Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a chronic, multifactorial disease and a leading cause of irreversible blindness in the elderly population in the Western Hemisphere. Among the two major subtypes of AMD, the prevalence of the nonneovascular (dry) type is approximately 85–90% and the neovascular (wet) type is 10–15%. Healthy lifestyle and nutritional supplements of anti-oxidative micronutrients have been shown to delay the progression of dry AMD and lower the risk of development of wet AMD, and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections have been shown to improve visual acuity for wet AMD patients. However, to date, there is no approved treatment for geographic atrophy (GA), a debilitating late stage of dry AMD. Thus, this represents a large unmet need in this patient population. This review focuses on the current management and treatment of nonneovascular AMD, the drugs and devices that have been under investigation for the treatment of GA, and the latest clinical trial results. A few therapeutic options have shown initial promising clinical trial results, but failed to show efficacy in larger trials, while others are awaiting future clinical trial results and long-term follow-up to evaluate safety and efficacy.

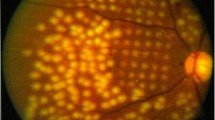

Source: Garrity et al. [97]

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Klein R, Cruickshanks KJ, Nash SD, et al. The prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and associated risk factors. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 2010;128(6):750–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.92.

Lim LS, Mitchell P, Seddon JM, Holz FG, Wong TY. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet LondEngl. 2012;379(9827):1728–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60282-7.

Klein R, Klein BEK, Tomany SC, Moss SE. Ten-year incidence of age-related maculopathy and smoking and drinking: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(7):589–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf092.

Klein R, Klein BEK, Tomany SC, Cruickshanks KJ. The association of cardiovascular disease with the long-term incidence of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(6):1273–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00599-2.

Mares-Perlman JA, Brady WE, Klein R, VandenLangenberg GM, Klein BE, Palta M. Dietary fat and age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 1995;113(6):743–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1995.01100060069034.

Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Fine SL. Age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;32(6):375–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-6257(88)90052-5.

Erke MG, Bertelsen G, Peto T, Sjølie AK, Lindekleiv H, Njølstad I. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in elderly Caucasians: the Tromsø Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(9):1737–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.016.

Holz FG, Strauss EC, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, van Lookeren CM. Geographic atrophy: clinical features and potential therapeutic approaches. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):1079–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.023.

Chiu C-J, Chang M-L, Zhang FF, et al. The relationship of major American dietary patterns to age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(1):118–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2014.04.016 (e1).

Wang JJ, Buitendijk GHS, Rochtchina E, et al. Genetic susceptibility, dietary antioxidants, and long-term incidence of age-related macular degeneration in two populations. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(3):667–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.017.

Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 2001;119(10):1417–36. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417.

Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research Group. Lutein + zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids for age-related macular degeneration: the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309(19):2005–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.4997.

Druesne-Pecollo N, Latino-Martel P, Norat T, et al. Beta-carotene supplementation and cancer risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(1):172–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.25008.

Aronow ME, Chew EY. AREDS2: perspectives, recommendations, and unanswered questions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25(3):186–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0000000000000046.

Ramírez C, Cáceres-del-Carpio J, Chu J, et al. Brimonidine can prevent in vitro hydroquinone damage on retinal pigment epithelium cells and retinal Müller cells. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther Off J Assoc Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2016;32(2):102–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/jop.2015.0083.

Saylor M, McLoon LK, Harrison AR, Lee MS. Experimental and clinical evidence for brimonidine as an optic nerve and retinal neuroprotective agent: an evidence-based review. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 2009;127(4):402–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.9.

Ghosn C, Almazan A, Decker S, Burke JA. Brimonidine drug delivery system (Brimo DDS Generation 1) slows the growth of retinal pigment epithelial hypofluorescence following regional blue light irradiation in a nonhuman primate (NHP) model of geographic atrophy (GA). Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(8):1960–1960.

Freeman WR, Bandello F, Souied EH, et al. Phase 2b study of brimonidine DDS: potential novel treatment for geographic atrophy. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(9):971–971.

Retinal Physician-Brimonidine Drug Delivery System for Geographic Atrophy. Retinal Physician. https://www.retinalphysician.com/issues/2019/november-2019/brimonidine-drug-delivery-system-for-geographic-at. Accessed 3 Dec 2019.

