Abstract

Background

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) have been associated with an increased risk of starting antimuscarinic treatment to treat overactive bladder (OAB)—an example of a prescribing cascade. Limited comparative data exist regarding the prescribing cascade of antimuscarinics across individual AChEIs in older adults with dementia.

Objective

This study examined the association between individual AChEI use and antimuscarinic cascade in older adults with dementia.

Methods

We conducted a new user retrospective cohort study from January 2005 to December 2018 using data from the TriNetX electronic medical record database, a federated electronic medical records network in the US. The cohort included patients 65 years or older with a diagnosis of dementia using AChEIs (donepezil, galantamine, or rivastigmine). Individual AChEIs were identified with index dates from 1 January 2006 to 31 June 2018, with a 1-year washout period. The study excluded patients with any antimuscarinic use and OAB diagnosis 1 year before the AChEI index date. The primary outcome of interest was the prescription of antimuscarinics within 6 months of the AChEI index date. A Cox proportional hazard model was used to assess the association between individual incident AChEI use and antimuscarinic prescribing cascade after controlling for several covariates.

Results

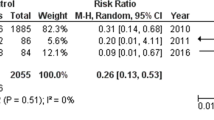

The study included 47,059 older adults with dementia who were incident users of AChEIs. Most of these patients were initiated with donepezil (83.1%), followed by rivastigmine (12.3%) and galantamine (4.6%). Overall, 8.16% of the study cohort had incident OAB diagnosis or antimuscarinic prescription. Antimuscarinics were initiated by 1725 (3.7%) older adults with dementia within 6 months of AChEI prescription, and cascade varied widely across individual agents—donepezil (3.9%), rivastigmine (2.6%), and galantamine (2.9%). Cox proportional hazard analyses revealed that donepezil users had an increased risk of receiving antimuscarinics (adjusted hazard ratio 1.55, 95% confidence interval 1.31–1.83) compared with rivastigmine. The findings were consistent in sensitivity analyses.

Conclusion

This study found that donepezil use is more likely to lead to antimuscarinic cascade than rivastigmine. Future studies are needed to determine the potential consequences of this cascade in dementia.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alzheimer’s Assocation Report. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(3):391–460.

APA Workgroup on Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, Rabins PV, Blacker D, et al. American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(12 Suppl):5–56.

Rabins PV, Rovner BW, Rummans T, Schneider LS, Tariot PN. Guideline Watch (October 2014): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2017;15(1):110–28.

McGleenon BM, Dynan KB, Passmore AP. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48(4):471–80.

Ouslander JG. Management of overactive bladder. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(8):786–99.

Gill SS, Mamdani M, Naglie G, et al. A prescribing cascade involving cholinesterase inhibitors and anticholinergic drugs. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):808–13.

Hashimoto M, Imamura T, Tanimukai S, Kazui H, Mori E. Urinary incontinence: an unrecognised adverse effect with donepezil. Lancet. 2000;356(9229):568.

Apostolidis A. Antimuscarinics in the treatment of OAB: is there a first-line and a second-line choice? Curr Drug Targets. 2015;16(11):1187–97.

Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. Optimising drug treatment for elderly people: the prescribing cascade. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1096–9.

Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. The prescribing cascade revisited. Lancet. 2017;389(10081):1778–80.

American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria© Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616–31.

Croke L. Beers criteria for inappropriate medication use in older patients: an update from the AGS. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(1):56–7.

Geoffrion R, Urogynaecology C. Treatments for overactive bladder: focus on pharmacotherapy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34(11):1092–101.

Lampela P, Taipale H, Hartikainen S. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors increases initiation of urinary anticholinergics in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(7):1510–2.

Suh DC, Arcona S, Thomas SK, et al. Risk of antipsychotic drug use in patients with Alzheimer’s disease treated with rivastigmine. Drugs Aging. 2004;21(6):395–403.

Stapff M, Hilderbrand S. First-line treatment of essential hypertension: a real-world analysis across four antihypertensive treatment classes. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019;21(5):627–34.

Topaloglu U, Palchuk MB. Using a federated network of real-world data to optimize clinical trials operations. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018;2:1–10.

Stapff MP. Using real world data to assess cardiovascular outcomes of two antidiabetic treatment classes. World J Diabetes. 2018;9(12):252–7.

Stapff MP, Palm S. More on long-term effects of finasteride on prostate cancer mortality. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(20):e38.

Wyndaele JJ. Antimuscarinics for the treatment of neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Spinal Cord. 2013;51(6):431.

Colovic MB, Krstic DZ, Lazarevic-Pasti TD, Bondzic AM, Vasic VM. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: pharmacology and toxicology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2013;11(3):315–35.

Lightner DJ, Gomelsky A, Souter L, Vasavada SP. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline Amendment 2019. J Urol. 2019;202(3):558–63.

Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1973;51(1):95–124.

