Abstract

Topical ruxolitinib 1.5% cream (Opzelura®), a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, is the first treatment to be approved in several countries for use in patients aged ≥ 12 years with non-segmental vitiligo. In the identical phase III TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 trials, significantly more ruxolitinib cream recipients were able to achieve statistically significant and clinically meaningful facial and total body repigmentation, as well as reductions in vitiligo noticeability, compared with vehicle recipients. Efficacy was sustained in longer-term analyses to week 104 of treatment. Ruxolitinib 1.5% cream was generally tolerable in these trials; the most common treatment-related adverse events were acne, pruritus and exfoliation, all at the application site. As with orally administered JAK inhibitors, topical ruxolitinib carries boxed warnings in the USA for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and thrombosis, although the incidences were low with topical application. Thus, topical ruxolitinib 1.5% cream is an effective and generally tolerable treatment option for patients aged ≥ 12 years with non-segmental vitiligo.

Plain Language Summary

Non-segmental vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disease where the skin throughout the body loses its pigmentation, and is usually managed with topical therapies, light therapy or surgery. Topical ruxolitinib 1.5% cream (Opzelura®) is the first treatment approved in several countries for patients aged ≥ 12 years with non-segmental vitiligo. It inhibits Janus kinase (JAK) proteins, reducing the destruction of skin pigment-producing cells. In two clinical trials, significantly more ruxolitinib cream recipients achieved significant and meaningful skin repigmentation compared with patients who received a non-medicated cream; these results were sustained to week 104 of treatment. Ruxolitinib 1.5% cream was generally tolerable; the most common treatment-related adverse events were acne, itchiness and exfoliation, all at the application site. Topical ruxolitinib has special warnings in the USA for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), blood clots, serious infections, death and cancer (associated with the use of oral JAK inhibitors), although incidence rates for these adverse events were low in the clinical trials. Topical ruxolitinib 1.5% cream is an effective and generally tolerable treatment option for patients aged ≥ 12 years with non-segmental vitiligo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Digital Features for this Adis Drug Evaluation can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25309372 |

First treatment to be approved for patients aged ≥ 12 years with non-segmental vitiligo |

Significantly improves facial and total body repigmentation compared with vehicle; efficacy was sustained in longer-term analyses |

Generally tolerable; boxed warnings in the USA for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, MACE and thrombosis (associated with oral JAK inhibitors) |

1 Introduction

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disease that causes depigmentation through epidermal melanocyte cell destruction, leading to white patches of skin [1]. Vitiligo can be classified as segmental (where depigmented lesions only appear on one side of the body), non-segmental (all other forms of vitiligo) or mixed if both types are present [2]. Non-segmental vitiligo can develop later in life than segmental vitiligo, although both subtypes affect patients equally, irrespective of factors that impact skin colour and reaction to sunlight (e.g. ethnicity, Fitzpatrick skin type) [3]. Although often categorized as a cosmetic condition, vitiligo can have significant negative impacts on an individual’s quality of life (QOL), with patients often experiencing stigma and other psychosocial burdens from the disease [3, 4]. Cosmetic camouflage is usually used to improve QOL, particularly for patients with stable, localized vitiligo [3].

Pharmaceutical management of non-segmental vitiligo involves stabilizing active disease, preventing flare-ups and then repigmentation, mainly utilizing topical corticosteroids and/or topical immunomodulators such as calcineurin inhibitors [2]. Systemic treatment with these drug classes may be required in patients with rapidly progressive disease. Concurrent or subsequent treatment options can include phototherapy, surgery, pigment lasers or cryotherapy [2]. Receiving treatment as early as possible is ideal, as repigmentation is largely reliant on the body area(s) affected by vitiligo and the severity of depigmentation [5]. Treatments thus far have largely been limited in terms of efficacy, leading to high relapse rates [5, 6]. Combined with the chronic nature of the disease, there is a need for new treatment options with sustained efficacy. Additionally, almost all treatment options for vitiligo are unapproved and are therefore used ‘off label’ [5].

