Abstract

Poor adherence to statins increases cardiovascular disease risk. We systematically identified 32 controlled studies that assessed patient-centered interventions designed to improve statin adherence. The limited number of studies and variation in study characteristics precluded strict quality criteria or meta-analysis. Cognitive education or behavioural counselling delivered face-to-face multiple times consistently improved statin adherence compared with control groups (7/8 and 3/3 studies, respectively). None of four studies using medication reminders and/or adherence feedback alone reported significantly improved statin adherence. Single interventions that improved statin adherence but were not conducted face-to-face included cognitive education in the form of genetic test results (two studies) and cognitive education via a website (one study). Similar mean adherence measures were reported for 17 intervention arms and were thus compared in a sub-analysis: 8 showed significantly improved statin adherence, but effect sizes were modest (+7 to +22 % points). In three of these studies, statin adherence improved despite already being high in the control group (82–89 vs. 57–69 % in the other studies). These three studies were the only studies in this sub-analysis to include cognitive education delivered face-to-face multiple times (plus other interventions). In summary, the most consistently effective interventions for improving adherence to statins have modest effects and are resource-intensive. Research is needed to determine whether modern communications, particularly mobile health platforms (recently shown to improve medication adherence in other chronic diseases), can replicate or even enhance the successful elements of these interventions while using less time and fewer resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

We narratively reviewed 32 systematically identified, controlled studies that assessed interventions designed to improve adherence to statins. |

Absolute increases in mean adherence to statins were modest (+7 to +22 %) for successful interventions that used comparable adherence measures (medication possession ratio, proportion of days covered, or similar). Nevertheless, increased adherence to statins generally also improved cholesterol measures. |

Cognitive education delivered face-to-face multiple times was the most consistent feature of successful interventions, although successful examples of other intervention types (e.g. behavioural counselling), were also found. |

Most interventions that improve adherence to statins are resource intensive, despite only having modest effects. Mobile health platforms may be a more efficient alternative, but have not been well explored in relation to statin use. |

1 Introduction

Hypercholesterolemia is one of the main modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1, 2]. There is compelling evidence that statins are effective at reducing lipid levels, the risk of CVD events and mortality [3, 4]. Concordantly, poor adherence to statins has been shown to increase the risk of CVD morbidity and death [5–7]. Nonadherence to statins has been estimated to be about 50 % over 5 years, with the highest rates of discontinuation observed during the first year of treatment [8–10]. Poor adherence to medication is the result of complex interactions between patient- physician- and healthcare-related factors [11]. Patient-reported reasons for reduced adherence to statins include insufficient knowledge of their benefits (e.g. the belief that statins are unnecessary for good health) uncertainty over whether treatment should be continued because of a lack of follow-up by clinicians, distrust of clinicians’ instructions, concerns about the short- and long-term risks of taking statins, preferences for alternative treatment such as herbal remedies, and the inconvenience of taking lipid-lowering medications [e.g. requirement for laboratory testing, complicated dosing regimens—especially when patients are taking many different (not necessarily all CVD-related) medications] [11–14]. Age (usually <50 years and ≥70 years), female sex, lower income and use in primary prevention (relative to secondary prevention) are also associated with nonadherence to statins [15]. Interventions to enhance adherence to statins are warranted to improve health outcomes and decrease medical costs. A number of high-quality reviews have attempted to assess the impact of interventions on adherence to medication in general [16–18], but none (to our knowledge) have focused specifically on statins. The main objectives of this narrative review were therefore to undertake a systematic search for studies assessing the impact of patient-centered interventions on adherence to statins, systematically categorize interventions according to their component parts, and then attempt to determine which intervention components are the most effective.

2 Methods

2.1 Systematic Searches

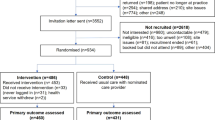

Systematic searches were conducted in PubMed and Embase for the period from January 2000 to January 2015 (see Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram). Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms (PubMed) and ‘explosion’ terms (Embase) were used when available. Intervention-related search terms were difficult to define comprehensively, and were not covered by standard MeSH terms. The search string was therefore kept broad by including only terms describing statins and adherence. Studies describing patient-centered interventions were then identified manually at the post-search stage by screening titles/abstracts and/or full papers. The systematic searches were performed and screened by one author (SP) and then independently reviewed by a second author (MM-B).

