Abstract

Background

Understanding symptoms of temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs) can help doctors and patients document, monitor, and manage the disease and help researchers evaluate interventions. Patients with TMDs experience symptoms ranging from mild to severe, primarily in the head and neck region. This study describes findings from formative patient focus groups to capture, categorize, and prioritize symptoms of TMDs towards the development of a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM).

Methods

We conducted ten focus groups with 40 men and women with mild, moderate, and severe TMD. Focus groups elicited descriptions of symptoms and asked participants to review a list of existing patient-reported outcomes (PROs) from the literature and patient advisor input and speak to how those PROs reflect their own experience, including rating their importance.

Results

We identified 52 distinct concepts across six domains: somatic, physical, social, sexual, affective, and sleep. Focus groups identified the ability to chew and eat; clicking, popping, and other jaw noises; jaw pain and headaches; jaw misalignment or dislocation; grinding, clenching, or chewing, including at night; and ear sensations as most important. Participants with severe TMDs more often reported affective concepts like depression and shame than did participants with mild or moderate TMDs.

Conclusion

Findings support PROM item development for TMDs, including selecting existing PROMs or developing new ones that reflect patients’ lived experiences, priorities, and preferred terminology. Such measures are needed to increase understanding of TMDs, promote accurate diagnosis and effective treatment, and help advance research on TMDs.

Plain Language Summary

Patients with temporomandibular joint disorders, or TMDs, have pain and other problems in their jaw, and face and neck areas. We talked to 40 patients with mild, moderate, and severe TMDs to learn about their symptoms. We also asked patients to review a list of TMD symptoms. They then chose the most important ones based on their experience. The data showed 52 TMD symptoms and functions across six domains. The patients chose the ability to chew and eat; clicking, popping, and other jaw noises; and jaw pain and headaches as most important. They also chose jaw misalignment or dislocation; grinding, clenching, or chewing, including at night; and ear feelings as important. Findings support creating patient-reported outcome measures, or PROMs, for TMDs. These PROMs should reflect patients’ experiences and what is most important to them. Such measures can help doctors treat TMDs and help advance research on TMDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Researchers developing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs) may consider prioritizing symptoms and functions that were both identified as most important and mentioned across mild, moderate, and severe focus groups, including the following: the ability to chew and eat; clicking, popping, and other jaw noises; jaw pain and headaches; jaw misalignment or dislocation; grinding, clenching, or chewing, including at night; and ear sensations. |

Future development of PROMs for TMDs should consider attributes of symptoms and functions that are important to patients. Severity and predictability were often critical to participants’ experiences of painful or disruptive symptoms. PROMs should reflect patients’ chosen terminology, particularly items for physical symptoms. |

1 Introduction

Temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs) are disorders of the temporomandibular joints, jaw muscles, and facial nerves. Although TMDs are characterized by pain and disorder with the jaw, face, and teeth (e.g., jaw locking, tinnitus, bruxism), TMDs are not limited to the head and neck area [1] and are associated with chronic pain conditions across the body [2]. TMD symptoms can range from mild to severe, and when severe, TMDs can cause profound disability, distress, and disruption in people’s lives. For example, TMDs can make common activities such as eating, smiling, and kissing unendurable. Many patients with TMDs experience impacts in their social and personal lives (e.g., problems with mental health such as anxiety and depression) [1]. Furthermore, many patients with TMDs have difficulty obtaining adequate treatment and relief of symptoms [1] due to factors such as lack of high-quality research on TMD treatment [3], many clinicians’ and the public’s lack of understanding of the disease in general, and a lack of instruments with sufficient validation for measuring and evaluating TMDs and TMD treatment outcomes over time [1, 4].

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are patients’ reports of their health status in their own words, such as their symptoms or how well they are functioning [5]. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are standardized questionnaires and rating scales that can capture PRO information. Valid and reliable PROMs provide a systematic instrument to document and monitor disease, evaluate the safety and effectiveness of TMD therapies, and guide healthcare providers in patient care and disease management. Although a recent review identified more than 120 PROMs that have been used in TMDs research [6], few have robust evidence to support the reliability and validity of their scores [6]. For example, most did not include patient input in the content generation, and it was unclear whether they addressed the impacts of TMDs from the patients’ perspectives. Many of the PROMs were not specifically designed for use with patients with TMDs. They also lacked evidence of psychometric properties, such as measurement error and responsiveness [6].

