Abstract

The use of psychotropic drugs (antipsychotics, benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-related drugs, and antidepressants) is common, with a prevalence estimates range of 19–29% among community dwelling older adults. These drugs are often prescribed for off-label use, including neuropsychiatric symptoms. The older adult population also has high rates of pneumonia and some of these cases may be associated with adverse drug events. In this narrative review, we summarize the findings from current observational studies on the association between psychotropic drug use and pneumonia in older adults. In addition to studies assessing the use of psychotropics, we included antiepileptic drugs, as they are also central nervous system-acting drugs, whose use is becoming more common in the aging population. The use of antipsychotics, benzodiazepine, and benzodiazepine-related drugs are associated with increased risk of pneumonia in older adults (≥ 65 years of age), and these findings are not limited to this age group. Minimal and conflicting evidence has been reported on the association between antidepressant drug use and pneumonia, but differences between study populations make it difficult to compare findings. Studies regarding antiepileptic drug use and risk of pneumonia in older persons are lacking, although an increased risk of pneumonia in antiepileptic drug users compared with non-users in persons with Alzheimer’s disease has been reported. Tools such as the American Geriatric Society Beers Criteria and the STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate medications aids prescribers to avoid these drugs in order to reduce the risk of adverse drug events. However, risk of pneumonia is not mentioned in the current criteria and more research on this topic is needed, especially in vulnerable populations, such as persons with dementia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Antipsychotic, and benzodiazepine and benzodiazepine-related drug use is associated with an increased risk of pneumonia in older adults. |

Only a few studies have been performed on the association between antidepressant or antiepileptic use and pneumonia. More studies are needed to verify the few findings of drug use and risk of pneumonia. |

The current AGS Beers Criteria and STOPP/START Criteria have no specific comment on avoidance of psychotropics or groups of psychotropics due to the risk of pneumonia in older adults. However, avoiding them is advised based on evidence of other adverse events. |

1 Introduction

Pneumonia is a common and serious infection in older adults (persons aged 65 years or older), often leading to hospitalizations, and is a leading diagnosis of acute cause of death in this population [1,2,3]. In the United States (US), hospitalization from infection-related causes comprised 12–19% of all hospitalizations in adults over 65 years old, with the main cause of infections being infections of the lower respiratory tract (46%) from 1990 through 2002 [4]. From 2000 to 2010 in the US, the rate of hospitalization for pneumonia decreased by around 30% among those aged 65 years [5], but European studies have reported contradicting results during a similar time period [6,7,8]. Multiple studies have found the incidence of pneumonia increases with increasing age, with persons 85 years or older having the highest incidence rate [2, 9, 10]. Another study from the US found that men aged 70 years or older had a 4.17 times higher rate of pneumonia compared with men younger than 50 years [11].

Many factors related to aging, such as comorbidities, nutritional status, and swallowing dysfunction have been found to increase the incidence of pneumonia in the older population [12]. Additionally, Jackson et al. [9] reported an increase of incidence of pneumonia in older male populations and smokers. The risk of hospitalization for pneumonia is also higher in older adults with one study finding almost 80% of those aged 80 years and older in the emergency department with pneumonia were admitted, compared with only 20% of persons between 20 and 24 years of age [13]. Vulnerable populations of older adults, like those with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), also have increased rates of hospitalization for infections, including pneumonia, after initiating oral antibiotics as an outpatient compared with persons without AD. Järvinen et al. [14] found that persons in Finland with several pre-existing somatic conditions, oral glucocorticoids use, and psychotropic use were strongly associated with hospitalization.

Several drugs are associated with an increased risk of pneumonia, including psychotropic drugs often used to treat neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, depression, pain, and insomnia in older adults [15]. Previous studies have found antipsychotics [16], benzodiazepines (BZD), and benzodiazepine-related drugs (BZRD) (e.g., zopiclone, zolpidem) [17] to be risk factors for pneumonia particularly in persons with AD. These drugs have also been studied in the context of pneumonia among older persons more often than antidepressants and antiepileptics (AED). However, the World Health Organization estimated the overall prevalence of depressive disorders in older adults at between 10 and 20%, and the prevalence varies widely between countries and cultural situations [18]. Epilepsy is the third most common neurological disease after cognitive disorder and stroke in the older population [19]. Older adults have a higher risk of new onset epilepsy compared with the general population [20], and antiepileptic drugs, such as valproate and lamotrigine, are also used in the treatment of bipolar disorder [21]. Thus, antidepressants and AEDs are commonly utilized among older adults. Some antidepressants and AEDs also have indications other than mental diseases or epilepsy, like neuropathic pain, a common ailment of the older adult population [22, 23].

Psychotropic drugs are commonly prescribed for neuropsychiatric disorders, with prevalence of use in community dwelling older adults of 19–29% [24,25,26,27]. The use is especially common in persons with cognitive disorders such as AD [28, 29]. The prevalence of cognitive disorders is increasing by age and approximately 11% of persons aged 65 years and above and 32% of those aged 85 years and above have AD [30], which makes a strong case for the need for more studies to be performed on the harms and benefits of these drugs in this vulnerable population. Most people with cognitive disorders develop at least one neuropsychiatric symptom in the course of their disease [31]. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms with psychotropics is often an off-label use, with little evidence of efficacy and effectiveness and high risk of adverse effects [32].

Adverse drug events are common in older adults and lead to over 15% of the hospital admissions in this population [33], with the rate increasing to over 30% in persons older than 75 years [34, 35]. The potential for adverse drug effects and events is higher among older adults due to more frequent comorbidities and age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes. Inappropriate prescribing is common for older people in nursing homes in Western countries [36] and a systematic review found inappropriate drug use was highly prevalent among persons with cognitive impairment [37]. Inappropriate prescribing has been defined as “the prescription of medications where risk outweighs benefit, failure to use a safer alternative drug, the misuse of a drug including incorrect dosage and duration of treatment, use of drugs with significant drug–drug interaction or drug–disease interactions and finally the omission of beneficial drugs” [38].

Clinical tools, such as the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults, are used to assist prescribers in preventing adverse drug events in older adults. This criteria, updated in 2019, comprises comprehensive lists of medications to be avoided in older adults, with one list independent of diagnosis and the other considering the diagnosis. The criteria also covers drugs to be used with caution, drug–drug interactions that should be avoided, and drugs with strong anticholinergic properties. Psychotropics, including older antipsychotics, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), have strong anticholinergic effects that can promote confusion and even delirium, as well other anticholinergic effects like urinary retention or blurring of vision [39]. These drugs are recommended to be avoided in all potentially inappropriate medication criteria for older adults.

In Europe, the equivalent clinical tool for AGS Beers criteria is the STOPP/START criteria. The second version of STOPP/START published in 2015 includes 80 STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions) criteria that represents inappropriate prescribing in older persons in day-to-day clinical practice, and 34 START (Screening Tool to Alert to Right Treatment) criteria for potential prescribing omissions. Many psychotropic drug groups (e.g., antipsychotics) and subgroups (e.g., TCAs) are listed under the STOPP criteria and are not recommended in older adults [40].

The aim of this narrative review is to summarize the findings from observational studies on the association between psychotropic drug use and risk of pneumonia in older persons. Specifically, we summarized the evidence from observational studies on the association between psychotropic drugs and the risk of pneumonia. In addition to different psychotropic drug groups (antipsychotics, BZDs and BZRDs, and antidepressants), AEDs including phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproic acid, and pregabalin are also used to treat neuropsychiatric symptoms in the aging population and therefore they were included in this review.

2 Literature Search Methods

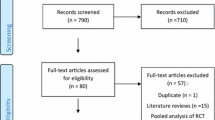

PubMed, Cochrane, and Scopus databases were searched for articles published up to August 31, 2019 using the following keywords: psychotropics, antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, antiepileptics, pneumonia, ‘older adults’ and elderly (Fig. 1). The search was restricted to publications in English. Observational studies reporting the use of psychotropic drugs in adults aged 65 years or older that contained original quantitative data regarding relative incidence of pneumonia in persons prescribed a psychotropic or AED drug were included in this review. Case reports, case series without a control group, commentaries, and reviews, along with studies that reported on the incidence of respiratory disease in general rather than pneumonia, were excluded from the review.

