Abstract

Background and Objectives

Acute postoperative pain management in the geriatric patient can be challenging, including their response to medications. The purpose of this analysis was to evaluate whether the efficacy and safety profile of fentanyl iontophoretic transdermal system (ITS) (IONSYS®) was similar in geriatric (≥65 years) and non-geriatric (<65 years) patients.

Methods

Efficacy and safety data from three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials and four randomized, open-label, active-comparator trials were utilized for this analysis. Efficacy was assessed via the patient global assessment (PGA) and the investigator global assessment (IGA) scales. The PGA and IGA are categorical 4-point scales (excellent, good, fair, or poor) with treatment success defined as excellent or good. Safety was evaluated via adverse events.

Results

A total of 1763 patients were assigned to the fentanyl ITS treatment group. Of the 1763 patients in the fentanyl ITS group, 499 patients were ≥65 years of age; 65.1% were 65–74 years of age, 31.7% were 75–84 years of age, and 3.2% were ≥85 years of age. In the fentanyl ITS treatment groups, there were no statistically significant differences between the non-geriatric and geriatric patients in terms of patients reporting success on the PGA at 24 h (80.0 vs. 83.0%, respectively; p = 0.3415). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in success rates on the IGA at study discharge (82.8 vs. 87.5%, respectively; p = 0.1195). The safety profile was similar between the age groups.

Conclusions

Overall, efficacy and safety of the fentanyl ITS were similar between the geriatric and non-geriatric patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Fentanyl iontophoretic transdermal system (ITS) has been studied in phase III and IIIb studies in more than 1700 patients. |

Fentanyl ITS was similarly effective and had a similar safety profile for geriatric and non-geriatric patients for the management of postoperative pain. |

Fentanyl ITS may be a valuable additional option for the treatment of postoperative pain in geriatric patients. |

1 Background

The population is aging in nearly all countries of the world [1]. Globally, the number of people who are 60 years or older is expected to double from 841 million people in 2013 to more than 2 billion in 2050 [1]. In the USA, the population over 65 years of age is expected to grow from 15 to 24% of the total population, which translates into 98 million people over 65 years of age by 2060 [2]. In fact, the older population is aging as well. The share of people over the age of 80 years is expected to reach 19% of the population by 2050 [1]. Geriatric patients have higher rates per population of surgical procedures than other age groups [3–5]. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the effectiveness and risks of medications used in the perioperative period.

Effective postoperative pain management is as important in the geriatric surgical patient as it is in the younger patient as it can reduce morbidity and lead to earlier ambulation [6]. In fact, clinical evidence shows that aggressive pain management in geriatric patients can improve outcomes [7]. Poorly controlled pain is one of the risk factors for delirium in the geriatric patient [7]. It is also important to note that opioids can be a risk for delirium in geriatric patients.

Fentanyl iontophoretic transdermal system (ITS) (IONSYS®, The Medicines Company, Parsippany, NJ, USA) is a non-invasive patient-controlled approach to postoperative pain management. The fentanyl ITS is a prefilled, pre-programmed system that delivers fentanyl transdermally via iontophoresis using a virtually imperceptible low-intensity electric field [8]. The patient activates a dose by double-pressing a recessed button, and the system then delivers a nominal 40 µg dose of fentanyl over a period of 10 min. Fentanyl ITS eliminates the potential for programming errors [9]. Patient mobility is unhindered by the system, as no cable, tubing, or external pump interferes with patients’ activities. Additionally, staff time spent on more invasive routes of administration may be reduced [10, 11].

Fentanyl ITS has been well-studied in three phase III and four phase IIIb clinical studies (Table 1) [12–18]. In the three placebo-controlled phase III studies, fentanyl ITS was superior to placebo in terms of acute postoperative pain management as assessed by the number or percentage of patients withdrawn due to inadequate pain control after completing at least 3 h of study treatment [12–14]. In the four active-comparator phase IIIb studies, fentanyl ITS demonstrated similar efficacy to morphine intravenous (IV) patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) on the primary outcome measure (i.e., 24-h treatment success rate, determined as a rating of ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ on the validated patient-reported outcome measure of the patient global assessment [PGA] of the method of pain control) [15–19].

