Abstract

Introduction

Globally, the rate of opioid prescription is high for chronic musculoskeletal conditions despite guidelines recommending against their use as their adverse effects outweigh their modest benefit. Deprescribing opioids is a complex process that can be hindered by multiple prescriber- and patient-related barriers. These include fear of the process of, or outcomes from, weaning medications, or a lack of ongoing support. Thus, involving patients, their carers, and healthcare professionals (HCPs) in the development of consumer materials that can educate and provide support for patients and HCPs over the deprescribing process is critical to ensure that the resources have high readability, usability, and acceptability to the population of interest.

Objective

This study aimed to (1) develop two educational consumer leaflets to support opioid tapering in older people with low back pain (LBP) and hip or knee osteoarthritis (HoKOA), and (2) evaluate the perceived usability, acceptability, and credibility of the consumer leaflets from the perspective of consumers and HCPs.

Design

This was an observational survey involving a consumer review panel and an HCP review panel.

Participants

30 consumers (and/or their carers) and 20 HCPs were included in the study. Consumers were people older than 65 years of age who were currently experiencing LBP or HoKOA, and with no HCP background. Carers were people who provided unpaid care, support, or assistance to an individual meeting the inclusion criteria for consumers. HCPs included physiotherapists (n = 9), pharmacists (n = 7), an orthopaedic surgeon (n = 1), a rheumatologist (n = 1), nurse practitioner (n = 1) and a general practitioner (n = 1), all with at least three years of clinical experience and who reported working closely with this target patient population within the last 12 months.

Methods

Prototypes of two educational consumer leaflets (a brochure and a personal plan) were developed by a team of LBP, OA, and geriatric pharmacotherapy researchers and clinicians. The leaflet prototypes were evaluated by two separate chronological review panels involving (1) consumers and/or their carers, and (2) HCPs. Data collection for both panels occurred via an online survey. Outcomes were the perceived usability, acceptability, and credibility of the consumer leaflets. Feedback received from the consumer panel was used to refine the leaflets, before circulating the leaflets for further review by the HCP panel. Additional feedback from the HCP review panel was then used to refine the final versions of the consumer leaflets.

Results

Both consumers and HCPs perceived the leaflets and personal plan to be usable, acceptable, and credible. Consumers rated the brochure against several categories, which scored between 53 and 97% positive responses. Similarly, the overall feedback provided by HCPs was 85–100% positive. The modified System Usability Scale scores obtained from HCPs was 55–95% positive, indicating excellent usability. Feedback for the personal plan from both HCPs and consumers was largely positive, with consumers providing the highest positive ratings (80–93%). While feedback for HCPs was also high, we did identify that prescribers were hesitant to provide the plan to patients frequently (no positive responses).

Conclusions

This study led to the development of a leaflet and personal plan to support the reduction of opioid use in older people with LBP or HoKOA. The development of the consumer leaflets incorporated feedback provided by HCPs and consumers to maximise clinical effectiveness and future intervention implementation.

Plain Language Summary

Opioids are medications that are often used to treat severe or chronic pain. However, they can have serious adverse effects and are not usually recommended for long-term use. This study aimed to create educational materials for patients with chronic low back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis who are taking opioids and to evaluate the materials’ perceived usability, acceptability, and credibility from the perspective of both healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients. The materials included a brochure and a personal plan and were developed by a team of researchers and clinicians. Both materials were evaluated by HCPs and patients in separate review panels. The brochure and personal plan were found to be usable, acceptable, and credible by both groups. The materials were created to support patients in reducing their opioid use and were refined based on feedback from both HCPs and patients. The materials may be useful in supporting the complex process of tapering off opioids, which can be hindered by various barriers related to both patients and HCPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

To maximise clinical effectiveness and future implementation, feedback from healthcare professionals (HCPs) and consumers was utilised in the development of information leaflets to support opioid tapering. |

Consumers and HCPs found the information leaflets to be a highly usable, acceptable, and credible resource for opioid tapering. |

1 Introduction

Globally, the rate of opioid prescription is high for chronic musculoskeletal conditions. A recent systematic review of observational studies, including cross-sectional, cohort, and case–control studies from North America, UK, Australia and Spain, found that 41.5% of people with chronic low back pain (LBP) are prescribed opioids [1]. In Australia alone, over 25% of opioid prescriptions are administered for LBP, with osteoarthritis (OA) accounting for another 10% of prescriptions [2]. Alarmingly, the rate of opioid prescriptions continues to increase dramatically for musculoskeletal conditions [3], despite the absence of strong support for its efficacy. Evidence shows that opioids have limited use in patients with LBP [4, 5] and only a small to moderate effect for hip or knee osteoarthritis (HoKOA) [5, 6], with most guidelines recommending against them because the adverse effects outweigh the modest benefit. Nonetheless, opioids continue to be prescribed and used frequently for managing these conditions.