Chekani F, Holmes HM, Johnson ML, Chen H, Sherer JT, Aparasu RR. Use of atypical antipsychotics in long-term care residents with Parkinson’s disease and comorbid depression. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2020;12:23–30.

Chatterjee S, Mehta S, Sherer JT, Aparasu RR. Prevalence and predictors of anticholinergic medication use in elderly nursing home residents with dementia: analysis of data from the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(12):987–97.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10.

Kachru N, Holmes HM, Johnson ML, Chen H, Aparasu RR. Risk of mortality associated with non-selective antimuscarinic medications in older adults with dementia: a retrospective study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(7):2084–93.

Kamble P, Chen H, Sherer JT, Aparasu RR. Use of antipsychotics among elderly nursing home residents with dementia in the US: an analysis of National Survey Data. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(6):483–92.

Kobayashi H, Ohnishi T, Nakagawa R, Yoshizawa K. The comparative efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(8):892–904.

Bryson HM, Benfield P. Donepezil. Drugs Aging. 1997;10(3):234–9 (discussion 240–231).

Forette F, Anand R, Gharabawi G. A phase II study in patients with Alzheimer’s disease to assess the preliminary efficacy and maximum tolerated dose of rivastigmine (Exelon). Eur J Neurol. 1999;6(4):423–9.

Lilienfeld S. Galantamine—a novel cholinergic drug with a unique dual mode of action for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drug Rev. 2002;8(2):159–76.

Grossberg GT. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: getting on and staying on. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2003;64(4):216–35.

Sakakibara R, Ogata T, Uchiyama T, et al. How to manage overactive bladder in elderly individuals with dementia? A combined use of donepezil, a central acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, and propiverine, a peripheral muscarine receptor antagonist. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1515–7.

Scali C, Casamenti F, Bellucci A, Costagli C, Schmidt B, Pepeu G. Effect of subchronic administration of metrifonate, rivastigmine and donepezil on brain acetylcholine in aged F344 rats. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2002;109(7–8):1067–80.

Cetinel B, Onal B. Rationale for the use of anticholinergic agents in overactive bladder with regard to central nervous system and cardiovascular system side effects. Korean J Urol. 2013;54(12):806–15.

Arana A, Margulis AV, McQuay LJ, et al. Variation in cardiovascular risk related to individual antimuscarinic drugs used to treat overactive bladder: a UK cohort study. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38(6):628–37.

Reeve E, Farrell B, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in dementia: guideline summary. Med J Aust. 2019;210(4):174–9.

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827–34.

Chen JL, Chen SF, Jiang YH, Kuo HC. Practical points in the medical treatment of overactive bladder and nocturia in the elderly. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2016;28(1):1–5.

Vouri SM, Schootman M, Strope SA, Xian H, Olsen MA. Antimuscarinic use and discontinuation in an older adult population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;80:1–11.

Palmer MH, Hardin SR, Behrend C, Collins SK, Madigan CK, Carlson JR. Urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in patients with heart failure. J Urol. 2009;182(1):196–202.

Solmaz V, Albayrak S, Tekatas A, et al. Evaluation of overactive bladder in male antidepressant users: a prospective study. Int Neurourol J. 2017;21(1):62–7.

Movig KL, Leufkens HG, Belitser SV, Lenderink AW, Egberts AC. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced urinary incontinence. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11(4):271–9.

Lai HH, Helmuth ME, Smith AR, et al. Relationship between central obesity, general obesity, overactive bladder syndrome and urinary incontinence among male and female patients seeking care for their lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology. 2019;123:34–43.

Lin WY, Andersson KE, Lin CL, Kao CH, Wu HC. Association of lower urinary tract syndrome with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0170288.

Wein A. Symptom-based diagnosis of overactive bladder: an overview. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5(5 Suppl 2):S135-136.

Vouri SM, Kebodeaux CD, Stranges PM, Teshome BF. Adverse events and treatment discontinuations of antimuscarinics for the treatment of overactive bladder in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;69:77–96.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used for the conduct of this study or the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

Rajender R. Aparasu has received research funding from Astellas Inc., Incyte Corp., Gilead, and Novartis Inc. for projects unrelated to the current work. Prajakta P. Masurkar, Satabdi Chatterjee, and Jeffrey T. Sherer declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Ethical approval/informed consent

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Houston under the exempt category.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Data are not available due to data use restriction agreements with TriNetX. Data can be directly obtained from TriNetX.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

PPM and RRA had full access to all the study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: All authors. Acquisition of data: RRA. Analysis and interpretation of data: PPM, SC, and RR Aparasu. Drafting of the manuscript: PPM. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: SC, JC, and RRA. Statistical analysis: PPM and SC. Administrative, technical, or material support: RRA. Study supervision: SC and RRA. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Masurkar, P.P., Chatterjee, S., Sherer, J.T. et al. Antimuscarinic Cascade Across Individual Cholinesterase Inhibitors in Older Adults with Dementia. Drugs Aging 38, 593–602 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-021-00863-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-021-00863-5