2.2 Study Inclusion Criteria

To be included, studies had to have a control arm and a post-intervention study period of at least 3 months. Prospective studies that were not randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and retrospective studies were included provided that controls were matched to the intervention group or, if unmatched controls were used, potential differences in patient characteristics between the intervention and control group (i.e. confounding) were adjusted for in the statistical analysis. Studies assessing the impact of interventions on measures of persistence (defined as the length of time between treatment initiation and the last dose [19]) that did not also include measures of implementation (defined as the extent to which patients' actual dosing corresponds to the prescribed dosing regimen [19]) were not considered to measure adherence to statins for the purposes of this study and were therefore excluded. No other study quality criteria were applied.

2.3 Classification of Interventions

There is no accepted system for classifying interventions that target adherence to statins. We therefore adapted an approach used in a recent systematic review of interventions designed to enhance adherence to medication [16]. Components of each intervention were classified into 1 of 5 main categories: cognitive education, behavioural counselling, medication reminder systems, adherence feedback and treatment simplification (see Box 1 in Appendix for detailed descriptions). Information on how interventions were delivered (face-to-face, telephone, mail, etc.), and whether they were delivered once or multiple times was also collected systematically. Categorization of interventions using this system was performed by two authors (MM-B and SP) and was then independently reviewed (and modified if necessary) by the remaining authors (MJK, MA and SB). When more than one intervention component was used in a study they were all captured as part of the intervention classification. In this way, interventions of varying complexity were represented. As with any review, our analysis is limited by what was reported in each study. We therefore cannot exclude the possibility that other intervention components were used in some studies but not reported.

2.4 Analysis of Data on Adherence to Statins

Owing to considerable variation in study designs and the small number of studies using just one type of intervention, a meta-analysis of the data was not deemed appropriate. We therefore performed a narrative synthesis of the available data, consisting of two approaches. The first was a broad attempt to identify potential commonalities/differences in terms of interventions that significantly improve adherence to statins. This analysis (represented in Fig. 2) included all of the identified studies regardless of the adherence measure used. The second, more stringent analysis included only studies that used objective measures of adherence to statins such as prescription refills, pill counts or electronic monitoring systems and reported absolute differences in mean statin adherence levels [medication possession ratio (MPR), proportion of days covered (PDC) or similar]. This analysis (represented in Fig. 3) allowed the magnitude of the effects of different interventions on adherence to statins to be compared, albeit across fewer studies. The absolute mean difference in adherence to statins between an intervention and a control group was considered to be more transparent and clinically meaningful than differences in the proportion of adherent patients, which tend to be based on fairly arbitrary definitions of what constitutes adherence (e.g. MPR ≥ 0.80), and can underestimate or overestimate the impact of an intervention depending on how close patients already are to meeting the definition of adherence being used. For example, if most patients in a population have a mean MPR of 0.75 (i.e. currently taking 75 % of their doses), an intervention causing an absolute increase in mean adherence to medication of 6 % might shift a high proportion of patients from being defined as non-adherent to being defined as adherent, despite the questionable clinical significance of such a small effect.

Combinations of components used in intervention groups (n = 34) to try to improve adherence to statins. Each column represents one intervention group. Intervention groups are ranked by the number of components involved. Components in each intervention group are illustrated by blue boxes (those in yellow boxes were applied to both the intervention group and the control group). Pink boxes highlight components that were not applied to all patients in the intervention group. Columns with interventions associated with a significant improvement in at least one measure of adherence are highlighted in green. Letters in boxes denote whether the component was used a single time (S) or multiple times (M). Symbols indicate who delivered the intervention: *physician; †pharmacist; and ‡nurse. Roman numerals indicate the number of ‘other’ intervention components used. The full text of the descriptions of the interventions used in each study in relation to how they were categorized is provided in Supplementary Table 1 (online)

Studies reporting the mean proportion of days covered, medication possession ratio or similar parameter by intervention type. 1 Cognitive education, 2 behavioural counselling, 3 treatment simplification, 4 medication reminders, 5 adherence feedback, A face-to-face, B telephone (person), C hard copy materials, D telephone (automated), E other delivery components (Roman numerals indicate number of other delivery components), S single time, M multiple times. *Statistically significant difference between control and intervention groups (p < 0.05)

3 Results

3.1 Searches

Of 3613 combined search ‘hits’, 32 studies were identified that fulfilled the inclusion criteria [20–51]. The main reasons for exclusion were: irrelevant study topic, intervention directed towards healthcare professionals (rather than being patient-centered), intervention not sufficiently described and insufficient data on adherence to statins.

