Abstract

Objective

Acute intermittent porphyria is a rare metabolic disorder that affects heme synthesis. Patients with acute intermittent porphyria may experience acute debilitating neurovisceral attacks that require frequent hospitalizations and negatively impact quality of life. Although clinical aspects of acute intermittent porphyria attacks have been documented, the experience of patients is not well known, particularly for those more severely affected patients who experience frequent attacks. The aim of the present study was to qualitatively characterize the experience of patients with acute intermittent porphyria who have frequent attacks, as well as the impact of the disease on daily living.

Methods

Patients with acute intermittent porphyria who experience frequent attacks were recruited and took part in 2-h qualitative one-on-one interviews with a semi-structured guide. Interviews were anonymized, transcribed, and coded. The inductive coding approach targeted textual data related to acute intermittent porphyria attack symptoms, chronic symptoms, and the impact of the disease. Saturation analysis was conducted to assess whether the research elicited an adequate account of patients’ experiences.

Results

In total, 19 patients with acute intermittent porphyria were interviewed (mean age 40 years; 79% female). Eighteen patients (95%) experienced both attack and chronic symptoms. Patients described attacks as the onset of unmanageable symptoms that generally lasted 3–5 days requiring hospitalization and/or treatment. Pain, nausea, and vomiting were considered key attack symptoms; pain, nausea, fatigue, and aspects of neuropathy (e.g., tingling and numbness) were considered key chronic symptoms.

Conclusions

In this study population of acute intermittent porphyria with frequent attacks, most patients had symptoms during and between attacks. In these patients, acute intermittent porphyria appears to have acute exacerbations as well as chronic day-to-day manifestations, and is not just intermittent as its name implies. As a result, patients reported limitations in their ability to function across multiple domains of their lives on a regular basis and not just during acute attacks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) is a rare, often mis/underdiagnosed, inherited metabolic disease characterized by acute potentially life-threatening attacks and in some patients, chronic debilitating multi-systemic symptoms and manifestations that negatively impact patients’ daily functioning and quality of life. |

This qualitative research study undertook one-to-one interviews with 19 patients with AIP to characterize their symptoms and the impact of the disease burden on their daily lives. |

Patients with AIP having frequent attacks may have both attack and chronic disease symptoms, suggesting in some patients, AIP is not just an ‘intermittent’ disease but also has chronic symptoms, many of which are disabling. |

1 Introduction

Acute hepatic porphyrias (AHPs) are a family of rare metabolic disorders each caused by a deficiency in one of four enzymes responsible for heme synthesis in the liver. Patients may experience acute debilitating neurovisceral attacks that require frequent hospitalizations and negatively impact quality of life [1,2,3]. The four AHPs are acute intermittent porphyria (AIP), δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase deficiency porphyria, hereditary coproporphyria, and variegate porphyria [1, 2]. Factors such as cytochrome P450-inducing drugs, dieting, or hormonal changes can induce aminolevulinate synthase 1, the first and rate-limiting enzyme in the heme pathway. This can result in accumulation of the neurotoxic intermediates δ-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen upstream of the enzyme deficiencies. Patients present with signs and symptoms that are secondary to widespread dysfunction across the central, peripheral, and autonomic nervous system [3, 4].

AIP, the most common type of AHP (~ 80% of cases), results from a deficiency in hydroxymethylbilane synthase (porphobilinogen deaminase), the third enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway [Fig. 1 of the electronic supplementary material (ESM)] [1]. Patients with AIP experiencing attacks present with highly morbid and potentially life-threatening symptoms [1,2,3]. The most commonly reported debilitating symptoms are diffuse severe pain affecting the abdomen, back, or limbs; other common attack signs and symptoms include nausea and vomiting, constipation, hypertension, motor weakness, insomnia, or anxiety [1,2,3, 5]. Porphyria attacks typically last 5–7 days [6], although more severe or prolonged attacks can occur, potentially causing paralysis, respiratory failure, and death [7, 8]. AIP attacks can also lead to frequent hospitalizations [2], long-term use of opioids [2, 9], and high rates of unemployment [10].

