Abstract

Background and Objective

Children with inherited metabolic diseases often require complex and highly specialized care. Patient and family-centered care can improve health outcomes that are important to families. This study aimed to examine experiences of family caregivers (parents/guardians) of children diagnosed with inherited metabolic diseases with healthcare to inform strategies to improve those experiences.

Methods

A cross-sectional mailed survey was conducted of family caregivers recruited from an ongoing cohort study. Participants rated their healthcare experiences during their child’s visits to five types of healthcare settings common for inherited metabolic diseases: the metabolic clinic, the emergency department, hospital inpatient units, the blood laboratory, and the pharmacy. Participants provided narrative descriptions of any memorable negative or positive experiences.

Results

There were 248 respondents (response rate 49%). Caregivers were generally very or somewhat satisfied with the care provided at each care setting. Appropriate treatment, provider knowledge, provider communication, and care coordination were deemed essential aspects of satisfaction with care by the majority of participants across many settings. Memorable negative experiences were reported by 8–22% of participants, varying by setting. Among participants who reported memorable negative experiences, contributing factors included providers’ demeanor, lack of communication, lack of involvement of the family, and disregard of an emergency protocol letter provided by the family.

Conclusions

While caregivers’ satisfaction with care for children with inherited metabolic diseases was high, we identified gaps in family-centered care and factors contributing to negative experiences that are important to consider in the future development of strategies to improve pediatric care for inherited metabolic diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This study identifies several elements of care that contribute to parents’ satisfaction with healthcare across five healthcare settings commonly visited by children with inherited metabolic diseases (IMD), including receipt of appropriate treatment, provider knowledge and communication, and coordinated care. |

While generally satisfied with care, parents of children with IMD reported recent memorable negative experiences with their child’s healthcare, particularly in the emergency department and during hospitalization. These negative experiences were often related to poor provider demeanor, lack of communication, poor involvement of the family, and disregard of emergency protocol letters. |

Our findings provide an important foundation for understanding where gaps in family-centered healthcare are for children with IMD, informing the development of interventions and strategies to address those gaps and ultimately improve healthcare for children with IMD. |

1 Background

Inherited metabolic diseases (IMD) are a group of rare single-gene diseases frequently diagnosed early in life that have a collective prevalence of approximately 50.9 per 100,000 live births [1]. Children with IMD often require complex and specialized care [2,3,4]. Across a variety of diseases, settings, and patient populations, patient experience with care is associated with clinical and safety outcomes [5] and is recognized as key to a high-quality health system [6]. Principles of patient-centered care, including accessible services, respect, clear communication, and coordination and continuity of care [7,8,9], often form the basis of assessments of patient experience [10]. In pediatrics, the concept of patient-centered care is extended to family-centered care, emphasizing children’s developmental needs and the central role of families [11, 12].

Aspects of healthcare shown to be important to the experiences of children with chronic conditions and their families include care coordination [11,12,13] and perceived empathy of healthcare providers [14]. However, few studies have examined healthcare experiences for children with IMD specifically [15,16,17,18]. In our previous qualitative study in this population, while parents/guardians reported positive care experiences within the pediatric metabolic clinic, they often expressed dissatisfaction with care in non-IMD-specific healthcare settings, such as the pharmacy, emergency department, and blood laboratory. These negative experiences tended to stem from interactions with providers unfamiliar with a child’s diagnosis and/or coordination and communication of services [17]. To better understand and inform strategies to improve care, this study examines experiences with healthcare among a larger sample of children diagnosed with IMD from the perspectives of their caregivers.

2 Methods

2.1 Ethical Considerations

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Boards of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa Health Science Network and participating centers.

