Abstract

This article reflects on the 2010 pharmacovigilance legislation of the European Union (EU). Its legislative aim of better patient and public health protection through new responsibilities for pharmaceutical companies and regulatory bodies is considered to have been achieved and is well supported by the good pharmacovigilance practices ‘EU-GVP’. For future progress, we set out a vision for high-quality pharmacovigilance in a world of ongoing medical, technological and social changes. To deliver this vision, four principles are proposed to guide actions for further progressing the EU pharmacovigilance system: synergistic interactions with healthcare systems; trustworthy evidence for regulatory decisions; adaptive process efficiency; and readiness for emergency situations (the ‘STAR principles’). Like a compass, these principles should guide actions for building capacity, technology and methods; improving regulatory processes; and expanding policies, frameworks and research agendas. Fit for the future, the EU system should achieve further improved outputs in terms of safe, effective and trusted use of medicines and positive health outcomes within patient-centred healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Four principles are suggested to further progress pharmacovigilance in the European Union (EU) and achieve better outputs in terms of safe, effective and trusted use of medicines and positive health outcomes within patient-centred healthcare |

These principles should guide actions for system improvements through addressing challenges and using opportunities that arise from the ongoing medical, technological and social changes our world is facing |

The suggestions are a result of an in-depth review of data and of insights into the regulatory pharmacovigilance system of the EU, 10 years after its current legal basis became applicable in 2012 |

1 Introduction and Objective

The year 2022 marked the 10th anniversary of the coming into application of legislation that profoundly changed and strengthened pharmacovigilance in the European Union (EU) [1, 2]. Since then, we have observed multiple drivers for change of a global and interdependent nature, which have been accelerated during the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and now require adapted medicines regulatory strategies. In particular, these drivers concern the following.

-

Health and healthcare, including:

changing patterns in burden of disease and health challenges, new diagnostic methods, innovative platforms for medicines, personalised medicines, increasing patient-centred, home-based and virtual delivery of healthcare.

-

Data and media technology, including:

ongoing digitalisation of daily life and healthcare with real-world data collection, new methods for data analytics and evidence generation, artificial intelligence, changes in news and social media platforms, information-seeking and interactive behaviours, misinformation and disinformation threats.

-

Societal developments, including:

increasing self-organisation of people in virtual networks, varying levels of trust in governments and science, increasing expectations and demands of people for participation in health policy and decision making and evidence generation with patient-reported outcome and patient experience data.

-

Economic and environmental issues, including:

existing global economic and social inequalities, geopolitical challenges, climate change, growing interdependence across areas and regions, which also impact on supply of medicines and access to healthcare and medicines.

-

Public health emergencies, including:

emergencies arising from the above changes or from humanitarian or political crises, specific issues such as antimicrobial resistance, infectious diseases and substance use disorders [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

The 10-year anniversary of the operation of the 2010 legislation stimulated us to review and reflect on its implementation and impact, with the objective to provide, from an EU regulators’ viewpoint, a vision and principles to guide actions for further progressing high-quality pharmacovigilance in our changing world.

We want to share the reflections and guiding principles with all stakeholders of EU pharmacovigilance and consider that these may also be of global interest, given that the EU system has become a model for many jurisdictions around the world.

2 The 2010 European Union (EU) Pharmacovigilance Legislation

The 2010 legislation changed pharmacovigilance in the EU profoundly. Motivated by estimates at the time that about 5% of all hospital admissions and almost 200,000 deaths yearly in the EU were due to an adverse reaction to a medicine, the European Commission set as its legislative aim to strengthen and rationalise EU pharmacovigilance at regulatory and industry level [14]. As medicines use constitutes a high proportion of therapeutic interventions, pharmacovigilance and its risk management are essential for the protection of patient and public health. Pharmacovigilance spans from the pre- to post-authorisation phase of medicines and hence overcomes the limitations of the safety database established from pre-authorisation clinical trials by collecting and assessing data from diverse patient populations in everyday healthcare.

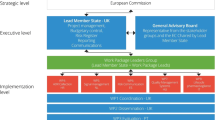

The EU medicines regulatory networks comprises the competent authorities (regulatory bodies) of the EU Member States, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the European Commission. Member States have been operating national pharmacovigilance systems since the 1960s, with the first EU Pharmaceutical Directive of 1965 as a common framework with requirements for quality, safety and efficacy for granting and maintaining marketing authorisations [15, 16]. In 1995, the EU regulatory pharmacovigilance system was established under the coordination of the then new EMA [17, 18]. Over the following years, adjustments to the legislation included a risk management approach to more proactively identify and minimise risks with medicines [19,20,21,22].

