Abstract

Introduction

The glomerular filtration rate (GFR), a measure of renal function, decreases by approximately 10 mL/min every 10 years after the age of 40 years, which could lead to the accumulation of drugs and/or renal toxicity. Pharmacokinetic studies of drugs excreted both renally and non-renally are desirable in patients with impaired renal function, defined by parameters including estimated GFR (eGFR) and creatinine clearance (CLCR).

Objective

We describe here a population pharmacokinetic analysis of the possible effects of renal impairment on steady-state plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and its metabolite NAP226-90 after rivastigmine patch (5 cm2 [4.6 mg/24 h], 10 cm2 [9.5 mg/24 h], 15 cm2 [13.3 mg/24 h], and 20 cm2 [17.4 mg/24 h]) and capsule (1.5, 3, 4.5, and 6 mg/12 h) treatment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Methods

The data used to conduct the current pharmacokinetic analysis were obtained from the pivotal phase III, 24-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel-group study (IDEAL). One blood sample was collected from each patient at steady-state to measure plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 using a liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) method. The steady-state plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 were plotted against CLCR and eGFR data, and boxplots were constructed after stratification by renal function.

Results

The two groups (mild/no renal impairment vs. moderate/severe/end-stage renal impairment) showed comparable demographic covariates for all patch sizes and capsule doses. No correlation was observed between CLCR or eGFR and plasma concentrations of rivastigmine or NAP226-90. Boxplots of concentrations of rivastigmine or NAP226-90 for each dose largely overlapped for patch and capsule. Additionally, model-based estimates of plasma concentrations adjusted for body weight yielded similar results.

Conclusion

The results of this study show that renal function does not affect rivastigmine or NAP226-90 steady-state plasma concentrations, and no dose adjustment in patients with renal impairment is required.

ClinicalTrials.gov

NCT00099242.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

We performed a large population pharmacokinetic modeling analysis of the possible effects of renal impairment on steady-state plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and its metabolite, after rivastigmine patch and capsule treatment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. |

No correlation was observed between creatinine clearance or estimated glomerular filtration rate and plasma concentrations of rivastigmine or its metabolite, indicating that renal function did not impact steady-state plasma concentrations of rivastigmine or its metabolite. |

Consequently, no dose adjustment in patients with renal impairment is required. This is a key finding allowing all Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease dementia patients to benefit from most optimal therapeutic doses of rivastigmine, irrespective of their renal function status. |

1 Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) primarily affect older individuals aged >65 years and their prevalence increases with age [1, 2]. The risk of renal impairment is higher in elderly people, as shown in several longitudinal and cross-sectional studies supporting a decline in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) with advancing age [3–5]. Renal impairment may result in increased plasma concentrations of drugs and their metabolites, potentially resulting in toxicity. It is important to assess the renal function of patients before prescribing drugs that are excreted renally or are known to cause renal impairment or nephrotoxicity.

Rivastigmine is a slowly reversible (pseudo-irreversible), centrally selective dual inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase, which increases the available acetylcholine levels and improves neurotransmission in AD. It has established efficacy in the symptomatic treatment of AD [6–8] and PDD [9] and has been shown to improve activities of daily living, cognition, behavior, and global function [7, 10–12]. Another study reported similar benefits of rivastigmine in more advanced stages of the disease [13]. Studies of dose–response relationships for cholinesterase inhibitors support greater enzyme inhibition, in turn leading to higher efficacy and long-term benefits with higher drug doses [14].

Rivastigmine has been developed for oral twice-daily administration as a capsule (3, 6, 9, and 12 mg/day) and solution (2 mg/mL), and for transdermal daily administration as a patch (5 cm2 [4.6 mg/24 h], 10 cm2 [9.5 mg/24 h], 15 cm2 [13.3 mg/24 h], and 20 cm2 [17.4 mg/24 h]) (of note, the 20 cm2 patch has not been launched into the market to date).