2.2 Participants and Study Design

Participants were parents or guardians (“caregivers”, one per household) recruited from an ongoing cohort study of children born between 2006 and 2015 with a confirmed diagnosis of one of 31 IMD (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]), receiving treatment from one of 13 participating pediatric metabolic clinics, all located at major Canadian hospitals. Caregivers who had agreed to be re-contacted for research were eligible to participate. Between 20 January, 2017 and 18 July, 2018, participants were invited to complete a one-time cross-sectional questionnaire. Participants with multiple children in the cohort were invited to complete the survey for their oldest child in the cohort. All eligible families were contacted by mail up to four times using an approach adapted from Dillman [19]: they were mailed a pre-notification letter to inform them of the study, an invitation to participate along with the questionnaire, and two reminder messages with replacement questionnaires. Consent was implied with completion and return of the questionnaire by mail, in pre-paid envelopes.

2.3 Questionnaire Development

Questionnaire content and instrument selection were informed by previous qualitative studies [17, 20] and a scoping review [21]. Minor changes to the questionnaire were made following a pilot test with six parents of children with an IMD using cognitive telephone interviews [22], whereby participants answered the questionnaire by verbally describing their thought process.

2.4 Measures

2.4.1 Child and Family Characteristics

We collected data on participant and household-level characteristics, such as annual gross household income, home community size, gender identity, relationship to the child, employment status, and attained education. Child’s sex, birth year, and IMD were linked from the cohort study. We also collected data on typical mode of travel and travel time from a participant’s home to the metabolic clinic.

2.4.2 Care Experiences

Participants were asked how many times, in the past year, they had visited each of five healthcare settings for their child’s care: metabolic clinic, blood laboratory, emergency department, hospitalizations, and pharmacy. For each setting visited at least once, participants were asked to rate their overall satisfaction with care on a five-point scale, from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied”. Participants then selected factors that they considered essential to their satisfaction rating from a list of options tailored to each setting. Next, participants were asked, “In the past year, have you had an experience at [setting] for your child’s care that was either so positive or so negative, you were still thinking about it one week later?”. If “yes”, participants indicated whether the experience was positive or negative, and were invited to provide a brief narrative description of that experience.

We measured caregiver perceptions of care coordination for their child by adapting the Family Experiences with Care Coordination Survey [23]. Participants were asked to identify the provider they considered to be their child’s main provider, defined as the person “who knows the most about your child’s health, and who is in charge of your child’s care overall,” and then asked questions related to their experiences with: getting help to manage their child’s care; care from specialists and receipt of community services; and visit summaries and care plans.

The metabolic clinic plays a significant role in the healthcare of most children with an IMD. We measured participants’ perceptions of the overall care that their child received at the metabolic clinic over the previous year using the validated Measures of Processes of Care (MPOC-20) instrument [24]. The MPOC-20 assesses the extent to which healthcare services are family centered and consists of five subscales: enabling and partnerships; providing general information; providing specific information; coordinated and comprehensive care; and respectful and supportive care. Scores range from 1 to 7 with higher scores indicating that a provider or clinic exhibits a behavior/activity to a greater extent.

2.5 Data Analysis

We entered survey data in duplicate and compared entries; differences were resolved by consensus. Survey data were stored using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) [25, 26] and analyzed using Microsoft Excel and SAS software (Version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, USA).

Analyses were primarily descriptive. Data for three variables were grouped during analysis (Table 1). We calculated proportions for categorical variables and medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. We used an inductive process to code narrative descriptions for the aspects of care that contributed to participants’ memorable experiences. Briefly, one author (MP) reviewed the narrative data and assigned codes to each description, and a second author (AC) verified the coding. AC, MP, and BKP collaborated to group the codes into higher order themes.