In 2004, the European Commission initiated a study into the EU pharmacovigilance system [23], conducted public consultations and an impact assessment, and considered recommendations from the ‘EU Risk Management Strategy’ (ERMS; a leadership group of the EU regulatory pharmacovigilance system) [24] and from patient representatives at EMA [25]. At the time, a particular need was to create a system that would also function robustly and efficiently after the EU enlargements in 2004, 2007 and 2013, which almost doubled the number of Member States (now 27). Prepared with this comprehensive multistakeholder input, the 2010 legislation was adopted. In 2012, an Implementing Regulation was added for technical and operational details [26]. The specific objectives of the 2010 legislation can be summarised as:

-

strengthen regulation of medicines in the post-authorisation phase;

-

strengthen the evidence-base for safety-related regulatory action;

-

strengthen quality and efficiency of pharmacovigilance;

-

strengthen transparency, communication, stakeholder engagement and international collaboration for pharmacovigilance purposes [14, 27].

An overview of how the EU regulatory pharmacovigilance system works under the 2010 legislation was published [28], as well as a review of the first 18 months of operation. This review demonstrated more systematic and proportionate risk management planning, greater coordination of real-time safety signal management, and faster risk assessment, decision making and updates to product information. It also looked forward to implementing all new legal provisions for efficiency gains and resource reallocation to increase the delivery of the legislative objectives [29]. From 2013 to 2016, the Member States’ regulatory bodies came together under their project ‘Strengthening Collaboration for Operating Pharmacovigilance in Europe (SCOPE) Joint Action’ to obtain an overview of how the national pharmacovigilance systems met their new requirements and to develop training, best practice tools and collaborative working practices for increasing capacity [30]. The EU regulatory network has closely monitored the implementation, impact and utility of the new legislation through 3-yearly assessments of the evolving system, with the latest assessment published in 2023 [31,32,33].

3 Reflections on the 2010 EU Pharmacovigilance Legal Provisions

Our reflections relate to the contributions of key legal provisions in fulfilling the specific legislative objectives. They are based on our observations and insights as some of the EU regulators closest to the design, implementation and monitoring of the legislation, based on data from the regular EU system assessments and the SCOPE Joint Action, as well as results from studies conducted by EMA and others over the first 10 years of operation. They also take into account the experiences with the safety surveillance for vaccines and therapeutics against COVID-19 (see Table 1 for this analysis).

Overall, we consider that the 2010 legislation achieved to strengthen and rationalise pharmacovigilance for better patient and public health protection through establishing new legal responsibilities for marketing authorisation holders (pharmaceutical companies), the regulatory bodies in Member States and EMA, notably:

-

Scientific committee: The Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) was established as a new scientific committee at EMA, with a central role for regulating safety in the pre- and post-authorisation phases and taking regulatory actions that are legally binding across the EU for medicines authorised either by the European Commission centrally or by Member States nationally.

-

Regulatory tools: New or strengthened regulatory tools (including risk management plans, post-authorisation studies, direct patient reporting of suspected adverse reactions, signal management, single EU assessments of periodic safety update reports, and reviews of medicines through referral procedures) have facilitated an increasingly proactive and consistent approach to medicines safety, complemented by improvements in efficiency of database infrastructures, evidence generation, regulatory processes and actions, and communication.

-

Transparency: Transparency was increased with public PRAC membership lists, agendas, recommendations and minutes, and public access to reports of suspected adverse reactions collected in EudraVigilance.

-

Stakeholder engagement: Engagement of key stakeholders, such as patients, healthcare professionals and academic researchers, has been broadened and deepened through tools to facilitate reporting of suspected adverse reactions, stakeholder reviews of draft communication documents, and invitations to patient and healthcare professional representatives to expert meetings, public hearings resulting in instrumental input to regulatory decision making, and research projects.

-

Evaluation of regulatory actions: The PRAC Strategy on Measuring the Impact of Pharmacovigilance Activities [34] systematically evaluates patient health-relevant outcomes of major regulatory actions.

During the last 3 years, the COVID-19 pandemic was a major, prolonged stress test for the system, which continued to be fully operational and delivered high-quality and efficient safety surveillance and communication for COVID-19 vaccines and new or repurposed therapeutics, while pharmacovigilance activities for all other medicines continued without compromise of standards [35].

Recently, the European Commission published their legislative proposals for the revision of the entire EU pharmaceutical legislation [36]. These proposals maintain the pharmacovigilance system provisions of the 2010 legislation with only very minor changes. This is a strong indicator of success of the 2010 provisions, as the European Commission’s proposals are based on a profound review and extensive stakeholder feedback.