3.2 Study Characteristics

Most (20/32) of the included studies were conducted in North America [21–24, 26–30, 32, 36, 37, 43, 45–51], with 9 conducted in Europe [20, 31, 34, 35, 38, 39, 41, 42, 44] and 3 in Asia [25, 33, 40]. The median sample size for the intervention group was 202 (range: 15–29,042) and the median study duration was 12.0 months (range: 3 months–2 years). Many studies did not specify the reason for statin use in the included patients [23, 24, 26, 27, 29–31, 38, 41–43, 47, 49, 50]. Of those that did, half indicated that statins were prescribed for secondary CVD prevention [20–22, 25, 33, 44–46, 48]. Other indications included primary hypercholesterolemia [35], diabetes [28, 32] and elevated CVD risk [36, 37, 39, 51]. Five studies selected patients based on poor adherence to statin therapy [24, 26, 31, 36, 38]. Two studies [31, 32] contained 2 intervention arms; hence, data from 34 intervention arms were included in the overall analysis. Study designs, patient characteristics, intervention types (based on the categorization used in Fig. 2) and the methods and raw data for all statin adherence (implementation and persistence) and cholesterol measures used in each study are summarized in Table 1. The full published descriptions of the interventions used in each study and how they were categorized for inclusion in this review are provided in Supplementary Table 1 (online).

3.3 Interventions and Statin Adherence (Implementation)

The first parts of this section of the narrative synthesis (Sects. 3.3.1–3.3.4) draw on data in Fig. 2, which presents all identified studies in order (from left to right) of the increasing number of intervention components they contained. In several of these studies the outcome measure for adherence to statins was not defined [25, 33, 39], was described only as self-reported [24, 37], or used patient-reported questionnaires to estimate adherence to statins [29, 34], increasing the risk of bias in their reported results. Section 3.3.5 draws on data in Fig. 3, which presents studies in the same order as Fig. 2 but is limited to those using more reliable outcome measures of adherence to statins, and includes a quantitative component (absolute differences in mean statin adherence levels based on MPR, PDC or similar between intervention and control). Nevertheless, trends in either analysis may still be biased by substantial variation in other study characteristics (Table 1), or be due to chance alone owing to the small number of available studies. While we have done our best to only report robust trends that (in the collective opinion of the authors) are unlikely to be artefactual, the reader should factor the above limitations into their interpretation of the results.

3.3.1 Cognitive Education Interventions

Cognitive education was the most frequently included intervention (Fig. 2). Only 3 studies (all RCTs) of 13 that used cognitive education as the only type of intervention did not report significantly improved adherence to statins compared with controls (Fig. 2; Table 1) [22, 41, 51]. Most (8/10) of the studies that did report significantly improved adherence to statins with cognitive education only were RCTs or used a similarly unbiased prospective study design (randomization at hospital rather than patient level, intervention assigned based on appointment times, or patients used as own controls) (Table 1) [20, 21, 25, 33, 34, 36, 37, 40]. The other two studies were prospective but not randomized: one used a matched control group, while the other used an un-matched control group but adjusted the statistical analysis for confounders (Table 1) [23, 24].

There were seven RCTs (or similar) and one prospective study that included multiple, face-to-face, cognitive education sessions in their interventions (Table 1) [33–35, 38, 40–42, 48]. All of these, except for Eussen et al [41], reported a statistically significant improvement in adherence to statins (Fig. 2). Conversely, Eussen et al was the only one of 14 studies that did not report a statistically significant improvement in adherence to statins that included multiple, face-to-face, cognitive education sessions (Fig. 2). Importantly, Eussen et al reported very high mean adherence to statins (MPR of 99 %) in the control group (Fig. 3) [41], which would make it impossible to resolve an effect on adherence to statins even if one existed for this intervention.

There were nine studies that included a single, face-to-face, cognitive education session in their intervention, of which eight were RCTs or similar and one was a prospective study that included matched controls (Table 1) [20, 21, 31, 36, 37, 43, 45, 46, 51]. Of the five studies that reported a statistically significant improvement in adherence to statins, all except Yilmaz et al [20] also included cognitive-education delivered multiple times via other methods (telephone, hard-copy materials or both), compared with none of the four studies that did not show improved adherence to statins (Fig. 2).

There were three studies that achieved a significant improvement in adherence to statins despite including only a single cognitive education session that was not delivered face-to-face (Fig. 2). Two of these studies (both prospective but not randomized) were unique in providing patients with test results for genetic polymorphisms as the sole intervention: one genetic variant was associated with an increased risk of myopathy with statin use and premature discontinuation (SLCO1B1*5 gene variant; genotyping information provided via a website) [24] and the other variant had the potential to modulate reductions in coronary heart disease risk in statin users (KIF6 gene variant; genotyping information provided in hard copy form along with genotype-guided treatment recommendations) [23]. In one of these studies, adherence to statins was defined as self-reported, while the other reported adherence to statins as the mean PDC [23, 24]. The third study, by Peng and colleagues, did not define the outcome measure used to assess adherence to statins and employed a clustered (by hospital) randomized study design in which cognitive education materials were provided to the intervention group via a password-protected website [25].