We also conducted exploratory post-hoc stratified analyses to describe satisfaction with care at each setting by: community size (larger vs smaller); child age group (≥ 5 vs < 5 years); and visit frequency. We stratified by community size given the well-known barriers associated with access to specialist care in rural areas [27, 28]. We stratified by child age given the different healthcare needs at different ages, which we reasoned could have an important impact on family experiences. Finally, we speculated that more frequent visitors may be more familiar with a setting and able to navigate concerns more easily, but also that negative experiences may accumulate with visit frequency. We calculated 95% confidence intervals for each proportion but, given their post-hoc nature and the number of stratifications and settings, we did not conduct hypothesis tests for these exploratory analyses. For the metabolic clinic, we used non-parametric tests of significance (Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis test) to investigate differences in MPOC-20 scores associated with satisfaction with care at the metabolic clinic (satisfied vs non-satisfied), community size, and travel time to the clinic (categories from < 30 min to > 2 h). Because of small numbers, we did not analyze satisfaction by IMD. However, as a sensitivity analysis, we described satisfaction with care among a subgroup of participants whose children received care at four to five healthcare settings, as a proxy for high healthcare needs. We also conducted a post-hoc descriptive analysis of satisfaction with care by memorable positive or negative experiences. Missing data were minimal (< 3%) and were handled using casewise deletion.

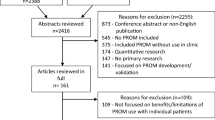

3 Results

At the time of study recruitment, 536 children had been enrolled in the cohort study. Valid mailing addresses and consent to be re-contacted for future studies were available for 509 children; their caregivers were invited to participate in the survey. Of those invited, 248 caregivers completed and returned questionnaires, a response rate of 49%. Children of survey respondents were similar to the full cohort in sex, age, and IMD (data not shown). Most questionnaires (84%) were completed by a female biological parent (Table 2). Nearly half of participants (48%) reported traveling 1 hour or more to reach the clinic. Close to half of the children were diagnosed with either medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (23%) or phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency (23%).

3.1 Satisfaction with Care

Most participants visited the metabolic clinic (n = 230, 93%), a hospital or community-based blood laboratory (n = 208, 84%), or a pharmacy (n = 174, 70%) at least once in the previous year for their child’s care. A minority visited the emergency department (n = 80, 32%) or were hospitalized (n = 46, 19%).

Satisfaction with care was generally high among participants (Table 3), with ratings from 78 to 84% satisfied at the metabolic clinic, pharmacy, and blood laboratory. A slightly smaller proportion of participants were satisfied with care provided during hospitalization (n = 32, 70%) and at the emergency department (n = 55, 69%). The proportion of participants satisfied with care at the metabolic clinic was somewhat smaller among those living in smaller (n = 49, 77%) vs larger (n = 143, 88%) communities. While there were also differences across strata based on community size and visit frequency at the emergency department and during hospitalization, these exploratory analyses were based on small numbers.

3.2 Contributors to Satisfaction Ratings

Providers’ attitudes and communication with families were rated as essential or very important to levels of satisfaction with care by ≥ 88% of participants across all settings and by ≥ 95% at settings with physician-led care (metabolic clinic, emergency department, and hospital inpatient units) (Fig 1a–e). Appropriate treatment and provider knowledge were considered essential to reported satisfaction by ≥ 75% of participants at settings where care was physician led. Coordination of care with other providers was considered essential by > 60% of visitors to these settings, especially visitors to hospital inpatient units (82%). Attention to non-medical needs was considered essential by a minority of participants at all settings.

a Importance of factors contributing to caregiver satisfaction with metabolic clinic care. b Importance of factors contributing to caregiver satisfaction with emergency department care. c Importance of factors contributing to caregiver satisfaction with blood laboratory care. d Importance of factors contributing to caregiver satisfaction with hospital inpatient care. e Importance of factors contributing to caregiver satisfaction with pharmacy services. HCP healthcare practitioner

The only factors rated as essential to satisfaction with blood laboratory care by a majority of participants were care provider attitudes (68%) and communication with the child/caregiver (54%). At the pharmacy, more than 70% of participants identified factors related to the timely, correct acquirement of required products as essential to their satisfaction with care.

3.3 Memorable Experiences

A minority of participants reported a memorable positive or negative experience at any setting in the past year (Fig. 2). The proportion of participants with a memorable positive experience ranged from 10% (pharmacy) to 17% (hospital inpatient unit) of participants whose child visited the queried setting in the past year. Comparable proportions of participants had a memorable negative experience, with a range from 8% at the pharmacy to 22% during hospitalizations.