A key enabler of the successful implementation and maintenance of pharmacovigilance systems of regulatory bodies and pharmaceutical companies in accordance with the 2010 legislation has been the ‘Good Pharmacovigilance Practices’ (EU-GVP) [37] (see Fig. 1), issued in 2012 to replace previous EU guidance. Fundamentally, EU-GVP introduced a systems approach to safety governance and pharmacovigilance conduct, with quality management as an integral part. This means applying good practice principles to all its tasks for achieving defined quality objectives and continuously monitoring systems to complete an iterative learning and improvement cycle [38] (see Fig. 2). Given a new modular guidance structure, each pharmacovigilance process has its own EU-GVP module (12 in total) with two main sections—one detailing the regulatory scientific process and applicable international standards, and one further describing the roles and responsibilities of pharmaceutical companies and regulatory bodies in the EU. The international standards are mainly those established through the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) [39, 40]. Each module also contains process-specific quality management and transparency requirements, and outlines applicable options for stakeholder engagement. With supplementary guidance chapters for special product types (at present, biologics and vaccines) and patient populations (at present, pregnant or breastfeeding women and children), as well as a definitions annex, EU-GVP provides comprehensive guidance. The crucial role of public communication for pharmacovigilance is reflected in a dedicated process module and additionally in sections of the product type- or population-specific chapters to advise on tailoring of communication. Subject to wide stakeholder consultations before finalisation and updating, EU-GVP is a participatory policy that responds to emerging needs and supports progress in conducting pharmacovigilance activities. EU-GVP has also been recognised as a resource for jurisdictions outside the EU (e.g. [41,42,43,44,45,46,47]).

Overview of the guidelines on ‘Good Pharmacovigilance Practices’ issued by the European Medicines Agency and the Heads of Medicines Agencies in the European Union (EU-GVP) [37]

While considering the achievements of the 2010 legislation, we have also identified areas for further development of the EU regulatory pharmacovigilance system (see Fig. 3). How to address these areas by optimising the use of existing legal provisions is part of our vision described in the following section.

Achievements and areas of further development through implementation of the 2010 EU pharmacovigilance legislation. EU European Union, PRAC Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee, PASS post-authorisation safety studies, PSURs periodic safety update reports, PAES post-authorisation efficacy studies

4 Envisioning the Future and Guiding Principles for Pharmacovigilance in a Changing World

4.1 Ongoing Initiatives

In 2019, EMA published its predictions for the ongoing decade: smarter collection and management of individual case safety reports with digital technology and international standards; increased use of real-world data for monitoring the performance of medicines in healthcare in terms of both safety and effectiveness; and improved engagement of patients and healthcare professionals that translates into positive patient health outcomes [48]. Furthermore, in 2020, the EMA’s regulatory science strategy highlighted real-world evidence (RWE) and stakeholder engagement as strategic priorities for pharmacovigilance [49]. Since then, major initiatives have been supporting the realisation of these predictions, in particular:

-

The PRAC Signal Management Review Technical (SMART) Working Group fosters innovative methods for more sensitive and precise signal detection and management, including for special populations and risks with medicines’ abuse, misuse, overdose, medication errors and occupational exposure [50].

-

The Data Analysis and Real World Interrogation Network (DARWIN EU) promotes timely and reliable RWE from healthcare databases across Europe and establishes an infrastructure for post-authorisation studies investigating the use, safety or effectiveness of medicines, background incidences of medical events, data on diseases for contextualising benefit-risk considerations, effectiveness of risk minimisation measures (RMM), impact of regulatory actions or patient preferences in European populations [51,52,53]. For generating EU RWE through independent post-authorisation studies specifically for vaccines, EMA and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) have initiated the Vaccine Monitoring Platform (VMP) [54].

-

The PRAC Risk Minimisation Alliance (PRISMA) pilots enhanced stakeholder engagement by PRAC to obtain more and earlier input from patient and healthcare professional networks on the feasibility of implementation of RMM options, questions to be discussed in wider stakeholder events, and outreach strategies for the implementation of RMM in healthcare by collaborating with key stakeholders.

4.2 Vision for the Future EU Regulatory Pharmacovigilance System

Building on these initiatives, we envision to address the areas for further development (see Fig. 3) and progress pharmacovigilance that is fit for the future in a world of medical, technological and social changes (see Sect. 1) with the following 10 elements:

-

1.

In the interest of all patient population groups and health equity, the EU regulatory pharmacovigilance system should streamline timely implementation of consistent safety-related actions for all medicines across Member States, independently from their route of marketing authorisation, and with implementation adapted to national healthcare systems.

-

2.

The contextual understanding of diseases, exposure to medicines, healthcare systems and the performance of medicines in terms of safety, risk minimisation as well as effectiveness in everyday healthcare in the EU should be deepened for more comprehensive benefit-risk assessments and important updates to the product information.

-

3.

Multiple data sources and multidisciplinary methods should be used and improved for real-time monitoring and assessment of risks, RMM (including their enablers and barriers to achieve intended outcomes) and effectiveness of medicines in consistent formats, based on study feasibility assessments, and in a complementary manner with cross-validation of findings.

-

4.

