Abstract

Diacerein is a symptomatic slow-acting drug in osteoarthritis (SYSADOA) with anti-inflammatory, anti-catabolic and pro-anabolic properties on cartilage and synovial membrane. It has also recently been shown to have protective effects against subchondral bone remodelling. Following the end of the revision procedure by the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee of the European Medicines Agency, the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) constituted a panel of 11 experts to better define the real place of diacerein in the armamentarium for treating OA. Based on a literature review of clinical trials and meta-analyses, the ESCEO confirms that the efficacy of diacerein is similar to that of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) after the first month of treatment, and superior to that of paracetamol. Additionally, diacerein has shown a prolonged effect on symptoms of several months once treatment was stopped. The use of diacerein is associated with common gastrointestinal disorders such as soft stools and diarrhoea, common mild skin reactions, and, uncommonly, hepatobiliary disorders. However, NSAIDs and paracetamol are known to cause potentially severe hepatic, gastrointestinal, renal, cutaneous and cardiovascular reactions. Therefore, the ESCEO concludes that the benefit–risk balance of diacerein remains positive in the symptomatic treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Furthermore, similarly to other SYSADOAs, the ESCEO positions diacerein as a first-line pharmacological background treatment of osteoarthritis, particularly for patients in whom NSAIDs or paracetamol are contraindicated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Randomised clinical trials show that diacerein has a similar efficacy compared with NSAIDs on osteoarthritis symptoms. |

Diacerein has an acceptable safety profile, particularly in comparison with that of NSAIDs and paracetamol. |

The ESCEO positions diacerein as a first-line pharmacological background treatment of osteoarthritis. |

1 Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most frequent form of arthritis, and one of the leading causes of disability among older adults worldwide [1]. For individuals, the burden of OA also includes persistent background pain (aching) and intermittent but generally more intense pain. Together with disability, pain contributes to a significant reduction in quality of life.

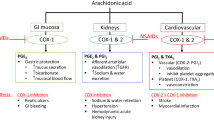

The management of OA includes pharmacological therapies, which are mostly symptomatic [2]. Paracetamol is the first-line oral analgesic, whilst oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, are the mainstay of therapy [3, 4]. These drugs are considered as rapid-acting drugs in OA and are recommended by rheumatology societies [2, 5, 6] and government agencies [7].

Symptomatic slow-acting drugs for OA (SYSADOAs) such as glucosamine, chondroitin sulphate and diacerein are used for non-acute treatment. Although there is relative general agreement on many OA management recommendations across organisations, there is still no consensus on the place of SYSADOAs. In general, they are considered supplementary to analgesics and NSAIDs, whereas the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) places SYSADOAs as pharmacological background treatment; that is, first chronic therapy that may improve or control symptoms [8].

Diacerein is an anthraquinone derivative, of which the active metabolite is rhein. Its positioning in the algorithm established by the ESCEO [8] had not been formalised because, at the time of publication, diacerein was under review by the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Following the assessment of the PRAC, the ESCEO felt the need to evaluate the role of diacerein in clinical practice and constituted a panel of experts to define its place in the management of OA. This article expresses the reasoned conclusions drawn by the ESCEO working group on diacerein.

2 ESCEO Working Group Process

The ESCEO invited 11 experts in musculoskeletal diseases (rheumatologists, clinical epidemiologists and scientists) to be part of the working group. Four members had already been involved in clinical or preclinical research on diacerein, two of them being current diacerein prescribers; all were proficient in analysing and interpreting clinical trial evidence related to OA.

Five of the participants were entrusted with the task of preparing a review on the mode of action, efficacy and safety of diacerein in the treatment of OA. A literature search was conducted in May 2015 using the MEDLINE/PubMed database. The search strategy included a combination of the following terms: ‘diacerein’, ‘diacetylrhein’, ‘diacerhein’, ‘rhein’ and ‘osteoarthritis’. Filter settings were ‘English’, ‘French’, ‘German’, ‘Spanish’ or ‘Italian’ languages. This literature search yielded 179 hits, of which 108 (57 original research papers, 51 reviews, meta-analyses or opinion-based articles) were retrieved according to their relevance to the topics mentioned above: 42 were related to the mode of action of diacerein, 60 dealt with its clinical efficacy, and 45 contained information on the safety of diacerein. Additional references were selected from the reference lists of the retrieved articles to broaden the literature search.

The outcome of this review was finally discussed by the 11 experts at a one-day meeting in June 2015.

3 The Mechanism of Action of Diacerein in Osteoarthritis

3.1 In Vitro Studies

The principal mechanism of action of diacerein is to inhibit the interleukin-1β (IL-1β) system and related downstream signalling [9]. Diacerein has been shown to impact the activation of IL-1β via a reduced production of IL-1 converting enzyme [10], as well as to affect the sensitivity to IL-1 by decreasing IL-1 receptor levels on the cell surface of chondrocytes [11] and by indirectly increasing IL-1 receptor antagonist production [12, 13]. Production of IL-1β may also be affected, as diacerein has been shown to inhibit the IL-1β-induced activation of transcription factor NF-κB, which stimulates pro-inflammatory cytokine expression [14–16]. Downregulation of IL-1 levels has been confirmed in the synovial fluid of patients with knee OA [17].