Towards providing the formative research for developing a content-valid PROM for TMDs, we first conducted a systematic review of existing literature on PROMs for use in documenting treatment outcomes for TMDs (results presented elsewhere) [6]. This systematic review supported the need to conduct further qualitative research to understand TMDs from the patient’s point of view and contributed to the protocols used in this research. Then, we conducted patient focus groups to (1) identify concepts (i.e., patient-reported TMD symptoms and effects on functioning) that can be developed into PRO domains based on direct patient experience; and (2) assess their relative importance to patients. This article presents results of these focus groups, including the identified concepts by domain and self-reported severity.

2 Methods

We used focus groups, a qualitative research method, to address the research question. We report our findings using the COnsolidated Criteria for REporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) [7]. Below we describe our theoretical framework, participant selection, setting, data collection, and analyses. The overall study design and overview of the focus group discussions are illustrated in Figure 1.

2.1 Theoretical Approach

This study employed a phenomenological theoretical framework with grounded-theory data collection and analysis methods. This approach has been determined to yield PRO items and scales that have content validity by capturing patients’ authentic experiences [8]. Phenomenology is the study of people’s lived experiences; it therefore lends itself to the goal of understanding patients’ experiences of living with TMD symptoms. Grounded-theory methods provide the theoretical and practical underpinnings to capture patient experiences in their own words and to ensure adequate sample size to achieve thematic saturation [9, 10]. Together, these two theoretical approaches support both measure development and the evaluation of existing measures by permitting us to assess whether measures address domains that matter to patients and enable us to identify unique concepts related to living with TMDs.

2.2 Participant Selection

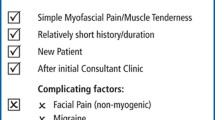

We partnered with a recruitment firm, whose medical director determined they had a robust enough group of individuals with TMD, to select and recruit participants through an online screening form and telephone confirmation. To obtain a diverse range of perspectives, concepts, and terminology during the interviews, we used purposive sampling to recruit English-speaking adult patients with a self-reported TMD diagnosis who varied by sex, age, race, ethnicity, geographic location, education level, employment status, time since diagnosis, and disease severity. We limited the number of participants with advanced levels of education or experience working in clinical care to no more than two participants from either category per focus group so that those perspectives would not bias or dominate the conversations and to limit the amount of jargon in the transcripts. Disease severity was determined by participants’ responses to the 5-item Short-Form Fonseca Anamnestic Index, in accordance with a pre-determined severity scale [11, 12]. Responses were scored (0 for no, 5 points for sometimes, 10 points for yes), and total scores were used to classify symptoms and effects on functioning as mild (10–20 points), moderate (25–35 points), or severe (40–50 points). Respondents with scores of 0 or 5 were considered ineligible and therefore not invited to participate in the study.

2.3 Setting

Due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, we conducted the focus groups virtually using the Zoom video conferencing platform. The recruitment firm provided participants with background information about the focus group purpose and format prior to each group. We held focus groups in a secure virtual meeting room with the participants, facilitator, and notetaker. Participants were encouraged to turn on their video during the focus groups to facilitate communication via non-verbal cues, but they were given the option not to appear on video if they did not feel comfortable doing so.

We organized ten focus groups by TMD disease severity (three mild, three moderate, and four severe groups) to ensure participant comfort, and provide participants with severe TMD with the opportunity to give more in-depth feedback on their symptoms and quality of life. While the mild and moderate severity groups were gender heterogenous, the four severe TMD groups were gender homogenous (two male-only and two female-only groups). Since more severe symptoms may have a greater impact on aspects of life that may be sensitive in nature (e.g., sexual activity or intimacy), we organized gender homogenous groups to provide a more comfortable environment for participants to share their experiences and perspectives.

2.4 Data Collection

We conducted ten, 1-h focus groups with three to five participants in each group (a total of 40 participants) in July and August of 2021. We also conducted a phone interview in August 2021 with a participant with severe TMD who, after participating in a focus group, asked to share additional comments in a one-on-one setting.

