Abstract

Background

Falls and related injuries remain a concern for patient safety in many hospitals and nursing care facilities. In particular, reports examining the relationship between accidents and drugs with a sedative effect have been increasing; however, the analysis of correlation between the background factors of fall accidents and the detailed therapeutic category of drugs is insufficient.

Objectives

Our objective was to estimate fall risk following the administration of hypnotics in inpatients within an acute hospital. We assessed the relationship between falls and hypnotic drugs compared with other medicines.

Study Design and Setting

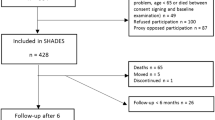

An inpatient population-based study was carried out at Gunma University Hospital, where all inpatients admitted between 1 October and 31 December 2007 were included. Over a 3-month follow-up period, all reports of falling accidents from ward medical staff were investigated.

Results and Discussion

Falls occurred in 1.8 % of males and 1.3 % of females in the study population (n = 3,683). The mean age of patients who experienced falls (64.7 ± 19.5 years) was significantly higher than that of patients who did not (56.2 ± 20.2 years). Multivariate analysis revealed the following drugs as high-risk factors for falling: hypnotics (odds ratio [OR] 2.17, 95 % CI 1.44–3.28), antiepileptics (OR 5.06, 95 % CI 2.70–9.46), opioids (OR 3.91, 95 % CI 2.16–7.10), anti-Alzheimer’s (OR 5.74, 95 % CI 1.62–20.3), anti-Parkinson’s (OR 5.06, 95 % CI 1.58–16.24), antidiabetics (OR 3.08, 95 % CI 1.63–5.84), antihypertensives (OR 2.24, 95 % CI 1.41–3.56), and antiarrhythmics (OR 2.82, 95 % CI 1.36–5.86). Multivariate logistic regression analysis of hypnotics, brotizolam, zopiclone, and estazolam revealed a significant association with an increased risk of inpatient falling accidents, while zolpidem, triazolam, flunitrazepam, and nitrazepam did not.

Conclusion

The present findings suggest that the risk of falling accidents in hospitals differs according to the type of hypnotic drug administered. The appropriate selection of hypnotic drugs, therefore, might be important for reducing the number of patient falls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Injuries due to falls remain a concern for inpatient safety. According to the newest Cochrane database, approximately 30 % of people aged over 65 years living in the community fall each year [1]. Fall incidence in nursing homes is reported to be about three times that in the community, equating to rates of 1.5 falls per bed per year (range 0.2–3.6) [2, 3]. In hospital, on the other hand, an incidence of 3.4 falls per person-year has been reported in geriatric rehabilitation wards, and 6.2 falls per person-year in psychogeriatric wards [4, 5]. In spite of more intense risk management, the high number of accidental falls in hospital is a severe problem.

Several studies have demonstrated that some kinds of medications contribute to falls [1, 2, 4]. Benzodiazepines and hypnotics [6–9], antidepressants [10–12], anti-hypertensives and diuretics [13, 14], narcotics [8], and anti-Parkinson’s [15] drugs are reported as risk factors of falls. We began to investigate the association between accidental falls and medication in wards, and we found that only zolpidem, the ω1-selective non-benzodiazapine, showed the lowest odds ratio (OR) of falls in hypnotics tested.

Hypnotic drugs are frequently used for insomnia (with symptoms such as difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, awaking too early in the morning, and disturbance in sleep quality), and they may cause falls because of their effect on psychomotor activity. Therefore, appropriate selection of hypnotics and assessing the related risks might be important in the prevention of accidental falls. Short-acting non-benzodiazepines are known to be relatively safe hypnotics and are widely used to treat difficulty in falling asleep. In 1999, Rudolph et al. [16] reported that the myorelaxant, motor-impairing, ethanol-potentiating, and anxiolytic-like properties of diazepam were not mediated by α1 gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptors, but might be mediated exclusively by α2, α3, and/or α5 GABAA receptors. In 2008, Hanson et al. [17] reported that in cases of sedative/hypnotic activity of benzodiazapine receptor [BZ (ω)] agonists, determined by the ratio of selectivity in ω1/ω2 receptor subtypes, the difference in ω1/ω2 selectivity may lead to a difference in falling probability. However, the association between falling related to taking hypnotics and the ω1/ω2 selectivity of each hypnotic was not clearly established.