Besides its anti-inflammatory properties, diacerein has been shown to have anti-catabolic [15, 16] and pro-anabolic [15, 18–20] effects on cartilage and synovial membrane, as well as protective effects against subchondral bone remodelling (Table 1) [21].

3.2 Animal Models of Osteoarthritis

Beneficial effects of diacerein on cartilage and subchondral bone have been observed in various animal models of OA. Diacerein consistently reduced cartilage loss compared with untreated controls [26–30], improved cartilage lesions in the experimental hip chondrolysis model of immature Beagle dogs [31], and induced an increase in bone mineral density as well as a decrease in the thickness of the subchondral bone plate [28]. Finally, prophylactic treatment with diacerein has been shown to delay arthritis secondary to meniscectomy in a rat model of OA [32].

4 Clinical Data on the Efficacy of Diacerein

4.1 Effects on Pain and Physical Function

Efficacy of diacerein was evaluated in 16 published clinical trials [33–48]. Patients included in these studies were representative of patients in a real-life setting, so that the outcomes can be extrapolated to the general population.

Four published meta-analyses assessed the symptomatic effects of 100 mg/day diacerein [49–52]. Each of them included a different set of clinical studies (Table 2).

In a meta-analysis of 19 published and unpublished studies including a total of 2637 patients, Rintelen and co-authors [49] showed a statistically significant superiority of diacerein over placebo at the end of treatment with respect to pain reduction and physical function improvement. At the end of the treatment-free follow-up period, diacerein was also found to be significantly better than placebo on pain (no pooled data on function), thus demonstrating a carry-over effect after stopping treatment. When compared with standard treatments (mostly NSAIDs), no statistically significant difference regarding pain and physical function was observed at the end of the treatment period. However, at the end of the treatment-free follow-up period, pooled Glass’ standardised mean differences on pain and joint function showed that diacerein was significantly superior over the active comparator (Fig. 1).

Comparison of diacerein vs placebo (a) and diacerein vs active comparator (mostly NSAIDs) (b) regarding pain and physical function at the end of the active treatment period, as well as after the treatment-free follow-up period (dechallenge) (Rintelen et al. [49] meta-analysis). Error bars indicate 95 % confidence intervals. Glass’ standardised mean differences greater than 0.8 are commonly regarded as clinically relevant

Using the strict Cochrane criteria for meta-analyses, Fidelix and co-authors reviewed seven published randomised controlled trials in a total of 2069 patients with OA [50]. Three more clinical trials [44, 45, 47] were included in the updated Cochrane Review [51] compared with the 2006 version. The main differences in outcomes between the two meta-analyses are shown in Table 3. Thus, in the Cochrane 2014 version, the mean-weighted differences (MWD) tended to increase in favour of diacerein compared with placebo. The authors concluded that diacerein had a small but significant effect on overall pain after 3–36 months of treatment. In addition, results of a subgroup analysis demonstrating a carry-over effect of diacerein compared with placebo or NSAIDs on pain and physical function were presented.

Finally, another meta-analysis on randomised, placebo-controlled trials with diacerein was published by Bartels et al. [52]. The authors included six studies with a total of 1533 patients. The effect size (ES) was estimated using Hedges’ standardised mean difference. For pain reduction, results showed that the combined ES was −0.24 (95 % CI −0.39 to −0.08, p = 0.003, I 2 = 56 %), favouring diacerein. There was also a statistically significant improvement in physical function (p = 0.01, I 2 = 11 %).

4.2 Structure-Modifying Effects

Two clinical studies assessed the impact of diacerein on radiological signs of OA: one was conducted in patients with hip OA [40], the other in patients with knee OA [41].

The ECHODIAH (Evaluation of the Structure-Modifying Effects of Diacerein in Hip Osteoarthritis) study [40] was a 3-year, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the potential structure-modifying effects of diacerein in 507 patients with painful and structurally advanced primary hip OA. Sixty-one patients did not have any pelvic X-ray after the start of treatment and were therefore excluded from the analysis.

The between-group comparison in the number of patients with a joint space narrowing (JSN) of at least 0.5 mm showed a statistically significant difference in favour of diacerein in both the intent-to-treat (ITT) and the Completer analyses (primary populations of analysis). The between-group comparison in JSN rate also showed a statistically significant difference in the Completer analysis, while no difference was observed in the ITT population using the last-observation-carried-forward imputation method. Results in the per protocol (PP) population (secondary analysis) were similar to those in the Completer data set (Table 4).

The above results in the ECHODIAH study demonstrated the superiority of diacerein treatment versus placebo in only three of four co-primary endpoints for JSN and failed to demonstrate the structure-modifying effects of diacerein in patients with hip OA.

The Pham study (2004) [41] was conducted in 301 patients with knee OA. The aim of this 1-year, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, three-arm trial was to evaluate the long-term efficacy of three cycles of 3-weekly intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid (HA) in the treatment of symptomatic knee OA compared with oral diacerein and placebo. A saline solution was used in the diacerein and placebo groups to maintain the blind.