Emerging clinical data indicate that some patients with AHP have chronic disease manifestations outside of the attack setting. Natural history studies conducted both in Sweden and the USA [with manifest AIP in 91 (55%) and 77 (85%) patients, respectively] determined that approximately 20% of patients experienced chronic symptoms [5, 11]. However, a recent multinational natural history study in an AHP population experiencing recurrent attacks, found 64% of patients experienced symptoms between attacks [12].

Currently, there are no approved pharmacotherapies for the prevention of attacks or treatment of chronic AIP symptoms. Treatment is focused on managing attacks, which typically require urgent medical attention in a healthcare setting, pain management, and intravenous hemin for attacks. In some patients, hemin is used off label to prevent recurring attacks; however, clinical evidence about the efficacy and safety of chronic prophylactic hemin use is insufficient [2, 13].

Although the clinical aspects of AIP attacks have been described in the literature [1,2,3, 5] and some studies have explored the impact of AIP using quality-of-life tools and other standard measures [10, 14,15,16], little qualitative work has been conducted directly with patients to understand the overall picture of the disease burden from their perspective. The aim of the present study was to qualitatively characterize the experience of patients with AIP who have frequent attacks, as well as the impact of the disease on daily living.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Procedures

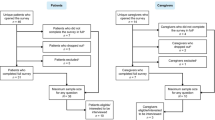

This was a qualitative research study in patients with AIP using a one-to-one interviewing approach via telephone with a semi-structured guide (Fig. 2 of the ESM). Concept elicitation interviews [17] were conducted to obtain information about the symptoms, impact, treatment experience, and preferences of patients with AIP. This manuscript reports patient symptom experience and impact. The research plan was developed with consideration of the recommendations and best scientific practices set forth in the US Food and Drug Administration Patient-Reported Outcome Guidance [18], the Roadmap to Patient-Focused Outcome Measurement in Clinical Trials [19], and best practices in qualitative research [20, 21]. The study was reviewed and approved by Quorum Review, an independent review board (Institutional Review Board Tracking No. 31332/1). The study methodology is summarized in Fig. 3 of the ESM.

2.2 Study Patients

Eligible patients were aged ≥ 18 years from the USA with a diagnosis of AIP that was made and/or confirmed by a porphyria specialist (this was reported by the patient; the study team did not have access to medical records), and were recruited in collaboration with the American Porphyria Foundation (APF) patient advocacy group. Recruiters from the APF identified and contacted potentially eligible patients listed in the APF database to participate in the study. Purposive sampling was implemented to select patients. If patients were willing to take part, and met the eligibility criteria, they were contacted by the interviewer (initially via e-mail) to answer any queries and for patients to provide informed consent. Patients were then contacted via the phone to discuss the study and schedule the interview. Patients were informed that researchers were interested in learning more about the experience of living with AIP. Patients were eligible if they: (1) had three or more porphyria attacks (defined as an acute episode of severe abdominal, back, and/or limb pain that may also have had associated symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, poor appetite, palpitations, and problems with mood or sleep) over the past 12 months, with at least one of the porphyria attacks requiring hemin treatment, and/or (2) were currently receiving hemin treatment on a scheduled basis for prevention of porphyria attacks. At least five patients currently receiving hemin treatment on a scheduled basis for prevention of porphyria attacks were targeted in the sample. Patients were excluded if they had any cognitive impairment that would prevent them from understanding and answering questions or if they did not speak English.

A total of 19 patients participated in the study, with an average age of 49 years and 79% were female (Table 1). The reported time to AIP diagnosis ranged from < 1 month to 23 years, and within the last 12 months, patients reported experiencing 0–20 attacks [mean 9.5 (standard deviation) 5.4].