3.3.2 Behavioural Counselling

All three studies that used multiple, face-to-face behavioural counselling sessions significantly improved adherence to statins (mean MPR or PDC) relative to the control group (Fig. 2) [26, 27, 35]. Behavioural counselling consisted of motivational interviews in two of these studies (one retrospective and one where patients were their own controls) and was used alone [26, 27]. In the third study, an RCT, behavioural counselling consisted of patients being asked to adopt a new routine to remind them to take their medication, but was combined with multiple, face-to-face cognitive education sessions [35]. Further patterns regarding the impact of behavioural counselling on adherence to statins were difficult to discern from the data in Fig. 2.

3.3.3 Treatment Simplification

Two studies included treatment simplification in their intervention, both of which reported a significant increase in adherence to statins (Fig. 2). One of these studies was an RCT that combined treatment simplification with multiple cognitive education sessions (face-to-face and via automated calls), a single behavioural counselling intervention (pillbox) and medication reminders [48]. The other study, by Holdford et al, was a non-randomized prospective study that we classified as using treatment simplification plus an optional behavioural counselling component (pill box) [50]. The appointment based medication synchronization (ABMS) intervention program described in the Holdford et al study also included the optional use of ‘medication therapy management’. We could not confidently define this component for inclusion in our classification system, but it should be noted that descriptions of ABMS reported elsewhere indicate it may involve multiple face-to-face behavioural counselling and/or cognitive education sessions [52]. Thus, ABMS may be a more complex intervention than we are able to report here based on our classification of the Holdford et al study.

3.3.4 Medication Reminders and Adherence Feedback

There were eight interventions across five RCTs and one retrospective study that were based on medication reminders and/or adherence feedback (Table 1) [30–32, 39, 42, 48]. All except one of these studies used the MPR, PDC or similar for their outcome measure of adherence to statins. None of the study arms that used only medication reminders and/or adherence feedback reported a significant impact on adherence to statins (Fig. 2). The only two studies using these intervention components that reported significantly increased mean adherence to statins combined them with multiple, face-to-face cognitive education sessions (Fig. 2).

3.3.5 Comparative Effect Sizes for Different Interventions

There were 17 intervention arms across 10 RCTs (or similar), 4 prospective studies and 2 retrospective studies that reported data on adherence to statins using similar, clinically meaningful measures (e.g. mean MPC or PDC) (Table 1) [22, 23, 26–28, 30, 32, 35, 41–45, 48–50]. Significantly increased mean adherence to statins relative to the control group was achieved in three of the seven studies that used only one intervention type: two used multiple, face-to-face motivational interviews [+5 and +7 % points (both behavioural counselling)] [26, 27] and one provided genotyping information for the KIF6 gene variant [+9 % points (cognitive education)] [23] (Fig. 3). These effect sizes are within the range observed in the five studies that combined more than one intervention type and achieved significantly improved adherence to statins (+7 to +22 % points) (Fig. 3) [35, 42, 43, 48, 50]. It is worth noting that the significant improvement in adherence to statins in three of the latter studies occurred despite having much higher mean adherence to statins in the control groups (range: 82–89 %) [35, 42, 48] compared with the three studies that significantly improved adherence to statins using a single intervention type (range: 57–68 %) [23, 26, 27] (Fig. 3). These were also the only studies (other than Eussen et al [41]) in this sub-analysis to incorporate multiple, face-to-face cognitive education sessions into their intervention.

3.4 Interventions and Statin Adherence (Persistence)

Adherence to statins was measured in terms of persistence as well as implementation in nine RCTs, five prospective studies and one retrospective study (Table 1) [20, 22–24, 27, 31, 35, 38, 41–44, 47, 49, 50]. Of 10 studies that measured both of these parameters and reported significantly improved statin implementation compared with controls only Kardas et al did not also report significantly improved persistence (Table 1) [35]. Conversely, of five studies that reported no significant effect of the intervention on statin implementation, only Eussen et al reported any significant effect on persistence [41].

