Abstract

Background

Co-formulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF; Stribild®) is a guideline-recommended regimen for HIV treatment-naïve patients and a switch option for virologically suppressed patients.

Objective

The purpose of this analysis was to understand how HIV patients’ symptoms change after switching to Stribild® versus continuing a regimen consisting of a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) with emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Methods

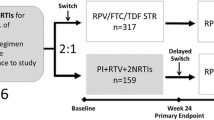

A secondary analysis was conducted of the STRATEGY-NNRTI study (GS-US-236-0121), a randomized, open-label, phase IIIb trial of HIV-infected adults who were taking an NNRTI plus FTC/TDF and were randomly assigned (2:1) either to Stribild® (‘switch’) or to continue on their existing regimen (‘no-switch’). Logistic regressions and longitudinal modeling were conducted to evaluate the relationship of treatment with bothersome symptoms. These models adjusted for age, sex, race, number of bothersome symptoms at baseline, Veterans Aging Cohort Study Risk (VACS) Index score, years since HIV diagnosis, and first antiretroviral therapy use, NNRTI type, serious mental illness, and baseline depression and health-related quality of life (HRQL) scores.

Results

At baseline, the prevalence of nightmares, vivid dreams, weird/intense dreams, muscle aches/joint pain, and fevers/chills/sweats was greater in the switch group. The prevalence of nightmare, vivid dreams, weird/intense dreams, dizzy/lightheadedness, fatigue/loss of energy, and pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet deceased in the switch group at week 4, and these benefits were maintained over time. Nervous/anxious, drowsiness, trouble remembering, off balance, and body changes decreased in the switch group at week 4 but were not maintained over time. Difficulty sleeping, diarrhea/loose bowels, and bloating did not differ in prevalence at week 4 or 48, but longitudinal models suggested differences between groups over time. HRQL did not differ between groups and was unchanged over time.

Conclusions

In this study sample, a switch to co-formulated EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF was associated with significant persistent improvements in six patient-reported HIV symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Little is known about how HIV patients’ symptoms change after switching to Stribild® versus continuing a regimen consisting of a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) with emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. |

In this study, switching to Stribild® was associated with significant persistent improvements from baseline to 48 weeks in six patient-reported HIV symptoms: nightmares, vivid dreams, weird/intense dreams, dizzy/lightheadedness, fatigue/loss of energy, and pain/numbness/tingling in hands/feet. |

Higher levels of satisfaction with treatment were evident in patients who switched to Stribild® compared with the no-switch group at the first follow-up visit and subsequent measurement time point. |

1 Introduction

Effective management of HIV-associated symptoms and antiretroviral (ARV)-associated adverse effects can improve health-related quality of life (HRQL) [1–3]. In addition, well-tolerated therapies improve treatment adherence and persistence [4–6]. Given current therapies have extended HIV survival [7], improving patients’ daily lives by minimizing and managing symptoms is of considerable importance [8].

One approach to improve drug-associated side effects and tolerability in virologically suppressed patients is to switch ARV therapy. Single-tablet regimens can be an attractive switch option because of their inherent convenience. The co-formulated regimen of elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF; Stribild® [STB]) is indicated as a switch option for virologically suppressed HIV-infected adults taking a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) with FTC and TDF [9, 10]. Patients on an NNRTI-containing regimen might be appropriate candidates for treatment modification to an NNRTI-sparing regimen like STB if they have bothersome neuropsychiatric side effects such as anxiety, insomnia, dizziness, and abnormal dreams [11]. Other commonly recognized symptoms associated with contemporary NNRTI-containing regimens include skin reactions, fever, fatigue, hand/foot pain, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and headaches [12].