Targeted real-world data studies commissioned or conducted by regulators should supplement the important evidence base legally required from pharmaceutical companies, which should likewise be extended and improved.

-

5.

Advances in technology, including artificial intelligence, should be leveraged to deal with large volumes of data and enable efficient assessment.

-

6.

Proactive input from and research with patient and healthcare professional communities to support decisions and design of RMM should be sought within frameworks for their impartial contributions, and focus on risk minimisation behaviours and how these can be effectively integrated in local healthcare processes.

-

7.

Communication on risks and RMM should be contextualised in ways that support patients and healthcare professionals in making individual therapeutic choices and using medicines appropriately.

-

8.

Regulators should outreach to patient and healthcare professional communities and public health bodies to foster the appropriate use of medicines and build societal trust in medicines regulation and safety surveillance.

-

9.

All pharmacovigilance activities, such as spontaneous reporting of suspected adverse reactions, post-authorisation safety studies, and RMM development and implementation, should be integrated in patient-centred healthcare, and hence require strong healthcare system engagement.

-

10.

The EU regulatory pharmacovigilance system should be prepared to respond efficiently to different emergency situations.

4.3 The STAR Compass to Guide Actions to Further Progress Pharmacovigilance

To realise this vision, actions for progressing the EU regulatory pharmacovigilance system within the quality cycle may:

-

build further capacity, technology and methods;

-

drive improvements of existing regulatory processes; and

-

expand policies, frameworks and research agendas

and should be guided by the following four principles:

-

Synergistic interactions with healthcare systems;

-

Trustworthy evidence for regulatory decisions;

-

Adaptive process efficiency;

-

Readiness for emergency situations.

By their first letters, these guiding principles can be remembered by the acronym ‘STAR’. Like a compass, they are meant to orient improvement actions towards increasing the output of pharmacovigilance activities in terms of safe, effective and trusted use of medicines and positive health outcomes within patient-centred healthcare (see Fig. 4).

Actions for progress in accordance with these principles should not only address the ongoing changes but make use of the opportunities arising from the changing world. The STAR principles therefore top up the established pharmacovigilance quality principles [38] and add the following foci:

-

Synergistic interactions with healthcare systems: While medicines regulatory bodies regulate medicinal products but not healthcare delivery, regulatory engagement with stakeholders has evolved over the last decades, with a focus now not only on interacting but on benefiting from the opportunities of increasingly networked societies and digitally linked systems, and on creating synergies between activities led by different stakeholders. We consider that synergistic interactions, which respect the responsibilities of each stakeholder party, may support stakeholders in converging on pharmacovigilance objectives and engage healthcare leaders more in the safe use of medicines within patient-centred care.

-

Trustworthy evidence for regulatory decisions: Medicines regulatory bodies have long been legally required to assess all available evidence and therefore established standards and guidance for the robustness of data and increasingly multidisciplinary analytical methods. However, the additional focus now is that stakeholders and the public overall trust the evidence as robust and unbiased and can appreciate the appropriateness of regulatory decisions even when there are limitations in the available evidence. The contextual understanding of diseases, healthcare systems and medicine use and its outcomes is meant to increase the evidence base for regulatory decisions and to provide common ground for stakeholder engagement, where regulators adopt increased knowledge of the clinical situations patients and healthcare professionals are dealing with.

-

Adaptive process efficiency: Strengthening efficiency has been achieved with the 2010 legislation; however, the focus now is to foster the capacity of pharmacovigilance systems to adapt efficiency swiftly and smoothly to the challenges and opportunities of the medical, technological and social changes in the world.

-

Readiness for emergency situations: While pandemic preparedness as well as business continuity planning have been established at EMA for decades, the focus now is on being ready both through proactivity as well as responsiveness to imminent or developing, foreseen or unforeseen emergencies of a wider range, arising from the ongoing changes or crises.

5 Conclusions

We consider that the 2010 legislation achieved its aim to strengthen and rationalise pharmacovigilance in the EU for better patient and public health protection. A key enabler of its successful implementation has been the guidance for pharmaceutical companies and regulatory bodies in EU-GVP, introducing a systems approach to safety governance and pharmacovigilance conduct with quality management. The EU regulatory system demonstrated strength, efficiency and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic, and delivered high-quality safety surveillance for COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics, as well as all other medicines.

We have also identified areas for further system development by optimising the use of existing legal provisions. To address these areas and progress high-quality pharmacovigilance in a world of medical, technological and social changes, we set out a vision and propose four principles, the STAR compass. These principles should guide actions to further develop the EU regulatory pharmacovigilance system by orienting it towards our vision of safe, effective and trusted use of medicines and positive health outcomes within patient-centred care.

