Abstract

Background

There is an increasing focus on measuring performance indicators of health care providers, but there is a lack of patient input into what defines ‘good care.’

Objective

The primary objective was to develop a conceptual model of ‘good health care’ from the patient’s perspective. Exploratory analyses were also conducted to investigate (1) differences in patient priorities based on demographic and clinical factors, and (2) differences between patients and health stakeholders (e.g., clinicians, researchers) with respect to patient health care priorities.

Method

These objectives were accomplished using group concept mapping. Following statement generation, PatientsLikeMe members, Baltimore community members recruited through a university-affiliated clinic, and stakeholders individually sorted the statements into meaningful categories and rated the statements with respect to importance. Qualitative and quantitative analyses generated a final conceptual model.

Results

One hundred and fifty-seven patients and 17 stakeholders provided input during statement generation. The 1779-statement pool was reduced to 79 statements for the structuring (sorting and rating) activities. In total, 221 patients and 16 stakeholders completed structuring activities through group concept mapping software. Results yielded a 10-cluster solution, and patient priorities were found to be relatively invariant across demographic/clinical groups. Results were also similar between patients and stakeholders.

Conclusions

This comprehensive qualitative and quantitative investigation is an important first step in developing patient-reported outcome performance measures that capture the aspects of health care that are most important and relevant for patients. Limitations and future directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This research represents the development of a patient-driven conceptual model of ‘good health care’ using group concept mapping. |

Findings revealed a 10-cluster model of ‘good health care.’ |

The relative importance of these 10 aspects of good health care were similar across various patient groups, as well as between patients and health stakeholders (e.g., physicians, researchers, etc.). |

1 Introduction

There is an increasing focus on health care quality measurement to improve care quality, enhance efficiency, and structure incentives for providers. The assessment, benchmarking, and reporting of results according to quantitative indicators of performance is becoming an influential driver of reimbursement [1]. However, our current ability to track these improvements in health outcomes and connect them to value is limited by an existing portfolio of measures that fail to reflect the priorities of patients [2].

One strategy in aligning patient priorities with care delivery is through the definition of patient-reported outcomes (PROs), development of these outcomes into validated measures, and then definition of specific outcomes that can measure provider performance [3]. Patient priorities should be integral to each phase of the PRO development process to establish construct validity of the instrument [3,4,5]. However, there is a lack of research exploring what aspects of care and clinician performance are most important to patients from the patient’s perspective. Creating and utilizing Patient-Reported Outcomes in Performance Measurement (PRO-PMs) without first addressing this issue is premature and may result in measures that are not meaningful to patients, or useful. As a result, it is unlikely that patients will understand or apply such information in making health care decisions [6].

1.1 Need for Conceptual Model

The development of PRO measures is typically based on the conceptual models advanced by researchers and clinicians, such as the Institute of Medicine quality measurement criteria [7]. Frequently developed for use in clinical research, they may not be appropriate for use in clinical care settings [8]. Measures developed with patient involvement may involve different content, such as health-related quality of life, functional status, symptom and symptom burden, and health behaviors [3, 7, 9]. There are also aspects of care delivery that impact patient outcomes that are not systematically measured, such as satisfaction with care, trust, psychological well-being, and utility of preferences [9].

To date, there have been numerous studies that purportedly define patients’ perspectives on quality care, but few studies have included patients at the agenda-setting stage of research in a direct, deliberative, and participatory capacity [10]. Unfortunately, these studies are characterized by an inconsistent involvement of patients throughout the research process and token patient participation (e.g., one or two patients on an advisory board) [10, 11]. A recent review of techniques used to engage patients in primary-care-practice transformation found significant limitations and little evidence to support traditional efforts such as interviews, surveys, focus groups, and advisory groups [12]. As a result, it is important to build upon these initial researcher- and clinician-driven efforts to develop a model of quality care with more meaningful patient participation.

To address the goals for broader patient involvement and concept development, group concept mapping (GCM) has been advanced as an inclusive and participatory methodology [13]. Concept mapping [14] has been used in the public health domain for decades to assist in developing hypotheses and theories, to build conceptual models, and to explore the context surrounding health-related outcomes (e.g., [15,16,17]). For example, concept mapping has been used to define patient and health care provider outcome priorities in Parkinson’s disease [18] as well as determining patient-centered care requirements [19]. Such efforts highlight the value of defining conceptual models based on patient–provider collaboration. There are no known studies applying this method to patient perception of care quality, but the technique has been used to define the elements of a quality management model for integrated care [20].