Trained focus group facilitators (TCO [female, with a Master of public policy] and a male facilitator with a Ph.D. in health communication who is not an author) conducted each group with support from a notetaker (DL). At the time of this study, both facilitators were health researchers trained in qualitative methods with several years of experience applying those methods to data collection and analysis. Neither facilitator had relationships with any study participants. Participants did not know anything about the research or researchers prior to the focus group. The facilitators had no previous personal experience with TMDs or other personal experiences that might bias their approach toward the topic or participants. The facilitators introduced themselves at the onset of the focus group by name and profession and the organization where they were employed. Facilitators used a focus group discussion guide to promote an open discussion of patients’ experiences with their disease, review with patients the preliminary list of symptoms and functions generated by the systematic review and patient advisor input (see Appendix A, “Focus Group Discussion Guide,” see the electronic supplementary material) [6], and obtain participant guidance on prioritizing symptoms. The facilitator then prompted participants to consider the list of symptoms and effects on functioning, as well as any others participants experienced that were not on the list, and to share their top five most important ones in terms of impact on the quality of their lives. After sharing their top five, participants were asked to come to a consensus on which symptoms were the most important. The discussion guide (Appendix A) was pilot tested using a mock focus group comprising participants with TMDs.

Each focus group discussion was video-recorded and transcribed for analysis. The notetaker completed field notes used for rapid-cycle analysis to inform updates to the symptom list for subsequent focus groups.

2.5 Data Coding and Analysis

We coded and analyzed the focus group data following the recommendations for qualitative research set forth by experts in PRO development and validation [7, 13,14,15]. For the purposes of analysis, we treated data from the additional one-on-one interview we conducted as part of the focus group in which the participant originally participated. We coded data using NVivo Pro12 qualitative analysis software. We created a preliminary coding dictionary based on the TMD-relevant PROs found in our systematic review [6]. However, we coded data using an open-coding method, adding new codes to the dictionary as needed to reflect the identified concepts. This approach reduced the risk of missing unique content discussed in the transcripts [8, 16].

To assess and optimize coding reliability and minimize bias, two analysts (DL, EM) coded the first focus group transcript separately and then jointly reviewed their coding with each other and with a senior analyst (EE) to achieve consensus and resolve any discrepancies. We used NVivo to calculate inter-coder agreement (ICA) for this focus group and achieved over 90% agreement. Because the first average ICA was above the threshold generally considered to be an appropriate goal for ICA (> 80%), one analyst coded each of the remaining focus group transcripts [17].

Two analysts (DL, EM) separately identified concepts and organized codes into predefined categories based on content and context with oversight from a senior analyst (EE). We determined that we had reached thematic saturation, or the point at which no, or few new concepts were identified from the data [10, 18], by tracking the identification of concepts across focus groups. Over half of the concepts were identified from the first two focus groups we conducted, which were mild and moderate TMD focus groups, respectively (see Appendix B, see the electronic supplementary material). No new concepts were identified from the last focus group (a severe TMDs focus group); therefore, we concluded that we had reached thematic saturation and determined that we need not conduct additional focus groups.

We assigned “attribute” codes to concepts as appropriate when participants’ comments addressed the frequency, severity, predictability, or fluctuation of symptoms (i.e., the ways in which symptoms and functions went away, then came back over discrete periods of time). For example, the severity code was applied to comments when participants described the severity of their symptoms, or the degree to which symptoms were tolerable versus painful, uncomfortable, or debilitating.

In our analysis, we aimed to explore relationships between discrete terms and concepts, rather than simply to label them. For example, analysts noticed a pattern of descriptions that permitted a distinction to be made between participants’ abilities to fulfill different types of social roles (e.g., role as a professional worker or student versus a role as a family member, friend, or romantic partner). The analysts then reviewed their work together to identify and reconcile differences. Once concepts were identified, we developed definitions and identified exemplar quotes to model each (see Appendix C, see the electronic supplementary material).

3 Results

3.1 Participants

Forty adults with TMDs participated in ten focus groups (54 patients recruited, four cancellations, and ten no-shows). Most participants were between 25 and 66 years old (65%), held at least a bachelor’s degree (79%), were female (65%), were white (60%), and were non-Hispanic (83%). Table 1 displays participant characteristics by disease severity.

3.2 Focus Group Results

3.2.1 Concepts

Appendix C (see the electronic supplementary material) includes a table showing the 52 concepts identified from our analysis of the focus group data, as well as definitions and exemplar quotes for each concept. The concepts spanned six categories: somatic (n = 27 concepts) (e.g., pain, jaw clicking or popping, stiffness, inflammation); physical function (n = 9 concepts) (e.g., ability to eat, talk, or open the mouth); emotional affective (n = 8 concepts) (e.g., anxiety, stress, depression, embarrassment or shame); social function (n = 4 concepts) (e.g., impact on social activities, ability to fulfill social roles); sleep quality (n = 3 concepts) (e.g., ability to sleep, restfulness); and sexual function (n = 1 concept) (sexual activity).