This should lead to pharmacovigilance further evolving from its originally mainly reactive approach with reviewing spontaneously reported suspected adverse reactions (which remain a vital data source), through the increasingly proactive approach with conducting epidemiological studies (now based on digitalised ‘big data’), towards an interactive approach with stakeholder engagement and participatory tools and events.

The success of the 2010 legislation would not have been possible without the resource investment and commitment of all stakeholders, i.e. regulators, pharmaceutical industry, researchers, healthcare professionals and patients, in their respective area of responsibilities, and we are grateful for this. Further progress will require continued collaboration at EU and international level. Through sharing our reflections, vision and proposed guiding principles, we underline our continued commitment to serve patient and public health.

References

European Union. Directive 2010/84/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2010 amending, as regards pharmacovigilance, Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use (amended further by Directive 2012/26/EU).

European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1235/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2010 amending, as regards pharmacovigilance of medicinal products for human use, Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 laying down Community procedures for the authorisation and supervision of medicinal products for human and veterinary use and establishing a European Medicines Agency, and Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 on advanced therapy medicinal products.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Innovation in medicines. Amsterdam: EMA. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/innovation-medicines. Accessed 18 Oct 2023.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Regulatory science strategy. Amsterdam: EMA. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/how-we-work/regulatory-science-strategy. Accessed 18 Oct 2023.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Big data. Amsterdam: EMA. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/how-we-work/big-data. Accessed 19 Oct 2023.

European Commission (EC). European Health Data Space. Brussels: EC. https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/european-health-data-space_en. Accessed 18 Oct 2023.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety and Directorate-General for International Partnerships. EU global health strategy: better health for all in a changing world. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2022.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Trust in government. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/governance/trust-in-government/. Accessed 19 Oct 2023.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD dis/mis resource hub: joining forces to fight dis- and misinformation. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/stories/dis-misinformation-hub/. Accessed 19 Oct 2023.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Ready for the next crisis? Investing in health system resilience. Paris: OECD; 2023.

World Health Organization (WHO). The Global Health Observatory: explore a world of health data. Geneva: WHO. https://www.who.int/data/gho. Accessed 19 Oct 2023.

World Health Organization (WHO). Infodemic. Geneva: WHO. https://www.who.int/health-topics/infodemic#tab=tab_1. Accessed 19 Oct 2023.

World Economic Forum (WEF). Future focus. pathways for progress from the Network of Global Future Councils 2020–2022. Geneva: WEF; 2025. p. 2022.

European Commission (EC). Strengthening pharmacovigilance to reduce adverse effects of medicines [MEMO/08/782]. Brussels: EC; 2008.

European Union. Council Directive 65/65/EEC of 26 January 1965 on the approximation of provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action relating to proprietary medicinal products.

European Commission (EC). Legal framework governing medicinal products for human use in the EU. Brussels: EC. https://health.ec.europa.eu/medicinal-products/legal-framework-governing-medicinal-products-human-use-eu_en. Accessed 29 Mar 2023.

European Union. Council Directive 93/39/EEC of 14 June 1993 amending Directives 65/65/EEC, 75/318/EEC and 75/319/EEC in respect of medicinal products.

European Union. Council Regulation (EEC) No 2309/93 of 22 July 1993 laying down Community procedures for the authorization and supervision of medicinal products for human and veterinary use and establishing a European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products.

European Union. Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use, as amended.

European Union. Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004 laying down Community procedures for the authorisation and supervision of medicinal products for human and veterinary use and establishing a European Medicines Agency, as amended.

Bahri P, Arlett P. Regulatory pharmacovigilance in the EU. In: Andrews EB, Moore N, editors. Mann’s pharmacovigilance, Chapter 12. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell; 2014.

Tsintis P, La Mache E. CIOMS and ICH initiatives in pharmacovigilance and risk management: overview and implications. Drug Saf. 2004;27:509–17.

European Commission (EC). Commission public consultation: an assessment of the community system of pharmacovigilance (including the final report “Assessment of the European Community system of pharmacovigilance” submitted by the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research in collaboration with the Coordination Centre for Clinical Studies at the University Hospital of Tübingen to the EC under service contract No: FIF.20040739). Brussels: EC; 2006.

Heads of Medicines Agencies and European Medicines Agency (EMA). Action plan to further progress the European Risk Management Strategy. London: EMA; 2005.

EMEA/CHMP Working Group with Patient Organisations. Outcome of discussions: recommendations and proposals for action. London: European Medicines Agency; 2005.

European Union. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 520/2012 of 19 June 2012 on the performance of pharmacovigilance activities provided for in Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council.

Waller P. Getting to grips with the new European Union pharmacovigilance legislation. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:544–9.

Santoro A, Genov G, Spooner A, Raine J, Arlett P. Promoting and protecting public health: how the European Union pharmacovigilance system works. Drug Saf. 2017;40:855–69.