1.2 Objectives of Study

The primary objective of this study was to generate a conceptual model of good health care from the patient perspective. To achieve this objective, statement generation and GCM software, Concept System© (CSGlobal MAX; www.conceptsystems.com), were utilized to generate a conceptual model and quantify health care priorities. PatientsLikeMe (PLM), a patient-powered research platform that enables patients of all conditions to report and share their personal health data, partnered with its online communities, academic partners at the University of Maryland (UMD) PATIENTS (PATient-centered Involvement in Evaluating the effectiveNess of TreatmentS) program and health stakeholder groups to obtain the perspectives of a diverse sample. Through these GCM analyses, we were able to explore quantitative differences in health care priorities between groups. This research represented part of a larger Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) grant aimed at defining ways to include patient-centered outcomes in provider performance measurement.

2 Methods

Consistent with typical GCM procedures, study procedures included the following phases: (1) preparation, (2) statement generation, (3) structuring, (4) representation, and (5) interpretation. As GCM is a linear process, the preparation, statement generation, and structuring stages are presented in the Methods section of this manuscript, while the final results of the GCM analyses (representation and interpretation) are presented in the Results section. This research was approved by the New England Independent Review Board (NEIRB).

2.1 Phase I: Preparation

The main goal of this phase is to refine the study focus, define the focus prompts, and to identify relevant stakeholders [13].

2.1.1 Participants

During an early phase of the RWJF grant, interviews with 26 individuals representing various interests in health care, including patient advocates (n = 7), purchasers (n = 6), clinicians (n = 4), researchers (n = 4), measure developers (n = 3), and health IT (n = 2) were conducted. The purpose of the interviews was to evaluate gaps in existing performance measurement efforts in PROs. Results from these interviews highlighted the need for a patient-driven conceptual model of health care. Information from the interviews was also used to develop the focus prompts and GCM statements (see below).

2.1.2 Focus Prompt Development

Based on insights gleaned from the stakeholder interviews, three open-ended prompts were developed to present in survey format to generate statements about good health care. Specifically: (1) Please give us statements that describe ‘good health care’ (2) What does ‘good health care’ look like? and (3) Think about the health care that you have received. What aspects of your care have you liked? Complementary survey items (e.g., How do patients describe ‘good health care’?) were developed for health stakeholders. Three prompts were utilized to minimize the possibility that item wording would bias responses, and prompts were presented in different orders to participants to compensate for order effects.

2.2 Phase II: Statement Generation

Statements describing good health care were generated from (1) PLM members, (2) health stakeholders, and (3) literature review. This method of triangulation was employed to ensure that the statement bank comprehensively captured all aspects of good health care.

2.2.1 Participants

Patients were recruited through PLM, an online research network that allows patients to share personal health information through structured data collection. PLM currently has over 600,000 members, representing 2900 different medical conditions.

PLM members were eligible for participation if they were 18 years of age or older, reported a primary residence in the United States (US), and reported having one of the following six health conditions: heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and arthritis. It was anticipated that obtaining input from these diverse patient groups would increase the heterogeneity of responses and would facilitate generation of a comprehensive pool of statements that accurately reflect the construct of ‘good health care’.

Survey invitations were sent via electronic message to potentially eligible PLM members. The survey included questions pertaining to patient demographic/clinical characteristics (see Table 1), as well as the three open-ended good health care prompts. Members were not remunerated for participation.

After invites were sent, the research team continually reviewed survey responses to determine when saturation had been reached. PLM member statement generation was completed in five days in July 2016. Of the 994 PLM members who were invited to participate, 187 (18.8% response rate) responded to the survey and 157 provided usable data and were retained for further analyses. PLM members generated 1277 statements about good health care (Table 1).

Health stakeholders, identified through investigator and PLM contacts in health care institutions and companies through chain referral, were sent an email invitation to participate in the anonymous, voluntary survey. Health stakeholders were not reimbursed for their time.

Seventeen health stakeholders participated in statement generation. Of the participants, six represented patient groups, six were providers, one was a researcher, two represented purchaser groups, and two worked in measure development. These stakeholders generated 287 statements pertaining to good health care.