The patient symptom experience after switching to a treatment like STB may inform or predict treatment adherence, persistence, quality of life, and/or treatment satisfaction; however, these associations are rarely examined in large randomized clinical trials evaluating HIV therapies [13, 14]. Therefore, the purpose of this secondary analysis was to evaluate the patient HIV symptom experience and HRQL over 48 weeks among those who switched to STB as compared with those who continued their NNRTI plus FTC/TDF regimen.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

The study design and patient recruitment have been previously described [10] but are summarized here. STRATEGY-NNRTI was an international, open-label, randomized study to evaluate the efficacy (non-inferiority), safety, and tolerability of switching to the single-tablet regimen STB, containing EVG 150 mg, COBI 150 mg, FTC 200 mg, and TDF 300 mg, from a regimen consisting of an NNRTI plus FTC/TDF (NNRTI + FTC/TDF) in virologically suppressed HIV-1 infected adults. A total of 439 participants were randomly assigned (2:1) and dosed; 292 switched to STB (‘switch’ group) and 147 continued on their baseline NNRTI-containing regimen (‘no-switch’ group). After exclusions, 291 and 143 participants, respectively, were analyzed in the modified intention-to-treat population. Post-baseline study visits occurred at weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48. The study design was open-label; participants and investigators were not masked to group allocation.

2.2 Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Demographics (sex, age, race, ethnicity) and clinical characteristics (serious mental illness, CD4 cell count, asymptomatic status, years since HIV diagnosis, years since first ARV therapy use, on first ARV regimen, and NNRTI at randomization) were collected. Serious mental illness was defined as having a diagnosis of one or more of the following conditions based on medical chart review: major depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or other psychosis.

The Veterans Aging Cohort Study Risk (VACS) Index was calculated to quantify the overall mortality risk associated with HIV. The VACS Index is a summary score based on age, CD4 count, HIV-1 RNA, the Fibrosis (FIB)-4 score, creatinine, and viral hepatitis C infection to predict all-cause and cause-specific mortality and other outcomes in those living with HIV infection and mortality among those without HIV infection [15, 16]. The FIB-4 score, computed using age, platelets, and aspartate and alanine transaminase values provides an estimate of the degree of liver fibrosis in HIV and hepatitis C virus co-infected patients [17].

2.3 Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs)

2.3.1 Dependent Variables

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) used as dependent variables in this secondary data analysis included the following.

2.3.1.1 Modified HIV Symptom Index (HIV-SI)

A modified version of the HIV Symptom Index (HIV-SI) was used to evaluate symptom-specific bother. The HIV-SI [16], which was developed to assess 20 commonly experienced symptoms based on literature review and clinical and advisory board feedback, is supported by evidence of good construct validity and has been considered the gold standard in contemporary HIV symptom research [3]. Patients are asked about their experience of each of the symptoms during the past 4 weeks on a five-point Likert scale. Response options and scores are as follows: (0) “I don’t have this symptom”; (1) “I have this symptom and it doesn’t bother me”; (2) “I have this symptom and it bothers me a little”; (3) “I have this symptom and it bothers me”; (4) “I have this symptom and it bothers me a lot”.

Modifications to the instrument included the following. The question “Nausea or vomiting?” was separated into two discrete questions (“Nausea?” and “Vomiting?”) to distinguish the difference in these symptoms, as nausea is more common than vomiting in patients taking multiple HIV medications. The question “Felt sad, down or depressed?” was removed and substituted with a more specific questionnaire on depression—the Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression (CES-D; described below). In order to identify changes in drug-associated neuropsychiatric symptoms, which have been well described in relation to efavirenz [11], additional symptoms as identified in the US prescribing information for efavirenz (Sustiva) were added to the instrument for the present study. Six questions were added to assess symptoms of dreams (“Nightmare?”, “Vivid dreams?”, and “Weird or intense dreams?”) and balance (“Feeling off balance?”, “Felt drowsy?”, and “Unsteady walking?”).

Consistent with prior analyses by Edelman et al. [13], symptoms were dichotomized as bothersome (2, 3, or 4) versus not bothersome (0, 1) in order to provide information about symptoms not just present but bothersome, and thus clinically relevant to treatment decisions. In addition, the overall bothersome symptom count at baseline was generated by counting the number of individual symptoms scored as ‘bothered’ and used as a covariate in regression analyses and longitudinal modeling of baseline to week 48 data.