Arlett P, Portier G, de Lisa R, Blake K, Wathion N, Dogné J-M, Spooner, Raine J, Rasi G. Proactively managing the risk of marketed drugs: experience with the EMA Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014; 13: 395-397.

Radecka A, Loughlin L, Foy M, de Ferraz Guimaraes MV, Macolić Šarinić V, Di Giusti MD, Lesicar M, Straus S, Montero D, Pallos J, Ivanovic J, Raine J. Enhancing pharmacovigilance capabilities in the EU regulatory network: the SCOPE joint action. Drug Saf. 2018;41:1285–302.

European Commission (EC). Monitoring safety of medicines for patients: pharmacovigilance activities related to medicines for human use in the EU [COM (2016) 498] (period covered by the assessment: 2012–2014). Brussels: EC; 2017.

Heads of Medicines Agencies and European Medicines Agency (EMA). Report on pharmacovigilance tasks from EU Member States and the European Medicines Agency, 2015–2018. Amsterdam: EMA; 2019.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Report on pharmacovigilance tasks: from EU Member States and the European Medicines Agency, 2019–2022. Amsterdam: EMA; 2023.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). PRAC Strategy on Measuring the Impact of Pharmacovigilance Activities. London: EMA; 2017 and Rev 2. Amsterdam: EMA; 2022.

Wathion N. EMA’s response the COVID-19 pandemic: putting people’s health first. Amsterdam: European Medicines Agency (EMA); 2023.

European Commission (EC). Revision of the EU general pharmaceuticals legislation. Brussels: EC. https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12963-Revision-of-the-EU-general-pharmaceuticals-legislation_en. Accessed 23 Jun 2023.

European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Heads of Medicines Agencies. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices. London/Amsterdam: EMA; 2012 onwards.

European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Heads of Medicines Agencies. Module I of Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices: Pharmacovigilance systems and their quality systems. London: EMA; 2012.

International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). https://www.ich.org/. Accessed 16 Dec 2022.

Bahri P. Pharmacovigilance-related topics at the level of the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH). In: Andrews EB, Moore N, editors. Mann’s Pharmacovigilance, Chapter 5. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell; 2014.

Olsson S. Commonwealth summit in Ukraine. Uppsala Reports. 2014. p. 6–7.

National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC). NAFDAC good pharmacovigilance practice guidelines. Abuja: NAFDAC; 2016.

Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Risk management plans for medicines and biologicals: Australian requirements and recommendations. Woden: TGA; updated 29 Mar 2019. https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/resource/guidance/risk-management-plans-medicines-and-biologicals. Accessed 3 Apr 2023.

Garashi HY, Steinke DT, Schafheutle EI. A qualitative exploration of pharmacovigilance policy implementation in Jordan, Oman, and Kuwait using Matland’s ambiguity-conflict model. Glob Health. 2021;17:97.

Zhu J, Xu MJ. Implementing new GVP in China requires digitization and training. DIA Global Forum. Issue March 2022.

Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA). Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices. Riyadh: SFDA; 2023.

Khan MAA, Hamid S, Babar Z-U-D. Pharmacovigilance in high-income countries: current developments and a review of literature. Pharmacy. 2023;11(1):10.

Arlett P, Straus S, Rasi G. Pharmacovigilance 2030: invited commentary for the January 2020 “Futures” Edition of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;107:89–91.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). EMA Regulatory Science to 2025: strategic refection. Amsterdam: EMA; 2020.

Potts J, Genov G, Segec A, Raine J, Straus S, Arlett P. Improving the safety of medicines in the European Union: from signals to action. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;107:521–9.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Data Analysis and Real World Interrogation Network (DARWIN EU). Amsterdam: EMA; 2021 onwards. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/how-we-work/big-data/data-analysis-real-world-interrogation-network-darwin-eu. Accessed 28 Jul 2022.

Cave A, Kurz X, Arlett P. Real-world data for regulatory decision making: challenges and possible solutions for Europe. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106:36–9.

Arlett P, Kjær J, Broich K, Cooke E. Real-world evidence in EU medicines regulation: enabling use and establishing value. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022;111:21–3.

European Medicines Agency and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Vaccine Monitoring Platform. Stockholm: ECDC. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/about-ecdc/what-we-do/partners-and-networks/eu-institutions-and-agencies/vaccine-monitoring. Accessed 30 June 2023.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee: rules of procedure. London: EMA; 2012, and Rev 3. Amsterdam: EMA; 2021

Inspection générale des affaires sociales (IGAS). Enquête sur le MEDIATOR® (rapport definitif RM2011-001P). Paris: IGAS; 2011.

European Union. Directive 2012/26/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 amending Directive 2001/83/EC as regards pharmacovigilance.

International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline on post-approval safety data management: definitions and standards for expedited reporting (ICH-E2D). Geneva: ICH; 2003.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). PRAC good practice guide on recording, coding, reporting and assessment of medication errors. Amsterdam: EMA; 2015.