PROMs often address attributes of symptoms and functions to capture their severity, predictability, frequency, and fluctuation when those attributes are relevant to patients. Participants most often referenced the severity of symptoms and functions when describing pain. Participants most often discussed predictability when describing the degree to which they could anticipate when symptoms or effects on functioning would occur. Participants were especially bothered when they were not able to predict when symptoms – especially pain, jaw locking, and jaw noises – would occur or be the most severe (e.g., at night or during certain weather conditions). Participants tended to discuss frequency, which is the rate of occurrence of symptoms. Participants also generally discussed wax and wane regarding the ways in which symptoms went away, then came back over discrete periods of time, as opposed to in relation to specific symptoms or timeframes.

3.2.2 Most Important Symptoms and Functions

Table 2 shows the identification of symptoms and functions labeled by focus group members as “most important to quality of life.” Symptoms and functions that were mentioned in at least seven of the ten focus groups included the following: ability to chew; clicking, popping, or other jaw noises; headache; jaw misalignment or dislocation; jaw pain; ability to eat; and neck pain. Ear sensations; grinding, clenching, or chewing, including at night; and facial pain were identified as most important in at least five of the ten focus groups.

3.2.3 Stratification of concepts by TMD severity

Table 3 displays a heat map of the number of focus groups in which each concept was mentioned by TMD severity. Concepts that were commonly mentioned (i.e., in ≥ 2 focus groups) across all three types of focus group (mild, moderate, severe) included the following: ability to chew; ability to eat; ability to open mouth; impact on relationships; ability to fill social roles; jaw pain; headache; migraine; ear sensations; soreness; grinding, clenching, or chewing, including at night; mouth changes; jaw misalignment or dislocation; jaw locking; and clicking, popping, or other jaw noises.

Focus groups with participants with severe TMDs reported the following concepts more often than in mild or moderate TMD participant groups (as indicated by a ≥ 2 focus group difference between participants with severe and mild or moderate TMDs in terms of the number of times a concept was mentioned): depression; annoyance or irritability; embarrassment/shame; ability to eat; ability to yawn; sexual activity; restfulness; jaw pain; jaw muscle tension or tightness, including in the face and neck; changes to facial muscles, including atrophy and paralysis; and vertigo.

There were no concepts that were unique to only participants with mild or moderate TMDs, but there were some that were unique to participants with severe TMDs; these included the following: ability to play an instrument; changes to facial muscles, including atrophy and paralysis; vertigo; and hoarseness.

4 Discussion

This study identified 52 concepts across six domains (somatic, physical, social, sexual, affective, and sleep) pertaining to the participants’ experiences with TMDs. The concepts that focus groups most commonly identified as most important to their quality of life across mild, moderate, and severe TMD focus groups included the ability to chew and eat; clicking, popping, and other jaw noises; jaw pain and headaches; jaw misalignment or dislocation; grinding, clenching, or chewing, including at night; and ear sensations. Severe TMD focus groups more often identified affective symptoms—including depression, annoyance or irritability, and embarrassment or shame—than did mild or moderate focus groups, suggesting that mental health challenges may increase commensurate with TMD severity. Some of the concepts identified were not included in PROMs used in the study of TMDs, including mouth changes, jaw tightness/tension, ear sensations, and jaw locking [6]. Additionally, many of the concepts measured by existing PROMs were spread across different PROMs with different scoring systems, limiting the types of conclusions that could be drawn from them [6].

Findings from this study align with existing literature describing common symptoms and effects on functioning among patients with TMDs. Like our study, past studies have found that patients with TMDs report somatic symptoms such as involuntary grinding, clenching, or chewing [19,20,21,22,23,24], jaw pain [25], jaw misalignment or dislocation, jaw noises including clicking and popping [25,26,27,28,29,30], headaches [31,32,33], and ear sensations, such as tinnitus [34,35,36], and deficits in physical function, such as the ability to eat and chew [20, 22]. As in our study, affective symptoms including depression and anxiety were particularly prevalent among patients with TMD, especially among those with severe TMDs [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], as were effects on social function (e.g., restrictions in social interactions due to shame or embarrassment) [45], sleep quality [46,47,48], and sexual function (e.g., loss of sexual interest) [49].