2.2.2 Literature Review

A literature review was conducted to identify previous studies that have evaluated patient health care priorities and to extract this content. Specifically, a search of the MEDLINE and PsychINFO databases of peer-reviewed articles since 2000 was conducted using combinations of the following keywords: ‘patient reported outcome,’ ‘performance measure,’ ‘quality of care,’ ‘quality of health care,’ and ‘health care quality indicators.’ Potentially relevant articles were reviewed by research staff and information pertaining to patient health care priorities or aspects of health care that are important to patients was extracted and compiled into a list of statements. References from relevant articles were also reviewed to increase comprehensiveness of the literature search. In total, 146 statements pertaining to good health care were generated from this literature review.

2.2.3 Secondary Review of Non-Patient Stakeholder Interviews

Statements describing good health care were extracted through secondary content analysis of health stakeholder interview transcripts that were conducted during the Preparation stage. From the 26 interviews, 69 statements pertaining to good health care were extracted.

2.2.4 Statement Pool Cleaning and Reduction

PLM member and health stakeholder responses to survey prompts were reviewed by the research team (authors of this study); compound responses where participants identified multiple aspects of good health care in the same response were separated for purposes of analysis.

To eliminate duplicate content and reduce the statement bank for GCM, statements were coded and grouped by content. The purpose of coding and grouping the statements was to more easily identify statements that were potentially duplicative. Two coders from the research team independently reviewed all statements and assigned each statement one or more keywords, iteratively developing a shared bank of keywords. Across the pool of statements, approximately 250 codes were iteratively and collaboratively generated by the raters. Raters achieved high levels (91%) of agreement. Disagreements were reviewed and discussed with a third researcher on the research team, who helped the team determine final codes.

Once final codes were assigned, statements were sorted by code to facilitate removal of duplicative content and to generate ‘prototype’ statements (i.e., the statement that most clearly reflected the primary content of that group of statements).

Whenever possible, language from the original statements was retained, although revisions were made in favor of clarity, grammar, and spelling. Additionally, six researchers provided qualitative and quantitative feedback using a grading system to facilitate reduction of the statement pool. Specifically, each statement was graded as A (very important for inclusion), B, or C (less important for inclusion) to efficiently identify the statements that were most important for inclusion in the final statement pool. The researchers had backgrounds in qualitative research, psychometrics, performance measurement, medicine, and health policy and included four PatientsLikeMe researchers and two consultants. This iterative and collaborative process resulted in a final pool of 79 statements.

2.3 Phase III: Structuring (Rating and Sorting)

CSGlobal MAX (©2017, Concept Systems, Inc.) software for GCM was utilized in the current study. The participant information, rating, and sorting modules in Concept Systems were utilized for the purposes of the current study.

2.3.1 Participants

Participants for Phase III include PLM members, Baltimore community members, and health stakeholders. Each group of participants is described separately below.

According to Trochim [14], meaningful results in concept mapping can be accomplished with as few as 10–20 participants per group. Therefore, waves of invitations (n = 500) were sent to PLM members who met the same inclusion criteria as the Statement Generation phase with the intention of obtaining complete data from around 120 participants (approximately 20 participants for each of the six disease groups). In total, 3266 members were invited and 193 PLM members provided complete rating and/or sorting data; 172 of these members completed the rating exercise and 123 completed the sorting. Following consent, PLM members were given access to the three GCM activities: (1) participant information, (2) rating, and (3) sorting. Patients were not reimbursed for their time. Demographic information from PLM participants who chose to provide it is presented in Table 2.

To diversify the Structuring sample and to ensure that patients who were not members of PLM or did not have access to a computer or the Internet were not excluded from this research, a collaboration was established with UMD’s PATIENTS program. The PATIENTS program, funded through the Agency for Health care Research and Quality (Grant # 5R24HS022135), is designed to empower patients to get involved in health care research. This program engages people from the surrounding Baltimore communities, especially underserved and minority populations. Community affiliates of the PATIENTS program who served as volunteers and community partners were recruited at community events and identified through other PATIENTS program staff. PATIENTS program staff were present during study administration to create de-identified accounts for participants and assist with data collection. Patients were reimbursed for their time with $25 gift cards. Patients were eligible to participate if they were 18 years of age or older and were currently residing in the US. From two rounds of recruitment and testing, 28 Baltimore community members provided usable data; 27 of these patients completed the rating and 27 completed the sorting activities. Demographic information for those participants who chose to provide it is presented in Table 2.