2.3.1.2 Short Form-36 (SF-36)

The physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) from the Short-Form (SF)-36 were used to evaluate HRQL [18]. The SF-36 is supported by extensive evidence of good psychometric properties in a range of therapeutic areas [19]. Scores for the PCS and MCS range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better HRQL.

2.3.2 Descriptive Measures

PROs used to provide descriptive information and as covariates in regression and longitudinal analyses of baseline to week 48 data included the following: (1) the CES-D, a 20-item instrument used to measure depressive symptomatology and supported by evidence of reliability and validity in HIV clinical trials [3, 20]; (2) the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), a 40-item measure that assesses trait and state anxiety and has demonstrated good psychometric properties in a range of therapeutic areas [21]; (3) the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Adherence Questionnaire [22], a validated instrument that correlates significantly with Medication Event Monitoring System caps and pharmacy data, used to assess patient-reported adherence to their ARV regimen using a linear scale (0–100 %) to indicate the percentage of medication taken in the last 30 days; (4) and the HIV Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (HIVTSQ), a 10-item instrument with five items assessing general treatment satisfaction and five items assessing treatment ease [23] that is supported by evidence of good internal consistency reliability [24]. The Status form (HIVTSQs) was used at baseline and asks about “now”, and the change form (HIVTSQc), in which items state “compared to before”, was used at week 4 and week 24. The response options for the HIVTSQs form are anchored at 6 and 0, and those for the HIVTSQc form range from values of 3 to −3. The total score ranges from 0 to 60 for the status form and from −30 to 30 for the change form, with higher positive scores indicating more/improved satisfaction and higher negative scores indicating greater dissatisfaction.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Questionnaires were submitted by 98 % of enrolled patients at baseline and by 90 % at week 48; the decline was partly due to patients who left the study. Of questionnaires received, roughly 300 items had missing values, of a total of 340,000 records (<0.1 %). Following recommendations from the instrument developer, Amy Justice (Professor of Medicine and Public Health—Yale School of Medicine), the following imputation rules were applied to the HIV-SI data. If multiple responses were provided for a single item, the most severe (maximum) of the responses was used. Where single items were left blank, yet other items were completed, the missing value was imputed to “I do not have this symptom”, a score of 0.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample at baseline, including demographic and clinical characteristics and PROs. Unadjusted and adjusted analyses at week 4 and week 48 were completed to evaluate the relationship of treatment with the probability of experiencing HIV-SI items and physical and mental HRQL as evaluated by the SF-36 PCS and MCS, respectively. Consistent with prior work by Edelman et al. [13], HIV-SI items were modeled as binary outcomes using a logistic regression model analysis, and the PCS and MCS were modeled using general linear regression models. Each model included treatment as the independent variable and covariates that were selected from a number of potential variables that were evaluated for multicollinearity.

Furthermore, generalized linear mixed-model regressions were conducted to evaluate changes in the prevalence of each of the HIV symptoms over 48 weeks. The functional form of the change pattern was assessed visually from the observed prevalence in each group. Linear and quadratic patterns were tested to determine optimal fit, ultimately favoring a linear function. Given the open-label nature of the study and the potential for a response bias, we decided to model weeks 4 through 48 and include baseline as a covariate. To assess the possibility that the effect of treatment may itself vary over time, the models included an interaction between treatment and time in addition to the indicator of treatment group. Continuous variables were mean centered for ease of interpretation and model fit. No model reduction was performed; all predictors were retained in each model. The fit of the derived models was compared with a simple unadjusted model that included time and treatment along with a random intercept to account for the longitudinal nature of the data. The comparison was based on Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

A similar modeling approach was used to model the changes over time in the SF-36 PCS and MCS, which used a linear mixed-model regression.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline Characteristics

