Abstract

Background

Health checks can detect risk factors and initiate prevention of cardiovascular diseases but there is no consensus on how to communicate the results. The aim of this study was to investigate the preferences of the general population for communicating health check results.

Methods

A randomly selected sample of the Swedish population aged 40–70 years completed a discrete choice experiment survey that included questions on sociodemographics, lifestyle and health and 15 choice questions consisting of six attributes (written results, notification method, consultation time, waiting time, lifestyle recommendation and cost). Data were analyzed with a latent class analysis (LCA). Relative importance of the attributes and predicted uptake for several scenarios were estimated.

Results

In the analysis, 432 individuals were included (response rate 29.6%). A three-class LCA model best fit the data. Cost was the most important attribute in all classes. Preferences heterogeneity was found for the other attributes; in Class 1, receiving consultation time and the written results were important, respondents in Class 2 dominated on costs and respondents in Class 3 found consultation time, waiting time and lifestyle recommendations to be important. Health literate respondents were more likely to belong to Class 3. The predicted uptake rates ranged from 7 to 88% for different health checks with large differences across the classes.

Conclusion

Cost was most important when deciding whether to participate in a health check. Although cost was the most important factor, it is not sufficient to offer health checks free-of-charge if other requirements regarding how the test results are communicated are not in place; participants need to be able to understand their results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A discrete choice experiment (a choice-based survey) investigated preferences for communicating health check results to the public. |

Cost of the health check, consultation time with a medically trained person and inclusion of lifestyle recommendations were most important. |

Average predicted uptake rates for health checks ranged from 7 to 88%. Health literacy predicted differences in preferences for communicating health check results. |

1 Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are multifactorial and in many cases modifiable. Basic health checks, where biomarkers (such as blood pressure, cholesterol and glucose) are measured and lifestyle is assessed, can provide a good estimation of cardiovascular risk and help to detect the often symptom-free risk factors. The European Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice recommend assessing the total cardiovascular risk in healthy patients [1]. Health checks combined with health counselling have shown to positively impact cardiovascular mortality [2].

Participation rate reflects on the acceptability of the program and is crucial for a prevention program to be effective on a population level. An effective screening program should, according to WHO, have a participation rate of over 70% [3]. A screening program should also be accessible to the whole population [4]. In the EU, the participation rates of health checks have been relatively low. For instance, in Sweden, uptake was 65% or lower [5] and in the UK, 30.1% of the eligible population attended the NHS health checks, indicating a need for understanding of how the participation rates can be increased.

Lay people have expressed dissatisfaction with how test results are communicated to them and experienced difficulties understanding the test results [6, 7]. Not being able to utilize test results from health checks is a crucial obstacle for prevention. Other factors previously reported by individuals as important when receiving test results are availability and opening hours of the provider, waiting time, the format and framing of the written results (including an overall assessment), recommendations of what to do and where to find more information, consultation time, opportunity to ask questions, confidentiality, how the results are notified and costs [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

However, a formal quantitative assessment of the relative importance of these factors is lacking. This makes it difficult for policy makers to know what to prioritize when developing such national health check programs and to know how different factors will affect the uptake of health checks.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the preferences of the general population for communication of health check results. Furthermore, this study investigated preference heterogeneity and the predicted uptake of several health check implementation scenarios.

2 Methods

2.1 Discrete Choice Experiment

This study used a discrete choice experiment (DCE) to assess preferences of the general population. It is a method used to investigate individual preferences and can be used to determine the relative importance of different characteristics of an intervention and predict uptake of different interventions such as health checks [19, 20].

Respondents are presented with a series of choice tasks, each consisting of at least two alternatives that describe different options for the same intervention (e.g. health checks). Each alternative is described by several characteristics or attributes (e.g. consultation time for health checks) with varying levels (e.g. for consultation time: 0, 15 or 30 minutes). Respondents are asked to choose the alternative they prefer most within each choice task.

