Abstract

Background

Adenomyosis is a poorly understood, benign disease of the uterus.

Objective

In this study, patient interviews were conducted to characterize the symptoms and impact of adenomyosis.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study in which women with adenomyosis were recruited from five US clinics and a health-related social network forum. Participants (aged 18–55 years) were pre-menopausal with a history of regular menstrual cycles. Participants were interviewed about their experiences with adenomyosis, symptoms and impacts on day-to-day activities (concept elicitation), and subsequently about the occurrence, relative severity, and impact of symptoms (card-sorting exercise).

Results

In total, 31 women were interviewed. Mean duration since onset of first adenomyosis symptom was 5.7 years; 41.9% reported severe/very severe adenomyosis. Over 50 symptoms and 30 impacts of adenomyosis were reported in the concept elicitation; 87% of symptoms were reported after 7 interviews and 78% of impacts after 5 interviews, indicating a condition with a significant symptom burden and a consistent presentation. The most common symptoms were heavy menstrual bleeding (87%), cramps (84%), and blood clots during menstrual bleeding (84%). The most common impacts were burdensome self-care hygiene (71%), and fatigue/low energy (71%). In the card-sorting exercise, the most commonly endorsed symptoms were pain during menstruation/menstrual cramps and heavy menstrual bleeding (both frequently rated as severe). The symptom with the highest impact was heavy menstrual bleeding.

Conclusion

Initiatives to understand women’s experiences with adenomyosis may improve management of the condition. This study provides a first step in understanding their experience and new information on the symptom profile of adenomyosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Limited information is available from the patient perspective regarding the signs, symptoms, and impacts of adenomyosis. A better understanding is required to improve the management of the condition. |

Interviews with women with adenomyosis found that the most common symptoms were heavy menstrual bleeding, cramps, and blood clots during menstrual bleeding. The most commonly reported impacts of adenomyosis were burdensome self-care hygiene, fatigue/low energy, and impacts on leisure/social activities, household/activities of daily living, travel, and physical activities. |

For both symptoms and impacts, saturation (the interview at which no novel concepts were gathered) was reached after a small number of interviews, indicating a condition with a consistent presentation. |

1 Introduction

Adenomyosis is an under-diagnosed disease of the uterus characterized by the abnormal presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium. This results in an enlarged uterus that microscopically exhibits ectopic, non-neoplastic endometrial glands and stroma surrounded by the hypertrophic and hyperplastic myometrium [1, 2]. Although the condition was first defined nearly 50 years ago, it remains both under-diagnosed and poorly understood due to the lack of a consensus definition, diagnostic difficulties, and inadequately defined symptoms [3]. The results of epidemiologic studies of adenomyosis are difficult to interpret due to the difficulties with diagnosis. Until relatively recently, diagnosis of adenomyosis was only possible on histologic examination of a uterus following a hysterectomy [4], and it has been reported to occur in 20–30% of women undergoing hysterectomy [5]. The symptoms of adenomyosis can include heavy menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhea, abnormal uterine bleeding, bloating, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, infertility, and miscarriage [3, 6].

No drugs have been approved by the US FDA for the treatment of adenomyosis. Healthcare prescribers may prescribe nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or stronger pain medications, oral contraceptives, anti-prostaglandins, tranexamic acid, danazol, aromatase inhibitors, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, or a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device system to treat symptoms [7,8,9]. Therapeutic minimally invasive procedures, such as endometrial ablation, may have a higher rate of failure for women with adenomyosis [10]. When there is focal adenomyosis, laparoscopic myometrial electrocoagulation or excision can be used [8]. Hysterectomy is an option if fertility is not an issue, given other treatments may fail [8]. Based on a targeted literature review, no patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures for adenomyosis have been developed, and information regarding its specific signs, symptoms, and impacts characterized by women with adenomyosis is limited. Given the increasing emphasis of the FDA on patient-centred outcomes [11], a validated PRO measure could be highly supportive of regulatory approval of novel treatments.

Improved understanding of women’s experience with adenomyosis will support the development of informed, responsive PRO measures to help characterize the response to novel treatment approaches for adenomyosis. The objective of this study was to conduct qualitative interviews to characterize the symptoms, impacts, and disease experience of women with adenomyosis.