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were similar in the two treatment groups (Table 1). At randomization 74 % of patients were receiving the co-formulated regimen consisting of TDF, FTC, and efavirenz (i.e., Atripla). In the switch group versus the no-switch group, participants had a mean duration of 6 versus 5 years since HIV diagnosis, 4 versus 3 years since first ARV therapy use, and 77 versus 80 % had asymptomatic disease, respectively. HRQL as evaluated by the SF-36 PCS and MCS was high on the baseline regimen in both groups (switch group: mean [standard deviation {SD}] PCS 55.3 [5.9], MCS 50.0 [10.4]; no-switch group: PCS 56.0 [4.7], MCS 51.7 [9.0]). On average, participants in both groups had similar CES-D and STAI scores across visits that reflected low levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms.

3.2 Descriptive Analysis of PRO Measures

A statistically significant difference was observed in the prevalence of symptom bother for five HIV-SI items (nightmares, vivid dreams, weird/intense dreams, muscle aches/joint pain, and fevers/chills/sweats) at baseline (Table 2). While the no-switch group tended to remain steady over time and/or increase at week 4, a total of 12 symptoms in the switch group decreased significantly from baseline to week 4. These improvements compared with baseline remained significant at week 48 for eight symptoms (nightmare, vivid dreams, weird/intense dreams, dizzy/lightheadedness, nervous/anxious, difficulty sleeping, diarrhea/loose bowels, and fever/chills/sweats). Importantly, this descriptive analysis evaluated differences in prevalence for each study visit in relation to baseline and did not control for differences due to demographic and clinical factors. Trends over time controlling for baseline differences for these HIV symptoms are further discussed in relation to the results of the regression and longitudinal analyses.

Patient-reported treatment adherence was ≥98 on the 100-point VAS across study visits in both treatment groups (see Table 1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). Treatment satisfaction was similar between groups at baseline. At weeks 4 and 24, the mean HIVTSQc scores were positive for both groups, indicating greater satisfaction with treatment; however, the scores for the switch group were statistically significantly higher than those for the no-switch group (week 4: switch group mean [SD] 18.7 [11.6], no-switch group 13.4 [13.2]; week 24: switch group mean [SD] 21.7 [10.2], no-switch group 15.1 [13.0]).

3.3 Associations between HIV-SI Bothersome Symptoms and Treatment in Logistic Regression Models and Longitudinal analyses

The elimination of potential covariates from models was informed by item distributions and multicolinearity. The final model included treatment group (no-switch vs. switch) as the independent variable and the following covariates: age, sex, race (white vs. non-white), HIV-SI symptom count at baseline, VACS Index score, years since HIV diagnosis, years since first ARV therapy use, NNRTI (non-EFV), serious mental illness, baseline CES-D score, and baseline MCS and PCS scores. Table 2 in the ESM present results that show that switching to STB was associated with lower probabilities of experiencing 11 HIV symptoms at one or more time points in adjusted logistic regression models.

The prevalence of bothersome symptoms over time was evaluated using mixed-effects logistic models with the same predictor list specified above. In all instances, the BIC of the multivariate model showed a substantial improvement in fit over the simple unadjusted model with treatment only, suggesting that bothersome symptom prevalence was associated with at least some of the predictors included in the model.