3.5 Impact of Improved adherence to Statins on Cholesterol Measures

The impact of interventions on cholesterol measures (mean LDL–C, LDL–C change from baseline, proportion reaching target LDL–C levels) was reported in addition to their impact on adherence to statins in nine RCTs (or similar) and two prospective studies (Table 1) [20, 21, 24, 32, 34, 36, 39, 40, 45, 48, 51]. Of the seven studies reporting improved adherence to statins with their intervention, five also reported a significant improvement in at least one cholesterol measure (Table 1). All four studies reporting no significant improvement in adherence to statins also reported no significant improvement in any cholesterol measure.

4 Discussion

There is growing interest in establishing which interventions can improve adherence to statins, as evidenced by the fact that most [22/32 (69 %)] of the studies we identified were published in 2010 or later (the search string was designed to capture any articles published since 2000). A number of high-quality reviews have attempted to assess the impact of interventions on adherence to medication [16–18]. However, to our knowledge, we are the first to undertake a systematic search for and analysis of studies addressing this problem in relation to statin use.

We categorized interventions according to their component parts, who delivered them and how they were delivered, in an attempt to identify those that genuinely improve adherence to statins. The main limitation of this approach (others are discussed below) is that most interventions assessed in the literature include more than one type of component, making it difficult to know what contribution individual components are adding to observed improvements in adherence to statins. For this reason, and because of considerable variation in study designs, meta-analysis was not deemed appropriate. Despite these limitations, some interesting trends were observed in our narrative synthesis of the data, from which we believe some cautious inferences can be drawn.

Our findings suggest that face-to-face cognitive education interventions are effective at improving patient adherence, particularly if delivered more than once. Notable exceptions to this were two studies that provided patients with the results of pharmacogenetic tests that were potentially relevant to the efficacy or adverse effects of their statin treatment [23, 24]. These results were delivered only once by mail or via a website and yet significantly improved adherence to statins. It is possible that the benefit of this form of educational material lies in its highly personalized nature, directly linking the treatment to the individual and thus providing motivation for patients to modify medication adherence behaviours.

Although only a few studies were available that used medication reminders or adherence feedback, the data were consistent in showing that these intervention components did not have a significant impact on adherence to statins. The only study that used these interventions and significantly improved adherence to statins also used a face-to-face cognitive education component delivered multiple times, which was the most consistently successful intervention type identified in this review and could therefore be responsible for the observed improvement in adherence to statins in this study [42].

It was also noted that studies using multiple intervention types improved adherence to statins despite mean adherence levels that were generally higher in their control groups than in the control groups of studies that only used one type of intervention. It may be that combining different intervention types is a more effective strategy for improving adherence to statins in populations that already have a relatively high level of statin adherence, although the use of multiple, face-to-face, cognitive education sessions was also a common feature of these studies and could thus have constituted the main ‘active’ component.

Measuring medication adherence accurately is extremely difficult with currently available methods. Several approaches were used in the studies we identified, most of which were indirect and thus questionable in terms of their reliability. The most common method involved monitoring prescription refills, but this merely measures medication possession, not consumption. Indeed, many patients may feel obliged to refill their prescriptions according to their doctor’s instructions, regardless of whether they take the medication. More direct methods of assessing adherence to medication, such as medication event monitoring systems (MEMS), which electronically monitor when medication bottles are opened, and biomarker detection systems, which directly assess medication consumption (e.g. by measuring drug metabolites in urine or plasma), may be better options. However, MEMS is very costly (used in only one of our identified studies [42]), and assessment of biomarkers of adherence to medication may impose a substantial burden on the patient. It is possible, however, that these issues may be overcome in the future. For example, refinement of MEMS technology and its incorporation into the ‘Internet of things’ may enhance affordability, while novel sensor technology and wearables have the potential to increase the practicality of biomarker detection.

Another significant challenge when quantifying the impact of different interventions on adherence to medication is the lack of standardization in terms of how it is compared. In our first analysis we looked for broad, over-reaching patterns in the data that held across different studies in spite of variation in how adherence was measured, or other differences in study characteristics such as study design and patient characteristics. In our second analysis, we compared only studies that assessed the absolute change in adherence to statins (based on MPR, PDC or similar), rather than the proportion of patients shifted towards ‘adherent behaviour’ by interventions. We made this choice because measuring adherent behaviour means that arbitrary thresholds must be defined and this may give an inaccurate impression of the impact of an intervention. Indeed, several studies included in this review reported both absolute change in adherence to statins and the changes in the proportion of patients defined as being adherent to statins, with the latter giving values approximately twice that of the absolute change. The medical relevance of any medication adherence measure can of course be debated, but to help to quantify and compare different interventions, we recommend absolute difference in adherence to medication as the most transparent and easily interpretable measure.