Rivastigmine is rapidly and extensively metabolized by its target esterase enzymes, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase, to NAP266-90, an inactive and non-toxic major metabolite of rivastigmine [15], which is then excreted renally via sulfate conjugation. Although rivastigmine is not (or in trace amounts) excreted unchanged in urine (2–4 % of the dose) [16, 17], investigating the effects of renal function on drug exposure is critical to ensure safe administration of the effective dose of rivastigmine in patients. Accordingly, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) draft guidance (2010), Pharmacokinetics in Patients with Impaired Renal Function—Study Design, Data Analysis, and Impact on Dosing and Labeling, recommends pharmacokinetic studies in patients with impaired renal function for drugs that are excreted both renally and non-renally, and staging of kidney function using estimated GFR (eGFR) and creatinine clearance (CLCR) values [18]. As described in the FDA draft guidance [19], a population pharmacokinetic approach in a phase III study with rivastigmine patch and capsule in AD patients with renal impairment was used in place of a specific reduced pharmacokinetic study [18]. Although NAP226-90 is inactive and non-toxic, it was also desirable to investigate the effects of renal function on the steady-state plasma concentrations of NAP226-90, which is an indicator of the extent of rivastigmine metabolism [20] and is excreted renally, amounting to approximately 20 % of the equivalent rivastigmine dose [16].

The current pharmacokinetic analysis aimed to evaluate the possible effects of renal function on drug exposure. The aim of the analysis was to compare (1) the observed rivastigmine and NAP226-90 steady-state plasma concentrations in patients with either mild or no renal impairment at baseline with the corresponding concentrations in patients with moderate or severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease (ESRD); and (2) the observed steady-state plasma concentrations versus CLCR and eGFR of rivastigmine and NAP226-90.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

The data used to conduct the pharmacokinetic analysis described in this report were obtained from the pivotal phase III, 24-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel-group study (IDEAL [Investigation of transDermal Exelon in ALzheimer’s disease]; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00099242) [21]. The study population included 1195 elderly adults with probable AD recruited at 100 different sites in 21 countries. The protocol, informed consent form, any amendments, and other information given to patients and caregivers were reviewed by an Institutional Review Board or Independent Ethics Committee for each center. A total of 101 Independent Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards across the world were responsible to approve these documents and forms (see Winblad et al. [21, 22] for further details). The study was conducted according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2000.

The efficacy, safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of rivastigmine (Exelon®) once-daily patch (5, 10, 15, and 20 cm2) and twice-daily capsule (3, 6, 9, and 12 mg/day) formulations were evaluated in patients aged between 50 and 85 years with probable AD (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score: 10–20) from 2003 to 2006 [21, 22]. The capsule formulation was the active control arm. This study provided rivastigmine and NAP226-90 (metabolite) concentration data on the four patch sizes (5 cm2 [4.6 mg/24 h), 10 cm2 [9.5 mg/24 h], 15 cm2 [13.3 mg/24 h], and 20 cm2 [17.4 mg/24 h]), and on the four capsule doses (3, 6, 9, and 12 mg/day). One blood sample (3 mL) was collected from each patient to measure steady-state concentrations of rivastigmine and its metabolite NAP226-90 in plasma. All patients were sampled towards the end of the study period while on their maintenance dose, i.e., after 8 weeks of treatment with the same stable daily dose, ensuring complete steady-state conditions (reached after a few days for both rivastigmine and NAP226-90). Only those measurements confirmed to be obtained at steady state were included in the pharmacokinetic evaluation.

2.2 Pharmacokinetic Analysis

Rivastigmine and its metabolite NAP226-90 were determined in plasma by using liquid/liquid extraction followed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization mode, with a limit of quantitation (LOQ) of 0.2 ng/mL for both compounds, using 500 μL of human plasma [23]. The validation of the method is described elsewhere [23]. The study between-run variability was tested using quality control samples with low (0.4 ng/mL), medium (7.5 ng/mL), and high (25 ng/mL) concentrations, and ranged from 1.9 to 3.9 % for rivastigmine and 6.3 to 8.3 % for NAP226-90.

According to the FDA draft guidance (2010), renal function at baseline was quantified by CLCR in addition to eGFR [18]. CLCR and eGFR were estimated (not measured) as follows.