In narrative descriptions of memorable experiences, qualitative themes differed by setting (Table 4). Provider/staff demeanor was reported to contribute to positive/negative experiences at all settings except the emergency department. Good or poor communication with the family by providers/staff contributed to several memorable experiences at the metabolic clinic. At the emergency department, receipt of timely treatment or care and perceived coordination among providers/staff coordinating contributed to some positive experiences, whereas aspects of care contributing to negative experiences included providers/staff not following an emergency protocol letter supplied by the family and providers/staff lacking relevant skills or knowledge. Wait times for care or products contributed to memorable experiences at the blood laboratory and the pharmacy. Multiple blood draw attempts and errors in filling product orders contributed to several negative experiences at the blood laboratory and pharmacy, respectively.

3.4 Family-Centered Care

Participants reported that their child’s healthcare services at the metabolic clinic were family centered to a fairly great (score of 5) or great (score of 6) extent for all but one subscale of the MPOC-20 (Table 5). The median score for the “Providing General Information” subscale (capturing the extent to which providers shared information and resources about the IMD and available services) was 4.00. Participants who reported non-satisfaction with metabolic clinic care had statistically significantly lower median scores across all MPOC-20 subscales compared with those reporting satisfaction. Participants living in larger communities had a higher median score (p = 0.045) on the “Enabling and Partnership” subscale (capturing the extent to which participants felt they had the opportunity to participate in decision making) than those living in smaller communities. There were no significant differences associated with travel time for any MPOC-20 subscale.

3.5 Sensitivity Analyses

The proportion of participants who were satisfied with care at each setting among those whose children accessed care at four to five settings (proxy for higher healthcare needs) was comparable to the proportion for the total sample (ESM). From analyses of the IMD diagnoses of children who visited the emergency department and hospital inpatient units (ESM), we found that diagnoses among children with one visit to the emergency department were quite variable; those visiting three or more times most often had a diagnosis characterized by a risk of acute exacerbations. Children who were hospitalized at least once tended to have IMD diagnoses characterized by a risk of acute crises and/or complex multi-system manifestations. Among participants reporting memorable positive or negative experiences, although data were sparse, descriptively, a smaller proportion of participants reporting a negative memorable experience at a setting in the past year reported being satisfied with care at that setting (30–37%, setting dependent) relative to participants with positive memorable experiences (from ~63% to 97%, setting dependent).

3.6 Main Providers, Care Coordination, and Community Service Use

The majority of participants (n = 141, 57%) identified a metabolic clinic provider as their child’s main healthcare provider, 27% (n = 67) identified a family physician, and 12% (n = 30) identified a non-metabolic pediatrician. A minority reported that the main provider had provided them with a written visit summary for at least one visit in the past year (32%) or created a shared care plan for the child (11%); almost half (47%) did not know whether they had a shared care plan.

Approximately half of the participants (126/245, 51%) reported that their child used multiple types of health services in the past year, of whom 58% (n = 71) received support to coordinate those services (Table 6). Of caregivers receiving care coordination support, 78% (n =53) received support from someone associated with their child’s main provider. Fifty participants (20%) reported that they or their child needed or used community services for IMD care (Table 6), of whom 40% had problems accessing these services.

4 Discussion

Caregivers of children with IMD participating in this study were generally satisfied with the care their child received across a range of settings and factors considered essential to care and were quite similar across settings. Direct comparisons of satisfaction ratings across settings should be avoided; satisfaction may be influenced not only by the quality of care provided but also by other factors such as the urgency of care required, providers’ specialized knowledge of the child’s condition, and the degree of familiarity between the family and a setting’s care providers. However, some commonalities could be seen in our results. Provider communication with the family, a key principle of family-centered care, was considered essential to satisfaction with care by the vast majority of participants across all settings, as was provider attitudes. Appropriate treatment, provider knowledge, and coordination were considered essential by most participants visiting settings with physician-led care (metabolic clinic, hospitalizations, emergency department). These factors were echoed in the qualitative findings regarding memorable experiences. Among participants reporting a memorable negative experience in the past year, providers’ demeanor, lack of communication, lack of involvement of the family, or disregard of an emergency protocol letter were frequently mentioned factors contributing to those experiences at physician-led care settings. These findings are consistent with the literature on important contributors to the healthcare experiences of children with chronic conditions and their families [11,12,13,14].