1.1 Methods

1.1.1 Study Design

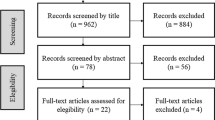

This was a qualitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study in women with adenomyosis (GSK study: HO-15-15667). Qualitative analyses were conducted that followed the principles of the grounded theory method [12] as well as methods suggested by Patton [13]. The key tenet of the grounded theory method (originally developed by Glaser and Strauss [14]) is that the concepts that emerge through analysis of the data are “grounded” in the experiences of the respondents, and the results can be used to develop a theoretical understanding of the content areas under investigation. In this study, the preliminary stage of concept analysis was performed to identify the concepts/symptoms of interest. A card-sorting exercise based on pre-identified symptoms (from literature review) was conducted to provide additional structured information regarding symptom severity and impact.

Institutional review board approval was received from the Western Institutional Review Board, Puyallup, WA, USA, and Ethical Independent Review Services, Independence, MO, USA; all participants provided written informed consent prior to being interviewed. The study was conducted in alignment with the recommendations of the FDA PRO guidance [11] and the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Good Research Practices Task Force for establishing and reporting the content validity of PRO instruments [15].

Participants took part in a single 1:1 face-to-face or telephone interview, conducted between September and December 2015 by employees of Evidera (Table 1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). Participants were informed of the aims of the study, the study sponsor, and the role of the interviewer in the study. Participants had no relationship with the interviewer prior to the interview; the interviewer asked some condition-specific questions at the beginning of the interview to gain a high-level understanding of the participants clinical history. Interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide developed based on a targeted literature review to identify adenomyosis symptoms and impacts, and feedback from two expert physicians and two patients. Interviews consisted of concept elicitation, a card-sorting exercise, and completion of a sociodemographic form, and lasted up to 2 h. For the concept elicitation, women were asked about their general experiences with adenomyosis signs and symptoms and how adenomyosis impacts their day-to-day activities. Initially, women were encouraged to spontaneously report their experiences; interviewers then probed participants using a pre-specified list. To ensure that all concepts important to the participants were included, and to minimize bias, concept saturation for the concept-elicitation phase was determined using a saturation grid [15, 16].

For the card-sorting exercise, participants were provided with 41 cards (Table 2 in the ESM), each listing a symptom of adenomyosis (identified from literature and the prior patient and physician expert interviews). For participants taking part in telephone interviews, the cards were sent prior to the interview. Participants were asked to sort the cards by symptoms that they did and did not experience. For the symptoms they did experience, they were asked to sort the cards three times; by severity, by the level of impact in their daily lives, and by occurrence in relation to their menstrual cycle. For the telephone interviews, participants provided the order of the cards in response to the questions over the phone.

1.2 Participants

Women were recruited from five clinics across the USA (Philadelphia, PA; Boise, ID; Durham, NC; New Brunswick, NJ; Virginia Beach, VA) and through targeted pop-up advertisements on HealthUnlocked, a social network site that provides a forum for patients to discuss health-related issues. Participants were aged 18–55 years and pre-menopausal with a history of regular menstrual cycles (occurring every 21–35 [± 5] days). Participants recruited at clinics had a diagnosis of adenomyosis according to transvaginal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). For participants recruited at a clinical site, the clinic completed a clinical case report form that included the participant’s clinical history and comorbid medical conditions. Participants recruited through advertisements self-reported their adenomyosis that had been diagnosed by their physicians. Key exclusion criteria for participants recruited at clinics included history of an endometrial ablation or uterine artery embolization within 6 months of enrollment; currently pregnant or less than 6 months postpartum; confirmed rectovaginal endometriosis; MRI demonstrating uterine fibroids as the dominant process (presence of sub-mucosal fibroids or intramural fibroids ≥ 10 cm; sub-serosal uterine fibroids were acceptable); malignant disease of the uterus, ovary or cervix; ovarian lesions suggestive of endometriosis > 3 cm in diameter; or the presence of uterine polyps. In addition, participants recruited through advertising with any diagnosis of uterine fibroids were excluded.