Geriatric patients have changes in physiology and do not always respond to medications in the same fashion as their younger counterparts [20]. Therefore, it is important to understand for any medication whether there are differences in efficacy in a geriatric population compared with a non-geriatric population. This is especially true as the populations continues to age. For opioids, it is particularly important to understand safety, especially around respiratory depression in a population more at risk for it such as with geriatric patients. Therefore, in this report we compared the efficacy and safety of patients less than 65 years of age with those greater than 65 years of age to determine whether there are any meaningful differences of clinical relevance for the clinician.

2 Methods

PubMed and the Cochrane Library were searched combining the terms “fentanyl” and “iontophoretic” for the period of 1980 to 30 June 2016 (Fig. 1). A search of the ClinicalTrials.gov database was also conducted for the same period using the terms “fentanyl” and “iontophoretic”. Studies were included if they evaluated the fentanyl ITS in prospective, randomized controlled trials. This literature search resulted in six unique clinical trials that are included in this meta-analysis [13–18]. The manufacturer provided details on a seventh phase III trial that has not been published [12]. The details of each trial are presented in Table 1. A risk of bias assessment was completed (Fig. 2). All studies received applicable Institutional Review Board approval prior to initiation and all patients who participated in the study provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment. Non-opioid analgesics were permitted in one of the clinical trials at the discretion of local practice and were not standardized [18]. The efficacy endpoint for the purpose of these analyses was the 24-h treatment success rate, determined as a rating of ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ on the validated measure of the PGA of the method of pain control (assessed as the last PGA recorded in the first 24 h) [19]. A key secondary efficacy endpoint included the investigator global assessment (IGA) completed at 24 h. Safety was assessed via treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs). For the purpose of these analyses, the following subgroups were utilized: geriatric age groups (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years) and the non-geriatric age group (<65 years). Six of the studies have been previously published with full methodology [13–18]. The seventh study was a placebo-controlled trial similar in design to the other two placebo-controlled trials. The purpose of this analysis was to evaluate whether the efficacy and safety profile of fentanyl ITS was similar between geriatric (≥65 years) and non-geriatric (<65 years) patients.

2.1 Statistical Analysis

To be considered evaluable for the efficacy population analysis, patients had to have at least 3 h of study treatment (evaluable for efficacy population). The safety population included all patients who received any study treatment (safety population).

The treatment success rate, determined as a rating of ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ on the validated PGA of the method of pain control was the primary efficacy endpoint in the four phase IIIb trials and was collected in all of the phase III trials. Therefore, this was chosen to be the primary outcome for this meta-analysis. For all of the efficacy outcomes, a meta-analysis using random effect models according to Cochrane methodology to generate p-values was employed. For dichotomous variables, odds ratios (ORs) indicating the probability of the outcome to occur were calculated. Statistical tests were performed at the 0.05 significance level, with no multiplicity adjustments. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) were provided. Descriptive statistics were utilized for the safety outcomes.

3 Results

In the fentanyl ITS controlled studies, a total of 1763 patients were in the fentanyl ITS group, 1313 were in the morphine IV PCA group, and 316 were in the placebo group. Of the 1763 patients in the fentanyl ITS group, 499 patients were ≥65 years of age; 65.1% (n = 325) were 65–74 years of age, 31.7% (n = 158) were 75–84 years of age, and 3.2% (n = 16) were ≥85 years of age (Table 1). Of the 1313 patients in the morphine IV PCA group, 382 were ≥65 years of age; 61.3% (n = 234) were 65–74 years of age, 35.3% (n = 135) were 75–84 years of age, and 3.4% (n = 13) were ≥85 years of age (Table 1). Of the patients in the placebo group, 66 patients were ≥65 years of age; 66.7% (n = 44) were 65–74 years of age, 30.3% (n = 20) were 75–84 years of age, and 3.0% (n = 2) were ≥85 years of age (Table 1).

In the fentanyl ITS controlled studies, demographic and baseline characteristics across geriatric and non-geriatric patients in fentanyl ITS patients are presented below in Table 2. A higher percentage of geriatric patients were Caucasian. A larger proportion of geriatric patients had undergone orthopedic bone procedures compared with the non-geriatric patients and a smaller proportion of geriatric patients had undergone lower abdominal procedures compared with the non-geriatric patients.