In this study, we assessed the falling frequency of inpatients admitted to a ward of Gunma University Hospital, to clarify the association between the risk of falling and the medication, particularly hypnotics.

2 Methods and Study Design

Gunma University Hospital is a general hospital with 725 beds in 15 medical departments. This study included all hospitalized patients; there were no exclusion criteria regarding disease or age. Medical records were obtained from 3,683 unrelated Japanese hospitalized patients (1,965 males and 1,718 females; mean age 56.5 ± 18.6 years) from October to December 2007 at Gunma University Hospital. Medical record analysis was approved by the Ethical Review Board in Gunma University Hospital. Inpatient falls are regularly registered via incident and accident reports submitted by medical staff. Falls were evaluated according to a previous report by Gibson [18], and medical charts were reviewed to obtain inpatient data. All drugs prescribed for the patients during their stay in hospital were extracted electronically from hospital charts. The frequency of falling was compared among drugs classified as hypnotics, antiepileptics, opioids, anti-Alzheimer’s, anti-Parkinson’s, antipsychotics, antidiabetics, antihypertensives, and antiarrhythmics, according to the therapeutic category of drugs defined by the Japanese Ministry of Health and Labor Welfare.

3 Statistical Methods

The medical staff in the ward (nurses, pharmacists, and medical doctors) who found the fall accident or was informed about one by a patient completed an incident sheet. The data were calculated as the number of patients who experienced one fall divided by the total number of inpatients. The Student’s t test was used for comparison of age, and a chi-square analysis was used for comparison of sex difference. The relationship between medication and the prevalence of falls was estimated by comparing the odds of exposure among patients who fell during hospitalization. A logistic regression analysis with a stepwise procedure was used to identify the independent risk factors of falling as reported by Tanaka et al. [19]. The OR and corresponding 95 % confidence interval (CI) were calculated using logistic regression in StatView (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) software. Finally, a multiple logistic regression analysis, adjusted for use of diuretics and anticoagulants was performed to evaluate the odds of falling for each drug. The full model included age and the use of zolpidem, brotizolam, zopiclone, triazolam, flunitrazepam, nitrazepam, estazolam, antiepileptics, opioids, anti-Alzheimer’s, anti-Parkinson’s, antidiabetics, antihypertensives, and antiarrhythmics. The relationship between OR and ω1/ω2 selectivity reported previously [20–42] was explored using linear regression analysis. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

4 Results

4.1 Characteristics of Patients and Fall Rate

Falling accidents were reported for 116 (3.1 %) of the 3,683 inpatients during hospitalization. Mean age on admission was 56.5 ± 20.2 years. The age of inpatients experiencing a fall (64.7 ± 19.5) was significantly higher (p < 0.001, Student’s t test) than those who did not fall (56.2 ± 20.2). In male patients, the proportion experiencing a fall (67/116, 57.8 %) did not differ from those who did not fall (1,898/3,567 [53.2 %]; p = 0.33, Chi-square test).

4.2 Falling Risk of Medication

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed a significant relationship between risk of inpatient falls and several drug groups, such as hypnotics, antiepileptics, opioids, anti-Alzheimer ’s, anti-Parkinson’s, antidiabetics, antihypertensives, and antiarrhythmics (Table 1). Sex and antipsychotics were not risk factors for falling. In the analysis adjusted for use of diuretics and anticoagulants, brotizolam, zopiclone, and estazolam showed a significant increase in the risk of inpatient falls (p < 0.001, p = 0.011 and 0.013, respectively), while zolpidem, triazolam, flunitrazepam, and nitrazepam did not show any difference (p = 0.315, 0.416, 0.327, and 0.446, respectively) (Table 2).