Durand J, Dogné JM, Cohet C, Browne K, Gordillo-Marañón M, Piccolo L, Zaccaria C, Genov G. Safety monitoring of COVID-19 vaccines: perspective from the European Medicines Agency. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023;113:1223–34.

Härmark L, Raine J, Leufkens H, Edwards IR, Moretti U, Macolic Sarinic V, Kant A. Patient-reported safety information: a renaissance of pharmacovigilance? Drug Saf. 2016;39:883–90.

Banovac M, Candore G, Slattery J, Houÿez F, Haerry D, Genov G, Arlett P. Patient reporting in the EU: analysis of EudraVigilance data. Drug Saf. 2017;40:629–45.

Adopo D, Daynes P, Benkebil M, Debs A, Jonville-Berra AP, Polard E, Micallef J, Maison P. Patient involvement in pharmacovigilance: determinants and evolution of reporting from 2011 to 2020 in France. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;79:229–36.

Varallo FR, Guimaraes SOP, Abjaude SAR, Mastroianni PC. Causes for the underreporting of adverse drug events by health professionals: a systematic review. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2014;48:739–47.

Al Dweik R, Dawn S, Kohen D, Yaya S. Factors affecting patient reporting of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:875–83.

O’Callaghan J, Griffin BT, Morris JM, Bermingham M. Knowledge of adverse drug reaction reporting and the pharmacovigilance of biological medicines: a survey of healthcare professionals in Ireland. Bio Drugs. 2018;32:267–80.

Patrignani A, Palmieri G, Ciampani N, Moretti V, Mariani A, Racca L. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions, a problem that also involves medicines subject to additional monitoring. Preliminary data from a single-center experience on novel oral anticoagulants. G Ital Cardiol. 2018;19:54–61.

Januskiene J, Segec A, Slattery J, Genov G, Plueschke K, Arlett P, Kurz X. What are the patients’ and health care professionals’ understanding and behaviors towards adverse drug reaction reporting and additional monitoring? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30:334–41.

Amiri A, Okai J, Bahri P, Macolić ŠV. The fundamental value of exposure data for pharmacovigilance: review of different aggregation levels of exposure data in pharmaceutical companies’ period Safety update reports [abstract of poster at 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Pharmacovigilance (ISoP) in November 2021]. Drug Saf. 2021;44(1402):P002.

Grupstra RJ, Goedecke T, Scheffers J, Strassmann V, Gardarsdottir H. Review of studies evaluating effectiveness of risk minimisation measures assessed by the European Medicines Agency between 2016 and 2021. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023;114:1285–92.

Okai J, Bahri P, Macolić ŠV. Reporting quality of evaluations of additional risk minimisation measure by MAH: an assessment of studies submitted in the European Union [abstract of poster for 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Pharmacovigilance (ISoP) in November 2021]. Drug Saf. 2021;44(1402):P003.

International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO 9000 Family: Quality management. https://www.iso.org/iso-9001-quality-management.html. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Coordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures—Human (CMDh). Annex 2: HaRP (Harmonisation of RMP Project)—methodology of harmonising RMPs. Amsterdam: CMDh; 2019, 2021 (rev 1).

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Reflection paper on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the medicinal product lifecycle [draft]. Amsterdam: EMA; 2023.

Hines PA, Herold R, Pinheiro L, Frias Z, Arlett P. Artificial intelligence in European medicines regulation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22:81–2.

Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI). Pharmacoepidemiological research on outcomes of therapeutics by a European consortium (PROTECT). https://www.imi.europa.eu/projects-results/project-factsheets/protect. Accessed 25 Oct 2022.

Pacurariu A, van Haren A, Berggren A-L, Grundmark B, Zondag D, Harder H, Vestergaard Laursen M, Tregunno P, Rayon P, Owen R, Straus S. SCOPE work package 5 on signal management: best practice guide. Strengthening Collaboration for Operating Pharmacovigilance in Europe (SCOPE) Joint Action; June 2016.

World Health Organization (WHO). Guidance for clinical case management of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) following vaccination to prevent coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [interim guidance]. Geneva: WHO; 2021.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). COVID-19 vaccine safety update of 14 April 2021: Vaxzevria. Amsterdam: EMA; 2021.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). COVID-19 vaccine safety update of 14 April 2021: COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen. Amsterdam: EMA; 2021.

Candore G, Monzon S, Slattery J, Piccolo L, Postigo R, Xurz X, Strauss S, Arlett P. The impact of mandatory reporting of non-serious safety reports to EudraVigilance on the detection of adverse reactions. Drug Saf. 2022;45:83–95.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Measuring the impact of pharmacovigilance activities. Amsterdam: EMA. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/pharmacovigilance-overview#measuring-the-impact-of-pharmacovigilance-activities-(updated)-section. Accessed 28 Feb 2023.