2.3 Data Collection

Concepts representative of the patients’ experience were elicited during interviews conducted by trained interviewers experienced in patient-centered qualitative research. Interviews were conducted by Farrah Pompilus (research scientist), Sara Strzok (research manager), and JoAnne Liebeler (freelance interviewer). All interviewers were female and have completed National Institutes of Health Protecting Human Research Participants training. All interviewers were trained using a qualitative study playbook developed by Modus Outcomes (the company for which they worked), which provided a “how to” guide for qualitative research design, execution, analysis, and reporting to facilitate harmonization of processes across researchers. Before the interviews, all interviewers conferred to discuss the interviews, identify any potential issues with the interview guide, and ensure consistent interviewing practices. After a small set of interviews, the interviewers re-conferred to identify any discrepancies between them and notes were added to the interview guide to ensure alignment across the interviewers. Interviewers employed an open-ended line of questioning, limiting the potential for bias; however, questions reflected the specific research goals identified by the researchers prior to the interviews. Interviews were targeted to last approximately 2 h and repeated interviews were carried out. Field notes were made during the interviews on printed copies of the interview guide to help facilitate follow-up probes and document any non-verbal cues (e.g., changes in tone, sighs, and laughter). Interviews were audio-recorded, anonymized, and transcribed. Transcripts were not shared with participants and they did not provide feedback on the findings. The sample size for the concept elicitation interviews was based on the principle of saturation [22]. It was estimated that 20 patients would be necessary to reach saturation. Patients were compensated for participating in the interviews.

2.4 Data Analysis

Interviews were coded qualitatively by three data coders [Farrah Pompilus, Sara Strzok, and Caitlyn Gardner (junior research scientist)] using inductive coding [20] (ATLAS.ti software, Version 7). Coding was then reviewed by two different researchers and coding meetings were held to avoid bias and ensure consistency. Codes were developed by categorizing data clusters, creating a name for the concepts, and defining key concepts with clearly delineated boundaries and attributes. All concepts were created during analysis and pre-identified themes (attack symptoms, chronic symptoms, and impact of AIP) were used to help organize the concepts. Saturation analysis was conducted as follows: the transcripts were ordered chronologically based on the interview completion dates and grouped into quintiles. Codes used to characterize the raw data in the second quintile were compared with the codes used for the first quintile. This comparison was repeated for each additional quintile. Saturation was considered achieved when the cycle of data collection and analysis produced minimal or no new information, i.e., no new codes were necessary to describe the raw data [23].

3 Results

All recruited patients participated in the interviews. Saturation was achieved in terms of impact and attack symptoms, with the final quintile of interviews generating limited additional information. However, subsequent chronic symptom-focused re-analysis of the data indicated that saturation was achieved for chronic pain but not achieved in terms of non-pain chronic symptoms.

3.1 Overall Experience of Acute Intermittent Porphyria

When asked what it is like to have porphyria, patients reported a high burden of disease, experiences of both attack and chronic symptoms, and that AIP impacted a number of different areas of their lives. In total, patients reported 78 unique symptoms attributable to AIP attacks, 35 of which were also experienced chronically. Pain was usually the first symptom cited by patients when they were asked to define porphyria or to describe their symptom experience. Attack or chronic pain (not mutually exclusive) was reported as the most bothersome symptom by 13 patients (68%).

“I’ll feel like hot knives stabbing me.”

Nausea was reported as the next most bothersome by eight patients (42%).

“My nausea is uncontrollable. And I—my body just doesn’t feel right anymore.”

Other bothersome symptoms reported by two or more patients included abdominal pain specifically [n = 6 (32%)], memory loss [n = 4 (21%)], vomiting [n = 3 (16%)], constipation [n = 2 (11%)], and fatigue [n = 2 (11%)].

3.2 Attack Experience

Attacks were described as extreme incapacitating episodes characterized by progressive and uncontrollable symptoms with widespread dysfunction that preclude usual daily activities (Fig. 1a). Descriptions included:

“Completely unbearable.”

“Something that is beyond my control.”

“I’ll know from experience I need to be hospitalized.”

Attacks generally lasted 3–5 days, required treatment or hospitalization, and had a long recovery period.

“It will take me a couple of days just to lay in bed and sleep trying to recover.”

3.3 Attack Symptoms

The most common attack symptom, reported by all participants, was pain. Patients described attack pain as:

“Agonizing”

“Unbearable”

“Stabbing, knife-like”

“Burning, like a fire”

“I’m more than in tears, like I am literally like crying, crying, because the pain is just, it’s so bad, it’s like a stabbing, it’s a burning, it’s a pulling and a twisting, it’s everything you could imagine, it’s the absolute worst pain in the world.”

When asked to describe attack pain severity, patients characterized it as the worst imaginable level of pain, pain worse than the pain of childbirth or broken bones, or pain that is incompatible with life.

