) Pharmacotherapy of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders, chap. 17. 3rd ed. New York: Wiley; 2012.

Pincus HA, Tew JD, First MB. Psychiatric comorbidity: is more less? World Psychiatry. 2004;3(1):18–23.

Beddoe R. Dying for a cure. New York: Random House; 2007.

Rashed AN, Wong ICK, Cranswick N, et al. Risk factors associated with adverse drug reactions in hospitalised children: international multicentre study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011. doi:10.1007/s00228-011-1183-4.

Kaminer Y, Goldberg P, Connor DF. Psychotropic medications and substances of abuse interactions in youth. Subst Abuse. 2010;31:53–7.

Muscatello MR, Spina E, Bandelow B, Baldwin DS. Clinical relevant drug interactions in anxiety disorders. Human Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2012. doi:10.1002/hup.2217. Accessed 29 Mar 2012.

Schellander R, Donnerer J. Antidepressants: clinically relevant drug interactions to be considered. Pharmacology. 2010;86:203–15.

Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Therap. 2008;30(7):1206–27.

Sun-Edelstein C, Tepper SJ, Shapiro RE. Drug-induced serotonin syndrome: a review. Expert Opin Drug Safety. 2008;7:587–96.

Pisani F, Oteri G, Costa C, et al. Effects of psychotropic drugs on seizure threshold. Drug Safety. 2002;25:91–110.

Chen H, Patel A, Sherer J, et al. The definition and prevalence of pediatric psychotropic polypharmacy. Pyschiatric Serv. 2011;62:1450–5.

McIntyre RS, Jerrell JM. Polypharmacy in children and adolescents treated for major depressive disorder: a claims database study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:240–6.

Constantine RJ, Boaz T, Tandon R. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in the treatment of children and adolescents in the fee-for-service component of a large state medicaid program. Clin Therap. 2010;32(5):949–59.

Dean AJ, McDermott BM, Marshall RT. Psychotropic medication utilization in a child and adolescent mental health service. J Child Adolescent Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(3):273–85.

Griffith AK, Huscroft-D’Angelo J, Epstein MH, et al. Psychotropic medication use for youth in residential treatment: a comparison between youth with monopharmacy versus polypharmacy. J Child Fam Stud. 2010;19:795–802.

Russell PSS, George C, Mammen P. Predictive factors for polypharmacy among child and adolescent psychiatry inpatients. Clin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health. 2006;2:25.

Jureidini J, Tonkin A. Overuse of antidepressant drugs for the treatment of depression. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:623–32.

Fontanella CA, Bridge JA, Campo JV. Psychotropic medication changes, polypharmacy and the risk of early readmission in suicidal adolescent inpatients. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1939–47.

Zoega H, Baldursson G, Hrafnkelsson B, et al. Psychotropic drug use among Icelandic children: a nationwide population-based study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19:757–64.

Zito JM, Safer DJ, Jon-van den Berg LTW, et al. A three-country comparison of psychotropic medication prevalence in youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Mental Health. 2008;2:26.

Gerhard T, Chavez B, Olfson M, et al. National patterns of the outpatient pharmacological management of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:307–10.

Zito JM, Safer DJ, Sai D, et al. Psychotropic medication patterns among youth in foster care. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):e157–63.

Duffy FF, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. Concomitant pharmacotherapy among youths treated in routine psychiatric practice. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:12–25.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. CG72 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): full guideline. UK: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2009. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12061/42060/42060.pdf.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. CG28 Depression in Children and Young People. Identification and management in primary, community and secondary care. UK: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2005.

Martin A, Scahill L, Kratochvil C. Pediatric psychopharmacology principles and practice. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University of Press; 2011.

Kutcher S, Chehil S. Physical treatments, Rutter’s child and adolescent psychiatry. 5th ed. New York: Blackwell Publishing Limited; 2008.

Rosenberg D, Gershon S (eds) Pharmacotherapy of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. 3rd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2012.

George JN, Vesely SK, Woolf SH. Conflicts of interest and clinical recommendations: comparison of two concurrent clinical practice guidelines for primary immune thrombocytopenia developed by different methods. Am J Med Qual. 2013;20:1–8.

AACAP. Practice parameter on the use of psychotropic medication in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:9.

Findling RL, McNamara NK, Gracious BL, et al. Combination lithium and divalproex sodium in pediatric bipolarity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(8):895–901.

Steering committee on quality improvement and subcommittee on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1007–22.

Safer DJ, Zito JM, dosReis S. Concomitant psychotropic medication for youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:438–49.

Gittelman-Klein R, Klein DF, Katz S, Saraf K, et al. Comparative effects of methylphenidate and thioridazine in hyperkinetic children, I: clinical results. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1217–31.