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are an emerging drug class for the treatment of non-segmental vitiligo [5]. A topical formulation of ruxolitinib (1.5% cream; Opzelura®), a potent and selective JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, is the first drug to be approved in several countries including the USA, the UK and those of the EU, for use in patients aged ≥ 12 years with non-segmental vitiligo [7,8,9]. Ruxolitinib 1.5% cream is also approved in the USA for the short-term and non-continuous chronic treatment of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis in non-immunocompromised patients aged ≥ 12 years whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable (previously reviewed [10]); however, discussion of this indication is beyond the scope of this article [9]. This article summarizes the pharmacological properties of topical ruxolitinib and reviews clinical data relevant to its use in non-segmental vitiligo.

2 Pharmacodynamic Properties of Ruxolitinib Cream 1.5%

The melanocyte cell destruction characteristic of vitiligo is thought to arise from cytotoxic T lymphocytes produced by autoimmune interferon γ (IFNγ) [7]. IFNγ-dependent chemokines (e.g. CXCL10) mediate the recruitment of cytotoxic lymphocytes towards skin lesion(s), causing depigmentation. The recruitment of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) to cytokine receptors leads to modulation of gene expression and other events in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway [7]. JAK1 and JAK2, mediators of cytokine and growth factor signaling involved in the processes of haematopoiesis and immunity, act downstream of IFNγ signaling [7, 9]. By inhibiting JAK1 and JAK2, and thereby the JAK-STAT pathway, ruxolitinib cream reduces the level of chemokines such as CXCL10 and consequently lessens the extent of skin depigmentation [7].

Preclinical data from cellular assays and animal models show ruxolitinib cream was able to inhibit cytokine-induced STAT signaling and reduce tissue inflammation [11]. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration of ruxolitinib was < 100 nM [11]. In vivo, topical application of ruxolitinib 1.5% cream twice daily resulted in minimal systemic exposure and higher concentrations of ruxolitinib in the dermis compared with oral administration [12]. Topical ruxolitinib application was able to almost completely inhibit JAK-STAT signaling in the dermis for an extended length of time, suggesting its efficacy can be optimized while limiting the potentially adverse systemic effects of JAK inhibition [12].

In an open-label, proof-of-concept, phase II trial, topical ruxolitinib 1.5% cream twice daily for 20 weeks in adults with vitiligo (n = 11 evaluable) resulted in significant repigmentation of facial vitiligo [13]. Significant repigmentation of facial vitiligo was also seen in adults with vitiligo who received topical ruxolitinib cream (1.5% twice daily, 1.5% once daily, 0.5% once daily or 0.15% once daily) for 24 weeks in a randomized, double-blind, dose-ranging, multicentre, phase II trial (n = 157 evaluable) [14]. These results were sustained to week 156 of treatment with open-label ruxolitinib cream [15].

3 Pharmacokinetic Properties of Ruxolitinib Cream 1.5%

The pharmacokinetics of topical ruxolitinib were evaluated in patients aged ≥ 12 years with vitiligo (n = 429) who applied ruxolitinib cream (≈ 1.58 mg/cm2) to the same skin areas twice daily for 24 weeks [7, 8]. The mean steady-state trough plasma concentration of ruxolitinib was 56.9 nM, and the projected area under the concentration curve from time zero to 12 h (AUC0–12 h) was 683 h·nM. The estimated AUC for ruxolitinib was ≈ 2-fold higher in patients with kidney failure. The mean topical bioavailability of ruxolitinib was 9.7% [7, 8].

Based on in vitro data, ruxolitinib is 97% bound to plasma proteins (mostly to albumin) [7, 8]. The mean elimination half-life of topical ruxolitinib was ≈ 3 h [7, 8]. Ruxolitinib is mainly metabolized by, and is a substrate for, cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 enzyme; therefore, CYP3A4 inhibitors can increase the systemic concentration of ruxolitinib (leading to an increased risk of adverse reactions) and CYP3A4 inducers can decrease ruxolitinib concentrations [9]. Topical ruxolitinib is not expected to inhibit or induce the main CYP enzymes, nor inhibit P-gp, BCRP or the main OAT transporter systems [9].