Fuhrmann S, Grabosch K, Kirsch M, Hofmann H-D. Distribution of CNTF receptor alpha protein in the central nervous system of the chick embryo. J Comp Neurol. 2003;461(1):111–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.10701.

Kauper K, McGovern C, Sherman S, et al. Two-year intraocular delivery of ciliary neurotrophic factor by encapsulated cell technology implants in patients with chronic retinal degenerative diseases. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(12):7484–91. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-9970.

Luibl V, Isas JM, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Langen R, Chen J. Drusen deposits associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration contain nonfibrillar amyloid oligomers. J Clin Investig. 2006;116(2):378–85. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI25843.

Johnson LV, Leitner WP, Rivest AJ, Staples MK, Radeke MJ, Anderson DH. The Alzheimer’s A beta-peptide is deposited at sites of complement activation in pathologic deposits associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(18):11830–5. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.192203399.

Landa G, Butovsky O, Shoshani J, Schwartz M, Pollack A. Weekly vaccination with Copaxone (glatiramer acetate) as a potential therapy for dry age-related macular degeneration. Curr Eye Res. 2008;33(11):1011–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/02713680802484637.

Kaplan Medical Center. Subcutaneous Copaxone as Treatment for Dry Age Related Macular Degeneration. clinicaltrials.gov; 2007. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00466076. Accessed 5 Nov 2020.

Rosenfeld PJ, Berger B, Reichel E, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of an anti-amyloid β monoclonal antibody in geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2(10):1028–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oret.2018.03.001.

Ding J-D, Lin J, Mace BE, Herrmann R, Sullivan P, Bowes RC. Targeting age-related macular degeneration with Alzheimer’s disease based immunotherapies: anti-amyloid-beta antibody attenuates pathologies in an age-related macular degeneration mouse model. Vis Res. 2008;48(3):339–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2007.07.025.

Pfizer. A phase 2 multi-center, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, multi-dose study to investigate the efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Rn6g (Pf-04382923). In: subjects with geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. clinicaltrials.gov; 2016. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT01577381. Accessed 4 Nov 2020

Parsons CG, Ruitenberg M, Freitag CE, Sroka-Saidi K, Russ H, Rammes G. MRZ-99030—a novel modulator of Aβ aggregation: I—mechanism of action (MoA) underlying the potential neuroprotective treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Neuropharmacology. 2015;92:158–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.12.038.

Clinical Trials. Galimedix Therapeutics, Inc. https://www.galimedix.com/clinical-trials. Accessed 7 Nov 2020.

Mihai DM, Washington I. Vitamin A dimers trigger the protracted death of retinal pigment epithelium cells. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(7):e1348. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2014.314.

Issa PC, Barnard AR, Washington I, MacLaren RE. C20-D3-Vitamin A (ALK-001) rescues the phenotype of an Abca4−/− mouse model of Stargardt disease. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(13):5015.

Alkeus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. A Phase 1, Open Label, Repeat Dose Study to Investigate the Safety and Pharmacokinetics of 4-Week Daily Dosing of ALK-001 in Healthy Volunteers. clinicaltrials.gov; 2015. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02230228. Accessed 21 June 2020.

Alkeus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. A Phase 2/3 Multicenter, randomized, double-masked, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study to investigate the safety, pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and efficacy of ALK-001 in geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. clinicaltrials.gov; 2019. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03845582. Accessed 21 June 2020.

Bavik C, Henry SH, Zhang Y, et al. Visual cycle modulation as an approach toward preservation of retinal integrity. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0124940. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124940.

Rosenfeld PJ, Dugel PU, Holz FG, et al. Emixustat hydrochloride for geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: a randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(10):1556–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.03.059.

Brown EE, Lewin AS, Ash JD. Mitochondria: potential targets for protection in age-related macular degeneration. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1074:11–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75402-4_2.

Cousins SW, Saloupis P, Brahmajoti MV, Mettu PS. Mitochondrial dysfunction in experimental mouse models of SubRPE deposit formation and reversal by the Mito-reparative drug MTP-131. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(12):2126–2126.