2.2 Attribute Selection and Experimental Design

The number of attributes that can be included in a DCE is limited. Therefore, attributes need to be carefully selected [21]. We identified a list of possible attributes based on previous research [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. This list was discussed with three experts (physicians and researchers) to ensure the attributes were consistent with current practice. The remaining attributes were discussed with eight individuals from the study population during three focus group interviews using the Nominal Group Technique [22]. This entailed participants discussing and ranking their five most important attributes. An additional 53 individuals from a convenience sample ranked all attributes from most to least important. Total and mean ranking scores were calculated for the attributes. Combining insights from previous research, expert feedback and ranking exercises, six attributes with accompanying levels were selected at a research group consolidation meeting (Table 1). Written results, waiting time, consultation time and lifestyle recommendations were top ranked while cost and notification method were chosen due to their policy relevancy. See Online Resource 1 in the electronic supplementary material (ESM), for more details about the attribute selection.

NGene 1.0 software was used to generate a Bayesian D-efficient design including best guess priors, which minimizes the sample size and the number of choice tasks every respondent is asked to complete based on optimizing the variance–covariance matrix. The design included an interaction between lifestyle recommendations and consultation time. Sixty unique choice tasks were generated. To limit the burden on respondents, the choice tasks were divided into four blocks of 15 unique choice tasks. Respondents were randomized to one of the blocks.

Each choice task consisted of two alternatives, so respondents were forced to choose between two health check alternatives. After that, respondents were asked if they would actually participate in the selected health check in real life or whether they preferred to opt-out (dual response design). An example of a choice task is presented in Fig. 1.

2.3 The Survey

The survey was web-based and constructed with the program Sawtooth Light House Studio 9.6.1 software. The first part of the survey included questions about sociodemographic factors; sex, age, education level, occupation, medical training, cohabitation and country of birth. The next part of the survey was the DCE. Before respondents were asked to complete the choice tasks, they received detailed information on the meaning of all attributes and levels as well as an example of how to complete a choice task. In addition, the context of the health check in the DCE was explained before the choice tasks; “Imagine being invited to a health check by the public health care authorities. The health check would take place at the local Primary Health Care Center. The testing would include analysis of glucose, blood lipids, blood pressure, as well as measurement of waist circumference, height and weight. You would also be asked to fill out a survey regarding your lifestyle habits. In the following DCE, imagine that no serious clinical findings were detected, but in any such case, you would be referred to health care immediately.”

The final part of the survey included additional questions about health status, risk perception, medical history and lifestyle (smoking, stress, physical activity and body mass index [BMI, kg/m2]). Understanding of test results is influenced by individuals’ health literacy, which relates to an individual’s ability to access, understand, appraise and apply health information and influences the use of health services [23]. Health literacy (HL) was measured using the validated Swedish Functional Health Literacy Scale [24].

To test for wording of the survey and to ensure that the respondents grasped the DCE, the survey was pilot tested with respondents from the target population (n = 32). Three think-aloud interviews were also conducted. The pilot resulted in minor changes in wording. Based on the pilot-test data, priors were updated to ensure the efficiency of the experimental design of the final DCE.

2.4 Study Population and Data Collection

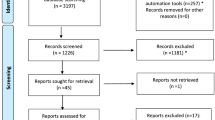

A letter was sent to a random sample of individuals (n = 1650) from the Swedish population aged 40–70 years inviting them to participate in the study. The letter included a link to a web survey together with information about the study. Consent to participate was obtained for all respondents. The respondents were informed that a paper survey could be sent to their home if they preferred. Two reminders were sent out after 3 and 6 weeks. Data was collected during January–March 2020. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (dnr:2019:03843). A flowchart of the study population is shown in Online Resource 2 (see ESM).

In Sweden, the 21 autonomous regions have responsibility for health care and decide on whether to offer subsidized general health checkups for their population. Among the regions that offer these, the design and the out-of-pocket costs for the health checkups differ. Most regions offer checkups for the general population from the age of 40 years. General health checkups include some level of testing (e.g., blood pressure and glucose) and is often followed up by a health counseling session with a trained nurse that focuses on lifestyle changes. The out-of-pocket cost for the citizens varies between 200 and 300 Swedish kroner (SEK) (free-of-charge in some regions). In addition to general health checkups, there are various private options available where the price is considerably higher. Most regions have implemented electronic health records.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