Due to the low systemic exposure of ruxolitinib following topical administration, the potential for drug–drug interactions is expected to be low [7, 8]. The coadministration of ruxolitinib cream with other topical agents for vitiligo management has not been assessed [7, 8].

4 Therapeutic Efficacy of Ruxolitinib Cream 1.5%

The efficacy of topical ruxolitinib was evaluated in two identical, multicentre, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, phase III trials (TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2) [16]. Eligible patients were aged ≥ 12 years with a diagnosis of non-segmental vitiligo with depigmentation on ≤ 10% of body surface area (BSA), including ≥ 0.5% BSA on facial areas and ≥ 3% BSA on non-facial areas. Patients must have scored ≥ 0.5 on the facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI50; range 0–3, where a higher score means a larger area of facial depigmentation) and ≥ 3 on the total VASI (T-VASI; range 0–100, where a higher score means a larger area of total body depigmentation). Exclusion criteria included complete leukotrichia in facial lesions, any dermatological disease that would affect study treatment, and previous use of JAK inhibitor therapy, biologic or experimental therapies (within 12 weeks of baseline), phototherapy (within 8 weeks), immunomodulator therapy (within 4 weeks) or topical treatments (within 1 week) for vitiligo [16].

Patients were randomized in a 2:1 manner to receive topical ruxolitinib 1.5% cream or matching vehicle cream applied to depigmented vitiligo lesions twice daily for 24 weeks [16]. Patients were stratified according to geographical region (North America or Europe) and Fitzpatrick skin type (I–II vs III–IV). Patients who completed the 24-week, double-blind period could then progress to the open-label extension period of the trials and receive ruxolitinib 1.5% cream twice daily for a further 28 weeks (Sect. 4.1) [16].

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients with a decrease of ≥ 75% in the F-VASI (F-VASI75 response) from baseline to week 24 [16]. The key secondary endpoints were F-VASI50 response, F-VASI90 response, T-VASI50 response, a Vitiligo Noticeability Scale (VNS) rating of ‘a lot less noticeable’ or ‘no longer noticeable’ (hereafter VNS response) and the percentage change from baseline in facial BSA affected by vitiligo (F-BSA), all evaluated at week 24 [16].

Baseline patient demographics and disease characteristics were generally comparable between the two treatment groups in both trials, and were representative of a patient population requiring topical treatment for vitiligo [16]. The mean age at baseline was 40.2 years in TRuE-V1 and 38.9 years in TRuE-V2, and most patients (80.3% and 85.1%, respectively) were aged 18–64 years. Around half (56.4% and 50.1%) of the patients were female and most (83.6% and 80.2%) were white, from the North American (66.7% and 70.8%) or European (33.3% and 29.2%) geographical regions. The most common Fitzpatrick skin type was type III (40.0% and 39.1% of patients), followed by type II (34.5% and 25.9%). Baseline F-VASI scores were 0.95 and 0.88, baseline T-VASI scores were 6.47 and 6.90, and baseline F-BSA were 1.09% and 0.96%. More than half (58.2% and 63.8%) of the patients had previously received therapy for vitiligo, most commonly topical calcineurin inhibitors (31.2% and 32.4%) [16].

Treatment with topical ruxolitinib for 24 weeks led to significant skin repigmentation compared with vehicle in patients with non-segmental vitiligo [16]. At primary analysis, the F-VASI75 response rate was significantly (p < 0.001) higher in ruxolitinib cream than vehicle recipients, and the likelihood of achieving F-VASI75 was four-fold higher in ruxolitinib cream recipients (Table 1) [16]. A pooled analysis of the two phase III trials showed a significantly (p < 0.0001) higher proportion of ruxolitinib cream (n = 450) than vehicle (n = 224) recipients achieved F-VASI75 at week 24 (30.7% vs 9.9%), irrespective of patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics [17].

Compared with vehicle, significant (p < 0.01) improvements were seen in all key secondary endpoints in patients treated with ruxolitinib cream (Table 1) [16]. In the pooled analysis, significantly (p ≤ 0.0001) higher proportions of ruxolitinib cream than vehicle recipients achieved F-VASI50 (51.6% vs 21.1%), F-VASI90 (15.4% vs 2.2%), T-VASI50 (23.2% vs 8.1%) and VNS response (23.2% vs 5.3%) at week 24 [18].