Our post-hoc sensitivity analysis indicated that participants with memorable positive experiences at a setting were likely to be satisfied with care provision at that setting while those with negative experiences were likely to be non-satisfied. The numbers were small and data are cross-sectional; causality is difficult to assess. We speculate that a memorable experience may influence participants’ overall satisfaction ratings; if so, attention to the aspects of care related to memorable experiences could improve satisfaction. Family-centered care must, however, be tailored to specific settings [11]. The settings where the largest proportions of participants reported a negative experience were hospital inpatient units (22%) and the emergency department (19%). These settings are related: most of the participants (40/46) whose children were hospitalized at least once in the past year also had at least one visit to the emergency department (data not shown). Children who were hospitalized and/or who experienced three or more emergency department visits in the past year often had IMD diagnoses characterized by a risk of acute exacerbations. However, because of small numbers, we were not able to analyze associations between specific IMD and satisfaction ratings. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations for acute exacerbations can be very stressful for caregivers [29, 30]; we speculate that the stresses associated with the child’s need for acute care may influence their caregivers’ satisfaction with care but we were not able to directly evaluate this within our data. In our previous study of caregivers of children with IMD [17], some caregivers felt that emergency department providers were not adequately familiar with IMD-specific care and that care coordination during hospitalizations was poor. In this study, at the emergency department, several participants expressed dissatisfaction with providers/staff not following an emergency protocol letter. There was no single common aspect of care contributing to negative experiences during hospitalization. We recommend further research to identify predictors of care satisfaction, with an emphasis on factors contributing to poor experiences in the emergency department and during hospitalization.

Consistent with our previous qualitative study [17], caregiver participants considered metabolic clinic care to be strongly family centered, as evidenced by high scores in most of the MPOC-20 subscales. A common recommendation to address the needs of children with chronic conditions is the identification of a ‘medical home’. While the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a primary care provider as a medical home [31], for many children with IMD, the metabolic clinic provides the treatment and care most relevant to the health needs of the child and is thus a potential alternative. A medical home should have relational continuity, where the child and caregiver are familiar with the healthcare providers and feel that they are partners in their child’s care [31]. Our results highlight this as a strength of the metabolic clinic, which presents as a group of providers familiar to and trusted by caregivers. The metabolic clinic’s familiarity with patient needs may also make it well placed to address some of the issues at non-IMD-specific settings that caregivers identified as contributors to negative experiences, such as problems with receiving timely and correct products from the pharmacy.

The metabolic clinic, however, does not have all of the recommended features of a medical home. First, while caregivers perceived strong relationships with clinic providers, only approximately half of participants considered someone in the metabolic clinic to be their child’s main provider. Second, ideally, a medical home coordinates a child’s care, with active communication with other healthcare and support services [31, 32]. Participants did feel that ‘coordinated and comprehensive care’ was provided by the metabolic clinic to a great extent (5.75, interquartile range 2.00). Most clinics lack providers with a defined mandate to coordinate with other services or help families access community services. This may be reflected in participants’ ratings of the metabolic clinic’s provision of general information (4.00, interquartile range 3.10), indicating that care related to this subscale was provided to only a moderate extent. Similarly, few participants (20%) used or needed community services but nearly half (40%) of those users experienced trouble accessing such services. In addition, few caregivers had written visit summaries (32%) or shared care plans (11%) developed by the main providers. The creation of documentation that families can use to share information with a wider network of providers is an area where there is potential for the metabolic clinic to play a greater role. Importantly, of those receiving care coordination support from a provider, nearly all (94%) were satisfied with that support, suggesting that there may be effective existing practices that can be replicated.