The safety of opioid use has attracted growing scrutiny due to a substantial rise in opioid-related harm and hospitalisations for accidental poisoning or deaths [7]. Long-term opioid use, defined as ongoing use for more than three months, and misuse of opioids can lead to important adverse drug reactions, substance abuse disorders, cardiovascular events, fractures, and death [8]. Insurance data from the United States suggest that more than half of patients who take opioids for at least three months continue to take them for years [9], leading to significantly higher rates of addiction, accidental overdose and death [9, 10]. The same study found that one in three long-term users will present to an Emergency Department (ED) every year [10]. Between 2007 and 2016, Australia has seen a 25% increase in hospitalisations and ED presentations due to opioid poisoning [11]. This results in substantial costs to society from excess medical care for opioid abuse and loss of productivity (i.e. reduced productive time or increased disability) [12]. Older people are more vulnerable to commonly reported adverse events and harms associated with opioid use, including sedation, dizziness, and respiratory suppression [13], as well as falls [14].

Polypharmacy, which describes the concurrent use of multiple medications, is common in older patients and can lead to drug–drug and drug–disease interactions [15], geriatric syndromes such as confusion, and injurious falls. In addition, age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics can increase an older patient’s risk of drug accumulation and susceptibility to adverse drug effects [15, 16]. However, for older patients who need to or wish to reduce opioid use, deprescribing (tapering) can often be challenging due to limited access to age-appropriate, non-pharmacological pain management strategies. Moreover, very few approaches have been successfully developed and evaluated to target this clinical group.

Deprescribing medications is a complex process that can be hindered by multiple prescribers and patient-related barriers [17,18,19]. For example, patients expressing fear of the process or outcomes from weaning of medications is common [19], which can subsequently impact heavily on a general practitioner’s decision to deprescribe [7]. In addition, prescribers in primary care have been shown to have reduced self-efficacy to develop and monitor opioid deprescribing plans for older adults [20]. However, qualitative studies have been conducted to better understand the enablers and barriers for tapering medications, and advocate that shared decision making is important to ensure deprescribing success [21, 22]. For shared decision making to occur effectively, patients must be fully informed about the potential benefits and harms of treatment options, and have the opportunity to express their personal preferences about treatment choices [23].

Increasing awareness of engaging patients in the shared decision-making process for deprescribing has led to the development of consumer resources. Studies have shown that consumer resources can be used effectively as self-directed education tools to support deprescribing of high-risk medications. For example, the Canadian EMPOWER trial, which involved older community-dwelling long-term benzodiazepine users, a drug commonly used to treat anxiety and insomnia, found that 62% of participants who received educational leaflets initiated discussions about deprescribing with their healthcare provider [24]. In fact, one in four participants proceeded to successfully discontinue their benzodiazepine use within 6 months [24]. Similarly, another benzodiazepine deprescribing study in Australia utilised consumer resources and achieved a sustained 19% reduction in benzodiazepine use over 2 years [25]. As such, consumer leaflets can be used as powerful tools to facilitate effective, shared decision making and successful deprescribing of medications.

However, while patient involvement in the co-production of consumer resources appears intuitive and is actively promoted in health research [26, 27], it is not commonly practiced. Furthermore, healthcare professionals (HCPs), who play an influential role in whether older people choose to have their medications deprescribed [21, 22], are not regularly engaged in developing consumer resources. Involving patients, their carers, and HCPs in the development of consumer materials is highly beneficial and ensures that the resources have high readability, usability, and acceptability to the population of interest. As shown by the two benzodiazepine deprescribing studies discussed above, the involvement of various stakeholders in the development of a deprescribing intervention is critical to its success. The EMPOWER educational brochure was validated by experts in geriatric pharmacy, while Dollman et al. developed the booklets in consultation with consumers and their carers, general practitioners (GPs), community pharmacists, staff of aged care facilities, and other health professionals [25].