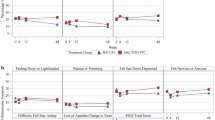

The adjusted longitudinal models revealed a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of several symptoms between the switch and no-switch groups over time. A complete table showing the coefficients, including findings for main effects and time by treatment interactions, is provided in Table 3 in the ESM. Table 3 categorizes groups of symptoms with similar patterns of statistically significant results from the regression and longitudinal analyses. Figures 1 and 2 plot the prevalence of symptoms among the categorized groups at each data collection time point and indicate the statistically significant Chi-squared test for difference between the switch and no-switch groups. In Group 1, the prevalence of nightmare, vivid dreams, weird/intense dreams, dizzy/lightheadedness, fatigue/loss of energy, and pain/numbness/tingling in the hands/feet were each significantly lower in the switch group than in the no-switch group at week 4 (and also at week 48 for nightmare, vivid dreams, weird/intense dreams, dizzy/lightheaded, and pain/numbness/tingling in hands and feet). Furthermore, the switch group maintained its advantage over time, or declined equally with the no-switch group in prevalence as demonstrated in the longitudinal analyses for these symptoms (Fig. 1). In Group 2, the prevalence of nervous/anxious and drowsiness was significantly lower in the switch group at week 4; however, the switch group lost its advantage over time as indicated by the significant time-by-treatment interaction from the longitudinal analyses (Fig. 2). For Group 3, HIV symptoms (difficulty sleeping, diarrhea/loose bowels, bloating/pain/gas in stomach), no statistically significant differences in prevalence were observed at the week 4 or 48 time points by treatment group; however, the longitudinal analyses revealed that, compared with baseline, the prevalence of these symptoms decreased over time and the decrease differed by treatment group (Fig. 2). The prevalence of difficulty sleeping and diarrhea/loose bowels was lower in the switch group over time, while bloating/pain/gas in stomach decreased in prevalence in the no-switch group. For Group 4 (trouble remembering, feeling off balance, and changes in body composition), the lower prevalence in the switch group that was statistically significant at week 4 was not observed longitudinally from week 4 to week 48 (Fig. 2).

3.4 Associations between Health-Related Quality-of-Life Outcomes (SF-36 Physical Component and Mental Component Scores) and Treatment in Linear Regression Models and Longitudinal Analyses

HRQL was maintained in subjects who switched to STB and was comparable to those who continued the NNRTI, FTC, and TDF regimen. Treatment was not associated with HRQL as assessed by the PCS or MCS at week 4 or week 48 in the unadjusted or adjusted linear multiple regression analyses or in the longitudinal modeling of these outcomes (see Table 4 in the ESM).

4 Discussion

In this study, the first prospective, randomized HIV switch trial to use the modified HIV-SI to assess the symptom experience of patients switching off an NNRTI, a switch to STB was associated with better treatment satisfaction, improvements in six patient-reported HIV symptoms that were maintained over the 48-week study period compared with continuation of an NNRTI with FTC and TDF, and no differences or changes in HRQL. Statistical analyses included cross-sectional regressions using data from two key time points in the trial: week 4, the first follow-up visit after switching to STB and the earliest opportunity to see a potential treatment benefit; and week 48, a primary efficacy outcome study visit. Mixed-effects longitudinal modeling was also conducted in order to better understand whether early reductions were maintained across the six follow-up study visits.

Importantly, rather than evaluating the presence of HIV symptoms, this secondary analysis identified those symptoms that bothered the patient and included questions that assessed well-described side effects of efavirenz, including abnormal dreams (vivid dreams, nightmare, weird/intense dreams) and drowsiness (feeling drowsy, feeling off balance, unsteady walking). Abnormal dreams were asked about in three different ways to capture the most specific accurate interpretations of those symptoms given that patients were completing a self-administered instrument for data collection. The rationale for including three questions on drowsiness was to further understand whether patients were bothered by other effects on equilibrium and balance beyond ‘dizziness’, as suggested by post-marketing reports of efavirenz [11].

Building on the descriptive analysis results—which showed the switch group had a higher prevalence in five HIV-SI items at baseline and significant reductions in eight HIV symptoms at week 48—regression analyses revealed that switching to STB from an NNRTI plus FTC/TDF regimen was associated with decreases in the frequency of 11 HIV symptoms at week 4; however, those differences were not always maintained over time, setting some symptom experiences apart from others. The most clear treatment benefits are for the six HIV symptoms categorized as group 1: nightmare, vivid dreams, weird/intense dreams, dizzy/lightheadedness, fatigue/loss of energy, and pain/numbness/tingling in the hands/feet. Each of these symptoms had a significantly lower prevalence in the switch group than in the no-switch group at week 4, and over time the switch group maintained its advantage or declined equally with the no-switch group in terms of prevalence. While symptom declines tended to taper off toward the end of the follow-up period, the prevalence of five of these symptoms—nightmare, vivid dreams, weird/intense dreams, dizzy/lightheadedness, and pain/numbness/tingling in the hands/feet—was significantly lower in the switch group than in the no-switch group in the logistic regression analysis conducted at week 48. The statistically higher prevalence of nightmare, vivid dreams, and weird/intense dreams in the switch group as compared with the no-switch group at baseline should be considered in interpreting the results, as there could be potential for bias. This concern is most relevant to the baseline to week 4 change in prevalence: because the switch group was starting from a higher prevalence rate at baseline, it had a greater range of improvement to achieve.