3 Prevalence and Indication of Psychotropics

Prescription rates of psychotropic drugs increase with age in older adults, with the highest rates found in institutionalized persons [41]. A large cohort study from the US found that 40% of persons aged 65 years or older, with a diagnosis of cognitive disorder, used a psychotropic medication (antipsychotic, antidepressant, anxiolytics) or an antiepileptic [42]. In Finland, 53% of persons with AD used psychotropic drugs compared with 33% of persons without AD [28]. Moga et al. [43] observed that older females with AD are more likely to use psychotropic drugs than older males, both in the US and Finland.

3.1 Antipsychotics

Indications for antipsychotic drugs include schizophrenia and other psychoses, bipolar disorder and as add-on treatment to antidepressants in major depressive disorders [44]. These drugs fall into two main categories: typical, also known as first-generation antipsychotics (FGA), and atypical, or second-generation antipsychotics (SGA). In addition to previously mentioned indications, antipsychotics are used in the older adult population to treat neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia [32]. In Europe, risperidone is indicated to treat agitation and aggression [45], but not in the US [46]. However, in the late 1990s in the US, more than 70% of SGA prescriptions were written for off-label indications, including neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia [47]. In 2005, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned of increased mortality in older adult patients with dementia, mostly due to cardiac or infectious causes (including pneumonia), who were treated with SGAs, and extended the warning to FGAs in 2008 [48]. Similar warnings were announced in Europe in 2008 and in Japan in 2009 [49, 50].

Antipsychotic medications are widely used in the hospital setting for non-psychiatric purposes such as management of delirium or probable delirium [51]. Recent studies found antipsychotic use in 6–9% of non-psychiatric hospitalizations, and 9–12% of those age 65 years and older [52, 53]. The prevalence of antipsychotic use is estimated to be around 4.5% of people aged over 65 years, according the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2015 [54]. Prevalence varies in older adults with dementia between countries, from 10.2% in France to 20% in Finland [28, 42, 55,56,57]. Prescription rates in the US for FGAs and SGAs declined after the FDA warnings [42], and similarly decreased in persons with dementia in the UK following the safety warnings in 2009 [58]. However, an increase in antipsychotic use for neuropsychiatric symptoms from 2005 to 2011 among newly diagnosed persons with AD was observed in Finland [28], and a similar increase was also observed in Italy in persons with dementia [58].

The AGS Beers criteria strongly recommends avoidance of antipsychotics use in older persons except in schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, or for short-term use as an antiemetic during chemotherapy. The Beers criteria also strongly recommends avoiding concomitant use of three or more central nervous system drugs [39]. The STOPP/START criteria also considers prescriptions of antipsychotic drugs to be inappropriate for persons aged 65 years and older for treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Both criteria agree that non-pharmacological treatments are the first line and antipsychotics should be avoided unless neuropsychiatric symptoms are severe [39, 40].

3.2 Benzodiazepines and Benzodiazepine-Related Drugs

BZDs and BZRDs are commonly prescribed for insomnia and anxiety to older adults [59, 60] and are one of the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medications in several countries [59, 61]. Typically, short- and medium-acting BZDs and BZRDs are prescribed for insomnia, while longer-acting BZDs are used to treat anxiety [62]. The prevalence of insomnia increases with age [63].

BZDs and BZRDs have been found to increase risk of cognitive impairment [64], delirium [65], falls [66], fractures [67, 68], and motor vehicle crashes [69] in older adults. BZRDs have similar adverse events to BZDs in older adults [70]. There is concern for adverse events in older adults, as the half-lives of BZDs are extended in this population due to age-related changes in pharmacokinetics, including alterations in drug distribution and elimination [71]. Despite the known adverse effects and events of BZDs and BZRDs, they are still commonly prescribed in the older adult population, often for long periods of time [72].

Prevalence of BZD and BZRD use in older adults is high among community dwelling older adults with a range of 4.6–25% [73,74,75,76], and with a range of 21–55% in nursing home residents [77,78,79,80,81]. However, a decline in prevalent use of BZD drugs in older adults was observed in the US (from 9.2 to 7.3%), Ontario, Canada (from 18.2 to 13.4%) and Australia (from 20.2 to 16.8%) from 2010 to 2016 [76].

The AGS Beers criteria and STOPP/START advise prescribers to avoid BZD use in older adults due to the increased sensitivity and the extended half-life of these drugs, and long-acting agents should also be avoided due to increased risk of adverse events [39, 40]. The use of these types of guidelines may be contributing to the above-mentioned decrease in BZD use [76]. The STOPP/START criteria also warn of long-term use of BZDs and BZRDs and their risk of causing withdrawal syndrome if taken for longer than 2 weeks [40]. Despite these guidelines and the adverse effects of BZD in the older adult population, incident and prevalent BZD use in older adults remain higher than in younger age groups [60, 82].

3.3 Antidepressants

The main indication for antidepressant use is treatment of depression [83], but selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are also indicated for anxiety [84, 85] and compulsive disorders [86]. In addition, TCAs, venlafaxine, and duloxetine are used to treat neuropathic pain [83, 87]. Antidepressants are the first line of pharmacological treatment for moderate to severe depression [88], but pharmacotherapy of depression in the older adult population can be challenging due to co-morbidities and concomitant medications. SSRIs are the first-line drug for depression and are better tolerated in older adults compared with TCAs [89, 90]. However, citalopram has been found to have potential risk of QT prolongation in older adults and the FDA issued warning recommendations in 2011 [91], followed by a recommended maximum dosage of citalopram of 20 mg per day for people older than 60 years of age [92]. Symptoms of depression and anxiety are some of the most common neuropsychiatric disorders in dementia.

TCAs have strong anticholinergic effects (e.g., urinary retention, dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation) and a risk of QT prolongation and cardiac arrhythmia [93]. SSRIs have also shown to have increased risk of bleeding [94]. Each group of antidepressants have their own adverse effects with varying levels of cognitive, sedation, cardiovascular (e.g., postural hypotension), and drug interactions [90, 95]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Riediger et al. [96] found sedation and anticholinergic effects, like dry mouth and sedation, to be some of the most common adverse effects of some antidepressants, like amitriptyline. The adverse effects may potentially create a risk for pneumonia in older adults [97].

Antidepressant drug use is more prevalent in older adults than in the general population, with the highest rates seen in institutionalized older people [98, 99]. Antidepressant use is more common in persons with AD compared with those without dementia [100]. The incidence of antidepressant use in older adult populations varies by country with a range of 4.7–18.6% [101].

The AGS Beers Criteria strongly recommend that TCAs should be avoided in older persons due to their strong anticholinergic properties causing adverse effects [39]. The STOPP/START criteria version 2 suggests antidepressants should be considered for moderate to severe depressive symptoms in older persons, but TCAs are inappropriate for persons with certain comorbidities (e.g., dementia, glaucoma, constipation, and cardiac conductive abnormalities) [40].

4 Prevalence and Indications of Antiepileptics

Some AEDs have been approved for indications other than epilepsy, such as neuropathic pain [22, 102], and are also used for off-label treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia [103, 104]. However, a recent Cochrane Database System Review found valproate use to be ineffective for management of agitation in dementia and may lead to an increased risk of adverse effects [105]. Most AEDs, and especially older ones, have been found to have sedative effects [106, 107] among older persons, increasing the risk of aspiration [108], which in turn may lead to increased risk of pneumonia.

The prevalence of AED use has been increasing in Europe, North America, and Australia [109,110,111,112,113,114], most likely due to indications other than epilepsy [112, 114]. Studies from Europe have reported AED use to be 3.2–5% in the older population (> 60 years of age) [22, 115], while higher rates of AED use (ranging from 7.7 to 14.3%) have been found among nursing home residents in the US [116,117,118,119]. AED use in older persons has increased in the recent past due to the indication for treatment of neuropathic pain and neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia with AEDs [17, 22].