Retinal Physician-The ReCLAIM Phase 1 Clinical Trial of Elamipretide for Dry AMD. Retinal Physician. https://www.retinalphysician.com/issues/2019/november-2019/the-reclaim-phase-1-clinical-trial-of-elamipretide. Accessed 23 June 2020.

Stealth BioTherapeutics Announces Positive Results for Elamipretide in Ophthalmic Conditions. BioSpace. https://www.biospace.com/article/stealth-biotherapeutics-announces-positive-results-for-elamipretide-in-ophthalmic-conditions/. Accessed 22 Nov 2019.

Kuppermann B. Risuteganib for Intermediate Dry AMD. Retina Physician. 16(November/December 2019):28, 30, 31.

Quiroz-Mercado H. Randomized, Prospective, Double-Masked, Controlled Phase 2b Trial to Evaluate the Safety & Efficacy of ALG-1001 (Luminate®) in Diabetic Macular Edema. In: Presented at the: The Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology; April 2018; Honolulu, Hawaii.

Yang P, Neal SE, Jaffe GJ. Luminate protects against hydroquinone-induced injury in human RPE cells. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(9):1944–1944.

Kenney CM, Chwa M, Cáceres-del-Carpio J, et al. Effects of anti-VEGF and ALG-1001 on human retinal cells in vitro. In: Presented at the: Association for Research and Vision in Ophthalmology Annual Meeting; April 29, 2018; Honolulu, Hawaii.

Kaiser P. Safety and efficacy of risuteganib in intermediate non-exudative age-related macular degeneration—first time results from a phase 2 study. In: Presented at the: American Society of Retina Specialists Annual Meeting; July 27, 2019; Chicag, Illinois.

Ophthalmics A, LLC. Bausch Health to Acquire Option to Purchase All Ophthalmology Assets of Allegro Ophthalmics. Allegro ophthalmics-from theory to therapy. Published September 21, 2020. https://www.allegroeye.com/bausch-health-to-acquire-option-to-purchase-all-ophthalmology-assets-of-allegro-ophthalmics/. Accessed 5 Nov 2020.

Booij JC, Baas DC, Beisekeeva J, Gorgels TGMF, Bergen AAB. The dynamic nature of Bruch’s membrane. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.08.003.

Effects of hydralazine on ocular blood flow and laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. http://www.ijo.cn/gjyken/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?file_no=200904011. Accessed 11 June 2020.

Ralston JPG, Sloan D, Waters-Honcu D, Saigal S, Torkildsen G. A pilot, open-label study of the safety of MC-1101 in both normal volunteers and patients with early nonexudative age-related macular degeneration. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(13):913–913.

Johnson LV, Leitner WP, Staples MK, Anderson DH. Complement activation and inflammatory processes in Drusen formation and age related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73(6):887–96. https://doi.org/10.1006/exer.2001.1094.

Hageman GS, Luthert PJ, Victor Chong NH, Johnson LV, Anderson DH, Mullins RF. An integrated hypothesis that considers drusen as biomarkers of immune-mediated processes at the RPE-Bruch’s membrane interface in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20(6):705–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00010-6.

Johnson LV, Ozaki S, Staples MK, Erickson PA, Anderson DH. A potential role for immune complex pathogenesis in Drusen formation. Exp Eye Res. 2000;70(4):441–9. https://doi.org/10.1006/exer.1999.0798.

Mullins RF, Aptsiauri N, Hageman GS. Structure and composition of Drusen associated with glomerulonephritis: implications for the role of complement activation in Drusen biogenesis. Eye Lond Engl. 2001;15(Pt 3):390–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2001.142.

Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, et al. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(20):7227–32. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0501536102.

Haines JL, Hauser MA, Schmidt S, et al. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308(5720):419–21. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1110359.

Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, et al. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308(5720):385–9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1109557.

Maller J, George S, Purcell S, et al. Common variation in three genes, including a noncoding variant in CFH, strongly influences risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2006;38(9):1055–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1873.

Gold B, Merriam JE, Zernant J, et al. Variation in factor B (BF) and complement component 2 (C2) genes is associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2006;38(4):458–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1750.