“Some days I just feel like I hurt so bad that it’s like I actually will think out loud, like how is porphyria compatible with life, you know? When you get to that point where you’re in that much pain, it’s not compatible with life. You can’t live like that.”

Patients explained that attack pain was “incapacitating,” rendering them unable to function in their work, social, or family roles, or to perform basic daily activities.

“I’ll be in so much pain that I won’t be able to move.”

Patients also explained that they knew they were experiencing an attack when they could no longer control pain at home and needed to seek help at a hospital or clinic, while others stated that attack pain is so severe that it cannot be controlled with pain medication.

“Just so uncontrollable, even with all my medications.”

Attack pain persisted until patients were successfully treated with medication, or until the end of the attack. Attack pain occurred in a variety of body locations, abdominal pain being the most frequent.

“It’s this spearing abdominal pain, like almost like someone is taking a hot butcher knife and tearing it through your stomach.”

Other locations included the entire body, stomach, back and spine, ribs, shoulders, arms, hands, legs, knees, feet, joints, and head. Further patient experiences describing attack pain are presented in Table 2.

The second most common attack symptom was nausea, reported by 16 patients (84%).

“The nausea is what just knocks me out. I mean it just—literally, I cannot do anything. I get up in the morning and if the nausea is that bad, I’ll start eating some toast, trying to at least eat something, because I can’t go without eating because that makes me sicker.”

The next most common attack symptom was vomiting, reported by 15 patients (79%).

“You’re like throwing up to the point where like you want to die, and you’re spitting up bile, and even though your stomach is completely empty and you’re like, ‘where is this coming from? I haven’t eaten in hours. I’ve been throwing up for half a day’. I’m vomiting foam at that point.”

Another common attack symptom was headache, reported by ten patients (53%).

“… headaches so bad that they’ve caused me to lose my sight on numerous occasions.”

The Table in the ESM lists other common attack symptoms reported by seven or more patients, along with descriptions and patient experiences. The symptoms experienced during an attack were described as extending beyond the period of the attack, leaving residual chronic symptoms and included two patients whose attack resulted in a coma.

3.4 Chronic Experience

Patients described the chronic experience of AIP as:

“Something I’m constantly having to manage.”

“Almost daily.”

“I don’t get a whole lot of relief in between attacks.”

Eighteen patients (95%) experienced chronic symptoms (defined as symptoms attributed to AIP experienced between attacks) with the remaining patient only experiencing symptoms during attacks. All the symptoms reported chronically were also reported during an attack, although chronic symptoms were described as less severe. The chronic symptom frequency ranged from occasional experiences with pain, fatigue, or nausea, to daily experiences of a wide range of symptoms (Fig. 1b). Patients also highlighted that the disease is not ‘intermittent’ as the name implies.

“My condition seems to be more chronic than it is intermittent.”

“There’s not a week that goes by that I don’t have [chronic symptoms].”

3.5 Chronic Symptoms

Chronic pain experienced between attacks was often characterized as sore, dull, aching, throbbing, and/or burning (Table 2) and was the most frequently reported chronic symptom, experienced by 17 patients (78%). Chronic pain was rarely described in the more extreme terms used to characterize attack pain and was not considered as severe.

“When I’m not having an attack I will experience some pain, like some joint pain in my knees and also the neuropathy in my hands. Those are my symptoms that don’t go away.”

However, some patients characterized more severe peak episodes of pain outside of an attack as sharp or stabbing.

“… pain level is probably like at a six out of 10, um, on a daily basis … I would say it feels like you—like I said, you have like little people in there with barbed wires, just like fighting.”

Many rated living with pain in the range of 2–6 out of 10 as a “good day” or “typical day” with porphyria, noting that their perception of pain is different from those who have never dealt with the degree of pain experienced by those with AIP.

“I have pain disassociation so that my level of pain is at a five all the time, which is probably someone else, a normal person’s 10, because I’m so used to the pain.”

Patients reported that chronic pain ranged from manageable with little impact, to having a significant impact on day-to-day activities.

“I don’t really sleep well at night at all from the porphyria because, um, my back hurts and, uh, my feet hurt and my legs, they hurt a lot.”