No statistically significant differences between groups were observed for JSN. The percentage of patients with a progression >0.5 mm was 17.7, 18.9 and 20.3 % (p = 0.90) in the HA, diacerein and placebo groups, respectively.

5 Clinical Data on the Safety of Diacerein

5.1 Gastrointestinal

Regarding the risk of gastrointestinal disorders, the most frequently reported events with diacerein were loose stools and diarrhoea. The laxative effect of diacerein is well known and results from its anthraquinone chemical structure.

Bartels et al. [52] calculated that the risk ratio (RR) for developing diarrhoea under diacerein versus placebo treatment was 3.51 (95 % CI 2.55–4.83). Fidelix et al. [51] obtained an RR of 3.52 (95 % CI 2.42–5.11) for diacerein versus placebo, with an absolute risk increase of 24 % (95 % CI 12–35). Well in line with these meta-analyses, Rintelen and co-authors [49] summarised that 39 % of patients treated with diacerein versus 12 % of patients receiving placebo experienced at least one episode of loose stool or diarrhoea.

Diarrhoea was mentioned to be generally mild to moderate in all publications that make reference to the severity [35, 40, 44], and occurred in the first 2 weeks of treatment. No particular pattern of associated disorders could be detected. In all cases, the diacerein-induced diarrhoea was reversible after cessation of treatment. Furthermore, diarrhoeal symptoms decreased in most cases after continuous treatment [62].

The post-marketing surveillance of diacerein showed that 25 serious cases of diarrhoea were reported. Three of them concerned elderly patients, who experienced dehydration and electrolyte disorders; one case was fatal and occurred in a 79-year-old female with a medical history of arterial hypertension and cardiac arrhythmia [63].

5.2 Cutaneous

The skin was not a target organ for toxicity in short- and long-term animal toxicology studies. Nevertheless, the incidence of cutaneous events in the 15 published clinical trials evaluating diacerein ranged between 1.8 % [35, 36] and 9.4 % [41]. The present review identified rash, pruritus and eczema as the most common cutaneous reactions reported in clinical trials. They are appropriately reflected in the product information with a frequency of >1/100 and <1/10).

Furthermore, the available post-marketing data revealed a few severe cases of cutaneous events: four erythema multiform, two Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and three toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) [63].

5.3 Hepatic

Among the 15 published clinical trials evaluating diacerein, only Zheng et al. [43] reported the occurrence of a hepatic adverse event: one treatment discontinuation due to increase in hepatic enzymes. The PRAC performed a more complete analysis of available data and retrieved seven clinical trials showing abnormalities of liver tests. These were mostly characterised by mild/moderate liver enzyme increase (ALT, AST <5 ULN) without increases in bilirubin [63].

A total of 89 cases within the post-marketing surveillance were considered as hepatic reactions. The most frequent reactions were liver function test abnormalities (41 cases) [63]. One case of hepatic failure had a fatal outcome and a close temporal association with diacerein [64].

The extensive preclinical animal toxicology data with diacerein indicated that the liver was not a target organ for toxicity. The mechanism of action of this hepatic toxicity is not fully understood, but an idiosyncratic mechanism is suggested.

5.4 Cardiovascular

Diacerein does not appear to show cardiovascular toxicity. Indeed, a toxicology study designed in accordance with ICH S7A guidelines demonstrated that diacerein at 5 and 30 mg/kg/day for 7 consecutive days, and at 60 and 200 mg/kg/day for 4 and 3 consecutive days, respectively, did not affect the cardiovascular system in the conscious dog [65]. The doses used in this study were between 3.6 times and about 143 times the recommended dose in humans (1.4 mg/kg/day based on a 70 kg person).

More significantly, no signal from post-marketing surveillance for acute coronary syndromes or myocardial infarctions was reported in more than 20 years of experience with diacerein.

6 Discussion

The overall analysis of randomised controlled clinical studies and meta-analyses confirmed the efficacy of diacerein in the symptomatic treatment of knee and hip OA. An ES on pain of 0.24 (95 % CI 0.08–0.39) has been reported [52], a value considered to be low but clinically relevant in OA [66]. Furthermore, as the ES of diacerein and other anti-OA agents is based on the difference between the placebo and the active drug effects, it is relevant to note that unequivocal evidence for a large placebo response has been demonstrated in randomised clinical trials of OA (ES = 0.51, 95 % CI 0.46–0.55) [67]. The ES of diacerein should therefore be assessed bearing in mind this large placebo response.

Although NSAIDs have shown a more rapid onset of action than diacerein, efficacy of these drugs on pain and joint function was comparable after the first month of treatment. On the other hand, unlike NSAIDs, diacerein has shown a prolonged effect of several months once treatment was stopped. Evidence published by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) indicated that diacerein had a greater efficacy on pain reduction in OA than paracetamol (ES = 0.14, 95 % CI 0.05–0.22), and a similar efficacy compared with NSAIDs (ES = 0.29, 95 % CI 0.22–0.35) [6].