Health stakeholders in the field of performance measurement were invited to participate in structuring, including health stakeholder participants from previous phases. They were sent an email inviting them to participate with a link to the Concept Systems program to complete the sorting and rating activities, described above. Sixteen health stakeholders completed the rating and 15 completed the sorting exercises. The sample consisted of four members of purchaser groups (e.g., health insurance companies), five members of patient advocacy groups, three members of providers such as physicians, health psychologists, and researchers, and four measure developers.

2.3.2 Procedure

The final statements were randomized and put into the Concept Systems program for purposes of ratingFootnote 1 and sorting. During the rating activity, patientsFootnote 2 and providersFootnote 3 were asked to rate the 79 statements on a scale of 1 = Not Important to 5 = Extremely Important. The sorting exercise required participants to read the list of 79 statements and to sort them into meaningful groups. Participants were asked not to sort statements according to priority or value or into a ‘miscellaneous’ or ‘other’ pile of dissimilar statements. All participants were instructed to complete the rating exercise prior to sorting, as completing the rating exercise (which required participants to read and consider the content of all 79 statements) could facilitate completion of the sorting task. However, participants were able to complete the exercises in the reverse order if they preferred.

3 Results (Phase IV: Representation and Interpretation)

3.1 Determining the Optimal Cluster Solution

Sorting and rating data was analyzed using CSGlobal MAX. First, to determine if data from the three groups of participants could be combined into a single conceptual model, results for the health stakeholders, PLM members, and Baltimore community members were evaluated separately. Importantly, if results suggested that these three participant groups conceptualize good health care in different ways, it would be inappropriate to aggregate their data into a single concept map (i.e., the unique conceptual differences would be lost when results are averaged together, especially given the differences in sample size between the three groups). This approach, as emergent and agglomerative, is in keeping with GCM’s structural basis.

Point and cluster rating maps were generated for the three groups of participants. Multiple cluster solutions (e.g., 10-clusters, 9-clusters, etc.) were generated and reviewed by the GCM and content experts, taking into account the visual, theoretical, and empirical evidence to guide selection of the optimal solution. Results across each participant group were relatively similar, supporting the aggregation of stakeholder data to generate an ‘all participant’ conceptual model.

Next, the group of concept mapping and content experts generated a point map using all data. This map provides a visual depiction of the conceptual relationship between statements, whereby statements that are closer together were sorted together more frequently by participants. Stress for the point map, which can be thought of a goodness of fit statistic (whereby lower stress values reflect better fit), was 0.196. Although there are no guidelines for what constitutes acceptable levels of stress, maps with stress values between 0.10 and 0.35 are considered readily interpretable [21]. Therefore, this map was deemed interpretable and the GCM and content experts proceeded with generating cluster maps.

After carefully reviewing the various cluster rating maps, GCM consultants and researchers identified the 10-cluster solution as the optimal solution (Fig. 1). Each cluster in this map represents a different aspect of good health care. Cluster layers represent the average ratings of importance of the statements within each cluster, with more layers representing higher ratings of importance. Cluster names corresponding to each cluster number are presented in Table 3.

Cluster rating map of good health care generated from all participant data. The clusters in this map represent different, or orthogonal aspects of good health care. The layers of each cluster represent the average ratings of importance of the statements within each cluster, with more layers representing higher ratings of importance. This cluster rating map was generated using all participant data

The Cluster Bridging Map (Fig. 2) shows the average bridging value for each cluster. Bridging values, which range from 0 to 1, are a summary statistic of the cohesion of the content within the cluster. Lower bridging values suggest that the cluster does a good job of reflecting the content in that part of the map. Cluster bridging values are also listed in Table 3.

Cluster bridging map of good health care generated from all participant data. This map depicts the average bridging value for each of the statements in the cluster. Bridging values range from 0 to 1, with lower values suggesting greater coherence of the content within the cluster. Lower bridging values also suggest that the cluster does a good job of reflecting the content in that part of the map

3.2 Cluster Naming

Names for each cluster (Table 3) were determined by (1) reviewing the cluster names provided by participants whose sorting produced results similar to the final cluster content,Footnote 4 and (2) by reviewing statements within each cluster. The cluster with the highest ratings of importance was Active Patient Role. Care Accessibility and Cost and Office Management, producing average ratings of 4.25 and 4.12, respectively, were the least important to participants in this study. However, it is important to recognize that there was only a 0.5 difference in ratings of importance between the most highly rated and the lowest rated cluster. This finding suggests that the initial statement generation phase was successful in identifying aspects of health care that are very/extremely important to many different types of patients.