Twelve patients (63%) reported taking pain medications between attacks. Patients who experienced pain outside of their attacks reported variable frequency and duration of this pain. Some reported that pain was “constant” unless alleviated by medication, while others described pain as a sensation that comes and goes. Chronic pain was reported in a variety of body locations including the entire body, the abdomen, stomach, back (particularly lower back), buttocks, ribs, shoulders, arms, hands, legs, knees, feet, joints, and head. Patients also reported non-specific nerve and bone pain that they associated with AIP.

The second most common chronic symptom, reported by nine patients (47%), was neuropathy. The term was spontaneously generated by patients, and includes tingling, numbness, or loss of sensation.

“Nerve pain and nerve sensations because when you get numbness sometimes there’s nerves that are kind of alive and other parts that are dead. And it feels like something is crawling on you. And it’s like a bug is on your arm or something touches you on the middle of the night. It wakes you up. I get woken up a lot because of nerve sensation.”

The next most common chronic symptom was nausea, reported by seven patients (37%).

“I was nauseated every day and it was like a six to a seven on the scale.”

Other commonly reported chronic symptoms included insomnia by six patients (32%).

“There is a days [sic] I somehow I cannot sleep at all, no matter how, no matter how I am tired.”

Five patients (26%) reported fatigue.

“… it’s so frustrating. You know, you shouldn’t be that tired. You know, you should be able to live a normal life.”

3.6 Impact of Acute Intermittent Porphyria on Patients’ Lives

Patients reported AIP as having an impact on a number of different areas of their lives (Table 3). The most frequently reported impact was on sleep [n = 18 (95%)], ability to work [n = 16 (84%)], finances [n = 14 (74%); medical costs or inability to work], difficulty walking [n = 14 (74%)], and decreased socialization [n = 12 (63%)]. Patients frequently reported an impact on sleep from both chronic and attack symptoms.

“I don’t really sleep well at night at all from the porphyria because my back hurts and my feet hurt and my legs, they hurt a lot.”

The unpredictable nature of attacks and symptoms was also noted; patients reported never knowing how they will feel from day to day or when an incapacitating attack will occur, which impedes attendance at work and social activities.

“It’s completely unpredictable. There’s no way I could be a reliable employee to somebody because I could not guarantee that I will be there tomorrow for work.”

Patients highlighted the medical costs of the disease.

“As a matter of fact, I have to make a phone call to my secondary insurance provider finding out why they dropped me because I just received a $650,000 bill.”

The wide-ranging psychological impacts included challenging diagnostic journeys, lack of knowledge of the disease, not being believed by healthcare professionals, and being labeled as drug seeking.

“Very few doctors understand what porphyria is or even how to treat it.”

“I have to take all these stupid medications, and there’s so much stigma in society about prescription pain meds.”

4 Discussion

This qualitative study adds to the understanding of the patient experience of living with AIP that is characterized by frequent attacks, describing the wide array of patient-reported symptoms and the impact of the disease on patients’ ability to function. Pain was usually the first symptom cited by patients with AIP when asked to define porphyria or describe their experience of the disease. It was the most common and distressing symptom experienced by patients, both during attacks and chronically. Attacks were described as extreme events characterized by progressive and uncontrollable symptoms that preclude usual daily activities. Other attack symptoms included nausea, vomiting, headache, memory loss, constipation, weakness, paralysis, and numbness. Attacks generally lasted 3–5 days, but the recovery period was long and attack symptoms were described as extending into residual chronic symptoms. All but one patient reported chronic symptoms, describing AIP as something they are constantly having to manage, with some experiencing daily or almost daily symptoms. Pain was the most common symptom, experienced by 17 patients (89%), although it was rarely described in the more extreme terms used to characterize attack pain. This qualitative research indicates that in this group of patients with AIP who experience frequent attacks, most also face chronic disease manifestations and that the disease may not be ‘intermittent’ in character as its name suggests.

The findings regarding chronic symptoms are consistent with those reported in the EXPLORE natural history study (NCT02240784), where 65% of 112 patients with AHP with recurrent attacks (104 with AIP) reported experiencing chronic symptoms [12], with 46% of patients having these symptoms on a daily basis (most commonly pain, nausea, tiredness, and anxiety) [12]. In addition, a high burden of disease and acute and chronic disease manifestations were reported by patients with AHP and their care givers at a patient-focused drug development meeting that was recently held by the APF and the US Food and Drug Administration [24]. Lower rates (20 and 18%) of chronic symptoms were observed in two larger studies (n = 356 and n = 108) of patients with AHP; however, these studies included patients with less frequent attacks and patients with no manifest symptoms of AIP [5, 24, 25].