Despite the availability of resources and guidelines for clinicians to assist with opioid tapering, few have been developed specifically for older adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain who are taking opioids long-term. This population has unique challenges and non-pharmacological treatment options compared with patients taking long-term opioids for other indications. To date, no patient-focused opioid tapering materials, such as leaflets or brochures, have been evaluated for effectiveness. While web-based or video-based interventions have been tested, many older adults may not have the necessary technological expertise and may prefer a hard-copy resource. The EMPOWER leaflets, which have been shown to be an effective intervention for benzodiazepine deprescription, may not be fully applicable to the older adult with chronic musculoskeletal pain seeking to taper off their opioid medication. Therefore, there is a need for the development of an educational leaflet specifically addressing opioid tapering for this population.

Thus, the aims of this study were to (1) develop consumer leaflets to support the reduction of opioid use in older people with LBP or HoKOA, and (2) evaluate the perceived usability, acceptability, and credibility of the consumer leaflets from the perspective of consumers and HCPs.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

The Development of Consumer Information Leaflets to Support Tapering of Opioids in Older Adults with Low Back Pain and Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis (TANGO) study was an observational survey study. The study involved developing and evaluating two consumer leaflets (a brochure and a personal plan) targeting a reduction in opioid use in older people with LBP, hip OA, or knee OA. Prototypes of the consumer leaflets were developed by a team of LBP and OA researchers and clinicians with expertise in clinical pharmacology, pharmacy, rheumatology, physiotherapy, and user testing methods for consumer medicines information. The leaflet prototypes were evaluated by two separate consecutive review panels involving (1) consumers and/or their carers, and (2) HCPs. Data collection for both panels occurred via online surveys. Outcomes were the perceived usability, acceptability, and credibility of the consumer leaflets. Feedback from the consumer review panel was used to refine the leaflet before it was circulated to the HCP review panel. Additional feedback from the HCP review panel was used to refine the final versions of the consumer leaflets, which will be evaluated in a future randomised control trial.

2.2 Initial Development of the Consumer Leaflets

2.2.1 Conception and Content Development of the Consumer Leaflets

The concept of the two consumer leaflets—the brochure and the personal plan—were developed by a team of LBP and OA researchers and clinicians with expertise in clinical pharmacology, pharmacy, rheumatology, and physiotherapy. The target audience for the two consumer leaflets was older people with LBP or HoKOA who use opioids and are willing to consider reducing use of the medication.

The brochure was designed to empower consumers to engage in the process of reducing their opioid use and to facilitate shared decision making with their treating health professionals. The brochure aimed to provide readers with information about tapering opioids under the following headings.

-

(1)

What is chronic musculoskeletal pain?

-

(2)

What are opioids?

-

(3)

Why should I reduce or stop my opioid?

-

(4)

What side effects can I experience while taking opioids?

-

(5)

How do I stop taking my opioid?

-

(6)

What should I watch for when coming off my opioid?

-

(7)

What non-drug options can I do to manage my pain?

-

(8)

What should I do if I continue to feel worse?

-

(9)

Who do I contact to reduce or stop my opioid?

The topics were included based on previous studies where information leaflets were developed to support patients during deprescribing of antipsychotics, benzodiazepines/Z-drugs and proton pump inhibitors [24, 28, 29].

Complementary to the brochure, a separate personal plan leaflet was developed to support patients wishing to seek assistance with opioid tapering from their general practitioner, based on findings from our previous study on the development of consumer resources to support deprescribing decisions [29]. To facilitate dose reduction, the personal plan was designed to allow general practitioners to document 2 weeks of tailored date- and time-specific medication dosages for patients to follow. A weblink and Quick Response (QR) code was added to the personal plan at the end of the two rounds of reviews to allow for convenient reprinting of additional blank copies when extension of the dose-reduction period was necessitated. In addition, to support patients with self-monitoring their dose-reduction, the personal plan was designed to track self-reported adherence to prescribed dosages and adverse effects experienced during the weaning process. It was anticipated that patients could then discuss their self-reported adherence and adverse effects with their general practitioner upon clinical review, promoting shared decision making. To demonstrate the complementary nature of the brochure and personal plan leaflets, a 1-week excerpt of the personal plan with an example included was inserted into the final page of the brochure.