Patient health-related QOL (HR-QOL) was generally comparable between ruxolitinib cream and vehicle recipients in pooled analyses of TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, with the exception of treatment satisfaction, which was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in ruxolitinib cream than vehicle recipients at week 24 regardless of baseline patient demographics or disease characteristics [19, 20]. The HR-QOL measures assessed that were not significantly different between the two treatment groups included the Dermatology Life Quality Index, Vitiligo-specific QOL, World Health Organization–Five Well-Being Index and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [19, 20].

4.1 Long-Term Efficacy

Patients who initially received ruxolitinib cream in the double-blinded period continued to receive ruxolitinib cream (hereafter ruxolitinib/ruxolitinib recipients) and patients who initially received vehicle were administered ruxolitinib cream in the open-label extension (hereafter vehicle/ruxolitinib recipients) [16].

In the extension period of the phase III trials, the proportions of patients who achieved the primary and key secondary endpoints were numerically higher in ruxolitinib/ruxolitinib than vehicle/ruxolitinib recipients (statistical analyses are not available), with higher rates than at primary analysis (Table 1) [16]. In the pooled population, F-VASI, T-VASI and VNS response rates were mostly improved or remained stable at week 52 compared with week 24 [21,22,23]. In pooled subgroup analyses of week 52 data, F-VASI75 was achieved irrespective of baseline patient demographics or disease characteristics [24]. The efficacy of ruxolitinib cream at week 52 in adolescent patients (aged 12–17 years) was generally consistent with that of adult patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 [25].

In a longer-term analysis of TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 (n = 222), ruxolitinib cream recipients who had not achieved F-VASI90 by week 52 continued to receive ruxolitinib cream for a further 52 weeks [26]. At week 104, the F-VASI75 response rate was 66.1% and the T-VASI50 response rate was 63.8%. Efficacy responses were generally consistent across the subgroups of age (12–17 years, 18–64 years, ≥ 65 years), Fitzpatrick skin type (I–III, IV–VI), F-BSA (< 1.5%, ≥ 1.5%), baseline disease status (stable, progressive) and previous therapy (topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, phototherapy) [26]. In patients who had not achieved F-VASI90 by week 52 of treatment, F-VASI responses remained stable or were improved at week 104 in 64.4% and 19.6% of patients, respectively; T-VASI responses were stable or were improved in 61.3% and 22.2% of patients [27].

5 Tolerability of Ruxolitinib Cream 1.5%

Ruxolitinib 1.5% cream was generally tolerable in patients aged ≥ 12 years with non-segmental vitiligo, as evaluated in the TRuE-V trials [16]. In the double-blind treatment period, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 45.7% of ruxolitinib cream recipients and 38.5% of vehicle recipients in TRuE-V1, and in 50.0% and 33.9% of ruxolitinib cream and vehicle recipients, respectively, in TRuE-V2. These TEAEs were mostly mild or moderate in severity. The most common (incidence ≥ 5% in ruxolitinib cream recipients) TEAEs were application-site acne (5.9% of ruxolitinib cream recipients vs 0% of vehicle recipients in TRuE-V1; 5.7% vs 2.6% in TRuE-V2) and application-site pruritus (5.0% vs 3.7% in TRuE-V1; 5.3% vs 1.7% in TRuE-V2) [16].

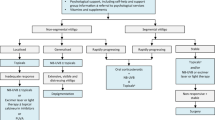

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) occurred in 17.2% and 9.2% of ruxolitinib cream and vehicle recipients in TRuE-V1, respectively, and in 12.3% and 5.2% of patients in TRuE-V2; the most common TRAEs in the two trials are summarized in Fig. 1 [16]. In a pooled analysis of both trials, TRAEs occurred in 14.7% of ruxolitinib cream recipients and 7.6% of vehicle recipients; all were mild-to-moderate in severity [18].