The AGS Beers criteria recommends AEDs be avoided in older adults, except for seizure and mood disorders. Concomitant use of three or more central nervous system agents, including AEDs, should be avoided to decrease the risk of falls [39]. There are no recommendations in regard to AEDs in the STOPP/START criteria [40].

5 Psychotropic Use and Risk of Pneumonia

We identified only one study that looked at psychotropic drug use in general and the risk of fatal versus non-fatal pneumonia. This recent study by Ishii et al. [120] found that Japan had a similar rate of psychotropic drug use in fatal cases of pneumonia to that of the survivors, 33.5% and 35%, respectively. Varying amounts of research has been done on the specific groups of psychotropic drugs and the association with pneumonia, with most of the research focused on antipsychotics.

5.1 Antipsychotics

A recent systematic review by Dzahini et al. [121] included 19 observational studies and investigated the association of antipsychotic exposure to the incidence of pneumonia. They found the risk of pneumonia increased with both FGAs and SGAs. Studies in that review were not limited to the older adult population, but only two studies assessed only persons < 65 years of age. Three additional observational studies have been published after the review search dates, with mixed findings (Table 1). Herzig et al. [122] found a significant association between antipsychotic exposure and aspiration pneumonia compared with unexposed persons in non-psychiatric hospitalized patients in a large cohort study from the US. The study population was not limited to those aged 65 years and higher, but the subgroup analysis (< 65, 65–74, and ≥ 75 years) found higher risk of pneumonia with increased age [122]. However, Kim et al. [123] found older persons (mean age 70 years) who had undergone cardiac surgery and administered FGAs versus SGAs after surgery had similar rates of pneumonia and a secondary analysis did not find meaningful variation by age category (< 65, 65–74, and ≥ 75 years). The study population of Tolppanen et al. [16] included persons with and without AD, the most common form of cognitive disorder, with an average age of the cohorts near 80 years. This study reported an increased risk of hospitalization for pneumonia for new antipsychotic use in persons with and without AD compared with non-users, with higher risk of pneumonia seen in persons without AD [16].

Hwang et al. [124] found SGA use versus non-use was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for pneumonia within the first 90 days of SGA initiation in persons 65 years or older. Pneumonia was used as a secondary outcome in this study and may have been overlooked during the systematic review search. Similarly, Hennessy et al. [125] also found an increased risk of hospitalization for pneumonia with antipsychotic use compared with non-users in persons 65 years or older, but antidepressants were the primary drug exposure in the study.

5.2 Benzodiazepine and Benzodiazepine-Related Drugs

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Sun et al. [126] included eight studies with an older adult study population and found the odds for developing pneumonia in those 65 years or older were 1.29-fold higher in BZD or BZRD users compared with non-users. This relative risk increase was higher than that observed in the general population, but a subgroup analysis found persons aged < 65 years (4 studies included) had a higher risk of pneumonia [odds ratio (OR) 1.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.39–2.34] compared with persons aged 65 years or older. This review only included studies that compared pneumonia development among people receiving BZDs or BZRDs versus those with no treatment and had high heterogeneity (I2 = 93.6%) [126].

In three case–control studies, persons with a diagnosis of pneumonia were significantly more likely (OR 1.31–9.3) to have been current users of BZD drugs than those without a pneumonia diagnosis [125, 127, 128] (Table 2). Several study populations were limited to persons with common chronic conditions of older persons, such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), chronic kidney disease (CKD) and AD. The study population in Wang et al. [128] was persons with CKD and the mean age was 80 years. There was an increased risk of pneumonia with current BZD use, but not with current BZRD use compared with non-users [128]. Hennessy et al. [125] found and increased risk of pneumonia in persons 65 years or older who were BZD users compared with non-users. The Chung et al. [127] study population had a mean age > 65 years and was limited to persons with COPD. Both current BZD and BZRD users have an increased risk of pneumonia compared with non-users [127]. The Vozoris et al. [129] study population also included persons > 65 years with COPD and was suggestive of an increased risk of hospitalization for pneumonia or COPD in BZD users compared with non-users, but the confidence intervals were wide and included 1. Among community dwelling adults with AD (mean age 80 years) Taipale et al. [17] found an increased risk of hospitalization or death due to pneumonia with BZD use, but there was no difference in risk for BZRD users compared with non-users. The greatest risk was within 30 days after the initiation of BZDs [17]. Huybrechts et al. [130] found when comparing new users of BZDs (within 180 days before pneumonia diagnosis) with new users of an SGA, BZD users had a decreased risk of pneumonia in person aged 65 years or older, but it was not statistically significant.

5.3 Antidepressants

Three studies have reported inconsistent findings on the association between antidepressant use and pneumonia (Table 3). Vozoris et al. [131] found that new users of SSRIs or SNRIs in a population of persons aged 65 years or more with COPD had higher rates of hospitalization for COPD or pneumonia than non-users. Hennessy et al. [125] reported an increased risk of hospitalization for pneumonia in persons aged 65 years or more with minimal adjustment of covariates (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.46–1.78) with any antidepressant use compared with non-users, but when further adjusted for comorbidities the association was nullified. Huybrechts et al. [130] studied persons admitted to a nursing home who were aged 65 years or more, and found persons who initiated antidepressants had an increased risk for pneumonia compared with initiators of SGAs, but the findings were not statistically significant [130].

5.4 Antiepileptics

Studies regarding AED use and risk of pneumonia in older persons are lacking, and only one study was identified (Table 4). The study by Taipale et al. [23] used a population of community dwellers with AD, with a mean age of 80 years, and reported that AED use was associated with a twofold increase in risk of hospitalization or death due to pneumonia compared with non-use. The risk was highest during the first 30 days of AED use, but continued to be elevated after 2 years. Certain AEDs were found to be associated with an increased risk of pneumonia, including valproic acid, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and pregabalin [23].

6 Possible Mechanisms for the Association of Psychotropic and Antiepileptic Drugs and Pneumonia

Psychotropic and antiepileptic drugs have sedative effects and might cause discoordination in swallowing [132] and thus increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia.

6.1 Antipsychotics

There are multifactorial pathways in which antipsychotics can lead to pneumonia. Antipsychotics affect dopamine D2, cholinergic, and histamine-1 receptors, which can lead to extrapyramidal adverse effects, dysphagia, and sedation [133,134,135]. Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) are more common with FGAs than SGAs and these symptoms may impair swallowing. The most important EPS linked to pneumonia risk is tardive dyskinesia, which is characterized by involuntary buccolingual movements [136]. Further, according to a previous systematic review, both FGAs and SGAs are associated with oropharyngeal dysphagia [137]. Antipsychotics cause sedative effects by blocking histamine-1 receptors [138]. Together with age-related changes in pulmonary secretion, these sedative effects may make it difficult to manage secretions and so increase the risk of pneumonia [132]. Further, anticholinergic effects cause xerostomia and so impair oropharyngeal bolus transport [132, 135]. Antipsychotic drugs have also been suggested to have direct or indirect effects on the immune system, which can lead to increased risk of infections, including pneumonia [139].

6.2 Benzodiazepines and Benzodiazepine-Related Drugs

Older persons are at an increased risk of BZD-induced sedation, potentially leading to an increased risk of aspiration pneumonia [140]. The sedative effects may be more pronounced in older adults because of age-related pharmacodynamic changes [141]. The use of BZDs has also been associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in older persons and this may be related to relaxation of the esophageal sphincter, potentially causing aspiration [132]. Some animal studies have suggested that BZDs increase the susceptibility to infection by activation of certain GABA receptors on immune cells, but more research is needed on humans [142].