CLCR was estimated by the Cockcroft-Gault method (CLCR-CG) [24]. The equation for men (Eq. 1) is as follows:

The CLCR equation for women (Eq. 2) is as follows:

eGFR was estimated based on the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula (eGFR-MDRD) [25, 26] as follows (Eq. 3):

Using the estimated values for CLCR (mL/min) and eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) at baseline, patients were assigned to the following five renal impairment groups: control/normal renal function, ≥90; mild renal impairment, 60 to <90; moderate renal impairment, 30 to <60; severe renal impairment, 15 to <30; and ESRD <15. Due to the small proportion of patients in certain categories, the patients were pooled into two broader groups to facilitate comparison of drug exposure between the groups: (1) controls and mild renal impairment; and (2) moderate and severe renal impairment and ESRD. The group with mild or no renal impairment served as the ‘control group’ for comparison with the ‘renal impairment group’ comprising patients with moderate and severe renal impairment and ESRD. From here on, these two groups are referred to as the control group and the renal impairment group, respectively.

Boxplots were constructed for the observed steady-state plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 stratified by baseline renal function. The observed steady-state plasma concentrations were plotted against CLCR and eGFR.

A covariate search on the same study data [21] to determine the relationship of patient demographics with steady-state plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 showed a significant relationship between drug exposure and body weight, which was expressed by Eqs. 4 and 5. The steady-state plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 in patients with various body weights relative to the steady-state plasma concentrations in a patient weighing 65 kg were estimated as follows:

and

where SS indicates steady state.

Using this known relationship between body weight and plasma rivastigmine or NAP226-90 concentrations, the analyses described above were repeated with the model-based estimates of plasma concentrations adjusted to a body weight of 65 kg.

3 Results

When stratified by renal impairment using CLCR and eGFR, the two treatment patient groups showed comparable values for demographic covariates such as age, weight, and MMSE score at baseline across all patch sizes (Table 1) and capsule doses (Table 2). There were no ESRD patients.

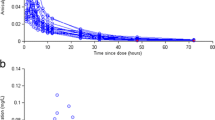

The boxplots depicting the steady-state plasma concentrations stratified by renal impairment (CLCR or eGFR) for both rivastigmine and NAP226-90 largely overlapped for both patient groups within each dose level of patch (Fig. 1) and capsule (Fig. 2) applications. The arithmetic means with standard deviation, and the geometric means with 95 % confidence intervals (and geometric mean ratios) of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 concentrations for each patient group at each dose level are shown in Table 3 (stratified by CLCR and eGFR) for rivastigmine, Table 4 (stratified by CLCR and eGFR) for NAP226-90 following patch application, Table 5 (stratified by CLCR and eGFR) for rivastigmine, and Table 6 (stratified by CLCR and eGFR) for NAP226-90 following capsule administration. Results obtained using the body weight-adjusted concentrations for both rivastigmine and NAP226-90 (data not shown) were similar to those using body weight-unadjusted concentrations.

3.1 Patch

In this phase III study, 515 patients in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population received rivastigmine patch treatment. Steady-state plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 were available in 309 and 306 of these patients, respectively, and were used in the analysis. None of the analyzed patients had ESRD. When stratified by CLCR, two patients treated with the 20 cm2 (17.4 mg/24 h) patch and one patient treated with the 10 cm2 (9.5 mg/24 h) patch had severe renal impairment. When stratified by eGFR, there was one patient each in the 10 cm2 (9.5 mg/24 h) and 20 cm2 (17.4 mg/24 h) patch groups with severe renal impairment. The control group for the various patch sizes comprised patients with no (up to 25 %) or mild renal impairment.

Overall, the plasma concentrations for rivastigmine as well as NAP226-90 in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment were comparable with, or only slightly higher or lower than, those in patients with no or mild renal impairment. The boxplots largely overlapped for the two patients groups within each dose level.