1.3 Data Analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded, and audio recordings were transcribed. Participant-identifying information was removed before analysis. Data were analyzed using ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis software, version 7.1.6. Transcripts were not provided to participants, and participants were not asked to provide feedback on the findings.

A coding dictionary was developed for the study based on the interview guide. All transcripts were coded and reviewed by three trained personnel according to the following protocol. Two of the personnel independently coded each interview transcript. A post-coding comparison and reconciliation was conducted by the third member of the team. Relevant codes were attached to each concept mentioned within each transcript; where necessary, new codes were added to the coding dictionary. Once all transcripts were coded, a quality-control check was performed. All utilized codes were then entered into a saturation grid to track the concepts identified in each interview and to determine when saturation (the interview at which no novel concepts were gathered) was reached [17].

2 Results

2.1 Study Population

In total, 31 women participated in the study; 27 were recruited from clinical sites and four were recruited through HealthUnlocked (Table 1). Two participants took part in face-to-face interviews; the remaining 29 interviews were undertaken over the telephone. With the exception of William R. Lenderking (a senior clinical psychologist and the project director), all interviewers were women. Dr. Lenderking conducted 8 interviews over the telephone; these participants were explicitly asked whether they were uncomfortable being interviewed by a male, and they raised no issues. No effect on the women’s candor was noted as a function of the sex of the interviewer.

Participants reported the mean (range) duration since they first experienced adenomyosis symptoms as 5.7 (0–23) years, and 41.9% rated their adenomyosis as severe or very severe (Table 2). For participants recruited from clinics, clinicians reported a mean (range) duration since adenomyosis diagnosis of 1.2 (0–6) years. The majority of women (88.9%; n = 24/27) were diagnosed via transvaginal ultrasound, and 11.1% (n = 3/27) were diagnosed via MRI.

2.2 Concept Elicitation: Symptoms

More than 50 different symptoms of adenomyosis were reported, the most common of which were heavy menstrual bleeding (87%), cramps (84%), blood clots during menstrual bleeding (84%), bloating (55%), and low energy/fatigue (52%) (Table 3). The saturation grid demonstrated that 87% of concepts were reported after 7 interviews, and saturation was reached after 30 interviews (Table 3 in the ESM). New symptoms after the seventh interview included blood in the urine, constipation, difficult or painful defecation, ovarian pain, and diarrhea.

2.3 Concept Elicitation: Impacts

More than 30 impacts of adenomyosis were reported; the most common were burdensome self-care hygiene (71%), fatigue/low energy (71%), and impacts on leisure/social activities (65%), household/activities of daily living (61%), travel (61%), and physical activities (61%) (Table 3). Many participants reported that fatigue was more of an issue during their menstrual periods. Saturation on impacts was reached after 25 interviews, and 78% of impacts had been reported after 5 interviews (Table 4 in the ESM). New impacts after the fifth interview included eating (primarily feeling too nauseous to eat), stress, anxiety (e.g., the fear of having a bleeding accident, and concern that they may have a condition more severe than adenomyosis), and loss of control/helplessness.

2.4 Card Sorting

All 41 symptoms presented in the card-sorting exercise were experienced by at least one participant (Fig. 1a). The most commonly endorsed symptoms, pain during menstruation/menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) and heavy menstrual bleeding, were also the symptoms most frequently rated as severe (70% [n = 21/30] and 76% [n = 22/29], respectively), along with longer cycles (84% [n = 16/19]; Fig. 1b).

The symptoms with the highest impact were heavy menstrual bleeding (68% [n = 19/28]), pain (64% [n = 16/25]), longer cycles (63% [n = 12/19]), and pain during menstruation/menstrual cramps (60% [n = 18/30]; Fig. 1c).

Symptoms most commonly reported to be present all month regardless of menstruation included pain during intercourse (dyspareunia 88% [n = 15/17]); bleeding or spotting between periods (79% [n = 11/14]); waking at night to urinate (76% [n = 13/17]); dryness/tightness in the vaginal region (70% [n = 7/10]); and tingling or numbness in hands or feet (69% [n = 9/13]). The symptoms reported by the highest proportion of women as being experienced only during menstruation included heavy menstrual bleeding (100% [n = 29/29]), blood clots during menstrual bleeding (100% [n = 28/28]), and difficulties with menstruation (100% [n = 24/24]).