Most common treatment-related adverse events (all of which occurred at the application site) in patients with non-segmental vitiligo in the phase III TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 trials [16]. θ zero incidence

Serious TEAEs occurred in 2.7% of ruxolitinib cream recipients and 0.9% of vehicle recipients in TRuE-V1, and in 0.9% of vehicle recipients only in TRuE-V2; none were considered treatment-related [16]. Adverse events (AEs) led to treatment discontinuation for one ruxolitinib cream recipient in each trial (due to fatigue and application-site rash, respectively), and for one vehicle recipient in TRuE-V1 (due to nausea and headache) [16]. In the pooled analysis, serious TEAEs occurred in 1.8% of ruxolitinib cream recipients and 0.4% of vehicle recipients, and none were considered treatment-related [18]. In subgroup analyses, the tolerability of ruxolitinib cream was comparable regardless of patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics [17].

Tolerability results from the extension periods in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 were generally consistent with the tolerability profile of ruxolitinib cream in the double-blind treatment periods [16]. TRAEs occurred in 3.6% of ruxolitinib/ruxolitinib recipients and 5.6% of vehicle/ruxolitinib recipients in TRuE-V1, and in 6.0% and 6.1% of patients, respectively, in TRuE-V2. These were most commonly application-site acne (0.5% of ruxolitinib/ruxolitinib recipients in TRuE-V1 only; 1.5% vs 3.1% in TRuE-V2, respectively) and application-site pruritus (1.1% of vehicle/ruxolitinib recipients in TRuE-V1 only) [16]. In pooled analyses of the extension periods of TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 (n = 637), TEAEs occurred in 52.1% of patients, which were most commonly COVID-19 (6.1% of patients), application-site acne (5.3%) and nasopharyngitis (4.9%) [28]. Serious TEAEs were reported in 2.2% of patients; none were considered related to topical ruxolitinib treatment [28]. Ruxolitinib cream was well tolerated in adolescents and had a comparable tolerability profile to adults at week 52; TRAEs were reported in 12.9% of adolescents and no serious TRAEs occurred [25].

The tolerability profile of topical ruxolitinib at 104 weeks of treatment was consistent with previous analyses; TRAEs developed in 6.3% of patients, irrespective of demographic subgroup, and were all mild-to-moderate in severity [26].

Ruxolitinib cream is associated with several AEs of special interest (from previous experience in clinical trials utilizing oral ruxolitinib or other oral JAK inhibitors for inflammatory conditions), including serious infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and thrombosis [9]. In the pooled population at week 52, serious infections were reported in 0.5% of ruxolitinib/ruxolitinib recipients, with one case each of appendiceal abscess, appendicitis and hepatitis infectious mononucleosis [28]. Malignancy developed in 0.6% of patients, most commonly basal cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, papillary thyroid cancer and prostate cancer (in one patient each). Thromboembolic events were reported in 0.2% of patients (i.e. transient ischaemic attack in one patient) [28].

In an analysis of post-marketing safety data for ruxolitinib cream from the first year following approval, ruxolitinib 1.5% cream was found to be generally well tolerated [29]. Out of 589 reported events, 44.1% were AEs [most commonly application-site pain (2.7% of events), atopic dermatitis and skin irritation (both 2.5%)], 0.7% were serious AEs (none were associated with oral JAK inhibition) and none were fatal. The association of these AEs with ruxolitinib cream could not be assessed [29].

6 Dosage and Administration of Ruxolitinib Cream 1.5%

Topical ruxolitinib 1.5% cream is approved in several countries, including the USA, the UK and those of the EU, for the treatment of non-segmental vitiligo in patients aged ≥ 12 years [7,8,9]; patients in the EU [7] and UK [8] must also have facial involvement. The approved dosage is a thin layer of cream applied twice daily (minimum 8 h between each application) to depigmented skin areas (avoiding the lips to prevent ingestion), up to a maximum of 10% of BSA (i.e. an area as large as 10 times the palm of one hand with the five fingers) [7,8,9]. Dependent on body region, patients should not use more than one 60 g tube per week [9] or two 100 g tubes per month [7,8,9]. Patients may require treatment for longer than 24 weeks [7,8,9]; however, discontinuing ruxolitinib cream should be considered in the EU and UK if there is < 25% repigmentation in the affected area(s) following 52 weeks of treatment [7, 8].