6.3 Antidepressants

Each class of antidepressants has its own adverse effects. Anticholinergic properties, strongest in TCAs, cause effects such as dry mouth [143], potentially creating a risk for pneumonia in older adults [97]. Similar to other psychotropic drugs, some antidepressants have sedative effects [95]. The antihistaminergic effects of TCAs and a few other antidepressants like mirtazapine, mianserin, or trazodone cause sedation, while moclobemide causes sedation by the inhibition of the monoamine oxidase enzyme [144]. Moreover, it has been estimated that 10–20% of SSRI and SNRI users experience adverse effects of fatigue and sleepiness [145,146,147,148,149]. Nausea and vomiting are common adverse effects of SSRI and SNRI drugs, a potential risk factor for aspiration pneumonia [150]. SSRI and SNRI drugs may also have immunosuppressant effects, increasing the risk of infections [151,152,153,154].

6.4 Antiepileptics

Adverse effects of AED drugs on the immune system have been reported. Several different mechanisms affecting cytokines as well as humoral and cellular immunity effect hypersensitivity or immune suppression with AED use [155]. Another adverse effect of several AED drugs is sedation [108]. The sedative AEDs, including phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproic acid, were associated with an increased risk of pneumonia in the Finnish study, perhaps by increasing the risk of aspiration [17, 106, 107].

7 Therapeutic and Clinical Implications

Older adults have been underrepresented in randomized controlled trials due to comorbidities and other exclusion criteria [156]. Therefore, observational studies are often used to create clinical care guidelines and assist in directing clinical practice. These care guidelines should also be revised when the evidence base develops. Due to the high rate of comorbidities, polypharmacy, communication issues, and non-compliance in the older adult population, prescribers are faced with a difficult task of balancing the benefits and the adverse effects of medications.

Even though the AGS Beers criteria and the STOPP/START criteria do not directly recommend psychotropic drugs be avoided due to the risk of pneumonia, they do list avoidance or for these drugs to be used with caution due to the well documented adverse effects (e.g., sedation) leading to adverse events (e.g., falls), but these same adverse effects could also increase the risk of pneumonia.

Assessment of medication on a regular basis as a part of clinical examination is necessary to reduce the risk of respiratory adverse events in the older population and may also aid in eliminating duplication of therapies and identify potential drug–drug interactions [157]. Although reducing polypharmacy may lower the risk of pneumonia, it is important to focus on specific drugs and drugs groups, their indications, and the risk–benefit profile. Thus, the aim of medication assessments should always be the benefit of the patient, not necessarily the number of drugs.

A multidisciplinary approach in the care of older persons has been shown to have positive outcomes in improving the quality of pharmacotherapy [158]. A multidisciplinary team including clinical pharmacists, clinicians, and other healthcare professionals can review medication lists and alert the prescriber to concerns regarding the use psychotropics and AEDs in the older aged person, and inform the user or caregivers of signs and symptoms, such as swallowing or respiratory issues, to be aware of.

8 Discussion

The association between psychotropic drugs and pneumonia in older adults varies between drug groups, and some individual drugs, with the majority of research focusing on antipsychotics and BZDs. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses found increased risk of pneumonia associated with antipsychotic [121] and BZD [126] use, but were not specifically focused on the older adult population. Recent studies focusing on the older and potentially more vulnerable population have supported the findings of these systematic reviews. Although cognitive disorders and use of psychotropic drugs are more common among old adults, only a few studies have assessed the association of antipsychotics, BZDs, and BZRDs and pneumonia in this specific group [16, 17]. Minimal studies and inconsistent evidence between antidepressants and their association with pneumonia in older adults was found. Also, an association between AEDs and pneumonia was seen in older adults [18], but the evidence is limited to one study with conflicting results compared with a general population study [159]. Currently there are no studies on specific drug substances as the current research has focused on different drug groups.

This topic is therefore worthy of further investigation. The rate of psychotropic drug use in older adults is high, despite recommendations on avoiding potential inappropriate medications. Risk of hospitalization and death from pneumonia are high in those aged 65 years and over [160], along with the healthcare costs [161]. Identifying risk factors, including pharmacotherapy, and implementing strategies for reducing exposure to modifiable conditions may decrease mortality and morbidity. Herzig et al. [122] suggested that there are more than 4000 excess cases of aspiration pneumonia attributable to hospital antipsychotic use each year in the US. The systematic review by Dzahini et al. [121] calculated the number needed to harm to be 86 in persons aged 65 years or older based on an incidence of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in a study from Spain [162]. Sun et al. [126] found a small increase in risk of pneumonia with BZD or BZRD use in their meta-analysis, but the impact on a population level of BZD- or BZRD-associated pneumonia may be substantial given the large number of users. To better treat and reduce adverse drug events, including pneumonia, in this growing older population, prescribers need to be informed of the risk of psychotropic drug use.

Off-label drug use of psychotropics are common in persons with dementia [16], and the risks of use may outweigh the benefits. Neuropsychiatric symptoms mostly comprise agitation, mood disorders, disinhibited behavior, psychotic symptoms, impairment of the sleep and wake cycle, wandering, perseveration, and inappropriate collecting or shouting [90]. However, low-dose risperidone has been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) only for persistent aggression in patients with moderate to severe AD [45], but this indication is not accepted by the US FDA [46]. The FDA warning actually led to a decrease in antipsychotic use in persons with dementia in the US [42], but another study found an increase in prescriptions for BZDs and BZRDs to older persons with dementia following the warnings by the FDA [163]. This suggested that instead of using antipsychotics, the prescribing moved to off-label use of BZDs to manage the neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Existing criteria like the AGS Beers criteria have been shown to reduce the number of potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions and should be utilized in medical providers’ prescribing practices [164]. The AGS Beers criteria has been shown to be more successful at identifying potentially inappropriate medications in the US, Australia, and Taiwan compared with European studies [165,166,167,168]. This can possibly be explained by the fact that several drugs included in the Beers Criteria are rarely prescribed or do not appear in the drug formularies in Europe [169, 170]. The STOPP/START criteria was developed in Europe [40] and several country-specific and region-specific derivations of the criteria have recently been developed, such as the EU(7)-PIM list [171], Meds75 + used in Finland [172], and the NORGEP used in Norway [173]. The AGS Beers criteria does not specifically comment on the association between psychotropics and pneumonia, but does list several groups of psychotropics on the strong anticholinergic properties table, and anticholinergic drugs are a known risk factor for pneumonia in older adults [39, 97].

The Beers, STOPP/START, or criteria derived from them also do not report pneumonia as a risk of psychotropic use, but the evidence on antipsychotics and BZDs and BZRDs should be taken into consideration with the next update of the criteria. Additionally, more research needs to be done on all the groups of psychotropic drugs and antiepileptic drugs, especially in populations that have high prevalence of use such as persons with cognitive disorders.

Psychotropic use is common in older adults, and these drugs are at least partly inappropriately used in this population with high risk of adverse drug events including pneumonia. A meta-analysis by Nosè et al. 2015, reported similar risk of pneumonia with antipsychotic use in persons aged < 65 years (two studies) and persons aged 65 years or more (four studies) [134]. The incidence of hospitalization for CAP increases with age [174] and may be in addition to age-related changes in the respiratory system, partly associated with the high prevalence of antipsychotic use in older adults. BZD and BZRD use have been found to be associated with increased risk of pneumonia in older vulnerable populations [126].

There is a lack of knowledge about the use of antidepressants and the association with pneumonia in older adults as there were only three studies concerning the topic. Further studies need to focus on subgroups of antidepressants because TCAs, SSRIs, SNRIs, and others like mirtazapine and mianserin might have different effects on risk of pneumonia. More research is also needed to clarify the association between AED use and pneumonia. Only one study conducted among persons with Alzheimer’s disease was restricted to the older population [18]. The association between AED use and pneumonia observed in that study was not evident in a previous study focusing on an adult population of persons (mean age 44 years) with bipolar disorder [159].