The use of diacerein is associated with common gastrointestinal disorders (mostly soft stools and diarrhoea), common mild skin reactions, and uncommon hepatobiliary disorders. Frequent cases of severe diarrhoea and rare cases of potentially serious hepatotoxicity were reported; a risk of cutaneous drug reactions could not be excluded [63].

In order to minimise this risk, it is recommended to start diacerein treatment with half the recommended dose (50 mg/day) for the first 2–4 weeks, the laxative properties of diacerein being dose-dependent [39]. In the same context, starting a treatment with diacerein is not recommended in patients older than 65 years who are considered to be more vulnerable to diarrhoeal complications [68]. In parallel, laxatives should be avoided, and concomitant treatment with medicines that can lead to hypokalaemia should be especially monitored. Finally, it is common sense to stop treatment as soon as diarrhoea occurs. To prevent the risk of hepatotoxicity, diacerein is contraindicated in patients with current or a history of liver disease and, therefore, patients should be screened for major causes of active hepatic disease before starting the treatment. Caution should be exercised when diacerein is used concomitantly with products associated with hepatic injury. Treatment should be stopped if elevation of hepatic enzymes or suspected signs or symptoms of liver damage are detected.

Safety of diacerein should be put in the context of paracetamol and NSAID use, drugs that have been shown to cause potentially severe hepatic [69–71], gastrointestinal [72, 73], renal [74–77], cutaneous [78] and cardiovascular reactions [79–82]. For example, an incidence of clinically apparent liver injuries of 10.0 per 100,000 patient-years of treatment with NSAIDs has been reported [83], and paracetamol is responsible for the higher rate of hospitalisations for hepatic failures [69]. In comparison, the risk of hepatic disorders with diacerein (including elevated hepatic enzymes) was 1.68 per 100,000 patient-years of treatment. Regarding cutaneous reactions, NSAIDs have been reported to be the second most common cause of drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction [84], and among the drugs that are the most frequently associated with SJS and TEN [85]. NSAIDs are also known for increasing the risk of cardiovascular events, including congestive heart failure and infarction/stroke [73, 86, 87].

Several rheumatology societies, such as the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) [2] and the OARSI [5, 6], have included diacerein in their therapeutic guidelines as a treatment option in OA. However, a review evaluating the benefit–risk ratio of diacerein conducted by the PRAC was initiated in November 2012 following the request of the French Medicines Agency. One year later, the PRAC/EMA initially recommended the suspension of the marketing authorisations for diacerein, but following re-examination, additional proposals to manage the risks of diacerein were considered. As a result, in July 2014, the PRAC/EMA confirmed the safety profile of diacerein, which has not changed in 20 years, and concluded that its benefit–risk balance remained positive in the symptomatic treatment of hip and knee OA [63].

Based on the opinion of 11 experts in rheumatology, the ESCEO working group underlines the PRAC/EMA conclusions that the benefits of diacerein outweigh its risks and confirms that diacerein is an interesting option in the physician’s armamentarium for treating OA. These conclusions are also in line with those of a review recently published by two independent Australian experts [88]. Therefore, similarly to other SYSADOAs, the ESCEO positions diacerein as a first-line background pharmacological treatment of OA. However, it should be avoided in patients with a known propensity for diarrhoea, but would be particularly beneficial in patients with contraindications to NSAIDs or paracetamol.

Diacerein is a compound with a long history but whose effects are still not fully understood. Besides the evidence of its efficacy in knee and hip OA, there are very few data on its effect in other OA locations such as the hand, as well as on different types of patient profiles [89], or OA subtypes. Further research also needs to be performed to define the real potential of diacerein on disease progression with well designed, high quality, structure-modifying clinical trials. Then, depending on the outcomes on cartilage and knowing the proven carry-over therapeutic effect of diacerein, one might question whether continuous or intermittent treatment would be the most reasonable.

References

Hunter DJ, Schofield D, Callander E. The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(7):437–41.

Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, Bannwarth B, Bijlsma JW, Dieppe P, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: Report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(12):1145–55.

Jones AC, Doherty M. The treatment of osteoarthritis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;33(4):357–63.

Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J. Therapeutic targets in osteoarthritis: from today to tomorrow with new imaging technology. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62 (Suppl 2):ii79–ii82.

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22:363–88 (Comment in: Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(6):888–9; author’s reply 890–1; Corrigendum in: Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23(6):1026–34).

Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden NK, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(4):476–99.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NHS). Osteoarthritis: the care and management of osteoarthritis in adults. In: NICE clinical guideline 59. 2008. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG059. Accessed 1 Feb 2013.

Bruyere O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, Branco J, Luisa Brandi M, Guillemin F, et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: a report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(3):253–63.

Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP. Effects of diacerein at the molecular level in the osteoarthritis disease process. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2010;2(2):95–104.

Moldovan F, Pelletier JP, Jolicoeur FC, Cloutier JM, Martel-Pelletier J. Diacerhein and rhein reduce the ICE-induced IL-1 beta and IL-18 activation in human osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2000;8:186–96.