3.1 Efficacy

3.1.1 Doses Used

Non-geriatric patients used a mean of 32.4 doses of fentanyl ITS in the first 24 h, while geriatric patients used a mean of 24.0 doses of fentanyl ITS in that same period. For the patients who remained on treatment, the mean number of doses of fentanyl ITS was 24.2 and 17.4 for 24–48 and 48–72 h, respectively, in non-geriatric patients, whereas the mean number of doses was 17.1 and 16.0 for 24–48 and 48–72 h, respectively, in the geriatric patients. A similar trend was seen with morphine IV PCA dosing between the geriatric and non-geriatric patients.

3.1.2 Patient Global Assessment and Investigator Global Assessment of Method of Pain Control

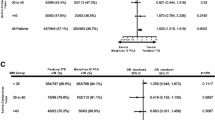

The success on the PGA for non-geriatric and geriatric patients at 24 h (989/1236 [80.0%] and 406/489 [83.0%], respectively; adjusted OR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.61–1.19, p = 0.3415) indicates that geriatric patients have slightly higher (17.6%) odds (1/0.85) of achieving success than non-geriatric patients but there are no statistically significant differences between these two groups of patients (Fig. 3). The percentage of patients reporting success on the PGA was similar across all age groups in the fentanyl ITS treatment groups (<65 years: 80.0%; 65–74 years: 83.4%; 75–84 years: 81.8%; and ≥85 years: 86.7%).

Patient global assessment of the method of pain control at 24 h in patients treated with fentanyl iontophoretic transdermal system. There were no statistically significant differences between the non-geriatric and geriatric patients in terms of patients reporting success in the total patient population on the patient global assessment at 24 h (80.0 vs. 83.0%, respectively; p = 0.3415). For study 095-16, 100% of patients achieved success in the >65 years group. This resulted in infinity odds of success in the >65 years group, hence the odds ratio and its 95% confidence interval cannot be calculated. In this situation, the p value that tests null hypothesis “the same success rate in ≤65 years and >65 years group” is an appropriate statistic to look at. CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio

Similarly, there were no statistically significant differences between non-geriatric (<65 years) and geriatric (≥65 years) patients in terms of patients reporting success on the IGA at study discharge (1024/1236 [82.8%] vs. 428/489 [87.5%], respectively; OR = 0.851, 95% CI 0.610–1.187; p = 0.1195). The percentage of patients reporting success on the IGA was similar across all age groups (<65 years: 82.8%; 65–74 years: 86.9%; 75–84 years: 89.0%; and ≥85 years: 86.7%).

In both the placebo-controlled and the active-comparator trials, the proportion of patients in the fentanyl ITS group who rated their method of pain control as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ was similar in each of the geriatric age groups (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years) to that in the non-geriatric age group (<65 years) (Table 3). Likewise, the proportion of investigators who rated the method of pain control as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ in the fentanyl ITS group was similar in each of the geriatric age groups (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years) to that in the non-geriatric age group (<65 years) (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences caused by fentanyl in proportion in either the PGA or IGA between geriatric patients and non-geriatric patients (Table 4).

3.2 Safety

3.2.1 Early Discontinuation due to an Adverse Event (AE)

The proportion of patients in the fentanyl ITS group who discontinued due to an adverse event (AE) was similar among the geriatric subgroups (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years of age) and the non-geriatric group (<65 years of age) (Table 5). The rate of discontinuation due to an AE in the fentanyl ITS group was not correlated with age. Less than 5% of patients in the controlled studies discontinued treatment with fentanyl ITS because of an AE (77/1763 [4.4%] overall). A similar proportion of patients discontinued for AEs in the IV PCA morphine (87/1313 [6.6%]) and placebo treatment groups (8/316 [2.5%]).

3.2.2 AEs in Placebo-Controlled Studies

In the placebo-controlled studies the incidence of AEs such as pyrexia, headache, and insomnia, likely reflecting postoperative effects, were similar between the two treatment groups. Typical opioid AEs such as nausea, dizziness, pruritus, and urinary retention were experienced more often with fentanyl ITS than with placebo. A higher incidence of application-site erythema, vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention, and back pain occurred in the non-geriatric patients, and a higher incidence of anemia and hypotension occurred in the geriatric patients (Tables 6, 7).

3.2.3 AEs in the Active-Comparator Studies

In the active-comparator studies with IV PCA morphine, most of the AEs reported in ≥2% of patients were comparable between the two treatment groups (Tables 6, 7). AEs that occurred at a higher incidence in the non-geriatric patients were nausea, application-site erythema, headache, dizziness, application-site vesicles, and abdominal pain.