Taken together, these findings, as well as the Beers and STOPP/START criteria, underline the importance of weighing the risks and benefits of using these drugs. The on- and off-label indications of these drugs are common, and especially so in aged populations. The prevalence of mental health disorders have increased by about 16% between 2005 and 2015 and are expected to continue to increase with the aging population in many countries [175]. It was estimated in 2010 that the prevalence of persons with neuropsychiatric disorders in the European Union population was 38.2% [176]. These conditions should be treated, as depression and depression-like symptoms, for example, can lead to impaired functioning in daily life and have greater effects on activities of daily living compared with other chronic medical conditions such as COPD, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases [177]. However, older adults, both community dwelling and institutionalized, are often prescribed antidepressants with no documented indication [178], potentially leading to inappropriate prescribing and increasing the risk of adverse events. In addition, non-pharmacologic treatments should be first line for neuropsychiatric symptoms and antipsychotics could be prescribed only for the most severe symptoms, if the symptoms cause serious risk of harm to the patient or others [32, 103, 179, 180]. Thus, overall, there should be a high threshold for prescribing these drugs.

Observational studies are prone to confounding and thus the association between these drugs and pneumonia may be partially explained by confounding. All studies referred to in the review adjusted for covariates when reporting results, but it is possible that residual confounding still exists. Most studies did not report the indication for medication use, which could lead to confounding by indication.

9 Conclusion

Antipsychotics, BZDs, and BZRDs are associated with higher risk of pneumonia. More studies are needed because there is gap in knowledge concerning risk of pneumonia among users of antidepressants and AEDs as well as risks in the most vulnerable older population, persons with cognitive disorders. Clinical tools such as the Beers and STOPP/START criteria advocate against using these drugs for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia among older adults. Use of these guidelines may reduce adverse drug events such as pneumonia. Higher thresholds for prescribing psychotropics and AEDs are needed for older vulnerable persons with risk of pneumonia.

References

Marrie TJ, File TM. Bacterial pneumonia in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:459–77.

Fry AM, Shay DK, Holman RC, Curns AT, Anderson LJ. Trends in hospitalizations for pneumonia among persons aged 65 years or older in the United States, 1988–2002. JAMA. 2005;294:2712–9.

Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep-US Dep Health Hum Serv. 2019;68:1–77.

Curns AT, Holman RC, Sejvar JJ, Owings MF, Schonberger LB. Infectious disease hospitalizations among older adults in the United States from 1990 through 2002. JAMA Intern Med. 2005;165:2514–20.

Centers for Disease Control. QuickStats: rate* of hospitalization for pneumonia, by age group—National Hospital Discharge Survey, United States, 2000–2010. 2012.

Van Gageldonk-Lafeber AB, Bogaerts MAH, Verheij RA, Van Der Sande MAB. Time trends in primary-care morbidity, hospitalization and mortality due to pneumonia. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:1472–8.

Trotter CL, Stuart JM, George R, Miller E. Increasing hospital admissions for pneumonia, England. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:727–33.

Søgaard M, Nielsen RB, Schønheyder HC, Nørgaard M, Thomsen RW. Nationwide trends in pneumonia hospitalization rates and mortality, Denmark 1997–2011. Respir Med. 2014;108:1214–22.

Jackson ML, Neuzil KM, Thompson WW, Shay DK, Yu O, Hanson CA, et al. The burden of community-acquired pneumonia in seniors: results of a population-based study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1642–50.

Ochoa-Gondar O, Vila-Córcoles A, de Diego C, Arija V, Maxenchs M, Grive M, et al. The burden of community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: the Spanish EVAN-65 Study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:222.

Baik I, Curhan GC, Rimm EB, Bendich A, Willett WC, Fawzi WW. A prospective study of age and lifestyle factors in relation to community-acquired pneumonia in US men and women. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3082–8.

Henig O, Kaye KS. Bacterial Pneumonia in Older Adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31:689–713.

Marrie TJ, Huang JQ. Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia in Edmonton, Alberta: an emergency department-based study. Can Respir J. 2005;12:139–42.

Järvinen H, Taipale H, Koponen M, Tanskanen A, Tiihonen J, Tolppanen A-M, et al. Hospitalization after oral antibiotic initiation in finnish community dwellers with and without Alzheimer’s disease: retrospective register-based cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:437–45.

Liapikou A, Cilloniz C, Torres A. Drugs that increase the risk of community-acquired pneumonia: a narrative review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17:991–1003.

Tolppanen A-M, Koponen M, Tanskanen A, Lavikainen P, Sund R, Tiihonen J, et al. Antipsychotic use and risk of hospitalization or death due to pneumonia in persons with and those without alzheimer disease. Chest. 2016;150:1233–41.

Taipale H, Tolppanen A-M, Koponen M, Tanskanen A, Lavikainen P, Sund R, et al. Risk of pneumonia associated with incident benzodiazepine use among community-dwelling adults with Alzheimer disease. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Med Can. 2017;189:E519–29.

World Health Organization. The world health report 2001: Mental health: new understanding. New Hope: World Health Organization; 2001.

World Health Organization. Neurological disorders: public health challenges. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

Stefan H. Epilepsy in the elderly: facts and challenges. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124:223–37.

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 2]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185/chapter/1-Recommendations#care-for-adults-children-and-young-people-across-all-phases-of-bipolar-disorder-2.

Baftiu A, Feet SA, Larsson PG, Burns ML, Henning O, Sætre E, et al. Utilisation and polypharmacy aspects of antiepileptic drugs in elderly versus younger patients with epilepsy: a pharmacoepidemiological study of CNS-active drugs in Norway, 2004–2015. Epilepsy Res. 2018;139:35–42.

Taipale H, Lampela P, Koponen M, Tanskanen A, Tiihonen J, Hartikainen S, et al. Antiepileptic drug use is associated with an increased risk of pneumonia among community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease-matched cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;68:127–36.

Aparasu RR, Mort JR, Brandt H. Psychotropic prescription use by community-dwelling elderly in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:671–7.

Linjakumpu T, Hartikainen S, Klaukka T, Koponen H, Kivelä S-L, Isoaho R. Psychotropics among the home-dwelling elderly—increasing trends. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:874–83.

Voyer P, Cohen D, Lauzon S, Collin J. Factors associated with psychotropic drug use among community-dwelling older persons: a review of empirical studies. BMC Nurs. 2004;3:3.

Téllez-Lapeira J, López-Torres Hidalgo J, García-Agua Soler N, Gálvez-Alcaraz L, Escobar-Rabadán F, García-Ruiz A. Prevalence of psychotropic medication use and associated factors in the elderly. Eur J Psychiatry. 2016;30:183–94.

Taipale H, Koponen M, Tanskanen A, Tolppanen A-M, Tiihonen J, Hartikainen S. High prevalence of psychotropic drug use among persons with and without Alzheimer׳s disease in Finnish nationwide cohort. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:1729–37.

Gustafsson M, Karlsson S, Gustafson Y, Lövheim H. Psychotropic drug use among people with dementia–a six-month follow-up study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;14:56.

Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;2016(12):459–509.

Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288:1475–83.

Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Eyler AE, Hilty DM, Horvitz-Lennon M, Jibson MD, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:543–6.

Beijer HJM, de Blaey CJ. Hospitalisations caused by adverse drug reactions (ADR): a meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharm World Sci PWS. 2002;24:46–54.

Chan M, Nicklason F, Vial JH. Adverse drug events as a cause of hospital admission in the elderly. Intern Med J. 2001;31:199–205.

Page RL, Mark RJ. The risk of adverse drug events and hospital-related morbidity and mortality among older adults with potentially inappropriate medication use. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:297–305.

Morin L, Laroche M-L, Texier G, Johnell K. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults living in nursing homes: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:862.e1–9.

Johnell K. Inappropriate drug use in people with cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2015;10:178–84.

Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, Hughes C, Lapane KL, Swine C, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet Lond Engl. 2007;370:173–84.

2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;2019(67):674–94.

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44:213–8.

Maguire A, Hughes C, Cardwell C, O’Reilly D. Psychotropic medications and the transition into care: a national data linkage study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:215–21.

Kales HC, Zivin K, Kim HM, Valenstein M, Chiang C, Ignacio RV, et al. Trends in antipsychotic use in dementia 1999–2007. JAMA Psychiatry. 2011;68:190–7.

Moga DC, Taipale H, Tolppanen A-M, Tanskanen A, Tiihonen J, Hartikainen S, et al. A comparison of sex differences in psychotropic medication use in older people with Alzheimer’s disease in the US and Finland. Drugs Aging. 2017;34:55–65.