Past studies have examined symptom prevalence [50,51,52], comorbidities with TMDs and how they worsen pain [27, 35, 53,54,55], and symptom intensity among different subgroups of patients with TMD [21]. Studies of symptom severity have focused on efficacy of treatment [56, 57]. Our study is distinguished in its goal to prioritize patients’ experiences of their symptoms and functioning and how patients experience TMD differently by different severity levels. Future research could build upon our study’s findings to further prioritize those symptoms and functions that are considered most important to patients with TMD, which can help target treatments and interventions to the patient experience.

The study had some limitations. First, many focus group participants raised issues with their treatments, care delivery, or provider behavior. As these topics are specific to health care delivery and not specific to a description of health outcomes, they are beyond the scope of a PROM, and therefore we did not include these comments in our analysis [58, 59]. Second, participants’ TMD diagnoses were self-reported, which introduces the potential for misclassification. However, clinical diagnoses also can misclassify patients. Current diagnostic classification systems for TMDs are limited due to their lack of epidemiological data for incidence and persistence of TMD, and by the lack of coherence between classification criteria and definition of the disorder [1]. For the purposes of this study, we used the Fonseca Index to classify patients into mild, moderate, and severe strata. While studies support the validity and reliability of this measure [11, 12], the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine recognizes the need for continued research to better characterize the degree of severity of TMDs [1]. Third, our unit of analysis was the focus group, and, therefore, our study presents findings at the level of the focus group, not the individual. Individual variation in experience with TMDs, such as differences between experiences of individuals with pain-related versus intra-articular TMDs, may not be well represented by the unit of analysis. Fourth, data collection took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we conducted virtual focus groups. This approach had drawbacks, such as technical difficulties experienced by some participants. However, the virtual approach was effective at eliciting patient symptoms and may have had some benefits over in-person groups, such as, a sense of anonymity and less social pressure on sensitive topics [60]. Finally, we convened gender homogeneous focus groups to help participants feel comfortable discussing their TMD symptoms and effects on functioning. However, at least one participant that we are aware of did not feel comfortable discussing TMD symptoms related to sexual function within the gender homogenous setting. Individual interviews may be a more effective way to elicit patient experiences related to TMDs and sexual function.

Findings from our study may inform the future selection or development and prioritization of PROMs and PROM items for TMDs. For example, to capture the breadth of patients’ experiences, PROMs for TMDs could address the six concept categories (i.e., somatic symptoms, physical function, emotional affective symptoms, social function, sleep quality, and sexual function). Alternatively, those who wish to evaluate targeted aspects of TMDs may draft PROM items for a particular concept category such as somatic symptoms. Researchers developing PROMs for TMDs may also wish to prioritize symptoms and functions that were both identified as most important in more than half of focus groups and mentioned across all three types of focus groups (i.e., mild, moderate, and severe). In addition, PROMs for TMDs should reflect attributes of the symptom or functional deficit (i.e., concept) that are important to patients. In particular, the attributes of severity and predictability were often critical to participants’ experiences of certain symptoms. The attribute of severity was almost always discussed when describing pain, and predictability was especially important to patients in relation to debilitating, jarring, or inconveniencing symptoms, such as jaw locking or jaw noises like clicking. Lastly, PROM items should take patients’ temporal experience of TMDs into account. For example, symptoms may vary in frequency for different patients and may come and go, such that it may be most productive to ask about the time when symptoms were worst, as opposed to how symptoms are right now.

In future development of PROM items, cognitive testing with patients with TMD to elicit information about proposed PROM item comprehensibility and relevance (e.g., towards updating or adapting items) should consider patients’ preferred terminology when speaking about their TMD symptoms. For example, terminology used to describe somatic symptoms such as those of the jaw (e.g., popping, clicking, locking), ear (e.g., fullness, popping, ringing, thumping, throbbing), or teeth (e.g., grinding, chewing, clenching) may have distinct meanings to patients that reflect meaningful differences in the patient experience and should be carefully chosen. In addition, pain may reflect differences (e.g., in severity) that are meaningful for patients and may have different implications for symptom management and health outcomes.