A final consideration of the metabolic clinic’s suitability as a medical home is its accessibility. The metabolic clinic is a specialist health service, with only 16 pediatric centers across Canada, mostly hospital based [17]. This may present funding and geographic challenges to service provision [33]. While more than half of participants (53%) live in large cities, participants in smaller communities may be farther away from metabolic centers and in our exploratory analysis, we found that these participants may be less likely to be satisfied with metabolic care. This aligns with the literature suggesting that experiences with care may be different for residents of small communities [27, 34]. Forty-eight percent of participants lived more than 1 h from the metabolic clinic, adding time and potentially expenses (e.g., transportation, lost employment time) to the activity of seeking care. While we collected data prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, interventions that have been implemented to control the pandemic have included delivering more outpatient care via telehealth. Understanding how this virtual care impacts families’ experiences with respect to travel time, communication with providers, and other aspects of metabolic care is a priority for future research. We also recommend that further studies investigate the family centeredness of primary care and community pediatric clinics, which were identified as the main providers for a substantial minority of participants.

This study is the first that we know of to quantitatively survey caregivers of children across a broad range of IMD on their experiences with healthcare interactions. It builds on our previous qualitative work [17, 20] by quantifying satisfaction with care across a larger sample of families and identifying a number of potential contributors to care experiences that could be targeted for improvement. Questionnaires were sent to all parents of children in the original cohort study, providing a broad participant base across Canada and strengthening generalizability. We measured satisfaction with care at five healthcare settings common for children with IMD, enabling contextualization within each setting’s specific purpose and structure. This study has limitations. Caregivers of children with intense disease management or treatment requirements may be under-represented because of the time required to complete the questionnaire. Most respondents were female, with relatively high educational attainment and household income. This prevents us from understanding care experiences from diverse perspectives, including those of male caregivers and of families who may have fewer financial resources, and therefore limits the generalizability of our findings. This was a retrospective survey and may have been subject to recall bias. Health service use and experiences vary by disease and disease severity [35], as does the risk of acute exacerbations. Our sample size, however, was too small to compare experiences by IMD. Similarly, although healthcare is delivered differently in different provinces and regions, we were unable to explore geographic associations with care. In addition, this study examined perceptions of general experiences with care, not perceptions of individual care experiences, and the provision of narrative data about memorable experiences was qualitative and optional. We are therefore limited in our ability to draw conclusions about the specific aspects of care that contribute to adverse experiences.

5 Conclusions

While participating caregivers’ satisfaction with care for children with IMD was high, we identified important areas where care could be improved, including care coordination and issues related to poor experiences in the emergency department and during hospitalizations. To ensure that improvements are meaningful, we recommend further prospective research to better understand the frequency of adverse experiences and the common characteristics of those experiences. This information could be used to develop interventions to address identified gaps and improve care for children with IMD and their families, and to further explore a suitable medical home for children with IMD.

References

Waters D, Adeloye D, Woolham D, Wastnedge E, Patel S, Rudan I. Global birth prevalence and mortality from inborn errors of metabolism: a systematic analysis of the evidence. J Glob Health. 2018;8(2):021102.

Dewan T, Cohen E. Children with medical complexity in Canada. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18(10):518–22.

Hardy B-J, Séguin B, Goodsaid F, Jimenez-Sanchez G, Singer PA, Daar AS. The next steps for genomic medicine: challenges and opportunities for the developing world. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(S1):S23–7.

Cohen E, Berry JG, Camacho X, Anderson G, Wodchis W, Guttmann A. Patterns and costs of health care use of children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1463–70.

Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001570.

Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759–69.

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

NHS National Quality Board. NHS patient experience framework. 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215159/dh_132788.pdf. Accessed 5 Jul 2021.

Picker Institute Europe. Principles of person-centred care. 2021. https://www.picker.org/about-us/picker-principles-of-person-centred-care/. Accessed 5 Jul 2021.