Connor DF, Barkley RA, Davis HT. A pilot study of methylphenidate, clonidine, or the combination in ADHD comorbid with aggressive oppositional defiant or conduct disorder. Clin Pediatr. 2000;39:15–25.

Carlson GA, Rapport MD, Kelly KL, et al. Methylphenidate and desipramine in hospitalized children with comorbid behavior and mood disorders: separate and combined effects on behavior and mood. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1995;5:191–204.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:e1–37.

Palumbo DR, Sallee FR, Pelham WE, et al. Clonidine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Efficacy and tolerability outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(2):180–8.

Kurlan R, Tourette’s Syndrome Study Group. Treatment of ADHD in children with tics. Neurology. 2002;58:527–36.

Wilens TE, Bukstein O, Brams M, et al. A controlled trial of extended-release guanfacine and psychostimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):74–85.

Kollins SH, Jain R, Brams M, et al. Clonidine extended-release tablets as add-on therapy to psychostimulants in children and adolescents with ADHD. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):e1406–13.

Kratochvil CJ, Newcorn JH, Arnold LE, et al. Atomoxetine alone or combined with fluoxetine for treating ADHD with comorbid depressive or anxiety symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(9):915–24.

Abikoff H, McGough J, Vitiello B, et al. Sequential pharmacotherapy for children with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity and anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:5.

Hazell P, Jairam R. Acute treatment of mania in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25:264–70.

Cannon M, Pelham WH, Sallee R, CAT Study Team, et al. Effects of clonidine and methylphenidate on family quality of life in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19:511–7.

Hazell PL, Stuart JE. A randomized controlled trial of clonidine added to psychostimulant medication for hyperactive and aggressive children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(8):886–94.

Perera H, Jeewandara KC, Seneviratne S, et al. ADHD refractory to methylphenidate treatment: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study combined Ω3 and Ω6 supplementation in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Neurol. 2012;27:747.

Abbasi SH, Heidari S, Mohammadi MR, Tabrizi M, et al. Acetyl-l-carnitine as an adjunctive therapy in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a placebo-controlled trial. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2011;42(3):367–75.

Blader JC, Schooler NR, Jensen PS, et al. Adjunctive divalproex versus placebo for children with ADHD and aggression refractory to stimulant monotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(12):1392–401.

Armenteros JL, Lewis JE, Davalos M. Risperidone augmentation for treatment-resistant aggression in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a placebo-controlled pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(5):558–65.

Zeni CP, Tramontina S, Ketzer CR, et al. Methylphenidate combined with aripiprazole in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized crossover trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(5):553–61.

Scheffer RE, Kowatch RA, Carmody TC, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of mixed amphetamine salts for symptoms of comorbid ADHD in pediatric bipolar disorder after mood stabilisation with divalproex sodium. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:58–64.

Akhondzadeh S, Mohammadi MR, Khademi M. Zinc sulfate as an adjunct to methylphenidate for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children: a double blind and randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:9.

Arnold LE, Disilvestro RA, Bozzolo D, et al. Zinc for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: placebo-controlled double-blind pilot trial alone and combined with amphetamine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(1):1–19.

Farmer CA, Arnold LE, Bukstein OG, Findling RL, et al. The treatment of severe child aggression (TOSCA) study: design challenges. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;5(1):36.

DelBello MP, Schwiers ML, Rosenberg HL, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as adjunctive treatment for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(10):1216–23.

Akhondzadeh S, Fallah J, Mohammadi MR, et al. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of pentoxifylline added to risperidone: effects on aberrant behavior in children with autism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(1):32–6.

Rezaei V, Mohammadi MR, Ghanizadeh A, Sahraian A, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone plus topiramate in children with autistic disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(7):1269–72.

Sandler AD, Glesne CE, Bodfish JW. Conditioned placebo dose reduction: a new treatment in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(5):369–75.

Spencer TJ, Greenbaum M, Ginsberg LD, Murphy WR. Safety and effectiveness of coadministration of guanfacine extended release and psychostimulants in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(5):501–10.

Sallee FR, Lyne A, Wigal T, McGough JJ. Long-term safety and efficacy of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(3):215–26.

Wilens TE, Hammerness P, Utziner L, et al. An open study of adjunct OROS-methylphenidate in children and adolescents who are atomoxetine partial responders: I. Effectiveness. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(5):485–92.

Snyder R, Turgay A, Aman M, Risperidone Conduct Study Group, et al. Effects of risperidone on conduct and disruptive behavior disorders in children with subaverage IQs. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2002;41(9):1026–36.

Aman MG, DeSmedt G, Derivan A, The Risperidone Disruptive Behavior Study Group, et al. Risperidone treatment of children with disruptive behavior disorders and subaverage IQ: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1337–46.