Martel-Pelletier J, Mineau F, Jolicoeur FC, Cloutier JM, Pelletier JP. In vitro effects of diacerhein and rhein on interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha systems in human osteoarthritic synovium and chondrocytes. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(4):753–62.

Pelletier JP, Mineau F, Ranger P, Tardif G, Martel-Pelletier J. The increased synthesis of inducible nitric oxide inhibits IL-1ra synthesis by human articular chondrocytes: possible role in osteoarthritic cartilage degradation. Osteoarthr Cartil. 1996;4(1):77–84.

Yaron M, Shirazi I, Yaron I. Anti-interleukin-1 effects of diacerein and rhein in human osteoarthritic synovial tissue and cartilage cultures. Osteoarthr Cartil. 1999;7(3):272–80.

Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(15):1066–71.

Martin G, Bogdanowicz P, Domagala F, Ficheux H, Pujol JP. Rhein inhibits interleukin-1beta-induced activation of MEK/ERK pathway and DNA binding of NF-kappaB and AP-1 in chondrocytes cultured in hypoxia: a potential mechanism for its disease-modifying effect in osteoarthritis. Inflammation. 2003;27(4):233–46.

Ferreira Mendes A, Caramona MM, de Carvalho AP, Lopes MC. Diacerhein and rhein prevent interleukin-1 beta-induced nuclear factor-kappa B activation by inhibiting the degradation of inhibitor kappa B-alpha. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;91(1):22–8.

Mathieu P. L’interleukine 1: son role, son dosage, ses difficultés d’approche dans l’arthrose. Résultats d’une étude ‘pilote ‘ avec la diacerhéine (ART 50) dans la gonarthrose [Interleukin 1 its role, quantitative determination and the difficulties in studying its role in osteoarthritis. Results of a ‘pilot’ study with diacerein (ART 50) in knee osteoarthritis]. Rev Prat. 1999;49(Suppl 13):S15–8. French.

Felisaz N, Boumediene K, Ghayor C, Herrouin JF, Bogdanowicz P, Galerra P, et al. Stimulating effect of diacerein on TGF beta 1 and beta 2 expression in articular chondrocytes cultured with and without interleukin-1. Osteoarthr Cartil. 1999;7(3):255–64.

Sanchez C, Mathy-Hartert M, Deberg MA, Ficheux H, Reginster JY, Henrotin YE. Effects of rhein on human articular chondrocytes in alginate beads. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65(3):377–88.

Schöngen RN, Giannetti BM, Van de Leur E, Reinards R, Greiling H. Effect of diacetylrhein on the phagocytosis of polymorphonuclear leucocytes and its influence on the biosynthesis of hyaluronate in synovial cells. Arzneimittelforschung. 1988;38(I)(5):744–8.

Pelletier JP, Lajeunesse D, Reboul P, Mineau F, Fernandes JC, Sabouret P, et al. Diacerein reduces the excess synthesis of bone remodeling factors by human osteoblast cells from osteoarthritic subchondral bone. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(4):814–24.

Legendre F, Bogdanowicz P, Martin G, Domagala F, Leclercq S, Pujol JP, et al. Rhein, a diacerhein-derived metabolite, modulates the expression of matrix degrading enzymes and the cell proliferation of articular chondrocytes by inhibiting ERK and JNK-AP-1 dependent pathways. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(4):546–55.

Pelletier JP, Mineau F, Fernandes JC, Duval N, Martel-Pelletier J. Diacerhein and rhein reduce the interleukin 1 beta stimulated inducible nitric oxide synthesis level and activity while stimulating cyclooxygenase-2 synthesis in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(12):2417–24.

Martel-Pelletier J, Mineau F, Caron J, Pelletier JP. Effect of diacerein/rhein on the Wnt system in human osteoarthritic subchondral bone [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(Suppl 3):354 (Abstract no. FRI0025).

Boileau C, Tat SK, Pelletier JP, Cheng S, Martel-Pelletier J. Diacerein inhibits the synthesis of resorptive enzymes and reduces osteoclastic differentiation/survival in osteoarthritic subchondral bone: a possible mechanism for a protective effect against subchondral bone remodelling. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(3):R71.

Brandt KD, Smith G, Kang SY, Myers S, O’Connor B, Albrecht M. Effects of diacerhein in an accelerated canine model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 1997;5:438–49.

Smith GN Jr, Myers SL, Brandt KD, Mickler EA, Albrecht ME. Diacerhein treatment reduces the severity of osteoarthritis in the canine cruciate-deficiency model of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(3):545–54.

Ghosh P, Xu A, Hwa SY, Burkhardt D, Little C. Evaluation des effets de la diacerhéine dans un modele ovin d’arthrose [Evaluation of the effects of diacerhein in an ovine model of osteoarthritis]. Rev Prat. 1998;48(Suppl 17):S24–30. French.

Bendele AM, Bendele RA, Hulman JF, Swann BP. Effets bénéfiques d’un traitement par la diacerhéine chez des cobayes atteints d’arthrose [The beneficial effects of diacerein treatment in a guinea pig model of osteoarthritis]. Rev Prat. 1996;46:S35–9. French.