Coulter A, Locock L, Ziebland S, Calabrese J. Collecting data on patient experience is not enough: they must be used to improve care. BMJ. 2014;348:g2225.

Council on Children with Disabilities and Medical Home Implementation Project Advisory Committee. Patient- and family-centered care coordination: a framework for integrating care for children and youth across multiple systems. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):e1451–60.

Stille C, Turchi RM, Antonelli R, Cabana MD, Cheng TL, Laraque D, et al. The family-centered medical home: specific considerations for child health research and policy. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(4):211–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2010.05.002.

Arauz Boudreau A, Goodman E, Kurowski D, Perrin JM, Cooley WC, Kuhlthau K. Care coordination and unmet specialty care among children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1046–53.

Hill C, Knafl KA, Santacroce SJ. Family-centered care from the perspective of parents of children cared for in a pediatric intensive care unit: an integrative review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;41:22–33.

Cederbaum JA, LeMons C, Rosen M, Ahrens M, Vonachen S, Cederbaum SD. Psychosocial issues and coping strategies in families affected by urea cycle disorders. J Pediatr. 2001;138(1):S72-80.

Potter BK, Khangura SD, Tingley K, Chakraborty P, Little J. Translating rare-disease therapies into improved care for patients and families: what are the right outcomes, designs, and engagement approaches in health-systems research? Genet Med. 2016;18(2):117–23.

Siddiq S, Wilson BJ, Graham ID, Lamoureux M, Khangura SD, Tingley K, et al. Experiences of caregivers of children with inherited metabolic diseases: a qualitative study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11(1):168.

Morrison T, Bösch F, Landolt MA, Kožich V, Huemer M, Morris AAM. Homocystinuria patient and caregiver survey: experiences of diagnosis and patient satisfaction. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):124.

Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method. New York: Wiley; 2007.

Khangura SD, Tingley K, Chakraborty P, Coyle D, Kronick JB, Laberge A-M, et al. Child and family experiences with inborn errors of metabolism: a qualitative interview study with representatives of patient groups. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2016;39(1):139–47.

Khangura SD, Karaceper MD, Trakadis Y, Mitchell JJ, Chakraborty P, Tingley K, et al. Scoping review of patient- and family-oriented outcomes and measures for chronic pediatric disease. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(1):7.

Groves RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, Lepkowski JM, Singer E, Tourangeau R. Survey methodology. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2009.

Gidengil C, Parast L, Burkhart Q, Brown J, Elliott MN, Lion KC, et al. Development and implementation of the family experiences with coordination of care survey quality measures. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(8):863–70.

King S, Rosenbaum P, King G. The Measure of Processes of Care (MPOC): a means to assess family-centered behaviours of health care providers. Hamilton (ON): McMaster University, Neurodevelopmental Clinical Research Unit; 1995.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Nathaniel G, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

Karunanayake C, Rennie D, Hagel L, Lawson J, Janzen B, Pickett W, et al. Access to specialist care in rural Saskatchewan: the Saskatchewan Rural Health Study. Healthcare. 2015;3(1):84–99.

Sibley LM, Weiner JP. An evaluation of access to health care services along the rural-urban continuum in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):20.

Garro A, Thurman SK, Kerwin ME, Ducette JP. Parent/caregiver stress during pediatric hospitalization for chronic feeding problems. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20(4):268–75.

Commodari E. Children staying in hospital: a research on psychological stress of caregivers. Ital J Pediatr. 2010;36(1):40.

Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1):184–6.

Lipkin PH, Alexander J, Cartwright JD, Desch LW, Duby JC, Edwards DR, et al. Care coordination in the medical home: integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1238–44.

Pordes E, Gordon J, Sanders LM, Lee M, Cohen E. Models of care delivery for children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2017;141(3):212–23.

Shah TI, Clark AF, Seabrook JA, Sibbald S, Gilliland JA. Geographic accessibility to primary care providers: comparing rural and urban areas in Southwestern Ontario. Can Geogr/Le Géographe Can. 2020;64(1):65–78.