Yates JRW, Sepp T, Matharu BK, et al. Complement C3 variant and the risk of age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):553–61. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa072618.

Machalińska A, Dziedziejko V, Mozolewska-Piotrowska K, Karczewicz D, Wiszniewska B, Machaliński B. Elevated plasma levels of C3a complement compound in the exudative form of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Res. 2009;42(1):54–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000219686.

Scholl HPN, CharbelIssa P, Walier M, et al. Systemic complement activation in age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2593. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002593.

Gemini Therapeutics Enrolls First Patient in Phase 2a Study of GEM103 for Dry Age-related Macular Degeneration. BioSpace. https://www.biospace.com/article/gemini-therapeutics-enrolls-first-patient-in-phase-2a-study-of-gem103-for-dry-age-related-macular-degeneration/. Accessed 5 Nov 2020.

Yaspan BL, Williams DF, Holz FG, et al. Targeting factor D of the alternative complement pathway reduces geographic atrophy progression secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Sci Transl Med. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf1443.

Holz FG, Sadda SR, Busbee B, et al. Efficacy and safety of lampalizumab for geographic atrophy due to age-related macular degeneration: chroma and spectri phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(6):666–77. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.1544.

Yehoshua Z, de Garcia Filho CAA, Nunes RP, et al. Systemic complement inhibition with eculizumab for geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: the COMPLETE study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(3):693–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.044.

October 28, 2019. Zimura phase 2b trial results positive in geographic atrophy secondary to dry AMD. https://www.healio.com/ophthalmology/retina-vitreous/news/online/06c578df-d806-4481-9f6d-85f956fe0e67/zimura-phase-2b-trial-results-positive-in-geographic-atrophy-secondary-to-dry-amd. Accessed 3 Dec 2019.

Liao DS, Grossi FV, El Mehdi D, et al. Complement C3 inhibitor pegcetacoplan for geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: a randomized phase 2 trial. Ophthalmology. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.07.011 (Published online July 16).

Hemera Biosciences. A phase 1, open-label, multi-center, dose-escalating, safety and tolerability study of a single intravitreal injection of AAVCAGsCD59 in patients with advanced non-exudative (Dry) age-related macular degeneration with geographic atrophy. clinicaltrials.gov; 2019. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03144999. Accessed 15 June 2020.

Dugel P. CLINICAL TRIAL DOWNLOAD: data on a gene therapy for dry and wet AMD. Retina Physician. 17(April 2020):16, 17.

Schwartz SD, Hubschman J-P, Heilwell G, et al. Embryonic stem cell trials for macular degeneration: a preliminary report. Lancet Lond Engl. 2012;379(9817):713–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60028-2.

Schwartz SD, Regillo CD, Lam BL, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in patients with age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt’s macular dystrophy: follow-up of two open-label phase 1/2 studies. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015;385(9967):509–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61376-3.

Schwartz SD, Tan G, Hosseini H, Nagiel A. Subretinal transplantation of embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium for the treatment of macular degeneration: an assessment at 4 years. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(5):ORSFc1-9. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.15-18681.

Song WK, Park K-M, Kim H-J, et al. Treatment of macular degeneration using embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium: preliminary results in Asian patients. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4(5):860–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.04.005.

Kashani AH, Lebkowski JS, Rahhal FM, et al. A bioengineered retinal pigment epithelial monolayer for advanced, dry age-related macular degeneration. Sci Transl Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aao4097.

Diniz B, Thomas P, Thomas B, et al. Subretinal implantation of retinal pigment epithelial cells derived from human embryonic stem cells: improved survival when implanted as a monolayer. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(7):5087–96. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-11239.

da Cruz L, Fynes K, Georgiadis O, et al. Phase 1 clinical study of an embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium patch in age-related macular degeneration. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(4):328–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4114.

Mandai M, Watanabe A, Kurimoto Y, et al. Autologous induced stem-cell-derived retinal cells for macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1038–46. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1608368.

Fujimoto JG, Pitris C, Boppart SA, Brezinski ME. Optical coherence tomography: an emerging technology for biomedical imaging and optical biopsy. Neoplasia NYN. 2000;2(1–2):9–25.