The average changes in rivastigmine concentrations, depicted by the ratio of geometric means between the two patient groups when measured using CLCR, were −6, +22, +21, and +8 % for patch sizes 5 cm2 (4.6 mg/24 h), 10 cm2 (9.5 mg/24 h), 15 cm2 (13.3 mg/24 h), and 20 cm2 (17.4 mg/24 h), respectively (Table 3). The corresponding results for NAP226-90 were +12, +17, −23, and +10 %, respectively (Table 4).

When measured using eGFR, the average changes in rivastigmine concentrations between the two patient groups were +7, +21, and −40 % for patch sizes 5 cm2 (4.6 mg/24 h), 10 cm2 (9.5 mg/24 h), and 20 cm2 (17.4 mg/24 h), respectively (Table 3); the changes in NAP226-90 concentrations were +97, +8, and −10 %, respectively (Table 4). The ratio could not be estimated for rivastigmine and NAP226-90 following the 15 cm2 (13.3 mg/24 h) patch size as only one patient (i.e., eGFR value) was available in this dose group.

No correlations were observed between rivastigmine or NAP226-90 plasma concentrations and the baseline values of CLCR or eGFR as shown in the scatterplots for steady-state plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 against CLCR and eGFR in Fig. 3. The coefficients of correlation (R 2 values) calculated using linear regression to quantify the relationship between concentrations and CLCR or eGFR (i.e., to quantify the fraction of pharmacokinetic variation due to CLCR or eGFR) ranged from 0.1 to 2.5 %, confirming that neither CLCR nor eGFR have a clear effect on the exposure to rivastigmine or NAP226-90. The plasma concentrations of rivastigmine or NAP226-90 did not show any consistent trend of increasing with decreasing CLCR or eGFR values.

3.2 Capsule

Overall, 256 patients in the ITT population received the rivastigmine capsule formulation, and 234 of these patients completed the study. A total of 128 patients with steady-state plasma concentration of rivastigmine and/or NAP226-90 were included in the analysis. There were no patients with ESRD in the study population. Two patients treated with rivastigmine 12 mg/day had severe renal impairment when stratified by CLCR, but none had severe renal impairment when stratified by eGFR. The control group for the various capsule doses consisted of patients with no (up to 25 %) or mild renal impairment.

The plasma concentrations for both rivastigmine and NAP226-90 in patients with renal impairment were comparable to, or tended to be slightly lower (though some cases higher) than, those in the control group.

The average changes in rivastigmine concentrations, depicted by the ratio of geometric means between the two patient groups when measured using CLCR, were −16, −22, +8, and −15 % for daily doses of 3, 6, 9, and 12 mg, respectively (Table 5). The corresponding values for NAP226-90 were −21, −18, +31, and −6 %, respectively (Table 6).

When measured using eGFR, the average changes in rivastigmine concentrations between the two patient groups were +42, +20, −30, and +12 % for capsule daily doses 3, 6, 9, and 12 mg, respectively (Table 5); the changes in NAP226-90 concentrations were −19, +23, −40, and −3 %, respectively (Table 6).

No correlations were observed between plasma concentrations of either rivastigmine or NAP226-90 and baseline values of CLCR or eGFR as shown in scatterplots (Fig. 4). The coefficients of correlation (R 2 values) ranged from 0.1 to 2.4 %, confirming that neither CLCR nor eGFR have a clear effect on the exposure to rivastigmine or NAP226-90. The plasma concentrations of rivastigmine or NAP226-90 following capsule administration did not show any consistent trend of increasing with decreasing CLCR or eGFR values.

When the analysis was repeated with model-based estimates of plasma concentrations adjusted to a body weight of 65 kg, it yielded similar results for the body weight-adjusted concentrations to those obtained using the observed unadjusted concentrations (data not shown).

Overall, no consistent and relevant differences were observed in plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 in patients in the renal impairment group when compared with those in the control group.

4 Discussion

Medical co-morbidity is highest in the elderly, who constitute 6.4 % of the world’s population. These patients are on long-term multiple medication regimens for their co-morbidities and are the highest consumers of prescription medicines [27]. Polypharmacy increases the risk of medication-related adverse events, and advancing age is associated with alterations in drug pharmacokinetics. Renal impairment is more common in elderly patients, which increases the possibility of drug interactions, drug toxicity, and impaired drug elimination [28]. Elderly patients are more prone to adverse effects, leading to a decreased level of tolerance when compared with healthy individuals, and may require dose adjustment.