A summary of the content within each cluster is provided in Table 3 along with sample statements to illustrate content from each cluster. All statements are available upon request.

3.3 Exploratory Analyses: Subgroup Comparisons

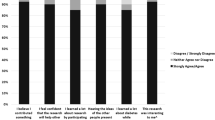

Pattern matching was utilized to evaluate differences in health care priorities between patient groups and between patients and health stakeholders. Essentially, pattern matching provides a visual depiction of the differences in ratings of importance of the clusters for different groups of participants. For example, the cluster ratings of patients who identified as having ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ health (n = 86) and the cluster ratings of patients who identified as having ‘good,’ ‘very good,’ or ‘excellent’ health (n = 113) are presented in Fig. 3. Cluster ratings of those with fair/poor health are on the left, while cluster ratings of patients who described their health as good/very good/excellent are on the right.

Absolute pattern match for patients with different health status’ (as reported by the patient). This pattern matching provides a visual depiction of the differences in ratings of importance of the clusters for two groups of participants, (1) patients who identified as having ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ health (n = 86) and (2) patients who identified as having ‘good,’ ‘very good,’ or ‘excellent’ health (n = 113). Cluster ratings of those with fair/poor health are on the left, while cluster ratings of patients who described their health as good/very good/excellent are on the right. The axis minimum and maximum, or vertical rulers, are identical, producing an ‘absolute’ pattern match

These two groups produced extremely similar results, with comparable ratings of importance and health care priorities between groups. The correlation (r = 0.96) between these findings supports the similarity of the groups’ results.

Absolute pattern matching was utilized to explore whether there were differences between patients with respect to various demographic and clinical characteristics, including race, gender, age, primary diagnosis, and satisfaction with health care. Results from each analysis revealed high correlations, suggesting extremely similar results across patient groups. That is, patient priorities with respect to health care can be considered largely invariant across patient groups.

Similarly, pattern matching suggested minimal differences between patients recruited online (PLM members; n = 172) and those patients recruited in person (Baltimore community members; n = 27) (see Fig. 4), as well as between patients (n = 199) and health stakeholders (n = 16) (r = 0.97); see Fig. 5.

Absolute pattern match for patients recruited online versus patients recruited in person. This pattern matching provides a visual depiction of the differences in ratings of importance of the clusters for two groups of participants, (1) patients recruited online (PatientsLikeMe [PLM] members; n = 172) and (2) patients recruited in person (Baltimore community members; n = 27). Cluster ratings of patient recruited online are on the left, while cluster ratings of patients recruited in person are on the right. The axis minimum and maximum, or vertical rulers, are identical, producing an ‘absolute’ pattern match

Absolute pattern match for patients versus health stakeholders. This pattern matching provides a visual depiction of the differences in ratings of importance of the clusters for patients (n = 199) and health stakeholders (n = 16). Cluster ratings of patients are on the left, while cluster ratings of health stakeholders are on the right. The axis minimum and maximum, or vertical rulers, are identical, producing an ‘absolute’ pattern match

4 Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to generate a conceptual model of how patients define and prioritize aspects of health care. By recruiting an extensive and diverse pool of participants, we were able to develop a robust conceptual model that efficiently integrated a variety of perspectives. Further, collaboration with the PATIENTS program may have increased representation of patients who are underserved and typically underrepresented in research, including minority patients. This primarily patient-driven conceptual model could inform the development of measures intrinsically tied to value.

Exploration of differences in patient priorities revealed high Pearson correlations between patient groups, suggesting that patient priorities are relatively invariant across demographic and clinical characteristics. The parallels across varied patient demographic/clinical profiles is important for purposes of measurement and for making direct comparisons across patient groups. Results also revealed a high correspondence between the way that patients and providers conceptualize good health care and prioritize aspects of good health care from the patient’s perspective. This may be due to the relatively broad nature of the good health care statements; that is, they were generally applicable to various types of health care providers and experiences of patients with various medical conditions, and were not treatment specific.

When looked at holistically, the current conceptual model shows the level of challenge in delivering quality health care due to an interdependence of interpersonal, evidence-based, and contextual factors. The failure of any of these components could impact the quality of care and may influence outcomes, stressing the need to integrate measures that will improve our ability to connect accountability and factors of high quality. However, it should be noted that there is inconclusive evidence for the effects of patient-centered care on health outcomes [22, 23].