Kashani AH, Uang J, Mert M, et al. Surgical method for implantation of a biosynthetic retinal pigment epithelium monolayer for geographic atrophy: experience from a phase 1/2a study. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(3):264–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oret.2019.09.017.

Riemann CD, Banin E, Barak A, et al. Phase I/IIa clinical trial of human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE, OpRegen) transplantation in advanced dry form age-related macular degeneration (AMD): interim results. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61(7):865–865.

Gass JD. Photocoagulation of macular lesions. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1971;75(3):580–608.

Complications of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Prevention Trial Research Group. Laser treatment in patients with bilateral large Drusen: the complications of age-related macular degeneration prevention trial. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(11):1974–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.015.

Querques G, Cicinelli MV, Rabiolo A, et al. Laser photocoagulation as treatment of non-exudative age-related macular degeneration: state-of-the-art and future perspectives. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-017-3848-x.

Virgili G, Michelessi M, Parodi MB, Bacherini D, Evans JR. Laser treatment of drusen to prevent progression to advanced age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006537.pub3.

Jobling AI, Guymer RH, Vessey KA, et al. Nanosecond laser therapy reverses pathologic and molecular changes in age-related macular degeneration without retinal damage. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am SocExp Biol. 2015;29(2):696–710. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.14-262444.

Guymer RH, Wu Z, Hodgson LAB, et al. Subthreshold nanosecond laser intervention in age-related macular degeneration: the LEAD randomized controlled clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(6):829–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.09.015.

Grossman N, Schneid N, Reuveni H, Halevy S, Lubart R. 780 nm low power diode laser irradiation stimulates proliferation of keratinocyte cultures: involvement of reactive oxygen species. Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22(4):212–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1998)22:4%3c212::aid-lsm5%3e3.0.co;2-s.

Karu T. Primary and secondary mechanisms of action of visible to near-IR radiation on cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1999;49(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1011-1344(98)00219-X.

Karu T, Pyatibrat L, Kalendo G. Irradiation with He–Ne laser increases ATP level in cells cultivated in vitro. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1995;27(3):219–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/1011-1344(94)07078-3.

Wong-Riley MTT, Liang HL, Eells JT, et al. Photobiomodulation directly benefits primary neurons functionally inactivated by toxins: role of cytochrome c oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(6):4761–71. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M409650200.

Eells JT, Wong-Riley MTT, VerHoeve J, et al. Mitochondrial signal transduction in accelerated wound and retinal healing by near-infrared light therapy. Mitochondrion. 2004;4(5–6):559–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.033.

Eells JT, Henry MM, Summerfelt P, et al. Therapeutic photobiomodulation for methanol-induced retinal toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(6):3439–44. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0534746100.

Gkotsi D, Begum R, Salt T, et al. Recharging mitochondrial batteries in old eyes. Near infra-red increases ATP. Exp Eye Res. 2014;122:50–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2014.02.023.

Albarracin R, Eells J, Valter K. Photobiomodulation protects the retina from light-induced photoreceptor degeneration. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(6):3582–92. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.10-6664.

Tang J, Du Y, Lee CA, Talahalli R, Eells JT, Kern TS. Low-intensity far-red light inhibits early lesions that contribute to diabetic retinopathy: in vivo and in vitro. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(5):3681–90. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-11018.

Markowitz SN, Devenyi RG, Munk MR, et al. A double-masked, randomized, sham-controlled, single-center study with photobiomodulation for the treatment of dry age-related macular degeneration. Retina Phila Pa. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000002632 (Published online August 9).

Garrity ST, Sarraf D, Freund KB, Sadda SR. Multimodal imaging of nonneovascular age-related macular degeneration. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018;59(4):AMD48–AMD64

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

None.

Conflict of interest

JK: the author declares no competing interest. EML: consultant—Apellis, Roche, Novartis, Allegro, Galimedix, IMI-2 Consortium, Retrotope, and Gemini Therapeutics; research support—Roche, Apellis, Novartis, Neurotech, Astellas, Allegro, and LumiThera.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

None.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, JB., Lad, E.M. Therapeutic Options Under Development for Nonneovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Geographic Atrophy. Drugs Aging 38, 17–27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-020-00822-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-020-00822-6