Mazieres B, Berda L. Effect of diacerheine (ART 50) on an experimental post-contusive model of OA. Osteoarthr Cartil. 1993;1(1):47.

Kitadai HK, Takahashi HK, Straus AH, Ibanez JF, Lucas R, Kitadai FT, et al. Effect of oral diacerein (DAR) in an experimental hip chondrolysis model. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(6):1240–8.

de Rezende MU, de Campos Gurgel HM, Vilaca Junior PR, Kuroba RK, Lopes AS, Phillipi RZ, et al. Diacerhein versus glucosamine in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Clinics. 2006;61(5):461–6.

Marcolongo R, Fioravanti A, Adami S, Tozzi E, Mian M, Zampieri A. Efficacy and tolerability of Diacerhein in the treatment of osteoarthrosis. Curr Ther Res. 1988;43(5):878–87.

Nguyen M, Dougados M, Berdah L, Amor B. Diacerhein in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(4):529–36.

Delcambre B, Taccoen A. Etude d’ART 50 en pratique rhumatologique quotidienne [Study of ART 50 in daily rheumatological practice]. Rev Prat. 1996;46(6 Spec No):S49–S52. French.

Fagnani F, Bouvenot G, Valat JP, Bardin T, Berdah L, Lafuma A, et al. Medico-economic analysis of diacerein with or without standard therapy in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;13(1 Pt 2):135–46.

Lequesne M, Berdah L, Gérentes I. Efficacité et tolérance de la diacerhéine dans le traitement de la gonarthrose et de la coxarthrose [Efficacy and tolerance of diacerhein in the treatment of gonarthrosis and coxarthrosis]. Rev Prat. 1998;48(Suppl 17):S31–5. French.

Chantre P, Cappelaere A, Leblan D, Guedon D, Vandermander J, Fournie B. Efficacy and tolerance of Harpagophytum procumbens versus diacerhein in treatment of osteoarthritis. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(3):177–83.

Pelletier JP, Yaron M, Haraoui B, Cohen P, Nahir MA, Choquette D, et al. Efficacy and safety of diacerein in osteoarthritis of the knee: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Diacerein Study Group. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(10):2339–48.

Dougados M, Nguyen M, Berdah L, Mazieres B, Vignon E, Lequesne M. Evaluation of the structure-modifying effects of diacerein in hip osteoarthritis: ECHODIAH, a three-year, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(11):2539–47.

Pham T, Le Henanff A, Ravaud P, Dieppe P, Paolozzi L, Dougados M. Evaluation of the symptomatic and structural efficacy of a new hyaluronic acid compound, NRD101, in comparison with diacerein and placebo in a 1 year randomised controlled study in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(12):1611–7.

Jayaram S, Shetty N, Krishnamurthy V, Sharma VD, Naik MN, Apsangikar PD. Clinical study of the efficacy and tolerability of diacerein in the treatment of mild to moderate osteoarthritis: a randomized, multicentre, comparative study. Indian Pract. 2005;58(11):683–91.

Zheng WJ, Tang FL, Li J, Zhang FC, Li ZG, Su Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of diacerein in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, multicenter, double-dummy, diclofenac-controlled trial in China. APLAR J Rheumatol. 2006;9(1):64–9.

Pavelka K, Trc T, Karpas K, Vitek P, Sedlackova M, Vlasakova V, et al. The efficacy and safety of diacerein in the treatment of painful osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with primary end points at two months after the end of a three-month treatment period. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(12):4055–64.

Louthrenoo W, Nilganuwong S, Aksaranugraha S, Asavatanabodee P, Saengnipanthkul S, The Thai Study Group. The efficacy, safety and carry-over effect of diacerein in the treatment of painful knee osteoarthritis: a randomised, double-blind, NSAID-controlled study. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15(6):605–14.

Sharma A, Rathod R, Baliga VP. An open prospective study on postmarketing evaluation of the efficacy and tolerability of diacerein in osteo-arthritis of the knee (DOK). J Indian Med Assoc. 2008;106(1):54–6, 58.

Brahmachari B, Chatterjee S, Ghosh A. Efficacy and safety of diacerein in early knee osteoarthritis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(10):1193–8.

Singh K, Sharma R, Rai J. Diacerein as adjuvant to diclofenac sodium in osteoarthritis knee. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15(1):69–77.

Rintelen B, Neumann K, Leeb BF. A meta-analysis of controlled clinical studies with diacerein in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1899–906 (Erratum in: Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):444).

Fidelix TS, Soares B, Fernandes Moca Trevisani V. Diacerein for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;1:CD005117.

Fidelix TS, Macedo CR, Maxwell LJ, Fernandes Moca Trevisani V. Diacerein for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD005117.

Bartels EM, Bliddal H, Schondorff PK, Altman RD, Zhang W, Christensen R. Symptomatic efficacy and safety of diacerein in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(3):289–96.