The current study supports and extends previous research efforts to understand patients’ perspectives regarding health care quality. For example, previous survey research suggests that patients focus on ‘bedside manner’ more than care effectiveness or outcomes [24]. The current study probed more deeply into the multidimensional nature of the patient–provider relationship, which incorporates individualized care, shared decision-making, and good communication around the rationale for treatments offered. This more comprehensive approach needs to be captured in our methods to elicit patient overall satisfaction and perception of value. Indeed, the conceptual model generated from the current study suggests that patients expect to share their preferences with their providers, have discussions about what components of treatment are working or not working, and be solicited for their opinions. These types of individualized interactions counter the use of ‘cookbook’ approaches and require a more contextual understanding of a patient’s condition (e.g., social and environmental influences) [25].

Clinicians and researchers generally rely on methodologies with limited engagement potential when attempting to capture the ‘patient voice’. In terms of analysis, GCM has advantages over qualitative methods using word analysis and code analysis approaches [26] by retaining the context of participant perspectives and reflecting the judgement of participants rather than forced categorization or opening up thematic analysis to researcher bias [26]. In addition, the use of online concept mapping allowed a broader range of perspectives than use of focus groups or interviews and required much less data collection and analysis time than those approaches.

However, there are limitations that should be noted. GCM relies on self-report, so there was no means of validating patient experiences, and it was not possible to validate patient-reported diagnoses against medical record or provider report. Additionally, convenience samples were utilized in the current study, which may not be representative of patients in general. The sample primarily comprised PLM members; members of this online community may be more conscious, engaged in their health, comfortable with sharing health information [27], and literate with regard to health issues than the general population. Online participation and use of the GCM software requires computer literacy, physical dexterity, Internet access, and desktop use. Although efforts were made to recruit additional participants with UMD’s PATIENTS program to increase representativeness of the sample, we faced challenges obtaining usable data from this group, which may have been due to limited computer literacy. This cohort also completed the exercises with research staff available to assist them in person, while other cohorts relied on online support if necessary. Finally, the focus of this study was on the quality of care received from the provider. Broader extenuating circumstances that may affect care (e.g., roles of hospitals, insurance companies, pharmacies, pharmaceutical companies, etc.) were not factored into the conceptual structure.

Notes

Once statements are entered into the system, the presentation order cannot be changed to account for potential order effects.

Patient prompt: When you think about the health care that you would like to receive, how important are each of the following?

Provider prompt: How important to patients are each of the following aspects of health care?

These are produced automatically by the Concept Systems program.

References

Donabedian A. The seven pillars of quality. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:1115–8.

Hibbard J. Engaging consumers in quality issues. In: Expert voices. National Institute for Health Care Management. 2005. https://www.nihcm.org/pdf/ExpertV9.pdf. Accessed 22 June 2018.

National Quality Forum. Patient reported outcomes (PROs) in performance measurement. 2013;1–35. https://www.qualityforum.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=72537. Accessed 22 June 2018.

Basch E, Torda P, Adams K. Standards for patient-reported outcome-based performance measures. JAMA. 2013;310:139–40.

Reeve BB, Wyrwich KW, Wu AW, Velikova G, Terwee CB, Snyder CF, et al. ISOQOL recommends minimum standards for patient-reported outcome measures used in patient-centered outcomes and comparative effectiveness research. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1889–905.

Shaller D, Sofaer S, Findlay SD, Hibbard JH, Lansky D, Delbanco S. Consumers and quality-driven health care: a call to action. Health Aff. 2003;22:95–101.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001.

Weldring T, Smith SM. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Health Serv Insights. 2013;6:61–8. https://doi.org/10.4137/HSI.S11093.

Jayadevappa R, Chhatre S. Patient centered care—a conceptual model and review of the state of the art. Open Health Serv Policy J. 2011;4:15–25.

Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, Wang Z, Nabhan M, Shippee N, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-89.

Sharma AE, Willard-Grace R, Willis A, Zieve O, Dube K, Parker C, et al. “How can we talk about patient-centered care without patients at the table?” lessons learned from patient advisory councils. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:775–84. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2016.06.150380.

Sharma AE, Grumbach K. Engaging patients in primary care practice transformation: theory, evidence and practice. Fam Pract. 2017;34:262–7.

Kane M, Trochim WMK. Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2007.