Wang Y, Sango-Jordan M, Caggana M. Acute care utilization for inherited metabolic diseases among children identified through newborn screening in New York state. Genet Med. 2014;16(9):665–70.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Shabnaz Siddiq for contributions to scale development and study conceptualization; Sara Khangura for preliminary research; Alana Fairfax and Jessica Tao for survey mailout support and data entry; Monica Lamoureux and Kylie Tingley for general study support; and Zobaida Al-Baldawi and Zeinab Moazin for copy editing assistance. The authors also thank all investigators who belong to the Canadian Inherited Metabolic Diseases Research Network who participated in foundation work that led to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Emerging Grant: Rare Diseases (Emerging team in rare diseases: Achieving the ‘triple aim’ for inborn errors of metabolism), # TR3–119195. The open access fee is supported by funding from the Canadian Insitutes for Health Research.

Conflicts of interest/Competiing interests

Kumanan Wilson is the CEO of CANImmunize Inc. He is a paid member of the data safety board for the Medicago vaccine trial and a paid external advisor for the Auditor General report. In the past 3 years, Michal Inbar-Feigenberg has had the following relationships, none of which is connected directly to the material covered in this article: served on advisory boards for Audentes Therapeutics, Sanofi Genzyme, Shire/Takeda, and Horizon Therapeutics; received consulting fees from Shire/Takeda; performed contracted research for Shire/Takeda and Sanofi Genzyme; received research support from Shire/Takeda, Sanofi Genzyme, and Vtess Inc/Mallinckrodt; received speaker fees from Horizon Therapeutics (May 2019); and had travel expenses paid by Sanofi Genzyme and Shire/Takeda. John J. Mitchell has worked with pharmaceutical companies that market products for the treatment of inborn errors mentioned in this article. This relationship did not have any impact on the design or review of this paper. Andrea J. Chow, Michael Pugliese, Laure A. Tessier, Pranesh Chakraborty, Ryan Iverson, Doug Coyle, Jonathan B. Kronick, Robin Hayeems, Walla Al-Hertani, Shailly Jain-Ghai, Anne-Marie Laberge, Julian Little, Chitra Prasad, Komudi Siriwardena, Rebecca Sparkes, Kathy N. Speechley, Sylvia Stockler, Yannis Trakadis, Jagdeep S. Walia, Brenda J. Wilson, and Beth K. Potter have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (Reference 16/101X) and the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (Reference 20160608-01H), as well as the research ethics boards of all participating hospital centers.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was explained on the cover page of the questionnaire. Completion and return of the questionnaire constituted informed consent.

Consent for publication

The Research Ethics Board did not require us to obtain consent specifically for publication of the results but participants received information about the survey and were instructed that completion and return of the questionnaire constituted consent to participate in the study.

Availability of data and material

The study questionnaire is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

BKP, PC, DC, JBK, KW, RH, WA, MIF, SJG, AML, JL, JJM, CP, KS, RS, KNS, SS, YT, JSW, and BJW conceptualized, designed, and planned the study. MP, LAT, PC, JBK, RH, SJG, AML, JJM, CP, KS, RS, KNS, SS, YT, JSW, and BKP acquired the data. AJC, MP, RI, and BKP analyzed and interpreted the data. DC, JBK, KW, RH, WA, MIF, AML, JL, JJM, CP, and SS interpreted the data. AJC, MP, and BKP drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Online Resource 1.

Eligible inherited metabolic diseases for the Canadian Inherited Metabolic Diseases Research Network cohort study (PDF 118 kb)

Online Resource 2.

Counts of all codes applied to qualitative data (PDF 322 kb)

Online Resource 3.

Additional analyses (PDF 314 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chow, A.J., Pugliese, M., Tessier, L.A. et al. Family Experiences with Care for Children with Inherited Metabolic Diseases in Canada: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Patient 15, 171–185 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00538-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00538-8