In assessing the impact of AIP on patients’ lives, aspects such as symptoms, unpredictability of knowing when the next attack would come, and treatment factors were shown to affect work/education, social relationships and roles, leisure and exercise, diet and nutrition, healthcare and treatment, free time, ability to travel, and emotional state. Consistent with findings in an earlier study [9], patients reported that they were unable to engage in employment at all or as fully as they would like, with 63% being unemployed. This, along with healthcare costs, influenced patients’ finances. Overall, these data support earlier studies that found the disease had a significant impact on patients’ quality of life [10, 15, 16].

This study has some limitations, including that biochemical data were not used to confirm porphyria attacks and that clinical diagnosis, although made by a porphyria specialist, was self-reported. Some selection bias is inherent in recruiting patients through a patient organization such as APF as patients may be more likely to join if they have worse disease; however, the aim of the study was to obtain a breadth of patients’ views rather than to assess the frequency of these symptoms. As all symptoms were self-reported, it is not possible to conclude that they were the result of AIP, particularly non-pain and chronic symptoms. Research suggests patients find attribution of the causes of symptoms difficult and can be inconsistent in their reporting [26]. The design of the study therefore means such conclusions are not possible; however, patients clearly had non-pain and chronic experiences and they felt these were attributable to AIP and were consistent with the understanding of AIP symptoms.

Furthermore, the etiology of chronic symptoms in this sample and in patients with AIP is not entirely clear. It is not well understood whether symptoms such as chronic pain or fatigue are caused by irreversible nerve damage or by ongoing nerve injury from the increased levels of porphyrin precursors (i.e., δ-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen). Additionally, non-pain chronic symptom concepts were continuing to emerge in the final quintile of interviews, which was not the case for attack symptoms. While the concept of saturation and at what point it is possible to conclude that no new insights will occur are sources of debate among researchers [27], we cannot conclude that saturation of non-pain chronic symptom concepts was achieved. Taken together, these data suggest that we are only beginning to understand the range of chronic and non-specific symptoms that some people with severe AIP experience, in addition to disabling attacks, and the frequency of their occurrence across a range of disease severities. Further research is warranted to better understand the full range of disease manifestations that patients with severe AIP experience.

5 Conclusion

The aim of the present study was to qualitatively characterize the experience of patients with AIP who experience frequent attacks, as well as the impact of the disease on daily living. The findings indicate that in the study population, the disease is not just ‘intermittent’ as its name implies, but has chronic manifestations that impact on patients’ lives and their ability to function. A wide variety of attack and chronic symptoms were reported that were similar among patients, with pain being the most frequent symptom both during attacks and chronically. This qualitative study suggests that in some patients with AIP who experience frequent attacks, the disease has acute exacerbations as well as chronic manifestations, which pervade patients’ lives on a frequent or even daily basis.

References

Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375(9718):924–37.

Anderson KE, Bloomer JR, Bonkovsky HL, Kushner JP, Pierach CA, Pimstone NR, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of the acute porphyrias. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(6):439–50.

Balwani M, Desnick RJ. The porphyrias: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2012;120(23):4496–504.

Pischik E, Kauppinen R. An update of clinical management of acute intermittent porphyria. Appl Clin Genet. 2015;8:201–14.

Bonkovsky HL, Maddukuri VC, Yazici C, Anderson KE, Bissell DM, Bloomer JR, et al. Acute porphyrias in the USA: features of 108 subjects from porphyrias consortium. Am J Med. 2014;127(12):1233–41.

Stein P, Badminton M, Barth J, Rees D, Stewart MF, et al. Best practice guidelines on clinical management of acute attacks of porphyria and their complications. Ann Clin Biochem. 2013;50(Pt 3):217–23.

Jeans JB, Savik K, Gross CR, Weimer MK, Bossenmaier IC, Pierach CA, et al. Mortality in patients with acute intermittent porphyria requiring hospitalization: a United States case series. Am J Med Genet. 1996;65(4):269–73.