5 Discussion

Risk factors for falls have been reported [43, 44] to include age, sensorial impairments, various pathologies (e.g., anemia, neoplasms, congestive heart failure, and stroke); environmental and staff conditions; gait instability; limb weakness; urinary incontinence, frequency, or need for assisted toileting; agitation; confusion; impaired judgment; and prescription of high-risk drugs, such as sedative hypnotics. Barbiturates and benzodiazepines promote sleep by binding to and allosterically modulating GABAA receptors in the central nervous system. However, these drugs have been associated with several adverse reactions, including alteration of sleep architecture, nightmares, agitation, confusion, lethargy, withdrawal, and a risk of dependence and abuse. The newest generation of sleep-aid drugs, the non-benzodiazepine hypnotics such as zolpidem, was developed to overcome some of these disadvantages [45].

In this study, only zolpidem, the most ω1/ω2-selective agent, showed an OR of <1 (Table 2). Non-benzodiazepine drugs, including zolpidem, act through a similar neural mechanism as classical benzodiazepines. They bind to the same site on the GABAA receptors but differ significantly in their chemical structure and neuropharmacological profile [46–48]. GABAA receptors have a pentameric form comprising 19 subunits (α1-6, β1-3, γ1-3, δ, ε, θ, π, and ρ1-3) [24, 49, 50]. The benzodiazepine binding site is now known to be associated with α and γ subunits. The pharmacologically defined benzodiazepine receptor subtype BZ1 (ω1) seems to correspond to the GABAA receptors containing α1 subunits, whereas the BZ2 (ω2) subtype is heterogeneous and corresponds to GABAA receptors with α2, α3, or α5 subunits [51, 52]. GABAA receptors containing different α subunits show a heterogenous distribution in the brain, and it has been suggested that different receptor subtypes may have different functional roles [53]. In case of sedative and hypnotic activity of BZ (ω) agonists, determined by the ratio of selectivity in ω1/ω2 receptor subtypes, the difference in ω1/ω2 selectivity may influence the difference in falling probability [17].

Another possible reason for the variance in the risk of falls is the difference in the pharmacokinetics of hypnotics. Zolpidem has the shortest elimination half-life and carries the lowest risk of falling. The maximum plasma concentration of zolpidem is reached 1.5 h after dosing [30]. A shorter time to reach peak concentration and a short elimination half-life may be preferable characteristics for hypnotic agents. A considerable number of accidental falls occur when a patient wakes because of a micturition urge during night. Thus, for patients with insomnia, it is important to select a hypnotic with a short half-life to avoid excessive suppression of psychomotor activity after sleeping.

Finally, low-risk drug–drug interactions could explain the low frequency of falls in patients taking zolpidem. Although the formation of alcohol derivatives of zolpidem is rate-limiting and mediated principally by cytochrome P450 (CYP)3A4 (about 60 %), the rest is metabolized by CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6 [54, 55]. Such metabolic profiles could reduce the risk of drug–drug interaction and genetic polymorphism compared with other hypnotics, such as triazolam, which is metabolised by only CYP3A4 [56, 57]. The difference in metabolic profiles may contribute to the low risk of falling with zolpidem, even when patients are concurrently administered several drugs that inhibit the metabolic pathway of zolpidem. This is especially valid for elderly patients, most of whom receive polytherapy, which increases the risk of drug–drug interaction. Consequently, genetic analysis may be a useful tool for the prevention of falls related to medications, particularly hypnotics.

In this study, we evaluated the association of falling with medication but not the medical conditions or disease of patients. Although we clarified the difference in the risk of falling among hypnotics, in future, we should also establish the relationship between the time when falls occur, drug dosage, and medical condition or disease.