The analyses were performed using SPSS 25 and Nlogit 5. Descriptive statistics are presented with mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. All results were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Correlations between covariates were tested with χ2-test and Spearman’s correlation. The statistical analyses were restricted to subjects who completed a minimum of 13 out of 15 choice tasks (i.e. < 10% missing data on their choice tasks). Waiting time, consultation time and cost were tested for linearity by adding a linearly coded attribute in a conditional logit model as well as a dummy variable representing the highest level of the attribute. If the dummy was significant, the highest attribute level significantly deviated from the expected linear line and therefore was treated as a categorical variable. Non-linear attributes were effects coded [25]. Cost was treated as a linear attribute.

Based on the attribute levels presented in each choice task, respondents were assumed to choose the alternative that provides them with the highest utility. Therefore, data were analyzed with a panel latent class model. In addition, this model accounted for the multilevel structure of the data as each respondent answered 15 choice tasks. For this study, a latent class analysis was performed so we could investigate not only respondents’ preferences but also preference heterogeneity. The model estimates unobserved ‘latent’ preferences of the respondents by using the data to identify segments of the sample with similar choice patterns [26]. Several models were estimated including different numbers of classes (2–5). The models were compared based on model fit tests (Akaike information criteria [AIC] and log likelihood) and practical consideration (for instance, class membership of > 10%).

The final utility functions for alternative A, alternative B and the opt-out were

U describes the latent utility of participating in a health check. The systematic utility component (V) describes the measurable utility that respondent ‘r’ belonging to class ‘c’ reported for alternative ‘a’ in choice task ‘t’. β2−β11 represent the attribute level estimates that indicate the relative importance of each attribute (level). The sign of the estimate indicates whether the attribute level has a positive or a negative influence on the utility as compared to the reference level. The constant β1 in the utility function for alternative B was added to adjust for a left–right bias. β0 represents respondents’ preference for the opt-out over participating in a health check. The ε-term describes the unmeasured and unmeasurable variation in respondent’s preferences.

As part of the latent class model, a class assignment model was fitted and personal characteristics to predict class membership was used. In this study, we tested class membership predictions for age, educational level, HL, civil status, country of birth, economic constrains, lifestyle, medical history, risk perception, family history of myocardial infarction (MI) and self-perceived general health.

The relative importance of the attributes was calculated and compared across the different classes. In order to do so, the difference value for each attribute was calculated by subtracting the lowest estimate from the highest estimate within one attribute. The attribute with the largest difference value received an importance score of 1, representing the attribute that was deemed most important by respondents. The other difference values were divided by the largest difference value resulting in a relative distance between all other attributes and the most important attribute.

Predicted uptake was calculated for several hypothetical health check scenarios using \(\frac{1}{(1+{\mathrm{exp}}^{-V})}\), both for each latent class and as an average class-adjusted uptake (including all coefficients in the model). Based on existing health checks in Sweden, a ‘realistic scenario’ for the implementation of a national health check was formulated; cost 30 euro, 30 min consultation time, a letter besides accessing the results online, 2 weeks waiting time, written in everyday words, lifestyle recommendations included. Predicted uptake was then calculated for this realistic scenario as well as for several scenarios with a change in one of the attribute levels. By comparing the uptake rates of the different scenarios, the effect of changing one attribute at a time on the predicted uptake of the ‘realistic scenario’ was estimated. Based on the estimates of the latent class model, the least and most preferred health check scenarios were determined.

3 Results

In total, 482 respondents started the survey (response rate 29.6%). Seven respondents asked for a paper version of the survey. A total of 59 respondents were excluded from the analysis because they dropped out before the choice tasks (n = 36) or dropped out between choice tasks 1 and 10 (n = 23). These respondents included a higher proportion of younger individuals (p = 0.02) and individuals born outside of Sweden (p = 0.01) than respondents who completed the survey. The final analysis included 423 individuals.

The characteristics of the respondents are summarized in Table 2. Most respondents were working, living together with a partner, had a university education and were born in Sweden. A fourth of the respondents were obese and 30% were diagnosed with or treated for hypertension.