3 Discussion

Adenomyosis is not well characterized and likely under-diagnosed by clinicians. A literature search revealed a limited understanding of the signs, symptoms, and impacts of the condition, with little evidence derived directly from women with adenomyosis. To improve management of adenomyosis, it is important to understand the experiences of women with this condition. This study reports the symptoms and impacts of adenomyosis from the patient perspective.

The 31 participants in the study reported over 50 different symptoms, and all reported multiple symptoms. The most common symptoms were associated with bleeding and pain. The biggest impacts for women concerned self-care hygiene, fatigue/low energy, and leisure/social activities. In spite of the variability of symptoms and impacts reported, 87% of symptoms were reported after 7 participant interviews, and 78% of impacts were reported after just 5 interviews. This suggests that, although there is variability and a wide range of symptoms and impacts, the overall symptom profile of adenomyosis was fairly consistent in this study population.

In addition to the concept elicitation, the card-sorting exercise enabled us to ask women to review a predefined list of symptoms. Given the time constraints of the interviews and the wide range of symptoms, this allowed us to investigate symptoms that women may not have originally reported during the concept elicitation but did associate with their adenomyosis when prompted by the cards. The results of the card-sorting exercise reinforced the concept-elicitation findings.

Although there are some similarities in the pathogenesis of adenomyosis and endometriosis [6], adenomyosis results from the infiltration of basal endometrium into the underlying myometrium [18], whereas in endometriosis there is endometrial gland and stroma-like tissue outside of the uterus [19]. In reviewing the literature, the authors are not aware of other studies that have comprehensively investigated the symptoms and impacts of adenomyosis from the patient perspective. However, previous studies in women with endometriosis have identified similar symptoms, demonstrating overlap between the two conditions. Symptoms of adenomyosis, such as pain, fatigue, bloating, and abnormal uterine bleeding are commonly reported by women with endometriosis [20, 21]. Although there is overlap between the type of symptoms, particularly pain, experienced in adenomyosis and endometriosis, there may be substantial differences in the character of the pain; further research is required to determine whether this is the case.

Many of the physical and psychological impacts of adenomyosis are also experienced by women with endometriosis. Importantly, burdensome self-care/hygiene, the most commonly reported impact of adenomyosis, has not been associated with endometriosis and is likely due to heavy menstrual bleeding. Furthermore, fatigue/low energy, another highly reported impact of adenomyosis, appears to be a less common impact of endometriosis [21]. In contrast, both adenomyosis and endometriosis have been shown to negatively impact overall quality of life, activities of daily living, social activities, work/education, finances, and sleeping, as well as psychological well-being in terms of frustration, depression, and anxiety [20, 21].

This study provides important information regarding the symptoms and impacts of adenomyosis from the perspective of women; however, it does have some limitations. The majority of women in the study were diagnosed with adenomyosis using transvaginal ultrasound or MRI; however, diagnostic information was not available for the small number of participants (n = 4) recruited through HealthUnlocked, which could affect the reliability of the case definition. The requirement for women recruited from clinics to have a diagnosis confirmed by imaging may have resulted in the exclusion of patients with mild adenomyosis (43% of the study population had severe/very severe adenomyosis); therefore, the results may be less representative of women with mild adenomyosis. A small number of participants (four recruited from clinics and two from HealthUnlocked) had diagnoses of both adenomyosis and endometriosis, so not all of the symptoms and impacts reported by these participants may have been due purely to adenomyosis. The small number of participants with both conditions means it was not possible to compare the symptoms of these patients with those of patients with adenomyosis alone. Furthermore, some of the women with adenomyosis may have undiagnosed endometriosis. Indeed, there is a recognized association between having adenomyosis and endometriosis [19]. Finally, the study population consisted of women in the USA only; therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to women from other countries.