Some of the symptoms with the strongest evidence of decline—nightmare, vivid dreams, and weird/intense dreams—are not only bothersome but costly. Simpson et al. [25] looked at the incidence and cost of 11 adverse events (rash, nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, sleep-related symptoms, hepatotoxicity, lipid disorders, depression, anxiety, and suicide or self-injury) among NNRTI users and found sleep-related adverse events to be the most expensive with regard to outpatient services, with a mean cost per episode of $US6438 (interquartile range 615–5882; median 1785). Further, the overall mean healthcare cost of sleep-related symptoms ($US8307) was second to that of nausea and vomiting ($US12,833) [25].

In contrast to evidence of early sustained improvements found for symptoms in group 1, the impact of treatment on symptoms in groups 2–4 is not completely clear. For nervous/anxious and drowsiness, statistically significant time-by-treatment interactions, in addition to significant main effects for treatment were present, indicating the switch group lost its prevalence advantage over the no-switch group over time. These results may be explained in part by the fact that, at week 4, not only had the switch group improved significantly, but the no-switch group worsened substantively (statistically significant for drowsiness); however, this trend did not continue longitudinally. For difficulty sleeping, diarrhea/loose bowels, and bloating/pain/gas in stomach (group 3), longitudinal modeling showed statistically significant main effects for treatment, indicating a difference in the prevalence trajectories of the two groups, while no significant differences between groups were observed at weeks 4 and 48. The lower prevalence of difficulty sleeping in the longitudinal model favored the switch group and was consistent with findings for other sleep-related symptoms. The prevalence over time of diarrhea/loose bowels was also lower in the switch group, while the prevalence of bloating/pain/gas in the stomach over time remained the same in the switch group and was lower in the no-switch group. Given there was no change in therapy for the no-switch group, it is somewhat counterintuitive that there was a decrease in the prevalence of bothersome bloating/pain/gas in the stomach for this group. The difference in prevalence of group 4 symptoms (trouble remembering, feeling off balance, and changes in body composition), which significantly favored the switch group, was isolated to week 4. That these symptoms are not commonly described symptoms of any NNRTI weakens the case for there being a clear treatment benefit.

While differences in the prevalence of some HIV symptoms were observed between groups, there were 12 symptoms for which differences in the patterns of prevalence were not detected. In adjusted models, reductions were essentially parallel over time for problems with sex, skin problems/rash/itching, muscle aches/joint pain, fevers/chills/sweats, headaches, hair loss or changes, nausea, coughing/trouble breathing, loss of appetite/food taste, unsteady walking, weight loss/wasting, and vomiting. The statistically significant associations found among multiple covariates with these bothersome symptoms (e.g., race, baseline VACS Index, years since HIV diagnosis, and years since first ARV therapy) highlights other important associations to consider.

HRQL outcomes (SF-36 MCS and PCS scores) were similar for participants who switched to STB and for those who remained on their existing NNRTI-containing regimen. Patients in both groups maintained their mental and physical health functioning throughout the treatment study. These findings are consistent with a 2014 review [26] that found that, of ten trials including patients on NNRTI-containing regimens that measured patient-reported HRQL, half showed no significant difference on any measured HRQL domain—a trend that was particularly apparent when less sensitive tools evaluating general HRQL were used.