The exact content of the interventions used in several of the included studies could not be easily quantified or categorized, often because it is not practical to publish full details of the materials used to deliver interventions, especially for cognitive education and behavioural counselling approaches (e.g. interview guides, educational pamphlets, videos). Thus, differences between studies that impact on the relative success of their interventions have almost certainly been missed by our broad (though necessarily practical) method of categorization. Furthermore, distinguishing between cognitive education and behavioural counselling approaches can often be conceptually difficult and is prone to subjective interpretation. Nevertheless, any such misclassification would not be likely to be systematically biased in any particular direction and therefore would be unlikely to influence the broad and tentative conclusions of this review.

To our knowledge, none of the interventions identified in this review have been broadly implemented in general healthcare practices. This is most likely to be due to the poor cost effectiveness associated with the most effective interventions, namely cognitive education (and potentially behavioural counselling) delivered via multiple, face-to-face sessions. These approaches are extremely resource intensive (for both patients and providers), requiring substantial time, planning and travel, and appear to have only modest effects. Indeed, the cost of the intervention in the study by Ho and colleagues (the only study providing such data) was estimated at US$360 per patient-year, but yielded a mean increase in the proportion of days covered by statins of only 11 percentage points [48]. The challenge is therefore to find alternatives that can offer similar or enhanced benefits compared with face-to-face consultations but that can be maintained on a long-term basis across the population at an affordable cost. One such alternative could be the use of mobile health (mHealth), which uses smart phone or tablet applications and thus has the potential to reach many patients at a relatively low cost. Compared with other approaches, mHealth has the potential for greater personalization, which appears to be a key factor in effective interventions. A recent review by Hamine et al found that adherence to medication was improved in 56 % of RCTs that used mHealth approaches in patients with chronic diseases [53].

5 Conclusion

In this narrative synthesis of 32 systematically identified studies we found consistent evidence that cognitive education (and possibly also behavioural counselling) delivered face-to-face multiple times improves adherence to statins. Although absolute increases in mean adherence to statins were fairly modest for these interventions (+7 to +22 %), they did tend to be associated with improvements in cholesterol measures. However, these types of interventions are extremely resource intensive and thus are often too costly to apply to the general population. Modern communication and sensor technology in the form of mHealth have recently been used to improve adherence to other chronic disease medications. The lack of studies using these applications to improve adherence to statins suggests that this promising approach has not yet been properly investigated in this therapy area. Given the successful application of mHealth elsewhere, there is reason to be optimistic that the challenge of improving general adherence to statins can be met. Research in this area should be a priority.

References

World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2002. Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. 2002. http://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/. Accessed 5 May 2016.

World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases. 2010. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report2010/en/. Accessed 5 May 2016.

Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, Bhala N, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670–81.

Mills EJ, Wu P, Chong G, Ghement I, Singh S, Akl EA, et al. Efficacy and safety of statin treatment for cardiovascular disease: a network meta-analysis of 170,255 patients from 76 randomized trials. QJM. 2011;104(2):109–24.

Perreault S, Dragomir A, Blais L, Berard A, Lalonde L, White M, et al. Impact of better adherence to statin agents in the primary prevention of coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(10):1013–24.

Perreault S, Ellia L, Dragomir A, Cote R, Blais L, Berard A, et al. Effect of statin adherence on cerebrovascular disease in primary prevention. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):647–55.

Poluzzi E, Piccinni C, Carta P, Puccini A, Lanzoni M, Motola D, et al. Cardiovascular events in statin recipients: impact of adherence to treatment in a 3-year record linkage study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(4):407–14.

Avorn J, Monette J, Lacour A, Bohn RL, Monane M, Mogun H, et al. Persistence of use of lipid-lowering medications: a cross-national study. JAMA. 1998;279(18):1458–62.

Helin-Salmivaara A, Lavikainen PT, Korhonen MJ, Halava H, Martikainen JE, Saastamoinen LK, et al. Pattern of statin use among 10 cohorts of new users from 1995 to 2004: a register-based nationwide study. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(2):116–22.

Jackevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV. Adherence with statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2002;288(4):462–7.

Casula M, Tragni E, Catapano AL. Adherence to lipid-lowering treatment: the patient perspective. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:805–14.

Fung V, Sinclair F, Wang H, Dailey D, Hsu J, Shaber R. Patients’ perspectives on nonadherence to statin therapy: a focus-group study. Perm J. 2010;14(1):4–10.

Harrison TN, Derose SF, Cheetham TC, Chiu V, Vansomphone SS, Green K, et al. Primary nonadherence to statin therapy: patients’ perceptions. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(4):e133–9.