Mattara L. DAR: indagini “controllate” nel trattamento della osteoartosi [DAR “Controlled” studies in treatment of osteoarthrosis]. Paper presented at: Simposio Proter sulla diacereina. 86th Congresso Nazionale della Societa Italiana di Medicina Interna, 1985 Sep 24–27; Sorrento, Italy. Italian.

Pietrogrande V, Leonardi M, Pacchioni C. Risultati della sperimentazione clinica in pazienti artrosici di un nuovo farmaco: la diacereina [Results of a clinical study with a new drug (Diacerein) in osteoarthritis patients]. Paper presented at: Simposio Proter sulla diacereina. 86th Congresso Nazionale della Societa Italiana di Medicina Interna, 1985 Sep 24–27; Sorrento, Italy. Italian.

Fioravanti A, Marcolongo R. Efficacia terapeutica della Diacereina (DAR) nell’artrosi del ginocchio e dell’ anca [Therapeutic effectiveness of Diacerhein (DAR) in arthrosis of knee and hip]. Paper presented at: Toscana Medicina Symposium on Diacereina, Pisa, Italy. 1985 Oct 1. Italian.

Mordini M, Nencioni C, Lavagni A, Camarri E. Diacereina VS naproxene nella coxo-gonoartrosi: studio randomizzato in doppio ciego [Diacerhein versus naproxen in coxo-gonarthrosis: double-blind randomized study]. Paper presented at: 27th Congresso Nazionale della Societa Italiana di Reumatologia, 1986 Oct 30–Nov 2; Montecatini, Italy. Italian.

Mantia S. A controlled study of the efficacy and tolerability of Diacetylrhein in the functional manifestations of osteoarthritis of the hip and the knee. A double-blind study versus diclofenac [study report]. Palermo (Italy): Hospital of Palermo; 1987.

Portioli I. A naproxen-controlled study on the efficacy and tolerability of diacetylrhein in the functional manifestations of osteoarthritis of the knee and hip. A double-blind study versus naproxen [study report]. Reggio Emilia (Italy): Hospital Santa Maria Nuova; 1987.

Tang FL, Wu DH, Lu ZG, Huang F, Zhou YX. The efficacy and safety of diacerein in the treatment of painful knee osteoarthritis. Paper presented at: 11th Asia Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR) Congress, International Convention Center (ICC), 2004 Sep 11–15; Jeju, Korea.

Ascherl R. Longterm treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a six months placebo-controlled clinical trial with diacerhein. Paper presented at: 2nd OARSI International Congress Symposium: Diacerhein and Interleukin 1 inhibition: a new therapeutical approach in osteoarthritis, 1995 Feb 4–5; Nice, France.

Schulitz KP. Clinical investigation of the efficacy and tolerance of Diacetylrhein (DAR) in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee [study report]. Cologne (Germany): Madaus AG; 1994 Oct 27. 468 p. Report No. R-DA139.

Combe B, Dougados M, Goupille P, Cantagrel A, Eliaou JF, Sibilia J, et al. Prognostic factors for radiographic damage in early rheumatoid arthritis: a multiparameter prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(8):1736–43.

EMA. European Medicines Agency, Assessment report for diacerein containing medicinal products. 2014 Aug 28. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Referrals_document/Diacerein/European_Commission_final_decision/WC500173145.pdf. Accessed 2 Jun 2015.

Renan X, Lepage M, Connan D, Carlhant D, Riche C, Verger P, et al. Cas clinique d’une hépatite fatale a la diacerhéine [Case report of fatal hepatitis from diacerein]. Thérapie. 2001;56(2):190–1. French (Comment in: Thérapie. 2001;56:637–638).

Mattei E, Marzoli GA, Oberto G, Brunetti MM. Diacerein effects on the cardiovascular function of the conscious dog following repeated oral administration [study report]. Rome (Italy): RTC Research Toxicology Centre; 2009. 81 p. RTC Study No. 70600.

Middel B, van Sonderen E. Statistical significant change versus relevant or important change in (quasi) experimental design: some conceptual and methodological problems in estimating magnitude of intervention-related change in health services research. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2:e15.

Zhang W, Robertson J, Jones AC, Dieppe PA, Doherty M. The placebo effect and its determinants in osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(12):1716–23 (Comment in: Minerva. 2009;8(9):117).

Ratnaike RN, Jones TE. Mechanisms of drug-induced diarrhoea in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1998;13(3):245–53.

Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, et al. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2005;42(6):1364–72.

Bessone F. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: What is the actual risk of liver damage? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(45):5651–61.

Gulmez SE, Larrey D, Pageaux GP, Lignot S, Lassalle R, Jove J, et al. Transplantation for acute liver failure in patients exposed to NSAIDs or paracetamol (acetaminophen): the multinational case-population SALT study. Drug Saf. 2013;36(2):135–44.

Rahme E, Barkun A, Nedjar H, Gaugris S, Watson D. Hospitalizations for upper and lower GI events associated with traditional NSAIDs and acetaminophen among the elderly in Quebec, Canada. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(4):872–82.

Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration, Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, Abramson S, Arber N, et al. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):769–79 (Comment in: Lancet. 2013; 382(9894): 746–748).