A notable strength of the present study is the use of PRO tools, providing insight into patient-reported symptoms that may be under-reported by clinicians [2]. The use of longitudinal modeling of patient-reported data contributes a richer understanding of the prevalence of HIV symptoms over time after switching ARV therapy (i.e., relation to treatment) and, to our knowledge, has not been conducted in prior HIV clinical trials. The categorization of results based on cross-sectional regression modeling and longitudinal modeling provides a method of interpreting findings at key time points and over time, which may facilitate a better understanding of symptom patterns and lend insight into how HIV symptoms cluster, though this should be studied further in additional patient populations.

Important limitations of this study should be noted. The majority of the study population was male and White, and these findings may not be generalizable to women and patients of non-White race. Further, the inclusion criteria stipulated that all patients have viral loads at baseline that were undetectable on therapy, yielding a highly treatment-adherent population. Thus, study results are more generalizable to a virologically suppressed patient population than a treatment-naïve patient population. There was a significant higher prevalence in the switch group for five HIV-SI items at baseline, suggesting balance was not achieved in randomization. In addition, it is possible that study findings may be confounded by knowledge of treatment assignment. The open-label design may have affected the changes in HIV symptoms found at week 4 between groups; perhaps patients in the no-switch group noticed their symptoms more acutely and those in the switch group were more attuned to symptom improvements. At subsequent visits, these changes were less dramatic. Use of an alternative HRQL measure, rather than the SF-36, designed specifically for the HIV patient population would yield more meaningful HRQL data. Finally, interpretation of the conducted analyses relied on statistical significance, rigid criteria to apply to an exploratory analysis.

5 Conclusion

This study provides evidence that switching virologically suppressed patients to STB from an NNRTI plus FTC/TDF regimen was associated with a decreased prevalence in 11 symptoms as early as 4 weeks after the switch. Enduring benefits at week 48 were observed for nightmare, vivid dreams, weird/intense dreams, dizzy/lightheadedness, fatigue/loss of energy, and pain/numbness in the hands/feet. As people with HIV receiving ART now have life expectancies approaching those without HIV, it is important to identify and take steps to limit those symptoms that interfere with general health and well-being. Future research in real-world clinical settings is needed to better understand how switching to STB may impact symptoms and other PROs.

References

Baran R, Mulcahy F, Krznaric I, Monforte A, Samarina A, Xi H, et al. Reduced HIV symptoms and improved health-related quality of life correlate with better access to care for HIV-1 infected women: the ELLA study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(4 Suppl 3):19616.

Edelman EJ, Gordon K, Justice AC. Patient and provider-reported symptoms in the post-cART era. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):853–61.

Simpson KN, Hanson KA, Harding G, Haider S, Tawadrous M, Khachatryan A, et al. Patient reported outcome instruments used in clinical trials of HIV-infected adults on NNRTI-based therapy: a 10-year review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:164.

Al-Dakkak I, Patel S, McCann E, Gadkari A, Prajapati G, Maiese EM. The impact of specific HIV treatment-related adverse events on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care. 2013;25(4):400–14.

Mannheimer SB, Matts J, Telzak E, Chesney M, Child C, Wu AW, et al. Quality of life in HIV-infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy is related to adherence. AIDS Care. 2005;17(1):10–22.

Safren SA, Biello KB, Smeaton L, Mimiaga MJ, Walawander A, Lama JR, et al. Psychosocial predictors of non-adherence and treatment failure in a large scale multi-national trial of antiretroviral therapy for HIV: data from the ACTG A5175/PEARLS trial. PloS One. 2014;9(8):e104178.

Hogg R, Lima V, Sterne JA, Grabar S, Battegay M, Bonarek M, et al. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):293–9.

Justice AC, Chang CH, Rabeneck L, Zackin R. Clinical importance of provider-reported HIV symptoms compared with patient-report. Med Care. 2001;39(4):397–408.

Gilead Sciences Inc. Stribild (elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) fixed dose combination tablets prescribing information. Foster City: Gilead Sciences Inc; 2014.