3.2.4 Respiratory and Central Nervous System Effects

In the controlled studies, AEs suggestive of central nervous system (CNS) or respiratory depression occurred infrequently overall, but were more common in patients receiving morphine IV PCA (8.6%) than in those receiving fentanyl ITS (5.0%). Compared with patients receiving fentanyl ITS, a greater proportion of patients receiving IV PCA morphine experienced the AEs of hypoxia, hypoventilation, somnolence, and confusional state. Apnea occurred at a similar frequency in both active treatment groups. The incidence of all selected AEs and bradypnea was lower in the placebo-treated patients.

In the controlled studies in fentanyl ITS patients, the rate of AEs suggestive of CNS or respiratory depression appeared to increase with age: at least one AE suggestive of CNS or respiratory depression was reported in 3.7% of non-geriatric patients, 7.1% of patients 65–74 years, 10.1% of patients 75–84 years, and 18.8% of patients ≥85 years of age. The incidence of each individual AE was low, and there were no particular AEs markedly elevated in the geriatric patients.

3.2.5 AEs Resulting in Study Termination

In the controlled studies, the incidence of AEs resulting in study termination in fentanyl ITS patients, morphine IV PCA patients, and placebo patients was similar across the age groups (Table 8).

4 Discussion

In the fentanyl ITS clinical development program, there were 499 patients ≥65 years of age treated with fentanyl ITS. The entire ≥65 years population were used to assess the safety (safety population) and 489 were used to assess efficacy (evaluable for efficacy population) of fentanyl for postoperative pain management in geriatric patients. Overall, there were no meaningful differences in efficacy assessment outcomes in each of the geriatric subgroups (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years) compared with the non-geriatric group (<65 years) in the placebo- and active-controlled studies. The proportion of patients in the fentanyl ITS group who rated their method of pain control as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ was similar in each of the geriatric patients to that in the non-geriatric patients. Similarly, the proportion of investigators who rated the method of pain control as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ in the fentanyl ITS group was similar in each of the geriatric subgroups to that in the non-geriatric group. Therefore, it would appear as though fentanyl ITS is equally effective in geriatric patients as it is in non-geriatric patients.

Overall, the safety profile that was observed was similar between the geriatric and non-geriatric patients. The rate of discontinuation due to an AE in the fentanyl ITS group was not correlated with age. There was not a clinically meaningful difference between the non-geriatric and geriatric patients in terms of TEAEs. Not surprisingly, in the placebo-controlled trials the typical opioid AEs such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, pruritus, and urinary retention were experienced more often with fentanyl ITS than with placebo. Only anemia and hypotension occurred at a higher incidence in the geriatric patients than the non-geriatric patients. However, it is doubtful that anemia is a true drug effect as blood loss is common in this postoperative group and fluid shifts are common. While hypotension occurred more frequently in the 65–74 years age group than it did in the <65 years group, there were no reports in either the 75–84 or ≥85 years groups. In the active-comparator studies with IV PCA morphine, most of the AEs reported were comparable between the two treatment groups. In these studies, only anemia occurred at a higher incidence in the geriatric patients than in the non-geriatric patients.

In the active-comparator studies, AEs suggestive of CNS or respiratory depression occurred infrequently. Overall, the rate of AEs suggestive of CNS or respiratory depression appeared to increase with age, as would be expected for this population. However, it is important to note that the AEs suggestive of CNS or respiratory depression, while infrequent, were more common in patients receiving morphine IV PCA (8.6%) than in those receiving fentanyl ITS (5.0%). As with all patients, it is prudent to monitor geriatric patients closely for signs of sedation and respiratory depression, especially when either initiating treatment with fentanyl ITS or when fentanyl ITS is given concomitantly with other drugs that are known to be respiratory depressants.

Postoperative mobility is important for any patient undergoing surgery, but especially so in a geriatric patient who may already be more predisposed to some of the complications of immobility such as deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections [21]. Mobility can be hindered by IV lines and poles. Fentanyl ITS has an advantage over morphine IV PCA in that it does not require an IV line and pump. It is important to note that patients may still require IV fluid support in the postoperative period and may require an IV line for that purpose. In addition, venous access can sometimes be challenging in geriatric patients due to the overall structure of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and veins, with veins that can become fragile, twisted, or hardened [22, 23] and therefore fentanyl ITS can be an advantage in this situation.