Scheurer D. Antipsychotic medications in primary care: Limited benefit, sizeable risk [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Aug 1]. Available from: https://docplayer.net/10751123-Antipsychotic-medications-in-primary-care.html.

European Medicines Agency. Risperdal [Internet]. Eur. Med. Agency. 2018 [cited 2019 Sep 9]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/risperdal.

Food and Drug Administration. Label for Risperdal [Internet]. [cited 2019 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/020272s056,020588s044,021346s033,021444s03lbl.pdf.

Glick ID, Murray SR, Vasudevan P, Marder SR, Hu RJ. Treatment with atypical antipsychotics: new indications and new populations. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35:187–91.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Postmarket drug safety information for patients and providers: information on conventional antipsychotics [Internet]. Inf. Conv. Antipsychotics. 2008 [cited 2019 Jul 31]. Available from: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170722033234/https:/www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm107211.htm.

Pharmaceutical and Food Safety Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. MHLW Pharmaceuticals and medical devices safety information (FY2009) [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000153593.pdf.

European Medicines Agency. CHMP assessment report on conventional antipsychotics. Procedure under Article 5(3) of Regulation (EC) No. 726/2004. [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2010/01/WC500054057.pdf.

Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Guess JR, Gurwitz JH, Marcantonio ER. Antipsychotic medication utilization in nonpsychiatric hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:543–9.

Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Guess JR, Stevens JP, Marshall J, Gurwitz JH, et al. Antipsychotic use in hospitalized adults: rates, indications, and predictors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:299–305.

Loh KP, Ramdass S, Garb JL, Brennan MJ, Lindenauer PK, Lagu T. From hospital to community: use of antipsychotics in hospitalized elders. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:802–4.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. People with a prescription of antipsychotics, 2015 or nearest year [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2017/people-with-a-prescription-of-antipsychotics-2015-or-nearest-year_health_glance-2017-graph198-en.

Kuroda N, Hamada S, Sakata N, Jeon B, Iijima K, Yoshie S, et al. Antipsychotic use and related factors among people with dementia aged 75 years or older in Japan: a comprehensive population-based estimation using medical and long-term care data. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:472–9.

Martinez C, Jones RW, Rietbrock S. Trends in the prevalence of antipsychotic drug use among patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias including those treated with antidementia drugs in the community in the UK: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002080.

Gallini A, Andrieu S, Donohue JM, Oumouhou N, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Gardette V. Trends in use of antipsychotics in elderly patients with dementia: impact of national safety warnings. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol J Eur Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:95–104.

Sultana J, Fontana A, Giorgianni F, Pasqua A, Cricelli C, Spina E, et al. The effect of safety warnings on antipsychotic drug prescribing in elderly persons with dementia in the United Kingdom and Italy: a population-based study. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:1097–109.

Lader M. Benzodiazepines revisited—will we ever learn? Addiction. 2011;106:2086–109.

Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:136–42.

López-Muñoz F, Álamo C, García-García P. The discovery of chlordiazepoxide and the clinical introduction of benzodiazepines: half a century of anxiolytic drugs. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:554–62.

Ashton H. Guidelines for the rational use of benzodiazepines. Drugs. 1994;48:25–40.

Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep and its disorders in aging populations. Art Good Sleep Proc 6th Int Sleep Disord Forum Sleep Soc. 2009;10:7–11.

Islam MM, Iqbal U, Walther B, Atique S, Dubey NK, Nguyen P-A, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia in the elderly population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2016;47:181–91.

Clegg A, Young JB. Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010;40:23–9.

Díaz-Gutiérrez MJ, Martínez-Cengotitabengoa M, Sáez de Adana E, Cano AI, Martínez-Cengotitabengoa MT, Besga A, et al. Relationship between the use of benzodiazepines and falls in older adults: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2017;101:17–22.

Saarelainen L, Tolppanen A-M, Koponen M, Tanskanen A, Sund R, Tiihonen J, et al. Risk of hip fracture in benzodiazepine users with and without Alzheimer disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:87.e15–21.

Donnelly K, Bracchi R, Hewitt J, Routledge PA, Carter B. Benzodiazepines, Z-drugs and the risk of hip fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174730.

Hemmelgarn B, Suissa S, Huang A, Jean-Francois B, Pinard G. Benzodiazepine use and the risk of motor vehicle crash in the elderly. JAMA. 1997;278:27–31.

Brandt J, Leong C. Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs: an updated review of major adverse outcomes reported on in epidemiologic research. Drugs RD. 2017;17:493–507.

Ruscin JM, Linnebur SA. Pharmacokinetics in Older Adults [Internet]. MSD Manual Professinal Edition; 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/geriatrics/drug-therapy-in-older-adults/pharmacokinetics-in-older-adults.

Picton JD, Marino AB, Nealy KL. Benzodiazepine use and cognitive decline in the elderly. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:e6–12.

Béland S-G, Préville M, Dubois M-F, Lorrain D, Grenier S, Voyer P, et al. Benzodiazepine use and quality of sleep in the community-dwelling elderly population. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:843–50.

Dublin S, Walker RL, Jackson ML, Nelson JC, Weiss NS, Von Korff M, et al. Use of opioids or benzodiazepines and risk of pneumonia in older adults: a population-based case-control study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1899–907.

Petrov ME, Sawyer P, Kennedy R, Bradley LA, Allman RM. Benzodiazepine (BZD) use in community-dwelling older adults: longitudinal associations with mobility, functioning, and pain. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59:331–7.

Brett J, Maust DT, Bouck Z, Ignacio RV, Mecredy G, Kerr EA, et al. Benzodiazepine use in older adults in the United States, Ontario, and Australia from 2010 to 2016. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1180–5.

Ster MP, Gorup EC. Psychotropic medication use among elderly nursing home residents in Slovenia: cross-sectional study. Croat Med J. 2011;52:16–24.

Azermai M, Elseviers M, Petrovic M, Van Bortel L, Stichele RV. Geriatric drug utilisation of psychotropics in Belgian nursing homes. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2011;26:12–20.

Bourgeois J, Elseviers MM, Azermai M, Van Bortel L, Petrovic M, Vander Stichele RR. Benzodiazepine use in Belgian nursing homes: a closer look into indications and dosages. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:833–44.

Gobert M, D’hoore W. Prevalence of psychotropic drug use in nursing homes for the aged in Quebec and in the French-speaking area of Switzerland. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:712–21.

Hosia-Randell H, Pitkälä K. Use of psychotropic drugs in elderly nursing home residents with and without dementia in Helsinki, Finland. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:793–800.

Maust DT, Kales HC, Wiechers IR, Blow FC, Olfson M. No end in sight: benzodiazepine use in older adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:2546–53.

Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant Use Among Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2001–2014 [Internet]. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017 Aug. Report No.: 283. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db283.htm.

Gardarsdottir H, Heerdink ER, van Dijk L, Egberts ACG. Indications for antidepressant drug prescribing in general practice in the Netherlands. J Affect Disord. 2007;98:109–15.

Instituite for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Treatment options for generalized anxiety disorder [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: InformedHealth.org; 2017 [cited 2019 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279594/.

Pittenger C, Kelmendi B, Bloch M, Krystal JH, Coric V. Clinical treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Edgmont Pa Townsh. 2005;2:34–43.

Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Pain, pain, go away: antidepressants and pain management. Psychiatry Edgmont Pa Townsh. 2008;5:16–9.

American Psychological Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Depression Across Three Age Cohorts [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline/guideline.pdf.

Mottram PG, Wilson K, Strobl JJ. Antidepressants for depressed elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;1–58.

Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S. Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry- 12th Edition [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/35716429/Prescribing_Guidelines_in_Psychiatry_12TH_EDITION.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Abnormal heart rhythms associated with high doses of Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide) [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-abnormal-heart-rhythms-associated-high-doses-celexa-citalopram.

Food and Drug Administration. Clarification of dosing and warning recommendations for Celexa [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/special-features/clarification-dosing-and-warning-recommendations-celexa.