As previously demonstrated in a study exploring the ethnic differences in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the rivastigmine patch, urinary elimination of unchanged rivastigmine is low, amounting to a maximum of 4 % of the administered dose of rivastigmine [16]. Excretion of NAP226-90 was, at maximum, 20 % of the equivalent rivastigmine dose [16]. When administered via a transdermal patch, the amount of rivastigmine released from the device is known to increase linearly with the patch size, and the use of larger patch sizes translates into higher plasma exposure to rivastigmine [29]. This might have presented a concern for patients with compromised renal function, particularly at high doses, as the maximum concentration of drug in plasma (C max) and area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC) of rivastigmine increase more than proportionally with dose increments [16, 29, 30]. Similarly, for the capsule, the rivastigmine C max and AUC increased over-proportionally with dose increments [31]. The fact that rivastigmine (and NAP226-90) is poorly excreted in urine [16] means that, so far, there has been no need to conduct a specific study [19] in patients with renal impairment.

However, renal impairment can adversely affect some pathways of hepatic/gut drug metabolism and has also been associated with other changes (absorption, plasma protein binding, transport, and tissue distribution). These changes may be particularly prominent in patients with severely impaired renal function and have been observed even when the renal route is not the primary route of elimination of a drug. Thus, for most drugs that are likely to be administered to patients with renal impairment, including drugs that are not primarily excreted by the kidney, it is strongly recommended, including by the FDA [18], that the pharmacokinetics in patients with renal impairment be investigated to provide appropriate dosing recommendations. Even though rivastigmine and NAP226-90 are poorly excreted in urine, the true effect of renal impairment on pharmacokinetic is unclear and has raised the interest of health authorities and practitioners.

The present pharmacokinetic analyses of rivastigmine and its inactive metabolite NAP226-90 following patch and capsule administration in AD patients showed that the steady-state plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 were comparable between the control and renal impairment groups. This is a reassuring finding indicating no safety or efficacy concerns with the use of rivastigmine patch or capsule in patients with impaired renal function. The plasma concentrations of both rivastigmine and NAP226-90 largely overlapped between patient groups within each dose level of patch or capsule when renal function was measured using either CLCR or eGFR.

Changes in rivastigmine concentrations (determined by the ratio of geometric means) between the two groups were small and considered to be not clinically relevant when renal impairment was stratified by CLCR or eGFR. Moreover, decreasing CLCR or eGFR values were not associated with a systematic one-way change (e.g., systematic increase) in plasma concentrations of rivastigmine or NAP226-90. The distribution and fluctuation (increase or decrease) of the observed steady-state plasma concentrations after administration of rivastigmine were comparable between the renal impairment patients and the control group for both analytes. The same analysis when using the body weight-adjusted concentrations of rivastigmine or NAP226-90 resulted in the same findings and conclusions as those with the body weight-unadjusted observations, except for effects due to the small patient numbers in the 5 cm2 (4.6 mg/24 h) and 15 cm2 (13.3 mg/24 h) patch groups. In addition, the plasma concentrations of rivastigmine and NAP226-90 did not show any clear or consistent trend between the two patient groups who were administered capsules. Therefore, no dose adjustment for patch or capsule formulations is required in patients with renal impairment.