2.2.2 Prototyping the Consumer Leaflets

After conception and content development by the research team, prototypes of the leaflets were developed by a researcher (NJ) experienced in developing consumer deprescribing resources and user testing methods for consumer medicines information. The brochure comprised seven pages in addition to a one-page personal plan. Representatives from Musculoskeletal Australia, a national consumer organisation advocating for people with musculoskeletal conditions, provided informal preliminary feedback on the leaflet prototypes. The leaflet prototypes were then reviewed in two separate consecutive review panels involving (1) consumers (or their carers) and (2) HCPs.

2.3 Participants

Consumers were people aged over 65 years who were currently experiencing self-reported pain associated with LBP, hip OA, or knee OA, were fluent in English, and had current internet access. Although it was not mandatory that participants were current opioid users, to be included participants needed to have had a past history of opioid use. This population was chosen to ensure the brochure would contain information relevant to participants with a lived experience of musculoskeletal pain. We excluded participants with a health professional background, inadequate levels of English to understand the consumer leaflets and complete the outcome measures, or inadequate cognitive capacity to provide informed consent. Carers were people who provided unpaid care, assistance, or support to a family member or friend who met the inclusion criteria for consumers. We excluded professional and paid carers from the consumer review panel.

HCPs were eligible if they had at least three years of clinical experience and reported working closely with older patients experiencing LBP, hip OA, or knee OA within the past 12 months. This included, but was not limited to, general practitioners, pain management physicians, rheumatologists, geriatricians, orthopaedic surgeons, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and nurse practitioners.

2.4 Recruitment

2.4.1 Consumers Review Panel

Potential consumers (and/or their unpaid carers) were recruited from the general community (e.g., via poster advertisements, social media) and consumer groups (e.g., Musculoskeletal Australia). Thirty consumers and/or carers were determined to be sufficient for this study. There was no prespecified sample size for either subgroup. Interested potential participants were invited to complete a brief online prescreening questionnaire to determine their suitability for the study. After reviewing the participant information sheet, eligible participants were invited to sign the online consent form.

2.4.2 Health Professionals Review Panel

Investigators identified HCPs working in a variety of settings from their professional networks across Australia. Twenty HCPs were deemed sufficient for this study to represent a diverse group of clinicians who often see patients with musculoskeletal conditions, such as general practitioners, rheumatologists, pharmacists, and physiotherapists. After collecting and analysing data it was found that theme saturation was reached for non-prescribers. However, theme saturation was not achieved for prescribers, as only three of them consented to participate in this study. This was despite efforts to increase the sample size of prescribers through various recruitment methods, including convenience sampling from the authors’ professional networks, snowball sampling, and advertising in professional organisation newsletters. The research team phoned or emailed potential HCP review panel participants to introduce the study. Interested and eligible HCPs were provided with the study documents. Those agreeable to participating in the study were asked to sign the online consent form.

2.5 Data Collection and Procedures

The initial design of the data collection process was based on prior consumer user testing methods conducted by Jokanovic et al. [29]. However, the user testing and semi-structured interview data collection method was adapted and modified to an online survey as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic prevented face-to-face research activity in Australia.

2.5.1 Consumer Review Panel

After providing consent, participants in the consumer review panel were emailed a link to the online feedback survey and an electronic copy of the leaflets. Participants included in this panel were asked to provide information about their demographic characteristics, level of education, medical history, and medication use. Carers were asked to provide information on the medical history and medication use of the person for whom they provided care. Self-reported health literacy was measured using three validated questions on a 5-item Likert scale to determine independence with reading health information, confidence with completing medical forms, and ease of understanding written medical information [30]. Participants were then asked to provide feedback on the brochure and personal plan in two separate sections.

In Sect. 1, participants were asked 13 questions to provide feedback on the overall design, content, acceptability, perceived credibility, and perceived usefulness on a 5-item scale of all pages of the brochure. They were also asked to indicate their emotional response (feeling) elicited by reading the brochure, on a 5-item scale (strongly negative–strongly positive), of all pages of the brochure. Participants were then allocated two random pages of the brochure and asked five questions for additional specific feedback on each page using a 5-item Likert scale (strongly disagree–strongly agree). An open-ended question was included to allow participants to provide additional unrestricted feedback for each randomly allocated page if they wished. In Sect. 2, participants were asked four questions to provide feedback on the categories of acceptability, readability, and perceived usefulness of the personal plan leaflet using the same 5-item Likert scale. An open-ended question was also included in this section to allow participants of the consumer panel to provide specific recommendations for improvement if they wished.