Goedecke T, Morales D, Pacurariu A, Kurz X. Measuring the impact of medicines regulatory interventions: systematic review and methodological considerations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:419–33.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Public hearing on valproate: first experience and lessons learnt. London: EMA; 2017.

Bahri P, Morales DR, Inoubli A, Dogné JM, Straus SMJM. Proposals for engaging patients and healthcare professionals in risk minimisation from an analysis of stakeholder input to the EU valproate assessment using the novel analysing stakeholder safety engagement tool (ASSET). Drug Saf. 2021;44:193–209.

Bahri P, Pariente A. Systematising pharmacovigilance engagement of patients, healthcare professionals and regulators: a practical decision guide derived from the International Risk Governance Framework for engagement events and discourse. Drug Saf. 2021;44:1193–208.

Brown P, Bahri P. ‘Engagement’ of patients and healthcare professionals in regulatory pharmacovigilance: establishing a conceptual and methodological framework. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;75:1181–92.

Bahri P. A multilayered research framework for humanities and epidemiology of medicinal product risk communication. In: Bahri P, editor. Communicating about risks and safe use of medicines: real life and applied research, Chapter 1. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2020.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). EudraVigilance: European database of suspected adverse drug reaction reports. https://www.adrreports.eu. Accessed 25 Oct 2022.

Bhasale AL, Sarpatwari A, De Bruin ML, Lexchin J, Lopert R, Bahri P, Mintzes BJ. Postmarket safety communication for protection of public health: a comparison of regulatory policy in Australia, Canada, the European Union, and the United States. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;109:1424–42.

Lofstedt R, Bouder F, Chakraborty S. Transparency and the Food and Drug Administration: quantitative study. J Health Commun. 2013;18:391–6.

Bahri P, Fogd J, Morales D, Kurz X, ADVANCE Consortium. Application of real-time global media monitoring and ‘derived questions’ for enhancing communication by regulatory bodies: the case of human papillomavirus vaccines. BMC Med. 2017;15:91.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Annex to Vaxzevria Art.5-3—visual risk contextualisation. Amsterdam: EMA; 2021.

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS). https://cioms.ch. Accessed 1 May 2024.

Dal Pan G, Arlett P. The US Food and Drug Administration-European Medicines Agency collaboration in pharmacovigilance: common objectives and common challenges. Drug Saf. 2015;38:13–5.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA). Amsterdam: EMA. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/partners-networks/international-activities/multilateral-coalitions-initiatives/international-coalition-medicines-regulatory-authorities-icmra. Accessed 2 Sep 2022.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). EMA to support establishment of the African Medicines Agency [news release]. Amsterdam: EMA; 2024. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-support-establishment-african-medicines-agency. Accessed 1 May 2024.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the memory of Noël Wathion (11 September 1956–12 August 2023), former EMA Deputy Director, in acknowledgement of his leadership in establishing and strengthening the EU pharmacovigilance system. Noël’s vision, dedication and humanity guided all of us in our public health mission. The views expressed in this article are the authors’ personal views and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflect the position of their employers, or of the EMA or one of EMA’s committees or working parties

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No specific funding was received for the conduct of this study.

Conflict of interest

Priya Bahri, Georgy Genov, Peter Arlett, Viola Macolić Šarinić, Evdokia Korakianiti, Alexis Nolte, Martin Huber, and Sabine M.J.M. Straus have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Ethics approval

This article did not require ethics approval as no research in humans or animals was conducted for the purpose of this article.

Consent to participate

This article did not require consent to participate as no research in humans was conducted for the purpose of this article.

Consent for publication

This article did not require consent to publication as no research in humans was conducted for the purpose of this article.

Availability of data and material (data transparency)

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analysed for the purpose of this article.

Code availability (software application or custom code)

Not applicable to this article.

Author contributions

This article was developed in three steps. The first step was an in-depth discussion between PB, GG, PA, EK and SS on their observations and insights. Based on this discussion, a discussion with AN, and data from the regular EU system assessments, the SCOPE Joint Action, and studies, PB prepared the analysis in Table 1, developed the guiding principles and provided a first draft of the manuscript for comments by GG, PA, EK, AN and SS. As a second step, the revised draft was critically reviewed and expanded by VMS and MH. As a third step, all authors independently provided their views on the priority elements for consolidating the vision of future pharmacovigilance. All authors reviewed the mature draft, which was finalised by PB, GG and PA for journal submission. The revised manuscript addressing the journal’s reviewers’ comments was reviewed by all authors. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bahri, P., Genov, G., Arlett, P. et al. The STAR Compass to Guide Future Pharmacovigilance Based on a 10-Year Review of the Strengthened EU System. Drug Saf (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-024-01451-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-024-01451-3