Abstract

Background

The medication reconciliation (MedRec) process conducted at hospital admission uses either a proactive or retroactive model. Many hospitals have experienced challenges with MedRec, particularly its proactive model.

Objective

The aim of this study was to analyze and quantify the retroactive and proactive MedRec models.

Settings

The study was conducted at Campbellton Regional Hospital, a member of Vitalité Health Network in Canada.

Method

This prospective, observational study was conducted at Regional Hospital over a 3-month period. All patients undergoing MedRec during this time were included.

Main Outcome Measure

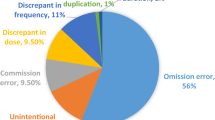

The primary endpoint was to compare the time components of the process for the two models, while the secondary endpoint was to determine the types of intentional and unintentional medication discrepancies.

Results

After 249 MedRecs had been reviewed, 180 patients were enrolled. The total number of medications reconciled was 2118. Of the 180 patients, 84 (46%) were evaluated using the proactive model. The median time from admission to the MedRec process was significantly shorter for the proactive model (48 min) than the retroactive model (1135 min) [p < 0.001]. The percentage of documented intentional medication modifications in the proactive model (16.3%) was more than twice that in the retroactive model (7.3%) [p < 0.001]. Patients evaluated by the proactive model had a significantly shorter hospital stay than those evaluated by the retroactive model (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that implementation of the proactive model was feasible. Compared with the retroactive model, the proactive model had a positive impact on preventing discrepancies with timeliness and efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, et al. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1842–7.

Tam VC, Knowles SR, Cornish PL, Fine N, et al. Frequency, type and clinical importance of medication history errors at admission to hospital: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2005;173:510–5.

Tamblyn R, et al. Effect of an electronic medication reconciliation intervention on adverse drug events: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1910756.

Accreditation Canada. Required Organizational Practices, 2017 Handbook, Version 2. Available at: https://www3.accreditation.ca/OrgPortal/Documents/Resources/AddResources/ROPHandbook_2017_v2_EN.pdf. Accessed 07/10/19

Lo L, Kwan J, Fernandes OA, et al. Chapter 25. Medication Reconciliation Supported by Clinical Pharmacists (NEW). En: Making Health Care Safer II: An Updated Critical Analysis of the Evidence for Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 211. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2013 (Consultado 9 Julio 2015). Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK133408/

American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on the pharmacist’s role in medication reconciliation. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:453–6.

Nester TM, Hale LS. Effectiveness of a pharmacist-acquired medication history in promoting patient safety. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59:2221–5.

Lizer MH, Brackbill ML. Medication history reconciliation by pharmacists in an inpatient behavioral health unit. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1087–91.

Gleason KM, Brake H, Agramonte V, et al. Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) Toolkit for Medication Reconciliation. (Prepared by the Island Peer Review Organization, Inc., under Contract No. HHSA2902009000 13C.) AHRQ Publication No. 11(12)-0059. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Revised August 2012.

Reeder TA, Mutnick A. Pharmacist- versus physician obtained medication histories. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:857–60.

Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:424–9.

Gleason KM, Groszek JM, Sullivan C, et al. Reconciliation of discrepancies in medication histories and admission orders of newly hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:1689–95.

Johnston R, Saulnier L, Gould O. Best possible medication history in the emergency department: comparing pharmacy technicians and pharmacists. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2010;63:359–65.

Leung M, Jung J, Lau W, Jung B, et al. Best possible medication history for hemodialysis patients obtained by a pharmacy technician. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62:386–91.

Leguelinel-Blache G, Arnaud F, Bouvet S, et al. Impact of admission medication reconciliation performed by clinical pharmacists on medication safety. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(9):808–14.

Kalb K, Shalansky S, Legal M, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies associated with reliance on prescription databases for medication reconciliation on admission to a general medical ward. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(4):284–9.

Rey MBC, Prados YA, Gómez ES. Analysis of the medication reconciliation process conducted at hospital admission. Farm Hosp. 2016;40(4):246–59.

Kraus SK, Sen S, Murphy M, et al. Impact of a pharmacy technician-centered medication reconciliation program on medication discrepancies and implementation of recommendations. Pharm Pract. 2017;15(2):901.

Digiantonio N, Lund J, Bastow S. Impact of a pharmacy-led medication reconciliation program. P&T. 2018;43(2):105–10.

Remtulla S, Brown G, Frighetto L. Best possible medication history by a pharmacy technician at a tertiary care hospital. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(5):402–5.

Meguerditchian AN, Krotneva S, Reidel K, et al. Medication reconciliation at admission and discharge: a time and motion study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:485.

Mazhar F, Akram S, Al-Osaimi YA, et al. Medication reconciliation errors in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia: admission discrepancies and risk factors. Pharm Pract. 2017;15(1):864.

Kneza L, Suskovica S, Rezonjab R, et al. The need for medication reconciliation: a cross-sectional observational study in adult patients. Respir Med. 2011;105(Suppl 1):S60–6.

Sund JK, Sletvold O, Mellingsæter TC, et al. Discrepancies in drug histories at admission to gastrointestinal surgery, internal medicine and geriatric hospital wards in Central Norway: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013427.

Baek H, Cho M, Kim S, Hwang H, Song M, Yoo S. Analysis of length of hospital stay using electronic health records: a statistical and data mining approach. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195901.

Suzuki H, Perencevich EN, Nair R, Livorsi DJ, Goto M. Excess length of acute inpatient stay attributable to acquisition of hospital-onset gram-negative bloodstream infection with and without antibiotic resistance: a multistate model analysis. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9(2):96.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians for their efforts and contributions in establishing this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding was provided for this research.

Conflict of interest

Tania Levesque, Hani Abdelaziz, Alyson Smith, Nancy Cormier, Maryse Bernard, Michèle Laplante and Josee Gagnon declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Board.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

TL contributed to the project idea, study conception, analysis of data discrepancy and manuscript review. HA contributed to study conception and design and data and statistical analysis, and drafted and reviewed the manuscript. AS was involved in data collection and edited and reviewed the manuscript. NC, MB and ML were involved in analysis of data discrepancy and manuscript review. JG contributed to the project idea, study conception and manuscript review. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved submission of this draft for publication.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levesque, T., Abdelaziz, H., Smith, A. et al. Medication Reconciliation at Hospital Admission: Proactive Versus Retroactive Models. Drugs Ther Perspect 37, 545–551 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-021-00872-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-021-00872-9