2.5.2 Healthcare Professional Review Panel

After providing consent, participants in the HCPs’ review panel were emailed a link to the online feedback survey and an electronic copy of the leaflets. Participants included in this panel were asked to provide information about their profession (e.g., general practitioner, pain physician), and capacity to prescribe medications. Like the consumer review panel, participants in the HCP review panel were asked to provide feedback on the brochure and personal plan in two separate sections. For both sections, participants were presented with a series of statements and were asked to rate their level of agreement with each statement on a 5-item Likert scale (strongly agree–strongly disagree).

In Sect. 1, participants were presented with four statements related to the content (readability, adequacy, relevance) on all pages of the brochure excluding the personal plan. The HCPs were also invited to provide any additional recommendations for improvement via an open-ended question. Participants in the HCP review panel were asked to complete an additional modified System Usability Scale (mSUS) questionnaire regarding the brochure. The validated System Usability Scale (SUS) consists of 10 questions scored on a 5-item Likert scale (strongly agree–strongly disagree) to assess the perceived usability of a product or tool [31]. However, to elicit perspectives specifically related to the perceived usefulness of the brochure, the original SUS questions were modified where two questions were removed and one question, “this brochure would be useful for patients who would like to reduce their opioids”, was added to form the mSUS.

In Sect. 2, participants were asked to provide feedback on the perceived usability of the personal plan, with questions tailored towards the participant’s capacity to prescribe medications. Prescribers were asked six questions while non-prescribers were asked four questions regarding the personal plan in this section.

2.6 Consumer and Healthcare Professional Analysis

Prespecified cut-offs were agreed upon by the research team to determine when brochure pages required refinement to incorporate the feedback provided. To determine a score that could be used to then identify a cut-off, the Likert scale was converted into values from 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). The mean of the total scores was then calculated to derive a mean sum score (presented in electronic supplementary material [ESM] A). For the consumer panel, any page within the main brochure that received a summed score of < 20 points (of a possible 25) and a score of < 16 points (of a possible 20) for the personal plan leaflet required refinement. For the HCP panel, refinements were made to the brochure if the overall feedback provided by a participant had a summed score of < 16 points (of a possible 20), and a score of < 24 for prescribers (of a possible 30) and 16 points for non-prescribers (of a possible 20) for the personal plan.

For ease of interpretation of the Likert scores, the percentage of results from strongly agree to strongly disagree was calculated. The percentage of positive responses, defined as answers scoring above 3 (agree and strongly agree) on the 5-item Likert scale, were also calculated for each question.

2.6.1 Modified System Usability Scale Calculation

As the SUS was modified for this study, the data analysed also had to be modified from the original methodology [31]. Instead, the mSUS scores were presented as the percentage of results and percentage of positive responses.

Furthermore, in order to ensure that the brochure complied with the recommended grade 8 (12–14 years of age, with 8 years of Australian education) readability level for health information, the Flesch–Kincaid grade level assessment was used after the final modifications to the brochure were completed [32,33,34].

2.7 Refinement of Consumer Leaflets

Refinement of consumer leaflets occurred on two occasions—after completion of the consumer review panel and after completion of the HCP review panel to produce the final brochure and personal plan. The investigators discussed any disagreements with the comments provided by consumers or HCPs in order to reach a consensus.

3 Results

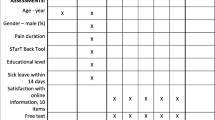

Participant characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Approximately half of the consumers were female (57%), and 90% (n = 27) of participants reported a current episode of LBP, with 47% (n = 14) also experiencing comorbid HoKOA. The majority of consumers reported a history of opioid use (67%), with 43% (n = 13) currently consuming opioids and nearly one-third using opioids regularly (n = 9). Most of the consumers had high self-reported health literacy {reading health information (median, interquartile range [IQR]) = 1, 0; filling medical forms (median [IQR]) = 1, 0; understanding written medical information (median [IQR]) = 1, 0}. Of 20 HCPs, 45% (n = 9) were physiotherapists and 35% were pharmacists (n = 7), and one each of orthopaedic surgeon, rheumatologist, nurse practitioner and general practitioner. Three (15%) of the 20 HCPs were prescribers. Two prescribers reported that they commonly treated patients with LBP or HoKOA with opioids.