6 Conclusion

Our results show that many falls depend on the type of hypnotic agent in inpatients with insomnia. In order to clarify the correlation between each hypnotic and the risk of falling, it is still necessary to evaluate the time of taking drugs and falling accident. Falls are a common risk for all inpatients. Reduction in the number of falls and related injuries is important for maintaining patient quality of life and for reducing medical costs. However, the risk of falls is not able to be predicted from ω1/ω2 selectivity. The relationship between falling and the profiles of various hypnotics remains to be analyzed.

References

Shuto H, Imakure O, Imakyure O, Matsumoto J, Egawa T, Ying J, Hirakawa M, Kataoka Y, Yanagawa T. Medication use as a risk factor for inpatient falls in an acute care hospital: a case-crossover study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:535–42.

Neutel CI, Perry S, Maxwell C. Medication use and risk of falls. Pharmacoepimemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:97–104.

Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR, Robbins AS. Falls in the nursing home. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:442-51.

Cumming RG. Epidemiology of medication-related falls and fractures in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1998;12:43–53.

Nyberg L, Gustafson Y, Janson A, Sandman PO, Eriksson S. Incidence of falls in three different types of geriatric care. A Swedish prospective study. Scand J Soc Med. 1997;25:8-13.

Ray WA, Griffin MR, Downey W. Benzodiazepines of long and short elimination half-life and the risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 1989;262:3303–7.

Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952–60.

Ensrud KE, Blackwell TL, Mangione CC, Schwartz AV, Hanlon JT, Nevitt MC. Central nervous system-active medications and risk for falls in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1629–37.

Mendelson WB. The use of sedative/hypnotic medication and its correlation with falling down in the hospital. Sleep. 1996;19(9):698–701.

Liu B, Anderson G, Mittman N, To T, Axcell T, Shear N. Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors of tricyclic antidepressants and risk of hip fractures in elderly people. Lancet. 1998;351:1303–7.

Thapa PB, Gideon P, Cost TW, Milam AB, Ray WA. Antidepressants and the risk of falls among nursing home residents. New Engl J Med. 1998;339:875–82.

Luukinen H, Koski K, Laippala P, Kivela SL. Predictors for recurrent falls among the home-dwelling elderly. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1995;13:294–9.

Verhaeverbeke I, Mets I. Drug-induced orthostatic hypotension in the elderly: avoiding its onset. Drug Saf. 1997;17:105–18.

Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. I: psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:30–9.

Bloem BR, Steijns JA, Smits-Engelsman BC. An update on falls. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:15–26.

Rudolph U, Crestani F, Benke D, Brunig I, Benson JA, Fritschy J-M, Martin JR, Bluethmann H, Mohler H. Benzodiazepine actions mediated by specific γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor subtypes. Nature. 1999;401:796–800.

Hanson SM, Morlock EV, Satyshur KA, Czajkowski C. Structural requirements for eszopiclone and zolpidem binding to the gamma-aminobutyric acid type-A (GABA(A)) receptor are different. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7243–52.

Gibson MJ. Falls in later life. In: Improving the health of older people: a world view. Oxford University Press, Oxford; 1990. p. 296–315.

Tanaka M, Suemaru K, Ikegawa Y, Tabuchi N, Araki H. Relationship between the risk of falling and drugs in an academic hospital. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2008;128:1355–61.

Yasui M, Kato A, Kanemasa T, Murata S, Nishitomi K, Koike K, Tai N, Shinohara S, Tokomura M, Horiuchi M, Abe K. Pharmacological profiles of benzodiazepinergic hypnotics and correlations with receptor subtypes. Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2005;25:143–51.

Pascal GG, Shirakawa K. Zolpidem: objectives, strategy and medicinal chemistry. Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;4:93–7.

Shirakawa K. Pharmacological profile and clinical effect of zolpidem (Myslee tablets), a hypnotic agent. Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2002;119:111–8.