4 Conclusion

Initiatives to understand women’s experiences with adenomyosis will support the development of informed, responsive PRO measures to help characterize the response to novel treatment approaches. This study provides a first step in understanding the perspectives and experiences of women with adenomyosis.

References

Bird CC, McElin TW, Manalo-Estrella P. The elusive adenomyosis of the uterus: revisited. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;112:583–93.

Benagiano G, Habiba M, Brosens I. The pathophysiology of uterine adenomyosis: an update. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:572–9.

Peric H, Fraser IS. The symptomatology of adenomyosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20:547–55.

Naftalin J, Hoo W, Pateman K, Mavrelos D, Holland T, Jurkovic D. How common is adenomyosis? A prospective study of prevalence using transvaginal ultrasound in a gynaecology clinic. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:3432–9.

Taran FA, Stewart EA, Brucker S. Adenomyosis: epidemiology, risk factors, clinical phenotype and surgical and interventional alternatives to hysterectomy. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde. 2013;73:924–31.

Di Donato N, Seracchioli R. How to evaluate adenomyosis in patients affected by endometriosis? Minim Invasive Surg. 2014;2014:507230.

Cho S, Nam A, Kim H, Chay D, Park K, Cho DJ, et al. Clinical effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device in patients with adenomyosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(373):e1–7.

Levgur M. Therapeutic options for adenomyosis: a review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276:1–15.

Hong SCKC. An update on adenomyosis uteri. Gynecol Minim Invas Ther. 2016;5:106–8.

Simon RA, Quddus MR, Lawrence WDCJS. Pathology of endometrial ablation failures: a clinicopathologic study of 164 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2015;34:245–52.

FDA. Guidance for industry on patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Fed Regist. 2009;74:65132–3.

Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008.

Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods Third ed. Sage Publciations; 2002.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967.

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, et al. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force Report: Part 1—eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14:967–77.

Leidy NK, Vernon M. Perspectives on patient-reported outcomes. PharmacoEconomics. 2008;26:363–70.

Rothman M, Burke L, Erickson P, Leidy NK, Patrick DL, Petrie CD. Use of existing patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments and their modification: The ISPOR good research practices for evaluating and documenting content validity for the use of existing instruments and their modification PRO Task Force report. Value Health. 2009;12:1075–83.

Kunz G, Beil D, Huppert P, Noe M, Kissler S, Leyendecker G. Adenomyosis in endometriosis—prevalence and impact on fertility. Evidence from magnetic resonance imaging. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2309–16.

Sourial S, Tempest N, Hapangama DK. Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:179515.

Moradi M, Parker M, Sneddon A, Lopez V, Ellwood D. Impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health. 2014;14:123.

Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, Denny E, Mitchell H, Baumgarten M, et al. The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a critical narrative review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:625–39.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all women who participated in the interviews.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LMN, LB, SP, MBE and MC contributed to the conception/design of the study and analyis/interpretation of the results. WRL, RP and ZB contributed to the conception/design of the study, acquisition of data (including conducting interviews with the study participants), and analyis/interpretation of the results. ASL contributed to the conception/design of the study, acquisition of data, and analyis/interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to the preparation of this manuscript. Editorial assistance (in the form of writing assistance, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, grammatical editing, and referencing) was provided by Katie White, PhD, Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GSK.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). Evidera, funded by GSK, and GSK contributed to the design of the study and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Conflict of interest

Linda M. Nelsen, Shibani Pokras, Mary Beth Enslin, and Melisa Cooper are employees of GSK. William R. Lenderking, Robin Pokrzywinski, and Zaneta Balantac are full-time employees of Evidera, a company that provides works for hire to the pharmaceutical industry. William R. Lenderking owns stock in Pfizer Inc. as a former employee. Libby Black is a Global Health Outcomes contract researcher for Recro Pharma, Inc. and was employed as a contractor by GSK at the time the study was conducted. She owns stock in GSK. Andrea S. Lukes has acted as a consultant for and received grants from GSK.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nelsen, L.M., Lenderking, W.R., Pokrzywinski, R. et al. Experience of Symptoms and Disease Impact in Patients with Adenomyosis. Patient 11, 319–328 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0284-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0284-2