Elder G, Harper P, Badminton M, Sandberg S, Deybach JC. The incidence of inherited porphyrias in Europe. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(5):849–57.

Naik H, Stoecker M, Sanderson SC, Balwani M, Desnick RJ. Experiences and concerns of patients with recurrent attacks of acute hepatic porphyria: a qualitative study. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;119(3):278–83.

Millward LM, Kelly P, Deacon A, Senior V, Peters TJ. Self-rated psychosocial consequences and quality of life in the acute porphyrias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2001;24(7):733–47.

Andersson C, Innala E, Backstrom T. Acute intermittent porphyria in women: clinical expression, use and experience of exogenous sex hormones: a population-based study in northern Sweden. J Intern Med. 2003;254(2):176–83.

Gouya L. EXPLORE: a prospective, multinational natural history study of acute hepatic porphyria patients with recurrent attacks. International Liver Congress, Paris, 11–15 Apr 2018.

Marsden JT, Guppy S, Stein P, Cox TM, Badminton M, Gardiner T, et al. Audit of the use of regular haem arginate infusions in patients with acute porphyria to prevent recurrent symptoms. JIMD Rep. 2015;22:57–65.

Millward LM, Kelly P, King A, Peters TJ. Anxiety and depression in the acute porphyrias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(6):1099–107.

Jimenez-Monreal AM, Murcia MA, Gomez-Murcia V, Bibiloni Mdel M, Pons A, Tur JA, et al. Anthropometric and quality-of-life parameters in acute intermittent porphyria patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(30):e1023.

Wikberg A, Jansson L, Lithner F. Women’s experience of suffering repeated severe attacks of acute intermittent porphyria. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(6):1348–55.

Britten N. Qualitative interviews in medical research. BMJ. 1995;311(6999):251–3.

US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labelling claims. 2009. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm193282.pdf. Accessed 7 Jun 2018.

US Food and Drug Administration. Roadmap to patient-focused outcome measurement in clinical trials. 2013. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DrugDevelopmentToolsQualificationProgram/ucm370177.htm. Accessed 7 Jun 2018.

Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–46.

Bryman A, Burgess B. Analyzing qualitative data. New York: Routledge; 2002.

Mason M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qual Soc Sci Res. 2010. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.3.1428

Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(9):1263–78.

American Porphyria Foundation. The voice of the patient: patient-focused drug development meeting. Acute porphyrias. 2017. http://www.porphyriafoundation.com/sites/default/files/APFPFDDMeetingMarch1%2C2017-TheVoiceofthePatient%20%281%29.pdf. Accessed 7 Jun 2018.

Bylesjo I, Wikberg A, Andersson C. Clinical aspects of acute intermittent porphyria in northern Sweden: a population-based study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2009;69(5):612–8.

Hyland ME, Lanario JW, Pooler J, Masoli M, Jones RC. How patient participation was used to develop a questionnaire that is fit for purpose for assessing quality of life in severe asthma. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:24.

Carlsen B, Glenton C. What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-26.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study. The first draft of the manuscript was written by the authors; editorial support for the preparation of the manuscript was provided by Adelphi Communications and funded by Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS, WQ, AW, CP, and SA contributed to the study design, data interpretation, manuscript development, and review of this article. JBK contributed to the data interpretation, manuscript development, and review of this article. FP, SS, and PM contributed to the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript development, and review of this article. DLH and JRH contributed to the study design, data collection, manuscript development, and review of this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA, USA. Data collection and analysis were performed by Modus Outcomes under the direction of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

Amy Simon, William Querbes, Alex Wei, Craig Penz, Jae B. Kim, and Sonalee Agarwal are employees of Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored this study. Farrah Pompilus, Sara Strzok, and Patrick Marquis are employees of Modus Outcomes and received funding from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals to conduct the study. Desiree Lyon Howe and Jessica R. Hungate are employees of the American Porphyria Foundation.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study may be available on request from the corresponding author (AS), based on the specific request. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise research participant privacy/consent.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Simon, A., Pompilus, F., Querbes, W. et al. Patient Perspective on Acute Intermittent Porphyria with Frequent Attacks: A Disease with Intermittent and Chronic Manifestations. Patient 11, 527–537 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-018-0319-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-018-0319-3