3.1 Consumer Review Panel

Most consumers rated the pre-consumer feedback brochure and personal plan (ESM B) positively across all categories, in particular the design and content categories, as shown in Table 2.

When asked to provide specific feedback for each page, consumers provided suggestions on layout and advice to amend words or modify sentences to aid readability and understanding. Many also shared their perspectives on the brochure relating to the advice provided to their first-hand experiences with pain, opioid use, and advice from health professionals.

The personal plan was perceived positively by the majority of the consumers (percentage of positive responses = 80–93%) across all questions relating to acceptability, readability, and perceived usefulness.

It was established a priori that any page receiving a summed score of < 20 points (ESM C) by any panel member would be amended and improved according to the feedback; however, upon data analysis, it was found that not all participants who scored below the threshold provided useful feedback. For example, one of the participants whose scores fell below the threshold for page 2 only stated “no comments”. On the other hand, many participants whose scores were above 20 also provided meaningful and constructive feedback. After deliberation among the authors, it was decided that all useful feedback provided regardless of sum scores would be implemented for both the brochure and personal plan.

Consumers provided feedback that the following aspects of the leaflet should be improved: the illustrations were too ‘child-like’, not enough emphasis that opioids are only for short-term use, the use of the term ‘manual therapies’, and links to more information as the information provided in the leaflet was ‘too simplistic’ (Fig. 1). Using this feedback, the leaflet was then modified to suit consumer preferences; examples of this are provided in Fig. 1.

3.2 Healthcare Professional Review Panel

Similarly, the HCPs rated the post-consumer feedback brochure and personal plan’s (ESM D) readability, adequacy, relevance, and usability positively, as shown in Table 3.

Four of 20 HCPs had a sum score of below 16 for the brochure (ESM C). Again, many HCPs who did not fall below the sum score threshold provided valuable feedback. It was then decided that all useful feedback provided, regardless of sum scores, would be implemented.

When asked to provide specific feedback, HCPs found that the brochure was concise and easy to understand, but provided suggestions regarding the language used to describe pain medication and the language used to encourage tapering opioids (Fig. 1). They also suggested using a patient-first approach when designing the personal plan. For example, placing the name of the patient above the name of the general practitioner, in order to empower patients to take ownership of their plan. Three HCPs also suggested including other resources for patients to gain further knowledge and information regarding opioid use and pain management, which we addressed by revising the document containing additional information linked in the brochure to include the clinician-recommended resources (ESM E).

After making the above revisions, a weblink and QR code were embedded into the personal plan to allow for reprinting of additional blank copies (ESM F).

4 Discussion

This study describes an iterative process used to develop consumer leaflets to support the reduction of opioid use in older people with LBP or HoKOA. The process included two review panels consisting of researchers and clinicians, and consumers and carers. Feedback was used to evaluate the perceived usability, acceptability, and credibility of the consumer leaflets and revise the design and language used to maximise clinical effectiveness and future implementation of the intervention.

Although consumer or patient input in the co-production of patient interventions or materials have been increasingly encouraged, involvement of the consumer is variable and rarely conducted in the developmental stages [26, 35, 36]. Other studies have also previously identified a variety of barriers and enablers to deprescribing opioids [17, 37]. Barriers include a lack of patient education leading to a poor understanding of opioids, poor communication with HCPs, and limited alternatives to opioids [17, 37]. Enablers include understanding the negative effects of opioids and the benefits of deprescribing, clear communication and expectations of goals for deprescribing, support for patients and prescribers, and the provision of opportunities for consumer engagement in decision making [17, 37]. In the TANGO study, employing a co-design approach to develop the consumer leaflets was essential to ensure that the materials address the barriers and enablers to deprescribing opioids, and are patient-centred, relevant, and acceptable to our target population. Previous studies have also used similar methods to develop consumer information leaflets in other populations; however, this is the first study to describe the development process of consumer information leaflets aimed to support the reduction of opioid use in older people with LBP or HoKOA [29].

This consumer leaflet was developed as a patient decision aid to assist patients with making the choice to deprescribe their opioids. A systematic review showed that effective deprescribing interventions include an action plan to solve prescribing problems, monitoring of behaviour, the use of a credible source, information about the health consequences of not changing the targeted behaviour, and the benefits of behavioural change [38]. It also showed that studies reporting effectiveness incorporated oral and in-person discussions regarding the implementation of deprescribing recommendations [38]. The consumer leaflets developed in this study incorporate the above elements and may be useful to support prescribers, such as general practitioners, in aiding patients through the deprescribing process [39].