Due to lack of data, ruxolitinib cream is contraindicated in pregnancy in the EU and UK; patients must use an effective form of contraception during treatment and for 4 weeks after stopping treatment [7, 8]. A recommendation has not been made in the USA regarding use in pregnancy [9]. Patients must avoid breastfeeding during treatment and for ≈ 4 weeks after the last dose of ruxolitinib cream [7,8,9]. Due to lack of safety data, ruxolitinib cream should be avoided in patients with kidney failure [7, 8].

Topical ruxolitinib carries boxed warnings in the USA for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, MACE and thrombosis, which are known to be risks associated with orally administered JAK inhibitors (Sect. 5) [9]. Therefore, the risks and benefits should be considered before starting or continuing topical ruxolitinib treatment, particularly in patients with known or risk factors for malignancy, cardiovascular risk factors or in past or current smokers [9].

Local prescribing information should be consulted for detailed information regarding administration, use in special patient populations, and other warnings and precautions.

7 Current Status of Ruxolitinib Cream 1.5% in the Management of Non-Segmental Vitiligo

Topical ruxolitinib is the first pharmacological treatment to be approved for the treatment of patients aged ≥ 12 years with non-segmental vitiligo, based on results from the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 trials. Ruxolitinib cream has been included as a treatment option in the position statement from the International Vitiligo Task Force on managing vitiligo [2, 5]. The British Association of Dermatologists guideline for the management of people with vitiligo was updated prior to the approval of ruxolitinib cream in non-segmental vitiligo; further updates are awaited with interest [30].

From previous clinical experience in patients with vitiligo, F-VASI75 and T-VASI50 are considered to be the thresholds for clinically meaningful results [16, 31]. In TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, significantly more ruxolitinib cream than vehicle recipients achieved these endpoints at week 24 of treatment (Sect. 4). Efficacy results at week 52 were comparable between the treatment groups, and efficacy was sustained to week 104 of treatment in a long-term extension (Sect. 4). Efficacy was seen irrespective of age, providing a useful addition to the scarce evidence for treatments available for children and adolescents with vitiligo [2]. Ruxolitinib cream was generally tolerable in these trials, as no systemic TRAEs resulted from topical ruxolitinib treatment and there was a low incidence of AEs related to JAK inhibition (Sect. 5). With the exception of treatment satisfaction (which favoured ruxolitinib cream), no statistically significant between-group differences were seen with regards to the HR-QOL outcomes evaluated (Sect. 4). A systematic review and meta-analysis of a phase II trial and the two TRuE-V trials confirmed that ruxolitinib cream was significantly more effective than vehicle in all efficacy measures, and treatment resulted in a comparable incidence of TEAEs to vehicle [32].

A potential limitation in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 was that enrolled patients were mainly white and had Fitzpatrick skin types II–III, which may impact whether the results can be generalized to patients with darker skin types (particularly as vitiligo prevalence rates are generally higher in India and Africa [3]) [16]. Additionally, though significant repigmentation was seen in the TRuE-V trials, there is a substantial likelihood of relapse in patients with non-segmental vitiligo [2]. A lack of multiplicity corrections for TRuE-V data from week 52 onwards means statistical analyses are descriptive only; thus, formal evaluation will be helpful in determining the long-term efficacy of ruxolitinib cream and its capacity as a maintenance treatment [16]. Direct comparison data between ruxolitinib cream and the other widely used therapies, especially the first-line options, will also be useful to fully evaluate its place in the management of non-segmental vitiligo [32].

In conclusion, topical ruxolitinib is an effective and generally tolerable treatment option for patients aged ≥ 12 years with non-segmental vitiligo.