5 Conclusion

Data from reliable and valid PROM instruments would increase understanding of TMDs, promote accurate diagnosis and effective treatment, and help advance research and the development of meaningful interventions. While many PROMs have been used in TMD research, they lack comprehensive and robust evidence of their ability to assess the effectiveness of TMD treatment with validity and reliability [6]. Particularly lacking is evidence based on patient input to support the content validity of TMD PROMs [6]. Using a systematic approach, we conducted the formative research to support PROM item development for TMDs. Findings provide the groundwork for selecting or augmenting existing PROMs or developing new ones that reflect patients’ lived experiences, priorities, and preferred language [6]. Additional research is warranted to develop, cognitively test, and evaluate the psychometric properties and underlying structure of PROMs for TMDs. Further refinement of PROM items, for example by prioritizing those most meaningful and impactful to patients, can help produce PROMs that are more accurate, relevant, and appropriate for use in the healthcare setting.

References

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Temporomandibular disorders: priorities for research and care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2020.

Slade GD, Greenspan JD, Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Sharma S, Ohrbach R. Overlap of five chronic pain conditions: temporomandibular disorders, headache, back pain, irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2020;34:s15–28.

List T, Axelsson S. Management of TMD: evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(6):430–51.

Ohrbach R, Greene C. Commentary on Temporomandibular Disorders: Priorities for Research and Care: State-of-the-science for both general dentists and specialists. J Ame Dent Assoc (1939. 2022;153(4):295-7.e3.

US Food and Drug Administration-National Institutes of Health Biomarker Working Group. BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools) resource. Silver Spring: Food and Drug Administration (US), National Institutes of Health (US); 2016.

Keller S, Bocell FD, Mangrum R, McLorg A, Logan D, Chen A, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for individuals with temporomandibular joint disorders: a systematic review and evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radioly. 2023;135(1):65–78.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, Abetz L, Arnould B, Bayliss M, et al. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(8):1087–96.

Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 1999.

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–907.

Fonseca DM, Bonfante G, Valle AL, de Freitas SFT. Diagnósticopela anamnese da disfunc¸ão craniomandibular. Rev Gauch deOdontol. 1994;4(1):23–32.

Rodrigues-Bigaton D, de Castro EM, Pires PF. Factor and Rasch analysis of the Fonseca anamnestic index for the diagnosis of myogenous temporomandibular disorder. Braz J Phys Ther. 2017;21(2):120–6.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: Methods to identify what is important to patients: Guidance for industry, Food and Drug Administration staff, and other stakeholders: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/131230/download. Accessed 23 May 2022.

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, et al. Content validity–establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2–assessing respondent understanding. Value Health. 2011;14(8):978–88.

Rothman M, Burke L, Erickson P, Leidy NK, Patrick DL, Petrie CD. Use of existing patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments and their modification: the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Evaluating and Documenting Content Validity for the Use of Existing Instruments and Their Modification PRO Task Force Report. Value Health. 2009;12(8):1075–83.

Birks M, Mills J. Grounded theory: A practical guide. 2nd ed. London, UK: Sage Publications; 2015.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994.

Urquhart C. Grounded theory for qualitative research: a practical guide. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2013.

Blanco Aguilera A, Gonzalez Lopez L, Blanco Aguilera E, De la Hoz Aizpurua JL, Rodriguez Torronteras A, Segura Saint-Gerons R, et al. Relationship between self-reported sleep bruxism and pain in patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41(8):564–72.

Brandini DA, Benson J, Nicholas MK, Murray GM, Peck CC. Chewing in temporomandibular disorder patients: an exploratory study of an association with some psychological variables. J Orofac Pain. 2011;25(1):56–67.

Karibe H, Goddard G, Kawakami T, Aoyagi K, Rudd P, McNeill C. Comparison of subjective symptoms among three diagnostic subgroups of adolescents with temporomandibular disorders. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2010;20(6):458–65.

Marim GC, Machado BCZ, Trawitzki LVV, de Felício CM. Tongue strength, masticatory and swallowing dysfunction in patients with chronic temporomandibular disorder. Physiol Behav. 2019;210: 112616.

Shedden Mora M, Weber D, Borkowski S, Rief W. Nocturnal masseter muscle activity is related to symptoms and somatization in temporomandibular disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73(4):307–12.

Su N, Liu Y, Yang X, Shen J, Wang H. Association of malocclusion, self-reported bruxism and chewing-side preference with oral health-related quality of life in patients with temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Int Dent J. 2018;68(2):97–104.