Riedel WJ, van Praag HM. Avoiding and managing anticholinergic effects of antidepressants. CNS Drugs. 1995;3:245–59.

Paton C, Ferrier IN. SSRIs and gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ. 2005;331:529–30.

Comaty J. Geriatric pharmacotherapy. Am Soc Adv Pharmacother [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Jun 14]; Available from: https://www.apadivisions.org/division-55/publications/tablet/2015/12/geriatric-medicine.

Riediger C, Schuster T, Barlinn K, Maier S, Weitz J, Siepmann T. Adverse Effects of Antidepressants for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Front Neurol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Jul 29];8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2017.00307/full.

Chatterjee S, Carnahan RM, Chen H, Holmes HM, Johnson ML, Aparasu RR. Anticholinergic medication use and risk of pneumonia in elderly adults: a nested case–control study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:394–400.

Bourgeois J, Elseviers MM, Van Bortel L, Petrovic M, Vander Stichele RH. The use of antidepressants in Belgian nursing homes. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:759–69.

Kramer D, Allgaier A-K, Fejtkova S, Mergl R, Hegerl U. Depression in nursing homes: prevalence, recognition, and treatment. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2009;39:345–58.

Puranen A, Taipale H, Koponen M, Tanskanen A, Tolppanen A-M, Tiihonen J, et al. Incidence of antidepressant use in community-dwelling persons with and without Alzheimer’s disease: 13-year follow-up. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32:94–101.

Tamblyn R, Bates DW, Buckeridge DL, Dixon W, Forster AJ, Girard N, et al. Multinational comparison of new antidepressant use in older adults: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027663.

Cruccu G, Truini A. A review of neuropathic pain: from guidelines to clinical practice. Pain Ther. 2017;6:35–42.

Finnish Medical Society Duodecim. Finnish Current Care Guidlines for Memory Disorders [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 May 3]. Available from: http://www.kaypahoito.fi.

Masopust J, Protopopova D, Valis M, Pavelek Z, Klimova B. Treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementias with psychopharmaceuticals: A review. 2018.

Baillon SF, Narayana U, Luxenberg JS, Clifton AV. Valproate preparations for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jul 22]; Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003945.pub4/full.

Park S-P, Kwon S-H. Cognitive effects of antiepileptic drugs. J Clin Neurol Seoul Korea. 2008;4:99–106.

Eddy CM, Rickards HE, Cavanna AE. The cognitive impact of antiepileptic drugs. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2011;4:385–407.

Loeb M, McGeer A, McArthur M, Walter S, Simor AE. Risk factors for pneumonia and other lower respiratory tract infections in elderly residents of long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2058–64.

Landmark CJ, Larsson PG, Rytter E, Johannessen SI. Antiepileptic drugs in epilepsy and other disorders—a population-based study of prescriptions. Epilepsy Res. 2009;87:31–9.

Savica R, Beghi E, Mazzaglia G, Innocenti F, Brignoli O, Cricelli C, et al. Prescribing patterns of antiepileptic drugs in Italy: a nationwide population-based study in the years 2000–2005. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:1317–21.

Alacqua M, Trifirò G, Spina E, Moretti S, Tari DU, Bramanti P, et al. Newer and older antiepileptic drug use in Southern Italy: a population-based study during the years 2003–2005. Epilepsy Res. 2009;85:107–13.

Hollingworth SA, Eadie MJ. Antiepileptic drugs in Australia: 2002–2007. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:82–9.

Berlowitz DR, Pugh MJV. Pharmacoepidemiology in Community‐Dwelling Elderly Taking Antiepileptic Drugs. Int Rev Neurobiol [Internet]. Academic Press; 2007 [cited 2019 Jul 22]. p. 153–63. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0074774206810093.

Tsiropoulos I, Gichangi A, Andersen M, Bjerrum L, Gaist D, Hallas J. Trends in utilization of antiepileptic drugs in Denmark. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;113:405–11.

Sarycheva T, Taipale H, Lavikainen P, Tiihonen J, Tanskanen A, Hartikainen S, et al. Incidence and prevalence of antiepileptic medication use in community-dwelling persons with and without Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66:387–95.

Garrard J, Harms S, Hardie N, Eberly LE, Nitz N, Bland P, et al. Antiepileptic drug use in nursing home admissions. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:75–85.

Garrard J, Cloyd J, Gross C, Hardie N, Thomas L, Lackner T, et al. Factors associated with antiepileptic drug use among elderly nursing home residents. J Gerontol Ser A. 2000;55:M384–92.

Bathena SPR, Leppik IE, Kanner AM, Birnbaum AK. Antiseizure, antidepressant, and antipsychotic medication prescribing in elderly nursing home residents. Epilepsy Behav EB. 2017;69:116–20.

Huying F, Klimpe S, Werhahn KJ. Antiepileptic drug use in nursing home residents: a cross-sectional, regional study. Seizure Eur J Epilepsy. 2006;15:194–7.

Ishii H, Kushima H, Kinoshita Y, Matsumoto T, Watanabe K, Fujita M. The limited impact of psychiatric disease and psychotropic medication on the outcome of hospitalization for pneumonia. J Infect Chemother Off J Jpn Soc Chemother. 2018;24:1009–12.

Dzahini O, Singh N, Taylor D, Haddad P. Antipsychotic drug use and pneumonia: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf). 2018;32:1167–81.

Herzig SJ, LaSalvia MT, Naidus E, Rothberg MB, Zhou W, Gurwitz JH, et al. Antipsychotics and the risk of aspiration pneumonia in individuals hospitalized for nonpsychiatric conditions: a cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:2580–6.

Kim DH, Huybrechts KF, Patorno E, Marcantonio ER, Park Y, Levin R, et al. Adverse events associated with antipsychotic use in hospitalized older adults after cardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1229–37.

Hwang YJ, Dixon SN, Reiss JP, Wald R, Parikh CR, Gandhi S, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk for acute kidney injury and other adverse outcomes in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:242–8.

Hennessy S, Bilker WB, Leonard CE, Chittams J, Palumbo CM, Karlawish JH, et al. Observed association between antidepressant use and pneumonia risk was confounded by comorbidity measures. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:911–8.

Sun Q, Zhang L, Wu Z, Hu D. Benzodiazepines or related drugs and risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:513–21.

Chung W-S, Lai C-Y, Lin C-L, Kao C-H. Adverse respiratory events associated with hypnotics use in patients of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based case–control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1110.

Wang M-T, Wang Y-H, Chang H-A, Tsai C-L, Yang Y-S, Lin CW, et al. Benzodiazepine and Z-drug use and risk of pneumonia in patients with chronic kidney disease: a population-based nested case–control study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179472.

Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, Stephenson AL, Gershon AS, Gruneir A, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:332–40.

Huybrechts KF, Rothman KJ, Silliman RA, Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S. Risk of death and hospital admission for major medical events after initiation of psychotropic medications in older adults admitted to nursing homes. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Medicale Can. 2011;183:E411–9.

Vozoris NT, Wang X, Austin PC, Stephenson AL, O’Donnell DE, Gershon AS, et al. Serotonergic antidepressant use and morbidity and mortality among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1800475.

Schindler JS, Kelly JH. Swallowing Disorders in the Elderly. The Laryngoscope. 2002;112:589–602.

Gambassi G, Sultana J, Trifirò G. Antipsychotic use in elderly patients and the risk of pneumonia. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14:1–6.

Nosè M, Recla E, Trifirò G, Barbui C. Antipsychotic drug exposure and risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:812–20.

Trifirò G. Antipsychotic drug use and community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011;13:262–8.

D’Souza R, Hooten WM. Extrapyramidal Symptoms (EPS). StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Florida: StatPearls Publishing; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534115/.

Miarons Font M, Rofes Salsench L. Antipsychotic medication and oropharyngeal dysphagia: systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2017;29. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/eurojgh/Fulltext/2017/12000/Antipsychotic_medication_and_oropharyngeal.3.aspx.