Data Selection Ruxolitinib Cream 1.5%: 114 records identified

Duplicates removed | 2 |

Excluded during initial screening (e.g. press releases; news reports; not relevant drug/indication; reviews; case reports; non-randomized trial) | 21 |

Excluded during writing (e.g. reviews; duplicate data; small patient number; non-randomized and/or phase I trials) | 59 |

Cited efficacy/tolerability articles | 13 |

Cited articles not efficacy/tolerability | 19 |

Search Strategy: EMBASE, MEDLINE and PubMed from 1946 to present. Clinical trial registries/databases and websites were also searched for relevant data. Key words were ruxolitinib, Opzelura, INCB-18424, vitiligo. Records were limited to those in English language. Searches last updated 20 Mar 2024 | |

Change history

29 May 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-024-02055-y

References

Böhm M, Schunter JA, Fritz K, et al. S1 guideline: diagnosis and therapy of vitiligo. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2022;20(3):365–78.

van Geel N, Speeckaert R, Taïeb A, et al. Worldwide expert recommendations for the diagnosis and management of vitiligo: position statement from the International Vitiligo Task Force part 1: towards a new management algorithm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(11):2173–84.

AL-smadi K, Imran M, Leite-Silva VR, et al. Vitiligo: a review of aetiology, pathogenesis, treatment, and psychosocial impact. Cosmetics. 2023;10(3):84.

Bibeau K, Ezzedine K, Harris JE, et al. Mental health and psychosocial quality-of-life burden among patients with vitiligo: findings from the global VALIANT study. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(10):1124–8.

Seneschal J, Speeckaert R, Taïeb A, et al. Worldwide expert recommendations for the diagnosis and management of vitiligo: position statement from the international Vitiligo Task Force part 2: specific treatment recommendations. J Eur Dermatol Venerol. 2023;37(11):2185–95.

Martins C, Migayron L, Drullion C, et al. Vitiligo skin T cells are prone to produce type 1 and type 2 cytokines to induce melanocyte dysfunction and epidermal inflammatory response through Jak signaling. J Investig Dermatol. 2022;142(4):1194-205.e7.

Incyte Biosciences Distribution B.V. Opzelura 15 mg/g cream: EU summary of product characteristics. 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu. Accessed 20 Mar 2024.

Incyte Biosciences UK Ltd. Opzelura 15mg/g cream: UK summary of product characteristics. 2023. https://products.mhra.gov.uk. Accessed 20 Mar 2024.

Incyte Corporation. OPZELURA™ (ruxolitinib) cream, for topical use: US prescribing information. 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Accessed 20 Mar 2024.

Hoy SM. Ruxolitinib cream 1.5%: a review in mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24(1):143–51.

Fridman JS, Scherle PA, Collins R, et al. Preclinical evaluation of local JAK1 and JAK2 inhibition in cutaneous inflammation. J Investig Dermatol. 2011;131(9):1838–44.

Persaud I, Diamond S, Pan R, et al. Plasma pharmacokinetics and distribution of ruxolitinib into skin following oral and topical administration in minipigs. Int J Pharm. 2020;590(119889):1–6.

Rothstein B, Joshipura D, Saraiya A, et al. Treatment of vitiligo with the topical Janus kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(6):1054-60.e1.

Rosmarin D, Pandya AG, Lebwohl M, et al. Ruxolitinib cream for treatment of vitiligo: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10244):110–20.

Harris JE, Pandya AG, Lebwohl M, et al. Safety and efficacy of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo: 156-week data from a phase II study [abstract no. P96 plus poster]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187(Suppl. 1):80–1.

Rosmarin D, Passeron T, Pandya AG, et al. Two phase 3, randomized, controlled trials of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(16):1445–55.

Rosmarin D, Ezzedine K, Desai S. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo by patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics: pooled subgroup analysis from two randomized phase 3 studies [abstract no. 35187 plus poster]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(3):AB50.

Rosmarin D, Ezzedine K, Md P, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo: week 24 pooled analysis of the TRuE-V phase 3 studies [abstract no. 34789 plus poster]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(3):AB51.

Ezzedine K, van Geel N, Butler K, et al. Subgroup analysis of quality of life and treatment satisfaction by disease duration and use of prior treatment: pooled results from two randomized phase 3 studies of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo [abstract no. CO108 plus poster]. Value Health. 2022;25(7 Suppl.):S324.