3.1 Preferences for Cardiovascular Risk Information

On average (class-adjusted results), respondents’ decision to take part in a health check was mostly driven by the cost of the health check, followed by consultation time, inclusion of lifestyle recommendations, details of written results, waiting time and notification method. However, differences in preferences were found.

The latent class analysis identified three classes. The average probability was 43% of belonging to Class 1 while this was 11% for Class 2 and 46% for Class 3 (Table 3).

Classes 1 and 3 had a negative coefficient on the opt-out alternative (meaning that they were positive to participation) while Class 2 was positive to opt-out (negative to participating). In all classes, cost was the most important attribute considered; with increasing costs, the willingness to participate in the health check significantly decreased. At the attribute level, all attributes except for waiting time contributed to utility in Class 1, while cost and notification method were the only attributes contributing to the utility of respondents in Class 2 and notification method was the only attribute not contributing to utility in Class 3 (Table 3). More specifically, respondents in Class 3 preferred 15 minutes and 30 minutes of consultation time over no consultation, written results consisting of numerical values, everyday words and an overall assessment over only numerical values and receiving lifestyle recommendations. Additionally, respondents in Classes 1 and 2 preferred receiving their test results by letter over only being able to access their results through their electronic health records. Class 3 preferred waiting 2 days over 2 weeks. Respondents in Classes 1 and 2 were less likely to have sufficient HL compared with respondents in Class 3. The relative importance of each attribute is presented in Fig. 2.

3.2 Predicted Uptake

On average, the predicted uptake ranged from 7 to 88% between least and most preferred scenarios (Table 4). Class 1 had the highest predicted uptake for all the calculated scenarios. The predicted uptake for the realistic scenario was 66% but when made free of charge the uptake increased to 75%.

The effect of changing one attribute at a time on the predicted uptake of the ‘realistic scenario’ was estimated (Fig. 3). Increasing the cost of the health examination and excluding the consultation and lifestyle recommendation, while keeping all other attributes constant, decreased the predicted uptake the most.

Effect on ‘realistic scenario’ with one attribute level change*. *Change in predicted uptake if the ‘realistic scenario’ (average predicted uptake 66%) changed in one attribute level (written result in numerical and everyday words, notification through electronic health record and letter, 2 weeks waiting time, lifestyle recommendations included, 30-min consultation time, 300 SEK out-of-pocket cost)

4 Discussion

This study revealed three different patterns of preferences for taking part in a health check and communication of test results. Cost was the most important factor for all respondents and, together with notification method, the only attribute of importance for a minority (11%) group of respondents (Class 2). The other respondents specifically preferred consultation time and more comprehensive written results (Class 1) or consultation time, shorter waiting time and lifestyle recommendations (Class 3). Class membership was predicted by health literacy (HL). Individuals with sufficient HL were more likely to belong to Class 3. The higher emphasis on longer consultation time and more comprehensive written results in Class 1 might be a sign of a need for more support from the health care provider to utilize the test results due to a lower HL level. Respondents with lower HL level (Classes 1 and 2) also valued receiving a letter alongside accessing their results online as important, while respondents with sufficient HL (Class 3) did not.

The predicted uptake rate ranged between 7 and 88% from the least preferred to the most preferred health check scenario. The predicted uptake for the realistic scenario was on average 66%, which is similar to the observed uptake of 65% in a Swedish health check program [5]. About 43% of the respondents (Class 1) were very positive to participation and showed high willingness regardless of the condition of the health check. A higher willingness to participate in health programs from people with lower health literacy has been reported in previous studies on vaccination [27]. This might be an indication of a lower capacity to consider the details of health information when making informed decisions, but could also indicate a greater confidence in health institutes offering these programs. These individuals might also perceive the health check as an opportunity to learn more about cardiovascular risk factors and health in general [6]. Tailoring the health check based on preferences will not have a major impact on the uptake rate for such individuals. However, since respondents in this class are more likely to have low HL, meeting their needs is crucial for the utilization of the test results. Another group of respondents (Class 3) was positive to participation but sensitive to the conditions of the health check and showed the greatest variation in predicted uptake depending on the design of the health check. This might be explained by the higher HL level of this class, as these respondents are expected to have better understood the information in the DCE.