Trifirò G, Gambassi G, Sen EF, Caputi AP, Bagnardi V, Brea J, et al. Association of community-acquired pneumonia with antipsychotic drug use in elderly patients: a nested case–control study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(418–25):W139–40.

Pollmächer T, Haack M, Schuld A, Kraus T, Hinze-Selch D. Effects of antipsychotic drugs on cytokine networks. J Psychiatr Res. 2000;34:369–82.

Juergens SM. Problems with benzodiazepines in elderly patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:818–20.

Trifirò G, Spina E. Age-related changes in pharmacodynamics: focus on drugs acting on central nervous and cardiovascular systems. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:611–20.

Obiora E, Hubbard R, Sanders RD, Myles PR. The impact of benzodiazepines on occurrence of pneumonia and mortality from pneumonia: a nested case–control and survival analysis in a population-based cohort. Thorax. 2013;68:163–70.

Tune L. Anticholinergic effects of medication in elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;11–4.

Wichniak A, Wierzbicka A, Walęcka M, Jernajczyk W. Effects of antidepressants on sleep. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:63.

Cipriani A, La Ferla T, Furukawa T, Signoretti A, Nakagawa A, Churchill R, et al. Sertraline versus other antidepressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006117.pub2.

Magni L, Purgato M, Gastaldon C, Papola D, Furukawa T, Cipriani A, et al. Fluoxetine versus other types of pharmacotherapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004185.pub3.

Purgato M, Papola D, Gastaldon C, Trespidi C, Magni L, Rizzo C, et al. Paroxetine versus other anti-depressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006531.pub2.

Cipriani A, Purgato M, Furukawa T, Trespidi C, Imperadore G, Signoretti A, et al. Citalopram versus other anti-depressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006534.pub2.

Cipriani A, Koesters M, Furukawa T, Nosè M, Purgato M, Omori I, et al. Duloxetine versus other anti-depressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006533.pub2.

Carvalho AF, Sharma MS, Brunoni AR, Vieta E, Fava GA. The safety, tolerability and risks associated with the use of newer generation antidepressant drugs: a critical review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85:270–88.

Pellegrino TC, Bayer BM. Specific serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced decreases in lymphocyte activity require endogenous serotonin release. NeuroImmunoModulation. 2000;8:179–87.

Fazzino F, Montes C, Urbina M, Carreira I, Lima L. Serotonin transporter is differentially localized in subpopulations of lymphocytes of major depression patients. Effect of fluoxetine on proliferation. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;196:173–80.

Taler M, Gil-Ad I, Lomnitski L, Korov I, Baharav E, Bar M, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on human T lymphocyte function and gene expression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17:774–80.

Shenoy AR, Dehmel T, Stettner M, Kremer D, Kieseier BC, Hartung HP, et al. Citalopram suppresses thymocyte cytokine production. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;262:46–52.

Godhwani N, Bahna SL. Antiepilepsy drugs and the immune system. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:634–40.

Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, Gibbons MC, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112:228–42.

Shrank WH, Polinski JM, Avorn J. Quality indicators for medication use in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:S373–82.

Crotty M, Halbert J, Rowett D, Giles L, Birks R, Williams H, et al. An outreach geriatric medication advisory service in residential aged care: a randomised controlled trial of case conferencing. Age Ageing. 2004;33:612–7.

Yang S-Y, Liao Y-T, Liu H-C, Chen WJ, Chen C-C, Kuo C-J. Antipsychotic drugs, mood stabilizers, and risk of pneumonia in bipolar disorder: a nationwide case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:e79–86.

Shi T, Denouel A, Tietjen AK, Lee JW, Falsey AR, Demont C, et al. Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for pneumonia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz053.

Tong S, Amand C, Kieffer A, Kyaw MH. Trends in healthcare utilization and costs associated with pneumonia in the United States during 2008–2014. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:715.

Vila-Corcoles A, Ochoa-Gondar O, Rodriguez-Blanco T, Raga-Luria X, Gomez-Bertomeu F. Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia in older adults: a population-based study. Respir Med. 2009;103:309–16.

Singh RR, Nayak R. Impact of FDA black box warning on psychotropic drug use in noninstitutionalized elderly patients diagnosed with dementia: a retrospective study. J Pharm Pract. 2015;29:495–502.

Brown JD, Hutchison LC, Li C, Painter JT, Martin BC. Predictive Validity of the beers and screening tool of older persons’ potentially inappropriate prescriptions (STOPP) criteria to detect adverse drug events, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits in the united states. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:22–30.

Pazan F, Weiss C, Wehling M, FORTA. The EURO-FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) List: international consensus validation of a clinical tool for improved drug treatment in older people. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:61–71.

Albert SM, Colombi A, Hanlon J. Potentially inappropriate medications and risk of hospitalization in retirees: analysis of a US retiree health claims database. Drugs Aging. 2010;27:407–15.

Dedhiya SD, Hancock E, Craig BA, Doebbeling CC, Thomas J. Incident use and outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8:562–70.

Price SD, Holman CDJ, Sanfilippo FM, Emery JD. Association between potentially inappropriate medications from the beers criteria and the risk of unplanned hospitalization in elderly patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:6–16.

Fialová D, Topinková E, Gambassi G, Finne-Soveri H, Jónsson PV, Carpenter I, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use among elderly home care patients in Europe. JAMA. 2005;293:1348–58.

Pasina L, Djade CD, Tettamanti M, Franchi C, Salerno F, Corrao S, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications and risk of adverse clinical outcome in a cohort of hospitalized elderly patients: results from the REPOSI Study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39:511–5.

Renom-Guiteras A, Meyer G, Thürmann PA. The EU(7)-PIM list: a list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people consented by experts from seven European countries. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:861–75.

Finnish Medicines Agency. Meds75 + [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Sep 11]. Available from: https://www.fimea.fi/web/en/databases_and_registeries/medicines_information/database_of_medication_for_the_elderly.

Rognstad S, Brekke M, Fetveit A, Spigset O, Wyller TB, Straand J. The Norwegian General Practice (NORGEP) criteria for assessing potentially inappropriate prescriptions to elderly patients. A modified Delphi study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27:153–9.

Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, Fakhran S, Balk R, Bramley AM, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415–27.

GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1545–602.

Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jönsson B, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:655–79.

World Health Organization. Mental health of older adults [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults.

Harris T, Carey IM, Shah SM, DeWilde S, Cook DG. Antidepressant prescribing in older primary care patients in community and care home settings in England and Wales. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:41–7.

Azermai M, Petrovic M, Elseviers MM, Bourgeois J, Van Bortel LM, Vander Stichele RH. Systematic appraisal of dementia guidelines for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms. Ageing Res Rev. 2012;11:78–86.

Zuidema SU, Johansson A, Selbaek G, Murray M, Burns A, Ballard C, et al. A consensus guideline for antipsychotic drug use for dementia in care homes. Bridging the gap between scientific evidence and clinical practice. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:1849–59.

Jackson JW, VanderWeele TJ, Blacker D, Schneeweiss S. Mediators of first- versus second-generation antipsychotic-related mortality in older adults. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 2015;26:700–9.

Aparasu RR, Chatterjee S, Chen H. Risk of pneumonia in elderly nursing home residents using typical versus atypical antipsychotics. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:464–74.

Huybrechts KF, Schneeweiss S, Gerhard T, Olfson M, Avorn J, Levin R, et al. Comparative safety of antipsychotic medications in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:420–9.

Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Setoguchi S, Patrick A, Avorn J, Mogun H, et al. Ventricular arrhythmias and cerebrovascular events in the elderly using conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:707–10.

Mehta S, Pulungan Z, Jones BT, Teigland C. Comparative safety of atypical antipsychotics and the risk of pneumonia in the elderly. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:1271–80.

Gau J-T, Acharya U, Khan S, Heh V, Mody L, Kao T-C. Pharmacotherapy and the risk for community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:45.

Knol W, van Marum RJ, Jansen PAF, Souverein PC, Schobben AFAM, Egberts ACG. Antipsychotic drug use and risk of pneumonia in elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:661–6.