Pozniak A, Markowitz M, Mills A, Stellbrink HJ, Antela A, Domingo P, et al. Switching to coformulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir versus continuation of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor with emtricitabine and tenofovir in virologically suppressed adults with HIV (STRATEGY-NNRTI): 48 week results of a randomised, open-label, phase 3b non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(7):590–9.

Bristol-Myers Squibb (2013). SUSTIVA (efavirenz) capsules and tablets for oral use. US prescribing information. http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_sustiva.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2014.

Usach I, Melis V, Peris JE. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors: a review on pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety and tolerability. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:1–14.

Edelman EJ, Gordon K, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Justice AC, Vacs Project T. Patient-reported symptoms on the antiretroviral regimen efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(6):312–9.

Hodder SL, Mounzer K, Dejesus E, Ebrahimi R, Grimm K, Esker S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in virologically suppressed, HIV-1-Infected subjects after switching to a simplified, single-tablet regimen of efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir DF. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(2):87–96.

Justice AC, Freiberg MS, Tracy R, Kuller L, Tate JP, Goetz MB, et al. Does an index composed of clinical data reflect effects of inflammation, coagulation, and monocyte activation on mortality among those aging with HIV? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(7):984–94.

Justice AC, Holmes W, Gifford AL, Rabeneck L, Zackin R, Sinclair G, et al. Development and validation of a self-completed HIV symptom index. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(Suppl 1):S77–90.

Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43(6):1317–25.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305(6846):160–4.

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–401.

Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R, Vagg P, Jacobs G. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

Buscher A, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Giordano TP. Validity of self-report measures in assessing antiretroviral adherence of newly diagnosed, HAART-naive, HIV patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2011;12(5):244–54.

Woodcock A, Bradley C. Validation of the HIV treatment satisfaction questionnaire (HIVTSQ). Qual Life Res. 2001;10(6):517–31.

Woodcock A, Bradley C. Validation of the revised 10-item HIV treatment satisfaction questionnaire status version and new change version. Value Health. 2006;9(5):320–33.

Simpson KN, Chen SY, Wu AW, Boulanger L, Chambers R, Nedrow K, et al. Costs of adverse events among patients with HIV infection treated with nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. HIV Med. 2014;15(8):488–98.

Simpson KN, Hanson KA, Harding G, Haider S, Tawadrous M, Khachatryan A, et al. Review of the impact of NNRTI-based HIV treatment regimens on patient-reported disease burden. AIDS Care. 2014;26(4):466–75.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Mills contributed to the acquisition of the data and manuscript preparation. Dr. Garner contributed to the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation. Dr. Pozniak contributed to the acquisition of the data and manuscript preparation. Dr. Berenguer contributed to the acquisition of the data, and manuscript preparation. Dr. Speck contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and manuscript preparation. Dr. Bender contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and manuscript preparation. Dr. Nguyen contributed to the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation, and is the guarantor of this work.

The authors thank Amy Justice and David Piontkowsky for their critical review of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest and sources of funding

Dr. Mills has received research funding, consulting fees or honorarium, and payment for lectures from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Drs. Garner and Nguyen are employees of Gilead Sciences and hold stock options in the company. Dr. Pozniak has received research funding and consulting fees or honorarium from Gilead Sciences. Dr. Berenguer has received research funding, support for travel, and payment for lectures from Gilead Sciences, and is an employee of the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañon, Madrid, Spain, an institution that received funding from Gilead Sciences for enrolling patients in the clinical trial. Drs. Speck and Bender are employees of Evidera, contract recipients for the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mills, A., Garner, W., Pozniak, A. et al. Patient-Reported Symptoms Over 48 Weeks in a Randomized, Open-Label, Phase IIIb Non-Inferiority Trial of Adults with HIV Switching to Co-Formulated Elvitegravir, Cobicistat, Emtricitabine, and Tenofovir DF versus Continuation of Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor with Emtricitabine and Tenofovir DF. Patient 8, 359–371 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-015-0129-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-015-0129-9