McGinnis B, Olson KL, Magid D, Bayliss E, Korner EJ, Brand DW, et al. Factors related to adherence to statin therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(11):1805–11.

Mann DM, Woodward M, Muntner P, Falzon L, Kronish I. Predictors of nonadherence to statins: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(9):1410–21.

Demonceau J, Ruppar T, Kristanto P, Hughes DA, Fargher E, Kardas P, et al. Identification and assessment of adherence-enhancing interventions in studies assessing medication adherence through electronically compiled drug dosing histories: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Drugs. 2013;73(6):545–62.

Kuntz JL, Safford MM, Singh JA, Phansalkar S, Slight SP, Her QL, et al. Patient-centered interventions to improve medication management and adherence: a qualitative review of research findings. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(3):310–26.

Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, Hobson N, Jeffery R, Keepanasseril A, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD000011.

Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(5):691–705.

Yilmaz MB, Pinar M, Naharci I, Demirkan B, Baysan O, Yokusoglu M, et al. Being well-informed about statin is associated with continuous adherence and reaching targets. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19(6):437–40.

Faulkner MA, Wadibia EC, Lucas BD, Hilleman DE. Impact of pharmacy counseling on compliance and effectiveness of combination lipid-lowering therapy in patients undergoing coronary artery revascularization: a randomized, controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20(4):410–6.

Alsabbagh MW, Lemstra M, Eurich D, Wilson TW, Robertson P, Blackburn DF. Pharmacist intervention in cardiac rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2012;32(6):394–9.

Charland SL, Agatep BC, Herrera V, Schrader B, Frueh FW, Ryvkin M, et al. Providing patients with pharmacogenetic test results affects adherence to statin therapy: results of the Additional KIF6 Risk Offers Better Adherence to Statins (AKROBATS) trial. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014;14(3):272–80.

Li JH, Joy SV, Haga SB, Orlando LA, Kraus WE, Ginsburg GS, et al. Genetically guided statin therapy on statin perceptions, adherence, and cholesterol lowering: a pilot implementation study in primary care patients. J Pers Med. 2014;4(2):147–62.

Peng B, Ni J, Anderson CS, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Pu C, et al. Implementation of a structured guideline-based program for the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke in China. Stroke. 2014;45(2):515–9.

Pringle JL, Boyer A, Conklin MH, McCullough JW, Aldridge A. The Pennsylvania Project: pharmacist intervention improved medication adherence and reduced health care costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(8):1444–52.

Taitel M, Jiang J, Rudkin K, Ewing S, Duncan I. The impact of pharmacist face-to-face counseling to improve medication adherence among patients initiating statin therapy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:323–9.

Thiebaud P, Demand M, Wolf SA, Alipuria LL, Ye Q, Gutierrez PR. Impact of disease management on utilization and adherence with drugs and tests the case of diabetes treatment in the Florida: a Healthy State (FAHS) program. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(9):1717–22.

Johnson SS, Driskell MM, Johnson JL, Dyment SJ, Prochaska JO, Prochaska JM, et al. Transtheoretical model intervention for adherence to lipid-lowering drugs. Dis Manag. 2006;9(2):102–14.

Foreman KF, Stockl KM, Le LB, Fisk E, Shah SM, Lew HC, et al. Impact of a text messaging pilot program on patient medication adherence. Clin Ther. 2012;34(5):1084–91.

Kooy MJ, Van Wijk BLG, Heerdink ER, De Boer A, Bouvy ML. Does the use of an electronic reminder device with or without counseling improve adherence to lipid-lowering treatment? The results of a randomized controlled trial. Front Pharmacol. 2013. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00069.

Pladevall M, Divine G, Wells KE, Resnicow K, Williams LK. A randomized controlled trial to provide adherence information and motivational interviewing to improve diabetes and lipid control. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41(1):136–46.

Wu JH, Sun CL, Zhang SM, Ren XH, Yang L, Li J, et al. Efects of normalization management on prognosis in elderly patients with coronary artery disease. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2012;12(5):520–3.

Nieuwkerk PT, Nierman MC, Vissers MN, Locadia M, Greggers-Peusch P, Knape LPM, et al. Intervention to improve adherence to lipid-lowering medication and lipid-levels in patients with an increased cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(5):666–72.

Kardas P. An education-behavioural intervention improves adherence to statins. Cent Eur J Med. 2013;8(5):580–5.