Poluha RL, De la Torre CG, Bonjardim LR, Conti PCR. Somatosensory and psychosocial profile of patients with painful temporomandibular joint clicking. J Oral Rehabil. 2020;47(11):1346–57.

Bilgiç F, Gelgör İE. Prevalence of temporomandibular dysfunction and its association with malocclusion in children: an epidemiologic study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2017;41(2):161–5.

Dahan H, Shir Y, Velly A, Allison P. Specific and number of comorbidities are associated with increased levels of temporomandibular pain intensity and duration. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:528.

Iodice G, Cimino R, Vollaro S, Lobbezoo F, Michelotti A. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder pain, jaw noises and oral behaviours in an adult Italian population sample. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(8):691–8.

Mustafa R, Güngörmüş M, Mollaoğlu N. Evaluation of the efficacy of different concentrations of dextrose prolotherapy in temporomandibular joint hypermobility treatment. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29(5):e461–5.

Slade GD, Sanders AE, Bair E, Brownstein N, Dampier D, Knott C, et al. Preclinical episodes of orofacial pain symptoms and their association with health care behaviors in the OPPERA prospective cohort study. Pain. 2013;154(5):750–60.

Costa YM, Alves da Costa DR, de Lima Ferreira AP, Porporatti AL, Svensson P, Rodrigues Conti PC, et al. Headache exacerbates pain characteristics in temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Fac Pain Headache. 2017;31(4):339–45.

List T, John MT, Ohrbach R, Schiffman EL, Truelove EL, Anderson GC. Influence of temple headache frequency on physical functioning and emotional functioning in subjects with temporomandibular disorder pain. J Orofac Pain. 2012;26(2):83–90.

Miller VJ, Karic VV, Ofec R, Nehete SR, Smidt A. The temporomandibular opening index, report of headache and TMD, and implications for screening in general practice: an initial study. Quint Int. 2014;45(7):605–12.

Lacerda AB, Facco C, Zeigelboim BS, Cristoff K, Stechman JN, Fonseca VR. The impact of tinnitus on the quality of life in patients with temporomandibular dysfunction. Int Tinnitus J. 2016;20(1):24–30.

Maciel LFO, Landim FS, Vasconcelos BC. Otological findings and other symptoms related to temporomandibular disorders in young people. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;56(8):739–43.

Mejersjö C, Näslund I. Aural symptoms in patients referred for temporomandibular pain/dysfunction. Swed Dent J. 2016;40(1):13–20.

Bertoli E, de Leeuw R. Prevalence of suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety in chronic temporomandibular disorder patients. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2016;30(4):296–301.

Hirsch C, Türp JC. Temporomandibular pain and depression in adolescents–a case-control study. Clin Oral Invest. 2010;14(2):145–51.

Ismail F, Eisenburger M, Lange K, Schneller T, Schwabe L, Strempel J, et al. Identification of psychological comorbidity in TMD-patients. Cranio. 2016;34(3):182–7.

Manfredini D, Winocur E, Ahlberg J, Guarda-Nardini L, Lobbezoo F. Psychosocial impairment in temporomandibular disorders patients RDC/TMD axis II findings from a multicentre study. J Dent. 2010;38(10):765–72.

Mingarelli A, Casagrande M, Di Pirchio R, Nizzi S, Parisi C, Loy BC, et al. Alexithymia partly predicts pain, poor health and social difficulties in patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2013;40(10):723–30.

Sebastiani AM, Dos Santos KM, Cavalcante RC, Pivetta Petinati MF, Signorini L, Antunes LAA, et al. Depression, temporomandibular disorders, and genetic polymorphisms in IL6 impact on oral health-related quality of life in patients requiring orthognathic surgery. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(12):3315–23.

Tay KJ, Yap AU, Wong JCM, Tan KBC, Allen PF. Associations between symptoms of temporomandibular disorders, quality of life and psychological states in Asian Military Personnel. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(4):330–9.

Yeung E, Abou-Foul A, Matcham F, Poate T, Fan K. Integration of mental health screening in the management of patients with temporomandibular disorders. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;55(6):594–9.

Taimeh D, Leeson R, Fedele S, Ni RR. A meta-synthesis of qualitative data exploring the experience of living with temporomandibular disorders: the patients’ voice. Oral Surg. 2022;00:1–17.

Benoliel R, Zini A, Zakuto A, Slutzky H, Haviv Y, Sharav Y, et al. Subjective sleep quality in temporomandibular disorder patients and association with disease characteristics and oral health-related quality of life. j Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2017;31(4):313–22.