The TANGO consumer leaflets are a potential strategy to support the deprescription of opioids and could potentially be applied to clinical practice if proven effective in future randomised controlled trials. The leaflets have been developed using a rigorous process of gathering feedback from consumers and HCPs. Two people who cared for patients with LBP or HoKOA participated in the consumer panel. Their feedback was consistent with the remaining members of the panel on the perceived usability, acceptability and credibility of the leaflet and personal plan. The carers had identified that the non-drug options for pain management provided had previously benefited them and would be beneficial in the resource. They also agreed that the personal plan would be helpful for them if implemented with a GP’s guidance. However, we acknowledge these perceptions are based on only two carers and may not represent the opinions of all carers. A limitation of our study was the small number (n = 3, 15%) of HCPs who are opioid prescribers. Although the opinions of carers, prescribers and other HCPs are important to consider, it is the perspectives of the consumers (the target group for the leaflets) that should be prioritised.

In addition, all the prescribers indicated that they would not like to provide the personal plan to patients frequently. This is likely to be reflective of the complex nature of the deprescribing process, and the barriers to implementation of this intervention should be explored further prior to a randomised controlled trial.

The consumers recruited into this study had high self-reported health literacy in one or more domains. Given that only 39% of Australians above 65 years of age have high self-reported health literacy [40], we decided to further assess the readability of the brochure using the Flesch–Kincaid Grade level [33, 34]. The final brochure presented a readability level of grade 8.6, which meets the recommended health information readability level of grade 8 (12–14 years of age, with 8 years of Australian education) [32]. Taken together, these data suggest that the language used in the brochure is appropriate for most English-speaking Australians, including our target population of older adults.

The TANGO brochure and personal plan were evaluated in a consumer group who primarily had knowledge of opioid medications, with 67% having taken an opioid once before. Although this pre-existing knowledge may have potentially introduced bias when assessing their comprehension of the information in the resource, their lived experience of musculoskeletal pain and pain management was sought to ensure the information was highly relevant to this particular patient group. The survey was distributed online to maximise participation, however it could therefore not be determined whether any participants sought additional help or clarification from family or peers while completing their review. Additional rounds of review, including inclusion of more carers, should be considered in future studies to identify if further revisions are required.

This study led to the development of a leaflet and personal plan to support the reduction of opioid use in older people with LBP or HoKOA. The development of the consumer leaflets incorporated feedback provided by HCPs and consumers. More research is required to assess the role of the consumer leaflets in supporting the deprescription of opioids in this clinical population in practice. A future randomised clinical trial will assess the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing opioid use in older people with LBP as an adjunct to usual care.

References

Mathieson S, et al. What proportion of patients with chronic noncancer pain are prescribed an opioid medicine? Systematic review and meta-regression of observational studies. J Intern Med. 2020;287(5):458–74.

Harrison CM, et al. Opioid prescribing in Australian general practice. Med J Aust. 2012;196(6):380–1.

Larochelle MR, et al. Trends in opioid prescribing and co-prescribing of sedative hypnotics for acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain: 2001–2010. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(8):885–92.

Foster NE, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2368–83.

Megale RZ, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral and transdermal opioid analgesics for musculoskeletal pain in older adults: a systematic review of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Pain. 2018;19(5):475.e1-475.e24.

McAlindon TE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(3):363–88.

White R, et al. General practitioners and management of chronic noncancer pain: a cross-sectional survey of influences on opioid deprescribing. J Pain Res. 2019;12:467–75.

Baldini A, Von Korff M, Lin EHB. A review of potential adverse effects of long-term opioid therapy: a practitioners guide. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(3):27252.

Deyo RA, Von Korff M, Duhrkoop D. Opioids for low back pain. BMJ. 2015;350: g6380.

Sullivan MD, Howe CQ. Opioid therapy for chronic pain in the United States: promises and perils. Pain. 2013;154(Suppl 1):S94-100.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Opioid harm in Australia and comparisons between Australia and Canada. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2018.

Florence CS, et al. The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse and dependence in the United States, 2013. Med Care. 2016;54(10):901–6.

Ackerman IN, et al. Forecasting the future burden of opioids for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018;26(3):350–5.

Virnes R, et al. Opioids and falls risk in older adults: a narrative review. Drugs Aging. 2022;39(3):199–207.