Whelton A. Nephrotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: physiologic foundations and clinical implications. Am J Med. 1999;106(5B):13S–24S.

Schneider V, Levesque LE, Zhang B, Hutchinson T, Brophy JM. Association of selective and conventional nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs with acute renal failure: A population-based, nested case-control analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(9):881–9.

Pazhayattil GS, Shirali AC. Drug-induced impairment of renal function. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:457–68.

Roberts E, Delgado Nunes V, Buckner S, Latchem S, Constanti M, Miller P, et al. Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015.

Svensson CK, Cowen EW, Gaspari AA. Cutaneous drug reactions. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;53:357–79.

Food and Drug Administration (US). FDA issues public health advisory on Vioxx as its manufacturer voluntarily withdraws the product. 2004. http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/news/2004/NEW01122.html. Accessed 9 Jul 2005.

Jüni P, Nartey L, Reichenbach S, Sterchi R, Dieppe PA, Egger M. Risk of cardiovascular events and rofecoxib: cumulative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2004;364(9450):2021–9.

Chan AT, Manson JE, Albert CM, Chae CU, Rexrode KM, Curhan GC, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and the risk of cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2006;113(12):1578–87.

McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: systematic review of population-based controlled observational studies. PLoS Med. 2011;8(9):1–18.

Walker AM. Quantitative studies of the risk of serious hepatic injury in persons using nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(2):201–8.

Kowalski ML, Makowska JS, Blanca M, Bavbek S, Bochenek G, Bousquet J, et al. Hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)—classification, diagnosis and management: review of the EAACI/ENDA and GA2LEN/HANNA. Allergy. 2011;66(7):818–29.

Sanmarkan AD, Sori T, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ. Retrospective analysis of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis over a period of 10 years. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56(1):25–9.

Page J, Henry D. Consumption of NSAIDs and the development of congestive heart failure in elderly patients: an underrecognized public health problem. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):777–84.

Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, Halls H, Emberson JR, Patrono C. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2006;332(7553):1302–8.

Panova E, Jones G. Benefit-risk assessment of diacerein in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Drug Saf. 2015;38:245–52.

Bruyere O, Cooper C, Arden N, Branco J, Brandi ML, Herrero-Beaumont G, et al. Can we identify patients with high risk of osteoarthritis progression who will respond to treatment? A focus on epidemiology and phenotype of osteoarthritis. Drugs Aging. 2015;32(3):179–87.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ contribution

Pr. Reginster organised the meeting. Pr. Bruyère, Pr. Cooper, Dr. Leeb, Pr. Martel-Pelletier and Pr. Pelletier performed the literature review. All authors have taken part in the discussion and meeting and have critically analysed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This meeting was founded by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis, a Belgian not-for-profit organisation.

Conflicts of interest

Pr. Pavelka has received lecture fees from Glynn Brothers Chemicals that are not related to the preparation of this manuscript. Pr. Bruyère has received research grants from IBSA, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Nutraveris, Pfizer, Rottapharm, Servier, SMB, and Theramex, consulting or lecture fees from Bayer, Genevrier, IBSA, Rottapharm, Servier and SMB, as well as reimbursement for attending meetings from IBSA, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Rottapharm, Servier and Theramex. Pr. Cooper has received consulting fees/honoraria from Alliance for Better Bone Health, Amgen, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Takeda and UCB. Pr. Kanis has received reimbursement for travel expenses from the ESCEO. Dr. Leeb has received consulting and lecture fees from IBSA, Pfizer, Servier and TRB Chemedica that are not related to the preparation opig model of osteoarthritis this manuscript. Dr. Maheu has received reimbursement for travel expenses from the ESCEO. Dr. Monfort declared no conflicts of interest. Pr. Martel-Pelletier and Pr. Pelletier are shareholders in Arthrolab Inc, received reimbursement for travel expenses from the ESCEO, as well as grants, consulting and lecture fees from TRB Chemedica. They also served as expert witnesses during the review of diacerein-containing medicines by the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC). Pr. Rizzoli declared no conflicts of interest. Pr. Reginster has received consulting fees or payments as an advisory board member from Servier, Novartis, Negma, Lilly, Wyeth, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Merckle, Nycomed-Takeda, NPS, IBSA-Genevrier, Theramex, UCB, Asahi Kasei and Endocyte, lecture fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Lilly, Rottapharm, IBSA, Genevrier, Novartis, Servier, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Merckle, Teijin, Teva, Analis, Theramex, Nycomed, NovoNordisk, Ebewee Pharma, Zodiac, Danone, Will-Pharma, and Amgen, and grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Rottapharm, Teva, Roche, Amgen, Lilly, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Servier, Pfizer, Theramex, Danone, Organon, Therabel, Boehringer, Chiltern and Galapagos.

Additional information

On behalf of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO).

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0457-7.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pavelka, K., Bruyère, O., Cooper, C. et al. Diacerein: Benefits, Risks and Place in the Management of Osteoarthritis. An Opinion-Based Report from the ESCEO. Drugs Aging 33, 75–85 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-016-0347-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-016-0347-4