Pandya AG, van Geel N, Butler K, et al. Subgroup analysis of quality of life and treatment satisfaction by baseline patient characteristics: pooled results from two randomized phase 3 studies of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo [abstract no. CO96 plus poster]. Value Health. 2022;25(7 Suppl.):S321–2.

Harris JE, Rosmarin D, Seneschal J, et al. Facial vitiligo area scoring index response maintenance or shift during 52 weeks of ruxolitinib cream treatment for vitiligo: pooled analysis of the TRuE-V phase 3 studies [abstract no. 43912 plus poster]. In: American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting. 2023.

Rosmarin D, Harris JE, Wolkerstorfer A, et al. Total vitiligo area scoring index response maintenance or shift during 52 weeks of ruxolitinib cream treatment for vitiligo: pooled analysis of the TRuE-V phase 3 studies [abstract no. 43938 plus poster]. In: American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting. 2023.

Ezzedine K, Passeron T, Rosmarin D, et al. Vitiligo noticeability scale score maintenance or shift during 52 weeks of ruxolitinib cream treatment for vitiligo: pooled analysis of the TRuE-V phase 3 studies [abstract no. 43959 plus poster]. In: American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting. 2023.

Seneschal J, Wolkerstorfer A, Desai SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo by patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics: week 52 pooled subgroup analysis from two randomized phase 3 studies [abstract no. 555 plus poster P1383]. In: 31st European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Congress. 2022.

Seneschal J, Grimes P, Desai SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream in adolescent patients with vitiligo: pooled analysis of the 52-week TRuE-V phase 3 studies. In: Society for Pediatric Dermatology 47th Annual Meeting. 2022.

Seneschal J, Wolkerstorfer A, Ezzedine K, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream through week 104 in patients with vitiligo: subgroup analysis of the TRuE-V long-term extension phase 3 study [abstract no. 927 plus poster P2229]. In: 32nd European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Congress. 2023.

Rosmarin D, Sebastian M, Amster M, et al. Facial and total vitiligo area scoring index response shift during 104 weeks of ruxolitinib cream treatment for vitiligo: results from the open-label arm of the TRuEV long-term extension phase 3 study [abstract plus presentation]. In: American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting. 2023.

Pandya AG, Ezzedine K, Rosmarin D, et al. Treatment-emergent adverse events of interest for janus kinase inhibitors: pooled analysis of the 52-week TRuE-V phase 3 studies of ruxolitinib cream treatment for vitiligo [abstract no. 43978 plus poster]. In: American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting. 2023.

Hu W, Thornton M, Livingston RA. Real-world use of ruxolitinib cream: safety analysis at 1 year. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25(2):327–32.

Eleftheriadou V, Atkar R, Batchelor J, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of people with vitiligo 2021. Br J Dermatol. 2021;186(1):18–29.

Kitchen H, Wyrwich KW, Carmichael C, et al. Meaningful changes in what matters to individuals with vitiligo: content validity and meaningful change thresholds of the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI). Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(7):1623–37.

Ehsan M, Rehman AU, Ayyan M, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;31(1):350–3.

Acknowledgements

During the peer review process, the manufacturer of ruxolitinib cream was also offered an opportunity to review this article. Changes resulting from comments received were made on the basis of scientific and editorial merit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The preparation of this review was not supported by any external funding.

Authorship and Conflict of interest

Connie Kang is a salaried employee of Adis International Ltd/Springer Nature, and declares no relevant conflicts of interest. All authors contributed to this article and are responsible for its content.

Ethics approval, Consent to participate, Consent to publish, Availability of data and material, Code availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

The manuscript was reviewed by: D. Ioannidis, 1st Department of Dermatology, Aristotle University School of Medicine, Thessaloniki, Greece; M.Y. Wang, Department of Dermatology, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China.

The original online version of this article was revised due to retrospective open access request.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, C. Ruxolitinib Cream 1.5%: A Review in Non-Segmental Vitiligo. Drugs 84, 579–586 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-024-02027-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-024-02027-2