Aman MG, Binder C, Turgay A. Risperidone effects in the presence/absence of psychostimulant medicine in children with ADHD, other disruptive behavior disorders, and subaverage IQ. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;14(2):243–54.

Kronenberger WG, Giauque AL, Lafata DE, et al. Quetiapine addition in methylphenidate treatment-resistant adolescents with comorbid ADHD, conduct/oppositional-defiant disorder, and aggression: a prospective, open-label study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(3):334–47.

Chang K, Nayar D, Howe M, et al. Atomoxetine as an adjunct therapy in the treatment of co-morbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents with bipolar I or II disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(5):547–51.

Findling RL, McNamara NK, Stansbrey R, et al. Combination lithium and divalproex sodium in pediatric bipolar symptom restabilisation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(2):142–8.

Kafantaris V, Coletti DJ, Dicker R, et al. Adjunctive antipsychotic treatment of adolescents with bipolar psychosis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatryr. 2001;40(12):1448–56.

Kafantaris V, Dicker R, Coletti DJ, et al. Adjunctive antipsychotic treatment is necessary for adolescents with psychotic mania. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001;11(4):409–13.

Kowatch RA, Sethuraman G, Hume JH, Kromelis M, et al. Combination pharmacotherapy in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(11):978–84.

Pavuluri MN, Henry DB, Carbray JA, et al. Open-label prospective trial of risperidone in combination with lithium or divalproex sodium in pediatric mania. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(Suppl 1):S103–11.

Chang K, Saxena K, Howe M. An open-label study of lamotrigine adjunct or monotherapy for the treatment of adolescents with bipolar depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(3):298–304.

Chez MG, Burton Q, Dowling T, et al. Memantine as adjunctive therapy in children diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorders: an observation of initial clinical response and maintenance tolerability. J Child Neurol. 2007;22(5):574–9.

Shamseddeen W, Clarke G, Keller MB, et al. Adjunctive sleep medications and depression outcome in the treatment of serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitor resistant depression in adolescents study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):29–36.

Kondo DG, Sung YH, Hellem TL, et al. Open-label adjunctive creatine for female adolescents with SSRI-resistant major depressive disorder: a 31-phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1–3):354–61.

Wozniak J, Mick E, Waxmonsky J, et al. Comparison of open-label, 8-week trials of olanzapine monotherapy and topiramate augmentation of olanzapine for the treatment of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(5):539–45.

Hammerness P, Georgiopoulos A, Doyle R, et al. An open study of adjunct OROS-methylphenidate in children who are atomoxetine partial responders: II. Tolerability and pharmacokinetics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(5):493–9.

Calarge CA, Acion L, Kuperman S, et al. Weight gain and metabolic abnormalities during extended risperidone treatment in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(2):101–9.

Bahk WM, Shin YC, Woo JM, et al. Topiramate and divalproex in combination with risperidone for acute mania: a randomized open-label study. Prof Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(1):115–21.

Childress AC. Guanfacine extended release as adjunctive therapy to psychostimulants in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Adv Ther. 2012;29(5):385–400.

Penzner JB, Dudas M, Saito E, et al. Lack of effect of stimulant combination with second-generation antipsychotics on weight gain, metabolic changes, prolactin levels, and sedation in youth with clinically relevant aggression or oppositionality. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(5):563–73.

Daviss WB, Scott J. A chart review of cyproheptadine for stimulant-induced weight loss. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;41(1):65–73.

Safer D. Age-grouped differences in adverse drug events from psychotropic medication. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;21(4):299–309.

Jureidini J. Key opinion leaders in psychiatry: a conflicted pathway to career advancement. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46:495–7.

Cutting edge information. Key opinion leaders (PH122) relationship management and segmentation data. 2009 Extracts. http://www.cuttingedgeinfo.com/research/medical-affairs/key-opinion-leaders/. Accessed Feb 2012 (Full copy available from Jon Jureidini).

Allen S. Backlash on bipolar diagnoses in children: MGH psychiatrist’s work stirs debate. Boston Globe June 17, 2007. http://www.boston.com/yourlife/health/diseases/articles/2007/06/17/backlash_on_bipolar_diagnoses_in_children/.

Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):865–9.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank anonymous reviewers for careful analysis of earlier drafts of this paper.

No sources of funding were used to assist with the preparation of the review.

Conflicts of interest

Jon Jureidini, Anne Tonkin and Elsa Jureidini do not have any dualities of interest to declare. Jon Jureidini and Elsa Jureidini are members of Healthy Skepticism, an organisation that aims to counter misleading drug promotion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jureidini, J., Tonkin, A. & Jureidini, E. Combination Pharmacotherapy for Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Prevalence, Efficacy, Risks and Research Needs. Pediatr Drugs 15, 377–391 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-013-0032-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-013-0032-6