To reach the participation rate of > 70% recommended for screening programs by WHO, the ‘realistic scenario’ included in this study will need to be adjusted; either the cost will need to be decreased, an overall assessment added or waiting time decreased (Fig. 2). Although cost was the most important factor, it is not sufficient to offer health checks free of charge if other requirements regarding how the test results are communicated are not in place (enough consultation time, lifestyle recommendations and comprehensive, easy-to-read written results). The predicted uptake rate for the group that mainly took cost into consideration and were consistently negative to participation reached a maximum of 20%, even in cases where the health check was free of charge. This indicates that there are other factors not considered in this study, explaining why this group is reluctant to participate. Previous studies have found age [28] and living alone [5] to be associated with non-participation. No such associations were found in this study. Low income has also been associated with non-participation [5]. In this study, being financially strained was associated with class membership. People with financial strains were more likely to belong to class 2 (results not shown). Due to the correlation between financial constraints and health literacy, these variables could not be included in the LCM simultaneously.

We suggest that policy makers adapt the communication of test results based on the needs of individuals with low health literacy. Guidelines on how to communicate risk and to improve health literacy recommend, for example, re-writing the test results at a lower reading level and removing medical terminology, providing the information in multiple languages but also strengthening the counselling skills of health professionals by adapting techniques such as teach back [29, 30]. Furthermore, it is recommended to ensure that test results are accompanied by information about what to do next and to offer consultation time that supports informed decisions [29]. Also, a well-planned design of how test results from health checks are communicated will not only meet the needs of the of low-HL individuals but can also be a way to increase their HL [31]. Finally, when deciding on the price for health checks, consider the consequences for people with financial difficulties since they have a higher cardiovascular risk and therefore are important to recruit to health checks.

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

A random sample was used in this study. However, the response rate was only 29.9%, which may make it problematic to generalize the results to the whole population since some groups in society might not have been reached by this study. Six individuals contacted us, declining participation due to language difficulties or because they found it too exhausting. Additionally, ten individuals were lacking internet access and asked for a paper version of the survey. It is possible that more individuals did not participate of this reason. However, we think that the results apply for the majority of the population but acknowledge the fact that the preferences of minority groups probably were not adequately captured by this study. We suggest that future research investigate the preferences of these groups and use adapted recruitment strategies for that specific aim. We did not assess the respondents’ prior experience with health checks, which may have contributed to explaining differences in preferences.

5 Conclusion

Cost was most important when deciding whether to participate in a health check. Although cost was the most important factor, it is not sufficient to offer health checks free of charge if other requirements regarding how the test results are communicated are not in place; participants need to be able to understand their results. To optimize the use of health check test results, especially for low health literate people, health checks could be accompanied by tailored written reports, consultations and lifestyle recommendations.

References

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts): developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(11):np1–np96. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487316653709.

Blomstedt Y, Norberg M, Stenlund H, Nyström L, Lönnberg G, Boman K, et al. Impact of a combined community and primary care prevention strategy on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a cohort analysis based on 1 million person-years of follow-up in Västerbotten County, Sweden, during 1990–2006. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009651. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009651.

WHO position paper on mammography screening. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Socialstyrelsen. Nationella screeningpreogram - modell för bedömning, införande och uppföljning: Socialstyrelsen. 2019.

Norberg M, Blomstedt Y, Lönnberg G, Nyström L, Stenlund H, Wall S, et al. Community participation and sustainability—evidence over 25 years in the Västerbotten Intervention Programme. Glob Health Action. 2012;5(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v5i0.19166.

Grauman A, Hansson M, James S, Veldwijk J, Hoglund A. Exploring research participants’ perceptions of cardiovascular risk information—room for improvement and empowerment. Patient Educ Couns. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.03.010.

Marcus EN, Drummond D, Dietz N. Urban women’s preferences for learning of their mammogram result: a qualitative study. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(1):156–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-011-0284-1.

Baldwin DM, Quintela J, Duclos C, Staton EW, Pace WD. Patient preferences for notification of normal laboratory test results: a report from the ASIPS Collaborative. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-6-11.