Ali F, Laurin MY, Lariviere C, Tremblay D, Cloutier D. The effect of pharmacist intervention and patient education on lipid-lowering medication compliance and plasma cholesterol levels. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;10(3):101–6.

Guthrie RM. The effects of postal and telephone reminders on compliance with pravastatin therapy in a national registry: results of the first myocardial infarction risk reduction program. Clin Ther. 2001;23(6):970–80.

Stuurman-Bieze AGG, Hiddink EG, van Boven JFM, Vegter S. Proactive pharmaceutical care interventions improve patients’ adherence to lipid-lowering medication. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(11):1448–56.

Brath H, Morak J, Kastenbauer T, Modre-Osprian R, Strohner-Kastenbauer H, Schwarz M, et al. Mobile health (mHealth) based medication adherence measurement—a pilot trial using electronic blisters in diabetes patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(S1):47–55.

Lee SSC, Cheung PYP, Chow MSS. Benefits of individualized counseling by the pharmacist on the treatment outcomes of hyperlipidemia in Hong Kong. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44(6):632–9.

Eussen SRBM, Van Der Elst ME, Klungel OH, Rompelberg CJM, Garssen J, Oosterveld MH, et al. A pharmaceutical care program to improve adherence to statin therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(12):1905–13.

Vrijens B, Belmans A, Matthys K, de Klerk E, Lesaffre E. Effect of intervention through a pharmaceutical care program on patient adherence with prescribed once-daily atorvastatin. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(2):115–21.

Casebeer L, Huber C, Bennett N, Shillman R, Abdolrasulnia M, Salinas GD, et al. Improving the physician-patient cardiovascular risk dialogue to improve statin adherence. BMC Fam Pract. 2009. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-10-48.

Hedegaard U, Kjeldsen LJ, Pottegard A, Bak S, Hallas J. Multifaceted intervention including motivational interviewing to support medication adherence after stroke/transient ischemic attack: a randomized trial. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2014;4(3):221–34.

Ma Y, Ockene IS, Rosal MC, Merriam PA, Ockene JK, Gandhi PJ. Randomized trial of a pharmacist-delivered intervention for improving lipid-lowering medication adherence among patients with coronary heart disease. Cholesterol. 2010. doi:10.1155/2010/383281.

Calvert SB, Kramer JM, Anstrom KJ, Kaltenbach LA, Stafford JA, Allen Lapointe NM. Patient-focused intervention to improve long-term adherence to evidence-based medications: a randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2012;163(4):657–65.

Stacy JN, Schwartz SM, Ershoff D, Shreve MS. Incorporating tailored interactive patient solutions using interactive voice response technology to improve statin adherence: results of a randomized clinical trial in a managed care setting. Popul Health Manag. 2009;12(5):241–54.

Ho PM, Lambert-Kerzner A, Carey EP, Fahdi IE, Bryson CL, Dee Melnyk S, et al. Multifaceted intervention to improve medication adherence and secondary prevention measures after acute coronary syndrome hospital discharge: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):186–93.

Goswami NJ, DeKoven M, Kuznik A, Mardekian J, Krukas MR, Liu LZ, et al. Impact of an integrated intervention program on atorvastatin adherence: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:647–55.

Holdford DA, Inocencio TJ. Adherence and persistence associated with an appointment-based medication synchronization program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2013;53(6):576–83.

Evans CD, Eurich DT, Taylor JG, Blackburn DF. The collaborative cardiovascular risk reduction in primary care (CCARP) study. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(8):766–75.

American Pharmacists Association Foundation. Pharmacy’s Appointment Based Model: a prescription synchronization program that improves adherence. White Paper. 2013. http://www.aphafoundation.org/sites/default/files/ckeditor/files/ABMWhitePaper-FINAL-20130923(3).pdf. Accessed 18 Aug 2016.

Hamine S, Gerth-Guyette E, Faulx D, Green BB, Ginsburg AS. Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015. doi:10.2196/jmir.3951.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by AstraZeneca Gothenburg, Mölndal, Sweden.

Conflict of interest

Magnus Jörntén-Karlsson, Staffan Berg and Matti Ahlqvist are employees of AstraZeneca Gothenburg, Mölndal, Sweden, which manufactures rosuvastatin. Stéphane Pintat and Michael Molloy-Bland are employees of Oxford PharmaGenesis Ltd, which receives funding from AstraZeneca.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jörntén-Karlsson, M., Pintat, S., Molloy-Bland, M. et al. Patient-Centered Interventions to Improve Adherence to Statins: A Narrative Synthesis of Systematically Identified Studies. Drugs 76, 1447–1465 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-016-0640-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-016-0640-x