Other drugs available to treat AD such as memantine, galantamine and donepezil are excreted unchanged by the renal route. Dose restriction is advised with memantine, which is excreted predominantly in urine as unchanged drug, in part via renal tubular secretion among patients with severe renal impairment [32]. Although pharmacokinetic interactions between memantine and other renally excreted drugs have not been observed [32], drugs excreted mainly by the renal route can pose a risk from interaction with other concomitantly administered renally excreted drugs in a patient with a limited renal reserve. Galantamine is excreted unchanged in urine, representing approximately 20–25 % of the administered dose. As observed with memantine, exposures to galantamine in patients with moderate and severe renal impairment are higher than those observed in healthy subjects [33]. Donepezil, another acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, undergoes significant first-pass metabolism and 16.9 % of the administered dose is excreted unchanged in urine [34]. Plasma concentrations of donepezil were found to be numerically but not significantly higher in patients with renal impairment relative to the healthy controls [35]. However, a relationship trend between exposure parameters (in particular AUC) and CLCR was observed. Another study of donepezil extended these findings to steady-state concentrations [36]. On the contrary, rivastigmine administered as both patch and capsule formulations shows insignificant renal excretion and there was no correlation between its systemic exposure and renal function status.

The present analysis is useful in guiding the dose decisions for rivastigmine in patients with compromised renal function as it shows that patients with renal impairment can be administered rivastigmine at dosages similar to those administered to patients with normal renal function, and the dosing should be guided by disease stage and patient tolerability to ensure optimal therapeutic dosing.

5 Conclusions

Renal function, as measured by CLCR or eGFR, does not impact the steady-state plasma concentrations of either rivastigmine or its inactive metabolite NAP226-90. The concentrations of both rivastigmine and NAP226-90 in patients with AD treated with rivastigmine patch 5 cm2 (4.6 mg/24 h), 10 cm2 (9.5 mg/24 h), 15 cm2 (13.3 mg/24 h), and 20 cm2 (17.4 mg/24 h) or capsule (3, 6, 9, and 12 mg/day) were comparable between the control and impaired renal function groups, indicating that patients with renal impairment can be administered rivastigmine at dosages similar to those administered to patients with normal renal function.

References

Bird TD. Genetic aspects of Alzheimer disease. Genet Med. 2008;10:231–9.

Rao AT, Degnan AJ, Levy LM. Genetics of Alzheimer disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:457–8.

Bell JS, Blacker N, Leblanc VT, Alderman CP, Phillips A, Rowett D, et al. Prescribing for older people with chronic renal impairment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42:24–8.

Rowe JW, Andres R, Tobin JD, Norris AH, Shock NW. The effect of age on creatinine clearance in men: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. J Gerontol. 1976;31:155–63.

Glassock RJ. The GFR decline with aging: a sign of normal senescence, not disease. Nephrol Times. 2009;9:6–8.

Farlow M, Anand R, Messina J Jr, Hartman R, Veach J. A 52-week study of the efficacy of rivastigmine in patients with mild to moderately severe Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Neurol. 2000;44(4):236–41.

Rosler M, Anand R, Cicin-Sain A, Gauthier S, Agid Y, Dal-Bianco P, et al. Efficacy and safety of rivastigmine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: international randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999;318:633–8.

Karaman Y, Erdogan F, Koseoglu E, Turan T, Ozdemir Ersoy A. A 12-month study of the efficacy of rivastigmine in patients with advanced moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19:51–6.

Emre M, Aarsland D, Albanese A, Byrne EJ, Deuschl G, De Deyn PP, et al. Rivastigmine for dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2509–18.

Onor ML, Trevisiol M, Aguglia E. Rivastigmine in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: an update. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2:17–32.

Finkel SI. Effects of rivastigmine on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Ther. 2004;26:980–90.

Farlow MR, Cummings JL, Olin JT, Meng X. Effects of oral rivastigmine on cognitive domains in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25:347–52.

Burns A, Spiegel R, Quarg P. Efficacy of rivastigmine in subjects with moderately severe Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:243–9.

Cutler NR, Polinsky RJ, Sramek JJ, Enz A, Jhee SS, Mancione L, et al. Dose-dependent CSF acetylcholinesterase inhibition by SDZ ENA 713 in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 1998;97:244–50.

Kennedy JS, Polinsky RJ, Johnson B, Loosen P, Enz A, Laplanche R, et al. Preferential cerebrospinal fluid acetylcholinesterase inhibition by rivastigmine in humans. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:513–21.

Lefèvre G, Buche M, Sedek G, Maton S, Enz A, Lorch U, et al. Similar rivastigmine pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in Japanese and white healthy participants following the application of novel rivastigmine patch. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:430–43.