Harte E, MacLure C, Martin A, Saunders CL, Meads C, Walter FM, et al. Reasons why people do not attend NHS Health Checks: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(666):e28–35. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X693929.

Giardina TD, Baldwin J, Nystrom DT, Sittig DF, Singh H. Patient perceptions of receiving test results via online portals: a mixed-methods study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(4):440–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocx140.

Litchfield IJ, Bentham LM, Lilford RJ, McManus RJ, Greenfield SM. Patient perspectives on test result communication in primary care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(632):e133–40. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X683929.

Kelman A, Robinson CO, Cochin E, Ahluwalia NJ, Braverman J, Chiauzzi E, et al. Communicating laboratory test results for rheumatoid factor: what do patients and physicians want? Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2501–17. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S104396.

Herrmann A, Sanson-Fisher R, Hall A, Wall L, Zdenkowski N, Waller A. Support persons’ preferences for the type of consultation and the format of information provided when making a cancer treatment decision. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):456. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3552-x.

Elder NC, Barney K. “But what does it mean for me?” Primary care patients’ communication preferences for test results notification. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(4):168–76.

Dryden R, Williams B, McCowan C, Themessl-Huber M. What do we know about who does and does not attend general health checks? Findings from a narrative scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:723. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-723.

Cheong AT, Khoo EM, Tong SF, Liew SM. To check or not to check? A qualitative study on how the public decides on health checks for cardiovascular disease prevention. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159438. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159438.

Sommer I, Titscher V, Gartlehner G. Participants’ expectations and experiences with periodic health examinations in Austria—a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):823. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3640-6.

Riley R, Coghill N, Montgomery A, Feder G, Horwood J. Experiences of patients and healthcare professionals of NHS cardiovascular health checks: a qualitative study. J Public Health (Oxf). 2016;38(3):543–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdv121.

Bekker-Grob EW. Discrete choice experiments in health care: theory and applications. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam; 2009.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(8):661–77.

Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, Bate A, van Teijlingen ER, Russell EM, et al. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(5):1–186.

Hiligsmann M, van Durme C, Geusens P, Dellaert BG, Dirksen CD, van der Weijden T, et al. Nominal group technique to select attributes for discrete choice experiments: an example for drug treatment choice in osteoporosis. Patient Prefer Adher. 2013;7:133–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S38408.

Sorensen K, Broucke SV, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80.

Wångdahl JM, Mårtensson LI. Measuring health literacy—the Swedish Functional Health Literacy scale. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29(1):165–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12125.

Bech M, Gyrd-Hansen D. Effects coding in discrete choice experiments. Health Econ. 2005;14(10):1079–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.984.

Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied choice analysis. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015.

Veldwijk J, van der Heide I, Rademakers J, Schuit AJ, de Wit GA, Uiters E, et al. Preferences for vaccination: does health literacy make a difference? Med Decis Mak. 2015;35(8):948–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x15597225.

Robson J, Dostal I, Sheikh A, Eldridge S, Madurasinghe V, Griffiths C, et al. The NHS Health Check in England: an evaluation of the first 4 years. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e008840. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008840.

Fischhoff B, Brewer N, Downs J. Communicating risks and benefits: an evidence-based user's guide: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. 2011.

National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. In: Us Department of Health and Human Services OoDPaHP, editor. Washington DC. 2010.

Osborne RH, Elsworth GR, Whitfield K. The Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ): an outcomes and evaluation measure for patient education and self-management interventions for people with chronic conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(2):192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.002.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a grant from the Swedish Heart and Lung Association [Grant Number: 20150049].

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from the Swedish Heart and Lung Association [Grant Number: 20150049].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (dnr:2019:03843).

Consent

Informed consent to participate was obtained for all respondents participating in the study.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the data management protocol included in the ethical application, but may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. ÅG and JV conducted the experimental design, ÅG constructed the survey and conducted the data collection. ÅG, JV and BH planned the statistical analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ÅG and all authors commented and contributed intellectually to previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed on all the steps taken in the project.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grauman, Å., Hansson, M., James, S. et al. Communicating Test Results from a General Health Check: Preferences from a Discrete Choice Experiment Survey. Patient 14, 649–660 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00512-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00512-4