Noguchi H, Kitazumi K, Mori M, Shiba T. Binding and neuropharmacological profile of zaleplon, a novel nonbenzodiazepine sedative/hypnotic. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;434:21–8.

Hadingham KL, Wingrove P, Le Bourdelles B, Palmer KJ, Ragan CI, Whiting PJ. Cloning of cDNA sequences encoding human alpha 2 and alpha 3 gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor subunits and characterization of the benzodiazepine pharmacology of recombinant alpha 1-, alpha 2-, alpha 3-, and alpha 5-containing human gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;43:970–5.

Watanabe Y, Shibuya T, Khatami S, Salafsky B. Comparison of typical and atypical benzodiazepines on the central and peripheral benzodiazepine receptors. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1986;42:189–97.

Greenblatt DJ, Harmatz JS, von Moltke LL, Wright CE, Durol AL, Harrel-Joseph LM, Shader RI. Comparative kinetics and response to the benzodiazepine agonists triazolam and zolpidem: evaluation of sex-dependent differences. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:435–43.

Greenblatt DJ, Harmatz JS, von Moltke LL, Ehrenberg BL, Harrel L, Corbett K, Counihan M, Graf JA, Darwish M, Mertzanis P, Martin PT, Cevallos WH, Shader RI. Comparative kinetics and dynamics of zaleplon, zolpidem, and placebo. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:553–61.

Gustavson LE, Carrigan PJ. The clinical pharmacokinetics of single doses of estazolam. Am J Med. 1990;88:2S–5S.

Saari TI, Laine K, Leino K, Valtonen M, Neuvonen PJ, Olkkola KT. Effect of voriconazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zolpidem in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:116–20.

Olubodun JO, Ochs HR, von Moltke LL, Roubenoff R, Hesse LM, Harmatz JS, Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ. Pharmacokinetic properties of zolpidem in elderly and young adults: possible modulation by testosterone in men. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;56:297–304.

Tornio A, Neuvonen PJ, Backman JT. The CYP2C8 inhibitor gemfibrozil does not increase the plasma concentrations of zopiclone. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:645–51.

Nakajima T, Takazawa S, Hayashida S, Nakagome K, Sasaki T, Kanno O. Effects of zolpidem and zopiclone on cognitive and attentional function in young healthy volunteers: an event-related potential study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54:37–40.

Villikka K, Kivistö KT, Lamberg TS, Kantola T, Neuvonen PJ. Concentrations and effects of zopiclone are greatly reduced by rifampicin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43:471–4.

Tokairin T, Fukasawa T, Yasui-Furukori N, Aoshima T, Suzuki A, Inoue Y, Tateishi T, Otani K. Inhibition of the metabolism of brotizolam by erythromycin in humans: in vivo evidence for the involvement of CYP3A4 in brotizolam metabolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:172–5.

Osanai T, Ohkubo T, Yasui N, Kondo T, Kaneko S. Effect of itraconazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a single oral dose of brotizolam. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58:476–81.

van Gerven JM, Uchida E, Uchida N, Pieters MS, Meinders AJ, Schoemaker RC, Nanhekhan LV, Kroon JM, de Visser SJ, Altorf B, Yasuda K, Yasuhara H, Cohen AF. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of a single oral dose of nitrazepam in healthy volunteers: an interethnic comparative study between Japanese and European volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;38:1129–36.

Abernethy DR, Greenblatt DJ, Locniskar A, Ochs HR, Harmatz JS, Shader RI. Obesity effects on nitrazepam disposition. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1986;22:551–7.

Greenblatt DJ, Abernethy DR, Locniskar A, Ochs HR, Harmatz JS, Shader RI. Age, sex, and nitrazepam kinetics: relation to antipyrine disposition. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985;38:697–703.