Spencer CM, Noble S. Rivastigmine: a review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging. 1998;13:391–411.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Pharmacokinetics in patients with impaired renal function—study design, data analysis, and impact on dosing and labeling. 2010. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/…/Guidances/UCM204959.pdf. Accessed 2 Nov 2015.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Population pharmacokinetics. 1999. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM072137.pdf. Accessed 2 Nov 2015.

Lefèvre G, Pommier F, Sedek G, Allison M, Huang HL, Kiese B, et al. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of the novel rivastigmine transdermal patch versus rivastigmine oral solution in healthy elderly subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48:246–52.

Winblad B, Cummings J, Andreasen N, Grossberg G, Onofrj M, Sadowsky C, et al. A six-month double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of a transdermal patch in Alzheimer’s disease–rivastigmine patch versus capsule. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:456–67.

Winblad B, Grossberg G, Frolich L, Farlow M, Zechner S, Nagel J, et al. IDEAL: a 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the first skin patch for Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;69(4 Suppl 1):S14–22.

Pommier F, Frigola R. Quantitative determination of rivastigmine and its major metabolite in human plasma by liquid chromatography with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B. 2003;784:301–13.

Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12.

Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function–measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473–83.

Bushardt RL, Massey EB, Simpson TW, Ariail JC, Simpson KN. Polypharmacy: misleading, but manageable. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:383–9.

Yong TY, Lau SY, Li JY, Hakendorf P, Thompson CH. Medication prescription among elderly patients admitted through an acute assessment. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12:93–101.

Lefèvre G, Sedek G, Jhee SS, Leibowitz MT, Huang HL, Enz A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the novel daily rivastigmine transdermal patch compared with twice-daily capsules in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:106–14.

Zhang L, Xu N, Xiao S, Arya V, Zhao P, Lesko LJ, et al. Regulatory perspectives on designing pharmacokinetic studies and optimizing labeling recommendations for patients with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(1 Suppl):79S–90S.

Hossain M, Jhee SS, Shiovitz T, McDonald C, Sedek G, Pommier F, et al. Estimation of the absolute bioavailability of rivastigmine in patients with mild to moderate dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41:225–34.

Periclou A, Ventura D, Rao N, Abramowitz W. Pharmacokinetic study of memantine in healthy and renally impaired subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:134–43.

Huang F, Fu Y. A review of clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of galantamine, a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, in healthy subjects and patients. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2010;5:115–24.

Tiseo PJ, Perdomo CA, Friedhoff LT. Metabolism and elimination of 14C-donepezil in healthy volunteers: a single-dose study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:19–24.

Tiseo PJ, Foley K, Friedhoff LT. An evaluation of the pharmacokinetics of donepezil HCl in patients with moderately to severely impaired renal function. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:56–60.

Nagy CF, Kumar D, Cullen EI, Bolton WK, Marbury TC, Gutierrez MJ, et al. Steady-state pharmacokinetics and safety of donepezil HCl in subjects with moderately impaired renal function. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58(1 Suppl):18–24.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Aditi Kataria and Hemant Kumar Mittal of Novartis Healthcare Pvt. Ltd. for their writing and editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of interest

Gilbert Lefèvre and Francesca Callegari are employees of Novartis and as such may be eligible for Novartis stock and stock options. Sandro Gsteiger and Yuan Xiong were employees of Novartis at the time of the research and analysis and as such may have been eligible for Novartis stock and stock options. None of the authors are Fellows of the American College of Clinical Pharmacology (FCP).

Research Involving Human Participants

The protocol, informed consent form, any amendments, and other information given to patients and caregivers were reviewed by an Institutional Review Board or Independent Ethics Committee for each center. The study was conducted according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2000.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lefèvre, G., Callegari, F., Gsteiger, S. et al. Effects of Renal Impairment on Steady-State Plasma Concentrations of Rivastigmine: A Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Capsule and Patch Formulations in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Drugs Aging 33, 725–736 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-016-0405-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-016-0405-y