There is some conflicting literature that suggests that the clearance of fentanyl may be reduced and the terminal half-life prolonged in the geriatric patient [24, 25]. However, in a pharmacokinetic study of fentanyl ITS conducted in 63 healthy volunteers (25 subjects older than 65 years), age did not seem to affect the extent of drug absorption significantly and the pharmacokinetics were unaffected [26].

The population is aging and geriatric patients are vulnerable and particularly sensitive to the stresses associated with surgeries [27]. Adequate pain control is as important in this population as it is in the non-geriatric population. However, there are times when geriatric patients respond differently to medications. This analysis suggests that fentanyl ITS is as effective and similarly tolerated in the geriatric and non-geriatric patients.

One of the limitations for using fentanyl ITS, IV PCA, or any PCA is that patients need to be alert enough and have adequate ability to understand the directions for use. Each patient needs to be carefully assessed, both geriatric and non-geriatric, in order to ensure that they have the cognitive function to utilize these systems effectively and to reinforce the instructions for use of each system as necessary. A limitation of this meta-analysis was that the population was not evenly distributed. In this case there were many more non-geriatric patients than geriatric patients. Also, there were very few patients who were ≥85 years of age. Another limitation of this meta-analysis is that none of the studies were designed to look specifically at the geriatric population, although the geriatric subgroup in this study is not small and the overall subgroup findings are consistent with the overall study results.

Further studies specifically looking at geriatric patients should be conducted to confirm the results of the meta-analysis. Longer-term outcomes (i.e., post-discharge) and cognitive status are two additional outcomes that should be considered for future studies.

5 Conclusions

The results of this analysis suggest that there were no meaningful differences in terms of efficacy in each of the geriatric age groups compared with the non-geriatric group. Additionally, the safety profile of fentanyl ITS was fairly similar in the geriatric patients to that of the non-geriatric patients. These results suggest that fentanyl ITS may be a valuable additional option for the treatment of postoperative pain in geriatric patients.

References

United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World population ageing 2013. 2013. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2013.pdf. Accessed 21 Apr 2015.

Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. Population estimates and projections. 2015. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Accessed 21 Apr 2015.

DeFrances CJ, Lucas CA, Buie VC, Golosinskiy A. 2006 national hospital discharge survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;30(5):1–20.

Hall MJ, DeFrances CJ, Williams SN, Golosinskiy A, Schwartzman A. National hospital discharge survey: 2007 summary. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2010;26(29):1–20, 24.

Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2009;28(11):1–25.

Dubljanin-Raspopovic E, Markovic-Denic L, Ivkovic K, Nedeljkovic U, Tomanovic S, Kadija M, et al. The impact of postoperative pain on early ambulation after hip fracture. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2013;60(1):61–4.

Colon-Emeric CS. Postoperative management of hip fractures: interventions associated with improved outcomes. Bonekey Rep. 2012;1:241.

Batheja P, Thakur R, Michniak B. Transdermal iontophoresis. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2006;3(1):127–38.

Viscusi ER, Schechter LN. Patient-controlled analgesia: Finding a balance between cost and comfort. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(8 Suppl 1):S3–13 (quiz S5–6.

Bonnet F, Eberhart L, Wennberg E, Dodds SJ, Van Bellinghen L, Annemans L, et al. Fentanyl HCl iontophoretic transdermal system versus morphine IV-PCA for postoperative pain management: survey of healthcare provider opinion. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(2):293–301.

Evans C, Schein J, Nelson W, Crespi S, Gargiulo K, Horowicz-Mehler N, et al. Improving patient and nurse outcomes: a comparison of nurse tasks and time associated with two patient-controlled analgesia modalities using delphi panels. Pain Manag Nurs. 2007;8(2):86–95.

Data on file, The Medicines Company, 2016.

Chelly JE, Grass J, Houseman TW, Minkowitz H, Pue A. The safety and efficacy of a fentanyl patient-controlled transdermal system for acute postoperative analgesia: a multicenter, placebo-controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(2):427–33.

Viscusi ER, Reynolds L, Tait S, Melson T, Atkinson LE. An iontophoretic fentanyl patient-activated analgesic delivery system for postoperative pain: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(1):188–94.