Chau DL, et al. Opioids and elderly: use and side effects. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(2):273–8.

West NA, Dart RC. Prescription opioid exposures and adverse outcomes among older adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(5):539–44.

Cross AJ, et al. Barriers and enablers to monitoring and deprescribing opioid analgesics for chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review with qualitative evidence synthesis using the Theoretical Domains Framework. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31(5):387–400.

Hamilton M, et al. Barriers, facilitators, and resources to opioid deprescribing in primary care: experiences of general practitioners in Australia. PAIN. 2022;163(4):e518–e526.

Reeve E, et al. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):793–807.

Niznik, J.D., Ferreri, S.P., Armistead, L.T. et al. Primary-Care Prescribers’ Perspectives on Deprescribing Opioids and Benzodiazepines in Older Adults. Drugs Aging 39, 739–748 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-022-00967-6

Reeve E, Low LF, Hilmer SN. Beliefs and attitudes of older adults and carers about deprescribing of medications: a qualitative focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(649):e552–60.

Weir K, et al. Decision-making preferences and deprescribing: perspectives of older adults and companions about their medicines. J Gerontol Ser B. 2018;73(7):e98–107.

Turner JP, et al. Strategies to promote public engagement around deprescribing. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9(11):653–65.

Tannenbaum C, et al. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):890–8.

Dollman WB, et al. Achieving a sustained reduction in benzodiazepine use through implementation of an area-wide multi-strategic approach. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30(5):425–32.

Greenhalgh T, et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: Systematic review and co-design pilot. Health Expect. 2019;22(4):785.

Raynor DK, Dickinson D. Key principles to guide development of consumer medicine information—content analysis of information design texts. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(4):700–6.

Martin P, et al. An educational intervention to reduce the use of potentially inappropriate medications among older adults (EMPOWER study): protocol for a cluster randomized trial. Trials. 2013;14(1):80–80.

Jokanovic N, et al. Development of consumer information leaflets for deprescribing in older hospital inpatients: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12): e033303.

Chew LD, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–6.

Lewis JR. IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. Int J Hum-Comput Int. 1995;7(1):57–78.

Australian Commission on Safety Quality in Health Care. Health literacy: taking action to improve safety and quality. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2015.

Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32(3):221.

Kincaid JP, et al. Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count and flesch reading ease formula) for navy enlisted personnel. Naval Technical Training Command, Millington TN Research Branch; 1975.

Raynor DK. User testing in developing patient medication information in Europe. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(5):640–5.

Blackburn S, et al. The extent, quality and impact of patient and public involvement in primary care research: a mixed methods study. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4(1):16–16.

Langford AV, et al. “The lesser of two evils”: a framework analysis of consumers’ perspectives on opioid deprescribing and the development of opioid deprescribing guidelines. Pain. 2021;162(11):2686–92.

Hansen CR, et al. Identification of behaviour change techniques in deprescribing interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(12):2716–28.

Reeve E. Deprescribing tools: a review of the types of tools available to aid deprescribing in clincal practice. J Pharm Pract Res. 2020;50(1):98–107.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Health literacy survey. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This study was funded by the North Sydney Local Health District Research Fund, NSW, Australia. DJH and MLF hold research fellowships from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Conflict of interest

Alessandra C. Marcelo, Emma K. Ho, Sarah N. Hilmer, Natali Jokanovic, Joanna Prior, Ana Paula Carvalho-e-Silva and Manuela L. Ferreira declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article. David J. Hunter provides consulting advice on scientific advisory boards for Pfizer, Lilly, TLCBio, Novartis, Tissuegene, and Biobone that has no relation to the submitted paper.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Northern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (Project Number: 2020/570).

Consent to participate

Informed consent regarding the participation and publication of de-identified data was obtained from all individual participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data generated and/or analysed during the current study are included in this published article and its electronic supplementary information files.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation was performed by EH, NJ, MF, DH and SH. Data collection and analysis were performed by AM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AM and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Summary slides are available in the online version of the article as Supplementary Material.

Supplementary file2 (MP4 9135 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marcelo, A.C., Ho, E.K., Hunter, D.J. et al. TANGO: Development of Consumer Information Leaflets to Support TAperiNG of Opioids in Older Adults with Low Back Pain and Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis. Drugs Aging 40, 343–354 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-023-01011-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-023-01011-x