Sugimoto K, Araki N, Ohmori M, Harada K, Cui Y, Tsuruoka S, Kawaguchi A, Fujimura A. Interaction between grapefruit juice and hypnotic drugs: comparison of triazolam and quazepam. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:209–15.

Otani K, Yasui N, Furukori H, Kaneko S, Tasaki H, Ohkubo T, Nagasaki T, Sugawara K, Hayashi K. Relationship between single oral dose pharmacokinetics of alprazolam and triazolam. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;12:153–7.

Aoshima T, Fukasawa T, Otsuji Y, Okuyama N, Gerstenberg G, Miura M, Ohkubo T, Sugawara K, Otani K. Effects of the CYP2C19 genotype and cigarette smoking on the single oral dose pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of estazolam. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:535–8.

Mancinelli A, Guiso G, Garattini S, Urso R, Caccia S. Kinetic and pharmacological studies on estazolam in mice and man. Xenobiotica. 1985;15:257–65.

Evans D, Hodgkinson B, Lambert L, Wood J. Falls risk factors in the hospital setting: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Pract. 2001;7:38–45.

Oliver D, Connelly JB, Victor CR, Shaw FE, Whitehead A, Genc Y, Vanoli A, Martin FC, Gosney MA. Strategies to prevent falls and fractures in hospitals and care homes and effect of cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2007;334:82–8.

Ramakrishnan K, Scheid DC. Treatment options for insomnia. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:517–26.

Shirakawa K. Pharmacological profile and clinical effect of zolpidem (Myslee tablets), a hypnotic agent. Folia Pharmacol Jpn. 2002;119:111–8.

Darcourt G, Pringuey D, Salliere D, Lavoisy J. The safety and tolerability of zolpidem—an update. J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13:81–93.

Scharf MB, Roth T, Vogel GW, Walsh JK. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study evaluating zolpidem in the treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:192–9.

Olsen RW, Sieghart W. International Union of Pharmacology. LXX. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors: classification on the basis of subunit composition, pharmacology, and function. Update. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;60:243–60.

Sieghart W. Structure and pharmacology of gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptor subtypes. Pharmacol Rev. 1995;47:181–234.

Pritchett DB, Lüddens H, Seeburg PH. Type I and Type II GABAA-benzodiazepine receptors produced in transfected cells. Science. 1989;245:1389–92.

Pritchett DB, Seeburg PH. γ-Aminobutyric acidA receptor α5-subunit creates novel type II benzodiazepine receptor pharmacology. J Neurochem. 1990;54:1802–4.

Sanger DJ, Benavides J, Perrault G, Morel E, Cohen E, Joly D, Zivkovic B. Recent developments in the behavioral pharmacology of benzodiazepine (v) receptors: evidence for the functional significance of receptors subtypes. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1994;18:335–72.

Pichard L, Gillet G, Bonfils C, Domergue J, Thénot JP, Maurel P. Oxidative metabolism of zolpidem by human liver cytochrome P450S. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:1253–62.

von Moltke LL, Weemhoff JL, Perloff MD, Hesse LM, Harmatz JS, Roth-Schechter BF, Greenblatt DJ. Effect of zolpidem on human cytochrome P450 activity, and on transport mediated by P-glycoprotein. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2002;23:361–7.

Miyazaki M, Nakamura K, Fujita Y, Guengerich FP, Horiuchi R, Yamamoto K. Defective activity of recombinant cytochromes P450 3A4.2 and 3A4.16 in oxidation of midazolam, nifedipine, and testosterone. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:2287–91.

Holm KJ, Goa KL. Zolpidem: an update of its pharmacology, therapeutic efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of insomnia. Drugs. 2000;59:865–89.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Aiko Matsumoto for her secretarial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Obayashi, K., Araki, T., Nakamura, K. et al. Risk of Falling and Hypnotic Drugs: Retrospective Study of Inpatients. Drugs R D 13, 159–164 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-013-0019-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-013-0019-3