Trochim WMK. Pattern matching, validity, and conceptualization in program evaluation. Eval Rev. 1985;9:575–604.

Anderson L, Gwaltney MK, Sundra DL, Brownson RC, Kane M, Cross AW, et al. Using concept mapping to develop a logic model for the Prevention Research Centers Program. Prev Chronic Dis Chronic Dis. 2006;3:1–9.

Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, Houle B, Benoit C, Katz N, et al. Development and validation of the current opioid misuse measure. Pain. 2007;130:144–56.

Burke JG, O’Campo P, Peak GL, Gielen A, McDonnell KA, Trochim W. An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research methodology. Qual Heal Res. 2005;15:1392–410.

Hammarlund CA, Nilsson MH, Idvall M, Rosas SR, Hagell P. Conceptualizing and prioritizing clinical trial outcomes from the perspectives of people with Parkinson’s disease versus health care professionals: a concept mapping study. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1687–700.

Ogden K, Barr J, Greenfield D. Determining requirements for patient centered care: A participatory concept mapping study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):780. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2741-y.

Minkman M, Ahaus K, Fabbricotti I, Nabitz U, Huisman R. A quality management model for integrated care: results of a Delphi and Concept Mapping study. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2009;21:66–75.

Rosas SR, Kane M. Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Eval Program Plann. 2012;35:236–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003.

Dwamena F, Holmes-Ronver M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centered approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2.

Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:351–79.

Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. National survey examines perceptions of health care provider quality. 2014. http://www.norc.org/NewsEventsPublications/PressReleases/Pages/national-survey-examines-perceptions-of-health-care-provider-quality.aspx. Accessed 22 June 2018.

Weiner SJ, Schwartz A, Sharma G, Binns-Cavey A, Ashley M, Kelly B, et al. Patient-centered decision making and health care outcomes: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:573–9.

Jackson KM, Trochim WMK. Concept mapping as an alternative approach for the analysis of open-ended survey responses. Organ Res Methods. 2002;5:307–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442802237114.

Wicks P, Massagli M, Frost J, Brownstein C, Okun S, Vaughan T, et al. Sharing health data for better outcomes on PatientsLikeMe. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e19.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Susan Mende, BSN, MPH, Senior Program Officer at The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for her support and input on this project. We would like to thank PatientsLikeMe staff members and consultants who supported project conceptualization and execution, including Benjamin Heywood, MBA, Lyn Paget, MPH, Ryan Black, Ph.D., Sally Okun, BSN, RN, MMHS, Emily McNaughton, MPH, Kristina Simacek, MA, and Hannah Saltzman, BA. We thank Helen Burstin, MD, MPH and David Cella, Ph.D. for their consultation on project design and refining the large statement pool generated in this project. C. Daniel Mullins, Ph.D., Lynnee Roane, MS, RN, CCRP, and Barbarajean Shaneman-Robinson, RN MS of the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Pharmaceutical Health Services Research (PHSR) Department, are acknowledged for their assistance in recruiting for the Baltimore sample. Mary Kane, M.S., President and Principal Consultant, and Scott R. Rosas, Ph.D., Senior Consultant, of Concept Systems Incorporated provided integral input into the interpretation of the concept mapping results. In particular, we would like to thank all of our study participants from the PatientsLikeMe online community, Baltimore community, and stakeholders from various organizations for contributing their data to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EC was responsible for this study’s conception. EC and SM were responsible for the study’s design. All authors were responsible for acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. EC and SM were responsible for drafting the manuscript, and all authors were responsible for revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was funded through a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant 73040, awarded to PatientsLikeMe, Inc. on November 2, 2015.

Conflict of interest

Stacey McCaffrey, Ph.D. is a consultant for PatientsLikeMe, Inc. Emil Chiauzzi, Ph.D., Michael Hoole, B.S. and Caroline Chan, B.A. are employees of and own stock options in PatientsLikeMe, Inc.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by New England IRB (NEIRB), A WIRB-Copernicus Group Company on July 14, 2016, and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study during group concept mapping. The NEIRB determined that consent was not necessary for the statement generation phase of this study as it was voluntary, anonymous, and no personally identifying information was being collected.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

McCaffrey, S.A., Chiauzzi, E., Chan, C. et al. Understanding ‘Good Health care’ from the Patient’s Perspective: Development of a Conceptual Model Using Group Concept Mapping. Patient 12, 83–95 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-018-0320-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-018-0320-x