Quartana PJ, Wickwire EM, Klick B, Grace E, Smith MT. Naturalistic changes in insomnia symptoms and pain in temporomandibular joint disorder: a cross-lagged panel analysis. Pain. 2010;149(2):325–31.

Rener-Sitar K, John MT, Pusalavidyasagar SS, Bandyopadhyay D, Schiffman EL. Sleep quality in temporomandibular disorder cases. Sleep Med. 2016;25:105–12.

Pihut M, Krasińska-Mazur M, Biegańska-Banaś J, Gala A. Psychoemotional disturbance in adult patients with temporomandibular disorders Research article. Folia Med Cracov. 2021;61(1):57–65.

Kotiranta U, Suvinen T, Kauko T, Le Bell Y, Kemppainen P, Suni J, et al. Subtyping patients with temporomandibular disorders in a primary health care setting on the basis of the research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders axis II pain-related disability: a step toward tailored treatment planning? J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2015;29(2):126–34.

Mobilio N, Casetta I, Cesnik E, Catapano S. Prevalence of self-reported symptoms related to temporomandibular disorders in an Italian population. J Oral Rehabil. 2011;38(12):884–90.

Svedström-Oristo AL, Ekholm H, Tolvanen M, Peltomäki T. Self-reported temporomandibular disorder symptoms and severity of malocclusion in prospective orthognathic-surgical patients. Acta Odontol Scand. 2016;74(6):466–70.

Silveira A, Gadotti IC, Armijo-Olivo S, Biasotto-Gonzalez DA, Magee D. Jaw dysfunction is associated with neck disability and muscle tenderness in subjects with and without chronic temporomandibular disorders. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015: 512792.

Skog C, Fjellner J, Ekberg E, Häggman-Henrikson B. Tinnitus as a comorbidity to temporomandibular disorders-A systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(1):87–99.

Tosato JP, Politti F, Santos-Garcia MB, Oliveira-Gonzalez T, Biasotto-Gonzalez DA. Correlation between temporomandibular disorder and quality of sleep in women. Fisioterapia em Movimento. 2016;29(3):527–31.

Saueressig AC, Mainieri VC, Grossi PK, Fagondes SC, Shinkai RS, Lima EM, et al. Analysis of the influence of a mandibular advancement device on sleep and sleep bruxism scores by means of the BiteStrip and the Sleep Assessment Questionnaire. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23(3):204–13.

Selvam PS, Ramachandran RS. A comparative study on the effectiveness of manipulative technique and conservative physiotherapy modalities in correction of Temporo-mandibular Joint Disorder. Indian J Physiother Occup Therapy. 2017;11:195.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry-patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2009. https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download. Accessed 23 May 2022.

International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL) Dictionary of Quality of Life and Health Outcomes Measurement. Mayo NE, editor. 1st edn. Milwaukee: ISOQOL; 2015.

Litosseliti L. Using focus groups in research. Bloomsbury Publishing; 2003.

Acknowledgements

The Funding for this study was provided by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The study was funded by the FDA.

Conflict of interest

No authors have conflicts of interest to report.

Ethics approval

Before any study procedures were initiated, the study was approved by the American Institutes for Research’s Institutional Review Board (AIR’s IRB) (Arlington, VA, USA) (institutional review board reference number #8A145). AIR’s IRB (IRB00000436) has conducted expedited and full-board reviews of research involving human subjects for more than 23 years, is registered with the Office of Human Research Protection as a research institution (IORG0000260), and conducts research under its own Federalwide Assurance (FWA00003952). This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments and is reported in accordance with the recommendations of the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) checklist.

Consent to participate

All participants provided verbal and online consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as no consent was sought from participants to allow sharing of data with third parties.

Author contributions

EE, TCO, DL, EM, and CV (AIR) contributed to material preparation, data collection and analysis, and drafting and editing the manuscript. SK (AIR) contributed to study conceptualization, study design, material preparation, funding acquisition, and editing the manuscript. All authors from the FDA and TMJ Association contributed to study design and material preparation and reviewed and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elstad, E., Bocell, F.D., Owens, T.C. et al. Focus Groups to Inform the Development of a Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (PROM) for Temporomandibular Joint Disorders (TMDs). Patient 16, 265–276 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-023-00618-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-023-00618-x