Viscusi ER, Reynolds L, Chung F, Atkinson LE, Khanna S. Patient-controlled transdermal fentanyl hydrochloride vs intravenous morphine pump for postoperative pain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1333–41.

Hartrick CT, Bourne MH, Gargiulo K, Damaraju CV, Vallow S, Hewitt DJ. Fentanyl iontophoretic transdermal system for acute-pain management after orthopedic surgery: a comparative study with morphine intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006;31(6):546–54.

Minkowitz HS, Rathmell JP, Vallow S, Gargiulo K, Damaraju CV, Hewitt DJ. Efficacy and safety of the fentanyl iontophoretic transdermal system (ITS) and intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV PCA) with morphine for pain management following abdominal or pelvic surgery. Pain Med. 2007;8(8):657–68.

Grond S, Hall J, Spacek A, Hoppenbrouwers M, Richarz U, Bonnet F. Iontophoretic transdermal system using fentanyl compared with patient-controlled intravenous analgesia using morphine for postoperative pain management. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98(6):806–15.

Rothman M, Vallow S, Damaraju CV, Hewitt DJ. Using the patient global assessment of the method of pain control to assess new analgesic modalities in clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(6):1433–43.

McKeown JL. Pain management issues for the geriatric surgical patient. Anesthesiol Clin. 2015;33(3):563–76.

Sanguineti VA, Wild JR, Fain MJ. Management of postoperative complications: general approach. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(2):261–70.

Kimori K, Sugama J. Investigation of vasculature characteristics to improve venepuncture techniques in hospitalized elderly patients. Int J Nurs Pract. 2016;22(3):300-6. doi:10.1111/ijn.12430.

Hoggard J, Saad T, Schon D, Vesely TM, Royer T, American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology, Clinical Practice Committee; Association for Vascular Access. Guidelines for venous access in patients with chronic kidney disease. A Position Statement from the American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology, Clinical Practice Committee and the Association for Vascular Access. Semin Dial. 2008;21(2):186–91.

Mather LE. Clinical pharmacokinetics of fentanyl and its newer derivatives. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1983;8(5):422–46.

Scholz J, Steinfath M, Schulz M. Clinical pharmacokinetics of alfentanil, fentanyl and sufentanil: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;31(4):275–92.

Gupta SK, Hwang S, Southam M, Sathyan G. Effects of application site and subject demographics on the pharmacokinetics of fentanyl HCl patient-controlled transdermal system (PCTS). Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(Suppl 1):25–32.

Aubrun F, Gazon M, Schoeffler M, Benyoub K. Evaluation of perioperative risk in elderly patients. Minerva Anestesiol. 2012;78(5):605–18.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge writing assistance provided by Starr Grundy of SD Scientific, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflicts of interest

Eugene R. Viscusi is Professor of Anesthesiology and Director, Acute Pain Management at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA. He declares the following potential conflicts of interest: funded research to his institution—AcelRx and Pacira; consulting—AcelRx, The Medicines Company, Mallinckrodt, Cubist, Trevena, and Pacira; speaking honoraria—AstraZeneca, Mallinckrodt, Cubist, Salix, and Pacira. Li Ding and Loretta M. Itri are employees of The Medicines Company (Parsippany, NJ, USA).

Funding

The analyses and writing of this manuscript were supported financially by The Medicines Company.

Ethical approval and informed consent

All studies received applicable Institutional Review Board approval prior to initiation. All patients who participated in the study provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment.

Authors’ contributions

ERV was involved in the interpretation of the data, critically reviewing and revising the manuscript, gave final approval of the current submitted version of the paper, and agrees in conjunction with his co-authors to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work. LD was involved in the conception of the analysis plan, conducting the analysis, and quality control of the analysis. She was also involved in critically reviewing and revising the manuscript, gave final approval of the current submitted version of the paper, and agrees in conjunction with her co-authors to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work. LI was involved in the conception of the analysis plan. She was also involved in critically reviewing and revising the manuscript, gave final approval of the current submitted version of the paper, and agrees in conjunction with her co-authors to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Viscusi, E.R., Ding, L. & Itri, L.M. The Efficacy and Safety of the Fentanyl Iontophoretic Transdermal System (IONSYS®) in the Geriatric Population: Results of a Meta-Analysis of Phase III and IIIb Trials. Drugs Aging 33, 901–912 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-016-0409-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-016-0409-7